1. Introduction

The construction industry is a cornerstone of societal progress in building infrastructure. Yet, amidst its pivotal contributions, it also poses a major environmental pollution. This sector is responsible for approximately 70–80% of the total particulate matter (PM) emissions into the atmosphere [

1,

2]. The ramifications of this issue are concerning for the health of construction workers who are regularly exposed to construction-related dust. This exposure carries both short-term and long-term health risks (HR), contributing to health issues within this labor-intensive field [

3]. The challenges are aggravated by the demographic trend of an aging workforce in the construction industry. This risk is more pronounced in construction than in other industries like automotive manufacturing, biomass combustion, and power generation [

2].

Despite considerable advancements in occupational health and safety, the construction sector continues to grapple with significant HR [

4]. Research has identified common construction activities such as drilling, cutting, sanding, and mixing as the primary culprits in PM emissions [

5]. These activities, integral to construction processes, inadvertently contribute to the elevated levels of airborne particulates.

The health implications of PM exposure are extensive and varied. Diseases like asthma, cardiovascular disorders, silicosis, lung cancer, and other pulmonary conditions have been directly associated with PM exposure [

6]. The complex chemical makeup of PM, consisting of elements such as aluminum (Al), chlorine (Cl), iron (Fe), magnesium (Mg), potassium (K), sulfur (S), silicon (Si), lead (Pb), cadmium (Cd), zinc (Zn), and copper (Cu), has been underscored in various studies [

6,

7,

8] as a significant HR. For instance, overexposure to lead can result in adverse effects on the nervous, skeletal, endocrine, and immune systems [

9]. Similarly, excessive inhalation of copper is known to be linked with severe respiratory conditions, including chronic bronchitis, asthma, and lung cancer [

10,

11].

While numerous studies [

1,

4,

6,

7] have endeavored to evaluate and mitigate the HR associated with PM and toxic substances (TS), achieving precision in these investigations remains a challenge. For example, traditional land-based PM HR assessments [

3] concluded the uniform PM concentration across construction sites. This assumption oversimplifies the complexity of the environment and overlooks the necessity of activity-specific HR evaluations. More recent research has begun to address this gap by considering in different construction activities to gather more accurate PM HR emission data. Nonetheless, these studies frequently neglect the impact of varied construction materials and TS on HR [

11]. For example, Li et al.'s [

6] approach, which examined dust exposure across 33 construction sites and assessed only one material type per sample, differs from the simulation findings of Cheriyan et al. [

12]. The latter study illustrated that PM emissions could exhibit significant variation based on the specific construction materials employed.

The growing recognition among researchers since the early 2000s emphasizes the need for a unified PM emission dataset for the construction sector. This dataset is essential for effectively analyzing and mitigating the health impacts associated with PM and TS exposure [

11]. In response, previous studies [

13,

14] have embarked on simulations involving a variety of construction activities and materials. The outcomes of these simulations, referred to as 'experimental databases' in this study, have been standardized to foster further research and application.

In the midst of this evolving landscape, our research has developed a process for determining a PM and TS Health Risk Index (HRI), based on a model recommended by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). This HRI is meticulously designed to aid construction managers in identifying and addressing the HR associated with specific construction activities.

Moreover, it is vital that the insights provided by the HRI are presented in a format that is both comprehensible and actionable. To this end, Building Information Modeling (BIM) emerges as a highly effective tool. BIM is renowned for its ability to manage complex building projects and facilitate detailed visualization in both 2D and 3D formats throughout the construction process [

15]. Its capacity for fostering active collaboration among project stakeholders has been well-documented, and its role in construction health and safety risk management has been increasingly recognized [

15,

16]. By leveraging the advanced technological capabilities of BIM, its high visualization potential, and its widespread application in the construction industry, we have developed a specialized Revit plugin. This plugin is designed to streamline the HRI determination process, thereby substantially enhancing health management for workers involved in construction projects.

2. Literature review

2.1. Occupational HR assessment of PM and TS in the construction industry

Increasing awareness of HR associated with exposure to PM and TS in construction activities is evident in recent studies. A select group of researchers [

3,

8,

17] have delved into HR assessments specific to construction, forging a deeper understanding of the link between HR and pollutants produced by these activities. This section navigates through some literature, unraveling the key findings and insights garnered by researchers who have delved into the complex interplay between construction activities and health hazards.

De Moraes et al. [

18] undertook an empirical study across five building sites, scrutinizing PM and total suspended particles (TSP) emissions emanating from concrete and masonry work. This study sheds light on the characteristics and composition of PM at construction sites, including the impact of meteorological variables and construction activities on PM concentration, while also acknowledging the limitations inherent in the research.

In another significant study, Latif et al. [

5] assessed the exposure to various TS during renovation tasks like demolition, drilling, sanding, cutting, and painting in a controlled laboratory setting. Here, PM

10 concentrations were observed to surpass the dust limit set by the Malaysian Department of Safety and Health (DOSH) in indoor environments (150 g/m

3), ranging from 166 µg/m3 to 542 µg/m3. Four TS (Pb, Cd, Zn, and Cu) were identified, with Zn being the most prevalent, followed by Cu, Pb, and Cd. These findings are attributed to the composition of building materials and furnishings used during the renovation.

Tong et al. [

19] explored the impact of construction dust on worker health across five different zones during the superstructure construction stage of residential projects in Beijing. Utilizing the USEPA risk assessment model, the Monte-Carlo method, and a probabilistic risk assessment model, the study estimated the HR attributable to construction dust, pinpointing the most significant parameters. The results indicated varying levels of construction dust-induced HR across zones, in the order of: template zone > steel zone > concrete area > floor zone > office zone. The study highlighted the elevated HR in the template zone, emphasizing the need for effective control measures to mitigate the adverse health effects of construction dust.

