1. Introduction

Generation Z is a segment of the population born between 1997-2012, following millennials. They are regarded as the initial international group to be shaped in the twenty-first century, connected by digital applications, and active participation on social media. They become stereotyped as antisocial, tech-dependent, and social justice activists as a result of the latter. Hurrelmann & Albrecht (2021), however, claim that "Generation Z is a crucial, thought-provoking depiction of an astonishing generation that will deal with climate change and post-pandemic crisis. Dobrowolsk et al. (2022) emphasize that the world “can benefit from the qualities of generation Z—they gravitate towards gamified processes because of mobile-centricity; they are natives of global communication, self-learners, and self-motivators; they appreciate transparency”. The authors previously cited demonstrate how climate change affects people, and Greta Thunberg is credited with sparking political activism among people born after 2000. An essential pool of social capital is required for meaningful and lasting environmental participation and preservation in the individual and collective arenas, nevertheless, as generation Z transitions from school settings to societal decision-makers over the ensuing decades. The usual global issue of climate change calls for a concerted, group effort to address it (Smith & Mayer, 2018), and social capital plays a role. However, in addition to social capital, we must recognise the unique values that make Zed generation different from the others. According to conflicting research, they are less empathic than previous youth generations (Twenge, 2017). The body of literature charchterize Zed generation as, opne mind, creative, social inclusive, high tech-acceptable, innovative, participative on social media, more sharing and caring (Bassiouni & Hackley, 2014; Dougherty & Clarke, 2018; Schwieger & Ladwig, 2018; Campbell, P., 2018; Leopold & Bell, 2017; Mitchell, 2008; Pandit, 2015; Twenge, 2017). Still, as mentioned before, this generation is characterised by two opposing traits, anti-social and social justice warriors. The former inhibits the creation of social capital, while the latter enhances it. Putman (1993) emphasize that contemporary research on social capital position the collective actions at the centre of political and economic discours, and deriving from them tries to solve the issues coming from inside. Inspired by the theory of Putnam, several scholars show that social capital (SC) plays a substantial role in protecting the environment (Colin-Castillo & Woodward, 2015; Notaro & Paletto, 2011; Pretty & Ward, 2001; Su et al., 2021).

According to Putnam (2000), networks of civic involvement that establish generalized reciprocity norms and promote the emergence of social trust are another reason why life is easier in a community with a considerable stock of social capital. Civic participation is seen as the major source of trust, making it the foundational element of social capital according to Putnam. In addition, people who belong to associations are considerably more likely to engage in politics and show social trust than people who don't (Helliwell & Putnam, 1995; Putnam, 1993, 2000; Putnam, 2007). Between civic participation and interpersonal trust, Brehm & Rahn (1997) described an asymmetries. Increasing participation rates are more likely to occur in a community than cultivating a culture of increased trust among its members. As a result, building trust will be difficult without citizen engagement (Welter, 2012). However, a recent study in low- and middle-income countries shows that Putnam's linear view of civic engagement to trust is conditioned by institutional trust (Kokthi et al., 2021). Low trust in institutions is associated with low interpersonal trust, which is linked with low civic engagement.

Similarly, trust is the foundation root in unbaised, equitable, accountable and efficient institutions (Fairbrother, 2016; Rothstein, 2005; Rothstein & Stolle, 2008). Because of the salience effect, individuals extrapolate from the reliability of public leaders to estimate the reliability of the majority of the population. People are more prepared to give up material comforts in such cultures in order to protect communal resources like the environment.However, (Cropper & E.Oates, n.d.), following the neoclassical economics perspective, indicate that environmental amenities are considered "luxury goods" of concern for poor societies. Consequently, their positive or normative contribution to the environment will be low.

Inglehart (1995), however, found that both wealthy and poor countries were equally prepared to pay increased environmental protection fees. Poor civilizations frequently have more urgent environmental issues, which, according to Inglehart (1995), explains their favorable attitudes toward environmental conservation. Various age groups, though, have various levels of concern about the environment and climate change. According to Skeiryt et al. (2022) younger people in the EU are more likely to detect climate change than older people. In this context, the Zed generation is a thought-provoking segment to be analysed concerning climate change and environmental behaviour because they will enter the workforce soon and represent an important consumer segment. Also, generation Z is considered the first global generation. Technology, the globalisation of online entertainment, social trends, and communications are global as never before by reducing differences due to geographical placement. For that reason is expected that a Zed generation born in Albania will have the same traits as a zed generation somewhere else. At the same time, their influence in online communities makes them an essential component of influencers that can be activated for a higher impact of climate change policy response in a digitalised realm.

