1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Children’s mental health is a fundamental component of their overall well-being, with far-reaching implications for their development. Therefore, the prevalence of mental health problems such as depression and anxiety in children is a global health concern [

1,

2]. Recent meta-analysis showed that the prevalence of depression and anxiety symptoms were 25.2% and 20.5% among children and adolescents globally [

1]. Therefore, understanding the multifaceted factors contributing to these conditions is important for effective intervention and policy development.

More specifically, the prevalence and determinants of mental health outcomes among Iraqi children is crucial to be explored due to the enduring impact of conflict, displacement, and societal instability in this middle eastern country. The conflict and instability have exposed Iraqi children and their families to a range of traumatic experiences, including violence, displacement, and loss, which can significantly contribute to a high prevalence of mental health problems [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. Additionally, limited access to quality healthcare and psychosocial support further exacerbates the situation [

8]. Social and cultural factors, such as stigma surrounding mental health, can also hinder access to care and contribute to the persistence of mental health problems [

9,

10]. Addressing the mental health needs of children in Iraq requires a comprehensive understanding of the determinants in order to design multifaceted approach that encompasses not only clinical interventions but also efforts to promote stability, security, and community support.

Children’s mental health may be impacted by exposure to neighborhood violence and the resulting feeling of loss of safety. Anxiety, depression, and PTSD are just a few of the negative mental health outcomes that can result from exposure to violence and instability [

11]. As a result of the perceived threat, children growing up in such settings frequently experience an increased state of alertness, which may have long-term effects on their emotional wellbeing [

12]. As children try to deal with the unpredictability and danger that surround them, living in an unsafe community might lead to the development of anxiety disorders and depressive symptoms.

On the other hand, witnessing or experiencing domestic violence can have profound and lasting effects on a child’s mental health. Children grow up surrounded by domestic violence between caregivers often internalize feelings of helplessness, guilt, and fear. Witnessing such violence can distort their understanding of healthy relationships and coping mechanisms, leading to an increased likelihood of developing anxiety and depression. [

13]. Adding to that, acceptance of domestic violence may normalize this harmful behavior, creating an environment where children are more likely to witness such violence and endure its psychological consequences [

14]. This acceptance further perpetuates the cycle of violence, making it crucial to examine the societal level factors within a social ecological model to fully understand their role in children’s mental well-being.

Finally, severe corporal punishment, characterized by harsh physical discipline, can also contribute to the development of negative mental health outcomes in children [

15,

16]. Children subjected to such punitive measures often experience feelings of shame, humiliation, and fear [

16]. Instead of learning constructive ways to manage their behaviors, they may internalize a belief that violence is an acceptable solution to problems. This distorted perspective can lead to heightened levels of stress, anxiety, and low self-esteem as children grapple with the emotional fallout of punitive discipline [

15,

16]. However, the acceptability and prevalence of corporal punishment vary across cultures and regions. Some studies may reflect the specific cultural norms and contexts in which they were conducted, making it challenging to generalize findings to diverse populations with different cultural perspectives on discipline [

17,

18].

In light of these complexities and variations in research findings, it is crucial to approach the topic of corporal punishment and children’s mental health with a balanced perspective. While numerous studies suggest a link between severe corporal punishment and negative mental health outcomes, it is also essential to acknowledge that not all research findings are uniform, and further investigation is needed to fully understand the details of this relationship.

Therefore, it is important to recognize that these factors often do not exist in isolation; children may experience a combination of community violence, domestic violence, and severe corporal punishment. The impact of these experiences can magnify their effects on mental health. Early intervention is crucial in breaking the cycle of adversity and mental health struggles. As such, the objectives of this study were 1) to conduct a nationwide analysis to explore how violence at multiple socio-ecological levels and children depression and anxiety, 2) to identify the most vulnerable children according to the spatial distribution of Iraqi governorates.