In summary, recent scholarly discourse demonstrates a growing awareness of HR associated with exposure to PM and TS in construction activities. The examination of HR linked to TS in this context remains limited. Furthermore, to achieve a comprehensive HR assessment, it is essential to integrate detailed information concerning the specific types of activities and materials involved in construction processes.

2.2. PM and TS database from previous studies

Choi et al. [

14] employed the USEPA equation to evaluate the HR associated with PM and TS generated by construction activities, integrating real-time inhalation rate (IR) measurements into their analysis. A series of methodical experimental simulations were conducted to assess the HR linked to various construction activities and materials. This research built upon the experimental framework outlined by Cheriyan et al. [

20], with a focused revision towards prioritizing PM

10 particles. Monitoring stations were strategically placed one meter from the PM source to facilitate construction operations while ensuring accurate data collection. The experiments were executed within a dust chamber measuring 4 x 4 x 2.35m

3, featuring walls and floors lined with adhesive mats that were moistened to reduce particle deflection.

The partition wall and sensors were positioned one meter apart, with a 3 x 0.7m

2 observation window facilitating external monitoring of the experiments. Activities typical of a construction setting, such as cutting, drilling, mixing, sanding, and plastering, were simulated using materials like wood, hollow blocks, solid blocks, and M20 and M25 grade substances. To account for PM particle settling time, each activity was spaced with a 24-hour interval, and baseline levels were reassessed at similar intervals. If PM levels exceeded the reference threshold, the experiment was deferred to the next day. The PM concentrations emitted during these activities were meticulously monitored, alongside fluctuations in the IR of construction workers. Data were systematically collected and stored using a computer, with results adapted and revised from Cheriyan et al. [

20], as delineated in

Table 1 and

Table 2.

Given the unavailability of real-time TS monitoring equipment, this study embraced the gravimetric sampling methodology recommended by Khamraev et al. [

21] for estimating real-time TS levels. PM collection was also executed using the MiniVol device [

22] to ascertain the composition of TS in various activities. During the solid block cutting, real-time (Alphasense OPC-N3) PM monitoring and gravimetric samplers were deployed concurrently. The diverse TS were identified by analyzing dust samples from this activity. Since the material compositions in the assorted activities were consistent, the ratios derived from the solid block cutting were extrapolated to other activities, a methodology also derived from [

23] (

Table 3).

2.3. BIM application for health management in construction project

BIM brings forth a myriad of advantages, notably in enhancing stakeholder collaboration, boosting production efficiency, and elevating revenue generation [

24]. An extensive review of pertinent literature [

15,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30] underscores numerous endeavors to amalgamate various BIM functionalities for the effective management of health and safety risks. The salient benefits derived from integrating health and safety risk management within BIM frameworks are concisely summarized in

Table 4. Recent years have witnessed the evolution of health and safety management systems grounded in BIM technology. These systems primarily serve to streamline the identification and communication of risk factors, significantly mitigate safety hazards for personnel, and augment overall quality, safety, and efficiency in project time and budget management.

A particularly notable contribution to HR management in the construction sector was made by Xu et al. [

26]. This study expanded the scope of air pollutant monitoring through the integration of edge computing and a sensor network interface module with BIM. This innovative approach significantly enhances the capability for storing and analyzing sensor data, enabling the effective visualization of rapid changes in air pollution concentrations in real-time, along with incorporating predictive functionalities into the system. This methodology represents a groundbreaking approach to air quality monitoring and emergency management on construction sites. However, it is important to note that Xu et al.'s research primarily focuses on improving overall site environment emergency management, rather than directly addressing worker health.

In a parallel vein, Riaz et al. [

24] developed a prototype that marries BIM with wireless sensor technology to prevent fatalities and serious injuries in confined spaces due to hazardous environmental exposures. This system utilizes Revit software for the visualization of sensor data, allowing users to pinpoint the precise locations of sensors within a building structure. The integration of real-time sensor data with BIM emerges as a powerful application for enhancing the health and safety management of construction workers, demonstrating the potential of modern technology in mitigating occupational hazards.

A thorough review of literature pertaining to the application of BIM in the construction industry underscores its increasing utilization, particularly concerning safety management in construction projects. Notably, studies [

27,

28] referenced in

Table 4 illustrate applications such as health monitoring of structural integrity and noise distribution analysis through BIM integration. Despite these advancements, a comprehensive survey of the literature, including the seminal works listed in

Table 4, indicates that the full potential of BIM in assessing and mitigating workers’ health risks remains largely untapped. This gap in application is attributed to the absence of a standardized database for PM and TS. The deficiency of such a foundational dataset limits the ability to effectively leverage BIM for evaluating occupational health risks and devising appropriate preventive strategies.

