1. Introduction

Sugarcane, a perennial crop in the Genus Saccharum, has served as a key feedstock for sugar production across the globe [1]. In light of climate change, it is becoming increasingly important to replace fossil fuels with sustainable bio-energy sources, such as sugarcane [2,3]. In response to growing interest in biomass and ethanol, bio-energy traits have gained importance in recent sugarcane breeding programme. The present commercial sugarcane hybrids are complex polyploidy aneuploids, primarily derived from the interspecific hybridization between Saccharum officinarum and Saccharum spontaneum. Modern sugarcane cultivars contain 70–80% of the genome of Saccharum officinarum, contributed to thick stalks and high sucrose content [4]. Conversely, S. spontaneum incorporates high fiber content, high tillering, ratooning and resistance to various diseases and abiotic stresses in the present cultivars [5]. However slow rate of genetic gain and narrow genetic base pose an immediate concern for sugarcane researchers, which necessitates to widen its genetic base using the allied genera. Therefore, attempts are made to cross the saccharum with allied genera to broaden the genetic base of future sugarcane varieties.

Erianthus is part of the 'Saccharum complex' as classified by Mukherjee in 1957 [6], along with four additional interbreeding genera: i.e., Saccharum L., Miscanthus sect. Diandra Keng, Narenga Bor., and Sclerostachya Hack. There is a notable emphasis to harness the potential of Erianthus genus, a wild relative of Saccharum, to introgress the desired agronomic traits. Among Erianthus, two species viz., Erianthus arundinaceus and E. procerus, gained recognition due to their agronomically desired traits such as high biomass, profuse tillering, robust ratooning potential, resilience to both biotic and abiotic stresses, including drought. However, the challenges in intergeneric crosses between Saccharum and Erianthus lies on difficulty of the process of hybridization, cross incompatibility and sterility of F1 hybrids, impeding further advancement of these efforts. Nevertheless, after subsequent attempts the successful production of intergeneric hybrids from Erianthus has been documented in previous studies [7–10]. Lacks of vegetative cane and large droopy silky panicles in E. procerus (2n = 40) make it different from E. arundinaceus (2n=30, 40 and 60) and E. kanashiroi Ohwi (2n = 60) [11]. Efforts are made at ICAR-Sugarcane Breeding Institute, Coimbatore, India to generate the novel hybrids from Erianthus procerus and Saccharum officinarum [12]. Evaluation of potential promising hybrids for high winter ratooning, frost tolerance is a standard practice in countries experiencing low-temperature conditions. In India, mega-sugarcane cultivating area belonging to North West Zone of the country, characterized by subtropical climate, where sugarcane crop is planted during autumn season, subjected to chilling (<10°C) and sub-zero temperature in the months of December -January, resulting very slow growth or negligible cane growth and sprouting. Therefore, when sugarcane crop is ratooned during the peak winter season, many of popular varieties are not capable of giving better ratooning, which results in 10-20% reduction in ratoon yields compared to plant crop [14]. Also multi-ratooning is not gaining popularity due to harvesting of preceding crop and ratoons coincide with the winter period. Hence, there is a paramount significance in improving winter sprouting potential to increase the cane yield and sugar recovery in subtropical regions. Additionally, autumn planting with multi-ratooning is an important factor to improve the sugarcane yield and sugar recovery in subtropical climate of India [13]. The integration of wild genome in the resultant hybrids show improved resilience to water scarcity, increased biomass yield, resistance to pest and diseases and adaptability to varied environments [12]. In subtropical climates, emphasis is placed on the identification of sugarcane varieties with higher yields, increased sugar content and resistance to diseases. Additionally, priority is given to those varieties that exhibits improved winter ratooning ability. Therefore, germplasm with better winter sprouting potential is viewed as way forward to address the problem of winter ratooning in subtropical sugarcane breeding programme.

The present study was planned to evaluate the Erianthus procerus genome introgressed Saccharum hybrids for their ratooning potential under subtropical climate. These intergeneric hybrids could serve as valuable sources for further introgression of high ratooning potential and biotic and abiotic stress tolerance into the cultivated sugarcane.

2. Results

2.1. Weather Statistics of the Experimental Site

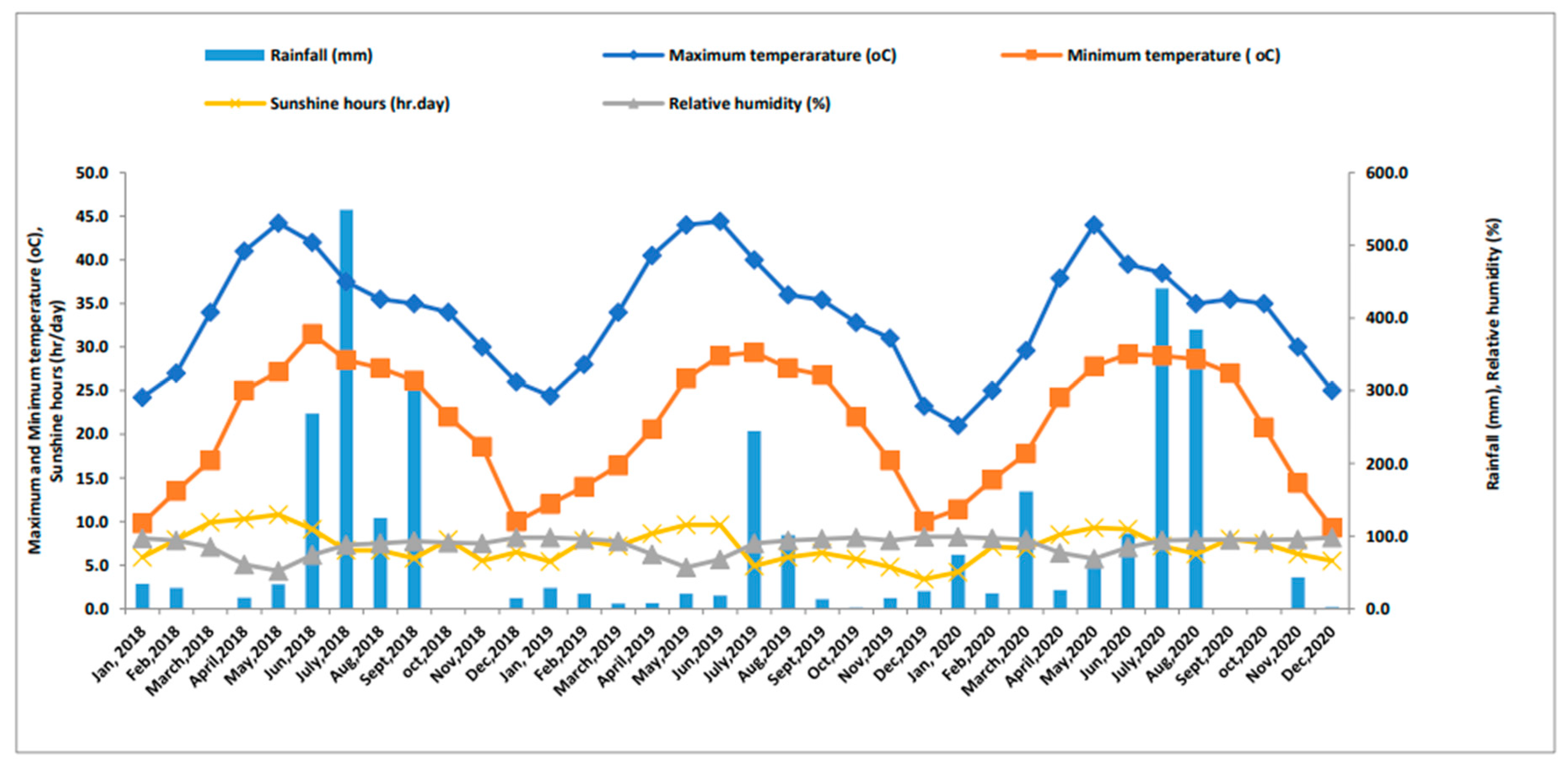

The maximum temperatures range from 34–45 °C in summer, and minimum temperatures range from 5–8 °C in winter. The maximum and minimum temperatures, evaporation rates, relative humidity, and rainfall during 2018–19 and 2019–20 are shown in

Figure 1.

2.2. Significance of Variation Sources

The genotypes used in the present study along with pedigree details are given in

Table 1. Dissecting of total variability into its components revealed that the first main effect component i.e., genotype effect is highly significant for all the agro-morphological (germination %, 60 days tiller, 90 days tiller, 120 days tiller, plant height, cane diameter, number of malleable canes, cane yield) and quality (juice weight, juice extraction, brix value, pol %, purity %, single cane weight, fibre content) parameters (

Table 2). However, out of five physiological parameters only two parameters i.e., nitrogen balance index and chlorophyll content exhibited highly significant genotypic effect, whereas, remaining three parameters i.e., flavonoid content, anthocyanin content and leaf area does not shown any significant differences among the studied traits. The other main effect i.e., year effect is only significant for six traits (germination %, 60 days tiller, 90 days tiller, 120 days tiller, pol% and fibre content) and the remaining 14 traits exhibited no significant differences among the studied genotypes. The interaction component (genotype × year) effect was found to be significant only for 90 days tiller, 120 days tiller and fibre content, whereas the remaining 17 studied traits does not exhibit any significant differences among genotypes with respect to genotype × year effect.

