Submitted:

19 December 2023

Posted:

20 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Sample Collection and DNA Extraction

Targeted Resequencing of FANCD2 using Next Generation Sequencing (NGS):

Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) Data Analysis

Primary Analysis

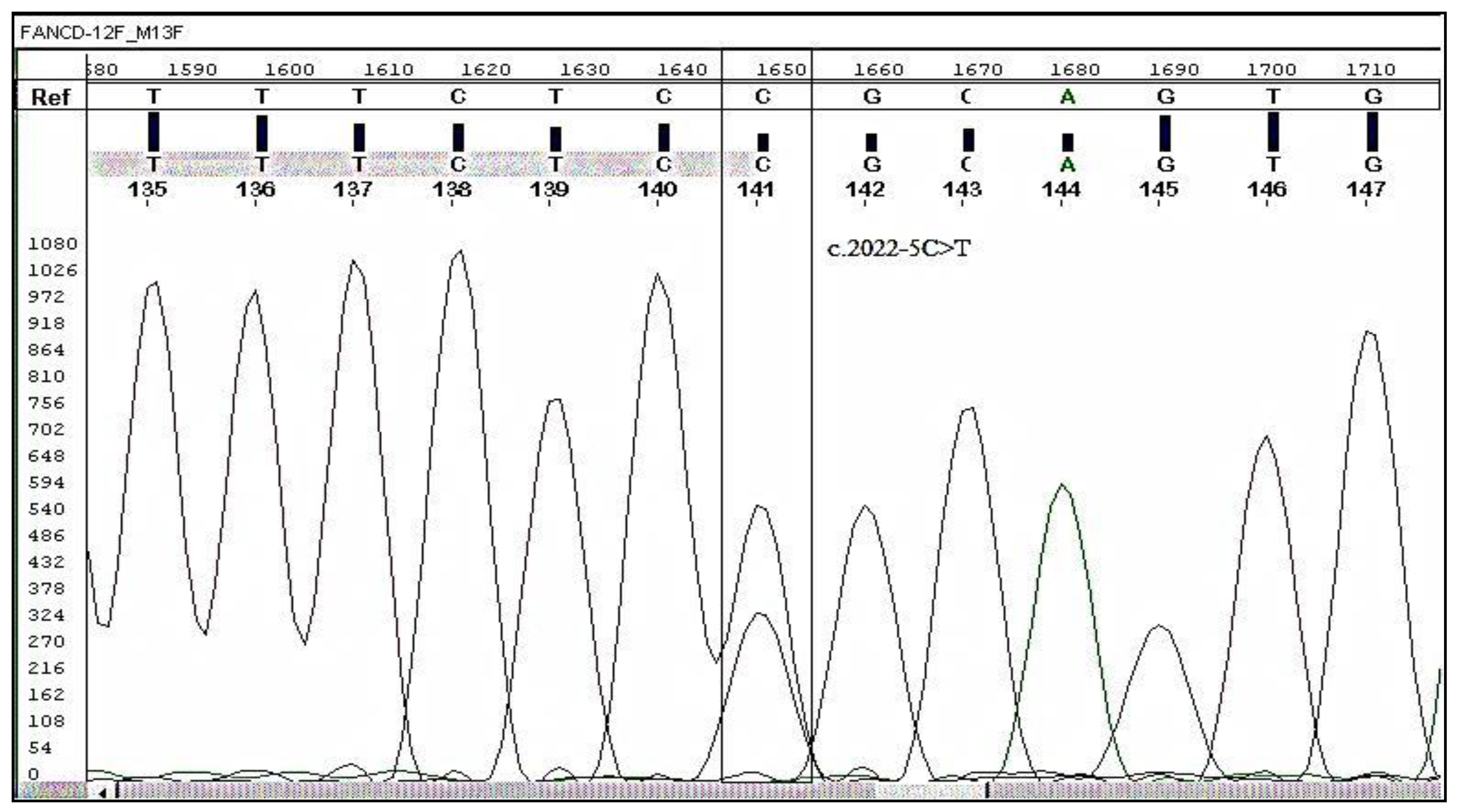

Validation of Mutation by Sanger Sequencing

Statistical Analysis of Patient Clinical Data

3. Results

Next Generation Sequencing (NGS)

