Submitted:

11 December 2023

Posted:

12 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Modern burden

Discrepancies

Standards and Apophenic vs. Evidence-based Forensic Medicine

The impact of COVID-19

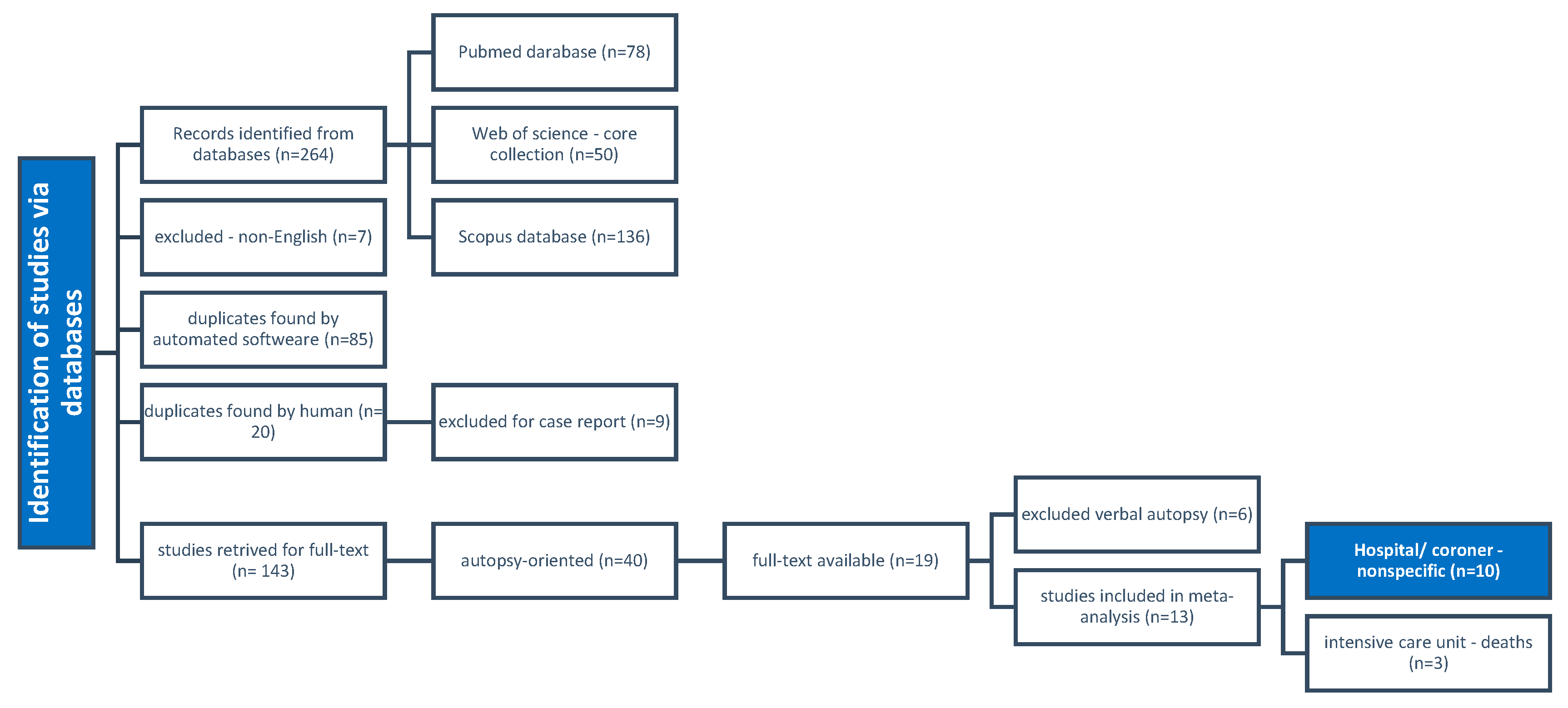

Literature search

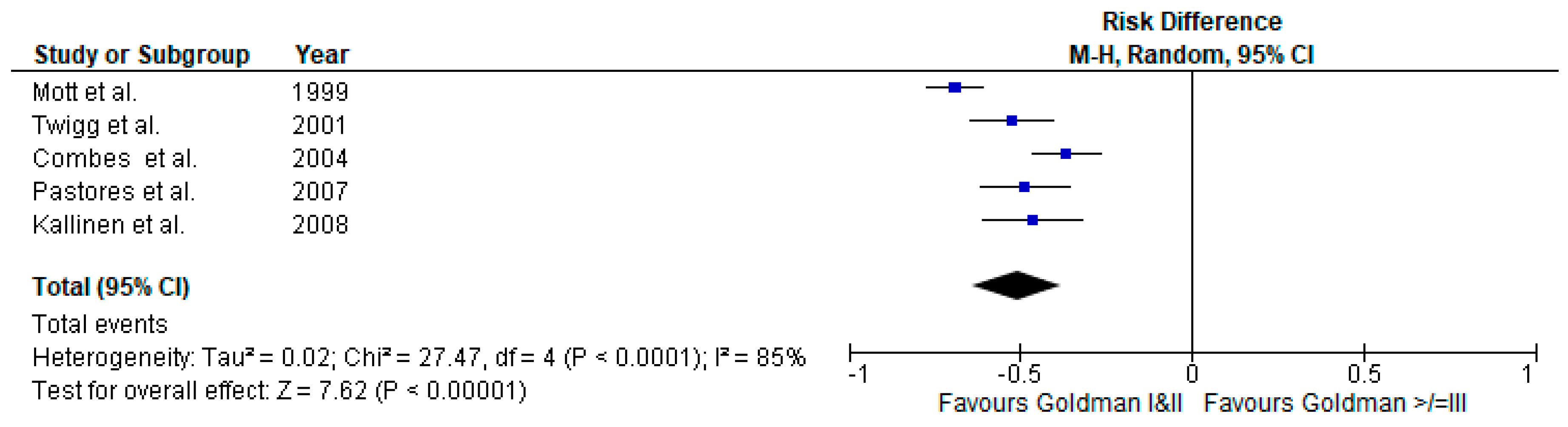

Scrutiny of intensive care unit as an exclusion criterion

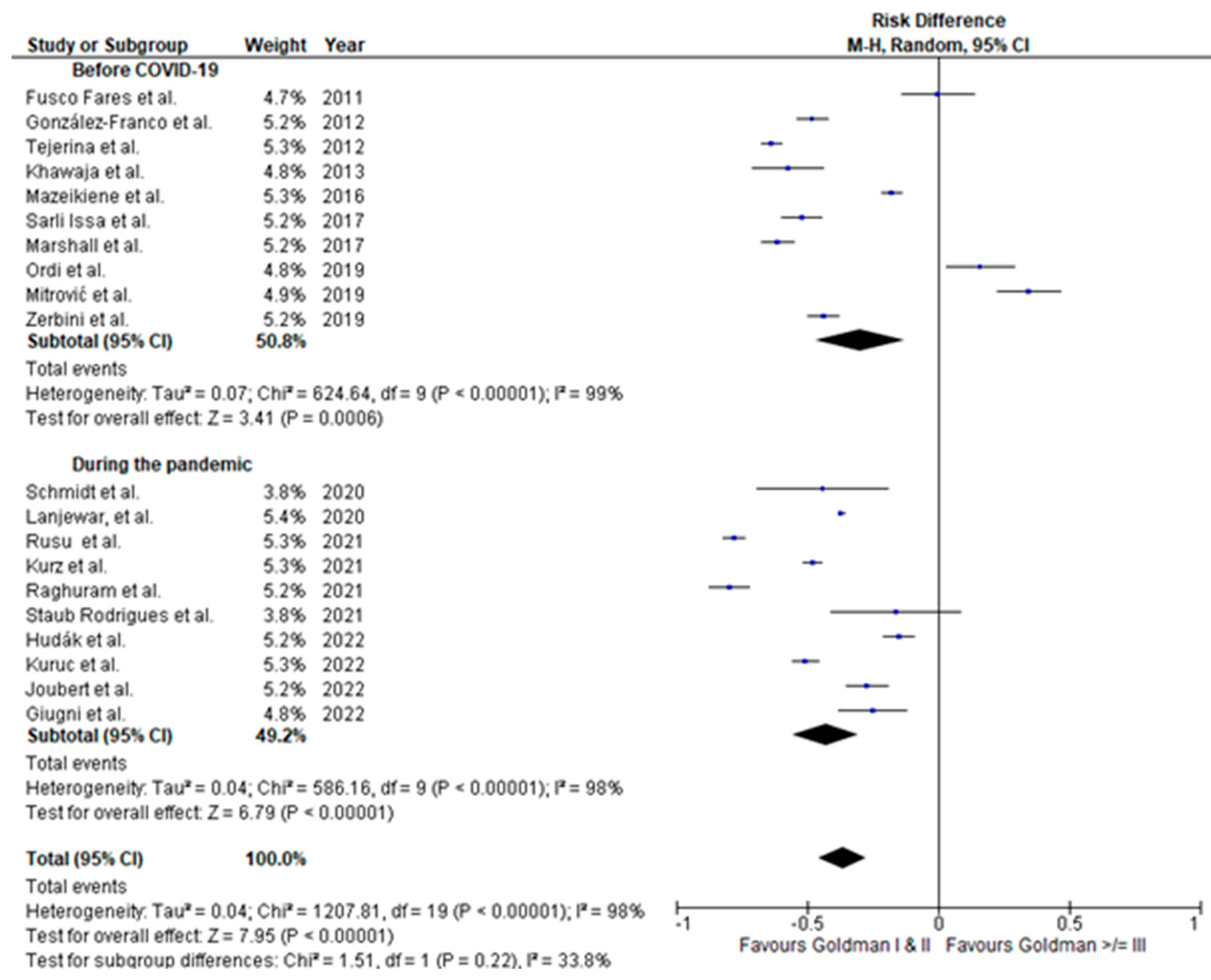

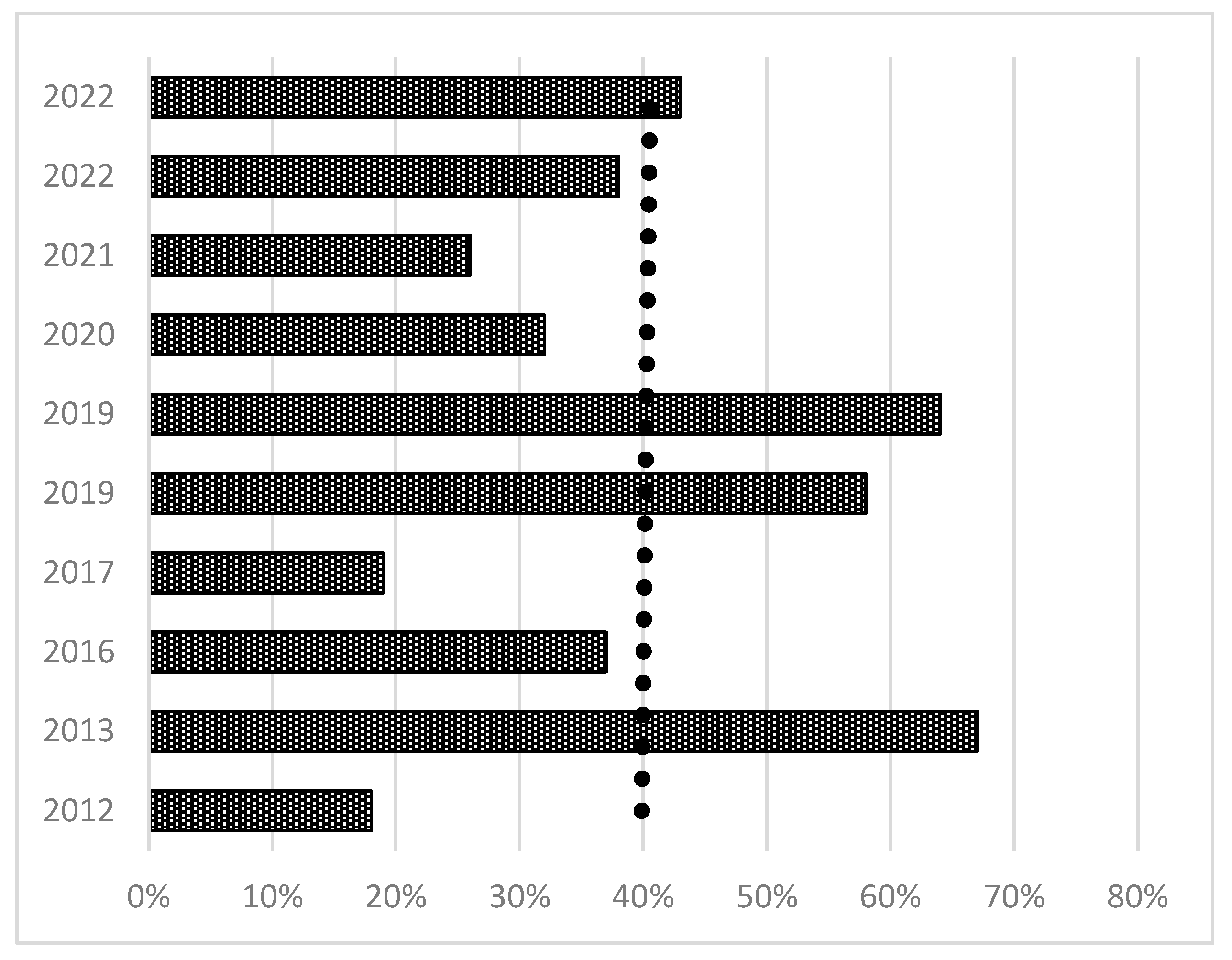

Meta-analysis of findings

Forensics in the Society 5.0

Documentation and Professional Approach

Postponed Burial and Retention of Organs

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- van den Tweel, J.G.; Taylor, C.R. The rise and fall of the