Submitted:

11 December 2023

Posted:

12 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

The present study

2. Materials and Methods

Participants

Measures

Procedure

Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary analysis

3.2. Multivariate Analysis of Variance

3.3. Hierarchical Regression Analyses

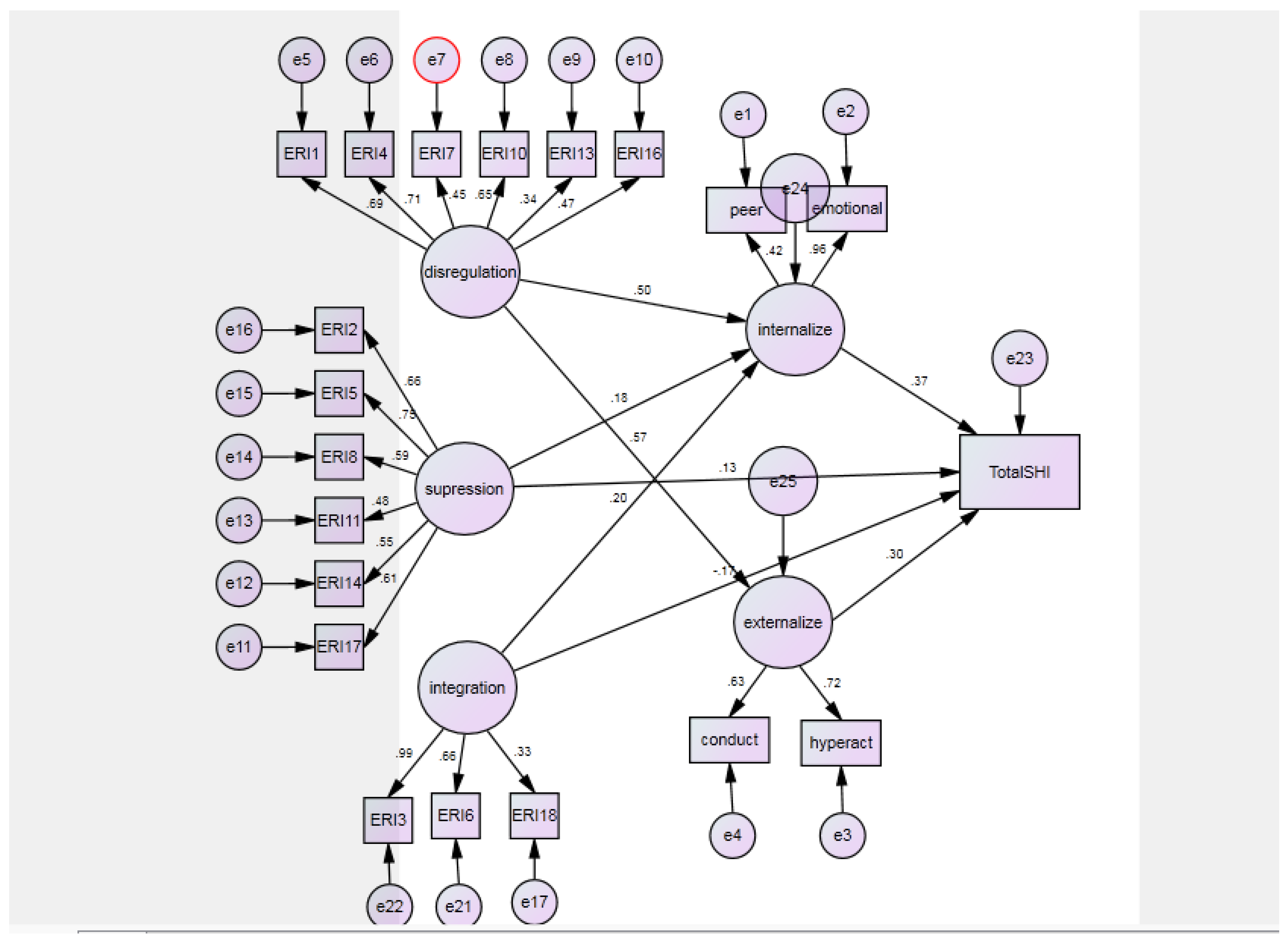

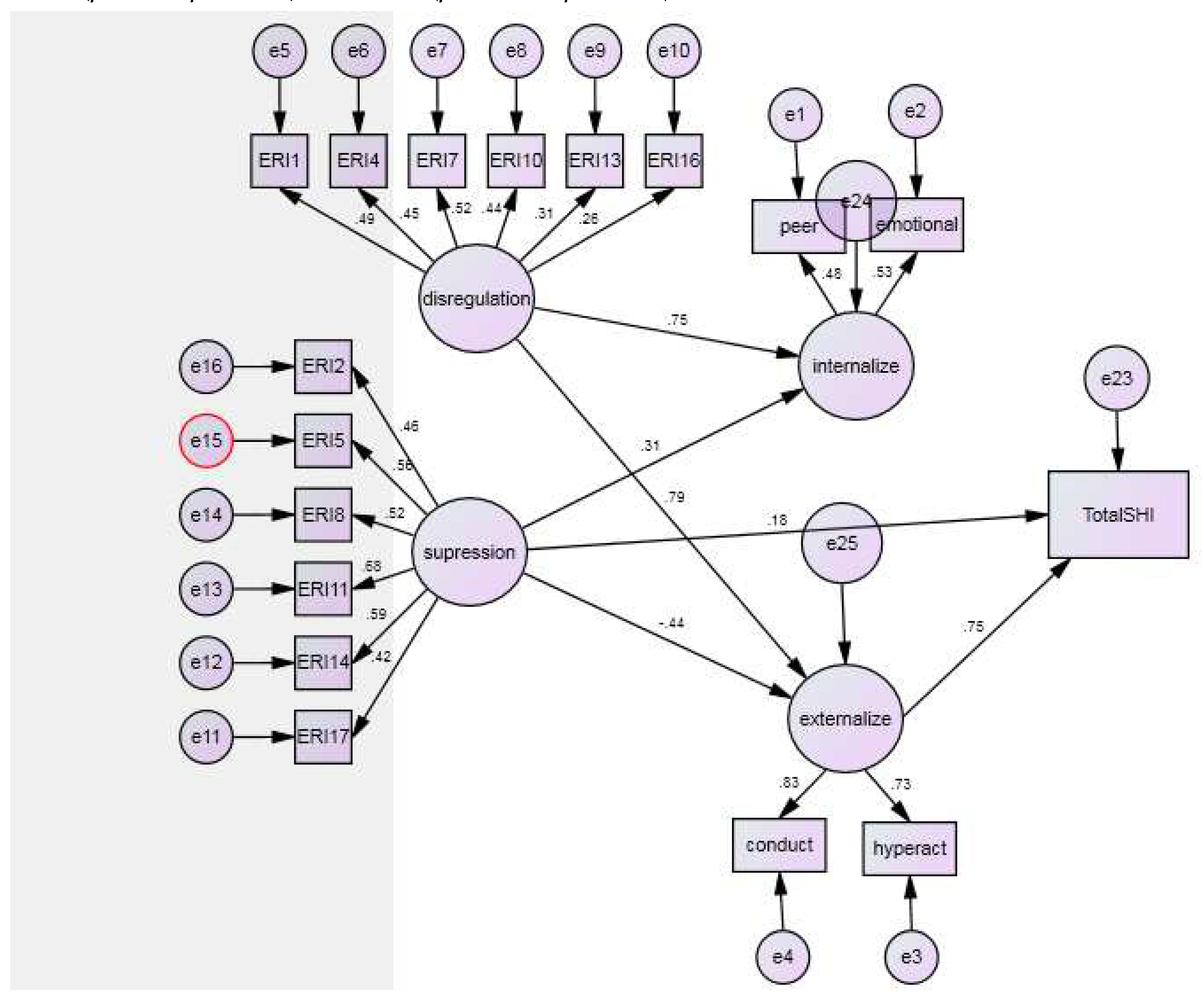

3.3. Mediation Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gross, J.J. Emotion Regulation: Current Status and Future Prospects. Psychological Inquiry 2015, 26, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRae, K.; Gross, J.J. Emotion Regulation. Emotion 2020, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, T.; Schulze, L.; Renneberg, B. The Role of Emotion Regulation in the Characterization, Development and Treatment of Psychopathology. Nature Reviews Psychology 2022, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compas, B.E.; Jaser, S.S.; Bettis, A.H.; Watson, K.H.; Gruhn, M.A.; Dunbar, J.P.; Williams, E.; Thigpen, J.C. Coping, Emotion Regulation, and Psychopathology in Childhood and Adolescence: A Meta-Analysis and Narrative Review. Psychological Bulletin 2017, 143, 939–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner, K.; Gross, J.J. Emotion Regulation and Psychopathology: A Conceptual Framework. In Emotion regulation and psychopathology: A transdiagnostic approach to etiology and treatment.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, US, 2010; pp. 13–37. [Google Scholar]