3. Methodology

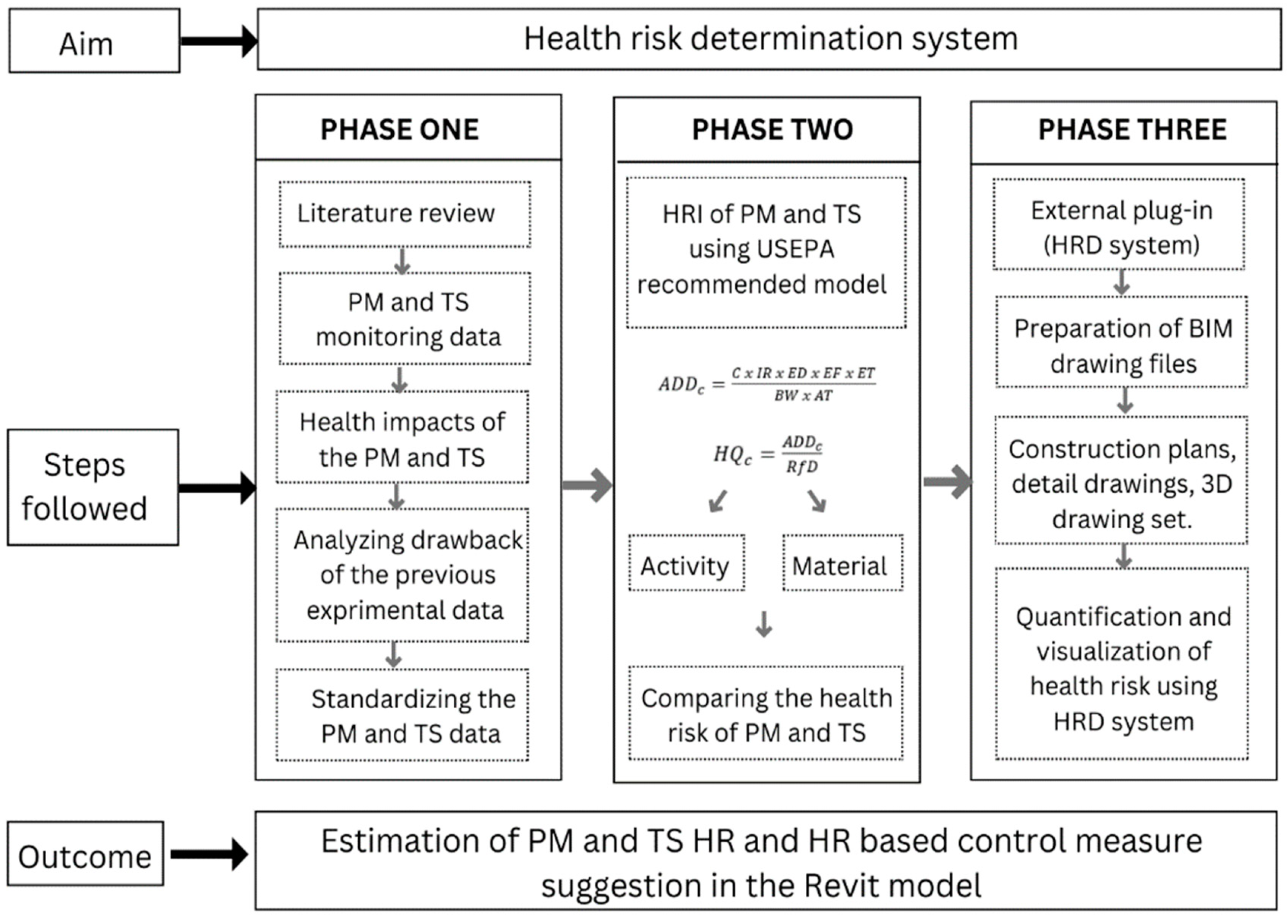

In the pursuit of advancing occupational health in construction, a methodical and practical approach was employed to develop a predictive system for HR. This involved a step-by-step process as illustrated in

Figure 1. To develop an HRI, we utilized previously published data of PM and TS, aiming to a standardized database which can be used as standardized data to predict the HR. This was conducted in strict accordance with the HR model outlined by the USEPA. For practical implementation, it was imperative that this system seamlessly integrates with the BIM model of any given construction project, highlighting HR concerns. Consequently, the authors developed a Revit-based plugin, capable of extracting the newly formulated HRI and interfacing it with the building plan, thereby enabling the delineation of HR values for specific construction activities and respective control measures. The following sections provide an in-depth description of each step in this process.

3.1. Phase I - Standardization of PM and TS experimental data

This study rigorously evaluates the existing literature from reputable journals on HR assessments related to PM and TS, as delineated in the literature review section. This review highlights the necessity for experimental data on PM and TS, involving diverse materials, to be available in a standardized format to facilitate the creation of an HRI. Accordingly, this research develops a comprehensive database that includes variations in both PM and TS, referencing [

14,

20]. The standardized PM and TS data were then transformed into volumetric units (m³). Elements or activities based on volume were adjusted to m³, while those based on area were converted to m². For example, in drilling activities across various materials, the dimensions of the drill hole (10 mm diameter and 25.4 mm depth) were consistent, yielding a volume of 0.00797 m³ per hole. Given that each solid block was marked for 50 holes, the standardized PM

1 data for drilling into solid blocks was calculated as 0.1348 mg/m³. This methodology was similarly employed for other activities and materials. The results of this standardization are systematically illustrated in

Table 5,

Table 6,

Table 7 and

Table 8.

3.2. Phase 2 - PM and TS HRI

To quantify the HR associated with the standardized PM and TS data, the methodology prescribed by the USEPA was employed [

31].

In this equation, 'C' denotes the concentration of pollutants, namely PM and TS (mg/m³), 'IR' represents the inhalation rate (m³/h), 'ED' stands for exposure duration (years), 'ET' refers to exposure time (hours), 'EF' indicates exposure frequency (days/year), 'BW' is body weight (kg), and 'AT' signifies the average time (years). Following this, the hazard quotient for each PM category was determined using the subsequent equation as per guidelines in [

31].

The term 'RfD' refers to the reference dose for non-carcinogenic substances, expressed in mg/kg × day (d

−1). RfD represents the threshold dose at which adverse health effects are observed, with doses below RfD typically not associated with adverse health impacts. The RfD values employed in this study's calculations, drawn from USEPA references, vary for different types of construction dust: 0.4 for silica dust, 1.2 for cement dust, 1.6 for wood dust, and 3.2 for plaster dust [

32]. In a parallel methodology, a similar approach was adopted to determine standardized TS HR values using the aforementioned equations.

3.3. Phase 3 - Health risk determination (HRD) BIM plug-in system architecture and function

In the vanguard of innovative construction safety, this study propounds a BIM-based system named 'Health Risk Determination (HRD).' This system seamlessly integrates the USEPA calculation method incorporating authors suggested standardized HRI values for PM and TS within BIM. This heralds a transformative era in mitigating HR for workers involved in construction projects. This section provides a comprehensive overview of the system architecture and functionalities of the HRD.