1.2. Theoretical framework

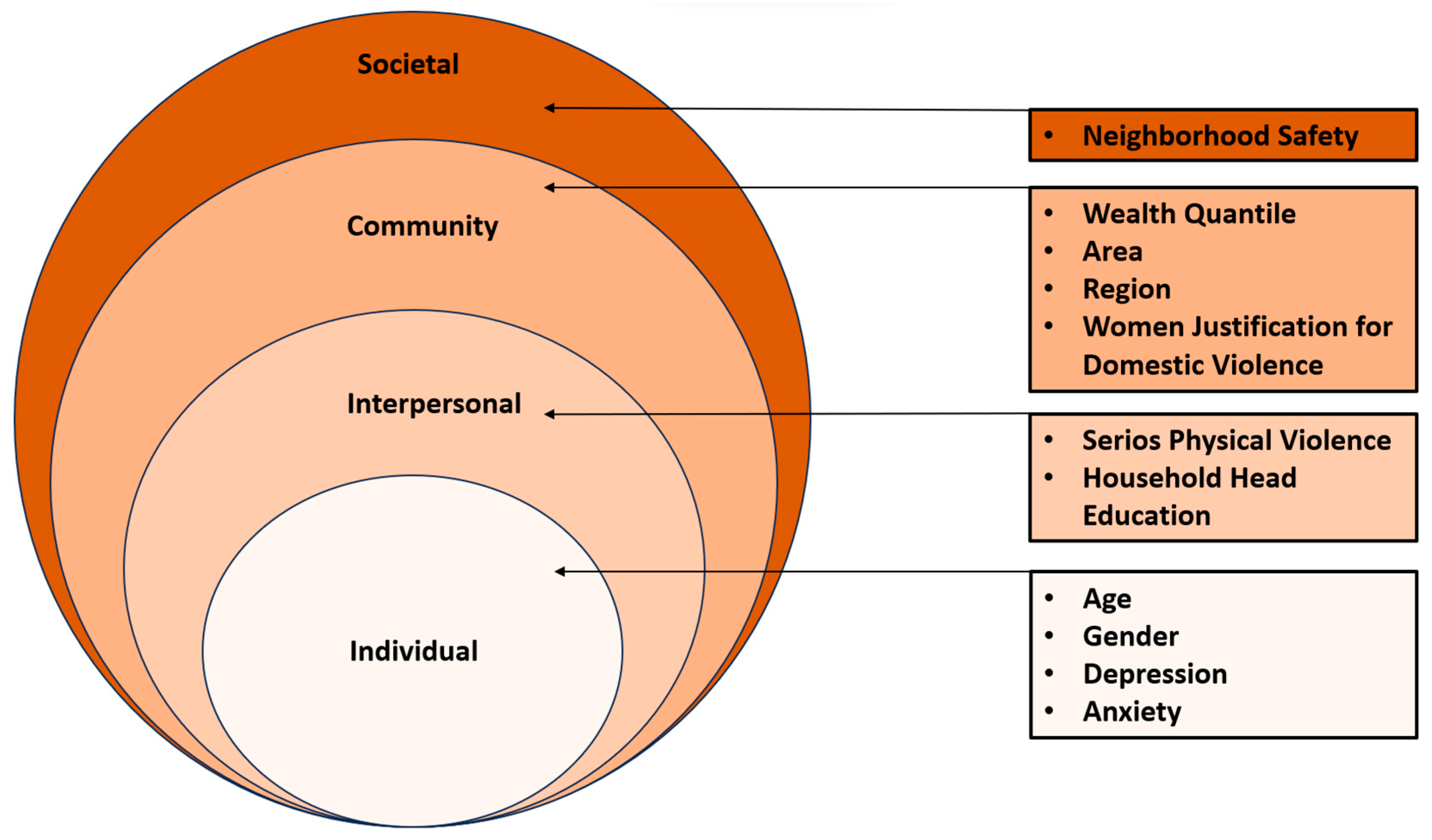

The Social Ecological Model (SEM), initially proposed by Bronfenbrenner and Morris in 1998, serves as a powerful theoretical lens through which to examine how individual and environmental factors intersect to shape health outcomes [

19]. This model outlines relations across four distinct levels: the individual, interpersonal, community, and societal levels. Within the context of children’s mental health, SEM emphasizes that adverse outcomes cannot be attributed to a single isolated factor but rather emerge from the complex relationship of factors operating at these multiple ecological levels [

19].

In accordance with the SEM framework, this study delves into the role of violence across various ecological levels as a determinant of adverse mental health outcomes among Iraqi children. This study builds upon prior research and applies SEM to investigate how individual, interpersonal, community, and societal factors collectively contribute to depression and anxiety among this vulnerable population [

20,

21].

Figure 1.

Study variables predicting children’s anxiety and depression according to the social ecological framework.

Figure 1.

Study variables predicting children’s anxiety and depression according to the social ecological framework.

2. Materials and Methods

The objectives of this study were 1) to conduct a nationwide analysis to explore the factors associated with depression and anxiety among Iraqi children according to social ecological framework, 2) to identify the most vulnerable children according to the spatial distribution of Iraqi governorates.

2.1. The Survey

The Iraq Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) was used in this study. MICS, an international multipurpose household survey created in the 1990s, aims to assist nations in gathering internationally comparable data on a wide range of variables pertaining to the situation of women and children. MICS measures important indicators that enable nations to produce statistics for use in national development goals, programs, and policies. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and other international commitments are being tracked using MICS more lately.