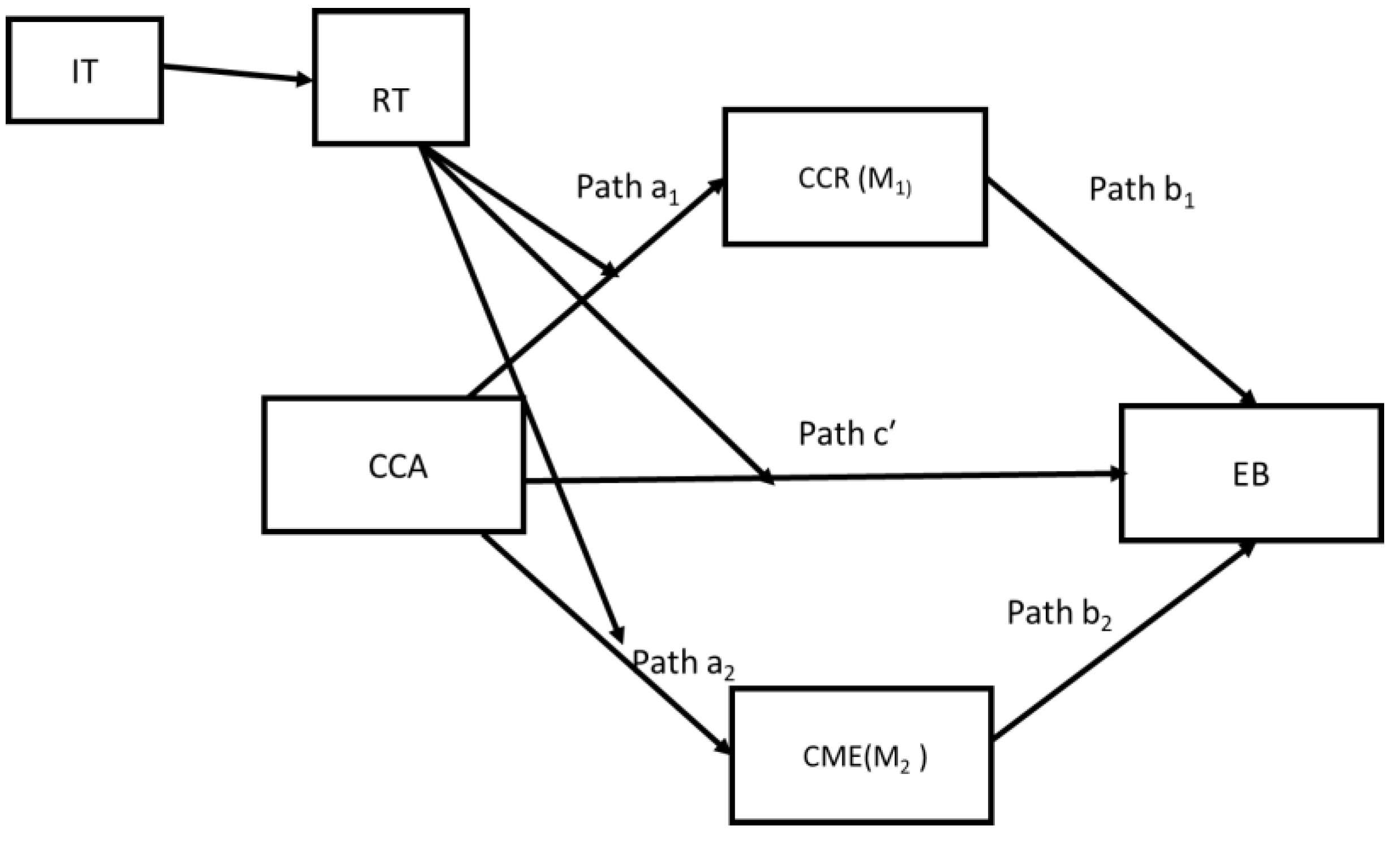

This empirical research tries to comprehend the conditional influence of social capital, particularly trust, on the environmental behavior of the Zed Generation. Two types of trust will be explored, institutional trust and radius of trust. First, the perspective of pathway analysis is chosen to investigate how environmental behavior is influenced by perceptions of climate change danger and involvement in environmental protection, and second, to comprehend how trust indicators can act as a moderator, as shown in

Figure 1. The conceptual model proposed in this paper, the input-output model, is an adaptation of the youth environmental engagement model (YEEP) (Watkins, 2019) and climate change risk perception (van Eck et al., 2020). The work flows as follow: initially it introduces the rationale of the zed generation and social capital interface in environmental behaviour and the study's objective. The methodological framework, research instrument and statistical approach are presented in the second section. In the third part, the findings are discussed, and in the fourth section, the conclusions are given.

2. Material and Method

2.1. Methodological Framework

2.1.1. Method and Conceptual Framework

Following input-output reasoning, four main components will be used to understand the Zed generation's behaviour toward the environment: (1) the initiating factor, (2) mediators, 3) moderators and (4) outcomes. The initiating factor is associated with the awareness of climate change (CCA). The most reliable indicator of both expressed intentions to engage in voluntary climate change mitigation efforts is understanding what drives climate change and what does not. ( Bord et al., 1998; Lee et al., 2015; Brechin & Bhandari, 2011). Similar to this, survey findings on global warming, whether on a national or international scale, are frequently summarized in terms of levels of awareness, actual knowledge, degree of worry, perceived risk, and willingness to pay for or make sacrifices in order to reduce or adapt to anticipated negative repercussions. (Bord et al., 1998). Nowadays is pretty documented the association between climate change awareness and the related perceived risks (Brechin & Bhandari, 2011). In the present research, we will test if this association is sustained in the Zedgeneration in Albania. The hypotheses to be tested in this case is:

H1: Higher awareness of climate change among the Zed generation is linked to increased risk perceptions for climate change (a1pathway)

The perception of climate change risk, on the other hand, is a strong predictor of minimizing its impacts (Farrokhi et al., 2020). Behavior intentions can also be explained by risk perceptions and a general belief that dangers from global warming pose a severe danger to society. (Bord et al., 2000). The Climate Change Risk Perception Model of van der Linden, (2015) comprises the following dimensions: 1)sociodemographics, 2)cognitive dimensions, 3)the experiential processing dimension, and 4)social norms and cultural orientation. Gender, age, education, income, and so on are important socio-demographic factors. The Zed generation cohort is used in the current study to reflect gender differences in income, education, work position, and age. The second level is cognition, which includes understanding of the factors that contribute to climate change as well as its effects and ways to combat them. 9.3% of the range in perceived risk of climate change may be accounted for by these factors. (van der Linden, 2015). According to these findings, CCA has been added (see

Table 1), with the assumption that "accurate" knowledge and awareness about climate change is a strong predictor of perceptions of climate change risk (Hornsey et al., 2016). In the suggested input-output model, CCA is framed as the initiator factor. The impact of extreme weather occurrences in one's life as well as individual experiences with them as well as the gravity of the challenges brought on by climate change are all part of the third dimension of experiential processing. In the present study, this dimension is measured with the perceived seriousness that climate change might result in the Zed generation's quality of life (CCR) (see

Table 1). Accordingly, to the proposed conceptual model, the CCR is considered a mediator in the pathway linking CCA with environmental behaviour EB. So, the hypotheses to be tested in this case are:

H2: Higher perceived risk of climate change is linked with a positive environmental behaviour (b2 pathway)

H3: Higher climate change awareness is linked with positive environmental behaviour (c` pathway)

Social norms and value orientations are included in the socio-cultural influences dimension, which is the final component/dimension. Van der Linden (2015) made a distinction between social norms that are descriptive and those that are prescriptive. The first refers to “the extent to which referent others are taking action to help reduce the risk of climate change”. In our study, we have considered the following statements that measure community engagement in different aspects and the environment. To be a good citizen means: 1)Always participating in voting, 2)Monitoring government activities, 3)Being active in community affairs, 4)Paying taxes regularly, 5)To help other citizens who are in worse condition than you, 6)and protecting the environment. The last one is used as the second mediator in the association CCA-EB, and the hypothesis to be tested is:

H4: Higher climate change awareness is linked with a increased community engagement (a2 pathway)

H5: A higher community engagement is linked with a positive environmental behaviour (b2 pathway)

Furthermore, Van der Linden's (2015) prescriptive social norms discuss the degree to which a person feels pressure from their social environment to perceive climate change as a risk that calls for action. Three statements are considered to analyse the Zed generation in Albania in that direction: 1) The government ought to lessen pollution, but I shouldn't have to pay for it.; 2)I think that protecting the environment is a less urgent issue than it is thought, and, 3) If we need to increase employment, we must also accept environmental problems.