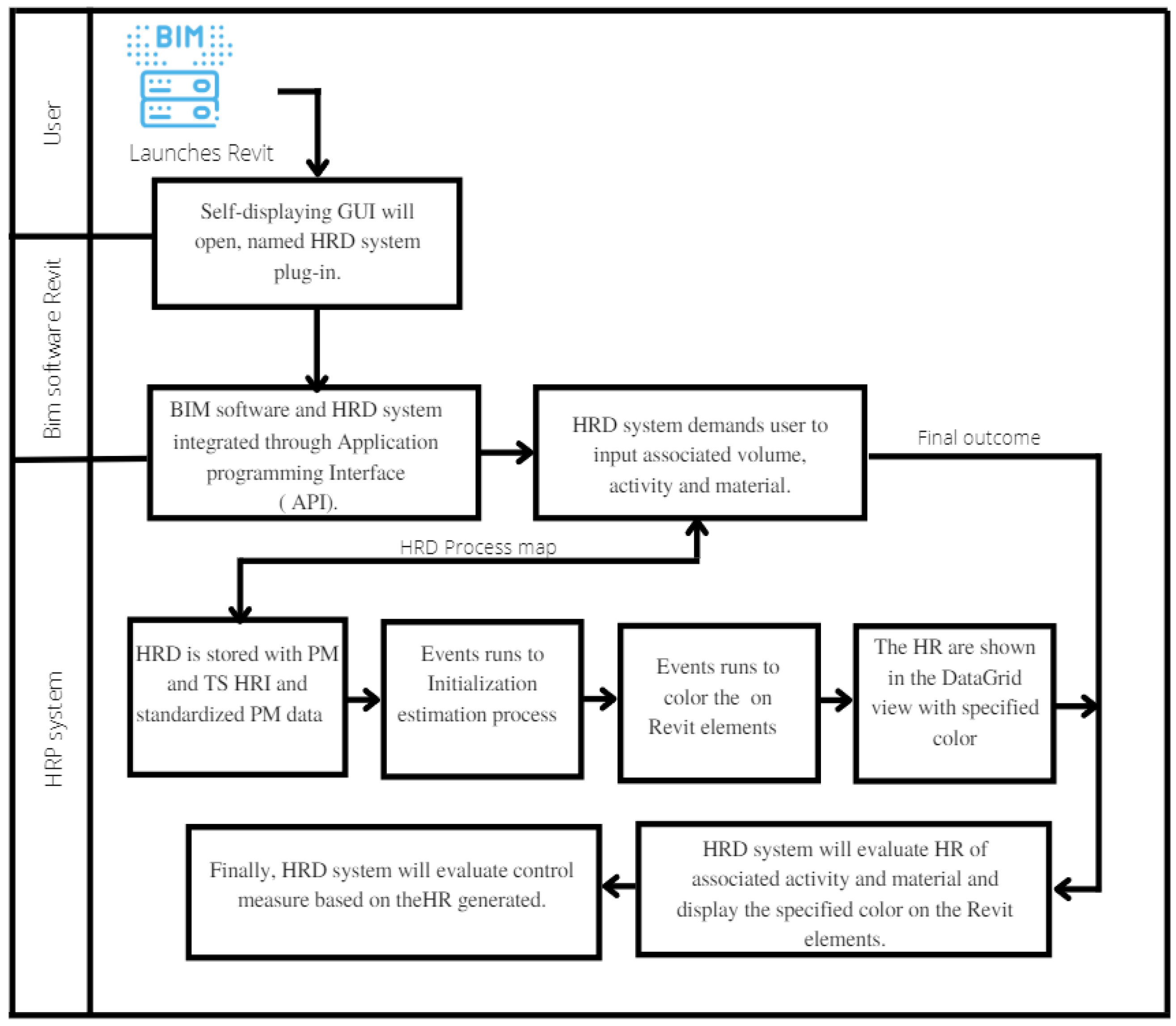

The very essence of the HRD system lies in its meticulously designed system architecture. The choice of the Visual Studio.Net as development platform was made, which permits programming within Revit using Revit Application Programming Interface (API). This interface acts as the communication bridge, enabling HRD to dynamically interface with the voluminous data and complex elements within the BIM model. HRD's operates through a self-updating graphical user interface (GUI), as a Revit plug-in. This external application integrates into the Revit software, serving as the portal through which users interact with the functionalities of HRD. The C# programming language was chosen as the coding language. The coding intricacies reflect a commitment to precision, ensuring that HRD's algorithms operate with a quantitative framework deeply rooted in the methodologies advocated by the USEPA (refer to 3.2 section). HRD adeptly leverages this framework, ensuring that calculations adhere to its standards.

Recognizing the importance of user-friendly guidance, HRD incorporates an interaction ensures that stakeholders, irrespective of technical proficiency, can navigate HRD with confidence. The plugin's interface begins with an installation process onto major BIM platforms (Revit) ensuring accessibility across the construction industry. Upon launching the HRD plugin, Users are guided to input relevant volume data and choose materials of designate element from the BIM model necessitating subsequent calculation. Further, the system architecture plays a pivotal role in empowering the plugin to conduct HR calculations within the model. The integration of this database allows for a detailed and accurate representation of HR factors associated with specific construction activity and materials, enhancing the overall efficacy of the HRD system.

Following the intricate calculations within the HRD system, a series of consequential actions are set to enhance HR management in construction projects. Within the BIM model, HR assessments are visually conveyed through a sophisticated color-coded system. Specific color filters and coding correspond to different risk levels, providing a visual representation of HR associated with each element.

