1. Introduction

Globally, an estimated 810 women die every day from preventable causes related to pregnancy and childbirth; of these deaths, 94% of all maternal deaths occur in low-resource settings [

1]. Half of all neonatal and maternal deaths occur within the first 24 hours after birth, and 75% of all neonatal deaths occur within the seven days after delivery [

2]. Most of these maternal and newborn deaths occurring immediately after birth can be averted by providing appropriate and timely postnatal care [

3,

4,

5]. Studies in South Africa and Asia estimated that maternal deaths are extremely high within the intrapartum period and up to the first two days of childbirth [

6,

7]. Additionally, studies around the world suggest that improving coverage and quality during pre-partum and postpartum periods can reduce 54% of maternal deaths annually by 2025 [

8]. World Health Organization's (WHO) postnatal care guideline recommends that women must receive a postnatal check within the first 48 hours of childbirth, along with the recommended components [

9,

10].

Since 2000, Bangladesh has made remarkable progress in declining maternal mortality. However, this progress has stagnated as the maternal mortality ratio of 2010 and 2016 are almost identical (196 per 100,000 live births) [

11]. This stall in the decline of maternal mortality is alarming, as nearly 70% of these deaths occur during the postpartum period, accounting for nearly 135 deaths per 100,000 live births [

11]. The leading cause of all these maternal deaths are ante and postpartum haemorrhage (31%), followed by eclampsia (24%) [

11]. In Bangladesh, nearly 88% of women were found to have received antenatal care (A.N.C.) from a skilled provider at least once during pregnancy, and only 21% received quality care [

12,

13]. In comparison, the coverage of delivery by a skilled provider and postnatal care within two days after birth is lower—at 50% and 52%, respectively [

14,

15]. National surveys included quality of antenatal care; however, no data for Bangladesh is available that highlights the quality of postnatal care. The fourth Health Nutrition and Population Sector Program (H.N.P.S.P.) of Bangladesh recommended initiating postnatal care within 48 hours of birth [

16]. However, this focuses only on connecting mothers and newborns with the health system, with no suggestion on the quality of services received during that time. In spite of undertaking several quality of care initiative by Bangladesh Government, substandard quality continues to be a cause of a growing concern [

17].

Evidence indicated that increased recommended postnatal coverage alone does not reduce maternal morbidity and mortality [

8]. The introduction and implementation of quality care are critical in maternal and newborn care [

18,

19]. Baqui et al. (2009) showed that receiving the first postnatal visit on the day of birth in Bangladesh was associated with considerably lower neonatal mortality than receiving no visit after birth [

20]. Although several studies used secondary analysis to highlight factors influencing women's uptake of postnatal care, most of these studies ignored the components and quality of postnatal care. With the expansion of coverage, the ongoing concern over poor quality becomes more evident. Increasing coverage without quality leads to missed opportunities to improve outcomes, which results in unsafe or delayed procedures and treatments [

17]. Thus there is a dire need to explore further the gap between coverage and quality of services received by women that may influence postnatal care utilization within 48 hours of birth [

21,

22,

23,

24].

For this study, we have utilized data from national-level household surveys, the Bangladesh Maternal Mortality Surveys (B.M.M.S.), to study the changes in prevalence of coverage and content of postnatal care, and explored the determinants of quality postnatal care. To measure the quality, we have followed the World Health Organization's (WHO) standards of improving the quality of maternal and newborn care [

10]. However, even surveys as extensive as BMMS do not collect all components of quality postnatal care. As there is a scarcity of evidence addressing determinants of quality postnatal care (qPNC) practices of mothers in the current country context, the objective of the proposed study is to examine and establish the gap between coverage and components – as a proxy for quality postnatal care and to assess the range of factors that affects the quality postnatal care utilization following childbirth by the medically trained provider among facility and home births in Bangladesh.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Data

