Submitted:

18 December 2023

Posted:

18 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and procedure

2.2. Measurement

2.3. Data analysis

3. Results

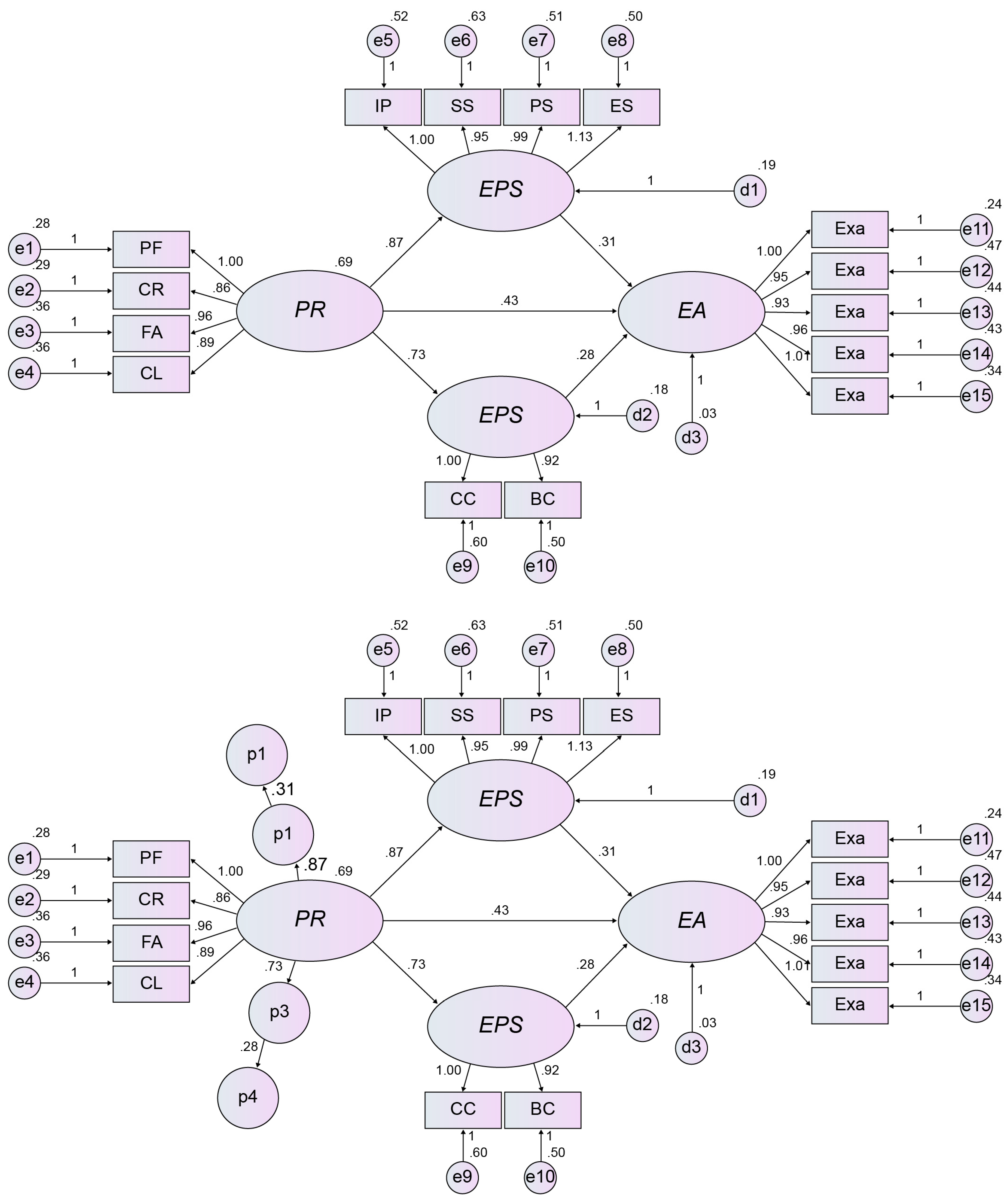

3.1. Measurement model

3.2. Hypotheses Testing

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kim, B.R.; Yun, J.S. Effect of adolescents’ leisure attitude on exercise adherence: Mediating effect of health promotion behavior. J Kor Soc Study Phys Educ 2022, 27, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brajša-Žganec, A.; Merkaš, M.; Šverko, I. Quality of life and leisure activities: How do leisure activities contribute to subjective well-being? Soc Indic Res 2011, 102, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.M. A study on the promotion of youth leisure activities. J Korea Youth Activity 2020, 6, 71–94. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, J.; Kim, D.H. Analysis of differences in physical activity of general high school students according to gender, academic achievement level, and economic level in COVID-19. Kor Assoc Learn Centered Curric Instr 2022, 22, 541–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.H. The validation of an exercise adherence questionnaire for leisure and recreation. Korean J Phys Educ 2004, 43, 237–247. [Google Scholar]

