Submitted:

22 December 2023

Posted:

25 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Epidemiology

Maternal Infection

Contamination

Symptomatology

Screening

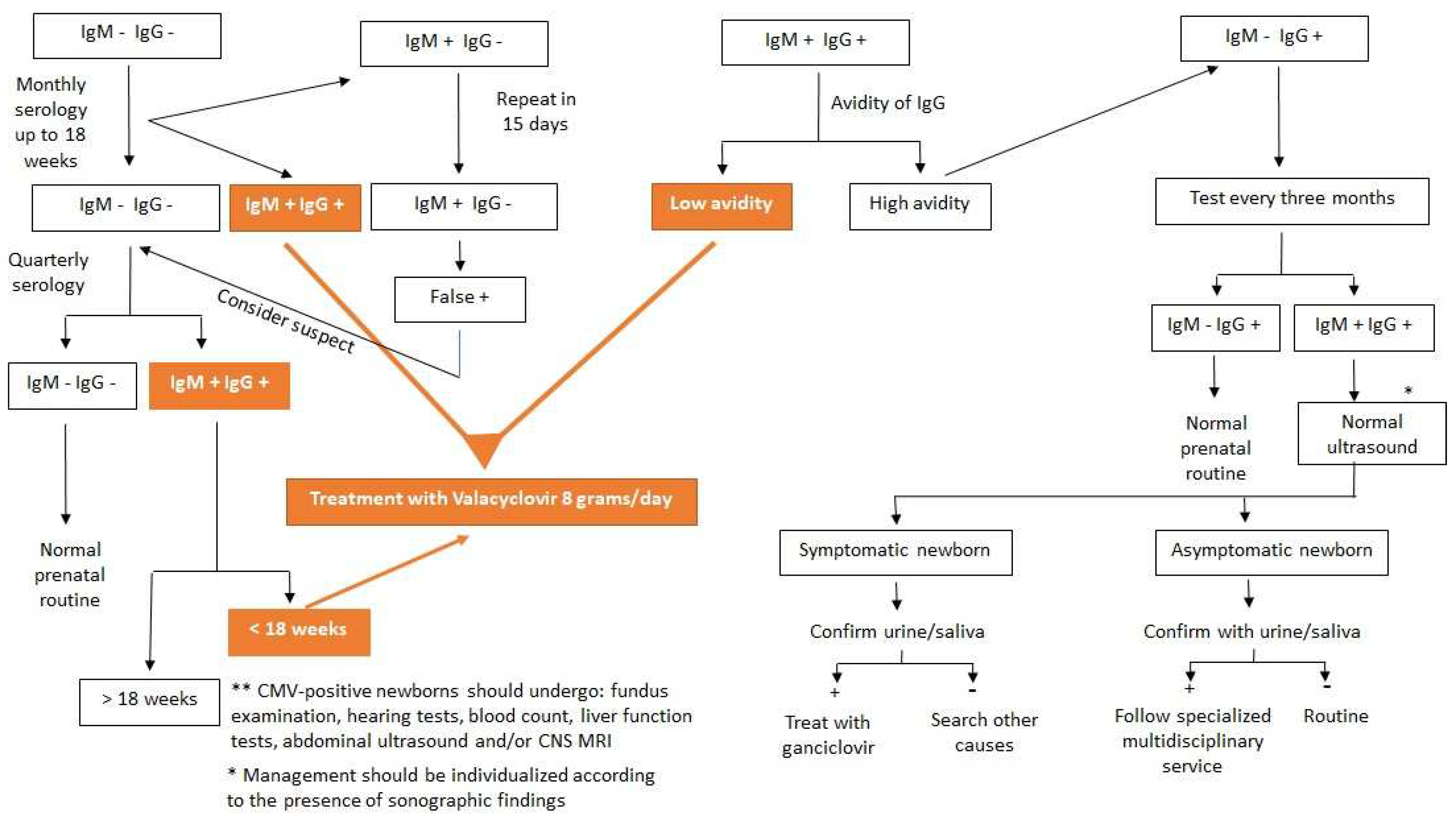

Serologies and Interpretations

Congenital Infection

Transmission

