Submitted:

14 December 2023

Posted:

15 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

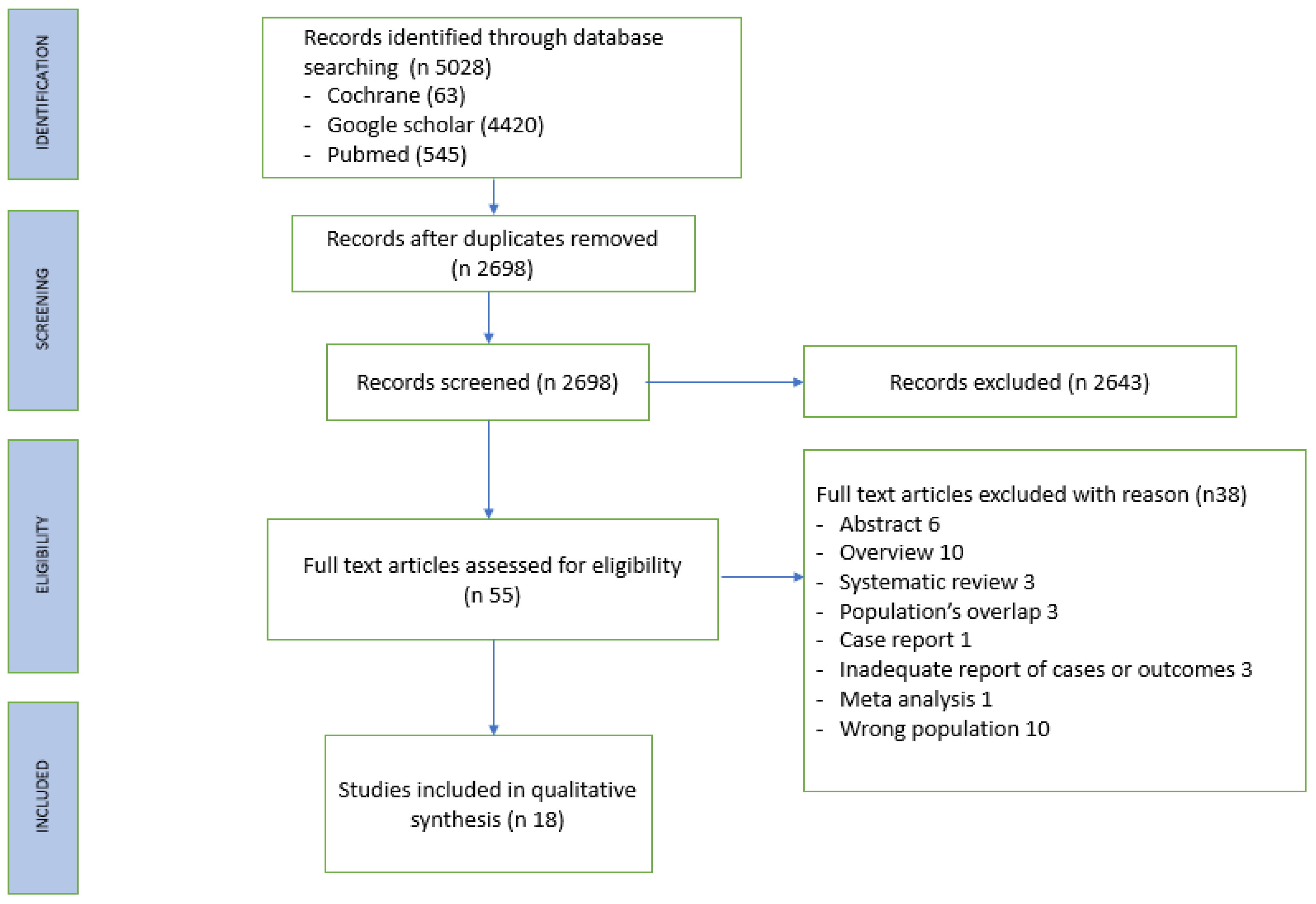

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Literature search

Data extraction

RESULTS

Study characteristic

Patient characteristics

DISCUSSION

CONCLUSIONS

REFERENCES

- Maclellan RA, Greene AK. Lymphedema. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2014;23(4):191-197. [CrossRef]

