Submitted:

19 December 2023

Posted:

20 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients and study design

2.2. Statistical analyses

3. Results

3.1. Clinical and laboratory features of anti-MDA5+-patients

3.2. Basic laboratory data, anti-SAE antibodies, anti-Ro52 antibodies and the mortality

3.3. Subgroup analysis: Stratification by the positivity of anti-SAE antibodies

| Anti-SAE positive (N=32) | Anti-SAE negative(N=39) | |||||||

| RP-ILD(N=9, 28.1%) | Non-RP-ILD (N=23, 71.9%) |

p-value | OR*** (C.I.#) |

RP-ILD(N=23, 59%) | Non-RP-ILD(N=16, 41%) | p-value | OR***(C.I.#) | |

| LDH (SD**) U/L | 376.22(112.3) | 353.9((135.6) | 0.670 | 0.441(p=0.442,0.057-3.421) | 456.43(230.4) | 439.94(165.1) | 0.807 | 3.385(p=0.55, 0.279-41.087) |

| CRP (S.D.**) mg/dl | 8.23(8.9) | 2.547(3.7) | 0.018* | 2.667(p=0.427, 0.521-13.655) |

5.40(8.04) | 2.26(5.9) | 0.192 | 17.111((p=0.04,1.832-159.802*) |

| Albumin (S.D.**), g/dl | 3.31(1.1) | 3.67(0.75) | 0.358 | 1.905(p=0.659, 0.321-11.312) |

3.05(0.8) | 3.33(0.5) | 0.352 | 1.583(p=0.634, 0.23-10.904) |

| CEA (S.D.**), ng/ml | 11.45(9.6) | 5.15(4.7) | 0.116 | 3(p=0.505, 0.14-64.262) |

13.02((8.4) | 2.67(1.6) | 0.012* |

35(p=0.026, 1.743-702.993*) |

| Ferritin (S.D.**) ng/ml | 2581.25(2103.6) | 557.32(343.2) | 0.004* | 0.597(p=1.00, 0.773-1.087) |

2423.49(2215.2) | 851.15(1137.4) | 0.186 |

19(p=0.032, 1.146-314.971*) |

| CK (SD**), U/L | 157.29(99.6) | 1068.7(3395.8) | 0.49 | 0.489(p=0.662, 0.76-3.145) |

620.86(972.5) | 1492.6(2436.2) | 0.144 | 0.791( p=0.749, 0.211-2.972) |

| AST (SD**) U/L | 48.38(38.1) | 65.86(103.1) | 0.647 | 1.067(p=0.647, 0.161-7.056) |

118.43(143.2) | 58.19(38.8) | 0.111 | 2.411(p=0.209, 0.652-8.92) |

| Myoglobulin (SD**), ng/ml | 92.5(130.8) | 183.68(123.4) | 0.423 | 0.25(p=0.524, 0.07-8.56) |

6(66.7%) | 3(33.3%) | 0.439 | 0.667(p=0.646, 0.047-9.472) |

| ESR (S.D.**) mm/hr | 48.14((29.8) | 47.3(37.8) | 0.958 | 1.333(p=0.546, 0.235-7.556) |

58.25(39.8) | 42.38(30.4) | 0.231 | 1.333(p=0.465, 0.235-7.556) |

| IgE (S.D.**) KU/L | 468.96(567.1) | 155.72(117.2) | 0.215 | 0.75(p=0.652, 0.064-8.834) |

212.1(179.7) | 252.91(215.8) | 0.756 | 0.75(p=0.721, 0.064-8.834) |

| anti-Ro52 antibodies (+) | 2(22.2%) | 7(77.8%) | - | 0.653(p=0.501, 0.107-3.971) |

2(22.2%) | 7(77.8%) | - | 0.653(p=0.179, 0.107-3.971) |

| Smoking | 2(22.2%) | 7(77.8%) | - | 0.653(p=0.501, 0.107-3.971) |

2(22.2%) | 7(77.8%) | - | 0.653(p=0.415, 0.107-3.971) |

| Anti-SAE positive | Anti-SAE negative | |||||||

| Mortality(N=3,9.4%) | Non-Mortality (N=29,90.6%) |

p-value | LR (C.I.) |

Mortality(N=14,35.9%) | Non-Mortality (N=25,64.1%) |

p-value | LR (C.I.) |

|

| RPILD | 3(33.3%) | 6(66.7%) | - |

8.455(p=0.004* 0.101-0.422) |

14(60.9%) | 9(39.1%) | - |

20.131(p<0.001, 0.213-0.607*) |

| LDH (S.D. **) U/L | 392.67(183.8) | 19(86.4%) | 0.656 | 1.311(p=0.252 0.645-0.972) |

402.92(245.9) | 402.92(163.4) | 0.054 | 2.906(p=0.088 0.752-1.018) |

| CRP (S.D.**) mg/dl | 11.68(7.4) | 3.42(5.6) | 0.025* |

4.493(p=0.034* 0.292-0.678) |

8.16(9.4) | 1.84(4.7) | 0.008* |

8.236(p=0.04 0.52-0.89*) |

| Albumin (S.D.**) g/dl | 2.4(0.529) | 3.73(0.8) | 0.007* |

5.194(p=0.023* 0.221-0.657) |

2.62(0.4) | 3.54(0.6) | 0.000* |

8.388(p=0.004* 0.455-0.919) |

| CEA (S.D.**) ng/ml | 11.95(12.4) | 6.12(5.8) | 0.272 | 1.827(p=0.177 0.351-345.1) |