Pathophysiology

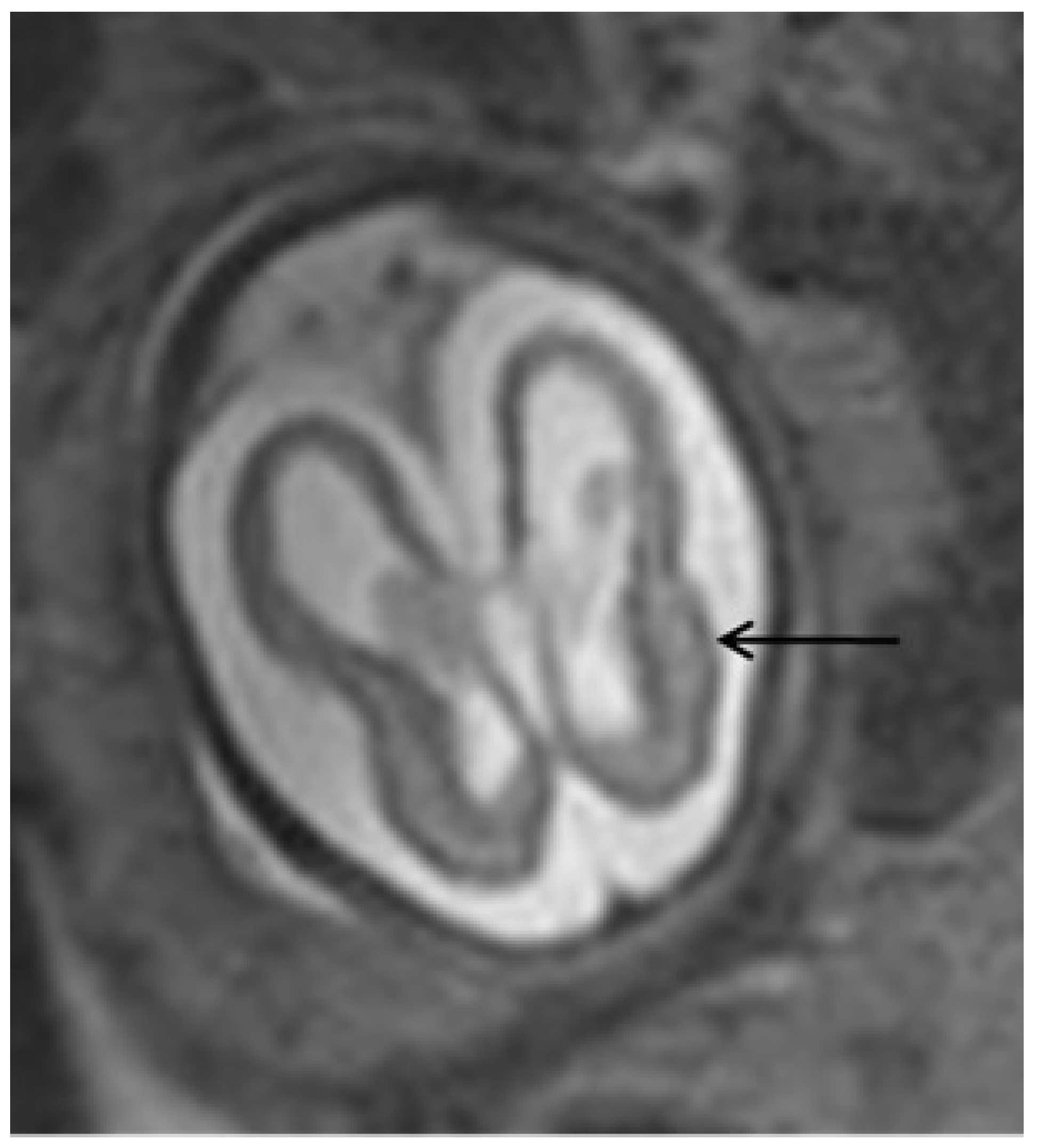

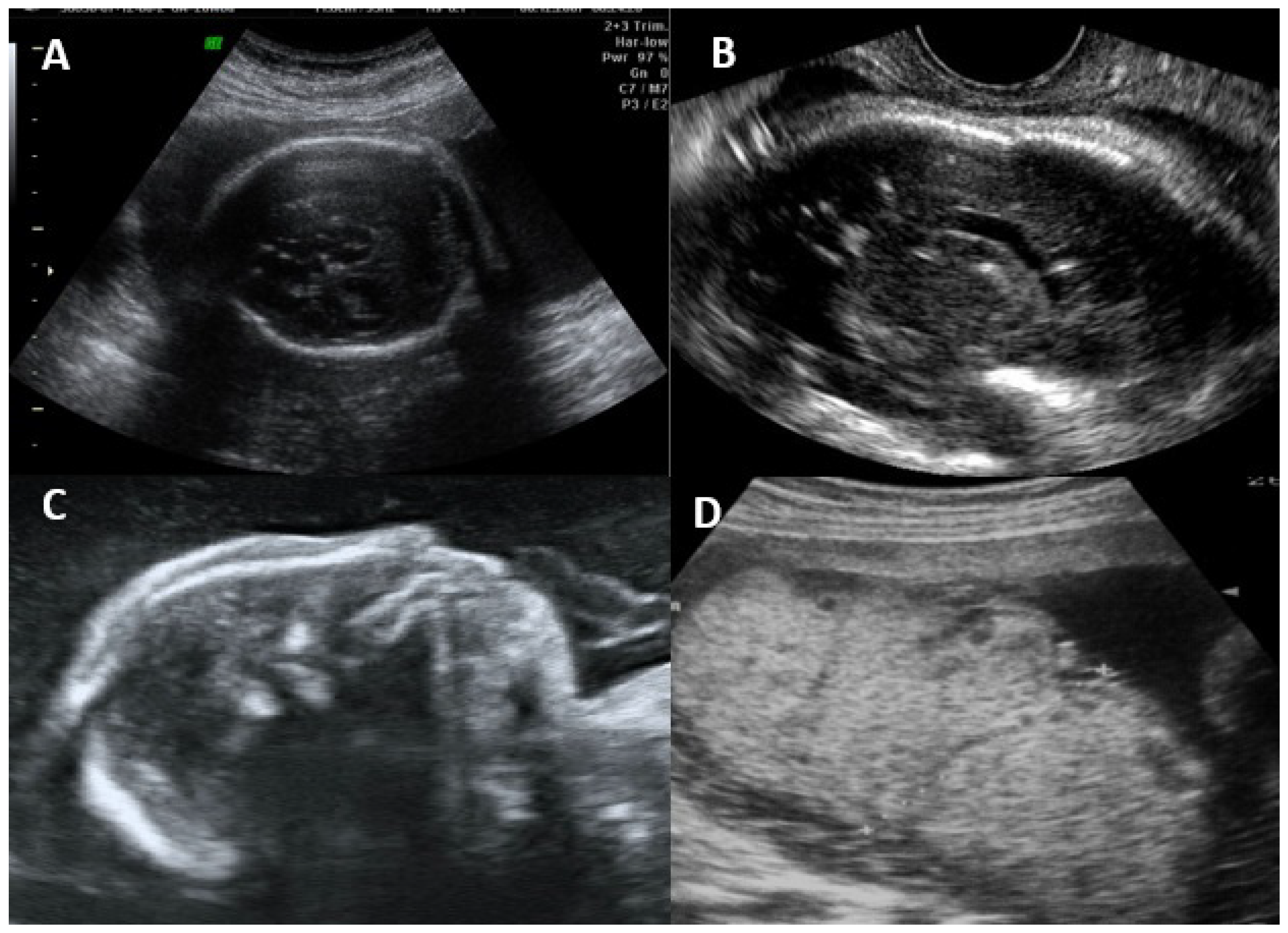

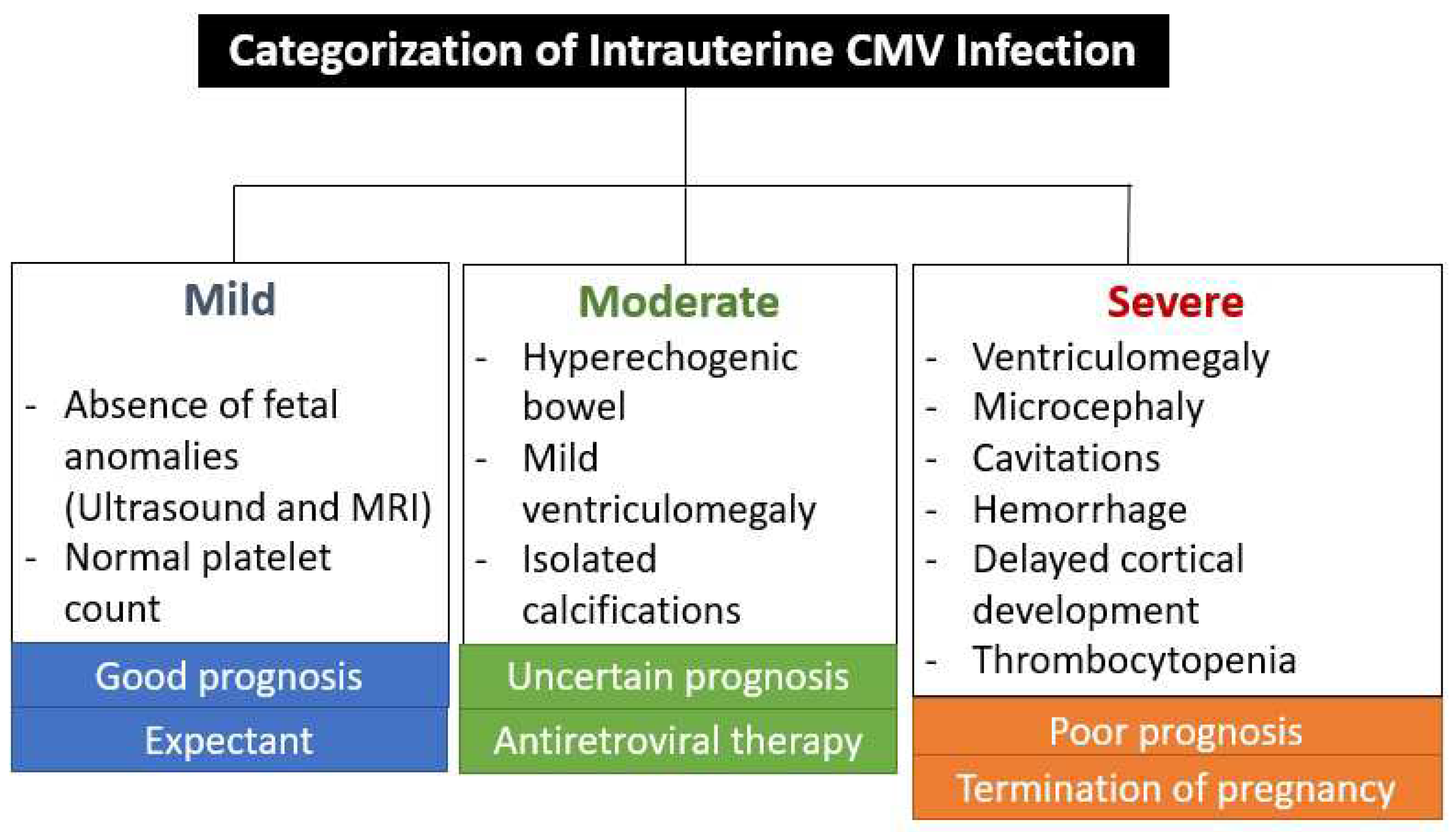