Validation by Sanger Sequencing

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Funding Information

Acknowledgements

Research Ethics’ Statements and Approval of the study

Conflict of Interest

References

- D'Andrea, A. D., & Grompe, M. (2003). The Fanconi anaemia/BRCA pathway. *Nature Reviews Cancer*, 3(1), 23-34. [CrossRef]

- Absar, M., Mahmood, A., Akhtar, T., Basit, S., Ramzan, K., Jameel, A., ... & Iqbal, Z. (2020). Whole exome sequencing identifies a novel FANCD2 gene splice site mutation associated with disease progression in chronic myeloid leukemia: Implication in targeted therapy of advanced phase CML. *Pakistan Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences*, 33(3(Special)), 1419-1426. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlAsiri, S., Basit, S., Wood-Trageser, M., Yatsenko, S. A., Jeffries, E. P., Surti, U., ... & Haque, M. F.-U. (2015). Exome sequencing reveals MCM8 mutation underlies ovarian failure and chromosomal instability. *Journal of Clinical Investigation*, 125(1), 258-262. [CrossRef]

- Ali, M. A. (2016). Chronic Myeloid Leukemia in the Era of Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors: An Evolving Paradigm of Molecularly Targeted Therapy. Molecular Diagnosis & Therapy, 20(4), 315-333. [CrossRef]

- Apperley, J. F. (2015). Chronic myeloid leukaemia. The Lancet, 385(9976), 1447-1459. [CrossRef]

- Baccarani, M., Castagnetti, F., Gugliotta, G., & Rosti, G. (2015). A review of the European LeukemiaNet recommendations for the management of CML. *Annals of Hematology*, 94(Suppl 2), S141-S147. [CrossRef]

- Baccarani, M., Deininger, M. W., Rosti, G., Hochhaus, A., Soverini, S., Apperley, J. F., ... & Hehlmann, R. (2013). European LeukemiaNet recommendations for the management of chronic myeloid leukemia: 2013. *Blood*, 122(6), 872-884. [CrossRef]

- Branford, S., Wang, P., Yeung, D. T., Thomson, D., Purins, A., Wadham, C., ... & Hughes, T. P. (2018). Integrative genomic analysis reveals cancer-associated mutations at diagnosis of CML in patients with high-risk disease. *Blood*, 132, 948–961. [CrossRef]

- Carson, A. R., Smith, E. N., Matsui, H., Brækkan, S. K., Jepsen, K., Hansen, J.-B., ... & Frazer, A. K. (2014). Effective filtering strategies to improve data quality from population-based whole exome sequencing studies. *BMC Bioinformatics*, 15, 125. [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekharappa SC, Chinn SB, Donovan FX, Chowdhury NI, Kamat A, Adeyemo AA, Thomas JW, Vemulapalli M, Hussey CS, Reid HH, Mullikin JC, Wei Q, Sturgis EM. Assessing the spectrum of germline variation in Fanconi anemia genes among patients with head and neck carcinoma before age 50. Cancer. 2017 Oct 15;123(20):3943-3954. Epub 2017 Jul 5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chirnomas D, Taniguchi T, de la Vega M, et al. Chemosensitization to cisplatin by inhibitors of the Fanconi anemia/BRCA pathway. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5(4):952-961. [CrossRef]

- Chronic granulocytic leukaemia: comparison of radiotherapy and busulphan therapy. Report of the Medical Research Council's working party for therapeutic trials in leukaemia. (1968). British Medical Journal, 1(5586), 201-208. [CrossRef]

- Cornwell, M. J. , Thomson, G. J., Coates, J., Belotserkovskaya, R., Waddell, I. D., Jackson, S. P., & Galanty, Y. (2019). Small-Molecule Inhibition of UBE2T/FANCL-Mediated Ubiquitylation in the Fanconi Anemia Pathway. ACS chemical biology, 14(10), 2148–2154. [CrossRef]

- Cortes, E. J. , Lipton, J. H., Miller, C. B., Ailawadhi, S., Akard, L., Pinilla-Ibarz, J.,... & Mauro, M. J. (2012). Change in Chronic Low-Grade Nonhematologic Adverse Events (AEs) and Quality of Life (QoL) in Adult Patients (pts) with Philadelphia Chromosome–Positive (Ph+) Chronic Myeloid Leukemia in Chronic Phase (CML-CP) Switched From Imatinib (IM) to Nilotinib (NIL). *Blood*, 120(21), 3782.