With cooperation from UNICEF, the Iraqi government released the findings of the Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS 6) before the end of 2018. The country’s progress toward the SDG targets must be driven by these survey criteria. The sample method for the Iraq MICS 2018 was created to produce estimates for a wide range of indicators covering the well-being of women and children at many levels, including national, regional, and governorate-specific levels, embracing both urban and rural sectors. 20520 sampled households were included in the survey from a total of 1710 sampled Enumeration Areas (EAs), with 12 households being randomly chosen within each EA. Estimates are prepared for the 18 governorates namely, Dohuk, Nainawa, Sulaimaniya, Kirkuk, Erbil, Diala, Anbar, Baghdad, Bab il, Karbalah, Wasit, Salahaddin, Najaf, Qadisyah, Muthana, Thiqar, Musan, and Basrah [

22].

12,382 caregivers were specifically included in our study, and they provided detailed information about their parenting and disciplinary methods for kids between the ages of 5 and 14. Children between the ages of 15 and 17 were not covered by the data gathering tool. It’s significant to highlight that just one child per family was randomly selected for this poll. As a result, no statistical modifications were required to take into account potential data clustering within families or households, where children from the same family might show more statistical similarity than children from other families. UNICEF (2019) Iraq Multiple Cluster Survey 2018: Survey Findings Report. contains comprehensive information about the sample and sampling methodology.

2.2. Study Variables

In this study, the outcome variables were two binary variables that were coded to measure negative mental outcomes among Iraqi children, based on the caregiver perception. Our first measure, Depressive symptoms, is based on whether the caregiver reported that, over the past month, the child seemed very sad or depressed at least once a week (Yes vs No). Anxiety is based on whether the caregiver reported that, over the past month, the child seemed very anxious, nervous, or worried at least once a week (Yes vs No). This methodology is consistent with the approach used by Logan et al [

21].

The rest of the study variables were selected to align with the four levels of the SEM. Individual level factors were child age (5-9, 10-14) and Child sex (male, female). Interpersonal level variables included parental discipline using serious physical violence, is measured using a series of categorical dummy variables based on a hierarchy of severity logic whereby more than one disciplinary method is reported by caregivers. Serious physical discipline includes caregivers who reported disciplining their child by shaking the child, hitting the child with an object (e.g., a belt), hitting the child in the face, the head or the ear, and/or beating the child as hard as possible coded as (Yes vs No).Also, interpersonal level variables included household head education (Pre-primary or none, Primary, Lower secondary, Upper secondary and beyond).

Community level variables were area (urban, rural), region (Kurdistan, South/Central Iraq), wealth index (poorest, poorest, middle, richer, richest), and domestic violence acceptance among women. This was a binary variable with two responses (yes) indicating acceptance and (no) indicating opposition. Domestic violence acceptance among women was assessed using a set of fixed response yes/no questions related to different circumstances in which a husband might be perceived justified in hitting or beating his wife. These circumstances included (1) the wife going out without informing the husband, (2) neglecting the children, (3) engaging in arguments with the husband, (4) refusing to have sex with the husband, (5) burning the food, (6) the husband feeling that she is wasteful, and (7) exposing household secrets. Domestic violence acceptance among women was categorized as (yes) if at least one of the seven situations was endorsed with an affirmative answer and as (no) if none of the situations were endorsed. This categorization was introduced by other researchers [

23,

24].

The societal-level variable that was included in this study pertained to the perceived safety within one’s neighborhood, specifically focusing on the sense of security while walking alone in the neighborhood after nightfall. Respondents had a range of response options, including (1) feeling “very safe,” (2) “safe,” (3) “unsafe,” (4) “very unsafe,” and (7) “never do this.” In line with prior research, both safety variables’ responses were transformed into a binary format, as per the method established by Emerson and Llewellyn in 2023 [

25]. “Very safe” and “safe” were consolidated as “safe,” while “unsafe,” “very unsafe,” and “never do this” were combined as “unsafe.”

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The first step of the analysis was done by conducting a descriptive analysis to estimate the prevalence of depression and anxiety among children along with the rest of the study variables. Subsequently, multivariate logistic regression models predicting children’s anxiety and depression were built adjusting for the study variables according to the four levels of SEM. (See

Table 1 and

Table 2). The data compilations and analyses were conducted using IBM® SPSS® Statistics version 27. The significance level was set at (

P<0.05). The adjusted odds ratios (aOR) and the 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were reported for each independent variable. (See

Table 2)