- DeSteno, D.; Gross, J.J.; Kubzansky, L. Affective Science and Health: The Importance of Emotion and Emotion Regulation. Health Psychology 2013, 32, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, S.E.; Betts, L.R.; Stiller, J.; Coates, J. The Role of Emotion Regulation for Coping with School-Based Peer-Victimisation in Late Childhood. Personality and Individual Differences 2017, 107, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, R.; Nguyen, N.; Gyorda, J.; Jacobson, N. Adolescent Emotion Regulation and Future Psychopathology: A Prospective Transdiagnostic Analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 2022, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, C.; Zolkoski, S. Preventing Stress Among Undergraduate Learners: The Importance of Emotional Intelligence, Resilience, and Emotion Regulation. Frontiers in Education 2020, 5, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanno, G.; Burton, C. Regulatory Flexibility: An Individual Differences Perspective on Coping and Emotion Regulation. Perspectives on Psychological Science 2013, 8, 591–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, G.; Benita, M.; Amrani, C.; Shahar, B.; Asoulin, H.; Moed, A.; Bibi, U.; Kanat-Maymon, Y. Integration of Negative Emotional Experience Versus Suppression: Addressing the Question of Adaptive Functioning.; Emotion: Washington, D.C., 2014; Volume 14. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.; Deci, E. Self-Regulation and the Problem of Human Autonomy: Does Psychology Need Choice, Self-Determination, and Will? Journal of personality 2006, 74, 1557–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, G.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Ryan, R. Integrative Emotion Regulation: Process and Development from a Self-Determination Theory Perspective. Development and Psychopathology 2019, 31, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvers, J. Adolescence as a Pivotal Period for Emotion Regulation Development For Consideration at Current Opinion in Psychology. Current Opinion in Psychology 2021, 44. [Google Scholar]

- Bailen, N.H.; Green, L.M.; Thompson, R.J. Understanding Emotion in Adolescents: A Review of Emotional Frequency, Intensity, Instability, and Clarity. Emotion Review 2019, 11, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciejewski, D.; Lier, P.; Branje, S.; Meeus, W. A 5-Year Longitudinal Study on Mood Variability Across Adolescence Using Daily Diaries. Child Development, Advance Online Publication. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Brenning, K.; Soenens, B.; Vansteenkiste, M.; De Clercq, B.; Antrop, I. Emotion regulation as a transdiagnostic risk factor for (non)clinical adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing psychopathology : investigating the intervening role of psychological need experiences. CHILD PSYCHIATRY & HUMAN DEVELOPMENT. 2022, 53, 124–136. [Google Scholar]