- Cortes, J. E. , Talpaz, M., O'Brien, S., Faderl, S., Garcia-Manero, G., Ferrajoli, A.,... Kantarjian, H. M. (2006). Staging of chronic myeloid leukemia in the imatinib era: an evaluation of the World Health Organization proposal. Cancer, 106(6), 1306-1315. [CrossRef]

- Dan, C. , Pei, H., Zhang, B. et al. Fanconi anemia pathway and its relationship with cancer. GENOME INSTAB. DIS. 2, 175–183 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Dong, H., Nebert, D. W., Bruford, E. A., Thompson, D. C., Joenje, H., & Vasiliou, V. (2015). Update of the human and mouse Fanconi anemia genes. Human Genomics, 9, 32. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng L, Jin F. Expression and prognostic significance of Fanconi anemia group D2 protein and breast cancer type 1 susceptibility protein in familial and sporadic breast cancer. Oncol Lett. 2019 Apr;17(4):3687-3700. Epub 2019 Feb 18. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gnirke, A. , Melnikov, A., Maguire, J., Rogov, P., LeProust, E. M., Brockman, W.,... & Nusbaum, C. (2009). Solution hybrid selection with ultra-long oligonucleotides for massively parallel targeted sequencing. *Nature Biotechnology*, 27(2), 182-189. [CrossRef]

- Goodyear, E. , Krleza-Jeric, M. D., & Lemmens, K. (2007). The Declaration of Helsinki. *BMJ*, 335, 624–625. [CrossRef]

- Hasford, J. , Baccarani, M., Hoffmann, V., Guilhot, J., Saussele, S., Rosti, G.,... & Hehlmann, R. (2011). Predicting complete cytogenetic response and subsequent progression-free survival in 2060 patients with CML on imatinib treatment: the EUTOS score. *Blood*, 118(3), 686-692. [CrossRef]

- Hasford, J. , Pfirrmann, M., Hehlmann, R., Allan, N. C., Baccarani, M., Kluin-Nelemans, J. C.,... & Ansari, H. (1998). Writing Committee for the Collaborative CML Prognostic Factors Project Group. A new prognostic score for survival of patients with chronic myeloid leukemia treated with interferon alfa. *Journal of the National Cancer Institute*, 90(11), 850–858. [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, E. , & Kantarjian, H. (2020). Chronic myeloid leukemia: 2020 update on diagnosis, therapy and monitoring. American Journal of Hematology, 95(6), 691-709. [CrossRef]

- Joo W, Xu G, Persky NS, Smogorzewska A, Rudge DG, Buzovetsky O,... & Pavletich NP. (2011). Structure of the FANCI-FANCD2 complex: insights into the Fanconi anemia DNA repair pathway. *Science*, 333(6040), 312-316. [CrossRef]

- Joshi S, Campbell S, Lim JY, McWeeney S, Krieg A, Bean Y, Pejovic N, Mhawech-Fauceglia P, Pejovic T. Subcellular localization of FANCD2 is associated with survival in ovarian carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2020 Feb 25;11(8):775-783. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalb R, Neveling K, Hoehn H, Schneider H, Linka Y, Batish SD, Hunt C, Berwick M, Callen E, Surralles J, Casado JA, Bueren J, Dasi A, Soulier J, Gluckman E, Zwaan CM, van Spaendonk R, Pals G, de Winter JP, Joenje H, Grompe M, Auerbach AD, Hanenberg H, Schindler D. (2007). Hypomorphic mutations in the gene encoding a key Fanconi anemia protein, FANCD2, sustain a significant group of FA-D2 patients with severe phenotype. *American Journal of Human Genetics*, 80(5), 895-910. [CrossRef]