As mentioned before, the applied quantitative empirical research examines the proposed conceptual (input-output) model and also includes two types of trust as the moderators of the pathway a

1b

1 (CCA-CCR-EB), a

2b

2 CCA-CME-EB, and pathway c` (CCA-EB). Numerous studies contend there is a substantial lack of public trust in the people, businesses, and institutions in charge of addressing climate change risk perceptions and environmental protection. (Buys et al., 2014; Inglehart, 1995; Malka et al., 2009; Notaro & Paletto, 2011; Slovic, 1993; van der Linden, 2015). The moderation perspective suggests that trust (IT&RT) inhibits or enhances the CCR, CME, and environmental behaviour (see

Figure 1). In this framework, we will test the following hypotheses:

H6: Trust will positively condition the pathway a1CCA-CCR

H7: Trust will positively condition the pathway a2 CCA-CME

Figure 1.

Conditional moderation of Institutional Trust in the relationship CCA-EB. Source: author's elaboration.

Figure 1.

Conditional moderation of Institutional Trust in the relationship CCA-EB. Source: author's elaboration.

2.1.2. Research Instrument

A closed structured questionnaire was chosen for this study. Three sections made up the latter's organization. Population data, including gender, age, education, income, and work status, are gathered in the first section (

Table 1). The second section aims to create a snapshot of the social capital indicators of the respondent by collecting information on institutional trust, civic engagement and cognitive, social capital. Considering that environmental behaviour is contingent on institutional quality and interpersonal trust, we have distinguished the two types of trust: institutional trust and the radius of trust of the individuals. For the purpose of avoiding the biases inherent with the question

"Generally, how much do you believe in others?," we utilize Fukuyama's radius of trust as a substitute for generalized trust. In familistic societies such as Albania, the answers to this question might be misleading to the accurate trust measurement. At the same time, civic engagement is assessed through the tangible civic engagement (EC) indicators following the Social Capital tool of the World Bank. Climate change awareness, risk perception, and environmental behavior are the main topics of the third section. Environmental behaviour is assessed with the willingness to contribute money to protect the environment.

Table 1 presents an explanation of the considered variables in this study.

Table 1.

Description of the variables included in the study.

Table 1.

Description of the variables included in the study.

1-Socio-demographic characteristics

2-Social capital indicators

3-Climate change and environmental behaviour |

-City (Tirana ) |

| -Age (in years). |

| -Gender (Male/Female). |

| -Educational level (Primary schooling/Secondary/High school/University). |

| -Income level in ALL (Albanian Currency) |

| Employment status (employed, unemployed, student) |

Social Capital indicators:

I. Institutional trust (IT) is analysed through the following statements : (1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree) :

1. Most politicians are in politics only for personal gain (related to Political trust) (IT1)

2. Most of the time, you believe the government is doing what is right. (IT2)

3. State institutions manage tax revenues effectively (IT3)

II. Civic engagement (CME) is examined by the following statements, measuring perceptions of community engagement

2.1.To be a good citizen, how important do you consider the following activities (where 1 = not at all important and 5 = very important)

1. Always participate in voting

2. Monitoring of government activities

3. Being active in community affairs

4. Pay taxes regularly

5. To help other citizens who are in worse condition than you

6. To protect the environment

2.2. Have you performed the following activity in the last three years? (yes and no answers). CE measures the actual civic engagement of zed generation participating in the study.

CE1 Voting during elections

CE2 Involvement in political, economic, and environmental organizations

CE3 Made an issue appealing to the media

CE4 Actively engaged in a public awareness campaign

CE5 Participated in a protest march or other protest activity

CE6 Donate money or goods to assist those who are struggling. CE7 Have you helped the community make a collective investment

CE8 Volunteer for a charitable organisation

CE9 Participate in government conceling processes

III. General Trust (GT) is measured using the radius of trust

Consider a situation where a resident of the village, town, or city and their family were forced to go. Whose care was it that they could leave "their house"?

1. No one

2. Neighbour

3. Anyone from the neighbours

4. Other family members

5. I do not know/not sure

6. Refused to reply; no answer |

III.1 Climate change general information (CCI)

1. Do you believe that the phenomenon of climate change has an impact on you? Is your life's quality impacted? Open question

III.2 Climate change awareness (CCA) (1=Not at all informed, 5=very much informed)

1. Are you aware of the danger of gas emission from vehicles that harms people's health?

2. Are you aware that using chemical fertilisers and pesticides will cause environmental damage?

3. Are you familiar with the risks posed by air pollution?

4. Are you aware of the risks associated with water pollution?

5. Are you aware of how dangerous a lack of green space may be?

6. Are you aware of the harm resulting from the deterioration of cultivated land quality?

Climate change and risk perceptions (CCRP)

1. If extreme weather occurs in your area, how serious is the impact on your life?

2. If a geological disaster occurs in your area, how serious is the impact on your life?

3. If vegetation destruction occurs in your area, how serious is the impact on people's lives?

4. If there is a water shortage in your area, how serious is the impact on your life? (1= not serious at all, 5=very serious) |

| 4-Environmental behaviour |

Environmental behaviour EB ( 1=strongly to disagree to 5=strongly agree)

1. I would agree to pay an environmental contribution if the money were to be used for the environment

2. I would agree to pay an environmental tax if the money were to be used for the environment

|

2.1.3. Sampling and Data Collection

260 respondents made up the sample used in the study as shown on demographics in

Table 2 below. Data were gathered in Albania, Tirana, between 10 December 2019 and 10 March 2022. The questionnaire was distributed online. The chosen outlet is in line with the target population of the study. The Zed generation spent most of their time on social media and online.

2.1.4. Data Analysis

Before analysing the results, a reliability test of the used construct was conducted. The results (

Table 3) show that the value of Cronbach's Alpha for the considered construct is above 0.785, which means that the reliability of the constructs is high and the use of the mediators is justified.

2.1.5. Statistical Approach

This study includes mediation and moderation analysis into its analytical process. (Hayes, 2018; Hayes & Rockwood, 2020; Igartua & Hayes, 2021). The path analysis perspective shows how climate change awareness CCA affects environmental behaviour (EB) through the mediation of change risk perceptions CCR and community engagement CME of Zed generation in Albania.