2.3. Mean Performance of Agro-Morphological, Quality and Physiological Traits

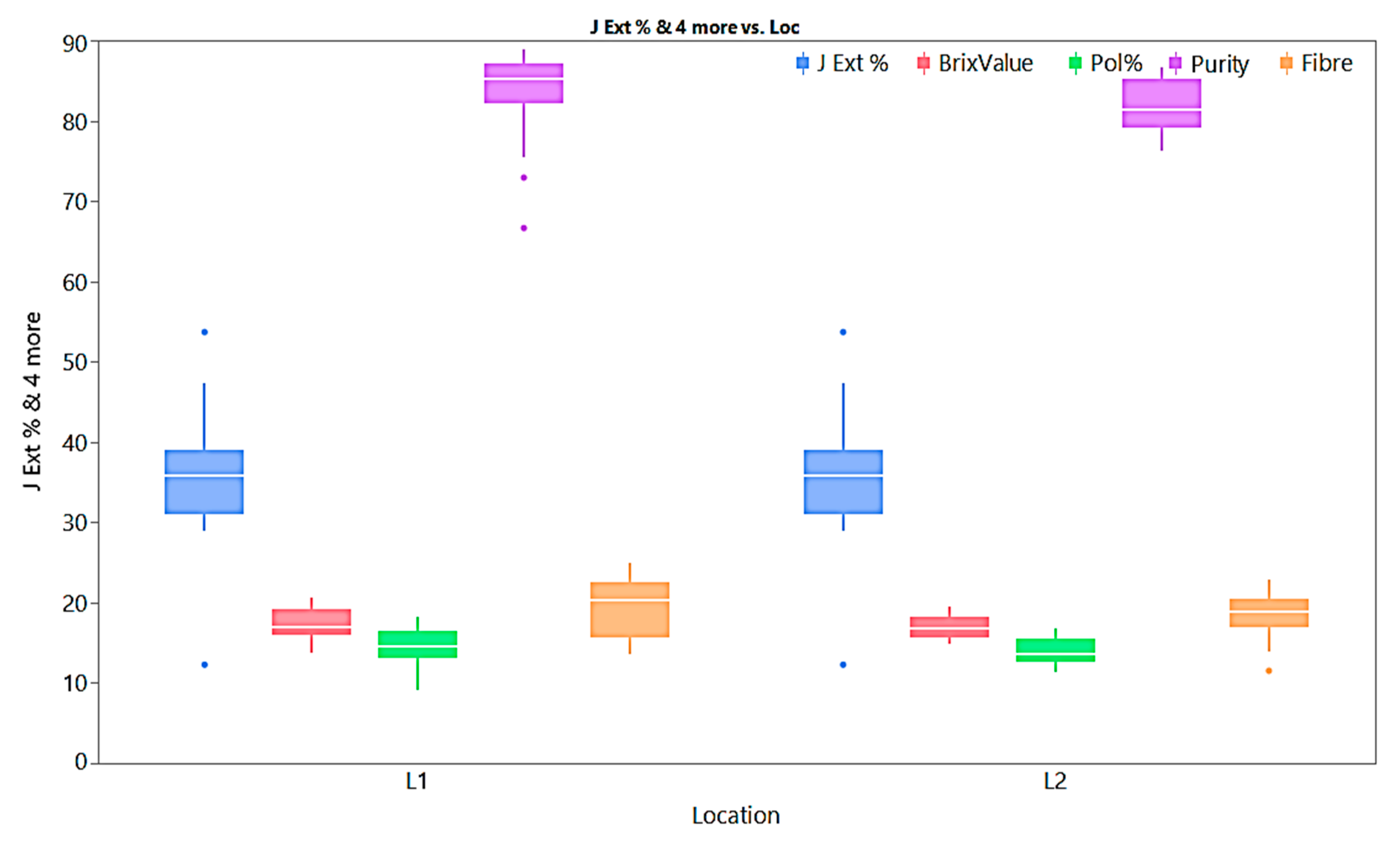

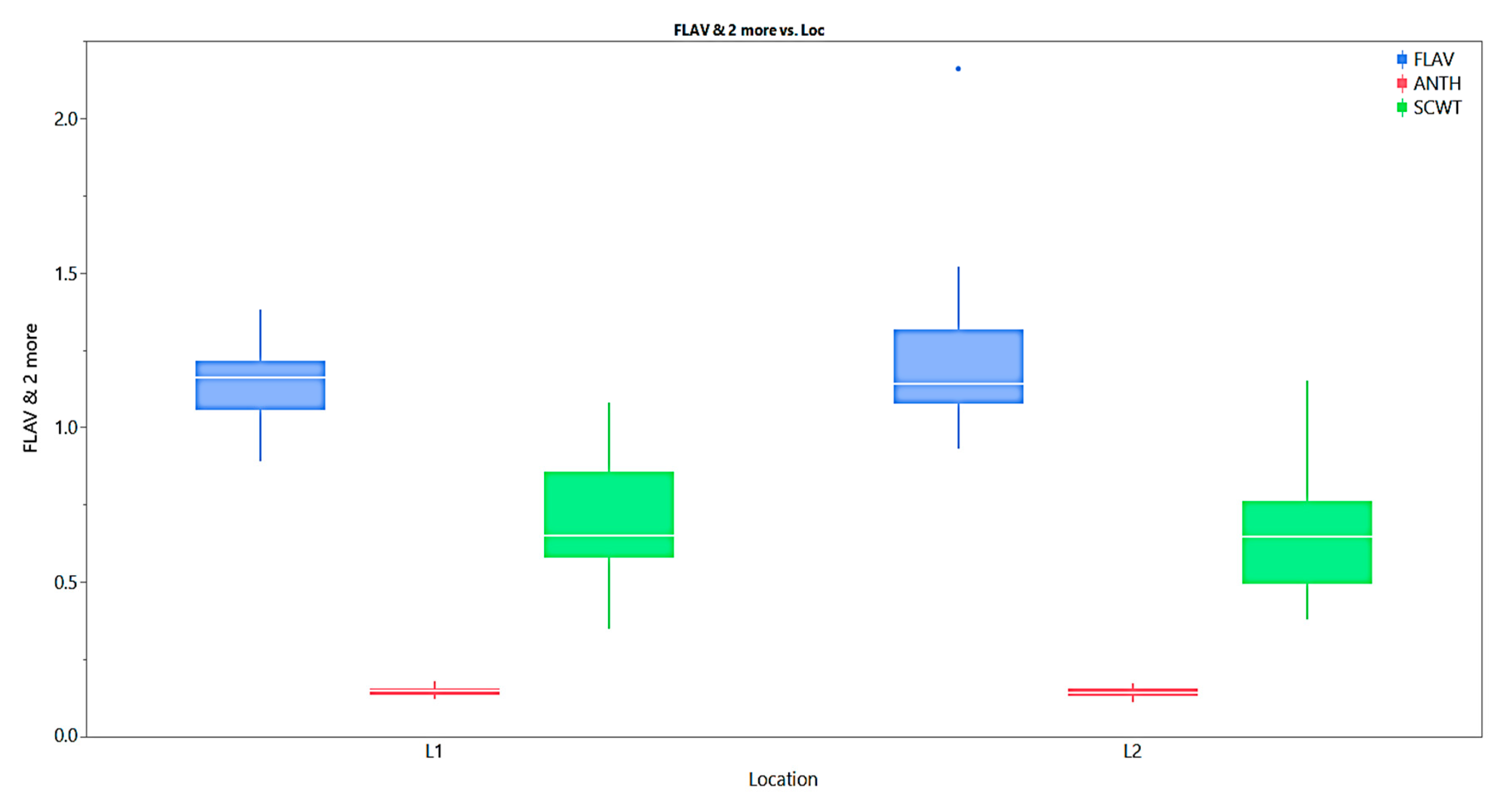

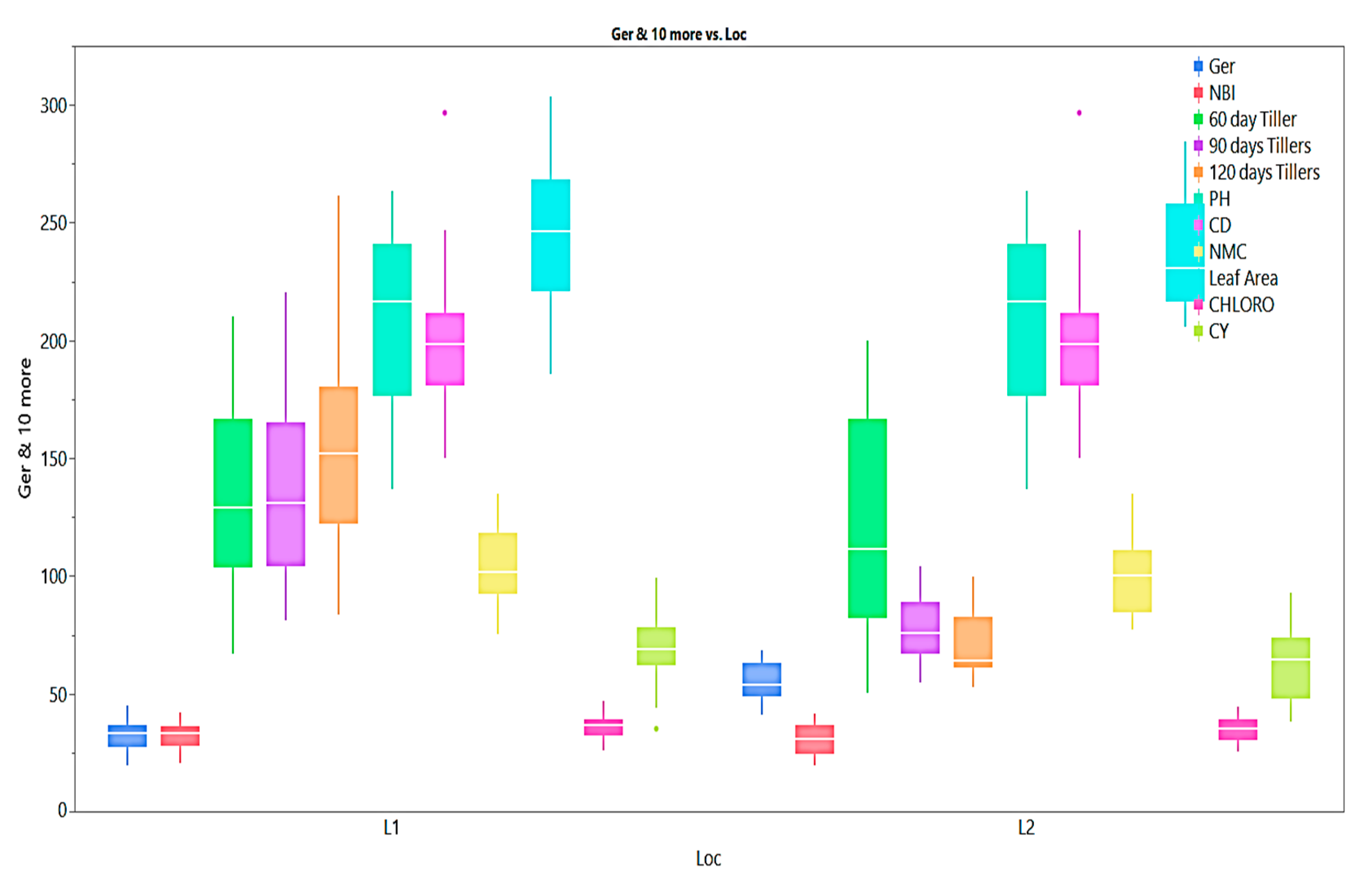

The mean performance of agro-morphological, quality and physiological parameters is illustrated as box plots in

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4. Although all the studied traits were influenced by the environment, the magnitude of environmental effect is higher for agro-morphological traits compared to quality and physiological traits. The magnitude of variation for the number of tillers at 60 days is more than that of 90 days and 120 days. The mean germination percentage is also highly influenced by the environmental effect. Generally, the crop year 2018-19 is more favorable for all the studied traits except germination percentage and flavonoid content than the crop year 2019-20 as the trait's performance measured by percent superiority ranged from 1.8 to 54.7. A few traits also exhibited extreme genotypes for juice extraction %, purity, fibre content, cane diameter, and cane yield as some of the genotypes located outside the error bars (

Figure 2 and

Figure 4).