- Taghian NR, Miller CL, Jammallo LS, O'Toole J, Skolny MN. Lymphedema following breast cancer treatment and impact on quality of life: a review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2014;92(3):227-234. [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen MG, Toyserkani NM, Sørensen JA. The effect of prophylactic lymphovenous anastomosis and shunts for preventing cancer-related lymphedema: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Microsurgery. 2018;38(5):576-585. [CrossRef]

- Johnson AR, Kimball S, Epstein S, et al. Lymphedema Incidence After Axillary Lymph Node Dissection: Quantifying the Impact of Radiation and the Lymphatic Microsurgical Preventive Healing Approach. Ann Plast Surg. 2019;82(4S Suppl 3): S234-S241. [CrossRef]

- Stuiver MM, ten Tusscher MR, Agasi-Idenburg CS, Lucas C, Aaronson NK, Bossuyt PM. Conservative interventions for preventing clinically detectable upper-limb lymphoedema in patients who are at risk of developing lymphoedema after breast cancer therapy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(2):CD009765. Published 2015 Feb 13. [CrossRef]

- Badger C, Preston N, Seers K, Mortimer P. Physical therapies for reducing and controlling lymphoedema of the limbs. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(4):CD003141. Published 2004 Oct 18. [CrossRef]

- Markkula SP, Leung N, Allen VB, Furniss D. Surgical interventions for the prevention or treatment of lymphoedema after breast cancer treatment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;2(2):CD011433. Published 2019 Feb 19. [CrossRef]

- Granzow JW, Soderberg JM, Kaji AH, Dauphine C. Review of current surgical treatments for lymphedema. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(4):1195-1201. [CrossRef]

- Kung TA, Champaneria MC, Maki JH, Neligan PC. Current Concepts in the Surgical Management of Lymphedema. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;139(4):1003e-1013e. [CrossRef]

- Campisi CC, Ryan M, Boccardo F, Campisi C. LyMPHA and the prevention of lymphatic injuries: a rationale for early microsurgical intervention. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2014;30(1):71-72. [CrossRef]

- Boccardo F, Casabona F, De Cian F, et al. Lymphatic microsurgical preventing healing approach (LYMPHA) for primary surgical prevention of breast cancer-related lymphedema: over 4 years follow-up [published correction appears in Microsurgery. 2015 Jan;35(1):83. DeCian, Franco [corrected to De Cian, Franco]. Microsurgery. [CrossRef]

- Schwarz GS, Grobmyer SR, Djohan RS, et al. Axillary reverse mapping and lymphaticovenous bypass: Lymphedema prevention through enhanced lymphatic visualization and restoration of flow. J Surg Oncol. 2019;120(2):160-167. [CrossRef]

- Shaffer K, Cakmakoglu C, Schwarz GS, et al. Lymphedema Prevention Surgery: Improved Operating Efficiency Over Time. Ann Surg Oncol. 2020;27(12):4695-4701. [CrossRef]

- Johnson AR, Fleishman A, Granoff MD, et al. Evaluating the Impact of Immediate Lymphatic Reconstruction for the Surgical Prevention of Lymphedema. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2021;147(3):373e-381e. [CrossRef]

- Cook JA, Sasor SE, Loewenstein SN, et al. Immediate Lymphatic Reconstruction after Axillary Lymphadenectomy: A Single-Institution Early Experience. Ann Surg Oncol. 2021;28(3):1381-1387. [CrossRef]

- Boccardo FM, Casabona F, Friedman D, et al. Surgical prevention of arm lymphedema after breast cancer treatment. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(9):2500-2505. [CrossRef]