The quantified HR within the BIM model is visualized using a color-coded system. Specific color filters and coding are established to correspond with different risk levels, allowing for the application of parameters based on the value of the risk. The color associated with a building element reflects the calculated HR. Additionally, the HRD system implements tailored control measures on elements, guided by the severity of the calculated HR. Facilitating this process involves the integration of a specialized control measure library directly into the BIM model. BIM's inherent capability to incorporate both the geometry and semantics of building components plays a pivotal role. Semantics in BIM enhance the 3D building model by specifying the properties and attributes of each building component [

33]. This integration is achieved through the creation of URL-type parameters linked with individual BIM elements, empowering the HRD system to seamlessly associate essential HR information with each specific element.

4. HRI ANALYSIS and Results

This section details the HRI analysis, with findings delineated in

Table 9 and

Table 10 for PM and TS ratios, respectively. The risk level assessment adhered to USEPA guidelines: HR values below 10

-6 are considered acceptable and safe, values between 10

-4 and 10

-6 suggest potential HR, and values above 10

-4 indicate severe HR [

32]. The highest HR during drilling was recorded in PM10 for the M25 cement block (1.4 × 10

-6 mg/m³), followed by the M20 cement block (1.1 × 10

-6 mg/m³) and solid block (1.3 × 10

-6 mg/m³). The lowest HR in PM

10 was observed while drilling wood (7.6 × 10

-12 mg/m³). However, the TS HRI exhibited a different pattern, with all activities showing medium risk levels, ranging from 9.6 × 10

-5 mg/m³ in M20 PM10 to 8.3 × 10

-6 mg/m³ in hollow block PM

2.5.

Similarly, during cutting activities, PM HR levels mirrored those in drilling, with the highest and lowest HRs observed in PM10 at 6.7 × 10-5 mg/m³ and PM1 at 0.9 × 10-10 mg/m³, respectively, when cutting wood and hollow block. The highest TS HR was seen in M20 PM10 at 1.5 × 10-3 mg/m³, and the lowest in wood PM10 at 5.4 × 10-6 mg/m³. Sanding M20 and M25 cement blocks in PM10 showed the highest HRs at 1.6 × 10-6 mg/m³ and 2.2 × 10-6 mg/m³, respectively, while the lowest in PM1 was for M20 at 3.1 × 10-9 mg/m³.

The TS HR for sanding activities indicated a medium-risk level across all activities, ranging from 1.4 × 10-4 mg/m³ to 3.5 × 10-6 mg/m³. Mixing activities yielded HR values of 1.6 × 10-5 mg/m³ and 4.5 × 10-8 mg/m³. The highest TS HR in PM10 for M20 cement block was 1.0 × 10-3 mg/m³, and the lowest in PM2.5 for M20 was 7.1 × 10-5mg/m³. Plastering activities indicated low PM HR levels, ranging from 1.1 × 10-7 mg/m³ to 1.0 × 10-8 mg/m³. The overall HR for the cutting of M25 cement block in PM10 was the highest at 4.1 × 10-3 mg/m³, whereas the lowest in PM2.5 for drilling hollow block was 8.3 × 10-6 mg/m³. Consistent results were observed for the TS HR in cutting wood in PM2.5 (4.5 × 10^-5 mg/m³) and PM10 (5.4 × 10-6 mg/m³), showing a minor difference from drilling wood in PM2.5 (4.5 × 10^-6 mg/m³) and PM10 (5.4 × 10-5 mg/m³). The most significant difference was noted in mixing M25 for PM10 and sanding M25 cement block for PM10. The findings indicate that TS HR is higher than PM in all activities and materials, with PM values being 65 times lower than TS. While HR assessments have traditionally emphasized PM, the HRI demonstrates that control measures should also consider TS.

The highest PM HR recorded across all activities was during the cutting of the M20 cement block for PM10, registering at 2.4 × 10-6 mg/m³. Conversely, the lowest PM HR was observed during the cutting of hollow blocks (0.9 × 10-10 mg/m³), which was 3.6 times lower than the highest PM risk level. PM risk levels for PM10, PM2.5, and PM1 during hollow block drilling were found to be 5% lower compared to those during solid block drilling. The risk level values for PM10, PM2.5, and PM1 in the drilling of M20 and M25 cement blocks were 9.1 × 10-9 mg/m³, 1.1 × 10-7 mg/m³, 1.1 × 10-6 mg/m³, and 1.6 × 10-7 mg/m³, 1.6 × 10-7 mg/m³, 1.4 × 10-6 mg/m³, respectively, showing a variance of 6.8%. Despite the relatively small 5% difference in PM concentrations between hollow block and solid block drilling, cutting the same materials displayed significant variations in PM concentrations.

PM HR values for cutting solid blocks were 10% higher than those for cutting hollow blocks. A similar trend was observed in PM risk values from cutting M20 and M25 cement blocks, mirroring the drilling activity patterns. Notably, PM risk levels during the sanding of M25 cement blocks were 9% higher than those for M20 cement blocks. These findings underscore that the HR associated with PM and TS varies depending on the materials used in construction activities. The results indicate that higher-density materials, such as the M25 cement block, exhibit higher HR, whereas lower-density materials like wood present lower HR.

5. Illustrative case example

5.1. Project information

This illustrative case study is designed to validate the applicability of the HRD system. The study integrates the HRI determination process into the realm of BIM. This integration is expertly facilitated by the advanced functionalities encapsulated within the HRD plugin. The library building renovation project was chosen for this case study, due to the intrinsic challenges associated with renovation works that involve diverse materials and activities. Moreover, renovation projects inherently introduce a multitude of indoor air pollutants into the environment, including PM, heavy metals, fibrous materials, various gaseous emissions, and a spectrum of organic compounds [

3].