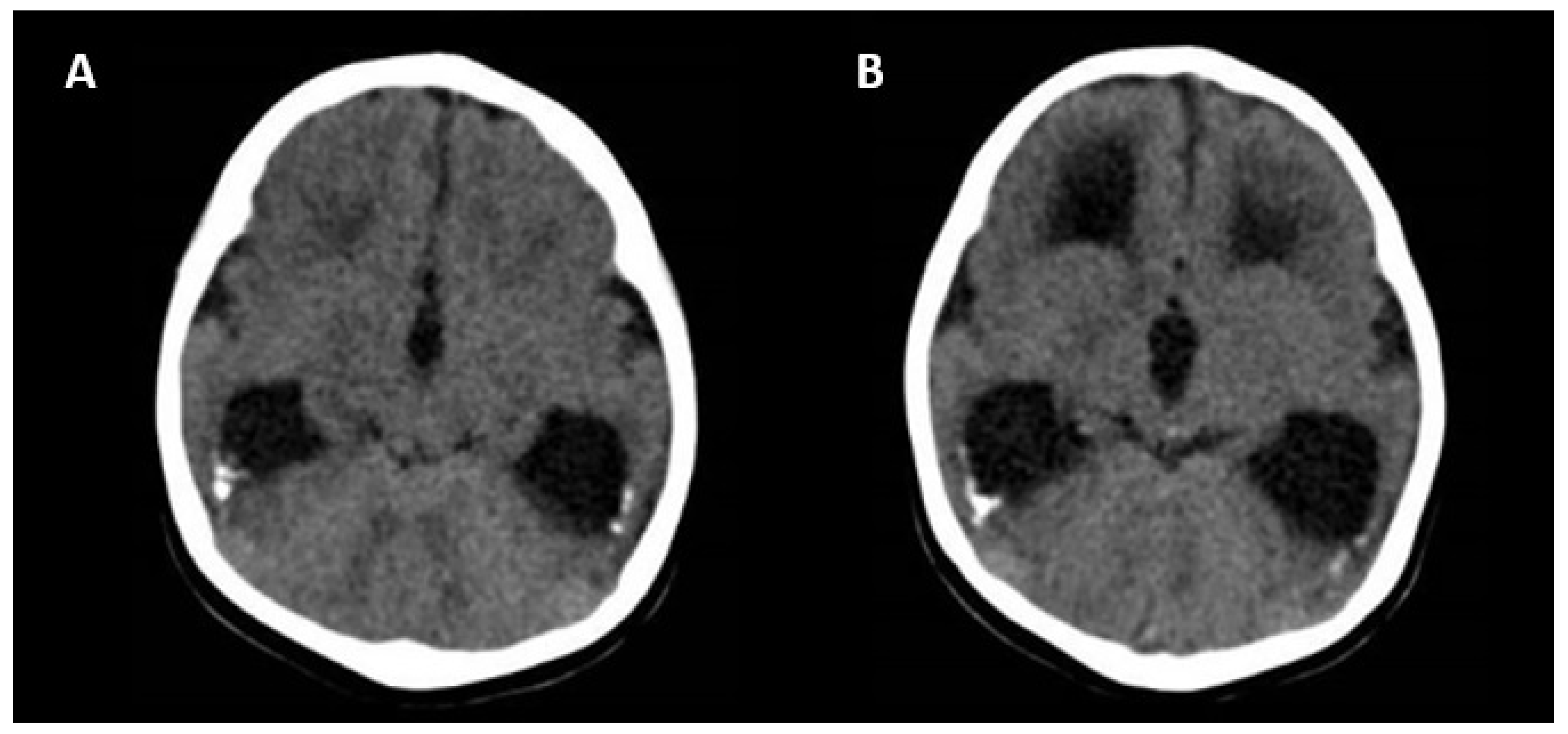

Ultrasonographic and Magnetic Resonance Imaging Findings

Diagnosis

Prognosis

Symptomatic Newborns