2.4. Correlation Studies

A correlation analysis was conducted to examine the relationships among the studied traits. The results revealed significant correlations between various variables. The correlation coefficients of agro-morphological, quality and physiological traits are given in

Table 3. Cane yield has a significant positive association with the number of tillers at 60 (0.57) and 90 days (0.39), cane height (0.51), single cane weight (0.84), purity % (0.35), and fibre content (0.35), however, juice weight had a significant negative association. The important quality trait i.e., Pol% had a significant positive correlation with cane diameter, juice weight, juice extraction %, brix value, purity %, single cane weight, and a significant negative association with fibre content, number of malleable canes and nitrogen balance index. The fibre content had a significant association with the maximum number of 14 traits including 7 traits positive (number of tillers at 60, 90 and 120 days, cane height; number of malleable canes, cane yield, nitrogen balance index) and 7 traits with negative association (germination %, cane diameter; juice weight, juice extraction %, brix value; pol%, purity). The other important economic trait juice weight had a significant positive association with cane diameter, juice extraction %, brix value, pol%; purity and single cane weight. Similarly, juice extraction % had a significant positive association with cane diameter and juice weight, brix value, pol%, purity, single cane weight, and significant negative association with fibre content, number of malleable canes, nitrogen balance index, and chlorophyll content.

Physiological traits had fewer significant associations with agro-morphological and quality traits. Out of the studied four physiological traits, nitrogen balance index had significant associations with a maximum of 8 traits including 3 positive (cane height, fibre content, nitrogen balance index) and 5 negative (juice extraction %, brix value, pol%, flavonoid content, and anthocyanin content) associations. Chlorophyll content had a significant positive association (0.84) with the nitrogen balance index and a significant negative association with juice extraction % (-0.37) and purity (-0.36). Anthocyanin content had a significant negative association with nitrogen balance index, chlorophyll content, and a significant positive association with flavonoid content. The physiological trait leaf area does not have a significant association with any of the studied traits. Generally, there is a strong and significant positive association among sugarcane juice quality parameters including juice weight, juice extraction %, brix value, pol%, and purity.

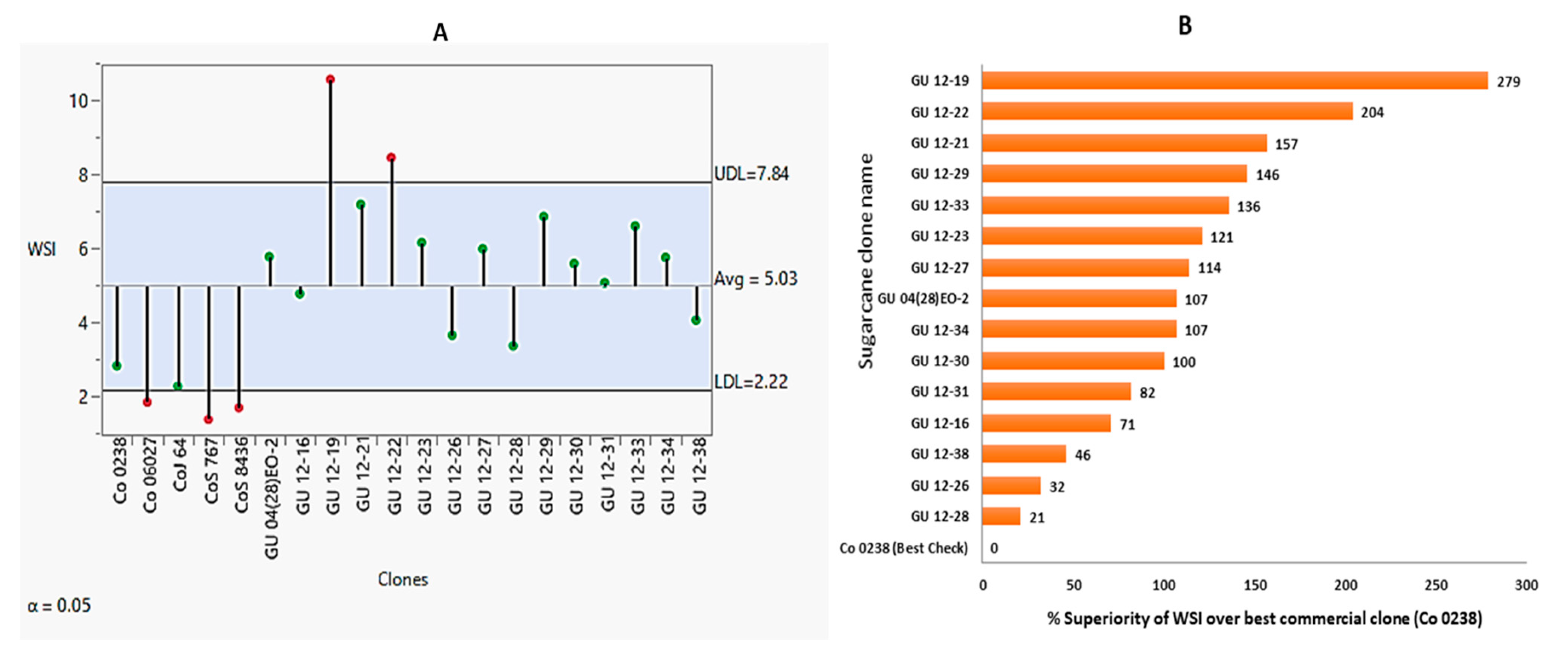

2.5. Winter Sprouting Ability

Winter sprouting ability measured as winter sprouting index (WSI) of

Erinathus procerus hybrids and check clones are presented in

Figure 5A and

Table 4. The WSI of all the check clones is lower than the

E. procerus hybrids. The WSI of commercial check clones range from 1.4 to 2.8. However, in

E. procerus derived hybrids it was ranged from 3.4 to 10.6. Among the check clones, Co 0238 was found to be the best genotype followed by CoJ 64. However, the best genotype (Co 0238) among the check clones is also inferior to the poorest genotype (GU 12-28) among the procerus hybrids. The percent superiority of

E. procerus hybrids over the best commercial check clone (Co 0238) is given in

Figure 5B. GU 12-19 was the best genotype for winter sprouting ability with a WSI of 10.6 and a percent superiority of 279 followed by GU 12-22 (WSI: 8.5 and % superiority over best check was 204), GU 12-21 (WSI: 7.2 and % superiority over best check 157) and GU 12-29 (WSI: 6.9 and % superiority over best check 146). Out of 15 hybrids, nine

E. procerus hybrids had better winter sprouting ability over best check Co 0238 and experimental mean (WSI: 3.8), However, remaining six hybrids had better performance over all the checks and on par performance with mean value as indicated in figure 5A.