- Feldman S, Bansil H, Ascherman J, et al. Single Institution Experience with Lymphatic Microsurgical Preventive Healing Approach (LYMPHA) for the Primary Prevention of Lymphedema. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(10):3296-3301. [CrossRef]

- Herremans KM, Cribbin MP, Riner AN, et al. Five-Year Breast Surgeon Experience in LYMPHA at Time of ALND for Treatment of Clinical T1-4N1-3M0 Breast Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2021;28(10):5775-5787. [CrossRef]

- Weinstein B, Le NK, Robertson E, et al. Reverse Lymphatic Mapping and Immediate Microsurgical Lymphatic Reconstruction Reduces Early Risk of Breast Cancer-Related Lymphedema. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2022;149(5):1061-1069. [CrossRef]

- Boccardo F, Casabona F, De Cian F, et al. Lymphedema microsurgical preventive healing approach: a new technique for primary prevention of arm lymphedema after mastectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(3):703-708. [CrossRef]

- Casabona F, Bogliolo S, Valenzano Menada M, Sala P, Villa G, Ferrero S. Feasibility of axillary reverse mapping during sentinel lymph node biopsy in breast cancer patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(9):2459-2463. [CrossRef]

- Han Ang C, Wong M. Incorporation of the Vascularized Serratus Fascia Flap during Latissimus Dorsi Flap Harvest to Minimize Morbidity after Axillary Clearance. Journal of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 2022; 1(2):58-62. [CrossRef]

- Lipman K, Luan A, Stone K, Wapnir I, Karin M, Nguyen D. Lymphatic Microsurgical Preventive Healing Approach (LYMPHA) for Lymphedema Prevention after Axillary Lymph Node Dissection-A Single Institution Experience and Feasibility of Technique. J Clin Med. 2021;11(1):92. Published 2021 Dec 24. [CrossRef]

- Pierazzi DM, Arleo S, Faini G. Distally Prophylactic Lymphaticovenular Anastomoses after Axillary or Inguinal Complete Lymph Node Dissection Followed by Radiotherapy: A Case Series. Medicina (Kaunas). 2022;58(2):207. Published 2022 Jan 29. [CrossRef]

- Hahamoff M, Gupta N, Munoz D, et al. A Lymphedema Surveillance Program for Breast Cancer Patients Reveals the Promise of Surgical Prevention. J Surg Res. 2019;244:604-611. [CrossRef]

- Yoon JA, Lee HS, Lee JW, Kim JH. Six-Month Follow-up for Investigating the Effect of Prophylactic Lymphovenous Anastomosis on the Prevention of Breast Cancer-Related Lymphedema: A Preliminary Study in a Single Institution. Archives of Hand and Microsurgery. 2021;26(4):276-84. [CrossRef]

- Ozmen T, Layton C, Friedman-Eldar O, et al. Evaluation of Simplified Lymphatic Microsurgical Preventing Healing Approach (SLYMPHA) for the prevention of breast cancer-related lymphedema after axillary lymph node dissection using bioimpedance spectroscopy. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2022;48(8):1713-1717. [CrossRef]

- Yoshimatsu H, Karakawa R, Fuse Y, Yano T. Simultaneous Lymphatic Superficial Circumflex Iliac Artery Perforator Flap Transfer from the Zone 4 Region in Autologous Breast Reconstruction Using the Deep Inferior Epigastric Artery Perforator Flap: A Proof-of-Concept Study. J Clin Med. 2022;11(3):534. [CrossRef]

- Casley-Smith JR. Measuring and representing peripheral oedema and its alterations. Lymphology. 1994;27(2):56-70.