- Dishman, R.K. Exercise Adherence: Its Impact on Public Health; Human Kinetics Books: Champaign, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Dishman, R.K. Advances in Exercise Adherence; Human Kinetics Publishers: Champaign, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, S.H.; Kim, C.W. Analysis of participating motivation, exercise adherence, and adherence intention of college tennis dub members. Korean J Phys Educ 2004, 43, 231–238. [Google Scholar]

- Beard, J.G.; Ragheb, M.G. Measuring leisure satisfaction. J Leis Res 1980, 12, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.H. Flow or commitment? A conceptual ambiguity in sport psychology. Korean Soc Sport Psychol 2011, 22, 157–168. [Google Scholar]

- Scanlan, T.K.; Carpenter, P.J.; Simons, J.P.; Schmidt, G.W.; Keeler, B. An introduction to the sport commitment model. J Sport Exerc Psychol 1993, 15, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brickman, P. Commitment, Conflict and Caring; Prentice Hall: Old Tappan, NJ, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Cronin, J.J., Jr.; Brady, M.K.; Hult, G.T.M. Assessing the effects of quality, value, and customer satisfaction on consumer behavioral intentions in service environments. J Retail 2000, 76, 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iso-Ahola, S.E. The Social Psychology of Leisure and Recreation; W. C. Brown Co. Publishers: Dubuque, Iowa, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.K.; Joo, H. The structural relationship among grit, mindset and exercise commitment in physical education as liberal education class participants. Korean J Phys Educ 2019, 58, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, E.E.; Spreitzer, E.A. Family Influence and Involvement in Sports. Res Q Am Assoc Health Phys Educ Recreat 1973, 44, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H.; Lee, H.S. An analysis on relationship among teaching method types of instructor, satisfaction and participation adherence intention of school sports club. J. Korean Soc. Study Phys. Educ. 2020, 25, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Lee, S. The relationship among social support perception, sport confidence, exercise commitment and continuation of middle school students participating in school sports clubs: Structural equation modelling. Korean J. Phys. Educ. 2019, 58, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, D.G.; Bussey, K. Social Development; Prentice-Hall: London, England, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- So, Y.H.; Cho, C.H. Relationship among leader intimacy, peer relation, training intention to continue, and intention to dropout of taekwondo training children. J. Sport Leis. Studies 2013, 54, 769–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M.; Larson, R. Being Adolescent; Basic Books: London, England, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Rain, J.S.; Lane, I.M.; Steiner, D.D. A current look at the job satisfaction/life satisfaction relationship: Review and future consideration. Hum Relat. 1991, 44, 287–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burleson, B.R.; Albrecht, T.L.; Sarason, I.G. Communication of social support: Messages, interactions, relationships, and community; Sage Publications, Inc., 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S. (2000). Social support measurement and intervention. A guide for 356 health and social scientists, 13.

- Goldsmith, D.J. Advances in personal relationships: Communicating social support; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, England, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith, D.J.; Albrecht, T.L. Social support, social networks, and health. In The Routledge Handbook of Health Communication; 2011; pp. 361–374. [Google Scholar]

- Ash, C.; Huebner, E.S. Life satisfaction reports of gifted middle-school children. Sch. Psychol. Q. 1998, 13, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.Y.; Kim, Y.J. Relationship between self-management, peer relationship and schoollife satisfaction of student-athletes. Korean Soc. Sports Sci. 2017, 26, 983–992. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.J.; Jun, J.S. The dual mediating effect of peer relationship, teacher relationship, and grit on the relationship between parents’ rearing attitude and life satisfaction in adolescents. J. Korean Soc. Gifted Talented 2021, 20, 35–56. [Google Scholar]

- Purpora, C.; Blegen, M.A. Job satisfaction and horizontal violence in hospital staff registered nurses: the mediating role of peer relationships. J. Clin. Nurs. 2015, 24, 2294–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.W.; Lee, C.H. The relationship between peer group and academic engagement of specialized vocational high school students. Korean J. Technol. Educ. 2014, 14, 125–148. [Google Scholar]

- Yune, S.J.; Kang, S.H. The effect of family strength, peer relationship and self-determination on learning flow perceived by middle school students. Korea Educ. Rev. 2012, 18, 235–259. [Google Scholar]