16.5(8.2) | 4.19(4) | 0.002* |

7.664(p=0.06* 0.132-0.84) |

| Ferritin (S.D.**) ng/ml | 3038.33(2320.3) | 607.53(375.1) | 0.001* | 0.43(p=0.512 0.789-1.08) |

3208.14(2200.4) | 696.04(789) | 0.002* |

5.868(p=0.015* 0.467-0.905) |

| CK (SD**) U/L | 91.33(45.8) | 925.04(3104) | 0.651 | 3.394(p=0.065 0.375-1.783) |

754((1175.3) | 1129.9(2054.4) | 0.549 | 1.463(p=0.226, 0.586-9.291)) |

| AST (SD**, U/L | 53.67(64.6) | 61.88(92.9) | 0.884 | 0.145(p=0.704 0.128-21.732) |

119.5(83.5) | 79.28(129.8) | 0.304 |

8.289(p=0.004* 1.648-49.137) |

| Myoglobulin (SD**), ng/ml | 124.3(120.3) | 183.9(110.4) | 0.184 | 2.969(p=0.085 0.028-1.997) |

512.34(723.1) | 1133.4(1219.3) | 0.279 | 0.034(p=0.853 0.118-13.24) |

| ESR (S.D.**) mm/hr | 86.5(3.5) | 44.4(34.9) | 0.106 | 2.776(p=0.096 0.319-1.722) |

57.08(35.6) | 49.1(37.9) | 0.556 | 0.075(p=0.784, 0.278-5.454) |

| IgE (S.D.**) KU/L | 1053.5(369.8) | 130.24(106.6) | 0.000* | 2.055(p=0.152 0.15-0.455) |