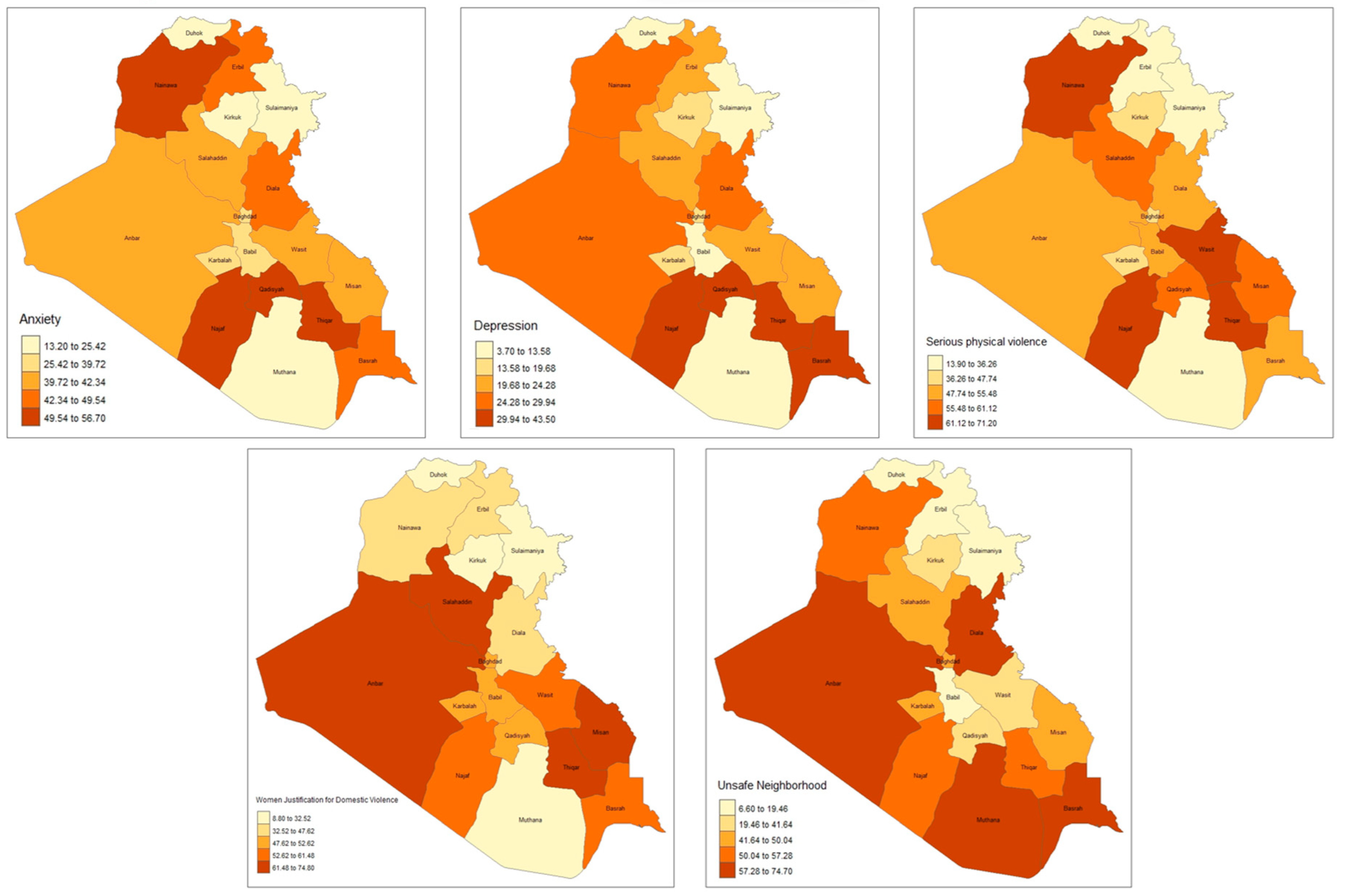

To investigate the spatial distribution of the important study variables R software was used to create maps showing the 18 Iraqi governorates. The mapped variables include children anxiety, children depression, children discipline practices using serious physical violence, domestic violence acceptance, and neighborhood safety. (See Figure 2)

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

Table 1 provides an overview of the study sample’s key characteristics. Notably, 22% of the children had symptoms of depression, while 38% showed signs of anxiety. Children 5-9 years old were 57%. The use of severe physical violence to discipline children by caregivers was reported in 48% of cases, while 44% of women justified domestic violence. Additionally, 40% of household heads had either no education, pre-primary education, or primary education. The majority of caregivers resided in urban areas, making up 61% of the total sample. When it came to neighborhood safety, 41% of caregivers expressed feeling unsafe walking in their neighborhood after dark. For a more comprehensive breakdown of sociodemographic characteristics, please refer to

Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics (N = 12,382).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics (N = 12,382).