- So, Y.H.; Cho, C.H. Relationship among Leader Intimacy, Peer Relation, Training Intention to Continue, and Intention to Dropout of Taekwondo Training Children. J Sport Leis Stud 2013, 54, 769–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, O.B. Developmental Psychology; Hakjisa: Seoul, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Heo, M.J.; Noh, M.W.; Choi, Y.S. The Influence of Adolescents` Self-Esteem on Life Satisfaction: Verifying Moderated Mediation of Peer Relations Mediated by Altruism and Self-Regulation. J Family Relat 2016, 21, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M. The Influence of Teacher’s Teaching Style in Elementary School Sports Club and Social Supports on Exercise Adherence Intention: The Mediating Effect of Lesson Satisfaction and Immersion. Unpublished Masters Dissertation, Seoul, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, J.G.; Asher, S.R. Peer relations and later personal adjustment: Are low-accepted children at risk? Psychol. Bull. 1987, 102, 357–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.T. A Study of the Development and the Measurement of Ego-Identity in Korean Youth. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, DaeJeon, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Park, K.M.; Kim, H.H. The effects of emotional education program on emotional intelligence and friendship of elementary school students. J. Element. Educ. 2007, 14, 63–80. [Google Scholar]

- Park, M.R. The effects for the school life satisfactions and peer relation through the enjoyment from after-school sport activities. Unpublished Masters Dissertation, Graduate School of Sookmyung Women’s University of Education, Seoul, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.S. The Effect of Participation in Leisure Sports in Elementary Students on Self-Esteem and Friendship. Unpublished Masters Dissertation, Incheon, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, H.M.; Lee, J.Y. The Relationship Between Leisure Satisfaction and Teachers Participant Base on Lueschen's Types of Leisure Activity. Korean J Phys Educ 1997, 36, 271–280. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.R. The Influence of Participation Motivation on the Satisfaction of Winter Sports Activity Participants : Focused on ski & snowboard participants. Korean J Phys Educ 2000, 39, 116–125. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, Y.G. The influence of sport participation motivation, arousal seeking and affects on the behavior of sport commitment. Graduate School of Pusan National University, Busan, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, S.H. The development of a Korean exercise adherence scale. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Graduate School of Seoul University, Seoul, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, C.B.; Lindsey, R. Concepts of physical fitness; Wm. C. Brown Communication: Dubuque, IA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Predicting and understanding consumer behavior: Attitude-behavior correspondence. Understanding Attitudes. Predict. Soc. Behav. 1980, 1, 148–172. [Google Scholar]

- Robert, A. (1992). Amateurs, Professionals, and Serious Leisure.

- Stebbins, R.A. Serious leisure: A conceptual statement. Pac. Sociol. Rev. 1982, 25, 251–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stebbins, R.A. The costs and benefits of hedonism: Some consequences of taking casual leisure seriously. Leis. Stud. 2001, 20, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhrmester, D.; Furman, W. Perceptions of sibling relationships during middle childhood and adolescence. Child Dev. 1990, 61, 1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bum, C.H.; Jeon, I.K. Structural relationships between students’ social support and self-esteem, depression, and happiness. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2016, 44, 1761–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furman, W.; Buhrmester, D. Age and sex differences in perceptions of networks of personal relationships. Child. Dev. 1992, 63, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrido, L.E.; Abad, F.J.; Ponsoda, V. Are fit indices really fit to estimate the number of factors with categorical variables? Some cautionary finding via Monte Carlo simulation. Psychol Methods 2016, 21, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhrmester, D.; Furman, W. Perceptions of sibling relationships during middle childhood and adolescence. Child development 1990, 61, 1387–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bum, C.H.; Jeon, I.K. Structural relationships between students' social support and self-esteem, depression, and happiness. Social Behav Personal 2016, 44, 1761–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furman, W.; Buhrmester, D. Age and sex differences in perceptions of networks of personal relationships. Child development 1992, 63, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct and Item | λ | α | AVE | C.R. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peer Relationship (PR) | ||||