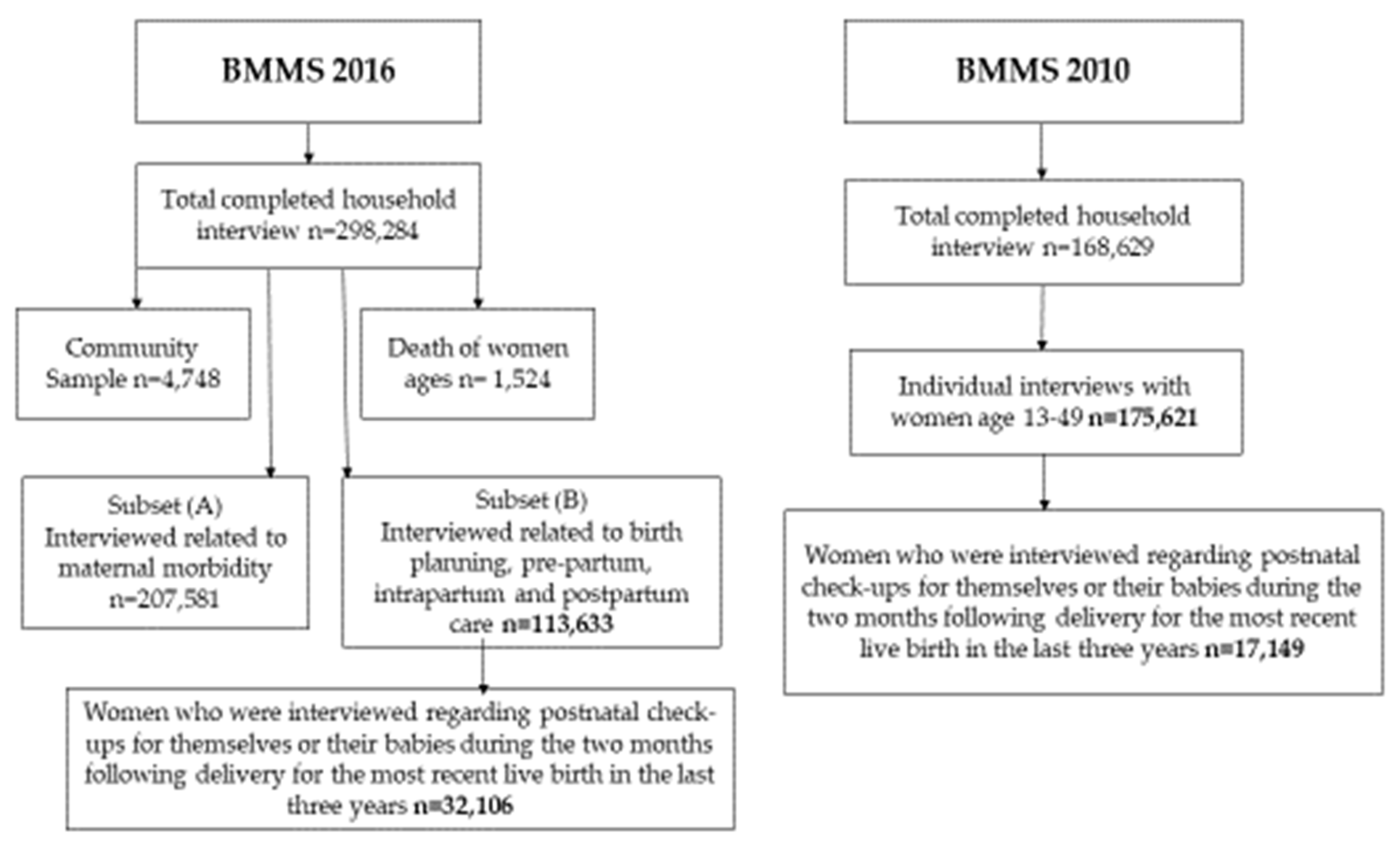

This study focused on the survey area in Bangladesh covered by the BMMS 2010 and 2016 [

11,

25] . The primary objective of these surveys was to collect data on maternal mortalities in Bangladesh. The required number of households to be surveyed was calculated using a multi-stage sample selection procedure, the details of which could be found elsewhere [

11]. Three types of regions were covered urban, rural, and other (peri-) urban areas. At the household level (household questionnaire), the questionnaires focused on household background characteristics and death information, and at the individual level (women's questionnaire), they focused on respondents' background, reproductively, child mortality, and family planning.

Additional questionnaires, such as the verbal autopsy and community questionnaires, collected information on causes of death for female adults preceding the survey, and the latter queried about the socioeconomic condition of the community and the availability and accessibility of health and family planning in the community [

11].

2.2. Study Design and Settings

Since the primary outcome of interest of our study was PNC and its components for the most recent live birth, we limited the sample to women who were asked if they received postnatal checkups for themselves or their babies during the two months following delivery for the most recent live birth in the three years before the BMMS 2016 survey. For comparisons and descriptive analysis, we have used BMMS 2010 and for determinants analysis we have used BMMS 2016. We have applied similar selection criteria for the BMMS 2010 survey data as of BMMS 2016. Therefore, the total sample size for BMMS 2010 was 17,149 and for BMMS 2016 was 32,106 mothers (

Figure 1).