127.36(149.8) | 303.12(172.6) | 0.108 | 2.284(p=0.131, 0.008-2.181) |

| anti-Ro52 antibodies (+) | 0(0%) | 9(100%) | - | 2.1(p=0.147 0.54-3.88) |

0(0%) | 9(100%) | - | 2.076(p=0.15, 0.642-12.926) |

| Smoking (+) | 1(11.1%) | 8(88.9%) | - | 0.043(p=0.836 0.104-16.55) |

1(11.1%) | 8(88.9%) | - | 1.949(p=0.163, 0.026-2.269) |

3.4. Subgroup analysis: Stratification by the diagonosis of DM or not

| Non-DM with anti-MDA5 | DM with anti-MDA5 | p-value | |

| Age, y/o | 64.7 (13.9) | 62.4 (13.9) | 0.480 |

| AST (S.D.) U/L | 63.83 (89.1) | 91.64 (116.6) | 0.287 |

| LDH (S.D.) U/L | 344.16 (133.9)) | 468.43 (194.7) | 0.04* |

| Myoglobulin (S.D.), ng/ml | 212.67 (163.4) | 729.59 (981.5) | 0.223 |

| CRP (S.D.) mg/dl | 4.19 (6.9) | 4.15 (6.8) | 0.981 |

| ESR (S.D.) mm/hr | 51.12 (37.6) | 49.1 (35.0) | 0.833 |

| Ferritin (S.D.) ng/ml | 959.89 (1427.2) | 2179.56 (2054.8) | 0.033* |