After delivery

Long-term sequelae

Primary Prevention

Treatment

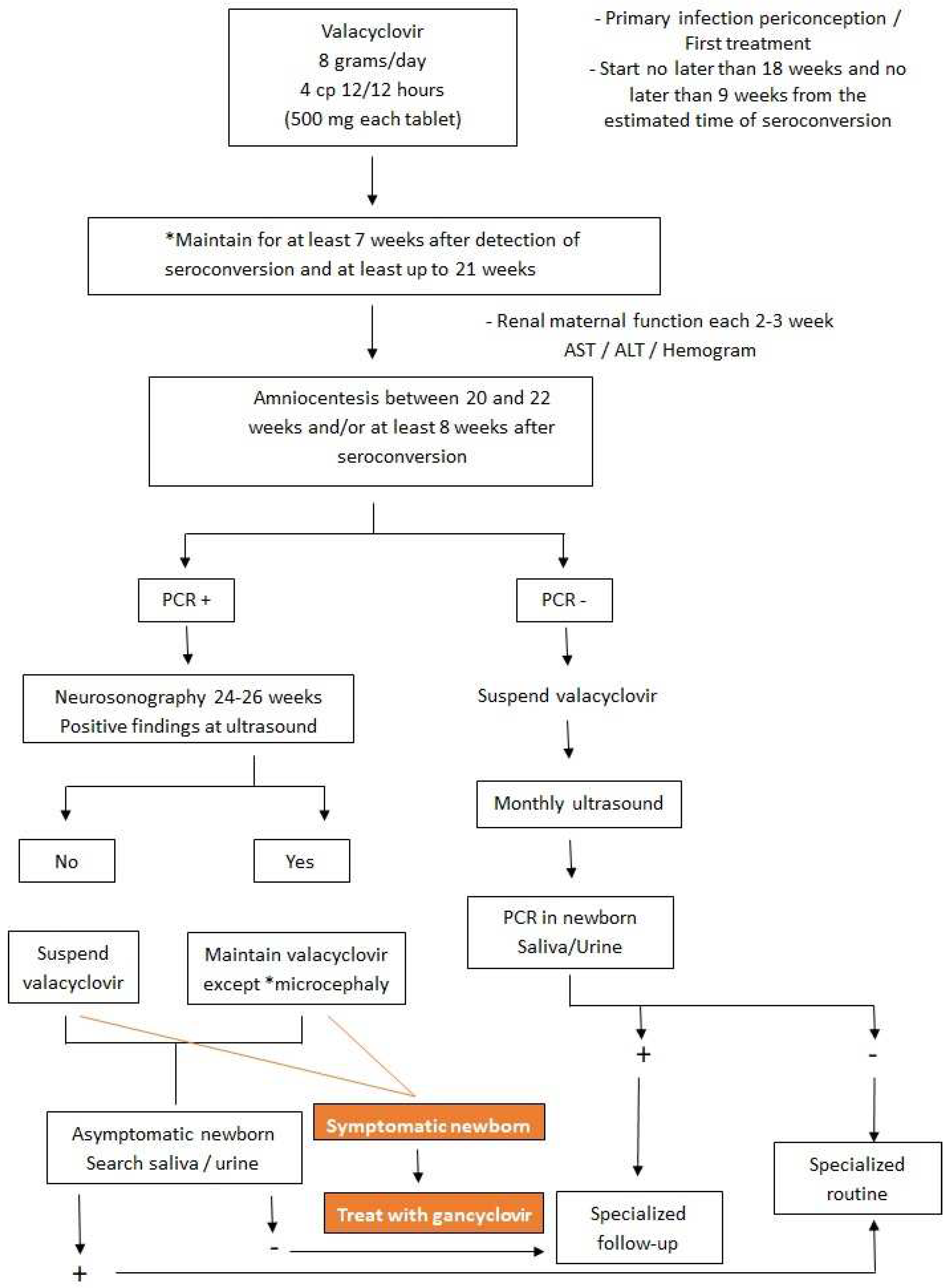

Intrauterine (Primary Prevention)