2.3. Outcome variable

To define qPNC, we used WHO recommendations on postnatal care of the mother and newborn [

9]. A postnatal care was considered a 'qPNC', if it had covered the followings at least once during the postnatal period:

At least one PNC within 48 hours by a medically trained provider, who could be a doctor, nurse/midwife/paramedic/Family Welfare Visitor (FWV), Community Skill Birth Attendance (CSBA), and Sub Assistant Community Medical Officer (SACMO)

Breast Examination

Counsel on postpartum danger signs

Temperature check

Checked for Vaginal discharge (excessive bleeding and foul smelling discharge)

2.4. Key Independent variables

Key independent variables described below were chosen based on previous literature reviews.

- 2.4.1.

Background characteristics: Mother's age at birth (<20, 20-34, and 35-49, education (no education, primary, and secondary or above), religion (Muslim and others), household wealth (poor, middle-class, and rich), birth order (1, 2, and 3 or more) and ownership of mobile phone (yes or no) were analyzed as categorical variables. Due to their low numbers, all religious status other than Muslim were combined into one category and labeled "others".

- 2.4.2.

-

Maternal health services: In terms of maternal health services, the following indicators were considered;

ANC from Medically Trained Provider (MTP)- No ANC, ANC from qualified (which includes doctors, Nurses/midwives/paramedics/FWV, CSBA, MA/SACMO), and unqualified providers

Number of ANC - No ANC, 1-3 ANC, and 4 or more ANC

Place of delivery- Home and facility births

Type of birth attendant - Skilled and unskilled. Skilled providers include qualified doctors, nurses/midwives/paramedics/ FWV, CSBA, and MA/SACMO

Mode of delivery - Normal or C-section

Complications during pregnancy – Yes or No

Complications during delivery - Yes or No

Complications during the postnatal period - Yes or No

Savings available for delivery care - Yes or No

Mobile phone ownership - Yes or No

2.5. Statistical analysis

Weighted descriptive statistics and chi-square analyses were carried out on all predictor and demographic variables from the BMMS 2016 survey to compare PNC provided by qualified healthcare providers within 48 hours of home and health facilities delivery. Additionally, from BMMS 2010 and BMMS 2016, descriptive statistics were calculated for the components of PNC. For creating the categories of household wealth, we used the data on ownership of household items. We used the data on household possessions; floor construction materials, wall, and roof; drinking water source; toilet facilities; and ownership of land and domestic animals. Through principal components analysis, each asset was assigned a weight (factor score). After summing each household score, individuals were ranked into three wealth categories (poor, middle-class, and rich) according to the total score of the household where they live.

Log-linear regression models predicting the receipt of qPNC outcomes among home and facility deliveries were developed, using predicting factors such as mother's education, wealth index, number of ANC, ANC from MTP, type of birth attendant, complication during pregnancy, complication during delivery, complication during postnatal period, saving for delivery care. In log-linear regression models predicting the receipt of qPNC outcomes among facility births, we added type of facility births, and the mode of delivery with the mentioned variables, as these variables were not relevant for home births. Stata 14.2 was used to analyze the data. Since we utilized a multi-stage cluster sampling methodology, all estimates were produced following the requisite weighting. Statistically significant associations were determined based on p-value < 0.05.

2.6. Ethics

The study utilized publicly accessible secondary data provided by Measure Evaluation and the Bangladesh Maternal Mortality Survey (BMMS). No ethical approval was necessary for the use of this secondary data as it falls under the category of publicly available datasets, and the data usage complies with the guidelines provided by the data source. Comprehensive details regarding the data collection methods used by EDHS are documented in published reports [

11,

25].

3. Results

3.1. Background Characteristics of study population

The study included a total weighted sample of 32,106 reproductive aged mothers from all eight division of Bangladesh. Of the women in our sample, majority (78%) were aged between 20 and 34, 91% had access to a mobile phone, 61% completed secondary education or higher, and 42% belonged to a poor household. Only 38% women received 4 or more ANC and half (50%) of the mothers were delivered by skill birth attendants.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics BMMS 2016 (n = 32,106).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics BMMS 2016 (n = 32,106).