| CA-153 (S.D.), U/ml | 21.4 (26.3) | 19.08 (12.9) | 0.826 |

| CEA (S.D.) ng/ml | 7.75 (6.47) | 7.78 (8.1) | 0.99 |

| IgE (S.D.) KU/L | 296.5 (369.7) | 208.9 (192.2) | 0.524 |

| Alb (S.D.) g/dl | 3.46 (0.82) | 3.22 (0.76) | 0.278 |

| CK (S.D.) U/L | 755.8 (2839) | 1039.2 (1772.1) | 0.657 |

| Anti-RO52 antibody | 8 (26.7%) | 22 (73.3%) | 0.009* |

| Anti-SAE antibody | 24 (75%) | 8 (25%) | <0.001* |

| RPILD | 11 (33.3%) | 22 (66.7%) | 0.094 |

| Mortality# | 3 (17.6%) | 14(82.4%) | 0.012* |

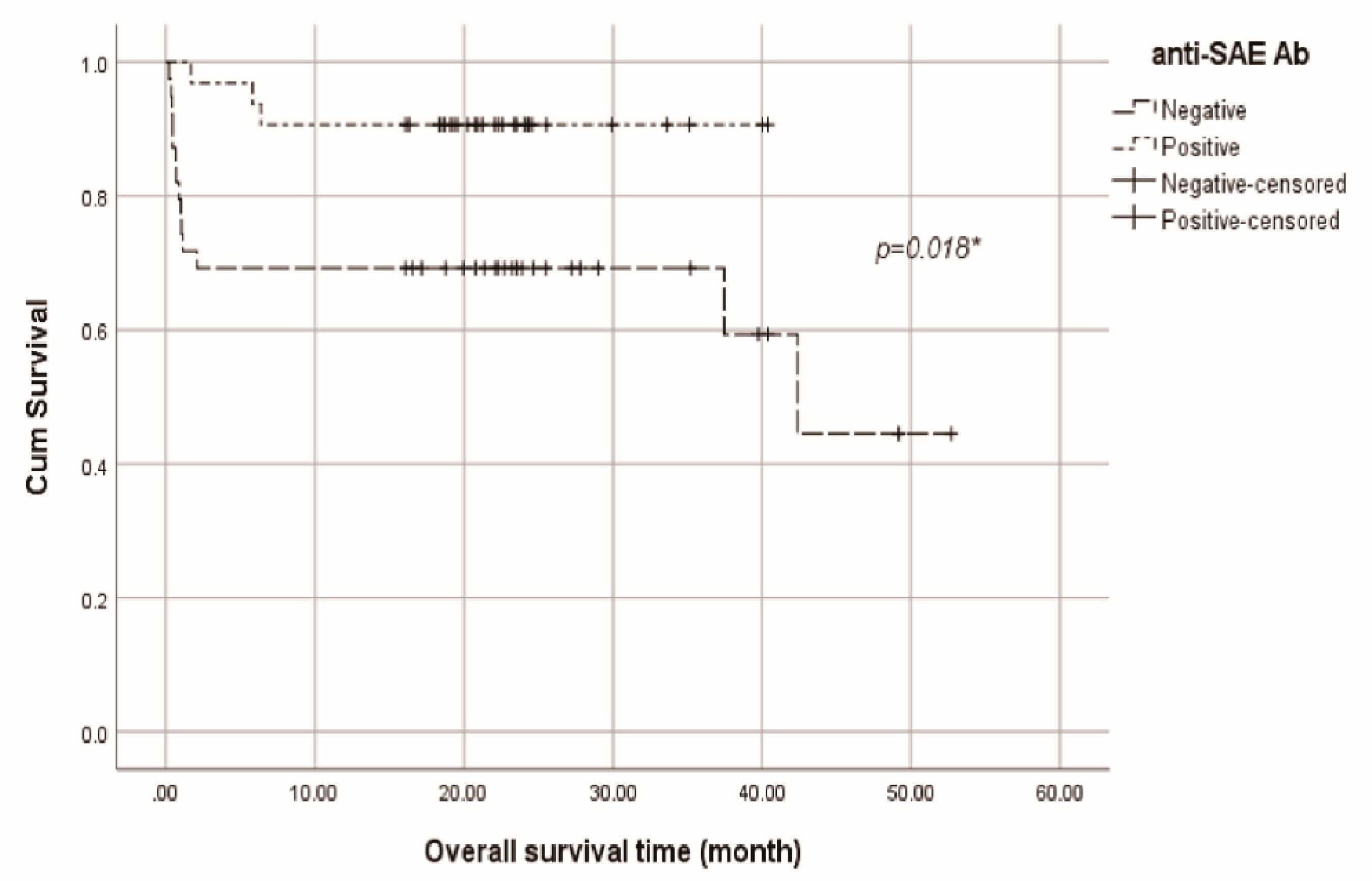

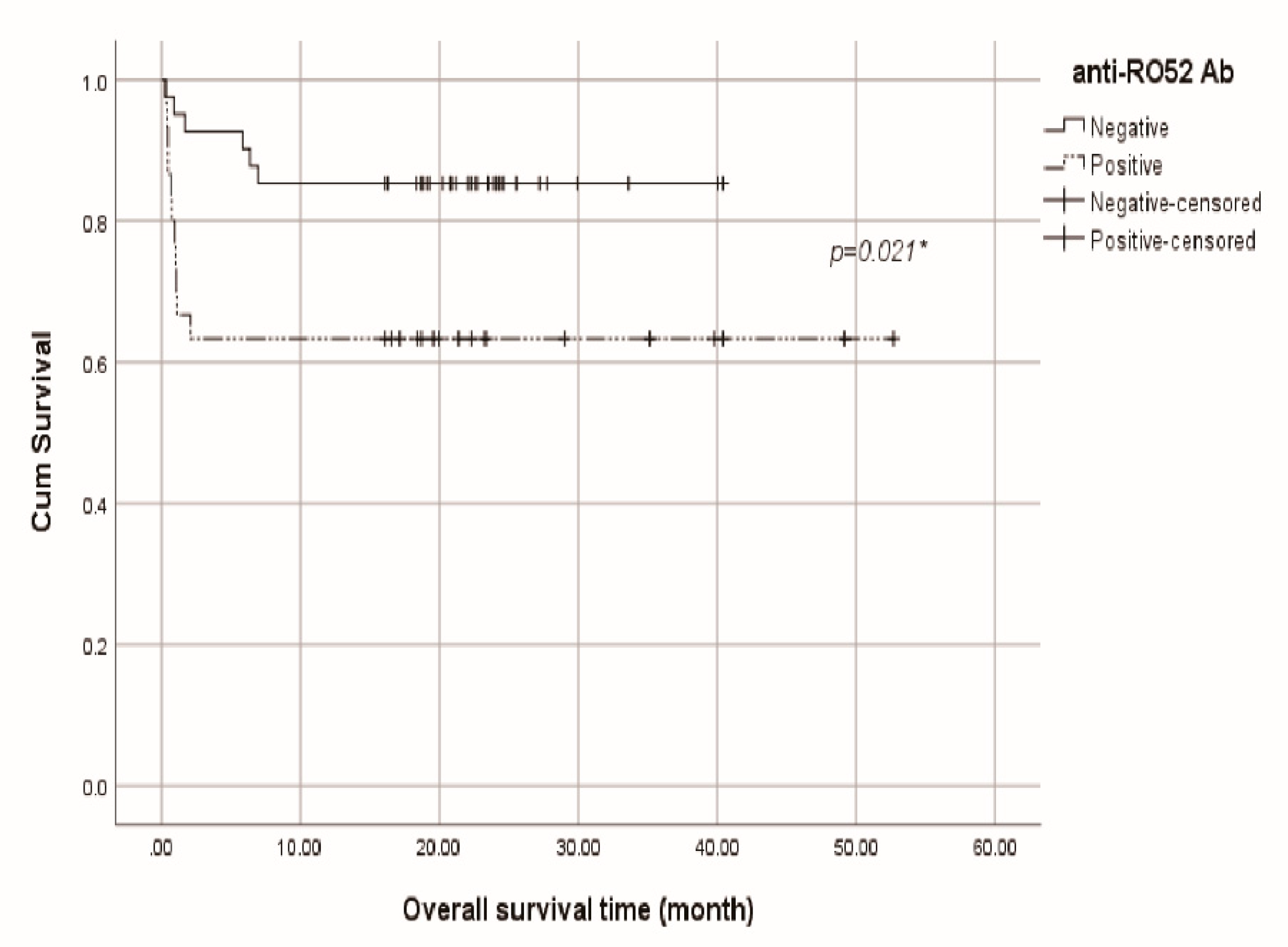

3.5. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of total anti-MDA5 cohort, anti-SAE+ and anti-Ro52+ groups

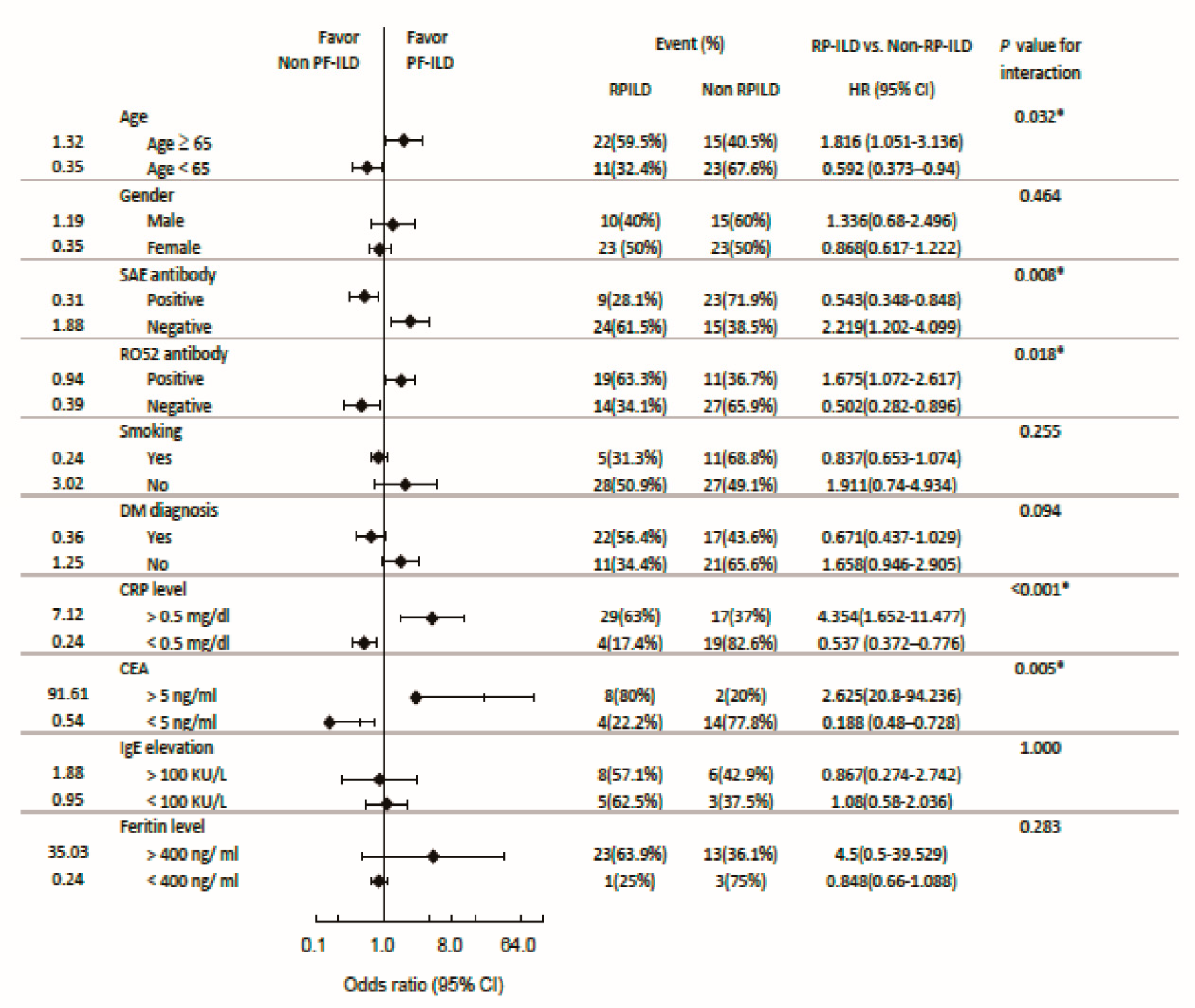

3.6. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses for risk factors of RPILD in anti-MDA5+ patients

