Submitted:

13 December 2023

Posted:

14 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

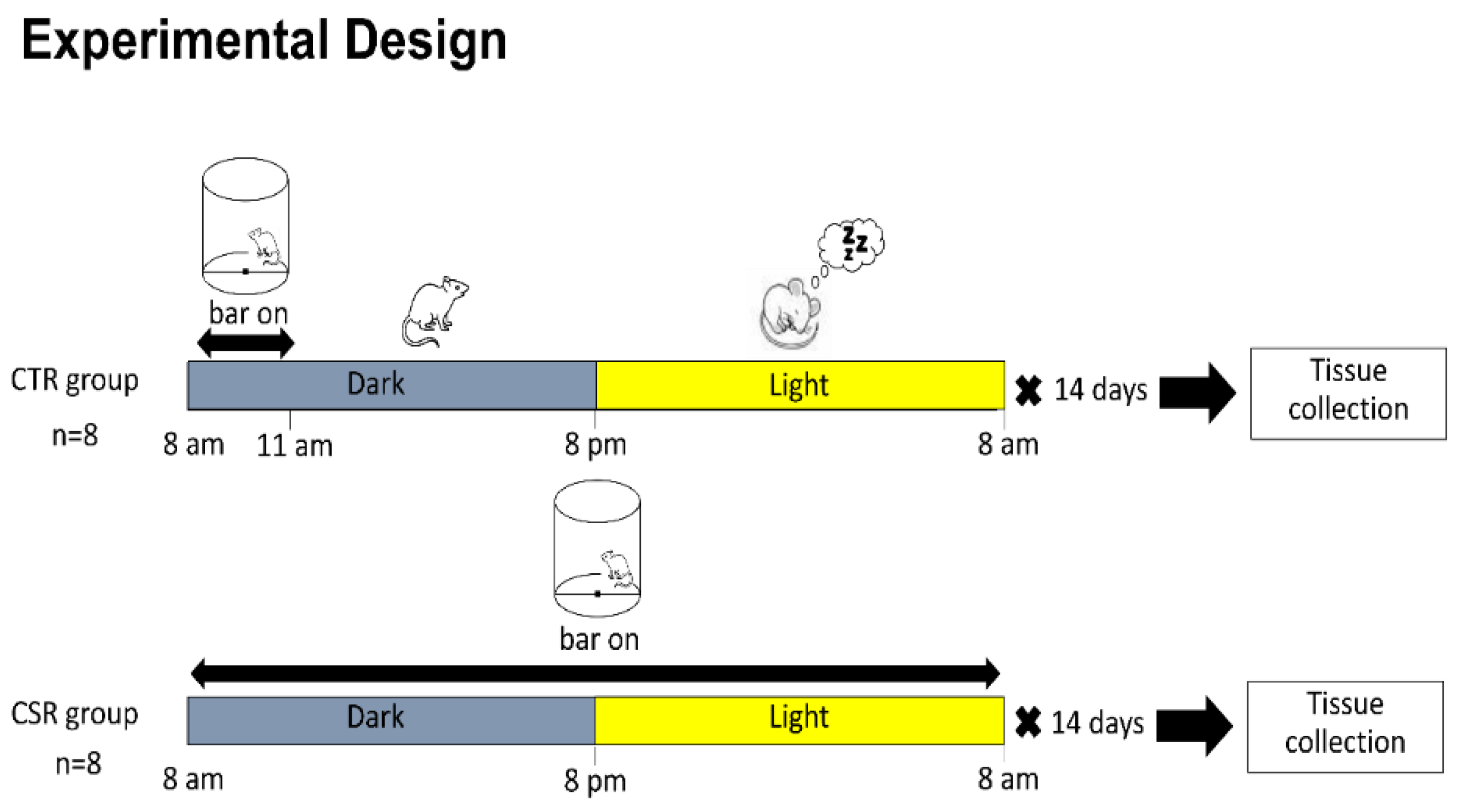

2.2. Experimental conditions

2.3. WAT Collection

2.4. Molecular Analyses

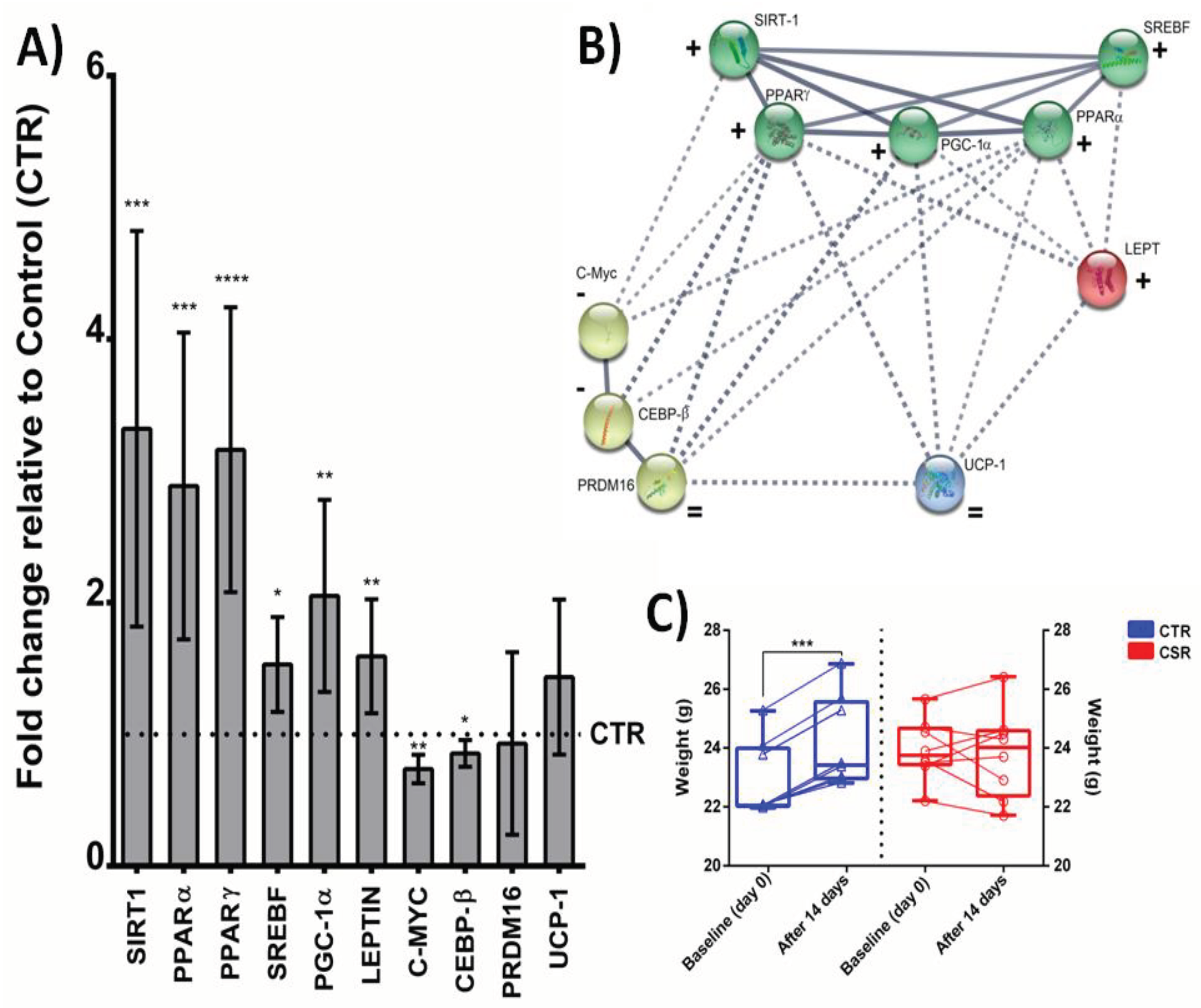

2.5. STRING network visualization

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maffei, M.; Halaas, J.; Ravussin, E.; Pratley, R.E.; Lee, G.H.; Zhang, Y.; Fei, H.; Kim, S.; Lallone, R.; Ranganathan, S. Leptin Levels in Human and Rodent: Measurement of Plasma Leptin and Ob RNA in Obese and Weight-Reduced Subjects. Nat. Med. 1995, 1, 1155–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scherer, P.E.; Williams, S.; Fogliano, M.; Baldini, G.; Lodish, H.F. A Novel Serum Protein Similar to C1q, Produced Exclusively in Adipocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 26746–26749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hotamisligil, G.S.; Arner, P.; Atkinson, R.L.; Spiegelman, B.M. Differential Regulation of the P80 Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptor in Human Obesity and Insulin Resistance. Diabetes 1997, 46, 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steppan, C.M.; Bailey, S.T.; Bhat, S.; Brown, E.J.; Banerjee, R.R.; Wright, C.M.; Patel, H.R.; Ahima, R.S.; Lazar, M.A. The Hormone Resistin Links Obesity to Diabetes. Nature 2001, 409, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, A.; Ezquerro, S.; Méndez-Giménez, L.; Becerril, S.; Frühbeck, G. Revisiting the Adipocyte: A Model for Integration of Cytokine Signaling in the Regulation of Energy Metabolism. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 309, E691–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuryłowicz, A.; Puzianowska-Kuźnicka, M. Induction of Adipose Tissue Browning as a Strategy to Combat Obesity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boutant, M.; Cantó, C. SIRT1 Metabolic Actions: Integrating Recent Advances from Mouse Models. Mol. Metab. 2014, 3, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seale, P.; Kajimura, S.; Yang, W.; Chin, S.; Rohas, L.M.; Uldry, M.; Tavernier, G.; Langin, D.; Spiegelman, B.M. Transcriptional Control of Brown Fat Determination by PRDM16. Cell Metab. 2007, 6, 38–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Breyer, M.D. The Role of PPARs in the Transcriptional Control of Cellular Processes. Drug News Perspect. 2002, 15, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majeed, Y.; Halabi, N.; Madani, A.Y.; Engelke, R.; Bhagwat, A.M.; Abdesselem, H.; Agha, M.V.; Vakayil, M.; Courjaret, R.; Goswami, N.; et al. SIRT1 Promotes Lipid Metabolism and Mitochondrial Biogenesis in Adipocytes and Coordinates Adipogenesis by Targeting Key Enzymatic Pathways. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 8177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smorlesi, A.; Frontini, A.; Giordano, A.; Cinti, S. The Adipose Organ: White-Brown Adipocyte Plasticity and Metabolic Inflammation: Adipocyte Plasticity and Adipose Organ. Obes. Rev. 2012, 13 Suppl 2, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Li, H.; Jin, X.; Zhang, Y.; Kang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, M.; Qian, Z.; Ma, Z.; Gao, X.; et al. Adipose-Specific Knockdown of Sirt1 Results in Obesity and Insulin Resistance by Promoting Exosomes Release. Cell Cycle 2019, 18, 2067–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalkiadaki, A.; Guarente, L. High-Fat Diet Triggers Inflammation-Induced Cleavage of SIRT1 in Adipose Tissue to Promote Metabolic Dysfunction. Cell Metab. 2012, 16, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshizaki, T.; Milne, J.C.; Imamura, T.; Schenk, S.; Sonoda, N.; Babendure, J.L.; Lu, J.-C.; Smith, J.J.; Jirousek, M.R.; Olefsky, J.M. SIRT1 Exerts Anti-Inflammatory Effects and Improves Insulin Sensitivity in Adipocytes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2009, 29, 1363–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cappuccio, F.P.; Taggart, F.M.; Kandala, N.-B.; Currie, A.; Peile, E.; Stranges, S.; Miller, M.A. Meta-Analysis of Short Sleep Duration and Obesity in Children and Adults. Sleep 2008, 31, 619–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, M.A.; Kruisbrink, M.; Wallace, J.; Ji, C.; Cappuccio, F.P. Sleep Duration and Incidence of Obesity in Infants, Children, and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. Sleep 2018, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Zhai, L.; Zhang, D. Sleep Duration and Obesity among Adults: A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. Sleep Med. 2014, 15, 1456–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spiegel, K.; Leproult, R.; L’hermite-Balériaux, M.; Copinschi, G.; Penev, P.D.; Van Cauter, E. Leptin Levels Are Dependent on Sleep Duration: Relationships with Sympathovagal Balance, Carbohydrate Regulation, Cortisol, and Thyrotropin. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004, 89, 5762–5771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spaeth, A.M.; Dinges, D.F.; Goel, N. Sex and Race Differences in Caloric Intake during Sleep Restriction in Healthy Adults. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 100, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, B.; Shi, C.; Park, C.G.; Zhao, X.; Reutrakul, S. Effects of Sleep Restriction on Metabolism-Related Parameters in Healthy Adults: A Comprehensive Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Sleep Med. Rev. 2019, 45, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, M.N.; Neylan, T.C.; Grunfeld, C.; Mulligan, K.; Schambelan, M.; Schwarz, J.-M. Subchronic Sleep Restriction Causes Tissue-Specific Insulin Resistance. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 100, 1664–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nedeltcheva, A.V.; Kessler, L.; Imperial, J.; Penev, P.D. Exposure to Recurrent Sleep Restriction in the Setting of High Caloric Intake and Physical Inactivity Results in Increased Insulin Resistance and Reduced Glucose Tolerance. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009, 94, 3242–3250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omisade, A.; Buxton, O.M.; Rusak, B. Impact of Acute Sleep Restriction on Cortisol and Leptin Levels in Young Women. Physiol. Behav. 2010, 99, 651–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guyon, A.; Morselli, L.L.; Balbo, M.L.; Tasali, E.; Leproult, R.; L’Hermite-Balériaux, M.; Van Cauter, E.; Spiegel, K. Effects of Insufficient Sleep on Pituitary-Adrenocortical Response to CRH Stimulation in Healthy Men. Sleep 2017, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itani, O.; Jike, M.; Watanabe, N.; Kaneita, Y. Short Sleep Duration and Health Outcomes: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Meta-Regression. Sleep Med. 2017, 32, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue, K.; Semba, E.; Yamakawa, T.; Terauchi, Y. Associations of Impaired Glucose Tolerance and Sleep Disorders with Mortality among the US General Population. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2021, 9, e002047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broussard, J.L.; Ehrmann, D.A.; Van Cauter, E.; Tasali, E.; Brady, M.J. Impaired Insulin Signaling in Human Adipocytes after Experimental Sleep Restriction: A Randomized, Crossover Study: A Randomized, Crossover Study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2012, 157, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuppli, C.A.; Fraser, D. The Interpretation and Application of the Three Rs by Animal Ethics Committee Members. Altern. Lab. Anim. 2005, 33, 487–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenzl, T.; Romanowski, C.P.N.; Flachskamm, C.; Honsberg, K.; Boll, E.; Hoehne, A.; Kimura, M. Fully Automated Sleep Deprivation in Mice as a Tool in Sleep Research. J. Neurosci. Methods 2007, 166, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergmann, B.M.; Kushida, C.A.; Everson, C.A.; Gilliland, M.A.; Obermeyer, W.; Rechtschaffen, A. Sleep Deprivation in the Rat: II. Methodology. Sleep 1989, 12, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbu, A.; Hedlund, G.P.; Lind, J.; Carlsson, C. Pref-1 and Adipokine Expression in Adipose Tissues of GK and Zucker Rats. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2009, 299, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandard, S.; Zandbergen, F.; Tan, N.S.; Escher, P.; Patsouris, D.; Koenig, W.; Kleemann, R.; Bakker, A.; Veenman, F.; Wahli, W.; et al. The Direct Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Target Fasting-Induced Adipose Factor (FIAF/PGAR/ANGPTL4) Is Present in Blood Plasma as a Truncated Protein That Is Increased by Fenofibrate Treatment. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 34411–34420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, L.; Qu, D.; Zhang, Q.; Jiang, J.; Zhou, H.; Jiang, R.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, H. Corrigendum: Phytosterol Esters Attenuate Hepatic Steatosis in Rats with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Rats Fed a High-Fat Diet. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 46884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nøhr, M.; Bobba, N.; Richelsen, B.; Lund, S.; Pedersen, S. Inflammation Downregulates UCP1 Expression in Brown Adipocytes Potentially via SIRT1 and DBC1 Interaction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volat, F.E.; Pointud, J.-C.; Pastel, E.; Morio, B.; Sion, B.; Hamard, G.; Guichardant, M.; Colas, R.; Lefrançois-Martinez, A.-M.; Martinez, A. Depressed Levels of Prostaglandin F2α in Mice Lacking Akr1b7 Increase Basal Adiposity and Predispose to Diet-Induced Obesity. Diabetes 2012, 61, 2796–2806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuda, T.; Kido, Y.; Asahara, S.-I.; Kaisho, T.; Tanaka, T.; Hashimoto, N.; Shigeyama, Y.; Takeda, A.; Inoue, T.; Shibutani, Y.; et al. Ablation of C/EBPbeta Alleviates ER Stress and Pancreatic Beta Cell Failure through the GRP78 Chaperone in Mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2010, 120, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciribilli, Y.; Borlak, J. Correction: Oncogenomics of c-Myc Transgenic Mice Reveal Novel Regulators of Extracellular Signaling, Angiogenesis and Invasion with Clinical Significance for Human Lung Adenocarcinoma. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 37269–37269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Q.; Jia, Y.; Yang, G.; Zhang, X.; Boddu, P.C.; Petersen, B.; Narsingam, S.; Zhu, Y.-J.; Thimmapaya, B.; Kanwar, Y.S.; et al. PPARα-Deficient Ob/Ob Obese Mice Become More Obese and Manifest Severe Hepatic Steatosis Due to Decreased Fatty Acid Oxidation. Am. J. Pathol. 2015, 185, 1396–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poswar, F. de O.; Farias, L.C.; Fraga, C.A. de C.; Bambirra, W., Jr; Brito-Júnior, M.; Sousa-Neto, M.D.; Santos, S.H.S.; de Paula, A.M.B.; D’Angelo, M.F.S.V.; Guimarães, A.L.S. Bioinformatics, Interaction Network Analysis, and Neural Networks to Characterize Gene Expression of Radicular Cyst and Periapical Granuloma. J. Endod. 2015, 41, 877–883. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Samal, S.K.; Routray, S.; Dash, R.; Dixit, A. Publisher Correction: Identification of Oral Cancer Related Candidate Genes by Integrating Protein-Protein Interactions, Gene Ontology, Pathway Analysis and Immunohistochemistry. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- STRING: Functional Protein Association Networks. Available online: http://string.embl.de (accessed on 21 November 2023).