| Characteristic |

n |

% |

| Mother's age at birth |

|

|

| <20 |

5,094 |

15.9 |

| 20-34 |

24,894 |

77.5 |

| 35-49 |

2,118 |

6.6 |

| Mobile phone |

|

|

| Yes |

29,239 |

91.1 |

| No |

2,867 |

8.9 |

| Mother's education |

|

|

| No education |

3,145 |

9.8 |

| Primary |

9,487 |

29.6 |

| Secondary+ |

19,474 |

60.7 |

| Religion |

|

|

| Muslim |

29,517 |

91.9 |

| Others |

2,589 |

8.1 |

| Wealth index |

|

|

| Poor |

13,344 |

41.6 |

| Middle-class |

6,287 |

19.6 |

| Rich |

12,475 |

38.9 |

| Birth Order |

|

|

| 1 |

13,358 |

41.6 |

| 2 |

11,067 |

34.5 |

| 3+ |

7,681 |

23.9 |

| Number of ANC |

|

|

| No ANC |

5,602 |

17.5 |

| 1-3 |

14,292 |

44.5 |

| 4+ |

12,212 |

38.0 |

| ANC from MTP |

|

|

| No ANC |

5,608 |

17.5 |

| Qualified Provider |

23,581 |

73.5 |

| Unqualified Provider |

2,917 |

9.1 |

| Type of facility of delivery |

|

|

| Private facility |

10,341 |

67.7 |

| Public facility |

4,936 |

32.3 |

| Type of birth attendant |

|

|

| Skilled |

16,176 |

50.4 |

| Unskilled |

15,930 |

49.6 |

| Complications during pregnancy |

|

|

| Yes |

20,379 |

63.5 |

| No |

11,727 |

36.5 |

| Complications during delivery |

|

|

| Yes |

24,179 |

75.3 |

| No |

7,927 |

24.7 |

| Complications during Postnatal Period |

|

|

| Yes |

25,684 |

80.0 |

| No |

6,422 |

20.0 |

| Savings available for delivery care |

|

|

| Yes |

14,894 |

46.4 |

| No |

17,212 |

53.6 |

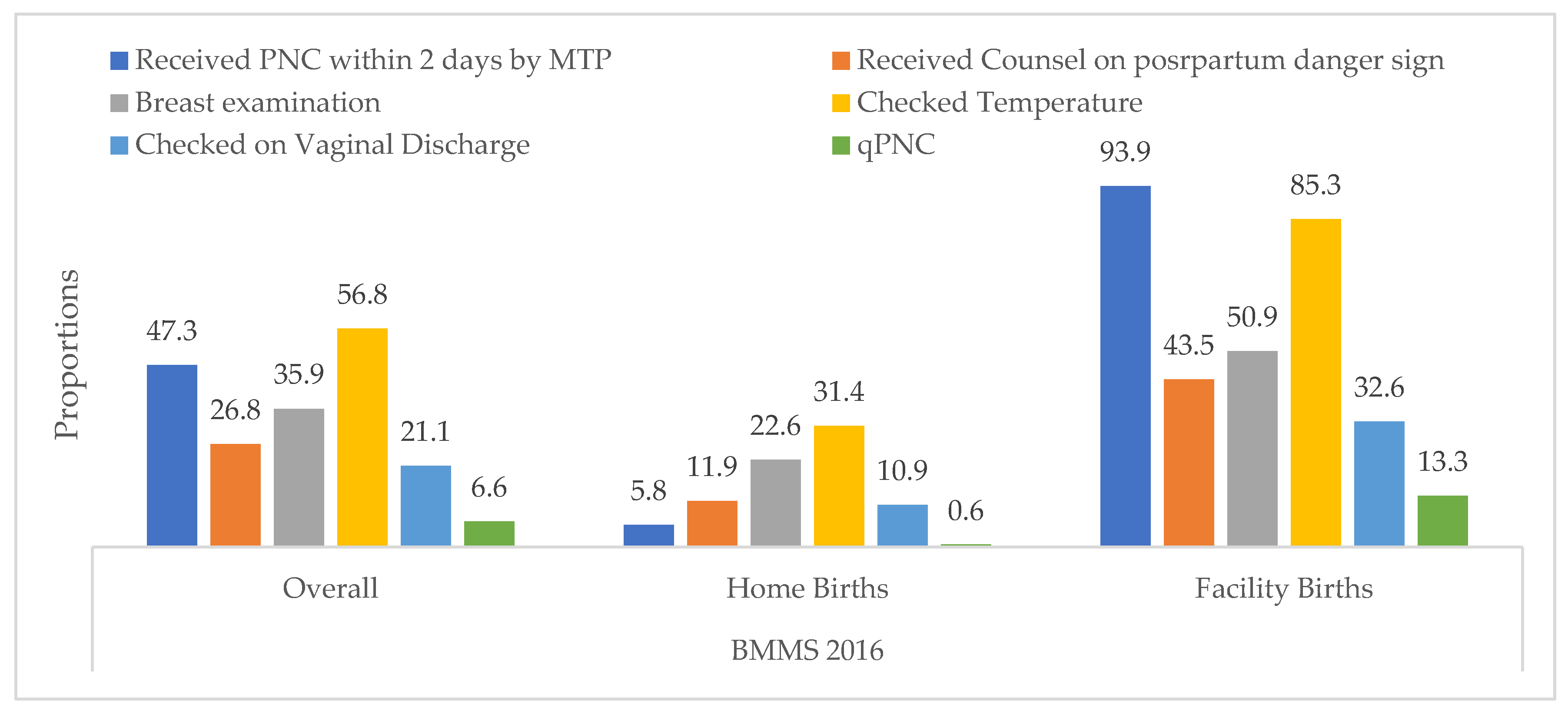

3.1. Components of PNC

There was a significant difference in the prevalence of components among home and facility births. Overall, the prevalence of qPNC was very low just 6.57%. The prevalence of qPNC among home and facility births was 0.6% and 13.3% respectively. Only 5.8% women who were delivered

Figure 2.

Prevalence of PNC components during BMMS 2016.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of PNC components during BMMS 2016.

In 2016, 44.6% of women who had home deliveries and 95.9% of women having facility deliveries had received postnatal visit within 42 days of the delivery. In contrast, only 0.57% and 13.3% of women had received qPNC for home and facility births, respectively. Between 2010 to 2016, there was an increase in receiving a postnatal visit within 48 hours and receiving this visit from a qualified provider. Additionally, the highest percentage of increase from 2010 to 2016 was observed for receiving a PNC within 48 hours (34%), followed by receiving a PNC within 42 days (28%), and receiving a PNC visit by a qualified provider within 48 hours (24%).

Table 2.

Prevalence of postnatal care-related indicators among home and facility births.

Table 2.