2.6. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) – Biplot Analysis

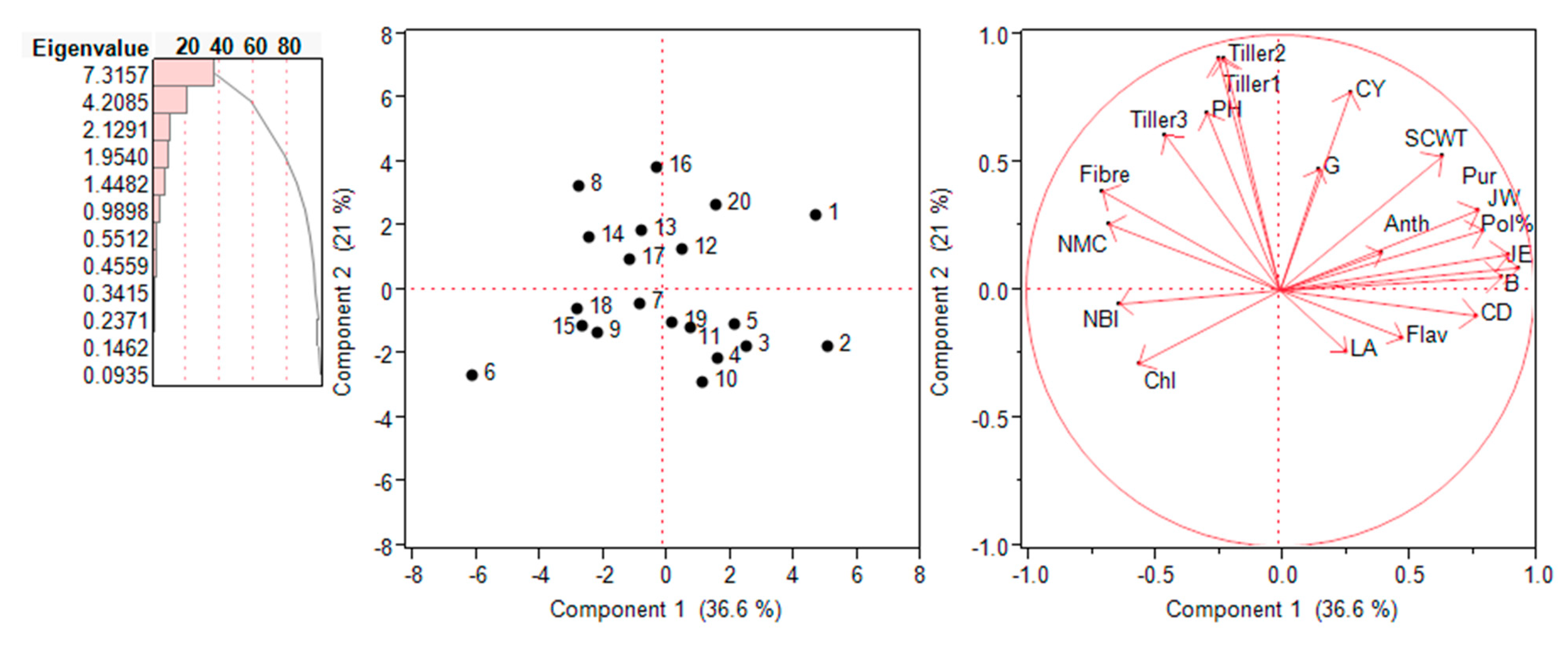

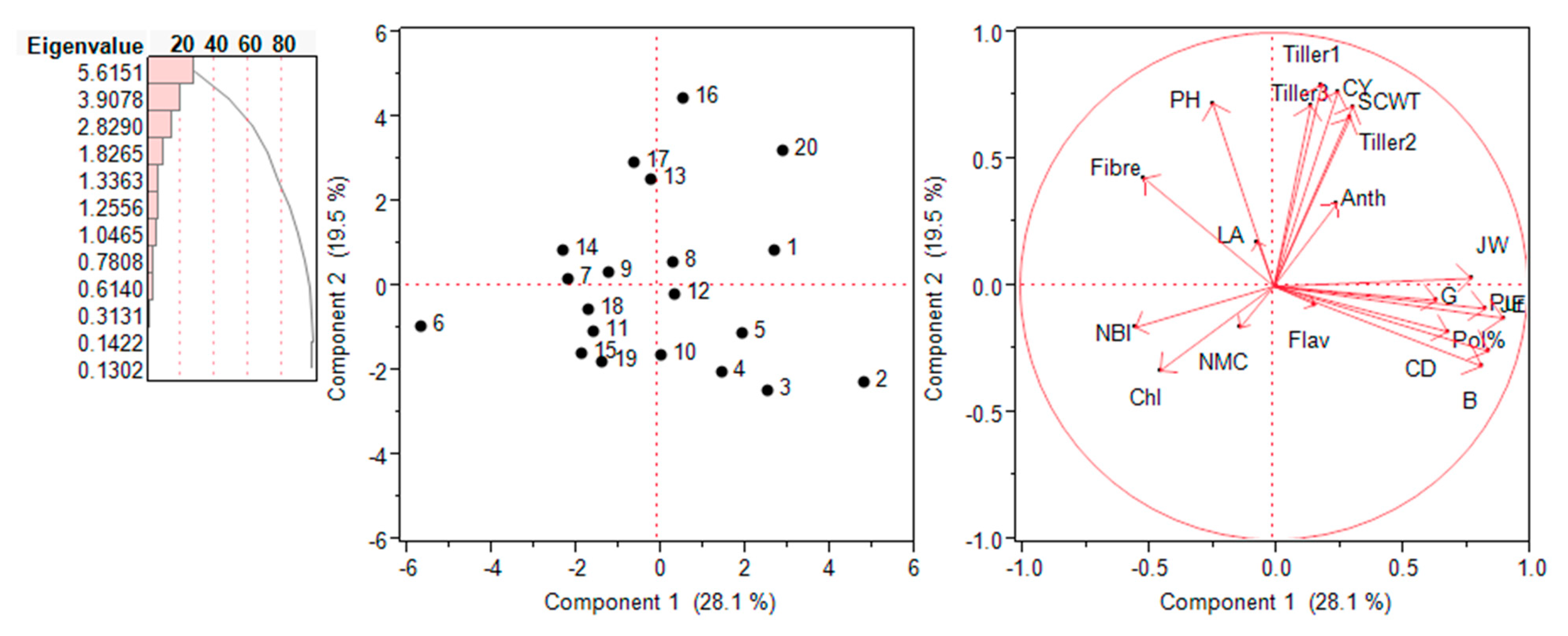

The interrelationship among various traits and genotypes were assessed in the form of biplots in each environment is shown in

Figure 6 and

Figure 7. Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed on the 20 traits measured and all 20 genotypes in both the environments. First two PCA components provided a realistic summary of the data and explained 57.6% of total variation for traits and genotypes. First PCA was most important and attributes to 36.6% of total variation. PCA1 was attributed to Single cane weight, cane yield, pol%, purity, juice extraction%, juice weight, germination% and anthocyanin for largest positive loadings. Tillers numbers, plant height, fibre%, and numbers of millable canes had largest negative loadings. As a results PCA1 distinguished the accessions primarily by the contribution of high value for cane yield, single cane weight, and juice weight. The PCA2 explained the additional 21% of the total variation and was attributed to positive loadings of plant height, tillers numbers, numbers of millable canes and fibre%. Majority of the parameters occupied the right side of the biplot and upper side left.

Through biplot analysis, four kinds of information can be inferred i.e., the relationship among genotypes, trait variability, correlation among traits, and relative value of accession to character. In the year 2018, PC1 and PC2 explained 36.6 and 21.0% of phenotypic variations, respectively. Combining PCA1 and PCA2 accounted total of 57.6% variability. Similarly, in the year 2019, PC1 and PC2 explained 28.1% and 19.5% of phenotypic variation, respectively.

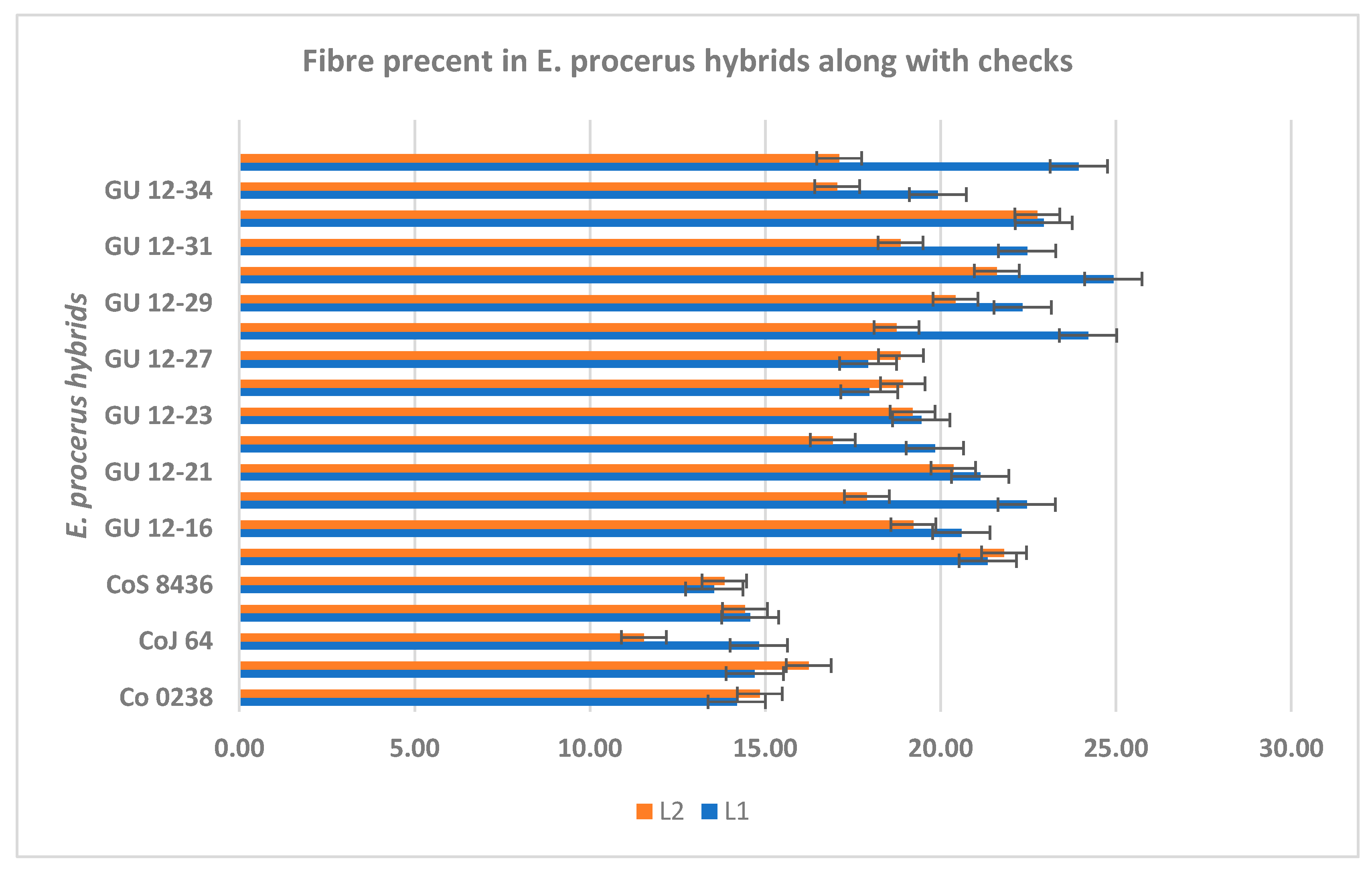

2.7. Exploring Fiber Content in Procerus Hybrids

The fiber percentage and industrial utilization of the procerus hybrids were also assessed. The fiber content varied among the different hybrids. The mean fibre of the trial recorded was 19.66% and 18.43% in plant and ratoon crop respectively. Seven procerus hybrids viz., GU12-30, GU12-28, GU12-38, GU12-33, GU12-19, GU12-31, GU12-29 had >22.0% fibre whereas three hybrids had 20-22% fibre and five hybrids had 15-20% fibre. The similar trend was also observed I ratoon crop. (

Figure 8). A higher fiber percentage was recorded in procerus hybrids .indicating that their proportion of fiber content could be processed to produce fiber suitable for weaving into textiles, such as bags, clothing, and home textiles. These variations indicated that certain canes had a higher proportion of fiber content, making them more suitable for industrial applications [15]. Cane with high fiber content can be utilized in the production of biodegradable materials, such as bioplastics and packaging, offering sustainable alternatives to traditional plastic products.

2.8. Performance for Physiological Traits

The mean flavonoid (FLAV) content of the sugarcane crop in the location (L1) and location (L2) was 1.14 and 1.23 respectively, and the minimum and maximum FLAV in the L1 were 0.89 and 1.38, while the minimum and maximum FLAV in the L2 were 0.93 and 2.16 (Fig) respectively. Among the studied clones, Co J 64 and GU 12-30 were recorded with higher FLAV more than 1.14 in the L1, while GU 12-21, and CoJ 64 indicated better FLAV (>1.23) in the L2. GU-12-19, GU-12-33, and GU-12-19, GU-12-23 were recorded with less Flav in the L1 and L2 respectively. Leaf flavonoids and their importance in sugarcane have been reported by Colombo et al [16].

The mean anthocyanin (ANTH) content of the sugarcane crop in the location (L1) and location (L2) was 0.147 and 0.144 respectively, and the minimum and maximum ANTH in the L1 were 0.123 and 0.179, while the minimum and maximum ANTH in the L2 were 0.111 and 0.172 (Fig) respectively. Among the studied clones, Co 0238 and GU 12-22 were recorded with higher ANTH of more than 0.147 in the L1, while GU 12-30, and GU 12-38 indicated better ANTH (>0.144) in the L2. CoJ 64, GU 04(28) and GU 12-34, Co 0238 were recorded with less Flav in the L1 and L2 respectively. Anthocyanins plays a vital role in cool weather condition and it act as a antioxidant against cold injury and their importance in sugarcane have been reported by Colombo et al. [16]. Anthocyanin accumulation was positively correlated with antioxidant capacity, which potentially protected Tartary buckwheat sprouts from cold stress [17]. Anthocyanins inhibit the production of free radicals and lower the levels of ROS under low temperature stress [18].