| Variable | Univariate | Multivariate | ||||||

| OR | 95% CI of OR | P value | OR | 95% CI of OR | P value | |||

| Female | 1.500 | 0.559-4.025 | 0.421 | 0.494 | 0.057-4.311 | 0.523 | ||

| High AST* | 2.267 | 0.850-6.045 | 0.102 | 3.858 | 0.493-3-.172 | 0.198 | ||

| High LDH** | 1.609 | 0.351-7.377 | 0.54 | 0.254 | 0.01-6.357 | 0.404 | ||

| High Ferritin*** | 5.308 | 0.5-56.391 | 0.166 | 10.713 | 0368-312.028 | 0.168 | ||

| Ro52 | 3.331 | 1.245-8.91 | 0.017§ | 2.198 | 0.116-41.489 | 0.599 | ||

| SAE | 0.245 | 0.9-0.668 | 0.006§ | 0.058 | 0.004-0.829 | 0.036§ | ||

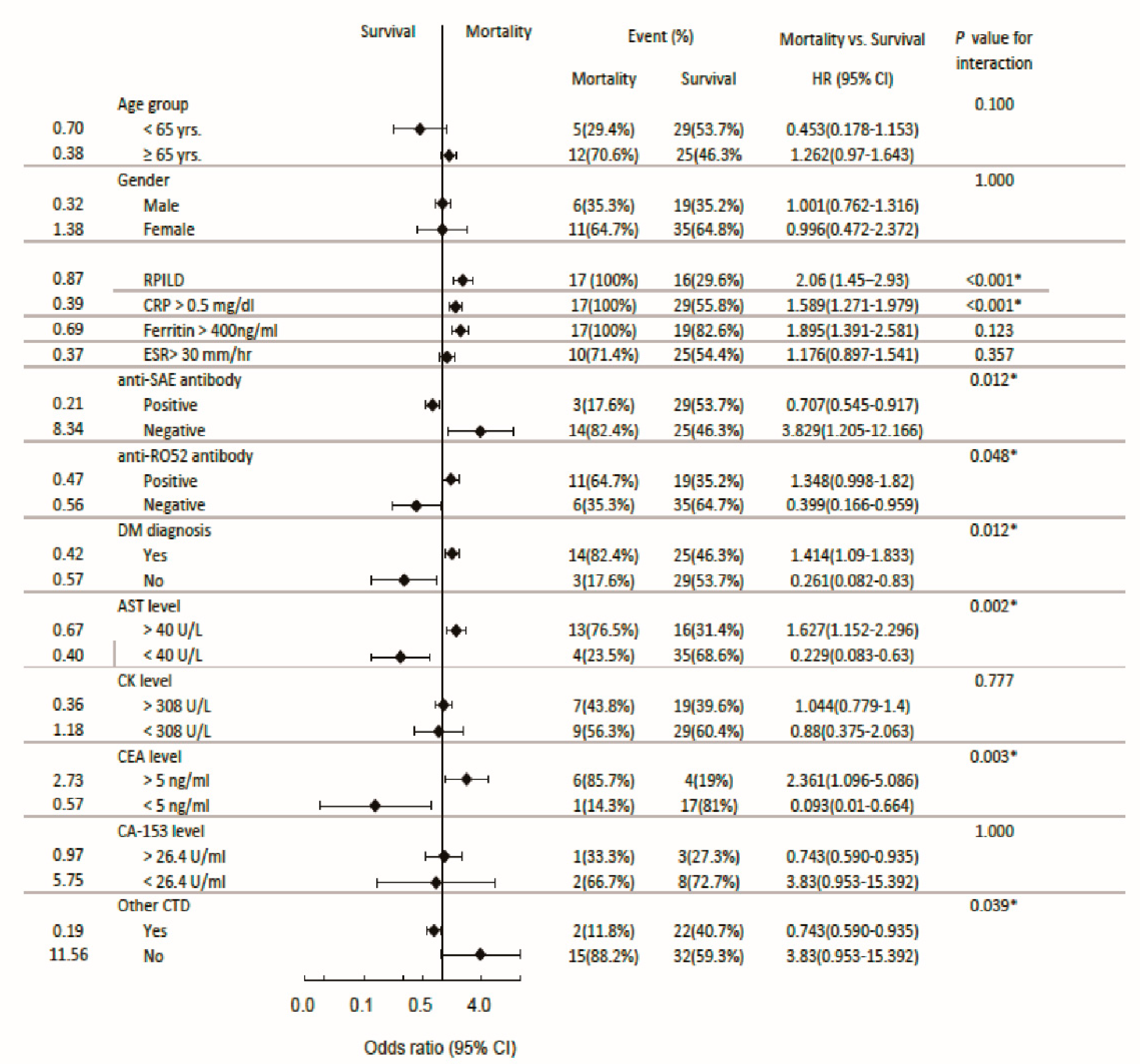

3.7. Subgroup analysis: Odds ratio for RPILD and mortality

4. Discussion

Funding

Authors’ Contributions

Declaration of conflicting interests

References

- Tang, K.; Zhang, H.; Jin, H. Clinical characteristics and management of patients with clinical amyopathic dermatomyositis: a retrospective study of 64 patients at a tertiary dermatology department. Front. Med. (Lausanne) 2021, 8, 783416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, H.; Pan, M.; Kang, Y.; Xia, Q.; Li, X.; Zhao, X.; Shi, R.; Lou, J.; Zhou, M.; Kuwana, M.; et al. Clinical manifestations of dermatomyositis and clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis patients with positive expression of anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 antibody. Arthritis Care Res. (Hoboken) 2012, 64, 1602–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Cao, M.; Plana, M.N.; Liang, J.; Cai, H.; Kuwana, M.; Sun, L. Utility of anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 antibody measurement in identifying patients with dermatomyositis and a high risk for developing rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease: a review of the literature and a meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res. (Hoboken) 2013, 65, 1316–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koga, T.; Fujikawa, K.; Horai, Y.; Okada, A.; Kawashiri, S.-Y.; Iwamoto, N.; Suzuki, T.; Nakashima, Y.; Tamai, M.; Arima, K.; et al. The diagnostic utility of anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 antibody testing for predicting the prognosis of Japanese patients with DM. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2012, 51, 1278–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, S.; Kuwana, M. Clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2010, 22, 639–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghadam-Kia, S.; Oddis, C.V.; Sato, S.; Kuwana, M.; Aggarwal, R. Antimelanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 antibody: expanding the clinical spectrum in north American patients with dermatomyositis. J. Rheumatol. 2017, 44, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, K.; Vinik, O.; Shojania, K.; Yeung, J.; Shupak, R.; Nimmo, M.; Avina-Zubieta, J.A. Clinical spectrum and therapeutics in Canadian patients with anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (MDA5)-positive dermatomyositis: a case-based review. Rheumatol. Int. 2019, 39, 1971–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, C.; Li, W.; Xie, Q.; Yin, G. Rituximab in the treatment of interstitial lung diseases related to anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 dermatomyositis: a systematic review. Front. Immunol. 2022, 12, 820163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, S.; Chen, X.-x.; Lu, X.-y; Wu, M.-f.; Deng, Y.; Huang, W.-q.; Guo, Q.; Yang, C.-d.; Gu, Y.-y.; Bao, C.-d.; et al. Adult clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis with rapid progressive interstitial lung disease: a retrospective cohort study. Clin. Rheumatol. 2007, 26, 1647–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Gao, X.; Li, Y.; Jia, X.; Zhang, X.; Xu, Y.; Gan, Y.; Li, S.; Chen, R.; He, J.; et al. Predictors and mortality of rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease in patients with idiopathic inflammatory myopathy: a series of 474 patients. Front. Med. (Lausanne) 2020, 7, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirakashi, M.; Nakashima, R.; Tsuji, H.; Tanizawa, K.; Handa, T.; Hosono, Y.; Akizuki, S.; Murakami, K.; Hashimoto, M.; Yoshifuji, H.; et al. Efficacy of plasma exchange in anti-MDA5-positive dermatomyositis with interstitial lung disease under combined immunosuppressive treatment. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2020, 59, 3284–3292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, H.; Takeuchi, O.; Sato, S.; Yoneyama, M.; Yamamoto, M.; Matsui, K.; Uematsu, S.; Jung, A.; Kawai, T.; Ishii, K.J.; et al. Differential roles of MDA5 and RIG-I helicases in the recognition of RNA viruses. Nature 2006, 441, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miner, J.J.; Diamond, M.S. MDA5 and autoimmune disease. Nat. Genet. 2014, 46, 418–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishina, N.; Sato, S.; Masui, K.; Gono, T.; Kuwana, M. Seasonal and residential clustering at disease onset of anti-MDA5-associated interstitial lung disease. R.M.D. Open. 2020, 6, e001202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghu, G.; Remy-Jardin, M.; Richeldi, L.; Thomson, C.C.; Inoue, Y.; Johkoh, T.; Kreuter, M.; Lynch, D.A.; Maher, T.M.; Martinez, F.J.; et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (an update) and progressive pulmonary fibrosis in adults: an official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline. Am. J. Respi.r Crit. Care Med. 2022, 205, e18–e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzilas, V.; Tzouvelekis, A.; Ryu, J.H.; Bouros, D. 2022 update on clinical practice guidelines for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and progressive pulmonary fibrosis. Lancet Respir. Med. 2022, 10, 729–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarricone, E.; Ghirardello, A.; Rampudda, M.; Bassi, N.; Punzi, L.; Doria, A. Anti-SAE antibodies in autoimmune myositis: identification by unlabelled protein immunoprecipitation in an Italian patient cohort. J. Immunol. Methods. 2012, 384, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.; Lu, X.; Shu, X.; Peng, Q.; Wang, G. Clinical characteristics of anti-SAE antibodies in Chinese patients with dermatomyositis in comparison with different patient cohorts. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, H.; So, J.; Lam, T.T.-O.; Wong, V.T.-L.; Ho, R.; Li, W.L.; Mok, C.C.; Lau, C.S.; Tam, L.-S. Performance of the 2017 European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology/American College of Rheumatology classification criteria in patients with idiopathic inflammatory myopathy and anti–melanoma differentiation–associated protein 5 positivity. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2022, 74, 1588–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohan, A.; Peter, J.B. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis (first of two parts). N. Engl. J. Med. 1975, 292, 344–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohan, A.; Peter, J.B. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis (second of two parts). N Engl J Med 1975, 292, 403–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, I.E.; Tjärnlund, A.; Bottai, M.; Werth, V.P.; Pilkington, C.; de Visser, M.; Alfredsson, L.; Amato, A.A.; Barohn, R.J.; Liang, M.H.; et al. 2017 European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for adult and jvenile idiopathic inflammatory myopathies and their major subgroups. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2017, 76, 1955–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, N.; Takezaki, S.; Kobayashi, I.; Iwata, N.; Mori, M.; Nagai, K.; Nakano, N.; Miyoshi, M.; Kinjo, N.; Murata, T.; et al. Clinical and laboratory features of fatal rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease associated with juvenile dermatomyositis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2015, 54, 784–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graney, B.A.; Fischer, A. Interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2019, 16, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Guo, L.; Fu, Y.; Wang, K.; Zhang, D.; Xu, W.; Chen, Z.; Ye, S. Interstitial lung disease in anti-MDA5 positive dermatomyositis. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2021, 60, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuji, H.; Nakashima, R.; Hosono, Y.; Imura, Y.; Yagita, M.; Yoshifuji, H.; Hirata, S.; Nojima, T.; Sugiyama, E.; Hatta, K.; et al. Multicenter prospective study of the efficacy and safety of combined immunosuppressive therapy with high-dose glucocorticoid, tacrolimus, and cyclophosphamide in interstitial lung diseases accompanied by anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5-positive dermatomyositis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020, 72, 488–498. [Google Scholar]