The moderated mediation model, which implies an input-output model (

Figure 1), implies there is a link between climate change awareness (CCA) and environmental behaviour (EB) is mediated in parallel by climate change risk perceptions (CCR) and perceptions of community engagement to protect the environment (CME). Furthermore, this mediation analysis is contingent on the stock of social capital (trust) of the participants in the study. Similarly, the effect of CCA in EB, its size and direction are moderated by the trust placed on institutions (IT) and the Radius of Trust (RT).

Institutional trust moderates (increase or decrease) the radius of trust, and the latter affects the following pathways a1- CCA-CCR, a2-CCA-CME and c`-CCA-EB. The validity of using IT and RT is also demonstrated in other similar research undertaken in Albania (Kokthi, Guri, et al., 2021; Kokthi, Muço, et al., 2021). In the same vien the work of Barnett et al.(2019) relate the trust to isnitutions with the approach towards politics and highlights the conservative people about politics show at the same time a decresed level of attitude toward environmental issues. The positive point in here is that such attitude in addition is linked with a higher generativity which implies a positive indirect effect on the environmental issues.

We will investigate whether interactions between two types of social capital, IT and RT, facilitate, enhance, or inhibit the effect of awareness on climate change risk perception, community engagement toward the environment, and environmental behavior in the Zed Generation through the input-output conceptual model suggested in

Figure 1. To evaluate the moderated-moderated mediation impact of social capital in the link between CCA and EB, the "PROCESS" macro, model 11 (Hayes, 2013), in SPSS, with bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals, and bootstrapping, was utilized (

Figure 1).

3. Discussion of Results

Environmental aspects related to raising awareness, climate change perceptions and community engagement toward climate change can be achieved only by the cooperation of communities on a larger scale. Similarly, the cooperation of communities on big scales (such as cities, regions, and countries) is conditioned by the level of cooperation on more minor scales, and the latter is contingent on the level of trust. In the present study, we used a scenario type of question to understand the radius of trust of the respondents: Consider a situation where a resident of the village, town, or city and their family were forced to go. Whose care was it that they could leave "their house"? A restricted circle of trust would allow 67% of respondents to leave their home with their parents or other immediate family members, 15% with their closest neighbor, and the remaining 40% would not leave at all. These results align with a similar study in Albania in a rural community where 55% of the participants also show a narrow trust radius but wider than the radius of trust in the present study. The result is probably linked to the study's location and age. Tirana, the capital of Albania, comprises a diverse population from all other areas of Albania. Despite the fact that the level of trust is somehow low, the promising aspect in here is that as Barnett et al.(2019) show, people with low level of trust show at the same time great level of concern about the future. Putnam shows that in the short term, the diversity of the population inhibits social cohesion and, as a result, the stock of social capital (R. D. Putnam, 2007). However, other studies contradict Putnam's results by saying that it is not the diversity that causes the low social capital but the low individual trust inherent in the considered population (Baldassarri & Abascal, 2020). In Albania, the radius of trust is conditioned by the tendency of groups to create family ties, which in themselves represent closed networks that create ties of reciprocity only within the family circle. People have lower amounts of social capital in civilizations where trust is restricted to the nuclear family or kinship alone. According to Realo et al. (2008), social capital grows as the trust circle expands.

Similar to this, community mistrust coexists with a lack of confidence in government agencies (Kokthi et al., 2021). The study's findings overwhelmingly demonstrate a lack of faith in institutions, and the Zed generation thinks that most politicians merely want public office for their own benefit. They do not believe that the government is doing what is right and that the tax revenues are not managed effectively. See

Table 4 for results.

In order to better understand the Zed generation's environmental behavior, the paper also looks at structural social capital among them. According to a study on civic engagement of the participants as that shown on

Table 5, 31% of respondents were involved in political, economic, and environmental associations, 30% had taken part in demonstrations in public, and 30% had actively participated in electoral campaigns. While 30% of respondents actively participated in an information campaign, just 9% of respondents got the media's attention on a topic. Additionally, almost 64% of responders work as volunteers for a charity. Sixty percent of respondents said they have donated in-kind goods in the previous five years when asked about the topic.

Several key elements carried over from the authoritarian past, which hinder the growth of civil society in post-communist Albania, include the predominance of the Communist Ideology, forced structured voluntarism, mandatory membership in state-controlled socio-political organizations, and mistrust of local community members (Bino et al., 2020; Kokthi et al., 2021). However, the young generation seems to escape from this general trend; the percentage of voters in the last elections reinforces this trend (65%). In conclusion, the respondents participating in the study show a low radius of trust and institutional trust, but at the same time, they show a higher structural social capital than their rural counterparts.

Beyond the snapshot of the social capital manifestation in Zedgeneration in Albania, we have explored if it has affected awareness of climate change (CCA), climate change risk perceptions (CCR), community engagement toward the environment (CME) and environmental behaviour (EB). EB is considered the outcome of this input-output framework.