Prevalence of postnatal care-related indicators among home and facility births.

| |

2010 |

2016 |

| Indicators |

Home births |

Facility births |

Total |

Home births |

Facility births |

Total |

| % |

|---|

| Received postnatal visit within 42 days |

- |

- |

41.0 |

44.6 |

95.9 |

69.0 |

| Received postnatal visit within 48 hours |

16.6 |

80.1 |

32.0 |

39.7 |

94.9 |

66.0 |

| Postnatal visit by a qualified provider within 2 days |

4.6 |

78.8 |

23.0 |

5.8 |

93.9 |

47.0 |

| qPNC |

- |

- |

|

0.6 |

13.3 |

7.2 |

3.4. Utilization and factors associated with qPNC in Bangladesh

Table 3 reports the prevalence and factors associated with qPNC among home and facility births. The table suggests that having skilled birth attendants was a strong precursor of qPNC for both facility (13.6%) and home deliveries (6.3%). Similarly,

Table 2 demonstrates that the percentages of women receiving qPNC after facility births and reporting no complications during delivery (15.3%) and postnatal period (15.5%) were higher compared to women who received qPNC after home births (1.2% and 1.4%, respectively).

3.4. Determinants of qPNC in Bangladesh

Logistic regression analysis for mothers who had home births, we find that compared to a poor household, a mother from a rich household is 2.03 times (aRR: 2.03, 95% CI [1.26, 3.28]) more likely to get quality postnatal care. Mothers with a complication during a delivery period are 1.21 times more likely (aRR: 1.21, 95% CI [1.11, 1.33]) to get quality postnatal care. In contrast, no significant association was found for mothers' age at birth, education, number of ANC, ANC from MTP, saving money for delivery care, and having a mobile phone.

Furthermore,

Table 4 also illustrates determinants of qPNC of mothers who had facility births. Mothers whose age at birth was 20 to 34 years had 17% more odds (aRR: 1.17, 95%CI [1.04-1.32]) of receiving qPNC than mothers whose age at birth was less than 20 years old. Compared to mothers with unskilled birth attendants, mothers with skilled birth attendants are 7.90 times more likely (aRR: 7.90, 95% CI [1.98 – 31.41]) to receive qPNC. Additionally, compared to normal delivery, mothers who had c-sections are 1.58 times more likely (aRR: 1.58, 95% CI [1.42 - 1.76]) to get quality postnatal care. Moreover, complications during delivery and savings available for delivery care are significantly associated (aRR: 1.21, 95% CI [1.10 - 1.33] and aRR: 1.20, 95% CI [1.1 - 1.31]) with receiving qPNC. On the other hand, no significant associations were found for the mother's age at birth, mother's education, wealth index, number of ANC, ANC from MTP, type of facility births, complications during the postnatal period, and owning a mobile phone.