- Kleinhans E, Baumeister RG, Hahn D, Siuda S, Büll U, Moser E. Evaluation of transport kinetics in lymphoscintigraphy: follow-up study in patients with transplanted lymphatic vessels. Eur J Nucl Med. 1985;10(7-8):349-352. [CrossRef]

- Thompson M, Korourian S, Henry-Tillman R, et al. Axillary reverse mapping (ARM): a new concept to identify and enhance lymphatic preservation. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14(6):1890-1895. [CrossRef]

- Nos C, Lesieur B, Clough KB, Lecuru F. Blue dye injection in the arm in order to conserve the lymphatic drainage of the arm in breast cancer patients requiring an axillary dissection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14(9):2490-2496. [CrossRef]

- Ochoa D, Korourian S, Boneti C, Adkins L, Badgwell B, Klimberg VS. Axillary reverse mapping: five-year experience. Surgery. 2014;156(5):1261-1268. [CrossRef]

- Tummel E, Ochoa D, Korourian S, et al. Does Axillary Reverse Mapping Prevent Lymphedema After Lymphadenectomy?. Ann Surg. 2017;265(5):987-992. [CrossRef]

- Yue T, Zhuang D, Zhou P, et al. A Prospective Study to Assess the Feasibility of Axillary Reverse Mapping and Evaluate Its Effect on Preventing Lymphedema in Breast Cancer Patients. Clin Breast Cancer. 2015;15(4):301-306. [CrossRef]

- Boneti C, Korourian S, Bland K, et al. Axillary reverse mapping: mapping and preserving arm lymphatics may be important in preventing lymphedema during sentinel lymph node biopsy. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206(5):1038-1044. [CrossRef]

- Shimotsuma M, Shields JW, Simpson-Morgan MW, et al. Morpho-physiological function and role of omental milky spots as omentum-associated lymphoid tissue (OALT) in the peritoneal cavity. Lymphology. 1993;26(2):90-101.

- Chen WF. How to Get Started Performing Supermicrosurgical Lymphaticovenular Anastomosis to Treat Lymphedema. Ann Plast Surg. 2018;81(6S Suppl 1):S15-S20. [CrossRef]

- Johnson AR, Asban A, Granoff MD, et al. Is Immediate Lymphatic Reconstruction Cost-effective?. Ann Surg. 2021;274(6):e581-e588. [CrossRef]

- Fu MR. Breast cancer-related lymphedema: Symptoms, diagnosis, risk reduction, and management. World J Clin Oncol. 2014;5(3):241-247. [CrossRef]

- DiSipio T, Rye S, Newman B, Hayes S. Incidence of unilateral arm lymphoedema after breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(6):500-515. [CrossRef]

- Basta MN, Wu LC, Kanchwala SK, et al. Reliable prediction of postmastectomy lymphedema: The Risk Assessment Tool Evaluating Lymphedema. Am J Surg. 2017;213(6):1125-1133.e1. [CrossRef]

- Chen WF, Knackstedt R. Delayed Distally Based Prophylactic Lymphaticovenular Anastomosis: Improved Functionality, Feasibility, and Oncologic Safety?. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2020;36(9):e1-e2. [CrossRef]

| Article | Adjuvant therapy | LVA shunting technique | LVA feasibility | Follow-up (months) | Operating time (minutes) | Method of lymphedema diagnosis | Cases with lymphedema | Controls with lymphedema | Cases with lymphedema who received adjuvant radiotherapy | OCEBM and JADAD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boccardo 2011 | Cases: RT (11/23) Controls: RT (12/23) |

Sleeve | 23/23 | 18 | 15-20 | V | 1/23 (4%) | 7/23 (30%) | 1/1 | 2 and 5 |

| Feldman 2015 | Cases: RT (15/24), CT (23/24) Controls: RT (6/8), CT (7/8) |

Sleeve | 24/32 | From 3 to 24 | 45 | V | 3/24 (13%) | 4/8 (50%) | 3/3 | 3 and 3 |

| Hahamoff 2019 | Cases: RT (8/8),neoCT (5/8), adCT (4/8); Controls: RT (6/10), neoCT (4/10), adCT (4/10) |