2.9. Resistance of Erianthus procerus Hybrids against the Red Rot

A total of fifteen hybrids clones were subjected to the screening process against subtropical and tropical isolated. The results of the screening revealed varying levels of resistance among the tested clones. A high level of resistance (R) to red rot against virulent pathotypes of subtropical (CF08, and CF09) was observed, indicating their ability to withstand infection and exhibit minimal disease symptoms. The clones were classified as moderately resistant (MR), indicating a moderate level of resistance to the pathogen. On the other hand, the clones were categorized as moderately susceptible (MS), indicating a higher susceptibility to red rot compared to the resistant and moderately resistant clones. Last, clones that are classified as susceptible (S) indicate their vulnerability to infection and the development of severe disease symptoms (

Table 5). The red rot rating of the F1 hybrid and BC hybrids against the mixed inoculum of CF671 and CF94012 (

Colletotricum falcatum) is given in the

Table 5. The intergeneric hybrid has shown resistant reaction and the back cross hybrids viz., GU 12-21, GU 12-23, GU 12-29 and GU 12-31 were also resistant and other BC hybrids were moderately resistant.

3. Discussion

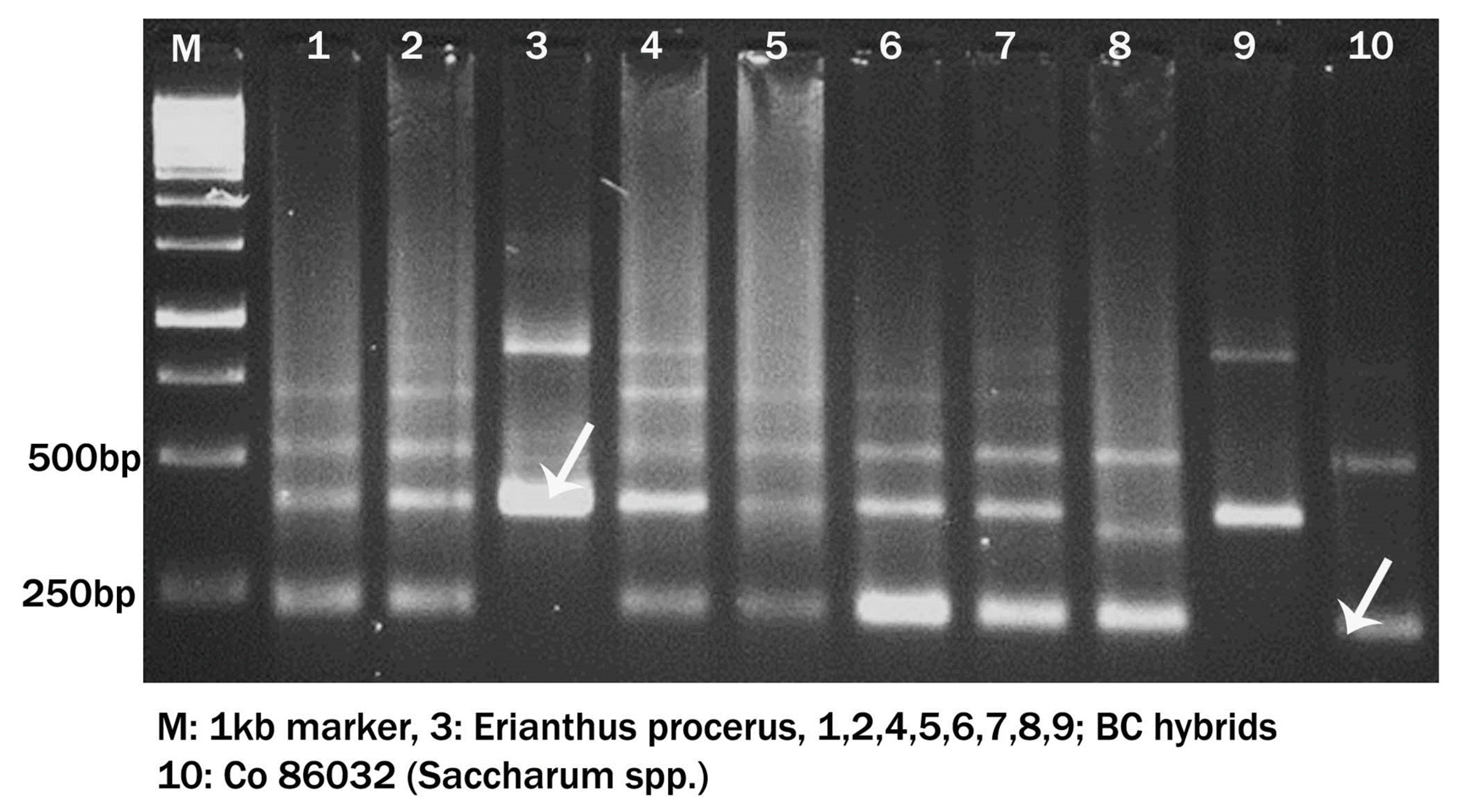

Genetic resources of Erianthus genus consists of seven species, among them two species, E. arundinaceus and E. procerus are the promising. Erianthus gained significant attention of the sugarcane breeders globally as a source for higher tillering, high ratooning ability, high biomass and tolerance against the potential biotic and abiotic stresses [9,12,35]. Erianthus is highly adapted to the varied environments and extensively distributed in both tropical and subtropical region. However, introgression of Erianthus had its own limitation due to its low compatibility, high genetic distance and moreover difficulty in identifying the true hybrids from the selfed one.the work on utilization of Erianthus arundinaceus and its introgression into sugarcane for higher biomass has been successful [19–22]. Similarly utilization of E. procerus in sugarcane breeding was very limited and the work on the intergeneric hybridization between Saccharum and E. procerus had been done at ICAR-Sugarcane Breeding Institute, Coimbatore [17]. The developed intergeneric hybrids were confirmed using 5s rDNA markers which are able to differentiate between Saccharum and Erianthus [7,41,42]. The confirmed true intergeneric hybrids were again backcrossed to Saccharum spp., to recover more of Saccharum genome. A total of fifteen such clones derived from the programme of intergeneric hybridization and backcrossing were evaluated at ICAR-Sugarcane breeding Institute, regional station, Karnal, India, for their agronomic performance, winter rationing ability and reaction against red rot resistance. The genotypic effect for all the agro morphological traits and quality traits were significant indicating the worth of procerus derived breeding lines in commercial breeding programme to improve the economically important traits such as tiller number and plant height, cane diameter, number of millable canes which decides cane yield ultimately. The year effect is significant only for six traits including fibre content and pol % which indicated the inconsistent nature of these traits. The interaction was significant for tillers at 90 days tillers at 120 days and fibre content, indicating selection for these traits should be done cautiously with multi environment testing.

The positive association was observed between cane yield with the number of tillers at 60 and 90 days, cane height, single cane weight and similar results were reported by Parihar 2020, in commercial canes. The procerus hybrids were tall growing but they are thinner than the commercial canes hence in our study diameter not influenced the cane yield. However, juice weight had a significant negative association with cane yield indicating more fiber content in procerus derived clones. It was also concluded that the extraction percent was also negatively associated with fibre content and quality traits pol% and brix were negatively associated with fibre %. Genetic variability of clones for fibre percent and its related traits was observed in E. procerus hybrids as observed by Doule et al. [30]

Winter sprouting ability measured as winter sprouting index (WSI) is very important for cane varieties grown in subtropical regions. Unlike tropical climate, subtropical region faces many climatic vagaries viz., high temperature and water deficit stress during summer and chilling injury-cold stress during winter. The crop is also affected by water logging during rainy season. Sugar mills in the subtropical regions starts cane crushing in mid of November therefore, harvesting of the crop starts from November and continue till January for early crushing periods, this period coincide with peak winter. The harsh winter reduces the crop ratooning ability, due to lack of sprouting in low temperature (4-10°C) and is one of main reasons for low productivity in ratoons of subtropics [23] and farmers are not able to harvest full potential of ratoon crop. The, introgression of cold tolerant genes conferring high ratooning ability from allied genera is a promising alternative to breed the suitable cultivars with better winter ratooning ability. In the present study Erianthus procerus derived hybrids were evaluated for their winter sprouting potential under subtropical climates. The nine procerus hybrids demonstrated notably superior winter sprouting capability compared to the top performing check Co 0238. The genotypes GU 12-19, GU 12-22 and GU 12-21 with superior WSI will definitely serve as an alternate source to introgress the winter sprouting ability in subtropical varieties and enhance the better ratooning ability of commercial clones under cold stress conditions. The earlier study with 632 sugarcane germplasm revealed a significant and positive correlation of winter sprouting index (WSI) with numbers of tillers and millable canes in ratoon crop (Bakshiram et al. [13,46]) It was also reported the highest WSI of 6.5 and in this study five clones had a WSI of more than 6.5 indicating superior winter ratooning ability of E. procerus introgressed hybrids.. This study also further confirms to utilize the WSI to assess the winter ratooning ability of sugarcane clones and identified the noteworthy of procerus hybrids for better ratooning potential [24,25].

The fibre in sugarcane getting important in modern world as source of energy to utilize it in cogeneration, production of second-generation bio ethanol, biogas, pyrolysis to produce bio-oil and biochar [43–45]. In our study seven procerus hybrids recorded more than 22% fibre, indicating that their proportion of fiber content could be processed to produce fiber suitable for weaving into textiles, such as bags, clothing, and home textiles, making them more suitable for industrial applications and bioenergy production [15].

In the study clones, CoJ 64 and GU12-30 exhibited higher flavonoid value exceeding 1.14 in plant while GU 12-21 showed superior flavonoids (>1.23) in ratoon trial. The significance of flavonoids in sugarcane has been previously documented by Colombo et al. [16]. Similarly, hybrids GU12-22 and Co 0238 exhibited higher anthocyanin value exceeding 0.147 in plant trial while GU12-30 and GU12-38 showed better anthocyanin (>0.144) in ratoon trial. The role of anthocyanin accumulation in cool weather is crucial, acting as antioxidants against cold injury. Anthocyanin accumulation is positively correlated with antioxidant capacity, providing protection against cold stress [17]. Anthocyanin also play inhibitory role for production of free radicals and reducing levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) under low-temperature stress [18].