This case study focuses on the renovation of a 300,000-square-foot library spanning five floors. The project, unfolding over one week, includes diverse tasks such as selective demolition, plumbing, masonry work, and electrical installations across the second to fourth floors. The principal activities of the renovation involve comprehensive structural modifications and upgrades, including the dismantling and reinstallation of windows, doors, and tiling, the revamping of bathroom fixtures like sinks and toilets, and the artistic enhancement of the interior through painting and wall treatments. These broad renovation activities are further subdivided into the tasks such as cutting, sanding, mixing, drilling, and plastering. Various materials like concrete (M20 and M25 grades), building blocks, and wood are employed. This setting provides a detailed context for evaluating the HRD system's application in a complex remodeling scenario.

5.2. Application of the HRD system

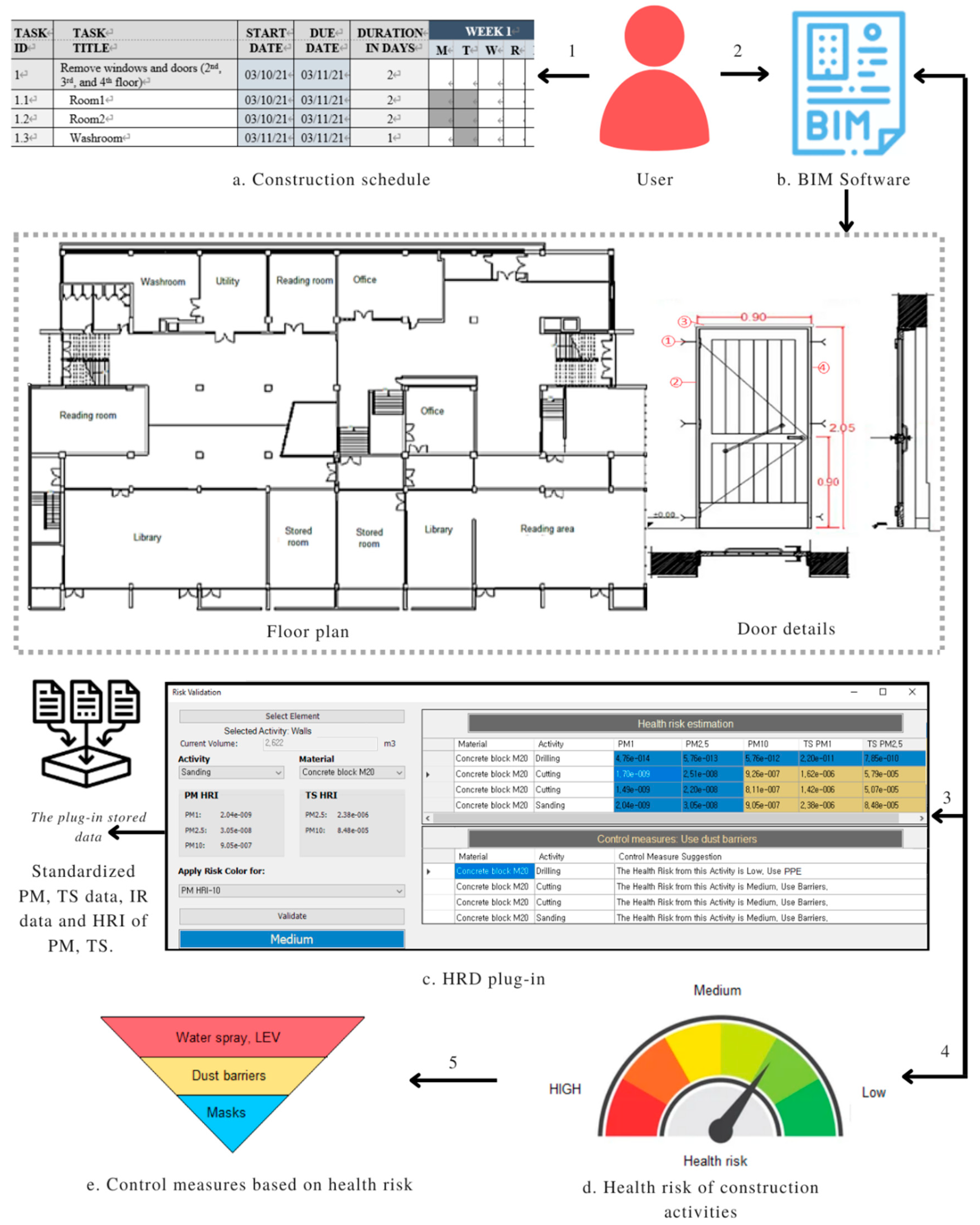

The HRD system's workflow is visually outlined in

Figure 3, providing a clear overview of the sytem. To initiate the process, the construction supervisor relies on a combination of resources, including the detailed remodeling work schedule and 2D or 3D BIM drawings. These resources offer vital insights into the upcoming activities, enabling the supervisor to pinpoint the specific areas of focus and understand the materials and construction dimensions involved (

Figure 3a,b).

In the practical application of the HRD system, the site supervisor initiates the process by relying on a combination of resources, including a detailed remodeling work schedule and 2D or 3D BIM drawings. These resources offer crucial insights into upcoming activities, allowing the supervisor to identify specific areas of focus and understand the materials and volume involved (

Figure 3a). Furthermore, the supervisor utilizes a specially designed external plugin called the HRD within Revit, developed as a part of this research endeavor. The HR assessment of each daily activity and sub-task can be calculated with the available schedule, materials, and volume (

Figure 3b).

The supervisor gains the ability to evaluate the HR values associated with the day's construction activities and materials (

Figure 3d) by leveraging the plugin's functionalities (

Figure 3c). Armed with this valuable information, the supervisor can make informed decisions and implement control measures as needed to ensure the safety and well-being of the workers (

Figure 3e).

The HRD system's implementation in construction activities is meticulously detailed in

Figure 3, showcasing its integral role in task management. To precisely calculate the HR for specific construction activities, the process begins with a comprehensive analysis of work orders, breaking down each activity into its tasks. For example, the door removal activity is methodically segmented into distinct phases: firstly, drilling out the hinges, followed by chipping out the frame, then removing the lintel, and finally, cleaning the surface. In the task of door removal, the procedure diverges slightly, adhering closely to the detailed drawing of the door as illustrated in

Figure 3b.