| |

Characteristics |

N |

% |

| Individual |

Depression |

No |

9670 |

78.2 |

| |

|

Yes |

2688 |

21.8 |

| |

Anxiety |

No |

7655 |

61.9 |

| |

|

Yes |

4706 |

38.1 |

| |

Child Age |

5-9 |

7009 |

56.7 |

| |

|

10-14 |

5352 |

43.3 |

| |

Child Sex |

Male |

6391 |

51.7 |

| |

|

Female |

5970 |

48.3 |

| Interpersonal |

Serios Physical Violence |

No |

6474 |

52.5 |

| |

|

Yes |

5857 |

47.5 |

| |

Household Head Education |

Pre-primary or none |

1223 |

9.9 |

| |

|

Primary |

3830 |

31.0 |

| |

|

Lower secondary |

2509 |

20.3 |

| |

|

Upper secondary and beyond |

2968 |

24.0 |

| Community |

Women Justification for Domestic Violence |

No |

5751 |

46.5 |

| |

|

Yes |

5438 |

44.0 |

| |

Wealth Quintile |

Poorest |

2870 |

23.2 |

| |

|

Second |

2449 |

19.8 |

| |

|

Middle |

2182 |

17.7 |

| |

|

Fourth |

1999 |

16.2 |

| |

|

Richest |

1784 |

14.4 |

| |

Area |

Urban |

7534 |

60.9 |

| |

|

Rural |

3776 |

33.4 |

| |

Region |

Kurdistan |

1429 |

11.6 |

| |

|

South Central |

9881 |

79.9 |

| Societal |

Unsafe Neighborhood |

No |

6277 |

50.8 |

| |

|

Yes |

5007 |

40.5 |

Figure 2 illustrates the spatial distribution of key study variables across Iraq’s 18 governorates. The prevalence of child anxiety was notably higher than the national prevelance, ranging from 50% to 57%, in Najaf, Thiqar, Qadisyah, and Nainawa. Similarly, child depression exhibited higher prevelence, ranging from 30% to 44%, in Najaf, Thiqar, Qadisyah, and Basrah.

Governorates with the most significant prevalence of reported severe physical violence (61% to 71%) were Najaf, Thiqar, Wasit, and Nainawa. On the other hand, the acceptance of domestic violence was more prevalent in the South/Central region of Iraq, particularly in Anbar, Salahaddin, Thiqar, and Misan governorates, but notably lower in the Kurdistan region, specifically Dohuk, Sulaimaniya, and Erbil governorates. This pattern was also observed in the distribution of unsafe neighborhoods (refer to Figure 2 for further details).

Figure 1.

Spatial distribution of study variables according to 18 Iraqi governorates.

Figure 1.

Spatial distribution of study variables according to 18 Iraqi governorates.

3.2. Logistic Regression Analyses

Table 2 presents the results of two logistic regression analysis models, one for predicting children’s depression and the other for predicting children’s anxiety. These models assessed the associations between study variables according to the SEM.

In the model predicting children’s depression, individual-level variables (age and serious physical violence) were found to be associated with children’s depression. Moreover, at the interpersonal level, women’s justification for domestic violence (AOR = 1.27, 95% CI: 1.15, 1.41) demonstrated a significant association with children’s depression. Several community-level factors also showed associations with children’s depression, including the wealth index, region (AOR = 1.91, 95% CI: 1.51, 2.38), and area (AOR = 0.74, 95% CI: 0.66, 0.83). Additionally, the societal-level indicator, “neighborhood safety,” was found to be significantly associated with children’s depression (AOR = 1.18, 95% CI: 1.07, 1.30). For a detailed breakdown of these results, please refer to

Table 2.

In the model predicting children’s anxiety, individual-level variables (gender and serious physical violence) demonstrated associations with children’s anxiety. Furthermore, at the interpersonal level, women’s justification for domestic violence (AOR = 1.54, 95% CI: 1.06, 1.26) exhibited a significant association with children’s anxiety. Several community-level factors also showed significant association with children’s anxiety, including the wealth index, region (AOR = 1.55, 95% CI: 1.31, 1.83), and area (AOR = 0.79, 95% CI: 0.72, 0.87). Notably, the societal-level indicator, “neighborhood safety,” displayed a significant association with children’s anxiety (AOR = 1.09, 95% CI: 1.00, 1.19). For a detailed breakdown of these findings, please refer to

Table 2.

Table 2.

Multi variate logistic regression analysis modeling depression and anxiety among Iraqi Children (n=12,382).

Table 2.

Multi variate logistic regression analysis modeling depression and anxiety among Iraqi Children (n=12,382).

| |

Characteristics |

|

Depression |

|

Anxiety |

|

| |

|

|

OR

95% CI |

P value |

OR

95% CI |

P value |

| Individual |

Child Age, Ref= (5-9) years |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

10-14 |

1.15 (1.06-1.26) |

<0.001 |

0.94 (0.88-1.01) |

0.65 |

| |

Child Sex, Ref=Female |

Male |

0.92 (0.8-1.01) |

0.54 |

0.73 (0.67-0.79) |

<0.001 |

| Interpersonal |

Serios Physical Violence, Ref=No |

Yes |

1.51 (1.37-1.67) |

<0.001 |

1.85 (1.70-2.01) |

<0.001 |

| |

Household Head Education, Ref= Pre-primary or none |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Primary |