Newborn (Tertiary Prevention)

Conclusions

References

- Kenneson, A.; Cannon, M.J. Review and meta-analysis of the epidemiology of congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection. Rev Med Virol. 2007, 17, 253–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swanson EC, Schleiss. Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection: New Prospects for Pevention and Therapy. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2013, 60, 335–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zammarchi, L.; Tomasoni, L.R.; Liuzzi, G.; Simonazzi, G.; Dionisi, C.; Mazzarelli, L.L.; Seidenari, A.; Maruotti, G.M.; Ornaghi, S.; Castelli, F.; Abbate, I. Treatment with valacyclovir during pregnancy for prevention of congenital cytomegalovirus infection: a real-life multicenter Italian observacional study. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2023, 5, 101101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuhair, M.; Smit, G.S.A.; Wallis, G.; Jabbar, F.; Smith, C.; Devleesschauwer, B.; Griffiths, P. Estimation of the worldwide seroprevalence of cytomegalovirus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Med Virol. 2019, 29, e2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanzieri, T.M.; Dollard, S.C.; Bialek, S.R.; Grosse, S.D. Systematic review of the birth prevalence of congenital cytomegalovirus infection in developing countries. Int J Infect Dis. 2014, 22, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coppola, T.; Mangold, J.F.; Cantrell, S.; Permar, S.R. Impact of Maternal Immunity on Congenital Cytomegalovirus Birth Prevalence and Infant Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Vaccines 2019, 7, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mussi-Pinhata, M.M.; Yamamoto, A.Y.; Aragon, D.C.; Duarte, G.; Fowler, K.B.; Boppana, S.; Britt, W.J. Seroconversion for Cytomegalovirus Infection During Pregnancy and Fetal Infection in a Highly Seropositive Population: “The BraCHS Study”. J Infect Dis. 2018, 218, 1200–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, M.; Tripathi, T.; Holmes, N.E.; Hui, L. Serological screening for cytomegalovirus during pregnacy: A sytematic review of clinical practice guidelines and consensus statements. Prenat Diagns. 2023, 43, 959–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fowler, K.; Mucha, J.; Neumann, M.; Lewandowski, W.; Kaczanowska, M.; Grys, M.; Schmidt, E.; Natenshon, A.; Talarico, C.; Buck, P.O.; Diaz-Decaro, J. A systematic review of the global seroprevalence of cytomegalovirus: possible implications for treatment, screening, and vaccine development. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltezou, P.-G.; Kourlaba, G.; Kourkouni, E.; Luck, S.; Blázquez-Gamero, D.; Ville, Y.; Lilleri, D.; Dimopoulou, D.; Karalexi, M.; Papaevangelou, V. Maternal type of CMV infection and sequelae in infants with congenital CMV: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Virol. 2020, 129, 104518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njue, A.; Coyne, C.; Margulis, A.V.; Wang, D.; Marks, M.A.; Russell, K.; Das, R.; Sinha, A. The role of Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection in Adverse Birth Outcomes: A Review of the Potencial Machanisms. Viruses 2021, 13, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinsmoor, M.J.; Fette, L.M.; Hughes, B.L.; Rouse, D.J.; Saade, G.R.; Reddy, U.M.; Allard, D.; Mallett, G.; Thom, E.A.; Gyamfi-Bannerman, C.; et al. Amniocentesis to diagnose congenital cytomegalovirus infection following maternal primary infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2022, 4, 100641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatzakis, C.; Ville, Y.; Makrydimas, G.; Dinas, K.; Zavlanos, A.; Sotiriadis, A. Timing of primary maternal cytomegalovirus infection and rates of vertical transmission and fetal consequences. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020, 223, 870–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarthy, F.P.; Giles, M.L.; Rowlands, S.; Purcell, K.J.; Jones, C.A. Antenatal interventions for preventing the transmission of cytomegalovirus (CMV) from the mother to fetus during pregnacy and adverse outcomes in the congenitally infected infant. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011, CD008371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidel, V.; Feiterna-Sperling, C.; Siedentopf, J.-P.; Hofmann, J.; Henrich, W.; Bührer, C.; Weizsäcker, K. Intrauterine therapy of cytomegalovirus infection with valganciclovir: a review of the literature. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2017, 206, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leruez-Ville, M.; Ghout, I.; Bussières, L.; Stirnemann, J.; Magny, J.-F.; Couderc, S.; Salomon, L.J.; Guilleminot, T.; Aegerter, P.; Benoist, G.; et al. In utero treatment of congenital cytomegalovirus infection with valacyclovir in a multicenter, open-label, phase II study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016, 215, 462–e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahar-Nissan, K.; Pardo, J.; Peled, O.; Krause, I.; Bilavsky, E.; Wiznitzer, A.; Hadar, E.; Amir, J. Valacyclovir to prevent vertical transmission of cytomegalovirus after maternal primary infection during pregnancy: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2020, 396, 779–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faure-Bardon, V.; Fourgeaud, J.; Stirnemann, J.; Leruez-Ville, M. Secondary prevention of congenital cytomegalovirus infection with valacyclovir following maternal primary infection in early pregnancy. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2021, 58, 576–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egloff, C.; Sibiude, J.; Vauloup-Fellous, C.; Benachi, A.; Bouthry, E.; Biquard, F.; Hawkins-Villarreal, A.; Houhou-Fidouh, N.; Mandelbrot, L.; Vivanti, A.J.; et al. New data on efficacy of valacyclovir in secondary prevention of maternal-fetal transmission of cytomegalovirus. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2023, 61, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Antonio, F.; Marinceu, D.; Prasad, S.; Khalil, A. Effectiveness and safety of prenatal valacyclovir for congenital cytomegalovirus infection: systematic review and mata-analysis. Ultrasound obstet Gynecol. 2023, 61, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, J.; Chodick, G.; Pardo, J. Revised Protocol for Secondary, Prevention of Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection With Valacyclovir Following Infection in Early Pregnancy. Clin Infect Dis. 2023, 77, 467–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzakis, C.; Shahar-Nissan, K.; Faure-Bardon, V.; Picone, O.; Hadar, E.; Amir, J.; Egloff, C.; Vivanti, A.; Sotiriadis, A.; Leruez-Ville, M.; Ville, Y. The effect of valacyclovir on secondary prevention of congenital cytomegalovirus infection, following primary maternal infection acquired periconceptionally or in the first trimester of pregnancy. Na individual patient data meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2023, 230, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatzakis, C.; Sotiriads, A.; Dinas, K.; Ville, Y. Neonatal and long-term outcomes of infants with congenital cytimegalovirus infection and negativa amniocentesis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2023, 61, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabbri, E.; Revello, M.G.; Furione, M.; Zavattoni, M.; Lilleri, D.; Tassis, B.; Quarenghi, A.; Rustico, M.; Nicolini, U.; Ferrazzi, E.; Gerna, G. Prognstic markers of symptomatic congenital human cytomegalovirus infection in fetal blood. BJOG. 2011, 118, 448–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyriakopoulou, A.; Serghiou, S.; Dimopoulou, D.; Arista, I.; Psaltopoulou, T.; Dinopoulos, A.; Papaevangelou, V. Antenatal Imaging and clinical outcome in congenital CMV infection: a field-wide systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect. 2020, 80, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buca, D.; Di Mascio, D.; Rizzo, G.; Giancotti, A.; D'Amico, A.; Leombroni, M.; Makatsarya, A.; Familiari, A.; Liberati, M.; Nappi, L.; Flacco, M.E. Outcome of fetus with congenital cytomegalovirus infection normal ultrasound at diagnosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2021, 57, 551–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rybak-Krzyszkowska, M.; Górecka, J.; Huras, H.; Staśkiewicz, M.; Kondracka, A.; Staniczek, J.; Górczewski, W.; Borowski, D.; Grzesiak, M.; Krzeszowski, W.; et al. Ultrasonographic Signs of Cytomegalovirus Infection in the Fetus- A Systematic Review of the Literature. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvert, A.; Vandrevala, T.; Parsons, R.; Barber, V.; Book, A.; Book, G.; Carrington, D.; Greening, V.; Griffiths, P.; Hake, D.; Khalil, A. Changing knowledge, atitudes and behaviours towards cytomegalovirus in pregnancy through film-based antenatal education: a feasibility randomised controlled trial of a digital educational intervention. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021, 21, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, S.T.; van Zuylen, W.; Shand, A.; Scott, G.M.; Naing, Z.; Hall, B.; Craig, M.E.; Rawlinson, W.D. Prevention of congenital cytomegalovirus complications by maternal and neonatal treatments: a systematic review. Rev Med Virol. 2014, 24, 420–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, S.M.; Bonilla, E.; Zador, P.; Lecis, D.M.; Kilgo, C.L.; Cannon, M.J. Educating women about cytomegalovirus: assessment of health education materials through a web-based survey. BMC Women’s Health. 2014, 14, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, A.; Sotiriadis, A.; Chaoui, R.; Costa, F.d.S.; D'Antonio, F.; Heath, P.; Jones, C.; Malinger, G.; Odibo, A.; Prefumo, F.; et al. ISUOG Practice Guidelines: role of ultrasound in congenital infection. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2020, 56, 128–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Revello, M.G.; Lazzarotto, T.; Guerra, B.; Spinillo, A.; Ferrazzi, E.; Kustermann, A.; Guaschino, S.; Vergani, P.; Todros, T.; Frusca, T.; Arossa, A. A Randomized of hyperimmune Globulin to Prevent Congeniatl Cytomegalovirus. N Engl J Med. 2014, 370, 1316–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, V.; Calvert, A.; Vandrevala, T.; Star, C.; Khalil, A.; Griffiths, P.; Heath, P.T.; Jones, C.E. Prevention o Acquisition of Cytomegalovirus Infection in Pregnancy Through Hygiene-based Behavioral Interventions: A Systematic Review and Gap Analysis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2020, 39, 949–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devlieger, R.; Buxmann, H.; Nigro, G.; Enders, M.; Jückstock, J.; Siklos, P.; Wartenberg-Demand, A.; Schüttrumpf, J.; Schütze, J.; Rippel, N.; Herbold, M. Serial Monitoring and Hyperimmunoglobilin versus oo Care to Prevent Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection: A Phase III Randomized Trial. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2021, 48, 611–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Qushayri, A.E.; Ghozy, S.; Abbas, A.S.; Dibas, M.; Dahy, A.; Mahmoud, A.R.; Afifi, A.M.; El-Khazragy, N. Hyperimmunoglobulin therapy for the prevention and treatment of congenital cytomegalovirus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2021, 19, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, A.; Cooper, C.; Vasilunas, N.; Ritchie, B. Describing the Impact of Maternal Hyperimmune Globilin and Valacyclovir in Pregnacy: A Systematic Review. Clin Infect Dis. 2022, 75, 1467–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes BL, Clifton RG, Rouse DJ, Saade GR, Dinsmoor MJ, Reddy UM, et al. A Trial of Hyperimmune Globulin to Prevent Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection. N Engl J Med. 2021, 385, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benou, S.; Dimitriou, G.; Papaevangelou, V.; Gkentzi, D. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection: do pregnant women and healthcare providers know enough? A systematic review. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2022, 35, 6566–6575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of infection | Definition |

