Submitted:

18 December 2023

Posted:

20 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and methods

Mosquito sampling

DNA extraction and Wolbachia detection

Strain characterization and MLST genotyping

Temperature data collection and statistical analysis

Results

Wolbachia prevalence

Wolbachia strain characterization

MLST genotyping

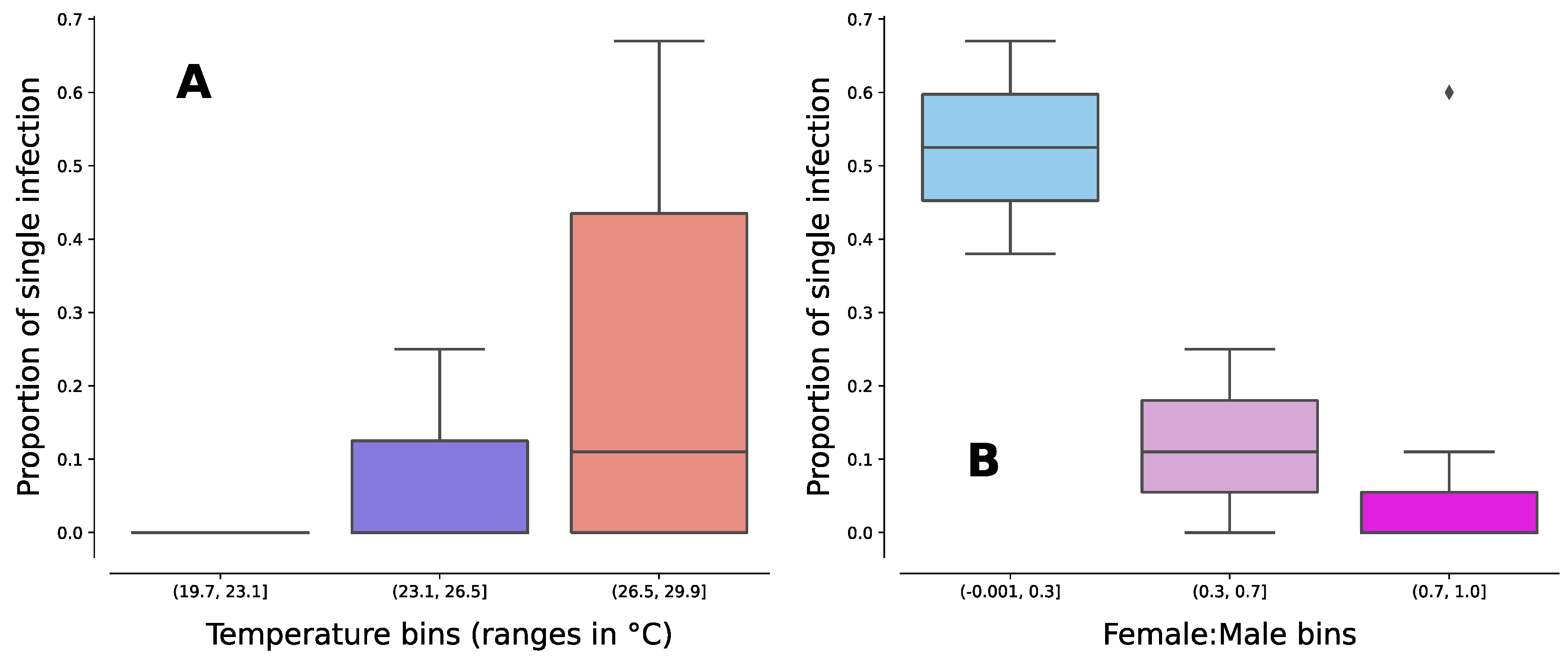

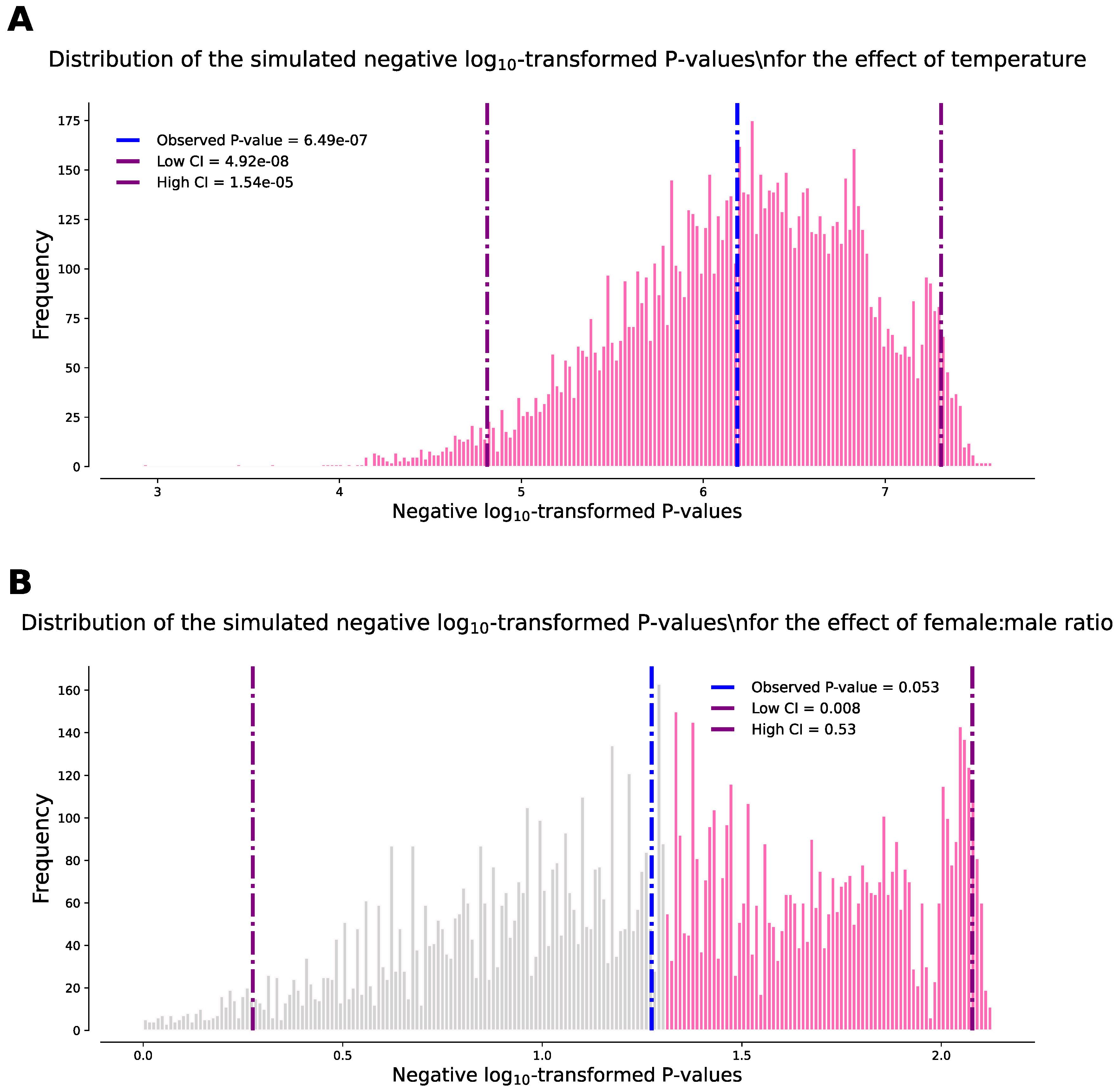

Temperature and sex ratio effect on single Wolbachia infection

Discussion

Acknowledgments

References

- Swan, T.; Russell, T.L.; Staunton, K.M.; Field, M.A.; Ritchie, S.A.; Burkot, T.R. A Literature Review of Dispersal Pathways of Aedes Albopictus across Different Spatial Scales: Implications for Vector Surveillance. Parasit. Vectors 2022, 15, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samanidou-Voyadjoglou, A.; Patsoula, E.; Spanakos, G.; Vakalis, N.C. Confirmation of Aedes Albopictus (Skuse) (Diptera: Culicidae) in Greece. Eur. Mosq. Bull. 2005, 19, 10–11. [Google Scholar]