1.13 (0.95-1.34) |

0.308 |

1.04 (0.90-1.21) |

0.81 |

| |

|

Lower secondary |

1.12 (0.93-1.34) |

0.446 |

1.12 (0.95-1.31) |

0.32 |

| |

|

Upper secondary and beyond |

1.19 (0.98-1.43) |

0.174 |

1.15 (0.98-1.34) |

0.18 |

| Community |

Women Justification for Domestic Violence, ref=No |

Yes |

1.28 (1.16-1.42) |

<0.001 |

1.16 (1.06-1.26) |

0.001 |

| |

Wealth Quintile, Ref= Poorest |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Second |

0.89 (0.77-1.02) |

0.109 |

1.01 (0.89-1.14) |

0.87 |

| |

|

Middle |

0.79 (0.68-0.92) |

0.002 |

0.97 (0.85-1.11) |

0.65 |

| |

|

Fourth |

0.75 (0.64-0.89) |

0.001 |

0.89 (0.77-1.02) |

0.10 |

| |

|

Richest |

0.59 (0.47-0.73) |

<0.001 |

0.72 (0.60-0.86) |

<0.001 |

| |

Region, Ref= Kurdistan |

South Central |

1.87 (1.49-2.34) |

<0.001 |

1.53 (1.30-1.81) |

<0.001 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Area, Ref=Rural |

Urban |

1.35 (1.49-2.34) |

<0.001 |

0.80 (0.72-0.88) |

<0.001 |

| Societal |

Unsafe Neighborhood, Ref=No |

Yes |

1.18 (1.07-1.30) |

0.001 |

1.09 (1.00-1.19) |

0.04 |

4. Discussion

The objectives of this study were 1) to conduct a nationwide analysis to explore how violence at multiple socio-ecological levels is associated with children depression and anxiety, 2) to identify the most vulnerable children according to the spatial distribution of Iraqi governorates. The study revealed that nationwide, the prevalence of children with depression and anxiety were 22% and 38% respectively. Yet, children living in South/Central regions of Iraq showed higher prevalence of depression and anxiety namely Najaf, Thiqar, Qadisyah where the prevalence was (30%-44%) and (50%-57%), respectively. Similar spatial patterns emerged when exploring the prevalence of violence exposure across various levels. Furthermore, the presence of violence exposure across multiple levels was significantly associated with a higher likelihood of children experiencing depression and anxiety.

Significant associations were found by the regression analyses. Particularly, exposure to interpersonal level violence, such as using severe physical violence to raise a child, is associated with a child’s development of anxiety and depression. According to research, children who experience such harsh and aggressive disciplinary measures have a greatly increased probability of developing anxiety and depressive illnesses [

26,

27]. The fear, stress, and powerlessness that come with experiencing severe physical abuse can impair a child’s sense of safety and security, making it more difficult for them to build healthy relationships and deal with the difficulties of life [

28]. It is crucial to highlight that Iraq currently lacks comprehensive legal safeguards to protect children from exposure to violence. Inconsistent with the principles of Sustainable Development Goal 16.2, which seeks to end all forms of violence against children, existing Iraqi legislation permits parents to discipline their children using physical punishment, as described in Article 41(1) of the Iraqi Penal Code [

29,

30,

31,

32]. As part of our commitment to the SDGs, it is essential to revisit and amend these legal provisions, ensuring the protection and well-being of our children.

At the community level, violence exposure like justification of domestic violence by women showed a significant association with a child’s depression and anxiety. When women tolerate or justify domestic violence, it can create a hostile and unsafe environment for children [

33]. Witnessing such attitudes can have a profound impact on a child’s emotional well-being. It can lead to feelings of insecurity, fear, and trauma, which can manifest as symptoms of depression and anxiety [

13,

34]. Moreover, communities that approve domestic violence may normalize harmful behaviors, making it more challenging for children to seek help or support. Therefore, addressing and challenging these harmful norms and attitudes is crucial to promoting the mental health and well-being of Iraqi children and breaking the cycle of violence.

Significant associations between other community-level variables and children’s depression and anxiety were found. For example, living in South or Central Iraq and coming from low-income families have all been linked to an increased likelihood of developing childhood anxiety and depression. These elements foster a situation in which there may be limited access to mental health treatments and educational opportunities. Living in a community with poor infrastructure and economic possibilities can also make it difficult to access support networks for mental health, which can increase social isolation and the likelihood that children will experience sadness and anxiety [

35,

36]. It is critical to address these local inequalities if we are to improve the outcomes for Iraqi children’s mental health in these situations.