Red rot in sugarcane is the major problem of sugarcane cultivation in subtropics and responsible for loss of several elite varieties from the cultivation (40). In the present study the procerus hybrids were also screened for their reaction against tropical and subtropical races of red rot pathogens. The hybrid GU04 (28) EO-2, and backcrossed hybrids, GU12-19, GU12-21, GU12-22, GU12-23, GU12-26, GU12-27, GU12-30 and GU12-31 were R to MR for the tested races indicating their broad spectrum resistance against red rot. Three clones viz., GU 12-19, GU 12-21 and GU 12-22 had shown both excellent winter ratooning ability and broad spectrum red rot resistance indicating their potential to improve both the traits. Further crossing of GU 12-21 with commercial clones revealed that more than 60% of the progenies were resistant to red rot suggesting the valuable potential of the clones in imparting red rot resistance. Similar findings were also reported in E.arundinaceus introgressed clones with cold tolerance and red rot resistance (Ram et al 2001). The E.procerus derived hybrids proved to be the wealthiest pre-bred lines, which can be utilized in sugarcane improvement programme. Their high biomass nature, high tillering ability, winter sprouting ability, high fibre content and red rot resistance give new hopes to further enhance the winter ratooning ability and red rot resistance in commercial sugarcane varieties with broadened genetic base.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experimental Site

The experiment was conducted at the ICAR-Sugarcane Breeding Institute, Regional Centre, Karnal (Haryana) India, site is located in 29.1°–29.5° N and 76.3°–77.1° E in a subtropical climate with an elevation of 243 m above mean sea level and an average annual rainfall of approximately 744 mm. In summer, the maximum temperature ranges from 34–45 °C, while in winter, the minimum temperature ranges from 5–8 °C. The soil in this area varies from clay-loamy to loam, with a pH range of 8.0–8.5.

4.2. Plant Material and Experimental Design

A total of fifteen clones of

E. procerus derived hybrids were evaluated along with five standard sugarcane varieties, i.e.

, Co 0238, CoJ 64, CoS 8436 CoS 767 and Co 06027 for their cane yield parameter, physiological traits and winter sprouting potential. List of the

E. procerus hybrids along with their parentages is provided in the

Table 1). The date of planting for the plant crop was in the first week of March during 2018-19 crop season, and harvested during March-April, 2019-20. Similarly, the ratoon crop was raised in 2019-20 during the spring season (Feb-March). The experiment was carried out over a span of two years (2018–19 and 2019–20 spring seasons) and three seasons for WSI using a randomized block design with three replications. Plots utilized had dimensions of 2 m × 3 m and were spaced 0.9 m apart. Standard recommended practices were followed for crop production. Three lifesaving irrigations were applied at the time of germination, tillering and grand growth stage of the crop; otherwise, the crop was managed upon natural rainfall throughout the year. The observations were collected from each plot, specifically for the number of tillers and numbers of millable canes (NMC), brix% in cane, single cane weight (SCW), cane height, Juice quality parameters [31,36] and physiological parameter like chlorophyll content, Nitrogen balance index (NBI), flavonoid and anthocyanin content were recorded from 10-month-old crop. Five randomly selected canes from each plot were tagged and assessed for the estimation of fiber percentage, 250 g subsamples of shredded canes were crushed in a rapipol machine and subsequently oven dried. The fresh and dry weights of these samples were recorded. Fiber percentage was determined using rapipol extraction method, as outlined by Thangavelu and Rao [32].

in the given context, A represents the dry weight of bagasse (residue) plus the bag after the drying process (measured in grams). B represents the dry weight of the bag alone (measured in grams). C represents the fresh weight of the cane (measured in grams).

To study the winter sprouting capability of these clones, the stalks of plant crops was cut at ground level in three replications during the last week of December 2018, aligning with the peak winter period. This specific block of three replications was designated for observing the winter-initiated ratoon crop.

The winter sprouting index (WSI) was worked out following the formula suggested by Ram et al., [13] as follows:

Based on WSI, sugarcane genotypes are classified into four categories as shown below.

WSI Sprouting category

3.00 and above Excellent winter sprouting

2.01 to 2.99 Good winter sprouting

0.10 to 2.00 Poor winter sprouting

< 0.10 Low temperature sensitive (LTS) clones

To compute the fresh biomass yield (measured in tons per hectare, t/ha), the formula used was fresh biomass yield =.

4.3. Red Rot Evaluation

To assess their resistance to red rot, a comprehensive screening process was conducted on all procerus hybrids. This study aimed to evaluate their resistance against the predominant and highly virulent pathotypes of red rot, Colletotrichum falcatum specifically the CF 08 and CF 09 in subtropical and cf671 and cf671+cf94012 in tropical [33,39]. The screening was performed under field conditions. To initiate the screening, a mixed inoculum containing both races of Colletotrichum falcatum was prepared. This inoculum was then applied to the sugarcane plants through plug and nodal methods. The screening was conducted when the crops were approximately seven months old, with inoculation occurring in September.

4.4. SPAD Reading

SPAD (soil plant analysis development) meter was used to estimate the non-destructive chlorophyll content of leaf by measuring the transmission of red light and infrared light at 660 nm and 940 nm, respectively. The data recorded were then got converted into a digital signal [34]. Nitrogen balance index (NBI), Flavonoid and anthocyanin content was observed from top visual dewlap (TVD) of three different plants.

4.5. Confirmation of Intergeneric Hybrids

Erianthus-specific markers were developed from 5S rRNA spacer regions using sequence tagged PCR.

Erianthus procerus clone along with randomly selected intergenic hybrids and

Saccharum spp. hybrid Co 86032 (commercial variety) were screened with primers that amplify 5S rDNA regions in the genome to identify

Erianthus-specific fragments (

Figure 9). PCR amplification conditions for 5 s rDNA of D’Hont et al. [7] were followed. Amplified products were resolved on 2% agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide and documented using a gel documentation system (Syngene, USA).

4.6. Statistical Analysis

The collected data underwent analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests for statistical evaluation [37]. The statistical package SAS 9.3 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, USA) was utilized to calculate means, standard deviations, and coefficients of variance for various traits [38]. A correlation diagram exhibiting the correlation between the studied parameters along with the p-value was shown through R software version 4.1.3.

5. Conclusions

The study concludes that Erianthus procerus hybrid had demonstrated commendable resilience, better winter sprouting potential than the popular check varieties of subtropical regions, allowing to thrive in diverse climatic conditions and environments. Its robust growth and adaptability enable it to withstand various stress factors, including drought, pests, and diseases tolerance. Selection of clones with high WSI combining red rot resistance, could serves as an effective measure for identifying desired clones with low-temperature tolerance in subtropical climate. We suggest to use this criteria into sugarcane selection programme so that potential clones with better ratooning potential can be identified under subtropical climate and evaluated further for their quality and cane yielding parameters. Additionally, these identified clones can serve as donor parents in sugarcane hybridization programme along with existing cultivars to sustain the sugar industry in northern India.

Author Contributions

MRM and KMR conceived and designed the experiments. MRM, RK, NK, KMR & MLC laid out the trials and collected the data. AKR, HKMS, GRK, GH, PG, SA, MRK and MRM processed and analyzed the data. All authors discussed, edited the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the ICAR-Sugarcane Breeding Institute, Coimbatore, India.

Data availability statement

All data supporting the conclusions of this manuscript are provided within the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the Director, ICAR-Sugarcane Breeding Institute, Coimbatore-07, Tamil Nadu, India for providing necessary facilities and financial support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Manochio, C.; Andrade, B.R.; Rodriguez, R.P.; Moraes, B.S. Ethanol from biomass: A comparative overview. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 80, 743–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Day, D.F.L. Composition of sugarcane, energy cane, and sweet sorghum suitable for ethanol production at Louisiana sugar mills. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 38, 803–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatwachirawong, P.; Thumkrasair, S.; Srisink, S. Sugarcane Breeding. Final Report: Research Development Design and Engineering Project BT-B-01-PG-11-4924. NSTDA. 2009, Pathum Thani, Thailand.

- Cursi,D. E.; Hoffmann, H.P.; Barbosa, G.V.S.; Bressiani, J.A.; Gazaffi, R.; Chapola, R.G.; Fernandes, J.A.R.; Balsalobre, T.W.A.; Diniz, C.A. Santos JM: History and current status of sugarcane breeding, germplasm development and molecular genetics in Brazil. Sugar Tech. 2022, 24, 112–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindaraj, P.; Amalraj, V.A.; Mohanraj, K.; Nair, N.V. Collection, characterization and phenotypic diversity of Saccharum spontaneum L. from arid and semiarid zones of northwestern India. Sugar Tech. 2014, 16, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.K. Origin and distribution of Saccharum Bot. Gaz. 1957, 119, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'hont, A.; Rao, P.; Feldmann, P.; Grivet, L.; Islam-Faridi, N.; et al. Identification and characterization of sugarcane intergeneric hybrids, Saccharum officinarum × Erianthus arundinaceus, with molecular markers and DNA in situ hybridization. TheorAppl Genet. 1995, 91, 320–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Q.; Aitken, K.; Deng, H.; Chen, X.W.; Fu, C.; Jackson, P.A.; McIntyre, C.L. Verification of the introgression of Erianthus arundinaceus germplasm into sugarcane using molecular markers. Pl. Breeding. 2005, 124, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuhara, S.; Terajima, Y.; Irei, S.; Sakaigaichi, T.; Ujihara, K. Identification and characterization of intergeneric hybrid of commercial sugarcane (Saccharum spp. hybrid) and Erianthus arundinaceus (Retz.) Jeswiet. Euphytica 2013, 189, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanraj, K.; Nair, N.V. Biomass potential of novel interspecific hybrids involving improved clones of Saccharum. Ind. Crops Prod. 2014, 53, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amalraj, V.A.; Balasundaram, N. On the taxonomy of the members of ‘Saccharum complex’. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2006, 53, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, N.V.; Mohanraj, K.; Sunadaravelpandian, K.; Suganya, A.; Selvi, A.; Appunu, C. Characterization of an intergeneric hybrid of Erianthus procerus × Saccharum officinarum and its backcross progenies. Euphytica. 2017, 213–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakshi, R.; Karuppaiyan, R.; Meena, M.R.; Kumar, R.; Kulshreshtha, N. Winter Sprouting Index of Sugarcane Genotypes Is a Measure of Winter Ratooning Ability. Int. J. Dev. Res. 2017, 7, 15385–15391. [Google Scholar]

- Verma, R.S. Sugarcane Ratoon Management. International Book Distributing Co., Lucknow. 2002, 266p.