- Brenning, K.; Waterschoot, J.; Dieleman, L.; Morbée, S.; Vermote, B.; Soenens, B.; et al. The role of emotion regulation in mental health during the COVID-19 outbreak : a 10-wave longitudinal study. STRESS AND HEALTH. 2023, 39, 562–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharf, N.; Benita, M.; Benish-Weisman, M. Emotion Regulation Styles and Adolescent Adjustment Following a COVID-19 Lockdown. Stress and Health 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benita, M.; Benish-Weisman, M.; Matos, L.; Torres, C. Integrative and Suppressive Emotion Regulation Differentially Predict Well-Being through Basic Need Satisfaction and Frustration: A Test of Three Countries. Motivation and Emotion 2020, 44, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenning, K.; Soenens, B.; Van Petegem, S.; Vansteenkiste, M. Perceived Maternal Autonomy Support and Early Adolescent Emotion Regulation: A Longitudinal Study. Social Development 2015, 24, 561–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatandoost, S.; Baetens, I.; Van Den Meersschaut, J.; Van Heel, M.; Van Hove, L. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the incidence of non-suicidal self-injury; a comparison between Iran and Belgium. Clinical Medicine Insights: Psychiatry. 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Brausch, A.; Clapham, R.; Littlefield, A. Identifying Specific Emotion Regulation Deficits That Associate with Nonsuicidal Self-Injury and Suicide Ideation in Adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 2022, 51, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Z.; Pau, K.; Md Yusof, H.; Huang, X. The Effect of Emotion Regulation on Non-Suicidal Self-Injury Among Adolescents: The Mediating Roles of Sleep, Exercise, and Social Support. Psychology Research and Behavior Management 2022, 15, 1451–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, K.; Garisch, J.A.; Kingi, T.; Brocklesby, M.; O’Connell, A.; Langlands, R.L.; Russell, L.; Wilson, M.S. Reciprocal Risk: The Longitudinal Relationship between Emotion Regulation and Non-Suicidal Self-Injury in Adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 2019, 47, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Society for the Study of Self-Injury. What is self-injury? 2018. Available online: https://itriples.org/about-self-injury/what-is-self-injury.