- Landais, I., Hiddingh, S., McCarroll, M., Yang, C., Sun, A., Turker, M. S., Snyder, J. P., & Hoatlin, M. E. (2009). Monoketone analogs of curcumin, a new class of Fanconi anemia pathway inhibitors. Molecular cancer, 8, 133. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei LC, Yu VZ, Ko JMY, Ning L, Lung ML. FANCD2 Confers a Malignant Phenotype in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma by Regulating Cell Cycle Progression. Cancers (Basel). 2020 Sep 7;12(9):2545. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis AG, Flanagan J, Marsh A, Pupo GM, Mann G, Spurdle AB, Lindeman GJ, Visvader JE, Brown MA, Chenevix-Trench G; Kathleen Cuningham Foundation Consortium for Research into Familial Breast Cancer. (2005). Mutation analysis of FANCD2, BRIP1/BACH1, LMO4 and SFN in familial breast cancer. *Breast Cancer Research*, 7(6), R1005-16. [CrossRef]

- Li L, Tan W, Deans AJ. Structural insight into FANCI-FANCD2 monoubiquitination. Essays Biochem. 2020 Oct 26;64(5):807-817. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li N, Ding L, Li B, Wang J, D'Andrea AD, Chen J. (2018). Functional analysis of Fanconi anemia mutations in China. *Experimental Hematology*, 66, 32-41.e8. [CrossRef]

- Liang CC, Li Z, Lopez-Martinez D, Nicholson WV, Vénien-Bryan C, Cohn MA. The FANCD2-FANCI complex is recruited to DNA interstrand crosslinks before monoubiquitination of FANCD2. Nat Commun. 2016 Jul 13;7:12124. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu W, Palovcak A, Li F, Zafar A, Yuan F, Zhang Y. Fanconi anemia pathway as a prospective target for cancer intervention. Cell Biosci. 2020;10:39. Published 2020 Mar 16. [CrossRef]

- MacKay C, Déclais AC, Lundin C, Agostinho A, Deans AJ, MacArtney TJ,... & Rouse J. (2010). Identification of KIAA1018/FAN1, a DNA repair nuclease recruited to DNA damage by monoubiquitinated FANCD2. *Cell*, 142(1), 65-76. [CrossRef]

- Mahon, F. X. , & Etienne, G. (2014). Deep molecular response in chronic myeloid leukemia: the new goal of therapy? *Clinical Cancer Research*, 20(2), 310-322. [CrossRef]

- Mani C, Tripathi K, Chaudhary S, Somasagara RR, Rocconi RP, Crasto C, Reedy M, Athar M, Palle K. Hedgehog/GLI1 Transcriptionally Regulates FANCD2 in Ovarian Tumor Cells: Its Inhibition Induces HR-Deficiency and Synergistic Lethality with PARP Inhibition. Neoplasia. 2021 Sep;23(9):1002-1015. Epub 2021 Aug 8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantere T, Tervasmäki A, Nurmi A, Rapakko K, Kauppila S, Tang J, Schleutker J, Kallioniemi A, Hartikainen JM, Mannermaa A, Nieminen P, Hanhisalo R, Lehto S, Suvanto M, Grip M, Jukkola-Vuorinen A, Tengström M, Auvinen P, Kvist A, Borg Å, Blomqvist C, Aittomäki K, Greenberg RA, Winqvist R, Nevanlinna H, Pylkäs K. Case-control analysis of truncating mutations in DNA damage response genes connects TEX15 and FANCD2 with hereditary breast cancer susceptibility. Sci Rep. 2017 Apr 6;7(1):681. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meetei AR, de Winter JP, Medhurst AL, Wallisch M, Waisfisz Q, van de Vrugt HJ,... & Wang, W. (2003). A novel ubiquitin ligase is deficient in Fanconi anemia. *Nature Genetics*, 35(2), 165-170. [CrossRef]