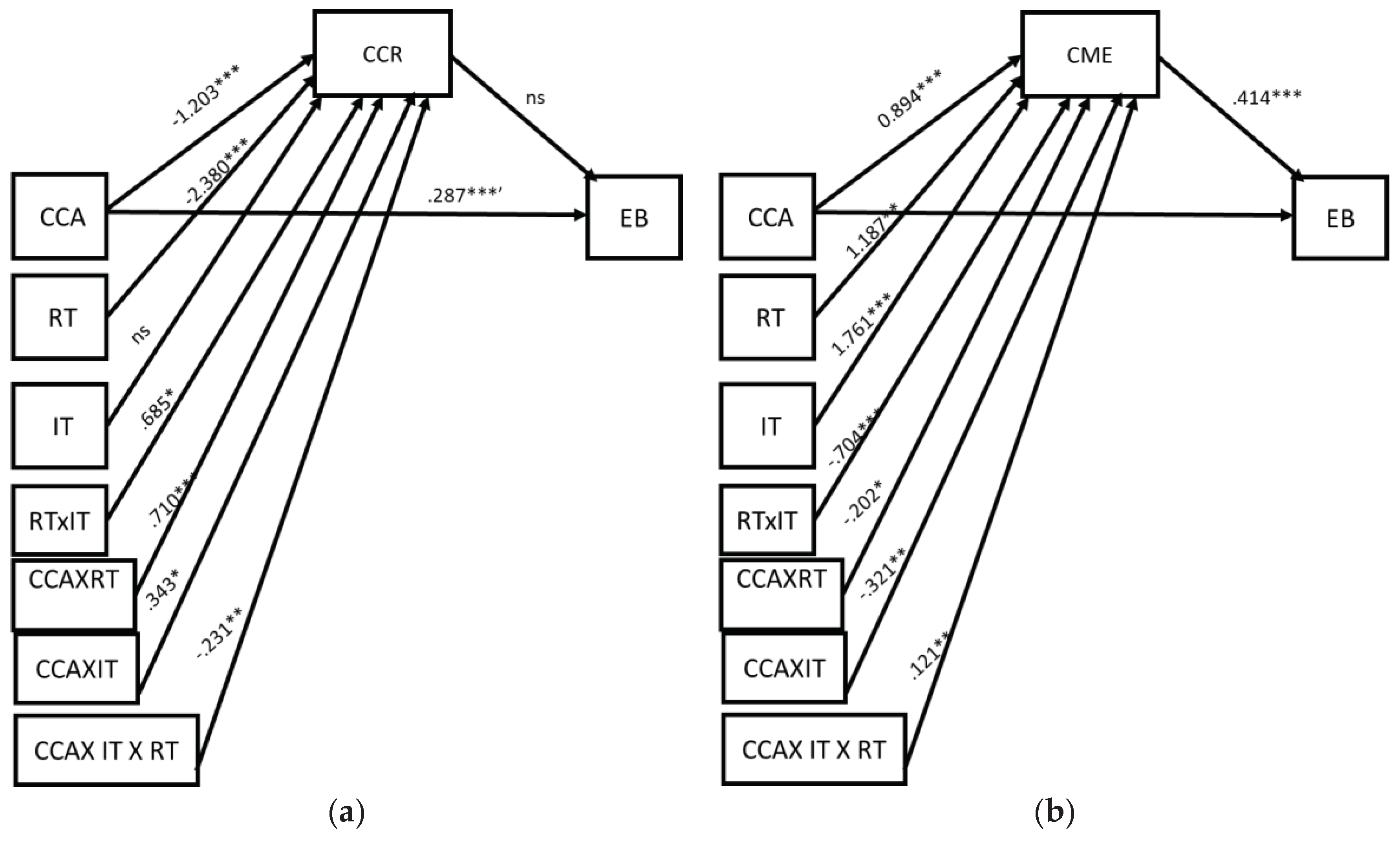

Figure 2 shows the pathway analysis results applied in the conceptual model suggested in

Figure 1. The results of pathway one CCR= iM+ a

1CCA+βIT (1) indicate a significant variation in climate change risk perceptions, R2=.088; F(3,456), p=.002. Climate change awareness and radius of trust have the highest effect on CCR with a negative sign. Indicating that participants with higher awareness show lower climate change risk perceptions. This outcome might be linked to their low confidence in their knowledge or because they are sceptic about climate change risks as other individuals do worldwide (Haltinner & Sarathchandra, 2021; Urry, 2015). In the same vein, respondents with a higher radius of trust perceive less climate change risk. Studies show that general trust is associated with lower fear levels and leads to socially desirable behaviours (Jovančević & Milićević, 2020) and general trust and general confidence negatively influence risk perception (Siegrist et al., 2005).

Similarly, according to Smith & Mayer (2018), risk and trust are important predictors of climate change behaviour. However, in the present research, institutional trust separately does not significantly affect the CCR, while in interaction with the radius of trust, they positively affect risk perceptions (b=.685, pvalues=.000) see

Figure 1 (A). Individual trust alone is insufficient to produce climate change risk perceptions among the zed generation; institutional trust is also needed. Moreover, the interaction of CCA with the two types of trust, individual and institutional, shows a positive effect (see

Figure 1 A). The effect of individual trust (b=.710) and CCA interaction is higher than institutional trust (b=343), which means that high-trust individuals aware of climate change issues will show a higher risk perception than the participants who express high institutional trust. This pattern is also comforted by the interaction CCAxRTxIT, showing a negative sign, implying that both types of trust are needed to show a climate change risk perception. Lower trust in institutions will reduce the perceived risk, and the effect of individual trust in climate change risk perceptions is crucial in mitigating climate change (Farrokhi et al., 2020). .

In the second pathway, climate change awareness significantly affects CME (b=0.894;pvalue=.000). High awareness is related to higher engagement in Zed Generation. Also, institutional (effect=1.761, p(value)=.000) and radius of trust (b=1.187;pvalue=0.017) show a significant positive effect. The effect of IT is greater than the effect of RT. These results are in line with other research undertaken in rural Albania. Higher institutional trust is associated with higher individual trust and civic engagement (Kokthi, Guri et al., 2021).

Similarly, individual and institutional trust significantly predicts CME. The findings show a negative moderating effect of the interaction RTx IT (see

Figure 1 (B)). Comforting the previous findings, environmental engagement in youth is conditional on trust levels. The higher the trust, the higher the engagement. Also, the separate interaction between CCAxRT, (effect b=-.202,pvalue=.094), and CCAxIT (b=-.321;pvalue=.004 ) show a negative effect. While the interaction between CCAxRTxIT b=.122;pvalue=.025 show a positive effect on CME. The negative coefficient shows that low trust in institutions and a low radius of trust are associated with low CME. The negative effect is higher when the two types of social capital interact (ITxRT, b=-.704. pvalue=.002). However, when the two types of social capital interact with CCA, they significantly positively affect CME. Thus, to have a positive effect of CCA in CME, we need both types of trust, institutional and individual. Climate change perceptions of the citizens depend on how they evaluate the government. If the government highlights the climate change risks and the individuals trust the government, the population will show the same tendency, but when trust is lacking, the contrary is true.

Trust indicators did not show a significant effect in the pathway c`, which indicates the direct association between climate change awareness and environmental behaviour (EB= iM+ a1CCA+βIT+e)

The results show that both CCA (b=.298;pvalue=.000) and CME (b=.431;pvalue=.000) effect EB, while the CCR is not affecting it. Contrary to what is shown in the literature, citizens behave positively toward environmental protection in developing countries when they perceive that the deterioration is affecting their daily lives. With the Zed generation, this is not the case. If Zedgen is better informed on environmental issues, they will engage more, and consequently, they will pay to protect the environment. However, even in this generation, the low trust in institutions reduces the perceived risks of climate change. The index of moderated-moderated mediation (IMMM) of pathway a1 also comforts these results, IMMM=-.007, BootLLCI -.034;BootULCI .012. While the IMMM of the second pathway is IMMMa2=. 053, higher institutional trust condition the effect of CCA in community engagement (CE1) which affects environmental behaviour. Through Hayes Model 11, we have shown that CCA significantly affects pathway a2, meaning that climate change awareness affects more community environmental engagement than risk perceptions (CCR). Levels of trust also condition this association. Individuals with low levels of trust will perceive less risk because they are not confident in the sources that give information on the impacts of climate change.