autopsy. Virchows Arch 2013, 462, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Tweel, J.G.; Wittekind, C. The medical autopsy as quality assurance tool in clinical medicine: dreams and realities. Virchows Arch 2016, 468, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hundl, C.; Neuman, M.; Rairden, A.; Rearden, P.; Stout, P. Implementation of a Blind Quality Control Program in a Forensic Laboratory. J Forensic Sci 2020, 65, 815–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whiting, P.F.; Rutjes, A.W.; Westwood, M.E.; Mallett, S.; Deeks, J.J.; Reitsma, J.B.; Leeflang, M.M.; Sterne, J.A.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Group, Q.-. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med 2011, 155, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aludaat, C.; Sarsam, M.; Doguet, F.; Baste, J.M. Autopsy and clinical discrepancies in patients undergoing extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: a case series-a step towards understanding "Why"? J Thorac Dis 2019, 11, S1865–S1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zehr, K.J.; Liddicoat, J.R.; Salazar, J.D.; Gillinov, A.M.; Hruban, R.H.; Hutchins, G.M.; Cameron, D.E. The autopsy: still important in cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 1997, 64, 380–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurz, S.D.; Sido, V.; Herbst, H.; Ulm, B.; Salkic, E.; Ruschinski, T.M.; Buschmann, C.T.; Tsokos, M. Discrepancies between clinical diagnosis and hospital autopsy: A comparative retrospective analysis of 1,112 cases. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0255490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buja, L.M.; Barth, R.F.; Krueger, G.R.; Brodsky, S.V.; Hunter, R.L. The Importance of the Autopsy in Medicine: Perspectives of Pathology Colleagues. Acad Pathol 2019, 6, 2374289519834041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, K.K.; Shoemaker-Hunt, S.; Hoffman, L.; Richard, S.; Gall, E.; Schoyer, E.; Costar, D.; Gale, B.; Schiff, G.; Miller, K. Making healthcare safer III: a critical analysis of existing and emerging patient safety practices. 2020.