- So, H.; Wong, V.T.L.; Lao, V.W.N.; Pang, H.T.; Yip, R.M.L. Rituximab for refractory rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease related to anti-MDA5 antibody-positive amyopathic dermatomyositis. Clin. Rheumatol. 2018, 37, 1983–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurasawa, K.; Arai, S.; Namiki, Y.; Tanaka, A.; Takamura, Y.; Owada, T.; Arima, M.; Maezawa, R. Tofacitinib for refractory interstitial lung diseases in anti-melanoma differentiation-associated 5 gene antibody-positive dermatomyositis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2018, 57, 2114–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McPherson, M.; Economidou, S.; Liampas, A.; Zis, P.; Parperis, K. Management of MDA-5 antibody positive clinically amyo9athic dermatomyositis associated interstitial lung disease: a systematic review. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2022, 53, 151959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 30 You, H.; Wang, L.; Wang, J.; Lv, C.; Xu, L.; Yuan, F.; Li, J.; Wu, M.; Zhou, S.; Da, Z.; et al. Time-dependent changes in RPILD and mortality risk in anti-MDA5+ DM patients: a cohort study of 272 cases in China. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2023, 62, 1216–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Qiao, J.; Tang, S.; Pan, Y.; Li, S.; Yang, C.; Fang, H. Elevated carcinoembryonic antigen predicts rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease in clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2021, 60, 3896–3903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, Y.; Ye, L.; Chen, F.; Shen, Y.; Lu, X.; Wang, G.; Shu, X. Different multivariable risk factors for rapid progressive interstitial lung disease in anti-MDA5 positive dermatomyositis and anti-synthetase syndrome. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 845988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- So, J.; So, H.; Wong, V.T.-L.; Ho, R.; Wu, T.Y.; Wong, P.C.-H.; Tam, L.H.-P.; Ho, C.; Lam, T.T.-O.; Chung, Y.K.; et al. Predictors of rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease and mortality in patients with autoantibodies against melanoma differentiation-associated protein 5 dermatomyositis. Rheumatology (Oxford), 4444. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, L.K.; Jaskowski, T.D.; La’Ulu, S.L.; Tebo, A.E. Antibodies to small ubiquitin-like modifier activating enzyme are associated with a diagnosis of dermatomyositis: results from an unselected cohort. Immunol. Res. 2018, 66, 431–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodoki, L.; Nagy-Vincze, M.; Griger, Z.; Betteridge, Z.; Szöllősi, L.; Dankó, K. Four dermatomyositis-specific autoantibodies-anti-TIF1γ, anti-NXP2, anti-SAE and anti-MDA5-in adult and juvenile patients with idiopathic inflammatory myopathies in a Hungarian cohort. Autoimmun. Rev. 2014, 13, 1211–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muro, Y.; Sugiura, K.; Akiyama, M. Low prevalence of anti-small ubiquitin-like modifier activating enzyme antibodies in dermatomyositis patients. Autoimmunity 2013, 46, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, C.; Sun, Y.; Huang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Pan, R.; Xu, K.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Z. Myositis specific antibodies are associated with isolated anti-Ro-52 associated interstitial lung disease. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2022, 61, 1083–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavagna, L.; Meloni, F.; Meyer, A.; Sambataro, G.; Belliato, M.; de Langhe, E.; Cavazzana, I.; Pipitone, N.; Triantafyllias, K.L.; Mosca, M.; et al. Clinical spectrum time course in non-Asian patients positive for anti-MDA5 antibodies. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol.