Consequently, we clearly understand pathways affected by social capital (IT, RT) from a moderation-moderation perspective. Trust is an important indicator of engagement in the Zed generation. They will engage more if they trust more.

As shown on the

Table 6, the first hypothesis is rejected which in fact can be interpreted as normal, because if we analyse the current situation the fact that the generation do not persive climate risk is due to low information and awareness towards it. In this regard, Derber and Nowak (2008) perceiving the risk of climate change is among the largest collective action issues noewdays. Moreover, one of the most important issue in climate change awareness is the notion that the audience should be "segmented" into various groups based on variations in their views or beliefs, for which Corner et al. (2014) uses the term “values-based communication of climate change” in different awareness raising campaings for public engagement. The hypothesis 2 as well is rejected, derived from lower risk perceived logically does not foster further behavior change bacuse, human values (in this case bahviour change for climate issues) are believed to be relatively stable aspects of people's personalities and conduct as opposed to fleeting preferences, in contrast to the economic dimension (although they may change over the course of an individual's lifetime) (Thompson, 1981; Inglehart, 2008). It is specified above that this study is conducted in sample coming from a very harsh communism regime which strictely borbided reactive behaviours.

Hypothesis 3, 4 and 5 are accepted showing that, higher climate change awareness is associated with positive environmental behaviour (c` pathway) and higher climate change awareness is associated with a higher community engagement (a2 pathway) which further impies higher positive behaviour. This result is inline with the literature starting Nilson et al. (2004) which firstly examine the predicting acceptance of participative behavior with the beliefs and values about the climate change. This is also supported by other works (Corner et al., 2011; Poortinga et al., 2011; Whitmarsh, 2011) which highlight that particpative and willing to accept group of pesons are more likely to concern about the risk and consequences of climate change and the gravity of this issue. Climate change engagement among differnet age and social groups throught the years has been studied by different scholars ( Marquart-Pyatt et al., 2011; McCright et al., 2011) and the common result of them is that participative persons have higher perception of climate change risk. Hence, developing countries are more collective societies (Brechin and Lever-Tracy, 2010) and the individual responsibility towards issues like climate change may be less dominant (Hamedani et al., 2013). Hypotheis 6 is lightly linked with hypothesis 1 and logicaly it is rejcated since the fisrt one also was rejected. To understand this “inaction” a term used by Hornsey and Fielding (2020) we use their argument that climate change mitigation is decelerated by the high climate skepticism and the failure to properly transmit the meaningful actions initiated on this concern. As the other body of literature this work also related the inaction with the roles of demographies, ideologies and confronting conspirative ideas which shape human believes and willingness. This study considers Zed generation and as Klineberg et al. (1998) showed age and education is among demographics that strongly measures the environmental concern. The time horizons for such actions to take place are long term, which sometimes is difficult to deeply be undertood by generations and group age.s. Moreover, societies must be motivated to be engaged and to be associated with environmental issues for this reason Zaval et al. (2015) suggest “the positive legacy” to be attached in conserving the environment.

Hypothesis 7 is sustained as overall but when analysed specificly institutiona trust and radius of trust do not reflect to positively influence which means that Zed generation has a higher trust among their core values but not apprant toward what. A strong argument in this regard is that in general younger persons have a lower perceived obligation for future generations and due to that neglect environmental attitudes (Watkins & Goodwin, 2019).

Such result are refert to in literature as “power assymetry” which cause a disbalanced resource allocation among different geenrations (Tost et al.,2008; Handgraaf et al.,2008). Jacquet et al. (2013) evidenced that short term thinking is prevalent in different group ages. To increase the motivation for social responcive actions, generations must consider reciprocity and think about the sactifices past generations have done for the sake of our benefits (Bang et al., 2017; Wade-Benzoni, 2019), bacuse the idea that you will be rembeered for something good is among the most powerful feelings.

4. Conclusions

The Zed generation is a thought-provoking segment to be analysed concerning climate change and environmental behaviour because they will enter the workforce soon and represent an important consumer segment and also because generation Z is considered the first global generation. This study tried to understand the conditional effect of social capital, mainly trust, on the Zed Generation's environmental behaviour. Two types of trust were explored, institutional trust and radius of trust. The perspective of pathway analysis was selected first to examine the role of climate change awareness in environmental behaviour through the mediation of climate change risk perceptions and engagement to protect the environment and second, to understand the moderating effect of trust indicators

Based on the results, environmental aspects related to raising awareness, climate change perceptions and community engagement toward climate change can be achieved only by the cooperation of communities on a larger scale. But, the cooperation of communities on big scales (such as cities, regions, and countries) is conditioned by the level of cooperation on more minor scales, and the latter is contingent on the level of trust. However, the young generation seems to escape from this general trend somehow.

In conclusion, the respondents participating in the study show a low radius of trust and institutional trust, but at the same time, they show a higher structural social capital than their rural counterparts. Trust indicators did not show a significant effect in the pathway which indicates the direct association between climate change awareness and environmental behavior. If Zedgen is better informed on environmental issues, they will engage more, and consequently, they will pay to protect the environment. However, even in this generation, the low trust in institutions reduces the perceived risks of climate change.

The main conclusions are that, higher climate change awareness is associated with a higher community engagement; higher community engagement is associated with a positive environmental behavior and; trust (both institutional and radius of trust) will positively condition the pathway.

The application of the input-output model shows that the pathway that directly affects environmental behaviour among Zed Generation in Albania is not Climate change risk perception. In low-trust contexts, positive environmental behaviour can be generated through community engagement. Policymakers and educational programmes in low-middle-income countries might consider community engagement to mitigate trust issues and effectively deal with environmental problems with a global segment such as the Zed generation.