- Cooper, H.; Leigh, M.A.; Lucas, S.; Martin, I. The coroner's autopsy. The final say in establishing cause of death? Med Leg J 2007, 75, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, B.B.; Wong, J.J.; Hashim, J. A retrospective study of the accuracy between clinical and autopsy cause of death in the University of Malaya Medical Centre. Malays J Pathol 2004, 26, 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, H.; Lucas, S.B. The value of autopsy, believe it or not. Lancet 2007, 370, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, H.S.; Milikowski, C. Comparison of Clinical Diagnoses and Autopsy Findings: Six-Year Retrospective Study. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2017, 141, 1262–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonderegger-Iseli, K.; Burger, S.; Muntwyler, J.; Salomon, F. Diagnostic errors in three medical eras: a necropsy study. Lancet 2000, 355, 2027–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tejerina, E.; Esteban, A.; Fernandez-Segoviano, P.; Maria Rodriguez-Barbero, J.; Gordo, F.; Frutos-Vivar, F.; Aramburu, J.; Algaba, A.; Gonzalo Salcedo Garcia, O.; Lorente, J.A. Clinical diagnoses and autopsy findings: discrepancies in critically ill patients*. Crit Care Med 2012, 40, 842–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khawaja, O.; Khalil, M.; Zmeili, O.; Soubani, A.O. Major discrepancies between clinical and postmortem diagnoses in critically ill cancer patients: Is autopsy still useful? Avicenna J Med 2013, 3, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitrovic, D.; Savic, I.; Jankovic, R. Discrepancies between clinical and autopsy diagnosis of cause of death among psychiatric patients who died due to natural causes. A retrospective autopsy study. Vojnosanitetski Pregled 2019, 76, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanjewar, D.N.; Sheth, N.S.; Lanjewar, S.D.; Wagholikar, U.L. Analysis of Causes of Death as Determined at Autopsy in a Single Institute, The Grant Medical College and Sir J. J. Hospital, Mumbai, India, Between 1884 and 1966: A Retrospective Analysis of 13 024 Autopsies in Adults. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2020, 144, 644–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giugni, F.R.; Salvadori, F.A.; Smeili, L.A.A.; Marcilio, I.; Perondi, B.; Mauad, T.; de Paiva, E.F.; Duarte-Neto, A.N. Discrepancies Between Clinical and Autopsy Diagnoses in Rapid Response Team-Assisted Patients: What Are We Missing? J Patient Saf 2022, 18, 653–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudak, L.; Nagy, A.C.; Molnar, S.; Mehes, G.; Nagy, K.E.; Olah, L.; Csiba, L. Discrepancies between clinical and autopsy findings in patients who had an acute stroke. Stroke Vasc Neurol 2022, 7, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ordi, J.; Castillo, P.; Garcia-Basteiro, A.L.; Moraleda, C.; Fernandes, F.; Quintó, L.; Hurtado, J.C.; Letang, E.; Lovane, L.; Jordao, D.; et al. Clinico-pathological discrepancies in the diagnosis of causes of death in adults in Mozambique: A retrospective observational study. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0220657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazeikiene, S.; Laima, S.; Chmieliauskas, S.; Fomin, D.; Andriuskeviciute, G.; Markeviciute, M.; Matuseviciute, A.; Jasulaitis, A.; Stasiuniene, J. Deontological examination: Clinical and forensic medical diagnoses discrepancies. Egyptian Journal of Forensic Sciences 2016, 6, 323–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehler, S.A. Case Reports: An Important Source of Data for Forensic Medicine and Forensic Pathology. J Crim Forensic studies 2018, 1, 180020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meilia, P.D.I.; Herkutanto; Atmadja, D.S.; Cordner, S.; Eriksson, A.; Kubat, B.; Kumar, A.; Payne-James, J.J.; Rubanzana, W.G.; Uhrenholt, L.; et al. The PERFORM-P (Principles of Evidence-based Reporting in FORensic Medicine-Pathology version). Forensic Sci Int 2021, 327, 110962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fyfe, S.; Williams, C.; Mason, O.J.; Pickup, G.J. Apophenia, theory of mind and schizotypy: perceiving meaning and intentionality in randomness. Cortex 2008, 44, 1316–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldfarb, B.; King, A.A. Scientific apophenia in strategic management research: Significance tests & mistaken inference. Strategic Management Journal 2016, 37, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- sabor, H. Zakon o zdravstvenoj zaštiti. Available online: https://narodne-novine.nn.hr/clanci/sluzbeni/2018_11_100_1929.html (accessed on November 14th).

- Gold, E.R. Body parts: Property rights and the ownership of human biological materials; Georgetown University Press: 1996. [CrossRef]

- Seale, C.; Cavers, D.; Dixon-Woods, M. Commodification of body parts: By medicine or by media? Body & Society 2006, 12, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, R.; Harrison, R.; Start, R.; Chetwood, A.; Chesshire, A.M.; Reed, M.; Cross, S.S. Ownership and uses of human tissue: what are the opinions of surgical in-patients? Journal of clinical pathology 2008, 61, 322–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayor, S. One in four autopsy reports in UK is substandard, report finds. Bmj 2006, 333, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarwar, S.; Shafi, M.I. National Confidential Enquiry into Patient outcome and death. Obstetrics, Gynaecology & Reproductive Medicine 2007, 17, 278–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, S.; Cooper, H.; Emmett, S.; Hargraves, C.; Mason, M. The coroner’s autopsy: do we deserve better. London: National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death 2006.

- Scraton, P.; McNaull, G. Death Investigation, Coroners’ Inquests and the Rights of the Bereaved. 2021.

- Fox, R. Bristol scandal. Circulation 2001, 104, E9014–9014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, P. The Bristol royal infirmary inquiry: the issue explained. The Guardian 2002.