- Baetens, I.; Greene, D.; Van Hove, L.; Van Leeuwen, K.; Wiersema, R.; Desoete, A.; et al. Predictors and consequences of non-suicidal self-injury in relation to life, peer, and school factors. JOURNAL OF ADOLESCENCE. 2021, 90, 100–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassels, M.; Wilkinson, P. Non-suicidal self-injury in adolescence. Paediatrics and Child Health. 2016, 26, 554–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, K.; Garisch, J.A.; Wilson, M.S. Nonsuicidal self-injury thoughts and behavioural characteristics: Associations with suicidal thoughts and behaviours among community adolescents. J Affect Disord. 2021, 282, 1247–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldao, A.; Gee, D.G.; De Los Reyes, A.; Seager, I. Emotion regulation as a transdiagnostic factor in the development of internalizing and externalizing psychopathology: Current and future directions. Development and Psychopathology. 2016, 28, 927–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cludius, B.; Mennin, D.; Ehring, T. Emotion Regulation as a Transdiagnostic Process. Emotion 2020, 20, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, P.M.; Hall, S.E.; Hajal, N.J.; Beauchaine, T.P.; Hinshaw, S.P. Emotion dysregulation as a vulnerability to psychopathology. Child and adolescent psychopathology. 2017, 346–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, R.Y.; Hardan, A.Y.; Phillips, J.M.; Frazier, T.W.; Uljarević, M. Brief Report: Emotion Regulation Influences on Internalizing and Externalizing Symptoms Across the Normative-Clinical Continuum. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavicchioli, M.; Stefanazzi, C.; Tobia, V.; Ogliari, A. The Role of Attachment Styles in Attention- Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Meta-Analytic Review from the Perspective of a Transactional Development Model The Role of Attachment Styles in Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Meta-Analytic Review from the Perspective of a Transactional Development Model. European Journal of Developmental Psychology 2022, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, R.; Arch, J.; Landy, L.; Hankin, B. The Longitudinal Effect of Emotion Regulation Strategies on Anxiety Levels in Children and Adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology 2016, 47, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baetens, I.; Claes, L.; Muehlenkamp, J.; Grietens, H.; Onghena, P. Differences in Psychological Symptoms and Self-Competencies in Non-Suicidal Self-Injurious Flemish Adolescents. Journal of Adolescence 2012, 35, 753–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriano, A.; Cella, S.; Cotrufo, P. Nonsuicidal Self-Injury: A Systematic Review. Frontiers in Psychology 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nock, M.; Prinstein, M. A Functional Approach to the Assessment of Self-Mutilative Behavior. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology 2004, 72, 885–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranzler, A.; Fehling, K.B.; Anestis, M.D.; Selby, E.A. Emotional dysregulation, internalizing symptoms, and self-injurious and suicidal behavior: Structural equation modeling analysis. Death Studies 2016, 40, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arens, E.A.; Balkir, N.; Barnow, S. Ethnic Variation in Emotion Regulation: Do Cultural Differences End Where Psychopathology Begins? Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 2013, 44, 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, D.; Yoo, S.H.; Nakagawa, S. ; Culture, Emotion Regulation, and Adjustment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 2008, 94, 925–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, T.; Zhang, D.; Wang, J.-L.; Mistry, R.; Ran, G.; Wang, X. Relation between Emotion Regulation and Mental Health: A Meta-Analysis Review. Psychological Reports 2014, 114, 341–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, M.L.; Lucas, R.E. Adults’ Desires for Children’s Emotions Across 48 Countries: Associations with Individual and National Characteristics. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 2004, 35, 525–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Empirical Models of Cultural Differences. In Contemporary issues in cross-cultural psychology; Swets & Zeitlinger Publishers: Lisse, Netherlands, 1991; pp. 4–20. [Google Scholar]

- Ghorbani, N.; Bing, M.N.; Watson, P.J.; Davison, H.K.; LeBreton, D.L. Individualist and Collectivist Values: Evidence of Compatibility in Iran and the United States. Personality and Individual Differences 2003, 35, 431–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifzadeh, V. Middle Eastern-rooted families. In Developing Cross-Cultural Competence, 3rd ed.; Lynch, E., Hanson, M., Eds.; Brookes: Baltimore, MD, 2004; pp. 373–410. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R. M.; Deci, E. L. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness.; Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, US 2017; pp xii, 756. [CrossRef]