- Badieritakis, Ε.; Papachristos, D.; Latinopoulos, D.; Stefopoulou, A.; Kolimenakis, A.; Bithas, K.; Patsoula, Ε.; Beleri, S.; Maselou, D.; Balatsos, G.; et al. Aedes Albopictus (Skuse, 1895) (Diptera: Culicidae) in Greece: 13 Years of Living with the Asian Tiger Mosquito. Parasitol. Res. 2018, 117, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratz, N.G. Critical Review of the Vector Status of Aedes Albopictus. Med. Vet. Entomol. 2004, 18, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paupy, C.; Delatte, H.; Bagny, L.; Corbel, V.; Fontenille, D. Aedes Albopictus, an Arbovirus Vector: From the Darkness to the Light. Microbes Infect. 2009, 11, 1177–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egid, B.R.; Coulibaly, M.; Dadzie, S.K.; Kamgang, B.; McCall, P.J.; Sedda, L.; Toe, K.H.; Wilson, A.L. Review of the Ecology and Behaviour of Aedes Aegypti and Aedes Albopictus in Western Africa and Implications for Vector Control. Curr. Res. Parasitol. Vector-Borne Dis. 2022, 2, 100074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouyer, J.; Yamada, H.; Pereira, R.; Bourtzis, K.; Vreysen, M.J.B. Phased Conditional Approach for Mosquito Management Using Sterile Insect Technique. Trends Parasitol. 2020, 36, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourtzis, K.; Dobson, S.L.; Xi, Z.; Rasgon, J.L.; Calvitti, M.; Moreira, L.A.; Bossin, H.C.; Moretti, R.; Baton, L.A.; Hughes, G.L.; et al. Harnessing Mosquito–Wolbachia Symbiosis for Vector and Disease Control. Acta Trop. 2014, 132, S150–S163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inácio da Silva, L.M.; Dezordi, F.Z.; Paiva, M.H.S.; Wallau, G.L. Systematic Review of Wolbachia Symbiont Detection in Mosquitoes: An Entangled Topic about Methodological Power and True Symbiosis. Pathogens 2021, 10, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werren, J.H.; Baldo, L.; Clark, M.E. Wolbachia: Master Manipulators of Invertebrate Biology. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2008, 6, 741–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werren, J.H.; Windsor, D.M. Wolbachia Infection Frequencies in Insects: Evidence of a Global Equilibrium? Proc. R. Soc. London. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 2000, 267, 1277–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werren, J.H.; Windsor, D.; Guo, L. Distribution of Wolbachia among Neotropical Arthropods. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 1995, 262, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilgenboecker, K.; Hammerstein, P.; Schlattmann, P.; Telschow, A.; Werren, J.H. How Many Species Are Infected with Wolbachia? €“ a Statistical Analysis of Current Data. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2008, 281, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinkins, S.P. Wolbachia and Cytoplasmic Incompatibility in Mosquitoes. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2004, 34, 723–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinkins, S. P.; Braig, H. R.; O’Neill, S.L. Wolbachia Superinfections and the Expression of Cytoplasmic Incompatibility. Proc. R. Soc. London. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 1995, 261, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iturbe-Ormaetxe, I.; Walker, T.; O’ Neill, S.L. Wolbachia and the Biological Control of Mosquito-borne Disease. EMBO Rep. 2011, 12, 508–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caragata, E.P.; Dutra, H.L.C.; Moreira, L.A. Exploiting Intimate Relationships: Controlling Mosquito-Transmitted Disease with Wolbachia. Trends Parasitol. 