- Hoang, N.V.; Furtado, A.; Botha, F.C.; Simmons, B.A.; Henry, R.J. Potential for genetic improvement of sugarcane as a source of biomass for biofuels. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2015, 3, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colombo, R.; Lanças, F.M.; Yariwake, J.H. Determination of flavonoids in cultivated sugarcane leaves, bagasse, juice and in transgenic sugarcane by liquid chromatography-UV detection. Journal of Chromatography A 2006, 1103, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.J.; Bai, Y.C.; Li, C.L.; Yao, H.P.; Chen, H.; Zhao, H.X.; Wu, Q. Anthocyanins accumulate in tartary buckwheat (Fagopyrum tataricum) sprout in response to cold stress. Acta Physiologiae Plantarum. 2015, 37, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.Q.; Yang, L.T.; Li, Y.R. Physiological and biochemical characteristics related to cold resistance in sugarcane. Sugar Technology. 2015, 17, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindaraj, P. SBIEC 14006—A high biomass energycane for power, alcohol and paper industries. J. Sugarcane Res. 2020, 10, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandel, R.; Yang, X.; Song, J.; Wang, J. Potentials, challenges, and genetic and genomic resources for sugarcane biomass improvement. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, M.R.; Kumar, R.; Ramaiyan, K. Biomass potential of novel interspecific and intergeneric hybrids of Saccharum grown in subtropical climates. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 21560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medeiros, K.L.S.; Reis, V.R.; Santos, J.R.M. Evaluation of biomass productivity and energy potential of energy cane varieties in Brazil. Ind Crops Prod. 2019, 140, 111625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, R.; Shrivastava, A.K.; Solomon, S.; Yadav, R.L. Low temperature stress-induced biochemical changes affect bud sprouting in sugarcane (Saccharum spp. hybrid). Plant Growth Regulation. 2007, 53, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan, R. Red rot of sugarcane (Colletotrichum falcatum Went) CAB Reviews. 2021, 16, 23–57. [Google Scholar]

- Mohanraj, K.S.A. Broadening the genetic base of sugarcane: introgression of red rot resistance from the wild relative Erianthus procerus. In Proceedings of XII International Society of Sugar Cane Technologists Pathology Workshop. 2018, September 03-07, Vol -18, ICAR-SBI, Coimbatore.

- Hale, A.L.; Dufrene, E.O.; Tew, T.L.; Pan, Y.B.; Viator, R.P.; White, P.M.; Veremis, J.C.; White, W.H.; Cobill, R.; Richard, E.P. Registration of ‘Ho 02-113’ sugarcane. J. Plant Regist. 2013, 7, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahi, B.K.; Ram, B.; Kumar, P. Evaluation of sugarcane clones for ratoonability during winter month. Indian J. Sugarcane Technol. 2002, 17, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Ram, B.; Sahi, B.K.; Hemaprabha, G.; Kumar, P. Effect of ratooning during winter and spring on selection in sugarcane seedling. Indian J. Sugarcane Technol. 2005, 20, 52–56. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Kumar, D. Correlation and Path Coefficient Analysis in Sugarcane Germplasm under Subtropics. African J. Agri. Res. 2014, 9, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doule, R.B.; Balasundaram, N. Genetic variability in fiber and related characters for selection of sugarcane. Sugar Tech. 2004, 6, 73–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.C.P. & C.C.C. Cane Sugar Handbook. 1993, Wiley.

- Thangavelu, S.C.R.K. Comparison of Rapi pol extractor and Cutex cane shredder methods for direct determination of fiber in Saccharum clones. Proc. Annu. Conv. Sugar Technol. Assoc. India. 1982, 46, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan, K.V.B.N.R. Red rot of sugarcane – Criteria for grading resistance. J. Indian Bio Soc. 1961, 40, 566–577. [Google Scholar]

- Arun kumar, R.; Vasantha, S.; Tayade, A.S.; Anusha, S.; Geetha, P.; Hemaprabha, G. Physiological Efficiency of Sugarcane Clones Under Water-Limited Conditions. Trans. ASABE, 2020, 63, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemaprabha, G. Sugarcane Varieties for Abiotic Stress Tolerance. In Training manual on “Sugarcane Cultivation in Biotic and Abiotic Stress Conditions”; Nair, V., Gopalasundaram, P., Shanty, T.R.; Prathap, P.D.; Eds.; ICAR-Sugarcane Breeding Institute—641 007: Tamil Nadu, India, 2008.

- Meade, G.P.; Chen, J.C.P. Cane Sugar Hand Book, 10th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez, K.A.; Gomez, A.A. Statistical Procedures for Agricultural Research; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1984.

- SAS Institute. The SAS System for Windows, Release 9.3; SAS Institute: Independence, KS, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Babu, C.; Koodalingam, K.; Natarajan, U.; Shanthi, R.; Govindaraj, P. Genetic enhancement of sugarcane (Saccharum sp. hybrids) for resistance to red rot disease and economic traits. J. Agric. Sci. 2010, 4, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan, R. Severe Red Rot Epidemics in Sugarcane in Sub-tropical India: Role of Aerial Spread of the Pathogen. Sugar Tech 2023, 25, 1275–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachakkil, B.; Terajima, Y.; Ohmido, N.; et al. Cytogenetic and agronomic characterization of intergeneric hybrids between Saccharum spp. hybrid and Erianthus arundinaceus. Sci Rep. 2019, 9, 1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobhakumari, V.P.; Mohanraj, K.; Nair, N.V.; Mahadevaswamy, H.K. ; Bakshi Ram, Cytogenetic and Molecular Approaches to Detect Alien Chromosome Introgression and Its Impact in Three Successive Generations of Erianthus procerus × Saccharum. CYTOLOGIA 2020, 85, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckeridge, M.S.; De Souza, A.P.; Tavares, E.Q.P.; Cambler, A.B. Sugarcane cell wall structure and degradation: From monosaccharide analyses to the glycomic code. Advances of Basic Science for Second Generation Bioethanol from Sugarcane, Springer International Publishing; Jan 1, 2017, 7-19.

- Carvalho-Netto, O.V.; Bressiani, J.A.; Soriano, H.L.; Fiori, C.S.; Santos, J.M.; Barbosa, G.V.; et al. The potential of the energy cane as the main biomass crop for the cellulosic industry [Internet]. Springer International Publishing; Dec 21, 2014, 20. Available from: http://www.chembioagro.

- Dias, M.O.S.; Junqueira, T.L.; Cavalett, O.; Cunha, M.P.; Jesus, C.D.F.; Rossell, C.E.V.; et al. Integrated versus stand-alone second generation ethanol production from sugarcane bagasse and trash. Bioresour Technol. 2012, 103, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, B.; Sreenivasan, T.; Sahi, B.; et al. Introgression of low temperature tolerance and red rot resistance from Erianthus in sugarcane. Euphytica 2001, 122, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

The weather parameters of crop growing years 2018-19 and 2019-20.

Figure 1.

The weather parameters of crop growing years 2018-19 and 2019-20.

Figure 2.

Box plots for juice extraction %, Brix value, Pol %, Purity, and Fibre content of E. procerus hybrids and check varieties.

Figure 2.

Box plots for juice extraction %, Brix value, Pol %, Purity, and Fibre content of E. procerus hybrids and check varieties.

Figure 3.

Box plots for Flavanoid content, Anthocyanin content and Single cane weight of E. procerus hybrids and check varieties.

Figure 3.

Box plots for Flavanoid content, Anthocyanin content and Single cane weight of E. procerus hybrids and check varieties.

Figure 4.

Box plots for Agro-morphological, quality and physiological traits of E. procerus hybrids and check varieties.

Figure 4.

Box plots for Agro-morphological, quality and physiological traits of E. procerus hybrids and check varieties.

Figure 5.

Winter sprout potential of E. procerus and commercial clones. (A): Mean of 3 years (2018–2019, 2019–2020, and 2020–21) per se performance of the clones (B): Mean of three years (2018–2019, 2019–2020 and 2020–21) percent superiority of E Procerus hybrids over best commercial clone.

Figure 5.

Winter sprout potential of E. procerus and commercial clones. (A): Mean of 3 years (2018–2019, 2019–2020, and 2020–21) per se performance of the clones (B): Mean of three years (2018–2019, 2019–2020 and 2020–21) percent superiority of E Procerus hybrids over best commercial clone.

Figure 6.

Loading plots of PCA1 and PCA2 for E. procerus hybrids during the year 2018. Chl: chlorophyll; LA: leaf area; Flav: flavonoids; NBI: nitrogen balance index; CY: cane yield: SCWT: single cane weight; G: germination; CD: cane diameter; B: Brix % in Juice; JE: juice extraction; PH: plant height; JW: juice weight; Pur: purity.

Figure 6.

Loading plots of PCA1 and PCA2 for E. procerus hybrids during the year 2018. Chl: chlorophyll; LA: leaf area; Flav: flavonoids; NBI: nitrogen balance index; CY: cane yield: SCWT: single cane weight; G: germination; CD: cane diameter; B: Brix % in Juice; JE: juice extraction; PH: plant height; JW: juice weight; Pur: purity.

Figure 7.

Loading plots of PCA1 and PCA2 for E. procerus hybrids during the year 2019. Chl: chlorophyll; LA: leaf area; Flav: flavonoids; NBI: nitrogen balance index; CY: cane yield: SCWT: single cane weight; G: germination; CD: cane diameter; B: Brix % in Juice; JE: juice extraction; PH: plant height; JW: juice weight; Pur: purity.

Figure 7.

Loading plots of PCA1 and PCA2 for E. procerus hybrids during the year 2019. Chl: chlorophyll; LA: leaf area; Flav: flavonoids; NBI: nitrogen balance index; CY: cane yield: SCWT: single cane weight; G: germination; CD: cane diameter; B: Brix % in Juice; JE: juice extraction; PH: plant height; JW: juice weight; Pur: purity.

Figure 8.

Fibre percent in Erianthus procerus hybrids along with checks.

Figure 8.

Fibre percent in Erianthus procerus hybrids along with checks.

Figure 9.

Confirmation of Erianthus procerus hybrids using 5S r DNA Marker.

Figure 9.

Confirmation of Erianthus procerus hybrids using 5S r DNA Marker.

Table 1.

Parentage of Erianthus procerus derived hybrids and check varieties used in the study.

Table 1.

Parentage of Erianthus procerus derived hybrids and check varieties used in the study.

| SN |

Clone |

Generation |

Female |

Male |

Remarks |

| 1 |

GU 04(28) EO-2 |

F1 |

IND 90-776 |

PIO 96-435 |

GU 04 (28) EO-2 is an intergeneric hybrid between Erianthus procerus and S. officinarum

|

| 2 |

GU 12-16 |

BC1 |

GU 04(28) EO-2 |

Co 06027 |

BC 1 hybrid |

| 3 |

GU 12-19 |

BC1 |

GU 04(28) EO-2 |

Co 06027 |

BC 1 hybrid |

| 4 |

GU 12- 21 |

BC1 |

GU 04(28) EO-2 |

Co 06027 |

BC 1 hybrid |

| 5 |

GU 12-22 |

BC1 |

GU 04(28) EO-2 |

Co 06027 |

BC 1 hybrid |

| 6 |

GU 12- 23 |

BC1 |

GU 04(28) EO-2 |

Co 06027 |

BC 1 hybrid |

| 7 |

GU 12-26 |

BC1 |

GU 04(28) EO-2 |

Co 06027 |

BC 1 hybrid |

| 8 |

GU 12-27 |

BC1 |

GU 04(28) EO-2 |

Co 06027 |

BC 1 hybrid |

| 9 |

GU 12- 28 |

BC1 |

GU 04(28) EO-2 |

Co 06027 |

BC 1 hybrid |

| 10 |

GU 12- 29 |

BC1 |

GU 04(28) EO-2 |

Co 06027 |

BC 1 hybrid |

| 11 |

GU 12-30 |

BC1 |

GU 04(28) EO-2 |

Co 06027 |

BC 1 hybrid |

| 12 |

GU 12- 31 |

BC1 |

GU 04(28) EO-2 |

Co 06027 |

BC 1 hybrid |

| 13 |

GU 12-33 |

BC1 |

GU 04(28) EO-2 |

Co 06027 |

BC 1 hybrid |

| 14 |

GU 12-34 |

BC1 |

GU 04(28) EO-2 |

Co 06027 |

BC 1 hybrid |

| 15 |

GU 12-38 |

BC1 |

GU 04(28) EO-2 |

Co 06027 |

BC 1 hybrid |

| 16 |

Co 06027 |

- |

CoC 671 |

IG 91-1100 |

Commercial Variety Tropical |

| 17 |

Co 0238 |

- |

Co LK 8102 |

Co 775 |

Commercial Variety Sub Tropical |

| 18 |

CoJ 64 |

- |

Co 976 |

Co 617 |

Commercial Variety Sub Tropical |

| 19 |

CoS 767 |

- |

Co 419 |

Co 319 |

Commercial Variety Sub Tropical |

| 20 |

CoS 8436 |

- |

MS 68/47 |

Co 1148 |

Commercial Variety Sub Tropical |

Table 2.