- Miao, H. , Ren, Q., Li, H., Zeng, M., Chen, D., Xu, C., Chen, Y., & Wen, Z. (2022). Comprehensive analysis of the autophagy-dependent ferroptosis-related gene FANCD2 in lung adenocarcinoma. BMC cancer, 22(1), 225. [CrossRef]

- Moes-Sosnowska J, Rzepecka IK, Chodzynska J, Dansonka-Mieszkowska A, Szafron LM, Balabas A, Lotocka R, Sobiczewski P, Kupryjanczyk J. Clinical importance of FANCD2, BRIP1, BRCA1, BRCA2 and FANCF expression in ovarian carcinomas. Cancer Biol Ther. 2019;20(6):843-854. Epub 2019 Mar 1. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. ClinVar; [VCV000218824.22]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/variation/VCV000218824.22 (accessed Oct. 25, 2022).

- Niraj, J., Färkkilä, A., & D'Andrea, A. D. (2019). The Fanconi Anemia Pathway in Cancer. Annual review of cancer biology, 3, 457–478. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osman, A. E. G. , & Deininger, M. W. (2021). Chronic Myeloid Leukemia: Modern therapies, current challenges, and future directions. Blood Reviews, 49, 100825. [CrossRef]

- Quintás-Cardama, A. , & Cortes, J. (2009). Molecular biology of bcr-abl1-positive chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood, 113(8), 1619-1630. [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. (2012). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. ISBN 3-900051-07-0. URL http://www.R-project.org/.

- Senapati, J., Jabbour, E., Kantarjian, H., & Short, N. J. (2023). Pathogenesis and management of accelerated and blast phases of chronic myeloid leukemia. Leukemia, 37(1), 5–17. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senapati, J. , Sasaki, K., Issa, G. C., Lipton, J. H., Radich, J. P., Jabbour, E., & Kantarjian, H. M. (2023). Management of chronic myeloid leukemia in 2023 - common ground and common sense. Blood cancer journal, 13(1), 58. [CrossRef]

- Narlı Özdemir, Z. , Kılıçaslan, N. A., Yılmaz, M., & Eşkazan, A. E. (2023). Guidelines for the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia from the NCCN and ELN: differences and similarities. International journal of hematology, 117(1), 3–15. [CrossRef]

- Eden, R. E. , & Coviello, J. M. (2023). Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing.

- Iurlo, A. , Cattaneo, D., Consonni, D., Castagnetti, F., Miggiano, M. C., Binotto, G., Bonifacio, M., Rege-Cambrin, G., Tiribelli, M., Lunghi, F., Gozzini, A., Pregno, P., Abruzzese, E., Capodanno, I., Bucelli, C., Pizzuti, M., Artuso, S., Iezza, M., Scalzulli, E., La Barba, G., … Breccia, M. (2023). Treatment discontinuation following low-dose TKIs in 248 chronic myeloid leukemia patients: Updated results from a campus CML real-life study. Frontiers in pharmacology, 14, 1154377. [CrossRef]

- Boucher, L. , Sorel, N., Desterke, C., Chollet, M., Rozalska, L., Gallego Hernanz, M. P., Cayssials, E., Raimbault, A., Bennaceur-Griscelli, A., Turhan, A. G., & Chomel, J. C. (2023). Deciphering Potential Molecular Signatures to Differentiate Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) with BCR::ABL1 from Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML) in Blast Crisis. International journal of molecular sciences, 24(20), 15441. [CrossRef]

- Busch, C. , Mulholland, T., Zagnoni, M., Dalby, M., Berry, C., & Wheadon, H. (2023). Overcoming BCR::ABL1 dependent and independent survival mechanisms in chronic myeloid leukaemia using a multi-kinase targeting approach. Cell communication and signaling : CCS, 21(1), 342. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, N. (2023). [Rinsho ketsueki] The Japanese journal of clinical hematology, 64(9), 981–987.