2016, 32, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Xi, Z.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Guo, Y.; Ren, D.; Wu, H.; Wang, X.; Chen, B.; Liu, Q. Identification and Molecular Characterization of Wolbachia Strains in Natural Populations of Aedes Albopictus in China. Parasit. Vectors 2020, 13, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afizah, An.; Roziah, A.; Nazni, W.; Lee, H. Detection of Wolbachia from Field Collected Aedes Albopictus Skuse in Malaysia. Indian J. Med. Res. 2015, 142, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, A.L. de; Magalhães, T.; Ayres, C.F.J. High Prevalence and Lack of Diversity of Wolbachia Pipientis in Aedes Albopictus Populations from Northeast Brazil. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2011, 106, 773–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baimai, V.; Kitrayapong, P.; O’Neill, S.L. Field Prevalence of Wolbachia in the Mosquito Vector Aedes Albopictus. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2002, 66, 108–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Rousset, F.; O’Neill, S. Phylogeny and PCR–Based Classification of Wolbachia Strains Using Wsp Gene Sequences. Proc. R. Soc. London. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 1998, 265, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortosa, P.; Charlat, S.; Labbé, P.; Dehecq, J.-S.; Barré, H.; Weill, M. Wolbachia Age-Sex-Specific Density in Aedes Albopictus: A Host Evolutionary Response to Cytoplasmic Incompatibility? PLoS One 2010, 5, e9700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiwatanaratanabutr, I.; Kittayapong, P. Effects of Crowding and Temperature on Wolbachia Infection Density among Life Cycle Stages of Aedes Albopictus. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2009, 102, 220–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldo, L.; Dunning Hotopp, J.C.; Jolley, K.A.; Bordenstein, S.R.; Biber, S.A.; Choudhury, R.R.; Hayashi, C.; Maiden, M.C.J.; Tettelin, H.; Werren, J.H. Multilocus Sequence Typing System for the Endosymbiont Wolbachia Pipientis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 7098–7110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaikevich, E.; Bogacheva, A.; Rakova, V.; Ganushkina, L.; Ilinsky, Y. Wolbachia Symbionts in Mosquitoes: Intra- and Intersupergroup Recombinations, Horizontal Transmission and Evolution. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2019, 134, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuchuy, A.; Rodriguero, M.S.; Ferrari, W.; Ciota, A.T.; Kramer, L.D.; Micieli, M. V. Biological Characterization of Aedes Albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) in Argentina: Implications for Arbovirus Transmission. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 5041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blagrove, M.S.C.; Arias-Goeta, C.; Failloux, A.-B.; Sinkins, S.P. Wolbachia Strain w Mel Induces Cytoplasmic Incompatibility and Blocks Dengue Transmission in Aedes Albopictus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2012, 109, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blagrove, M.S.C.; Arias-Goeta, C.; Di Genua, C.; Failloux, A.-B.; Sinkins, S.P. A Wolbachia WMel Transinfection in Aedes Albopictus Is Not Detrimental to Host Fitness and Inhibits Chikungunya Virus. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2013, 7, e2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, M.V.; Herd, C.S.; Ant, T.H.; Murdochy, S.M.; Sinkins, S.P. Wolbachia Strain WAu Efficiently Blocks Arbovirus Transmission in Aedes Albopictus. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2020, 14, e0007926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MORETTI, R.; CALVITTI, M. Male Mating Performance and Cytoplasmic Incompatibility in a w Pip Wolbachia Trans-infected Line of Aedes Albopictus ( Stegomyia Albopicta ). Med. Vet. Entomol. 2013, 27, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Zheng, X.; Xi, Z.; Bourtzis, K.; Gilles, J.R.L. Combining the Sterile Insect Technique with the Incompatible Insect Technique: I-Impact of Wolbachia Infection on the Fitness of Triple- and Double-Infected Strains of Aedes Albopictus. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0121126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Zhang, D.; Li, Y.; Yang, C.; Wu, Y.; Liang, X.; Liang, Y.; Pan, X.; Hu, L.; Sun, Q.; et al. Incompatible and Sterile Insect Techniques Combined Eliminate Mosquitoes. Nature 2019, 572, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caputo, B.; Moretti, R.; Virgillito, C.; Manica, M.; Lampazzi, E.; Lombardi, G.; Serini, P.; Pichler, V.; Beebe, N.W.; della Torre, A.; et al. A Bacterium against the Tiger: Further Evidence of the Potential of Noninundative Releases of Males with Manipulated Wolbachia Infection in Reducing Fertility of Aedes Albopictus Field Populations in Italy. Pest Manag. Sci. 2023, 79, 3167–3176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucati, F.; Delacour, S.; Palmer, J.R.B.; Caner, J.; Oltra, A.; Paredes-Esquivel, C.; Mariani, S.; Escartin, S.; Roiz, D.; Collantes, F.; et al. Multiple Invasions, Wolbachia and Human-Aided Transport Drive the Genetic Variability of Aedes Albopictus in the Iberian Peninsula. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 20682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amraoui, F.; Failloux, A.-B. Chikungunya: An Unexpected Emergence in Europe. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2016, 21, 146–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maria, A.T.; Maquart, M.; Makinson, A.; Flusin, O.; Segondy, M.; Leparc-Goffart, I.; Le Moing, V.; Foulongne, V. Zika Virus Infections in Three Travellers Returning from South America and the Caribbean Respectively, to Montpellier, France, December 2015 to January 2016. Eurosurveillance 2016, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gjenero-Margan, I.; Aleraj, B.; Krajcar, D.; Lesnikar, V.; Klobučar, A.; Pem-Novosel, I.; Kurečić-Filipović, S.; Komparak, S.; Martić, R.; Đuričić, S.; et al. Autochthonous Dengue Fever in Croatia, August–September 2010. Eurosurveillance 2011, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzon, L.; Gobbi, F.; Capelli, G.; Montarsi, F.; Martini, S.; Riccetti, S.; Sinigaglia, A.; Pacenti, M.; Pavan, G.; Rassu, M.; et al. Autochthonous Dengue Outbreak in Italy 2020: Clinical, Virological and Entomological Findings. J. Travel Med. 2021, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasello, D.; Schlagenhauf, P. Chikungunya and Dengue Autochthonous Cases in Europe, 2007–2012. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2013, 11, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, E.A.; Gallian, P.; de Lamballerie, X.; Charrel, R.N. First Cases of Autochthonous Dengue Fever and Chikungunya Fever in France: From Bad Dream to Reality! Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2010, 16, 1702–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roiz, D.; Boussès, P.; Simard, F.; Paupy, C.; Fontenille, D. Autochthonous Chikungunya Transmission and Extreme Climate Events in Southern France. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2015, 9, e0003854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calba, C.; Guerbois-Galla, M.; Franke, F.; Jeannin, C.; Auzet-Caillaud, M.; Grard, G.; Pigaglio, L.; Decoppet, A.; Weicherding, J.; Savaill, M.-C.; et al. Preliminary Report of an Autochthonous Chikungunya Outbreak in France, July to September 2017. Eurosurveillance 2017, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venturi, G.; Di Luca, M.; Fortuna, C.; Remoli, M.E.; Riccardo, F.; Severini, F.; Toma, L.; Del Manso, M.; Benedetti, E.; Caporali, M.G.; et al. Detection of a Chikungunya Outbreak in Central Italy, August to September 2017. Eurosurveillance 2017, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagnarelli, P.; Marinelli, K.; Trotta, D.; Monachetti, A.; Tavio, M.; Del Gobbo, R.; Capobianchi, M.R.; Menzo, S.; Nicoletti, L.; Magurano, F.; et al. Human Case of Autochthonous West Nile Virus Lineage 2 Infection in Italy, September 2011. Eurosurveillance 2011, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietsch, C.; Michalski, D.; Münch, J.; Petros, S.; Bergs, S.; Trawinski, H.; Lübbert, C.; Liebert, U.G. Autochthonous West Nile Virus Infection Outbreak in Humans, Leipzig, Germany, August to September 2020. Eurosurveillance 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, J.; Bachmann, F.; Choi, M.; Kurvits, L.; Schmidt, M.L.; Bergfeld, L.; Meier, I.; Zuchowski, M.; Werber, D.; Hofmann, J.; et al. Autochthonous West Nile Virus Infection in Germany: Increasing Numbers and a Rare Encephalitis Case in a Kidney Transplant Recipient. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2022, 69, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlaskamp, D.R.; Thijsen, S.F.; Reimerink, J.; Hilkens, P.; Bouvy, W.H.; Bantjes, S.E.; Vlaminckx, B.J.; Zaaijer, H.; van den Kerkhof, H.H.; Raven, S.F.; et al. First Autochthonous Human West Nile Virus Infections in the Netherlands, July to August 2020. Eurosurveillance 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalli, L.; Grard, G.; Beck, C.; Gallian, P.; L’Ambert, G.; Desvaux, S.; Jourdan, M.; Ortmans, C.; Paty, M.-C.; Franke, F. West Nile Virus Infections in France, July to November 2018. Eur. J. Public Health 2019, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laidoudi, Y.; Durand, G.; Watier-Grillot, S.; Dessimoulie, A.-S.; Labarde, C.; Normand, T.; Andréo, V.; Guérin, P.; Grard, G.; Davoust, B. Evidence of Antibodies against the West Nile Virus and the Usutu Virus in Dogs and Horses from the Southeast of France. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2023, 2023, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J.J.; Haussig, J.M.; Aberle, S.W.; Pervanidou, D.; Riccardo, F.; Sekulić, N.; Bakonyi, T.; Gossner, C.M. Epidemiology of Human West Nile Virus Infections in the European Union and European Union Enlargement Countries, 2010 to 2018. Eurosurveillance 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillepold, K.; Rocklöv, J.; Liu-Helmersson, J.; Sewe, M.; Semenza, J.C. More Arboviral Disease Outbreaks in Continental Europe Due to the Warming Climate? J. Travel Med. 2019, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semenza, J.C.; Suk, J.E. Vector-Borne Diseases and Climate Change: A European Perspective. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2018, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehorn, J.; Yacoub, S. Global Warming and Arboviral Infections. Clin. Med. (Northfield. Il). 2019, 19, 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, N.; Petrić, D.; Zgomba, M.; Boase, C.; Madon, M.B.; Dahl, C.; Kaiser, A. Mosquitoes. Identification, Biology and Control, 3rd ed.; Springer: Switzerland, 2020; ISBN 9783030116224. [Google Scholar]