4. Discussion

This study used national-level cross-sectional surveys to identify the determinants of qPNC among home and facility births in the context of Bangladesh. The study considered the essential components of qPNC and their associated factors that may influence women to receive qPNC. One of the primary findings was the gap between coverage and quality of postnatal care. Considering quality postnatal care, the majority of the women did not receive quality care. A similar study in Myanmar also highlighted that, although women in facility birth had adequate contacts through qualified providers, however, women who gave birth at home had a very low prevalence of postnatal contact by qualified providers within 48 hours after birth [

26]. Results from our study would supplement the existing evidence by identifying potential gaps and opportunities for improving quality postnatal care practices in rural Bangladesh.

Among home births socio-demographic factors and complications during the postnatal period highly influenced qPNC, and for facility births, age, mode of delivery, complications during delivery and savings available for delivery care were significantly associated with quality care. The type of provider was also found to be significantly associated with quality postnatal care. The two survey data reported the accelerating trend of postnatal checkups for mothers within 48 hours of delivery by a qualified provider, which increased from 23% in 2010 to 47% in 2016. However, the prevalence of qPNC was rather low only 6.6% in 2016. This gap between contact and quality is really alarming.

Several studies have indicated that increased recommended postnatal coverage alone does not reduce maternal morbidity and mortality [

8]. The introduction and implementation of quality of care is recognized as critical aspect in maternal and newborn care [

18,

19]. Our findings highlighted that in spite of that, the quality of postnatal care remains as low as 1% for home birth and 13% for facility births. Focusing on the distribution of PNC components revealed the full spectrum of quality of postnatal care. For example, only half of the women had their temperature checked (57%). Similarly, more focus should be given to providing counselling on postpartum maternal and newborn danger signs (27%) and examining vaginal discharge (21%) after delivery. Mothers' knowledge of danger signs can help identify early maternal and newborn complications. Components of postnatal care for home delivered women were low across all spectrum.

Both coverage and quality of postnatal care for home births were found to be strikingly low. Previous studies highlighted the importance of early initiation of PNC, which is, receiving PNC within 48 hours of birth [

27]. Only 5.8% of women received postnatal care from a medically trained provider within two days. There might be cultural and religious attributes to lower postnatal care. The socio-cultural beliefs in the country hinder women to receive healthcare services from a male doctors or unknown health care providers in healthcare facilities [

28]. Similar studies in the country highlighted that women from Muslim households need permission from their husbands to go to health facilities [

29]. All these barriers point towards implementing policies to deliver postnatal care for home births to avert maternal and neonatal morbidity. Although we did not find any such association between religion and qPNC.

Wealth was considered to be an important factor for receiving quality care for a home birth as the cost of care acts as a barrier and hinders access to health care [

30]. Our study portrays that mothers who belong to higher social classes were 1.95 times more likely to receive quality postnatal care compared to poor households. Previous studies also showed that mothers who belong to a higher social class were more likely to seek qPNC during maternal complications [

28,

31]. Antenatal care is considered the entry point of maternal and newborn care, suggesting that it is time to inform mothers about maternal danger signs, possible postpartum complications, and the benefits of qPNC practices [

32,

33,

34]. Studies in India and Cambodia found that women receiving high-quality antenatal care were better informed about pregnancy during ANC visits, were more likely to be delivered by skilled birth attendants, and continued receiving postnatal care after childbirth [

35,

36]. Our findings failed to find such an association.

Women with complications during the postnatal period were 2.48 times more likely to receive quality postnatal care. This finding suggests that mothers only seek care when they face any complications. Hence routine postnatal care practice often gets ignored. A study in Pakistan also demonstrates that mothers visit health facilities during postnatal periods for serious and fatal complications only [

37]. Due to a lack of routine postpartum care for home births, women are undiagnosed of severe postpartum complications, leading to serious health risks. Despite having a home visitation program by the Government of Bangladesh, postnatal care remains low. Therefore, policies should concentrate more on ensuring home visits at the community level and improving high-qPNC packages for reaching women.

Place of delivery has always played a vital role in obtaining maternal postnatal services [

38]. In our study, 94% of women who had facility births received PNC within 48 hours of birth. Among them, older women had higher use of qPNC. Age is often used as a proxy for mothers' accumulated knowledge of healthcare services, which may guide them to access healthcare services [

21]. Another possible reason could be that older women are more prone to develop pregnancy and intrapartum complications, increasing their use of postnatal care.