- Coney, S. New Zealand: organ donor registry in jeopardy. Lancet 1989, 2, 1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Streat, S.; Silvester, W. Organ donation in Australia and New Zealand--ICU perspectives. Crit Care Resusc 2001, 3, 48–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauchner, H.; Vinci, R. What have we learnt from the Alder Hey affair? That monitoring physicians' performance is necessary to ensure good practice. BMJ 2001, 322, 309–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, D. The human tissue act 2004. The Modern Law Review 2005, 68, 798–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavroforou, A.; Giannoukas, A.; Michalodimitrakis, E. Consent for organ and tissue retention in British law in the light of the Human Tissue Act 2004. Med Law 2006, 25, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cecchetto, G.; Bajanowski, T.; Cecchi, R.; Favretto, D.; Grabherr, S.; Ishikawa, T.; Kondo, T.; Montisci, M.; Pfeiffer, H.; Bonati, M.R.; et al. Back to the Future - Part 1. The medico-legal autopsy from ancient civilization to the post-genomic era. Int J Legal Med 2017, 131, 1069–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutchinson, E.F.; Kramer, B.; Billings, B.K.; Brits, D.M.; Pather, N. The law, ethics and body donation: A tale of two bequeathal programs. Anatomical sciences education 2020, 13, 512–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manning, J. Changing to Deemed Consent for Deceased Organ Donation in the United Kingdom: Should Australia and New Zealand Follow? J Law Med 2020, 27, 513–526. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Raut, A.; Andrici, J.; Severino, A.; Gill, A.J. The death of the hospital autopsy in Australia? The hospital autopsy rate is declining dramatically. Pathology 2016, 48, 645–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forest, F.; Duband, S.; Peoc'h, M. The attitudes of patients to their own autopsy: a misconception. Journal of clinical pathology 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doldissen, A.; Severino, A.; Bourne, D.; Gill, A. 8. The hospital autopsy rate has fallen dramatically. Pathology 2011, 43, S91–S92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, D.J.; Graves, D.J.; Landgren, A.J.; Lawrence, C.H.; Lipsett, J.; MacGregor, D.P.; Sage, M.D. The decline of the hospital autopsy: a safety and quality issue for healthcare in Australia. Medical Journal of Australia 2004, 180, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warner, J.H.; Rizzolo, L.J. Anatomical instruction and training for professionalism from the 19th to the 21st centuries. Clinical Anatomy 2006, 19, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, L.S.; Meehan, M.C. A history of the autopsy. A review. The American journal of pathology 1973, 73, 514–544. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bauchner, H.; Vinci, R. What have we learnt from the Alder Hey affair? That monitoring physicians' performance is necessary to ensure good practice. BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 2001, 322, 309–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasini, F. Remembering and disremembering the dead: Posthumous punishment, harm and redemption over time; Springer Nature: 2017. [CrossRef]

- Castledine, G. The repercussions of the organ retention scandal. British Journal of Nursing 2001, 10, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seale, C.; Cavers, D.; Dixon-Woods, M. Commodification of body parts: by medicine or by media? Body & Society 2006, 12, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, I. Beyond organ retention: the new human tissue bill. Lancet 2004, 364 Suppl 1, s42–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radunz, S.; Benkö, T.; Stern, S.; Saner, F.H.; Paul, A.; Kaiser, G.M. Medical students’ education on organ donation and its evaluation during six consecutive years: results of a voluntary, anonymous educational intervention study. European Journal of Medical Research 2015, 20, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkas, M.; Anık, E.G.; Demir, M.C.; İlhan, B.; Akman, C.; Ozmen, M.M.; Aksu, N.M. Changing Attitudes of Medical Students Regarding Organ Donation from a University Medical School in Turkey. Med Sci Monit 2018, 24, 6918–6924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khiani, R.; Shingler, S.; Hasleton, P. Consent for autopsy. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 2003, 96, 53–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenbaum, G.E.; Burns, J.; Johnson, J.; Mitchell, C.; Robinson, M.; Truog, R.D. Autopsy consent practice at US teaching hospitals: results of a national survey. Archives of internal medicine 2000, 160, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lishimpi, K.; Chintu, C.; Lucas, S.; Mudenda, V.; Kaluwaji, J.; Story, A.; Maswahu, D.; Bhat, G.; Nunn, A.J.; Zumla, A. Necropsies in African children: consent dilemmas for parents and guardians. Archives of disease in childhood 2001, 84, 463–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, T.N.; Escoffery, C.T.; Shirley, S.E. Necropsy request practices in Jamaica: a study from the University Hospital of the West Indies. Journal of clinical pathology 2002, 55, 608–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elger, B.S.; Hofner, M.-C.; Mangin, P. Research involving biological material from forensic autopsies: legal and ethical issues. Pathobiology 2009, 76, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarnacka, E. Models of the Legal Construct of Consent for Post Mortem organ Transplantation Illustrated by the Example of Poland, Norway and USA. Review of European and Comparative Law 2017, 29, 47–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, M.J.; Woodford, N.W. Objections to medico-legal autopsy--recent developments in case law. J Law Med 2007, 14, 463–468. [Google Scholar]

- Cascella, M.; Rajnik, M.; Aleem, A.; Dulebohn, S.C.; Di Napoli, R. Features, Evaluation, and Treatment of Coronavirus (COVID-19). In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing.