At the societal level, living in “unsafe neighborhood” was associated with significantly higher likelihood of depression and anxiety among children. Living in an environment characterized by violence and a lack of safety measures can have profound effects on a child’s mental health. Children in these neighborhoods often face chronic stressors, such as fear for their physical safety and limited outdoor play opportunities. These stressors can contribute to the development of symptoms associated with depression and anxiety [

37]. Studies showed that community violence had direct adverse consequences for youth depression [

38,

39]. Recognizing that Iraq has suffered decades of political and social disorder, which has the potential to significantly impact the mental well-being of its children, it is imperative to integrate mental health awareness programs into the school curriculum [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. These programs aim to assist Iraqi children in addressing and coping with their mental health needs, fostering the growth of a resilient and healthy generation that will shape the future of Iraq.

It’s important to interpret the results of the study with certain limitations in mind. First off, due to its cross-sectional design, this study is unable to determine causal pathways of development of depression and anxiety. When dealing with sensitive topics like violence exposure and mental health outcomes, the dependence on self-reported data collecting poses possible biases. Future studies are needed to investigate this association using longitudinal data. Also, the binary coding employed to classify violence and mental health outcomes ignores the frequency of incidences. To provide a more thorough assessment, future research should consider using continuum- and count-based metrics in addition to binary measurements.

5. Conclusions

This study provides policymakers with valuable insights to comprehensively assess indicators of children’s development of depression and anxiety. It also addresses the scarcity of information on children mental health outcomes in Iraq on national and governorate levels, emphasizing the need for urgent national-level policy discussions to achieve key Sustainable Development Goals related to ending all forms of violence against children by 2030.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.AJ.; Methodology, R.AJ.; Software, R.AJ.; Validation, R.AJ.; For mal Analysis, R.AJ.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, R.AJ.; Writing—Review and Editing, R.AJ.; Visualization, R.AJ. The author has read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

I thank the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) for providing the access to Iraq Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) data.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Racine, N.; McArthur, B.A.; Cooke, J.E.; Eirich, R.; Zhu, J.; Madigan, S. Global Prevalence of Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms in Children and Adolescents During COVID-19: A Meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr 2021, 175, 1142–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization, W. Mental health of adolescents. 2021. [cited 2023]. Availabe online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health.

- Emberti Gialloreti, L.; Basa, F.B.; Moramarco, S.; Salih, A.O.; Alsilefanee, H.H.; Qadir, S.A.; Bezenchek, A.; Incardona, F.; Di Giovanni, D.; Khorany, R.; et al. Supporting Iraqi Kurdistan Health Authorities in Post-conflict Recovery: The Development of a Health Monitoring System. Front Public Health 2020, 8, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization, W. Social Determinants of Health in Countries in Conflict: A Perspective From the Eastern Mediterranean. 2008. Availabe online: https://applications.emro.who.int/dsaf/dsa955.pdf.

- Murthy, R.S.; Lakshminarayana, R. Mental health consequences of war: a brief review of research findings. World Psychiatry 2006, 5, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Green, P.; Ward, T. The Transformation of Violence in Iraq. British Journal of Criminology 2009, 49, 609–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, J.; Hagan, J. Crimes of Terror, Counterterrorism, and the Unanticipated Consequences of a Militarized Incapacitation Strategy in Iraq. Social Forces 2018, 97, 309–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Children’s Fund, U. 2022 UNICEF Iraq’s Humanitarian Appeals. 2022. [cited 2023]. Availabe online: https://www.unicef.org/iraq/2022-unicef-iraqs-humanitarian-appeals.

- Corrigan, P.W.; Watson, A.C. Understanding the impact of stigma on people with mental illness. World Psychiatry 2002, 1, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sadik, S.; Bradley, M.; Al-Hasoon, S.; Jenkins, R. Public perception of mental health in Iraq. Int J Ment Health Syst 2010, 4, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, C.A.; Scott, R.D.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Harris, N.B.; Danese, A.; Samara, M. Adversity in childhood is linked to mental and physical health throughout life. Bmj 2020, 371, m3048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations, U. Hidden scars: How violence harms the mental health of children. 2020. [cited 2023]. Availabe online: https://violenceagainstchildren.un.org/sites/violenceagainstchildren.un.org/files/documents/publications/final_hidden_scars_lhow_violence_harms_the_mental_health_of_children.pdf.

- Moylan, C.A.; Herrenkohl, T.I.; Sousa, C.; Tajima, E.A.; Herrenkohl, R.C.; Russo, M.J. The Effects of Child Abuse and Exposure to Domestic Violence on Adolescent Internalizing and Externalizing Behavior Problems. J Fam Violence 2010, 25, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffitt, T.E. Childhood exposure to violence and lifelong health: clinical intervention science and stress-biology research join forces. Dev Psychopathol 2013, 25, 1619–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiggers, M.; Paas, F. Harsh Physical Discipline and Externalizing Behaviors in Children: A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization, W. Corporal punishment and health. 2021. [cited 2023]. Availabe online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/corporal-punishment-and-health.