- Darsie, R.F.; Samanidou-Voyadjoglou, A. Keys for the Identification of the Mosquitoes of Greece. J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc. 1997, 13, 247–254. [Google Scholar]

- Samanidou-Voyadjoglou, A.; Harbach, R.E. Keys to the Adult Female Mosquitoes (Culicidae) of Greece. Eur. Mosq. Bull. 2001, 10, 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, J. DNA Protocols for Plants. In Molecular Techniques in Taxonomy; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 1991; pp. 283–293. [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto, J.M.; Feinstein, J.; Rasgon, J.L. Wolbachia Infections in the Cimicidae: Museum Specimens as an Untapped Resource for Endosymbiont Surveys. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 3161–3167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanner, R.; Fugate, M. Branchiopod Phylogenetic Reconstruction from 12s RDNA Sequence Data. J. Crustac. Biol. 1997, 17, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kounatidis, I.; Papadopoulos, N.; Bourtzis, K.; Mavragani-Tsipidou, P. Genetic and Cytogenetic Analysis of the Fruit Fly Rhagoletis Cerasi (Diptera: Tephritidae). Genome 2008, 51, 479–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustinos, A.A.; Santos-Garcia, D.; Dionyssopoulou, E.; Moreira, M.; Papapanagiotou, A.; Scarvelakis, M.; Doudoumis, V.; Ramos, S.; Aguiar, A.F.; Borges, P.A. V.; et al. Detection and Characterization of Wolbachia Infections in Natural Populations of Aphids: Is the Hidden Diversity Fully Unraveled? PLoS One 2011, 6, e28695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruskal, W.H.; Wallis, W.A. Use of Ranks in One-Criterion Variance Analysis. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1952, 47, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, O.J. Multiple Comparisons Using Rank Sums. Technometrics 1964, 6, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armbruster, P.; Damsky, W.E.; Giordano, R.; Birungi, J.; Munstermann, L.E.; Conn, J.E. Infection of New- and Old-World Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) by the intracellular parasite Wolbachia: implications for host mitochondrial DNA evolution. J. Med. Entomol. 2003, 40, 356–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldo, L.; Werren, J.H. Revisiting Wolbachia Supergroup Typing Based on WSP: Spurious Lineages and Discordance with MLST. Curr. Microbiol. 2007, 55, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutton, T.J.; Sinkins, S.P. Strain-Specific Quantification of Wolbachia Density in Aedes Albopictus and Effects of Larval Rearing Conditions. Insect Mol. Biol. 2004, 13, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manni, M.; Guglielmino, C.R.; Scolari, F.; Vega-Rúa, A.; Failloux, A.B.; Somboon, P.; Lisa, A.; Savini, G.; Bonizzoni, M.; Gomulski, L.M.; et al. Genetic Evidence for a Worldwide Chaotic Dispersion Pattern of the Arbovirus Vector, Aedes Albopictus. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2017, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.; Chung, J.; Robinson, K.L.; Schmidt, T.L.; Ross, P.A.; Liang, J.; Hoffmann, A.A. Sex-Specific Distribution and Classification of Wolbachia Infections and Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups in Aedes Albopictus from the Indo-Pacific. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2022, 16, e0010139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ENGELSTÄDTER, J.; HAMMERSTEIN, P.; HURST, G.D.D. The Evolution of Endosymbiont Density in Doubly Infected Host Species. J. Evol. Biol. 2007, 20, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WIWATANARATANABUTR, S.; KITTAYAPONG, P. Effects of Temephos and Temperature on Wolbachia Load and Life History Traits of Aedes Albopictus. Med. Vet. Entomol. 2006, 20, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