Women having a cesarean delivery and experiencing complications during delivery had a positive association with receiving postnatal care. Both these factors imply that these women were at high risk of developing postpartum complications hence, increased chance of postnatal care [

39,

40]. One possible reason for low qPNC at the facility level in Bangladesh might be due to mothers' short length of stay at the hospital, especially for vaginal deliveries, which are stays less than 48 hours [

41]. However, data on the length of stays were missing, which needs to be added in future surveys to get the true pictures of missing PNC cases. Our findings suggested that women who reported saving money during delivery care were 1.20 times more likely to obtain quality care. Mothers who received delivery by skilled birth attendants were more likely to have received quality postnatal care for both facility and home births. Studies in 30 lower-middle-income nations had also reported such associations [

41,

42]. Facility survey data should be linked with population-level survey data to know the quality of available services [

8].

There are some limitations of this study. A cross-sectional survey was used to gather the data for this study's outcomes; as a result, we were unable to draw a connection between the explanatory factors and relevant PNC-related outcomes of interest. Additionally, the survey collected retrospective data based on the information provided by the respondent, which may be subjected to recall bias. Other important components to measure quality postnatal care, like blood pressure measurement and anemia, were not collected in this survey.

5. Conclusions

Ensuring recommended postnatal care has the potential to save maternal and newborn lives. Our study indicated an alarming difference between coverage and components of the quality of postnatal care. Therefore, this is the time when our policies need to focus on components of quality postnatal care. National surveys should include all the different spectrums of quality of postnatal care accordingly to WHO qPNC guidelines to better understand the complete scenario of quality postnatal care. Need-based solutions need to be considered as well when planning for interventions, which should also determine health resource allocations in the country. In addition, implementing awareness programs on postnatal care and counselling on postnatal care benefits should be strengthened to return women to facilities. Almost half of the deliveries were home-based, which also indicates the need for home visits offering qPNC. As Government of Bangladesh is heavily investing in community interventions, these interventions should also focus on raising awareness of the importance of postpartum care. The existing system should ensure all the services are readily available and rightly provided to mothers and their newborns.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and design of study: S.S.P.; Methodology, S.S.P and N.B.A.; Data analysis, S.S.P., D.P.D and H.K.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S.P and D.P.D.; writing—review and editing, S.S.P, A.Y.M.A, N.B.A and S.M.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Data Availability Statement

The Bangladesh Maternal Mortality and Health Care Survey (BMMS) 2010 and 2016 datasets are publicly available at UNC Dataverse (

www.dataverse.unc.edu).

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT), Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID)/Bangladesh, the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development (DFID), MEASURE Evaluation and the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (icddr,b) for providing the data for the analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- WHO. Maternal Mortality. Fact Sheets 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/maternal-mortality (accessed on 17 February 2020).

- WHO. Newborns: Reducing Mortality. Fact Sheets 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/newborns-reducing-mortality (accessed on 17 February 2020).

- Darmstadt, G.L.; Choi, Y.; Arifeen, S.E.; Bari, S.; Rahman, S.M.; Mannan, I.; Seraji, H.R.; Winch, P.J.; Saha, S.K.; Ahmed, A.S.M.N.U.; et al. Evaluation of a cluster-randomized controlled trial of a package of community-based maternal and newborn interventions in Mirzapur, Bangladesh. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martines, J.; Paul, V.K.; A Bhutta, Z.; Koblinsky, M.; Soucat, A.; Walker, N.; Bahl, R.; Fogstad, H.; Costello, A. Neonatal survival: A call for action. Lancet 2005, 365, 1189–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sines, E.; et al. Postnatal care: A critical opportunity to save mothers and newborns. 2007: 1-7.

- Maswime, S.; Buchmann, E. Buchmann, and Obstetrics, Causes and avoidable factors in maternal death due to cesarean-related hemorrhage in South Africa. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2016, 134, 320–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, S.; et al. A prospective key informant surveillance system to measure maternal mortality–findings from indigenous populations in Jharkhand and Orissa, India. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2008, 8, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvajal–Aguirre, L.; et al. Gap between contact and content in maternal and newborn care: An analysis of data from 20 countries in sub–Saharan Africa. J. Glob. Health 2017, 7, 020501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organization, W.H. WHO recommendations on postnatal care of the mother and newborn. 2014: World Health Organization.

- Organization, W.H. Standards for improving quality of maternal and newborn care in health facilities. 2016.

- National Institute of Population Research and Training, I.C.f.D.D.R., Bangladesh, MEASURE Evaluation, USAID, Bangladesh Maternal Mortality and Health Care Survey BMMS, in Preliminary Report. 2016.

- National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT) and ICF, Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2017-18: Key Indicators. 2019: Dhaka, Bangladesh, and Rockville, Maryland, USA.