Significance level (p value) of variation sources.

Table 2.

Significance level (p value) of variation sources.

| Traits |

Main effects |

Interaction Effects |

Genotypes

(19) |

Years

(1) |

Genotypes × Years

(19) |

| Germination |

0.0145* |

< 0.0001* |

0.3211 |

| 60 days Tiller |

< 0.0001* |

0.1845 |

0.9997 |

| 90 days Tiller |

< 0.0001* |

< 0.0001* |

0.0003* |

| 120 days Tiller |

0.0005* |

< 0.0001* |

0.0034* |

| Plant Height |

< 0.0001* |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| Cane diameter |

< 0.0001* |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| Juice weight |

< 0.0001* |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| Juice extraction % |

< 0.0001* |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| Brix Value |

< 0.0001* |

0.0755 |

0.8373 |

| Pol % |

< 0.0001* |

0.0272* |

0.5523 |

| Purity % |

< 0.0001* |

0.0969 |

0.4001 |

| Single cane weight |

< 0.0001* |

0.6407 |

0.3455 |

| Fibre content |

< 0.0001* |

0.0142* |

0.0076* |

| Number of millable canes |

< 0.0244* |

0.4372 |

0.9871 |

| Cane Yield t/ha |

< 0.0001* |

0.1095 |

0.9913 |

| Nitrogen Balance Index |

< 0.0001* |

0.1433 |

0.4334 |

| Chlorophyll |

< 0.0001* |

0.2199 |

0.5204 |

| Flavonoid |

0.1072 |

0.1474 |

0.3385 |

| Anthocyanin |

0.2709 |

0.4417 |

0.5011 |

| Leaf Area |

0.7480 |

0.6119 |

0.9852 |

Table 3.

Correlation matrix among cane growth parameters and physiological traits.

Table 3.

Correlation matrix among cane growth parameters and physiological traits.

| |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

16 |

17 |

18 |

19 |

20 |

| 1 |

1.00 |

0.066 |

-0.45** |

-0.59** |

-0.01 |

0.12 |

0.17 |

0.21 |

0.17 |

0.06 |

0.05 |

-0.00 |

-0.37* |

-0.10 |

-0.08 |

-0.20 |

-0.17 |

0.23 |

-0.13 |

-0.18 |

| 2 |

|

1.00 |

0.57** |

0.40* |

0.66** |

-0.28 |

0.06 |

-0.09 |

-0.02 |

0.02 |

0.12 |

0.45** |

0.32* |

0.04 |

0.57** |

-0.04 |

-0.18 |

-0.24 |

0.02 |

-0.05 |

| 3 |

|

|

1.00 |

0.88** |

0.29 |

-0.15 |

0.00 |

-0.03 |

0.07 |

0.122 |

0.215 |

0.149 |

0.356* |

0.295 |

0.395* |

0.054 |

-0.090 |

-0.168 |

0.121 |

-0.007 |

| 4 |

|

|

|

1.00 |

0.207 |

-0.19 |

-0.09 |

-0.14 |

0.02 |

0.03 |

0.01 |

0.00 |

0.33* |

0.32* |

0.23 |

0.14 |

0.08 |

-0.21 |

0.11 |

-0.08 |

| 5 |

|

|

|

|

1.00 |

-0.14 |

0.13 |

-0.27 |

-0.31* |

-0.20 |

-0.09 |

0.43** |

0.43** |

-0.01 |

0.51** |

0.32* |

0.26 |

-0.25 |

-0.02 |

-0.22 |

| 6 |

|

|

|

|

|

1.00 |

0.85** |

0.81** |

0.50** |

0.51** |

0.47** |

0.28 |

-0.41** |

-0.18 |

0.20 |

-0.20 |

-0.17 |

0.09 |

0.12 |

0.16 |

| 7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1.00 |

0.86** |

0.66** |

0.67** |

0.58** |

0.50** |

-0.34* |

-0.27 |

-0.36* |

-0.19 |

-0.15 |

0.00 |

0.07 |

0.08 |

| 8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1.00 |

0.77** |

0.79** |

0.70** |

0.44** |

-0.50** |

-0.32* |

0.27 |

-0.40* |

-0.37* |

0.12 |

0.17 |

0.12 |

| 9 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1.00 |

0.97** |

0.77* |

0.29 |

-0.57** |

-0.37* |

0.07 |

-0.35* |

-0.27 |

0.09 |

0.09 |

0.06 |

| 10 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

11.00 |

0.89** |

0.34* |

-0.54** |

-0.34* |

0.17 |

-0.35* |

-0.31 |

0.09 |

0.14 |

0.09 |

| 11 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1.00 |

0.40* |

-0.36* |

-0.21 |

0.35* |

-0.29 |

-0.36* |

0.08 |

0.021 |

0.13 |

| 12 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1.00 |

0.123 |

-0.53** |

0.84** |

-0.26 |

-0.29 |

-0.00 |

0.33* |

0.07 |

| 13 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1.00 |

0.35* |

0.35* |

0.34* |

0.19 |

-0.23 |

-0.10 |

0.08 |

| 14 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1.00 |

-0.01 |

0.26 |

0.04 |

0.00 |

-0.12 |

-0.11 |

| 15 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1.00 |

-0.10 |

-0.27 |

-0.01 |

0.24 |

0.05 |

| 16 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1.00 |

0.84** |

-0.47** |

-0.57** |

-0.01 |

| 17 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1.00 |

-0.19 |

-0.52** |

0.02 |

| 18 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1.00 |

0.31* |

-0.09 |

| 19 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1.00 |

-0.15 |

| 20 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1.00 |

Table 4.

Winter Sprouting Index (WSI) of Erianthus procerus and commercial checks during 2018-19, 2019-20 and 2020-21.

Table 4.

Winter Sprouting Index (WSI) of Erianthus procerus and commercial checks during 2018-19, 2019-20 and 2020-21.

| SN |

Genotype |

Winter Sprouting Index (WSI) |

| 2018-2019 |

2019-20 |

2020-21 |

Mean |

| 1 |

GU 12-19 |

8.0 |

12.2 |

11.6 |

10.6 |

| 2 |

GU 12-22 |

6.1 |

9.9 |

9.5 |

8.5 |

| 3 |

GU 12-21 |

5.3 |

7.2 |

9.1 |

7.2 |

| 4 |

GU 12-29 |

3.5 |

8.8 |

8.4 |

6.9 |

| 5 |

GU 12-33 |

4.0 |

8.6 |

7.3 |

6.6 |

| 6 |

GU 12-23 |

4.8 |

7.3 |

6.4 |

6.2 |

| 7 |

GU 12-27 |

3.9 |

8.7 |

5.5 |

6.0 |

| 8 |

GU 12-34 |

4.2 |

6.9 |

6.3 |

5.8 |

| 9 |

GU 04(28)EO-2 |

6.0 |

6.0 |

5.3 |

5.8 |

| 10 |

GU 12-30 |

5.0 |

5.4 |

6.5 |

5.6 |

| 11 |

GU 12-31 |

3.1 |

5.3 |

6.9 |

5.1 |

| 12 |

GU 12-16 |

3.7 |

5.5 |

5.3 |

4.8 |

| 13 |

GU 12-38 |

2.5 |

4.1 |

5.7 |

4.1 |

| 14 |

GU 12-26 |

2.9 |

4.2 |

3.9 |

3.7 |

| 15 |

GU 12-28 |

2.9 |

4.0 |

3.3 |

3.4 |

| 16 |

Co 0238 (Check) |

2.4 |

3.6 |

2.5 |

2.8 |

| 17 |

CoJ 64 (Check) |

1.7 |

2.9 |

2.3 |

2.3 |

| 18 |

Co 06027 (Check) |

0.5 |

3.1 |

2.0 |

1.9 |

| 19 |

CoS 8436 (Check) |

1.0 |

2.5 |

1.7 |

1.7 |

| 20 |

CoS 767 (Check) |

0.9 |

1.9 |

1.4 |

1.4 |

Table 5.

Reaction of E. procerus clones for red rot pathotypes of tropical (Coimbatore) and subtropical clones during 2018–19 and 2019–20.

Table 5.

Reaction of E. procerus clones for red rot pathotypes of tropical (Coimbatore) and subtropical clones during 2018–19 and 2019–20.

| E. procerus |

2018-19 and 2019-20 |

2018-19 and 2019-20 |

| Coimbatore (Tropical races) |

Karnal (subtropical races) |

| Clones name |

Cf671 |

Cf671+94012 |

Cf08 |

Cf09 |

| GU04 (28) EO-2 |

R |

R |

MR |

MR |

| GU12-16 |

MR |

R |

S |

MR |

| GU12-19 |

R |

MR |

MR |

MR |

| GU12-21 |

R |

R |

MR |

R |

| GU12-22 |

MR |

MR |

MR |

MR |

| GU12-23 |

MR |

R |

- |

MS |

| GU12-26 |

MR |

MR |

MR |

MR |

| GU12-27 |

MR |

R |

MR |

R |

| GU12-28 |

MR |

MR |

S |

MR |

| GU12-29 |

MR |

R |

S |

MR |

| GU12-30 |

MR |

MR |

MR |

MR |

| GU12-31 |

MR |

R |

MR |

MR |

| GU12-33 |

R |

MR |

MS |

MR |

| GU12-34 |

R |

MR |

MS |

S |

| GU12-38 |

S |

HS |

S |

S |

| Co 06027 |

MR |

S |

S |

MR |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).