|---|---|

| Confirmed primary infection | IgG and IgM negative previously, showing serum conversion during pregnancy* |

| Presumed primary infection | CMV IgG+, with low avidity** and IgM+, in the first trimester or CMV IgG and M+, with undetermined IgG avidity, with detection of CMV-DNA in at least 1 body fluid (blood, urine or saliva) during pregnancy |

| False positive | IgM+ and IgG negative in paired tests with a difference of at least 2 weeks* |

|

Confirmed non-primary infection |

CMV IgG+ before pregnancy or CMV IgG+ and IgM negative in the 1st trimester |

|

Presumed non-primary infection |

CMV IgM negative and 1- IgG+ before 12 weeks with unknown IgM or 2- Four times increase in IgG titers in paired tests |

|

Congenital CMV infection |

Detection of CMV (culture) or CMV-DNA by PCR in the newborn's saliva, urine or blood obtained up to 3 weeks of age or in the amniotic fluid.[2] |

| Extra-CNS | |

| FGR Abnormal amniotic fluid volume Ascites and/or pleural effusion Skin edema Hydrops Placentomegaly >40 mm Hyperechogenic intestines Hepatomegaly >40 mm (right lobe) Splenomegaly >40 mm (largest diameter in the second trimester) Hepatic calcifications Cardiomegaly |

|

| CNS | |

| Moderate ventriculomegaly <15 mm Isolated cerebral calcification Isolated interventricular adhesion Vasculopathy/hyperechogenicity of lenticulostriate vessels |

|

| Severe CNS malformations | |

| Ventriculomegaly >15 mm Periventricular hyperechogenicity Hydrocephalus Microcephaly <3 SD Mega cisterna magna >10 mm Hypoplasia of vernix or cerebellum Porencephaly Lissencephaly Periventricular cysts Corpus callosum abnormality |

| Criteria for poor intrauterine prognosis | |

| Cordocentesis | |

| Viral load >30,000 copies/mL Platelets <50,000mm3 Increased ß2-microglubulin High levels of specific IgM |

|

| Ultrasound or MRI | |

| Microcephaly | |

| Time of maternal infection | |

| Periconceptional - 4 weeks before the last menstrual period up to 3 weeks of gestation* First trimester |

|

| Amniocentesis | |

| Positive PCR for CMV with high viral replication |

| Period of primary infection or other serological status | CMV-specific antibodies | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| IgG | IgM | IgG avidity | |

| >12 weeks | + | + | High |

| Periconceptional infection | + | + | Intermediate |

| Infection in the first trimester of pregnancy* | + | + | Low |

| - | + | x | |

| No prior contact | - | - | x |

| False positive test** | - | + | x |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).