The HR calculation, as delineated in the methodology section, is a critical component of this system. Emphasizing on accuracy and detail,

Table 8 in the report presents the outcomes derived from the HRD system. The system's plugin, a pivotal element in this framework, archives the HRI and control measures data, corresponding to varying HR levels. Consequently, the BIM model highlights these elements, showcasing the estimated HR levels in a visually intuitive manner. For example, the HR for the initial task of drilling out the hinges is categorized as low (referenced in

Table 11), prompting the HRD system to color-code the hinges in blue and recommend the usage of personal protective equipment (PPE) as a preventive measure. This color-coding and recommendation process is an innovative approach to ensuring safety and efficiency in construction activities.

5.3. Case study results and discussion

The case study, set in the context of a library building earmarked for remodeling, serves as a hypothetical yet insightful exploration into the capabilities of the HRD system. Within this framework, the daily PM and TS HR levels, emanating from diverse construction activities, were meticulously calculated using the HRP system.

The primary objective of the HRD system is to implement targeted control measures based on the HR levels generated. Activities flagged with high HR levels demand heightened attention. In response, control strategies such as water suppression and Local Exhaust Ventilation (LEV) are recommended, with the potential to mitigate 70-80% of PM and TS HR as per source [

23]. Medium HR levels warrant the installation of dust barriers [

33], whereas low HR levels are deemed safe without additional control measures. Notably, the results from the door activity estimation indicate the necessity for dust barriers during the door removal process.

Contrasting with the conventional HR estimation process, which requires manual input of multiple variables (PM, IR, ED, ET, EF, BW, AT) derived from construction activities and workers’ data, the HRD system introduces a paradigm shift. The conventional approach, often laborious and time-consuming, applies continuous control measures indiscriminately across the construction site. In stark contrast, the semi-automated HRD system leverages 2D or 3D Revit construction drawings and the specialized HRD plugin to quantify HR more efficiently. Consequently, site supervisors can rapidly implement control measures that are finely tuned to address high-risk activities, as evidenced by the case study results. This targeted approach not only quantifies HR at the level of individual activities but also empowers supervisors to promptly adopt control measures for high-risk scenarios.

This study casts a new light on the assessment of HR at the activity and material level in the construction industry. By visualizing the HR associated with daily construction activities, health managers can proactively implement adequate control measures onsite. This innovative system not only aids in current health risk management but also provides a valuable tool for future researchers to predict and mitigate occupational health impairments in the construction industry.

As such, the HRD system was built based on the concept that was first attempted, but it is necessary to continue to build PM and TS data based on various types of work, materials, and construction methods, and additional research efforts are needed to allow the BIM-based HRD system to settle in the work process.

6. Conclusions

This study underscores the pressing issue of health impairments among construction workers, primarily stemming from exposure to PM and TS particles. The systematic methodology introduced a quantitative approach to assess the HR associated with activities with high PM emissions. Drawing upon PM and TS simulation data from previously published articles, the authors meticulously prepared a standardized HRI by transforming them into a standardized format, thus enhancing its applicability and scalability for use in various construction projects. In addition, recognizing the scalability and application of BIM software in the construction industry, the authors developed a specialized HRD system plugin for Revit, thereby enabling the integration of standardized HRI data with BIM. This integration facilitates the quantification of HR at the activity level within the BIM environment.

The illustrative case study within this article clearly demonstrates the efficacy of the BIM-integrated HRD system in estimating HR from specific construction activities. Construction managers can now review HR metrics within Revit alongside ongoing work processes and implement the recommended control measures. This capability not only aids in visualizing but also in mitigating the health impacts to construction workers on construction sites. By enabling the estimation of HR at the activity level, the system empowers health and safety teams to preemptively prepare and implement appropriate control measures.

The findings of this study illuminate the pathway for activity and material-level HR assessment within the construction industry. Experts in the academia-industry field of construction should pay attention to the significant contributions this study has made, which are unprecedented from the perspective of the construction industry. Firstly, the quantification of the health risk of PM and TS and their integration into work processes, and secondly, the expansion of BIM's adaptability into the field of health and safety management, demonstrating its potential applicability across various construction trades. However, it is important to note that the current system relies on a standard database, which, while comprehensive, is limited to certain construction materials and work practices. Therefore, there is a crucial need to expand this database progressively, incorporating a wider array of activities, materials, and equipment to enhance its applicability and effectiveness across diverse construction scenarios.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the Korea Agency for Infrastructure Technology Advancement (KAIA) grant funded by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport (National Research for Smart Construction Technology: Grant 225MIP-A156381-03), and the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (2022R111A3073717).

References

- Apte, J.S.; Brauer, M.; Cohen, A.J.; Ezzati, M.; Pope, C.A.I.I.I. Ambient PM2.5 Reduces Global and Regional Life Expectancy. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2018, 5, 546–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brook, R.D.; Franklin, B.; Cascio, W.; Hong, Y.; Howard, G.; Lipsett, M.; Luepker, R.; Mittleman, M.; Samet, J.; Smith, S.C.; et al. Air Pollution and Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation 2004, 109, 2655–2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPA Risk Assessment Guidance for Superfund. Volume I Human Health Evaluation Manual (Part A). 1989; I, 289.