- Allen, V.; Windsor, T. PSYCHO-SOCIAL MODERATORS OF THE COUPLING OF STRESS AND NEGATIVE AFFECT: A MICRO-LONGITUDINAL STUDY. Innovation in Aging 2017, 1 (suppl_1), 863–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, K.; Platt, J. Annual Research Review: Sex, Gender, and Internalizing Conditions among Adolescents in the 21st Century - Trends, Causes, Consequences. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aka, B.T. Cultural Dimensions of Emotion Regulation. Psikiyatride Guncel Yaklasimlar - Current Approaches in Psychiatry 2023, 15, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potthoff, S.; Garnefski, N.; Miklósi, M.; Ubbiali, A.; Domínguez-Sánchez, F.J.; Martins, E.C.; Witthöft, M.; Kraaij, V. Cognitive Emotion Regulation and Psychopathology across Cultures: A Comparison between Six European Countries. Personality and Individual Differences 2016, 98, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, N.H.; Kiefer, R.; Goncharenko, S.; et al. Emotion regulation and substance use: A meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend 2022, 230, 109131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, R.; Meltzer, H.; Bailey, V. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: a pilot study on the validity of the self-report version. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1998, 7, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, A.; Goodman, R. Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire as a Dimensional Measure of Child Mental Health. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 2009, 48, 400–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muris, P.; Meesters, C.; van den Berg, F. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ)--further evidence for its reliability and validity in a community sample of Dutch children and adolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2003, 12, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi, M.; Mohammadi, M.R.; Md, J.; Tehranidoost, M.; Shahrivar, Z.; Saadat, S. The Farsi Version of the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire Selfreport Form: The Normative Data and Scale Properties. iranian Journal of child neurology 2009, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, R. Psychometric Properties of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2001, 40, 1337–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, G.; Assor, A.; Niemiec, C.P.; Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. The Emotional and Academic Consequences of Parental Conditional Regard: Comparing Conditional Positive Regard, Conditional Negative Regard, and Autonomy Support as Parenting Practices. Developmental Psychology 2009, 45, 1119–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenning, K.; Soenens, B.; Braet, C.; Bosmans, G. Attachment and depressive symptoms in middle childhood and early adolescence: testing the validity of the emotion regulation model of attachment. PERSONAL RELATIONSHIPS 2012, 19, 445–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansone, R.A.; Wiederman, M.W.; Sansone, L.A. The Self-Harm Inventory (SHI): Development of a Scale for Identifying Self-Destructive Behaviors and Borderline Personality Disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychology 1998, 54, 973–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Routledge, 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesquita, B.; Boiger, M. Emotions in Context: A Sociodynamic Model of Emotions. Emotion Review 2014, 6, 298–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadkhah, A.; Shirinbayan, P. Emotion Regulation Characteristics Development in Iranian Primary School Pupils. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 2014, 12, 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Insights, H. Hofstede insights country comparison tool 2020.

- Butler, E.A.; Lee, T.L.; Gross, J.J. Emotion Regulation and Culture: Are the Social Consequences of Emotion Suppression Culture-Specific? Emotion 2007, 7, 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, J.A.; Levenson, R.W.; Ebling, R. Cultures of Moderation and Expression: Emotional Experience, Behavior, and Physiology in Chinese Americans and Mexican Americans. Emotion 2005, 5, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahmouresi, N.; Bender, C.; Schmitz, J.; Baleshzar, A.; Tuschen-Caffier, B. Similarities and Differences in Emotion Regulation and Psychopathology in Iranian and German School-Children: A Cross-Cultural Study. International journal of preventive medicine 2014, 5, 52–60. [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin, K.A.; Sheridan, M.A.; Tibu, F.; Fox, N.A.; Zeanah, C.H.; Nelson, C.A. Causal Effects of the Early Caregiving Environment on Development of Stress Response Systems in Children. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2015, 112, 5637–5642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clapham, R.; Brausch, A. Internalizing and Externalizing Symptoms Moderate the Relationship Between Emotion Dysregulation and Suicide Ideation in Adolescents. Child Psychiatry & Human Development 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLaughlin, K.A.; Hatzenbuehler, M.L.; Mennin, D.S.; Nolen-Hoeksema, S. Emotion dysregulation and adolescent psychopathology: a prospective study. Behav Res Ther 2011, 49, 544–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolff, J.C.; Thompson, E.; Thomas, S.A.; et al. Emotion dysregulation and non-suicidal self-injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Psychiatry 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.-L.; Chun, C.-C. Association between Emotion Dysregulation and Distinct Groups of Non-Suicidal Self-Injury in Taiwanese Female Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.; Bonnaire, C. Relationship Between Non-Suicidal Self-Injury and Emotion Dysregulation Among Male and Female Young Adults. Psychol Rep 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abela, J.R.; Brozina, K.; Haigh, E.P. An examination of the response styles theory of depression in third- and seventh-grade children: a short-term longitudinal study. J Abnorm Child Psychol 2002, 30, 515–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S.; Heath, N. A Study of the Frequency of Self-Mutilation in a Community Sample of Adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 2002, 31, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooley, J.M.; Franklin, J.C. Why Do People Hurt Themselves? A New Conceptual Model of Nonsuicidal Self-Injury. Clinical Psychological Science 2018, 6, 428–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholamrezaei, M.; De Stefano, J.; Heath, N.L. Nonsuicidal self-injury across cultures and ethnic and racial minorities: A review. Int J Psychol 2017, 52, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | M (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 1.INT | 7.52 (3.26) | 1 | |||||