Sleeve | 8/8 | From 15 to 20 | From 32 to 95 | CA, BS | 0/8 (0%) | 4/10 (40%) | 0/0 | 3 and 3 |

| Herremans 2021 | Cases: RT (67/76), CT (58/76), neoCT (36/76) Controls: RT (50/56), CT (42/56), neoCT (20/56) |

Sleeve | 76/84 | 60 | nr | CA, BS, LQOLQ | 10/76 (13.2%) | 16/56 (28.6%) | nr | 3 and 4 |

| Yoon 2021 | Cases: RT (17/21), CT (16/21); Controls: RT (36/48), CT (38/48) |

ETE LVA | 21/21 | 6 | From 30 to 60 | CA, BS | 0/21 (0%) | 9/48 (18.8%) | 0/0 | 2 and 5 |

| Ozmen 2022 | Cases: RT (89/110); Controls: RT (68/84) |

Sleeve | Nr | From 10 to 84 | nr | CA, BS | 18/110 (16%) | 57/84 (68%) | nr | 3 and 4 |

| Weinstein 2022 | Cases: RT (46/66), neoCT (56/66) adCT (26/66); Controls: RT (8/12), neoCT (8/12), adCT (8/12) | ETE or ETS LVA | Nr | 8 on average | nr | CA, BS | 4/66 (6%) | 1/12 (8%) | 3/4 | 3 and 4 |

| Article | Adjuvant therapy | LVA shunting technique | LVA feasibility | Follow-up (months) | Operating time (minutes) | Method of lymphedema diagnosis | Cases with lymphedema | Cases with lymphedema who received adjuvant radiotherapy | OCEBM and JADAD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boccardo 2009 | RT (7/18) | Sleeve | 18/19 (95%) | 12 | 15 | CA, LS | 0/18 (0%) | 0/0 | 4 and 3 |

| Casabona | RT (8/8), CT (0/8) | Sleeve | 8/9 (89%) | 9 | 17 | CA | 0/8 (0%) | 0/0 | 4 and 3 |

| Boccardo 2014 | RT (35/74) | Sleeve | 74/78(95%) | 48 | 48 | V, LS | 3/74(4%) | 3/3 | 4 and 3 |

| Johnson 2019 | RT (26/32), CT (19/32) | Sleeve | nr | 12 | nr | CA, BS | 1/32 (3.1%) | 1/32 | 4 and 4 |

| Scharwz 2019 | RT (52/58), neoCT (43/58), adCT (10/58) | 37/58 ETE LVA, 21/58 sleeve | 58/60 (97%) | 29 | 95 | CA, BS | 2/43 (4.6%) | 2/2 | 4 and 3 |

| Cook 2020 | RT (22/33), neoCT (24/33) | Sleeve | 33/33 (100%) | 12 | nr | CA, LS | 3/33(9%) | 3/3 | 4 and 4 |

| Shaffer 2020 | RT (82/88), neoCT (61/88), adCT (20/88), neo + adCT (1/88) | ETE LVA or sleeve | 88/88 (100%) | 14.6 on average | From 161 to 253 | CA, BS | 5/88(6%) | 4/5 | 4 and 4 |

| Chuan 2021 | RT (3/3), neo CT (2/3) | Vascularized serratus anterior fascia flap | nr | 48 | nr | CA | 0/3(0%) | 0/0 | 4 and 3 |

| Lipman 2022 | RT (16/19) | ETE or ETS LVA | nr | 10 on average | From 32 to 95 | CA,BS | 1/19(5%) | nr | 4 and 3 |

| Pierazzi 2022 | RT (5/5) | DLVA | 5/5 (100%) | 12 | nr | CA | 0/5(0%) | 0/0 | 4 and 3 |

| Yoshimatsu 2022 | RT (2/4) | SCIP flap with DIEP | 4/4 (100%) | From 24 to 48 | nr | V | 0/4(0%) | 0/0 | 4 and 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).