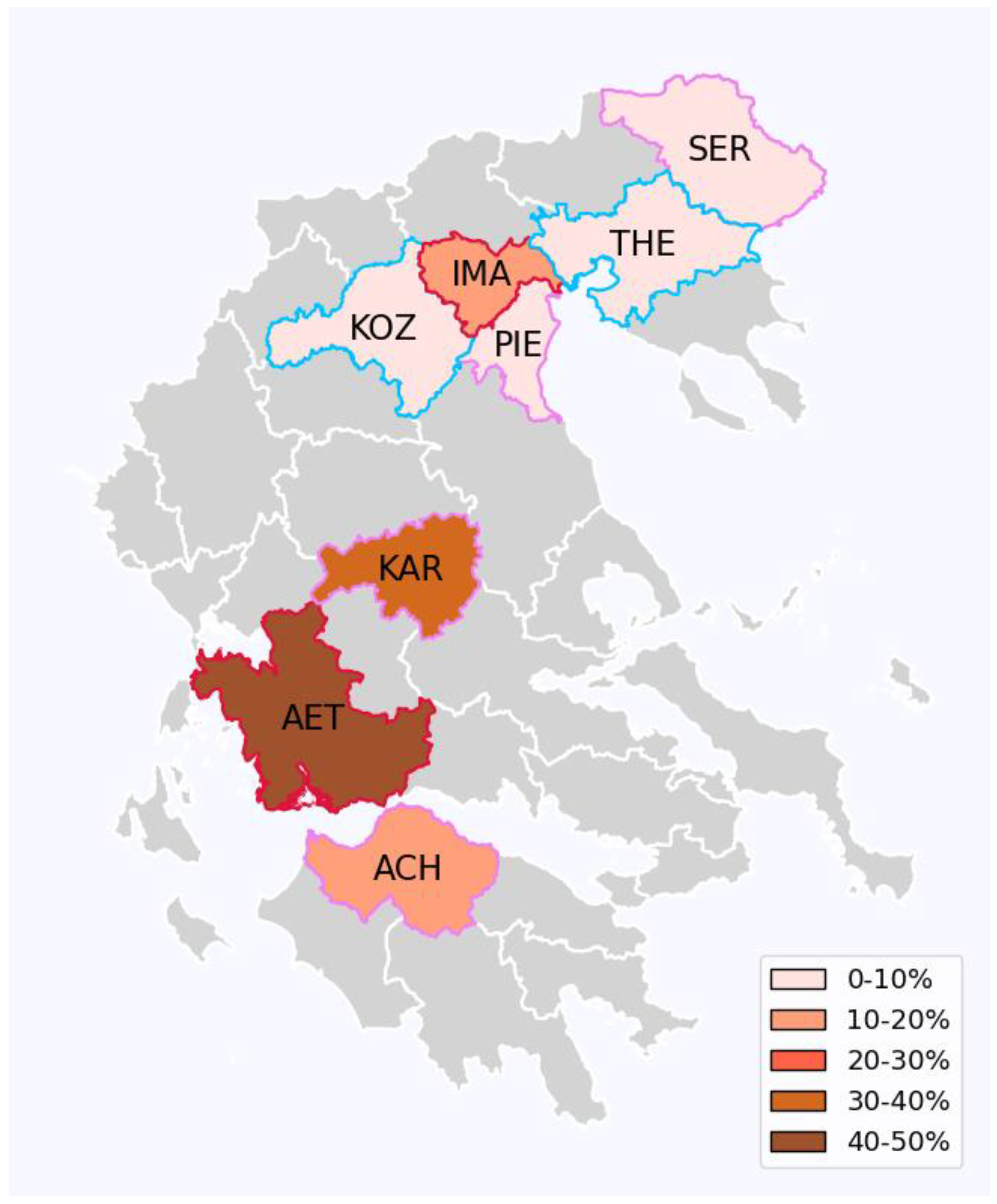

| Prefecture (abbreviation). | Trap coordinates | Sampling dates | Collected mosquitoes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Achaea (ACH) | 38.314695/ 21.814237 | 30/08 | 10 |

| Aetolia-Acarnania (AET) | 38.61610755/ 21.3825769;38.39032018/ 21.85072874 | 12/07; 11/08 | 15 |

| Imathia (IMA) | 40.536217/ 22.20227 | 26/08 | 9 |

| Karditsa (KAR) | 39.397834/ 22.070087;39.37078032/ 21.93258031 | 27/7; 7/9; 21/9 | 27 |

| Kozani (KOZ) | 40.312092/ 21.822304 | 16/8; 27/9 | 19 |

| Pieria (PIE) | 40.237544/ 22.582148 | 30/8 | 13 |

| Serres (SER) | 41.205796/ 23.074921 | 13/7 | 4 |

| Thessaloniki (THE) | 40.64858/ 22.954067 | 16/9 | 8 |

| Prefecture (abbreviation) | No of samples/Sex | Wolbachia prevalence | Double infection (wAlbA+wAlbB) | Single infection (wAlbB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Achaea (ACH) | 5♂,5♀ | 90% (9/10) | 89% (4♂,4♀) | 11% (1♂) |

| Aetolia-Acarnania (AET) | 9♂,6♀ | 87% (13/15) | 54% (5♂,2♀) | 46% (3♂,3♀) |

| Imathia (IMA) | 9♀ | 100% (9/9) | 89% (8♀) | 11% (1♀) |

| Karditsa (KAR) | 14♂,13♀ | 93% (25/27) | 68% (4♂,13♀) | 32% (8♂) |

| Kozani (KOZ) | 19♀ | 100% (19/19) | 100% (19♀) | 0% |

| Pieria (PIE) | 13♀ | 100% (13/13) | 100% (13♀) | 0% |

| Serres (SER) | 4♀ | 100% (4/4) | 100% (4♀) | 0% |

| Thessaloniki (THE) | 3♂,5♀ | 100% (8/8) | 100% (3♂,5♀) | 0% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).