| Presence of Friendship (PF) | .939 | .719 | .928 | |

| PF 1 | .869 | |||

| PF 2 | .832 | |||

| PF 3 | .896 | |||

| PF 4 | .871 | |||

| PF 6 | .881 | |||

| Continuation of Relationship (CR) | .897 | .676 | .893 | |

| CR 7 | .860 | |||

| CR 9 | .766 | |||

| CR 10 | .819 | |||

| CR 11 | .863 | |||

| Friend Adaptation (FA) | .914 | .681 | .895 | |

| FA 13 | .845 | |||

| FA 14 | .875 | |||

| FA 15 | .840 | |||

| FA 17 | .853 | |||

| Co-living (CL) | .862 | .649 | .846 | |

| CL18 | .753 | |||

| CL 19 | .852 | |||

| CL 20 | .868 | |||

| Exercise Participation Satisfaction (EPS) | ||||

| Inside Psychology (IP) | .971 | .832 | .961 | |

| IP 1 | .926 | |||

| IP 2 | .934 | |||

| IP 3 | .962 | |||

| IP 4 | .945 | |||

| IP 5 | .899 | |||

| Social Satisfaction (SS) | .975 | .881 | .967 | |

| SS 7 | .947 | |||

| SS 8 | .972 | |||

| SS 9 | .953 | |||

| SS 10 | .942 | |||

| Physical Satisfaction (PS) | .952 | .784 | .935 | |

| PS 11 | .903 | |||

| PS 13 | .895 | |||

| PS 14 | .923 | |||

| PS 15 | .926 | |||

| Environmental Satisfaction (ES) | .970 | .845 | .956 | |

| ES 16 | .909 | |||

| ES 17 | .962 | |||

| ES 18 | .961 | |||

| ES 19 | .946 | |||

| Exercise Commitment (EC) | ||||

| Cognitive Commitment (CC) | .944 | .727 | .914 | |

| CC 3 | .964 | |||

| CC 4 | .811 | |||

| CC 5 | .810 | |||

| CC 6 | .960 | |||

| Behavioral Commitment (BC) | .929 | .739 | .919 | |

| BC 8 | .872 | |||

| BC 9 | .886 | |||

| BC 11 | .870 | |||

| BC 12 | .875 | |||

| Exercise Adherence intention (EA) | ||||

| Exercise Ability (ExA) | .877 | .689 | .869 | |

| ExA 1 | .863 | |||

| ExA 2 | .820 | |||

| ExA 4 | .837 | |||

| Exercise Habit (ExH) | .880 | .658 | .852 | |

| ExH 5 | .800 | |||

| ExH 6 | .894 | |||

| ExH 7 | .842 | |||

| Exercise Environment (ExE) | .918 | .700 | .903 | |

| ExE 8 | .837 | |||

| ExE 9 | .827 | |||

| ExE 10 | .836 | |||

| ExE 11 | .929 | |||

| Exercise Interest (ExI) | .838 | .568 | .798 | |

| ExI 12 | .772 | |||

| ExI 13 | .796 | |||

| ExI 14 | .823 | |||

| Exercise Friend (ExF) | .861 | .652 | .847 | |

| ExF15 | .702 | |||

| ExF 16 | .867 | |||

| ExF 17 | .915 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | |

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| 2 | .656** | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 3 | .693** | .631** | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 4 | .654** | .660** | .649** | 1 | |||||||||||

| 5 | .573** | .585** | .543** | .505** | 1 | ||||||||||

| 6 | .504** | .452** | .487** | .431** | .484** | 1 | |||||||||

| 7 | .518** | .526** | .495** | .471** | .553** | .567** | 1 | ||||||||

| 8 | .533** | .560** | .493** | .473** | .583** | .623** | .629** | 1 | |||||||

| 9 | .500** | .415** | .431** | .410** | .390** | .457** | .449** | .516** | 1 | ||||||

| 10 | .457** | .489** | .399** | .364** | .515** | .374** | .483** | .424** | .479** | 1 | |||||

| 11 | .693** | .678** | .627** | .613** | .683** | .507** | .595** | .633** | .454** | .588** | 1 | ||||

| 12 | .581** | .538** | .528** | .519** | .575** | .472** | .540** | .508** | .447** | .450** | .644** | 1 | |||

| 13 | .602** | .549** | .614** | .528** | .487** | .478** | .486** | .526** | .488** | .399** | .595** | .603** | 1 | ||

| 14 | .587** | .535** | .539** | .538** | .552** | .508** | .501** | .567** | .504** | .477** | .643** | .553** | .498** | 1 | |

| 15 | .648** | .600** | .594** | .603** | .578** | .488** | .530** | .550** | .544** | .475** | .643** | .567** | .674** | .673** | 1 |

| M | 3.714 | 3.614 | 3.609 | 3.622 | 3.540 | 3.833 | 3.582 | 3.738 | 3.460 | 3.260 | 3.642 | 3.561 | 3.592 | 3.235 | 3.497 |

| SD | .990 | .895 | 1.001 | .957 | 1.111 | 1.127 | 1.097 | 1.189 | 1.071 | .981 | .932 | 1.017 | .987 | 1.004 | .988 |

| Path of Latent Variables | Direct effect | Indirect effect | p-value | Hypothesis testing | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | PR -> EPS | .866(.855) | <.001 | Supported | |

| H2 | PR -> EC | .733 (.823) | <.001 | Supported | |

| H3 | PR -> EA | .427(.451) | <.001 | Supported | |

| H4 | EPS -> EA | .309(.331) | <.001 | Supported | |

| H5 | EC -> EA | .281(.264) | .012 | Supported | |

| H6 | PR -> EPS -> EA | .268 | .005 | Supported | |

| H7 | PR -> EC -> EA | .206 | .014 | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).