| Total Patients (n=71) |

RPILD* (n=33) |

Non RPILD (n=38) |

Concurrent anti-SAE Abs (n=32) |

Concurrent anti-Ro52 Abs (n=30) |

Mortality (n=17) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (%) | 25 (35.2%) | 10 (30.3%) | 15(39.5%) | 14(43.8%) | 6(20%) | 6(35.3%) |

| Female (%) | 46 (64.8%) | 23 (69.7%) | 23(60.5%) | 18(56.3%) | 24(80%) | 11(64.7%) |

| Mean age (SD**) | 63.4 (13.9) | 65.5 (11.1) (p=0.239) |

61.6 (15.8) (p=0.238) |

64.5 (14.2) (p=0.546) |

60.9 (13.5) (p=0.192) |

67.1 (9.4) (p=0.21) |

| DM/PM (%) | 39 (55%) | 22 (56.4%) | 17 (43.6%) | 8 (25%) | 22 (73.3%) | 14 (82.4%) |

| AST (SD**) U/L |

79.8 (105.9) | 97.9 (126.5) | 63.6 (82.0) | 61.0 (89.5) (p=0.194) |

106.1 (132.5) (p=0.086) |

107.9 (82.8) (p=0.209) |

| LDH (SD**) U/L | 411.8 (179.7) | 427.5 (205.7) | 397.0 (152.9) | 360.8 (127.3) (p=0.043) |

448.1 (218.7) (p=0.139) |

508.3 (237.5)(p=0.009) |

| CK (SD**), U/L | 928.1 (2318.8) | 504.2 (847.4) | 1279.3 (3015.2) | 832.4 (2931.7) (P=0.926) |

959.3 (1732.9) (P=0.059) |

629.8 (1084.8)(P=0.234) |

| Myoglobulin (SD**), ng/ml | 574.5 (851.6) | 548.1 (819.1) | 606.8 (938. 9) | 157.6 (122.4) (p=0.11) |

582.4 (854.6) (p=0.968) |

448.3 (693.6) (p=0.602) |

| CRP (S.D.**) mg/dl | 4.17 (6.80) | 6.03 (8.18) | 2.46 (4.74) | 4.25 (6.18) (p=0.937) |

3.36 (6.56) (p=0.405) |

8.78 (8.97) (p=0.001) |

| ESR (S.D.**) mm/hr |

50.0 (35.9) | 56.2 (36.6) | 44.5 (34.9) | 47.5 (35.3) (p=0.634) |

50.4 (32.8) (p=0.94) |

61.3 (34.4)(p=0.18) |

| Albumin (S.D.**), g/dl | 3.32 (0.79) | 3.11 (0.82) | 3.56 (0.69) | 3.57 (0.84) (p=0.037) |

3.10 (0.74) (p=0.098) |

2.58 (0.43) (p=<0.001) |

| CA-153(S.D.**), U/ml |

19.9 (17.8) | 32.9 (18.8) | 10.1 (9.2) | 10.5 (10.5) (p=0.087) |

26.1 (7.8)(p=0.517) | 29.0 (12.8) (p=0.339) |

| CEA (S.D.**), ng/ml | 7.8 (7.4) | 12.5 (8.4) | 4.2 (3.9) | 6.9 (6.7) (p=0.569) |

11.0 (9.8) (p=0.239) |

15.2 (8.6) (p=0.001) |

| IgE (S.D.**), KU/L |

260.7 (306.8) | 310.9 (378.1) | 188.1 (150.3) | 298.1 (402.8) (p=0.58) |

155.1 (215.9) (p=0.335) |

392.0 (491.9) (p=0.176) |

| Ferritin (S.D.**) ng/ml | 1722.2 (1920.2) | 2449.8 (2152.8) | 630.8 (602.0) | 1063.3 (1338.1) (p=0.076) |

2245.4 (1982.7) (p=0.120) |

3178.2 (2147.4)(p<0.001) |

| Smoking (%) | 16 (22.5%) | 5 (15.2%) | 11 (28.9%) | 9 (56.3%) | 4 (25%) | 2 (11.8%) |

| Malignancy (%) | 15 (21.1%) | 11 (73.3%) | 4 (26.7%) | 5 (33.3%) | 2 (13.3%) | 6 (35.3%) |

| Other CTD*** (%) | 27 (38%) | 10 (41.7%) | 14 (58.3%) | 13 (54.2%) | 13 (54.2%) | 2 (11.8%) |

| Anti-SAE antibody (%) | 32 (45.1%) | 9 (28.1%) | 23 (71.9%) | 5 (15.6%) | 3 (17.6%) | |

| Anti-Ro52 antibody (%) | 30 (42.3%) | 19 (63.3%) | 11 (36.7%) | 5 (15.6%) | 11 (64.7%) | |

| Mortality (%) | 17 (23.9%) | 17 (100%) | 0 (0) | 3 (17.6%) | 11 (64.7%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).