- Korbel, J.O.; Jensen, L.J.; von Mering, C.; Bork, P. Analysis of Genomic Context: Prediction of Functional Associations from Conserved Bidirectionally Transcribed Gene Pairs. Nat. Biotechnol. 2004, 22, 911–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doncheva, N.T.; Morris, J.H.; Gorodkin, J.; Jensen, L.J. Cytoscape StringApp: Network Analysis and Visualization of Proteomics Data. bioRxiv 2018. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monsalve, F.A.; Pyarasani, R.D.; Delgado-Lopez, F.; Moore-Carrasco, R. Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Targets for the Treatment of Metabolic Diseases. Mediators Inflamm. 2013, 2013, 549627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Planavila, A.; Iglesias, R.; Giralt, M.; Villarroya, F. Sirt1 Acts in Association with PPARα to Protect the Heart from Hypertrophy, Metabolic Dysregulation, and Inflammation. Cardiovasc. Res. 2011, 90, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purushotham, A.; Schug, T.T.; Xu, Q.; Surapureddi, S.; Guo, X.; Li, X. Hepatocyte-Specific Deletion of SIRT1 Alters Fatty Acid Metabolism and Results in Hepatic Steatosis and Inflammation. Cell Metab. 2009, 9, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.B.; Spiegelman, B.M. ADD1/SREBP1 Promotes Adipocyte Differentiation and Gene Expression Linked to Fatty Acid Metabolism. Genes Dev. 1996, 10, 1096–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.B.; Wright, H.M.; Wright, M.; Spiegelman, B.M. ADD1/SREBP1 Activates PPARgamma through the Production of Endogenous Ligand. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998, 95, 4333–4337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picard, F.; Kurtev, M.; Chung, N.; Topark-Ngarm, A.; Senawong, T.; Machado De Oliveira, R.; Leid, M.; McBurney, M.W.; Guarente, L. Sirt1 Promotes Fat Mobilization in White Adipocytes by Repressing PPAR-Gamma. Nature 2004, 429, 771–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiang, L.; Wang, L.; Kon, N.; Zhao, W.; Lee, S.; Zhang, Y.; Rosenbaum, M.; Zhao, Y.; Gu, W.; Farmer, S.R.; et al. Brown Remodeling of White Adipose Tissue by SirT1-Dependent Deacetylation of Pparγ. Cell 2012, 150, 620–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koban, M.; Swinson, K.L. Chronic REM-Sleep Deprivation of Rats Elevates Metabolic Rate and Increases UCP1 Gene Expression in Brown Adipose Tissue. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005, 289, E68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cirelli, C.; Tononi, G. Uncoupling Proteins and Sleep Deprivation. Arch. Ital. Biol. 2004, 142, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yamauchi, T.; Waki, H.; Kamon, J.; Murakami, K.; Motojima, K.; Komeda, K.; Miki, H.; Kubota, N.; Terauchi, Y.; Tsuchida, A.; et al. Inhibition of RXR and PPARγ Ameliorates Diet-Induced Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes. J. Clin. Invest. 2001, 108, 1001–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taheri, S.; Lin, L.; Austin, D.; Young, T.; Mignot, E. Short Sleep Duration Is Associated with Reduced Leptin, Elevated Ghrelin, and Increased Body Mass Index. PLoS Med. 2004, 1, e62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaput, J.-P.; Després, J.-P.; Bouchard, C.; Tremblay, A. Short Sleep Duration Is Associated with Reduced Leptin Levels and Increased Adiposity: Results from the Québec Family Study. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007, 15, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stern, J.H.; Grant, A.S.; Thomson, C.A.; Tinker, L.; Hale, L.; Brennan, K.M.; Woods, N.F.; Chen, Z. Short Sleep Duration Is Associated with Decreased Serum Leptin, Increased Energy Intake and Decreased Diet Quality in Postmenopausal Women. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2014, 22, E55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, A.C.; Dorrian, J.; Liu, P.Y.; Van Dongen, H.P.A.; Wittert, G.A.; Harmer, L.J.; Banks, S. Impact of Five Nights of Sleep Restriction on Glucose Metabolism, Leptin and Testosterone in Young Adult Men. PLoS One 2012, 7, e41218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, N.S.; Banks, S.; Dinges, D.F. Sleep Restriction Is Associated with Increased Morning Plasma Leptin Concentrations, Especially in Women. Biol. Res. Nurs. 2010, 12, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.L.; Xu, F.; Babineau, D.; Patel, S.R. Sleep Duration and Circulating Adipokine Levels. Sleep 2011, 34, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pejovic, S.; Vgontzas, A.N.; Basta, M.; Tsaoussoglou, M.; Zoumakis, E.; Vgontzas, A.; Bixler, E.O.; Chrousos, G.P. Leptin and Hunger Levels in Young Healthy Adults after One Night of Sleep Loss: Leptin after One Night of Sleep Loss. J. Sleep Res. 2010, 19, 552–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lefterova, M.I.; Zhang, Y.; Steger, D.J.; Schupp, M.; Schug, J.; Cristancho, A.; Feng, D.; Zhuo, D.; Stoeckert, C.J., Jr; Liu, X.S.; et al. PPARgamma and C/EBP Factors Orchestrate Adipocyte Biology via Adjacent Binding on a Genome-Wide Scale. Genes Dev. 2008, 22, 2941–2952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, L.; Li, X.; Tang, Q.-Q. Transcriptional Regulation of Adipocyte Differentiation: A Central Role for CCAAT/Enhancer-Binding Protein (C/EBP) β. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 755–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siersbæk, R.; Nielsen, R.; Mandrup, S. Transcriptional Networks and Chromatin Remodeling Controlling Adipogenesis. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 23, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceseña, T.I.; Cardinaux, J.-R.; Kwok, R.; Schwartz, J. CCAAT/Enhancer-Binding Protein (C/EBP) Beta Is Acetylated at Multiple Lysines: Acetylation of C/EBPbeta at Lysine 39 Modulates Its Ability to Activate Transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 956–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdesselem, H.; Madani, A.; Hani, A.; Al-Noubi, M.; Goswami, N.; Ben Hamidane, H.; Billing, A.M.; Pasquier, J.; Bonkowski, M.S.; Halabi, N.; et al. SIRT1 Limits Adipocyte Hyperplasia through C-Myc Inhibition. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 2119–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- B Tóth, B.; Barta, Z.; Barta, Á.B.; Fésüs, L. Regulatory Modules of Human Thermogenic Adipocytes: Functional Genomics of Large Cohort and Meta-Analysis Derived Marker-Genes. BMC Genomics 2021, 22, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rechtschaffen, A.; Gilliland, M.A.; Bergmann, B.M.; Winter, J.B. Physiological Correlates of Prolonged Sleep Deprivation in Rats. Science 1983, 221, 182–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rechtschaffen, A.; Bergmann, B.M. Sleep Deprivation in the Rat: An Update of the 1989 Paper. Sleep 2002, 25, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Everson, C.A.; Crowley, W.R. Reductions in Circulating Anabolic Hormones Induced by Sustained Sleep Deprivation in Rats. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004, 286, E1060–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Everson, C.A.; Toth, L.A. Systemic Bacterial Invasion Induced by Sleep Deprivation. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2000, 278, R905–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barf, R.P.; Van Dijk, G.; Scheurink, A.J.W.; Hoffmann, K.; Novati, A.; Hulshof, H.J.; Fuchs, E.; Meerlo, P. Metabolic Consequences of Chronic Sleep Restriction in Rats: Changes in Body Weight Regulation and Energy Expenditure. Physiol. Behav. 2012, 107, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baud, M.O.; Magistretti, P.J.; Petit, J.-M. Sustained Sleep Fragmentation Affects Brain Temperature, Food Intake and Glucose Tolerance in Mice: Sleep Fragmentation Induces Metabolic Impairments. J. Sleep Res. 2013, 22, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene | Primer sequence (5’- 3’) | GenBank | Reference |