- Shen Y, Zhang J, Yu H, Fei P. Advances in the understanding of Fanconi Anemia Complementation Group D2 Protein (FANCD2) in human cancer. Cancer Cell Microenviron. 2015;2(4):e986. Epub 2015 Sep 7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, R.L., Miller, K.D., & Jemal, A. (2017). Cancer Statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin, 67(1), 7-30. Epub 2017 Jan 5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smogorzewska A, Desetty R, Saito TT, Schlabach M, Lach FP, Sowa ME, Clark AB, Kunkel TA, Harper JW, Colaiácovo MP, Elledge SJ. A genetic screen identifies FAN1, a Fanconi anemia-associated nuclease necessary for DNA interstrand crosslink repair. Mol Cell. 2010 Jul 9;39(1):36-47. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sokal, J. E. , Cox, E. B., Baccarani, M., Tura, S., Gomez, G. A., Robertson, J. E.,... & Cervantes, F. (1984). Prognostic discrimination in "good-risk" chronic granulocytic leukemia. *Blood*, 63(4), 789-799. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, L. H. , Hinz, J. M., Yamada, N. A., & Jones, N. J. (2005). How Fanconi anemia proteins promote the four Rs: replication, recombination, repair, and recovery. *Environmental and Molecular Mutagenesis*, 45(2-3), 128–142. [CrossRef]

- Tsiatis, A. C. , Norris-Kirby, A., Rich, R. G., Hafez, M. J., Gocke, C. D., Eshleman, J. R.,... & Murphy, K. M. (2010). Comparison of Sanger sequencing, pyrosequencing, and melting curve analysis for the detection of KRAS mutations: diagnostic and clinical implications. *Journal of Molecular Diagnostics*, 12(4), 425-432. [CrossRef]

- Valeri A, Río P, Agirre X, Prosper F, Bueren JA. (2012). Unraveling the role of FANCD2 in chronic myeloid leukemia. *Leukemia*, 26(6), 1447-1448. [CrossRef]

- van Twest S, Murphy VJ, Hodson C, Tan W, Swuec P, O'Rourke JJ,... & Deans AJ. (2017). Mechanism of Ubiquitination and Deubiquitination in the Fanconi Anemia Pathway. *Molecular Cell*, 65(2), 247-259. [CrossRef]

- Venkitaraman, A. R. (2004). Tracing the network connecting BRCA and Fanconi anaemia proteins. Nature Reviews Cancer, 4(4), 266-276. [CrossRef]

- Wang AT, Smogorzewska A. (2015). SnapShot: Fanconi anemia and associated proteins. *Cell*, 160(1-2), 354-354.e1. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Andreassen PR, D'Andrea AD. (2004). Functional interaction of monoubiquitinated FANCD2 and BRCA2/FANCD1 in chromatin. *Molecular Cell Biology*, 24(13), 5850-5862. [CrossRef]

- Williams SA, Wilson JB, Clark AP, Mitson-Salazar A, Tomashevski A, Ananth S, Glazer PM, Semmes OJ, Bale AE, Jones NJ, Kupfer GM. Functional and physical interaction between the mismatch repair and FA-BRCA pathways. Hum Mol Genet. 2011 Nov 15;20(22):4395-410. Epub 2011 Aug 24. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Medical Association. (2007). Declaration of Helsinki 2007. Available online: www.wma.net/e/ethicsunit/helsinki.htm (accessed on 11 February 2021).

- Xu S, Zhao F, Liang Z, Feng H, Bao Y, Xu W, Zhao C, Qin G. Expression of FANCD2 is associated with prognosis in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2019 Sep 1;12(9):3465-3473. [PubMed]

- Xu, J. , Wu, M., Sun, Y., Zhao, H., Wang, Y., & Gao, J. (2020). Identifying Dysregulated lncRNA-Associated ceRNA Network Biomarkers in CML Based on Dynamical Network Biomarkers. *BioMed Research International*, 2020, 5189549.