Based on the obve concluding remarks, we consider that the “time-horizon” is a very crucial element in the behaviour toward climate change. Some times it is difficulty for people to perceive the level and mangintue of the impact something may have in the near or far future on (Hornsey & Fielding, 2019; Jacquet et al. 2013). Due to that we would suggest considering intergenerational discounting which as Syropoulos & Markowitz (2021) clarify is “discounting of future benefits and harms that acrue to future others”. Finaly, to diminish it, as Hurlstone et al., (2020) suggest we should increase the intergenerational reciprocity and motivate a positive legacy to have a better climate change action and trust of Zed generation. Intisutionals have the responsibility to increase the trust among the public, especially among youngers. Zed generation have a long lasting way ahead and if there is a tust in between there must happen the moderated delegation of “generation’s future” as e legacy in a “bonna fide”.

Ethical Approval

This work maintain high standards of personal conduct, practicing honesty in all our professional relationships and endeavors. We have been truthful in our actions, data, reports, analysis and statement done for the sake of this work.

Consent to Participate

All the authors understand the general purposes, risks and methods of this research. We consent to participate in the research project.

Concent to Publish

We hereby provide consent for the publication of the manuscript detailed above, including accompanying images or data contained within the manuscript. We confirm that we have been given the opportunity to view the manuscript prior to publication, and we understand that once published, it cannot be removed from the published record except in exceptional circumstances.

Funding

“The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.”.

Competing Interests

“The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.”.

References

- Baldassarri, D., & Abascal, M. (2020). Diversity and prosocial behavior. Science, 369(6508), 1183–1187. [CrossRef]

- Bang, H. M., Koval, C. Z., & Wade-Benzoni, K. A. (2017). It's the thought that counts over time: The interplay of intent, outcome, stewardship, and legacy motivations in intergenerational reciprocity. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 73, 197-210.

- Barnett, M. D., Archuleta, W. P., & Cantu, C. (2019). Politics, concern for future generations, and the environment: Generativity mediates political conservatism and environmental attitudes. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 49(10), 647–654. [CrossRef]

- Bino, B., Redion Qirjazi, & Alban Dafa. (2020). Pjesëmarrja e Shoqërisë Civile në Vendimmarrje në Shqipëri (p. 58). Westminster Foundation for Democracy.

- Bord, R. J., O’Connor, R. E., & Fisher, A. (2000). In what sense does the public need to understand global climate change? Public Understanding of Science, 9(3), 205–218. [CrossRef]

- Brechin, S. R., & Bhandari, M. (2011). Perceptions of climate change worldwide. WIREs Climate Change, 2(6), 871–885. [CrossRef]

- Brechin, S. R., & Lever-Tracy, C. (2010). Routledge Handbook of Climate Change and Society.

- Brehm, J., & Rahn, W. (1997). Individual-Level Evidence for the Causes and Consequences of Social Capital*. American Journal of Political Science, 41(3), 999.

- Buys, L., Aird, R., van Megen, K., Miller, E., & Sommerfeld, J. (2014). Perceptions of climate change and trust in information providers in rural Australia. Public Understanding of Science, 23(2), 170–188. [CrossRef]

- Colin-Castillo, S., & Woodward, R. T. (2015). Measuring the potential for self-governance: An approach for the management of the common-pool resources. International Journal of the Commons, 9(1), 281. [CrossRef]

- Corner, A., Markowitz, E., & Pidgeon, N. (2014). Public engagement with climate change: the role of human values. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 5(3), 411-422. [CrossRef]

- Corner, A., Venables, D., Spence, A., Poortinga, W., Demski, C., & Pidgeon, N. (2011). Nuclear power, climate change and energy security: Exploring British public attitudes. Energy Policy, 39(9), 4823-4833. [CrossRef]

- Cropper, M. L., & E.Oates, W. (n.d.). Environmental Economics: A Survey. Journal of Economic Literature, 30(2), 675–740.

- Dobrowolski, Z., Drozdowski, G., & Panait, M. (2022). Understanding the impact of Generation Z on risk management—A preliminary views on values, competencies, and ethics of the Generation Z in public administration. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(7), 3868. [CrossRef]

- Fairbrother, M. (2016). Trus tand Public Support for Environmental Protectionin Diverse National Contexts. 3, 359–382.

- Farrokhi, M., Khankeh, H., Amanat, N., Kamali, M., & Fathi, M. (2020). Psychological aspects of climate change risk perception: A content analysis in Iranian context. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 9(1), 346. [CrossRef]

- Haltinner, K., & Sarathchandra, D. (2021). The Nature and Nuance of Climate Change Skepticism in the United States*. Rural Sociology, 86(4), 673–702. [CrossRef]

- Hamedani, M. G., Markus, H. R., & Fu, A. S. (2013). In the land of the free, interdependent action undermines motivation. Psychological Science, 24(2), 189-196.

- Handgraaf, M. J., Van Dijk, E., Vermunt, R. C., Wilke, H. A., & De Dreu, C. K. (2008). Less power or powerless? Egocentric empathy gaps and the irony of having little versus no power in social decision making. Journal of personality and social psychology, 95(5), 1136. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Communication Monographs, 85(1), 4–40. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F., & Rockwood, N. J. (2020). Conditional Process Analysis: Concepts, Computation, and Advances in the Modeling of the Contingencies of Mechanisms. American Behavioral Scientist, 64(1), 19–54. [CrossRef]

- Helliwell, J. F., & Putnam, R. D. (1995). Economic Growth and Social Capital in Itali. Eastern Economic Journal, 3, 295–307.

- Hornsey, M. J., & Fielding, K. S. (2020). Understanding (and reducing) inaction on climate change. Social Issues and Policy Review, 14(1), 3-35.

- Hornsey, M. J., Harris, E. A., Bain, P. G., & Fielding, K. S. (2016). Meta-analyses of the determinants and outcomes of belief in climate change. Nature Climate Change, 6(6), 622–626. [CrossRef]

- Hurlstone, M. J., Price, A., Wang, S., Leviston, Z., & Walker, I. (2020). Activating the legacy motive mitigates intergenerational discounting in the climate game. Global Environmental Change, 60, 102008. [CrossRef]

- Hurrelmann, K., & Albrecht, E. (2021). Gen Z: Between climate crisis and coronavirus pandemic. Routledge.

- Igartua, J.-J., & Hayes, A. F. (2021). Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: Concepts, Computations, and Some Common Confusions. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 24, e49. [CrossRef]

- Inglehart, R. (1995). Public Support for Environmental Protection: Objective Problems and Subjective Values in 43 Societies. 28(1), 57–72.

- Inglehart, R. (2008). Changing Values among Western Publics from 1970 to 2006. West European Politics, 31.

- Jacquet, J., Hagel, K., Hauert, C., Marotzke, J., Röhl, T., & Milinski, M. (2013). Intra-and intergenerational discounting in the climate game. Nature climate change, 3(12), 1025-1028.