- Yang, H.; Song, X.; Zhang, Q. RS&GIS Based PM Emission Inventories of Dust Sources over a Provincial Scale: A Case Study of Henan Province, Central China. Atmos. Environ. 2020, 225, 117361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, M.T.; Baharudin, N.H.; Velayutham, P.; Awang, N.; Hamdan, H.; Mohamad, R.; Mokhtar, M.B. Composition of Heavy Metals and Airborne Fibers in the Indoor Environment of a Building during Renovation. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2011, 181, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Fang, C.H.Y.; Shi, W.; Gurusamy, S.; Li, S.; Krishnan, M.N.; George, S. Size and Site Dependent Biological Hazard Potential of Particulate Matters Collected from Different Heights at the Vicinity of a Building Construction. Toxicol. Lett. 2015, 238, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azarmi, F.; Kumar, P.; Mulheron, M. The Exposure to Coarse, Fine and Ultrafine Particle Emissions from Concrete Mixing, Drilling and Cutting Activities. J. Hazard. Mater. 2014, 279, 268–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klotz, K.; Weistenhöfer, W.; Neff, F.; Hartwig, A.; Van Thriel, C.; Drexler, H. The Health Effects of Aluminum Exposure. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2017, 114, 653–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J. A Review of Electrode Materials for Electrochemical Supercapacitors. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 797–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Xia, B.; Fan, C.; Zhao, P.; Shen, S. Human Health Risk from Soil Heavy Metal Contamination under Different Land Uses near Dabaoshan Mine, Southern China. Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 417–418, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muleski, G.E.; Cowherd, C.; Kinsey, J.S. Particulate Emissions from Construction Activities. J. Air Waste Manage. Assoc. 2005, 55, 772–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheriyan, D.; Choi, J. Estimation of Particulate Matter Exposure to Construction Workers Using Low-Cost Dust Sensors. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 59, 102197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheriyan, D.; Khamraev, K.; Choi, J. Varying Health Risks of Respirable and Fine Particles from Construction Works. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 72, 103016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Khamraev, K.; Cheriyan, D. Hybrid Health Risk Assessment Model Using Real-Time Particulate Matter, Biometrics, and Benchmark Device. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 350, 131443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barazzetti, L.; Banfi, F.; Brumana, R.; Previtali, M. Creation of Parametric BIM Objects from Point Clouds Using Nurbs. Photogramm. Rec. 2015, 30, 339–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, A. Building Information Modeling (BIM): Trends, Benefits, Risks, and Challenges for the AEC Industry. Leadersh. Manag. Eng. 2011, 11, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Europe, W.H.O.R.O. for Health Effects of Particulate Matter: Policy Implications for Countries in Eastern Europe, Caucasus and Central Asia; World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen PP - Copenhagen; ISBN 9789289000017.

- Brito, de M. R.J.; Bastos, C.D.; Silva, A.I.P. Particulate Matter Concentration from Construction Sites: Concrete and Masonry Works. J. Environ. Eng. 2016, 142, 5016004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, R.; Cheng, M.; Zhang, L.; Liu, M.; Yang, X.; Li, X.; Yin, W. The Construction Dust-Induced Occupational Health Risk Using Monte-Carlo Simulation. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 184, 598–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheriyan, D.; Hyun, K.Y.; Jaegoo, H.; Choi, J. Assessing the Distributional Characteristics of PM10, PM2.5, and PM1 Exposure Profile Produced and Propagated from a Construction Activity. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 276, 124335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamraev, K.; Cheriyan, D.; Choi, J. A Review on Health Risk Assessment of PM in the Construction Industry – Current Situation and Future Directions. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 758, 143716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldauf, R.W.; Lane, D.D.; Marotz, G.A.; Wiener, R.W. Performance Evaluation of the Portable MiniVOL Particulate Matter Sampler. Atmos. Environ. 2001, 35, 6087–6091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, J.; Wang, Y.; Bäumer, S.; Boersma, A. Inline Infrared Chemical Identification of Particulate Matter. Sensors (Switzerland) 2020, 20, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riaz, Z.; Arslan, M.; Kiani, A.K.; Azhar, S. CoSMoS: A BIM and Wireless Sensor Based Integrated Solution for Worker Safety in Confined Spaces. Autom. Constr. 2014, 45, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timo, H.; Ju, G.; Martin, F. Areas of Application for 3D and 4D Models on Construction Projects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2008, 134, 776–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Ran, Y.; Rao, Z. Design and Integration of Air Pollutants Monitoring System for Emergency Management in Construction Site Based on BIM and Edge Computing. Build. Environ. 2022, 211, 108725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xiao, Y.; Guo, H.; Zhang, J. A BIM Based Approach for Structural Health Monitoring of Bridges. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2022, 26, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weile, W.; Chao, W.; Yongcheol, L. BIM-Based Construction Noise Hazard Prediction and Visualization for Occupational Safety and Health Awareness Improvement. Comput. Civ. Eng. 2017 2017, 262–269. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.; Cho, Y.; Zhang, S. Integrating Work Sequences and Temporary Structures into Safety Planning: Automated Scaffolding-Related Safety Hazard Identification and Prevention in BIM. Autom. Constr. 2016, 70, 128–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, A.S. An Overview of Building Information Modeling (BIM) & Construction of 4D BIM Model. Int. J. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2021, 9, 3754–3758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 31. US Environmental Protection Agency Exposure Factors Handbook: 2011 Edition. U.S. Environ. Prot. Agency, 2011; EPA/600/R, 1–1466.

- 32. United States Environmental Protection Agency Wildlife Exposure Factors Handbook, Vol 1. EPA 600-R-93-187. Washington, DC, 1993; I, 572.

- Liao, W.-B.; Ju, K.; Zhou, Q.; Gao, Y.-M.; Pan, J. Forecasting PM2·5 Induced Lung Cancer Mortality and Morbidity at County-Level in China Using Satellite-Derived PM2·5 Data from 1998 to 2016: A Modelling Study. Lancet 2019, 394, S70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, C.E.; Jones, R.M.; Boelter, F.W. Factors Influencing Dust Exposure: Finishing Activities in Drywall Construction. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2011, 8, 324–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Low-HR,

Low-HR,  Medium-HR,

Medium-HR,  High-HR.

High-HR.