- National Institute of Population Research and Training, M.E.a.F.W.D., Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Dhaka, Bangladesh, The DHS Program, ICF, Rockville, Maryland, USA, Preliminary Reports/Key Indicators Reports.

- National Institute of Population Research and Training Medical Education and Family Welfare Division Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Dhaka, B., USAID, Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey, in Key Indicators. 2017–18.

- National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT) and ICF, Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey, in Key Indicators. 2017–18. 2019: Dhaka, Bangladesh, and Rockville, Maryland, USA.

- Ministry of Health & Family Welfare of Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, Maternal Health Standard Operating Procedures (SOP). Vol. 1. 2019.

- Health, M.o. and F. Welfare, National strategy for maternal health 2015-2030. 2015, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Bangladesh.

- World Health Organization, Standards for improving quality of maternal and newborn care in health facilities. 2016: Geneva.

- World Health Organization, WHO Recommendations on Postnatal Care of the Mother and Newborn. 2014: Geneva.

- Baqui, A.H.; et al. Effect of timing of first postnatal care home visit on neonatal mortality in Bangladesh: A observational cohort study. BMJ 2009, 339, b2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, N.; et al. Utilisation of postnatal care in Bangladesh: Evidence from a longitudinal study. Health Soc. Care Community 2002, 10, 492–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, U.; et al. Immediate and early postnatal care for mothers and newborns in rural Bangladesh. 2006, 24, 508–518. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mosiur Rahman, M.; et al. Factors affecting the utilisation of postpartum care among young mothers in Bangladesh. Health Soc. Care Community 2011, 19, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, A.K.; et al. Inequalities in reproductive healthcare utilization: Evidence from Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey. World Health Popul. 2007, 9, 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (NIPORT), N.I.o.P.R.a.T., U.-C. MEASURE Evaluation, USA, and b. icddr, USAID, Bangladesh Maternal Mortality and Health Care Survey BMMS, in Final Report. 2010, 1-12.

- Okawa, S.; et al. Quality gap in maternal and newborn healthcare: A cross-sectional study in Myanmar. BMJ Glob. Health 2019, 4, e001078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baqui, A.H.; et al. Effect of timing of first postnatal care home visit on neonatal mortality in Bangladesh: A observational cohort study. BMJ 2009, 339, b2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, M.; Haque, S.E.; Zahan, S. Factors affecting the utilisation of postpartum care among young mothers in Bangladesh. Health Soc. Care Community 2011, 19, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, M.; Tarafder, T.; Mostofa, G. Modes of delivery assistance in Bangladesh. Tanzan. J. Health Res. 2008, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohan, D.; et al. Determinants of postnatal care use at health facilities in rural Tanzania: Multilevel analysis of a household survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015, 15, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fosu, G.B.J.S.s. and medicine, Childhood morbidity and health services utilization: Cross-national comparisons of user-related factors from DHS data. 1994, 38, 1209–1220. [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, K.; et al. Effective linkages of continuum of care for improving neonatal, perinatal, and maternal mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0139288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, C.; et al. Factors associated with the use and quality of antenatal care in Nepal: A population-based study using the demographic and health survey data. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014, 14, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ononokpono, D.N.; et al. Does it really matter where women live? A multilevel analysis of the determinants of postnatal care in Nigeria. Matern. Child Health J. 2014, 18, 950–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Hong, R. Levels and determinants of continuum of care for maternal and newborn health in Cambodia-evidence from a population-based survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015, 15, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahariya, C.J.I.j.o.c.m.o.p.o.I.A.o.P. and S. Medicine, Cash incentives for institutional delivery: Linking with antenatal and post natal care may ensure ‘continuum of care’in India. 2009, 34, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Yunus, A.; et al. Determinants of postnatal care services utilization in Pakistan-insights from Pakistan demographic and health survey (PDHS) 2006-07. 2013, 18, 1440–1447. [CrossRef]

- Chungu, C.; et al. Place of delivery associated with postnatal care utilization among childbearing women in Zambia. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhaher, E.; et al. Factors associated with lack of postnatal care among Palestinian women: A cross-sectional study of three clinics in the West Bank. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2008, 8, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borders, N.J.J.o.m. and w.s. health, After the afterbirth: A critical review of postpartum health relative to method of delivery. 2006, 51, 242–248. 2006, 51, 242–248. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, O.M.; et al. Length of stay after childbirth in 92 countries and associated factors in 30 low-and middle-income countries: Compilation of reported data and a cross-sectional analysis from nationally representative surveys. PLOS Med. 2016, 13, e1001972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndugga, P.; et al. Determinants of early postnatal care attendance: Analysis of the 2016 Uganda demographic and health survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).