- Copyright © 2023, StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island (FL), 2023.

- Nguyen, T.; Duong Bang, D.; Wolff, A. 2019 Novel Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): Paving the Road for Rapid Detection and Point-of-Care Diagnostics. Micromachines (Basel) 2020, 11, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Gong, Y. Teamwork and Patient Safety in Intensive Care Units: Challenges and Opportunities. Stud Health Technol Inform 2022, 290, 469–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esper, A.M.; Arabi, Y.M.; Cecconi, M.; Du, B.; Giamarellos-Bourboulis, E.J.; Juffermans, N.; Machado, F.; Peake, S.; Phua, J.; Rowan, K.; et al. Systematized and efficient: organization of critical care in the future. Crit Care 2022, 26, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conley, C.E. Student nurses' end-of-life and post mortem care self-efficacy: A descriptive study. Nurse Educ Today 2023, 121, 105698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mort, T.C.; Yeston, N.S. The relationship of pre mortem diagnoses and post mortem findings in a surgical intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 1999, 27, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rusu, S.; Lavis, P.; Domingues Salgado, V.; Van Craynest, M.P.; Creteur, J.; Salmon, I.; Brasseur, A.; Remmelink, M. Comparison of antemortem clinical diagnosis and post-mortem findings in intensive care unit patients. Virchows Arch 2021, 479, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimopoulos, G.; Piagnerelli, M.; Berre, J.; Salmon, I.; Vincent, J.L. Post mortem examination in the intensive care unit: still useful? Intensive Care Med 2004, 30, 2080–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pastores, S.M.; Dulu, A.; Voigt, L.; Raoof, N.; Alicea, M.; Halpern, N.A. Premortem clinical diagnoses and postmortem autopsy findings: discrepancies in critically ill cancer patients. Crit Care 2007, 11, R48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashi, H.; Sasajima, H.; Takayanagi, Y.; Kanamaru, H. International standardization for smarter society in the field of measurement, control and automation. In Proceedings of the 2017 56th Annual Conference of the Society of Instrument and Control Engineers of Japan (SICE), 2017; pp. 263-266. [CrossRef]

- Carayannis, E.G.; Morawska-Jancelewicz, J. The Futures of Europe: Society 5.0 and Industry 5.0 as Driving Forces of Future Universities. Journal of the Knowledge Economy 2022, 13, 3445–3471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Liu, X.; Cao, X.; Huang, C.; Liu, E.; Qian, S.; Liu, X.; Wu, Y.; Dong, F.; Qiu, C.W.; et al. Artificial intelligence: A powerful paradigm for scientific research. Innovation (Camb) 2021, 2, 100179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Wang, Y.; Byrne, R.; Schneider, G.; Yang, S. Concepts of Artificial Intelligence for Computer-Assisted Drug Discovery. Chem Rev 2019, 119, 10520–10594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergi, C.M. Digital pathology: the time is now to bridge the gap between medicine and technological singularity. In Interactive Multimedia-Multimedia Production and Digital Storytelling; IntechOpen London, UK: 2019. [CrossRef]

- Jaillant, L.; Caputo, A. Unlocking digital archives: cross-disciplinary perspectives on AI and born-digital data. AI Soc 2022, 37, 823–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ries, T.; Palkó, G. Born-digital archives. 2019, 1, 1-11.

- Ahmed Alaa El-Din, E. ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE IN FORENSIC SCIENCE: INVASION OR REVOLUTION? Egyptian Society of Clinical Toxicology Journal 2022, 10, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A. Biochemical and physiological research on the disposition and fate of ethanol in the body. Medico legal aspects of alcohol, 5th edition, Lawyers and Judges publishing company, Tucson 2008.