- Yoshimaru, R., & Minami, Y. (2023). Genetic Landscape of Chronic Myeloid Leukemia and a Novel Targeted Drug for Overcoming Resistance. International journal of molecular sciences, 24(18), 13806. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, J. E. , Kim, S. H., Kong, M., Kim, H. R., Yoon, S., Kee, K. M., Kim, J. A., Kim, D. H., Park, S. Y., Park, J. H., Kim, H., No, K. T., Lee, H. W., Gee, H. Y., Hong, S., Guan, K. L., Roe, J. S., Lee, H., Kim, D. W., & Park, H. W. (2023). Targeting FLT3-TAZ signaling to suppress drug resistance in blast phase chronic myeloid leukemia. Molecular cancer, 22(1), 177. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. Y., Zhao, H. F., Zhang, Y. L., & Song, Y. P. (2023). Zhongguo shi yan xue ye xue za zhi, 31(3), 649–653.

- Telliam, G. , Desterke, C., Imeri, J., M'kacher, R., Oudrhiri, N., Balducci, E., Fontaine-Arnoux, M., Acloque, H., Bennaceur-Griscelli, A., & Turhan, A. G. (2023). Modeling Global Genomic Instability in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML) Using Patient-Derived Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs). Cancers, 15(9), 2594. [CrossRef]

- Leung, W. , Baxley, R. M., Traband, E., Chang, Y. C., Rogers, C. B., Wang, L., Durrett, W., Bromley, K. S., Fiedorowicz, L., Thakar, T., Tella, A., Sobeck, A., Hendrickson, E. A., Moldovan, G. L., Shima, N., & Bielinsky, A. K. (2023). FANCD2-dependent mitotic DNA synthesis relies on PCNA K164 ubiquitination. Cell reports, 42(12), 113523. Advance online publication. [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, U. , & Eskazan, A. E. (2020). Moving on from 2013 to 2020 European LeukemiaNet recommendations for treating chronic myeloid leukemia: what has changed over the 7 years?. Expert review of hematology, 13(10), 1035–1038. [CrossRef]

- Valeri, A. , Alonso-Ferrero, M. E., Río, P., Pujol, M. R., Casado, J. A., Pérez, L., Jacome, A., Agirre, X., Calasanz, M. J., Hanenberg, H., Surrallés, J., Prosper, F., Albella, B., & Bueren, J. A. (2010). Bcr/Abl interferes with the Fanconi anemia/BRCA pathway: implications in the chromosomal instability of chronic myeloid leukemia cells. PloS one, 5(12), e15525. [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Patient Groups (%) n | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| CP-CML | AP-CML | P value | |

| (95.35) 123 | (4.65) 60 | ||

| Mean age (Range) | 33.5 (range 7-69) | 35.6 (range=27-43) | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | (60.2) 74 | (66.67) 40 | 0.60 |

| Female | (39.8) 49 | (33.33) 20 | 0.59 |

| Male: Female Ratio | 1.5:1 | 2:1 | 0.02 |

| Mean Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 10.1 | ||

| Mean WBC count (×109/L) | 313.7 | 315 | |

| 50> | (16.3) 20 | (20) 10 | 0.82 |

| 50=/< | (83.7) 103 | (80) 50 | 0.02 |

| P value | 0.005 | 0.02752 | |

| Platelets (× 109/L) Mean | 400.2 | ||

| <450 | 75 (61) | 40 (66.7) | |

| >/=450 | 33 (26.8) | 20 (33.3) | |

| No data found | 15 (12.2) | 0 | |

| P value | 0.0011 | 0.47 | |

| Imatinib | (66.7) 82 | (66.7) 40 | 0.72 |

| Interferon | (33.3) 41 | (0) 0 | 0.0038 |

| Chemotherapy | (8.1) 10 | (66.7) 40 | <0.0001 |

| Splenomegaly | |||

| cm 5> | (3.3) 4 | (0) 0 | 0.43 |

| cm 8–5 | (7.3) 9 | (16.7) 10 | 0.061 |

| cm 8< | (56.9) 70 | (83.3) 50 | 0.07 |

| No splenomegaly | (32.5)40 | (0) 0 | 0.004 |

| Hepatomegaly | |||

| Yes | (28.5) 35 | (66.7) 40 | 0.001 |

| Survival Status | |||

| Confirmed Deaths | 0 | (1.7) 1 | 0.0003 |

| Overall survival at last follow-up | (100) 123 | 59 (98.3) | 0.0003 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).