| PPARγ | ATGGAGCCTAAGTTTGAGTTTGCT GGATGTCCTCGATGGGCTTCA |

XM_006505737.5 | [32] |

| PPARα | CACCCTCTCTCCAGCTTCCA GCCTTGTCCCCACATATTCG |

XM_011245516.4 | [33] |

| SIRT-1 | CGATGACAGAACGTCACACG TCGAGGATCGGTGCCAATCA | NM_019812.3 | [34] |

| LEPT | GACATTTCACACAGGCAGTCG GCAAGCTGGTGAGGATCTGT |

NM_008493.3 | [31] |

| SREBF | GAACAGACACTGGCCGAGAT GAGGCCAGAGAAGCAGAAGAG |

NM_011480.4 | [35] |

| CEBP-β | ACCGGGTTTCGGGACTTGA GTTGCGTAGTCCCGTGTCCA |

X62600.1 | [36] |

| C-Myc | GCCACGTCTCCACACATCAG TGGTGCATTTTCGGTTGTTG |

XM_021216459.1 | [37] |

| PRDM16 | CACGGTGAAGCCATTCATATGCG AGGTTGGAGAACTGCGTGTAGG |

XM_006539171.5 | [34] |

| UCP-1 | GCCATCTGCATGGGATCAAACC TCGTCCCTTTCCAAAGTGTTGAC |

NM_009463.3 | [34] |

| PGC-1α | CTCCAGCCTGACGGCACCC GCAGGGACGTCTTTGTGGCT |

NM_001330751.2 | [38] |

| G6PDH | ATTGACCACTACCTGGGCAA GAGATACACTTCAACACTTTGACCT |

XM_021153829.2 | [31] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).