| 2.EXT | 5.65 (3.83) | 0.06 | 1 | ||||

| 3.NSSI | 2.10 (2.09) | 0.16** | 0.54** | 1 | |||

| 4.DER | 2.77 (.75) | 0.29** | 0.43** | 0.38** | 1 | ||

| 5.SER | 3.21 (.84) | 0.32** | -0.37** | -0.18** | -0.07 | 1 | |

| 6.IER | 2.98 (.79) | -0.09 | 0.11 | 0.001 | 0.14* | -0.19** | 1 |

| Variables | M (SD) Belgium | M (SD) Iran | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 1.INT | 1 | 0.32** | 0.27** | 0.31** | 0.21* | -0.03 | ||

| 2.EXT | 0.22* | 1 | 0.57** | 0.48** | -0.26** | 0.11 | ||

| 3.NSSI | 0.39** | 0.33** | 1 | 0.42** | -0.13 | -0.03 | ||

| 4.DER | 0.39** | 0.38** | 0.32** | 1 | 0.04 | 0.13 | ||

| 5.SER | 0.15 | -0.03 | 0.19* | -0.04 | 1 | 0.05 | ||

| 6.IER | 0.02 | -0.14 | -0.2* | 0.09 | -0.19* | 1 |

| Variables | Iran (n = 117) | Belgium (n = 107) | F |

| M (SD) | M (SD) | ||

| DER | 2.68 (0.74) | 2.86 (0.76) | 3.215 |

| SER | 3.65 (0.71) | 2.72 (0.71) | 95.9** |

| IER | 2.79 (0.82) | 3.19 (0.69) | 15.04** |

| Internalizing | 8.55 (2.6) | 6.39 (3.55) | 27.03** |

| Externalizing | 3.81 (3.3) | 7.57 (3.53) | 67.5** |

| NSSI | ||||||

| β | SE | B | T | |||

| Model 1 | Age | -0.07 | 0.13 | -0.13 | -0.99 | |

| Gender | -0.02 | 0.26 | -0.09 | -0.36 | ||

| Country | -0.44 | 0.32 | -1.85 | -5.76** | ||

| Model 2 | Age | -0.04 | 0.12 | -.080 | -0.62 | |

| Gender | -0.02 | 0.24 | -1.13 | 0.46 | ||

| Country | -0.46 | 0.33 | -1.92 | -5.69** | ||

| DER | 0.35 | 0.16 | 0.97 | 5.96** | ||

| SER | 0.05 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.81 | ||

| IER | -0.15 | 0.16 | -0.41 | -2.59 | ||

| Internalizing and Externalizing problems | ||||||

| β | SE | B | T | |||

| Model 1 | Age | -0.07 | 0.37 | -0.33 | -0.89 | |

| Gender | -0.13 | 0.70 | -1.42 | -.2.01 | ||

| Country | -0.17 | 0.86 | -1.86 | -2.14 | ||

| Model 2 | Age | -0.06 | 0.33 | -0.28 | -0.84 | |

| Gender | -0.60 | 0.63 | -0.63 | -1.00 | ||

| Country | -0.14 | 0.87 | -1.49 | -1.71 | ||

| DER | 0.49 | 0.42 | 3.45 | 8.18** | ||

| SER | 0.00 | 0.43 | 0.01 | 0.04 | ||

| IER | -0.05 | 0.41 | -0.36 | -0.88 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).