- Jones, A.W. Alcohol, its analysis in blood and breath for forensic purposes, impairment effects, and acute toxicity. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Forensic Science 2019, 1, e1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.W. Driving under the influence of alcohol. Handbook of Forensic Medicine 2022, 3, 1387–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, K.; Mijwil, M.M.; Al-Mistarehi, A.-H.; Alomari, S.; Gök, M.; Alaabdin, A.M.Z.; Abdulrhman, S.H. Has the Future Started? The Current Growth of Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning, and Deep Learning. Iraqi Journal for Computer Science and Mathematics 2022, 3, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, A.M.; Jotterand, F. Doctor ex machina: A critical assessment of the use of artificial intelligence in health care. In Proceedings of the The Journal of Medicine and Philosophy: A Forum for Bioethics and Philosophy of Medicine; 2022; pp. 155–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantic, I.; Paunovic, J.; Cumic, J.; Valjarevic, S.; Petroianu, G.A.; Corridon, P.R. Artificial neural networks in contemporary toxicology research. Chem Biol Interact 2023, 369, 110269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrvar, S.; Himmel, L.E.; Babburi, P.; Goldberg, A.L.; Guffroy, M.; Janardhan, K.; Krempley, A.L.; Bawa, B. Deep Learning Approaches and Applications in Toxicologic Histopathology: Current Status and Future Perspectives. J Pathol Inform 2021, 12, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raju, B.; Jumah, F.; Ashraf, O.; Narayan, V.; Gupta, G.; Sun, H.; Hilden, P.; Nanda, A. Big data, machine learning, and artificial intelligence: a field guide for neurosurgeons. J Neurosurg 2020, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, P.S. Expert Robot: Using Artificial Intelligence to Assist Judges in Admitting Scientific Expert Testimony. Albany Law Journal of Science & Technology 2014, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Whitford, A.B.; Yates, J.; Burchfield, A.; Anastasopoulos, J.L.; Anderson, D.M. The Adoption of Robotics by Government Agencies: Evidence from Crime Labs. Public Administration Review 2020, 80, 976–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujtaba, G.; Shuib, L.; Raj, R.G.; Rajandram, R.; Shaikh, K.; Al-Garadi, M.A. Automatic ICD-10 multi-class classification of cause of death from plaintext autopsy reports through expert-driven feature selection. PloS one 2017, 12, e0170242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, M.; Cho, H.N.; Bhang, S.Y.; Hwang, J.W.; Park, E.J.; Lee, Y.J. Development and a Pilot Application Process of the Korean Psychological Autopsy Checklist for Adolescents. Psychiatry Investig 2018, 15, 490–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shkrum, M.J.; Kent, J. An Autopsy Checklist: A Monitor of Safety and Risk Management. Am J Forensic Med Pathol 2016, 37, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, J.L.; Underwood, J. Clinical, educational, and epidemiological value of autopsy. The Lancet 2007, 369, 1471–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beukes, C. The Autopsy in the 21st Century. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Chariot, P.; Witt, K.; Pautot, V.; Porcher, R.; Thomas, G.; Zafrani, E.S.; Lemaire, F. Declining autopsy rate in a French hospital: physicians' attitudes to the autopsy and use of autopsy material in research publications. Archives of pathology & laboratory medicine 2000, 124, 739–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebert, J.R. Increasing the efficiency of autopsy reporting. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2009, 133, 1932–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- . [CrossRef]

- Rokoske, F.S.; Schenck, A.P.; Hanson, L.C. The potential use of autopsy for continuous quality improvement in hospice and palliative care. The Medscape Journal of Medicine 2008, 10, 289. [Google Scholar]

- Loughrey, M.; McCluggage, W.; Toner, P. The declining autopsy rate and clinicians' attitudes. The Ulster medical journal 2000, 69, 83. [Google Scholar]

- Ayoub, T.; Chow, J. The conventional autopsy in modern medicine. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 2008, 101, 177–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, A.J.; Field, C.L.; Hoopes, L.A.; Clauss, T.M. Medical Management of Coelomic Distention, Abnormal Swimming, Substrate Retention, and Hematologic Changes in a Reef Manta Ray (Manta Alfredi). J Zoo Wildl Med 2016, 47, 927–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| major discrepancies | class l | discrepancies in primary diagnoses with relation to cause of death - detection would have led to changes in management and therapy |

| class ll | discrepancies in major diagnoses about the cause of death - detection and adjusted therapy (management changes) could have prolonged survival or cured the patient. | |

| minor discrepancies | class all | Symptoms should have been treated or would have eventually affected the prognosis. |

| class IV | Non-diagnosable (occult) diseases with possible genetic or epidemiological importance. | |

| class V | non-classifiable cases |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).