- Jovančević, A., & Milićević, N. (2020). Optimism-pessimism, conspiracy theories and general trust as factors contributing to COVID-19 related behavior – A cross-cultural study. Personality and Individual Differences, 167, 110216. [CrossRef]

- Klineberg, S. L., McKeever, M., & Rothenbach, B. (1998). Demographic predictors of environmental concern: It does make a difference how it's measured. Social science quarterly, 734-753.

- Kokthi, E., Guri, G., & Muco, E. (2021). Assessing the applicability of geographical indications from the social capital analysis perspective: Evidences from Albania. Economics & Sociology, 14(3), 32–53. [CrossRef]

- Kokthi, E., Muço, E., Requier-Desjardins, M., & Guri, F. (2021). Social capital as a determinant for raising ecosystem services awareness—An application to an Albanian pastoral ecosystem. Landscape Online, 95, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Lee, T. M., Markowitz, E. M., Howe, P. D., Ko, C.-Y., & Leiserowitz, A. A. (2015). Predictors of public climate change awareness and risk perception around the world. Nature Climate Change, 5(11), 1014–1020. [CrossRef]

- Malka, A., Krosnick, J. A., & Langer, G. (2009). The Association of Knowledge with Concern About Global Warming: Trusted Information Sources Shape Public Thinking. Risk Analysis, 29(5), 633–647. [CrossRef]

- Marquart-Pyatt, S. T., Shwom, R. L., Dietz, T., Dunlap, R. E., Kaplowitz, S. A., McCright, A. M., & Zahran, S. (2011). Understanding public opinion on climate change: a call for research. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, 53(4), 38-42.

- McCright, A. M., & Dunlap, R. E. (2011). The politicization of climate change and polarization in the American public's views of global warming, 2001–2010. The Sociological Quarterly, 52(2), 155-194.

- Nilsson, A., von Borgstede, C., & Biel, A. (2004). Willingness to accept climate change strategies: The effect of values and norms. Journal of environmental psychology, 24(3), 267-277.

- Notaro, S., & Paletto, A. (2011). Links between Mountain Communities and Environmental Services in the Italian Alps. 51(2).

- Poortinga, W., Spence, A., Whitmarsh, L., Capstick, S., & Pidgeon, N. F. (2011). Uncertain climate: An investigation into public scepticism about anthropogenic climate change. Global environmental change, 21(3), 1015-1024. [CrossRef]

- Pretty, J., & Ward, H. (2001). Social Capital and the Environment. World Development, 29(2), 209–227. [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R. (1993). The Prosperous Community Social Capital and Public Life. The American Prospect, 13(4).

- Putnam, R. (2000). Bowling Alone: America’s Declining Social Capital. Culture and Politics, 223–234.

- Putnam, R. D. (2007). E Pluribus Unum: Diversity and Community in the Twenty-first Century The 2006 Johan Skytte Prize Lecture. Scandinavian Political Studies, 30(2), 137–174. [CrossRef]

- Realo, A., Allik, J., & Greenfield, B. (2008). Radius of Trust: Social Capital in Relation to Familism and Institutional Collectivism. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 39(4), 447–462. [CrossRef]

- Richard J. Bord, Ann Fisher, & Robert E. O\’Connor. (1998). Public perceptions of global warming: United States and international perspectives. Climate Research, 11(1), 75–84. [CrossRef]

- Rothstein, B. (2005). Social Traps and the Problem of Trust (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press. [CrossRef]

- Rothstein, B., & Stolle, D. (2008). The State and Social Capital An Institutional Theory of Generalized Trust. 40(4), 441–459. [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, M., Gutscher, H., & Earle, T. C. (2005). Perception of risk: The influence of general trust, and general confidence. Journal of Risk Research, 8(2), 145–156. [CrossRef]

- Skeirytė, A., Krikštolaitis, R., & Liobikienė, G. (2022). The differences of climate change perception, responsibility and climate-friendly behavior among generations and the main determinants of youth’s climate-friendly actions in the EU. Journal of Environmental Management, 323, 116277. [CrossRef]

- Slovic, P. (1993). Perceived Risk, Trust, and Democracy. Risk Analysis, 13(6), 675–682. [CrossRef]

- Smith, E. K., & Mayer, A. (2018). A social trap for the climate? Collective action, trust and climate change risk perception in 35 countries. Global Environmental Change, 49, 140–153. [CrossRef]

- Su, F., Song, N., Shang, H., Wang, J., & Xue, B. (2021). Effects of social capital, risk perception and awareness on environmental protection behavior. Ecosystem Health and Sustainability, 7(1), 1942996. [CrossRef]

- Syropoulos, S., & Markowitz, E. M. (2021). Perceived responsibility towards future generations and environmental concern: Convergent evidence across multiple outcomes in a large, nationally representative sample. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 76, 101651. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, K. S. (1981). Changes in the values and life-style preferences of university students. The Journal of Higher Education, 52(5), 506-518.

- Tost, L. P., Hernandez, M., & Wade-Benzoni, K. A. (2008). Pushing the boundaries: A review and extension of the psychological dynamics of intergenerational conflict in organizational contexts. Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management, 27, 93-147.

- Urry, J. (2015). Climate Change and Society. In J. Michie & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Why the Social Sciences Matter (pp. 45–59). Palgrave Macmillan UK. [CrossRef]

- van der Linden, S. (2015). The social-psychological determinants of climate change risk perceptions: Towards a comprehensive model. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 41, 112–124. [CrossRef]

- van Eck, C. W., Mulder, B. C., & van der Linden, S. (2020). Climate Change Risk Perceptions of Audiences in the Climate Change Blogosphere. Sustainability, 12(19), 7990. [CrossRef]

- Wade-Benzoni, K. A. (2019). Legacy motivations & the psychology of intergenerational decisions. Current opinion in psychology, 26, 19-22. [CrossRef]

- Watkins, H. M., & Goodwin, G. P. (2020). Reflecting on sacrifices made by past generations increases a sense of obligation towards future generations. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 46(7), 995-1012. [CrossRef]

- Whitmarsh, L. (2011). Scepticism and uncertainty about climate change: Dimensions, determinants and change over time. Global environmental change, 21(2), 690-700. [CrossRef]

- Zaval, L., Markowitz, E. M., & Weber, E. U. (2015). How will I be remembered? Conserving the environment for the sake of one’s legacy. Psychological science, 26(2), 231-236. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).