- Lansford, J.E.; Dodge, K.A. Cultural Norms for Adult Corporal Punishment of Children and Societal Rates of Endorsement and Use of Violence. Parent Sci Pract 2008, 8, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naudin, C.; Gatti, V.; Kounou, K.B.; Bagnéken, C.-O.; Ntjam, M.-C.; Clément, M.-È.; Brodard, F. Physically Violent Parental Practices: A Cross-Cultural Study in Cameroon, Switzerland, and Togo. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronfenbrenner, U.; Morris, P.A. The ecology of developmental processes. 1998.

- Billings, A.G.; Moos, R.H. Comparisons of children of depressed and nondepressed parents: A social-environmental perspective. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 1983, 11, 463–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mian, N.D.; Wainwright, L.; Briggs-Gowan, M.J.; Carter, A.S. An Ecological Risk Model for Early Childhood Anxiety: The Importance of Early Child Symptoms and Temperament. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 2011, 39, 501–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Children’s Fund, U. Iraq: Monitoring the situation of children and women: Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2018; 2019.

- Lansford, J.E.; Deater-Deckard, K.; Bornstein, M.H.; Putnick, D.L.; Bradley, R.H. Attitudes justifying domestic violence predict endorsement of corporal punishment and physical and psychological aggression towards children: a study in 25 low- and middle-income countries. J Pediatr 2014, 164, 1208–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhowmik, J.; Biswas, R.K. Married Women’s Attitude toward Intimate Partner Violence Is Influenced by Exposure to Media: A Population-Based Spatial Study in Bangladesh. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 3447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, E.; Llewellyn, G. Exposure of Women With and Without Disabilities to Violence and Discrimination: Evidence from Cross-sectional National Surveys in 29 Middle- and Low-Income Countries. J Interpers Violence 2023, 38, 7215–7241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Bellis, M.D.; Zisk, A. The biological effects of childhood trauma. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 2014, 23, 185–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morelli, N.M.; Hong, K.; Garcia, J.; Elzie, X.; Alvarez, A.; Villodas, M.T. Everyday Conflict in Families at Risk for Violence Exposure: Examining Unique, Bidirectional Associations with Children’s Anxious- and Withdrawn-Depressed Symptoms. Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology 2023, 51, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Odhayani, A.; Watson, W.J.; Watson, L. Behavioural consequences of child abuse. Can Fam Physician 2013, 59, 831–836. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- International Labour Organization, I. Database of national labour, social security and related human rights legislation: raq (232) > Criminal and penal law (5). 2012. Availabe online: https://www.ilo.org/dyn/natlex/natlex4.detail?p_lang=en&p_isn=57206&p_country=IRQ&p_count=232&p_classification=01.04&p_classcount=5.

- Equity Now, E. Discriminatory Laws: Iraq – Penal Code No. 111 Of 1969. 2021; Availabe online: https://www.equalitynow.org/discriminatory_law/iraq_-_penal_code_no_111_of_1969/#:~:text=The%20Law%3A-,Article%2041%20of%20the%20Iraqi%20Penal%20Code%20No.,while%20exercising%20a%20legal%20right.

- End Corporal Punishment, E. Country Report for Iraq. 2022. [cited 2023]. Availabe online: https://endcorporalpunishment.org/reports-on-every-state-and-territory/iraq/.

- United Nations, U. Violence against children. 2020. [cited 2023]. Availabe online: https://sdgs.un.org/topics/violence-against-children.

- Lloyd, M. Domestic Violence and Education: Examining the Impact of Domestic Violence on Young Children, Children, and Young People and the Potential Role of Schools. Front Psychol 2018, 9, 2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wathen, C.N.; Macmillan, H.L. Children’s exposure to intimate partner violence: Impacts and interventions. Paediatr Child Health 2013, 18, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Knifton, L.; Inglis, G. Poverty and mental health: policy, practice and research implications. BJPsych Bull 2020, 44, 193–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandt, L.; Liu, S.; Heim, C.; Heinz, A. The effects of social isolation stress and discrimination on mental health. Transl Psychiatry 2022, 12, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coley, R.L.; Lynch, A.D.; Kull, M. Early Exposure to Environmental Chaos and Children’s Physical and Mental Health. Early Child Res Q 2015, 32, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foell, A.; Pitzer, K.A.; Nebbitt, V.; Lombe, M.; Yu, M.; Villodas, M.L.; Newransky, C. Exposure to community violence and depressive symptoms: Examining community, family, and peer effects among public housing youth. Health Place 2021, 69, 102579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preuß, M.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.; Marquez, S.; Cirach, M.; Dadvand, P.; Triguero-Mas, M.; Gidlow, C.; Grazuleviciene, R.; Kruize, H.; Zijlema, W. Low Childhood Nature Exposure is Associated with Worse Mental Health in Adulthood. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).