Submitted:

25 December 2023

Posted:

28 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

REDUCED CANCER RISK IN GENETIC SYNDROMIC CONDITIONS

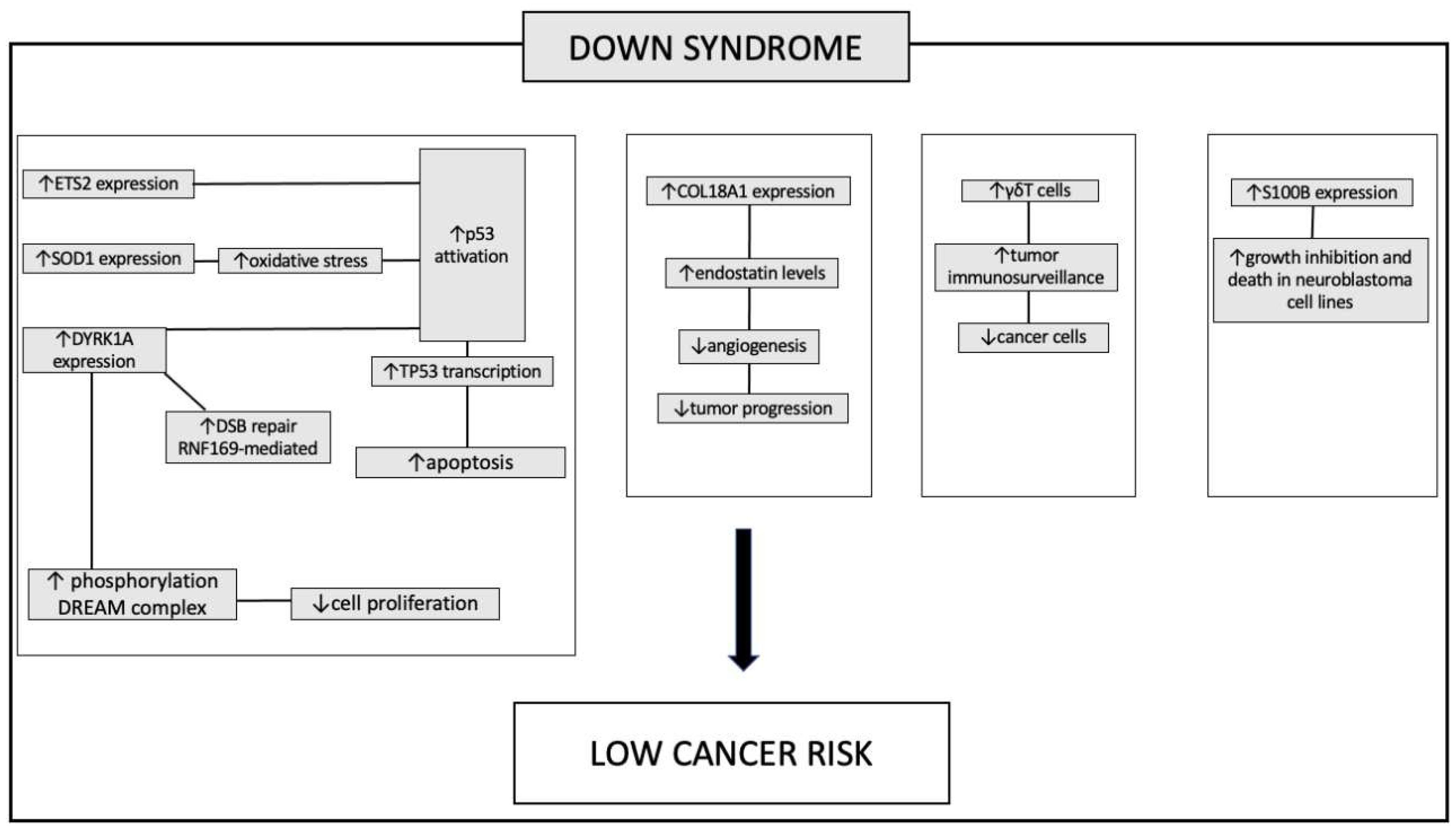

Down syndrome

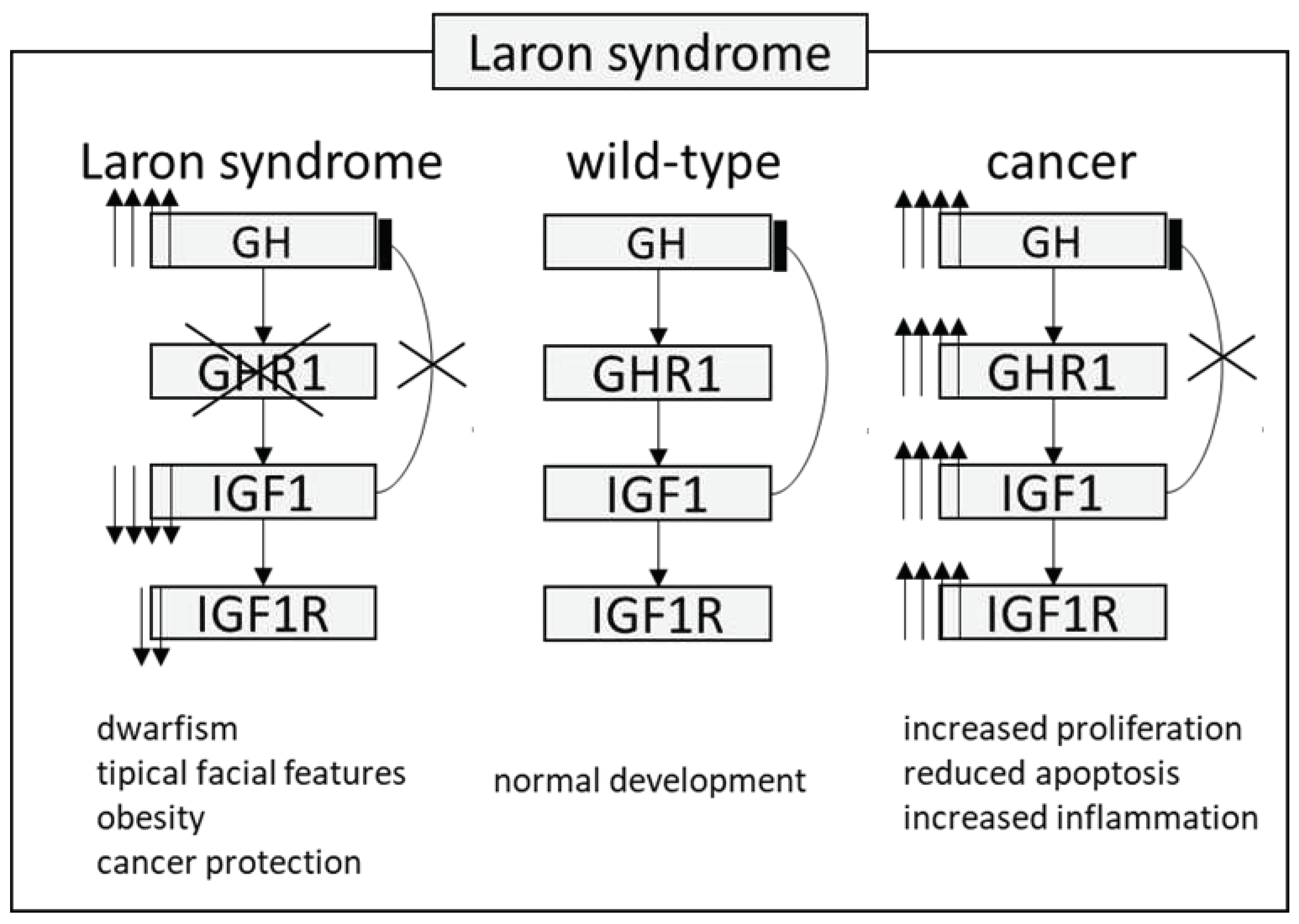

Laron Syndrome

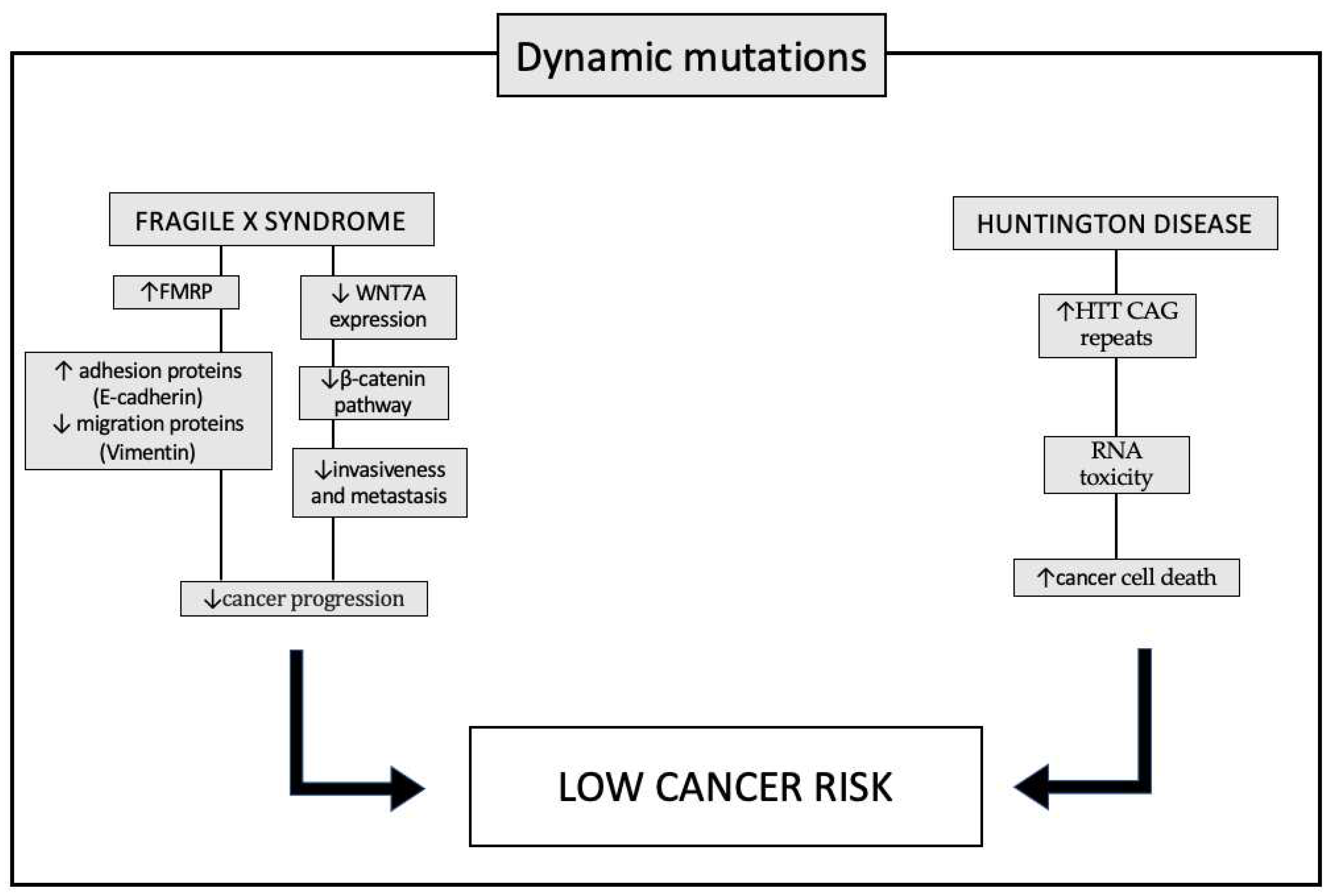

REDUCED CANCER RISK IN SYNDROMES WITH DYNAMIC MUTATIONS

HEREDITARY CANCER SYNDROMES

Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer Syndrome

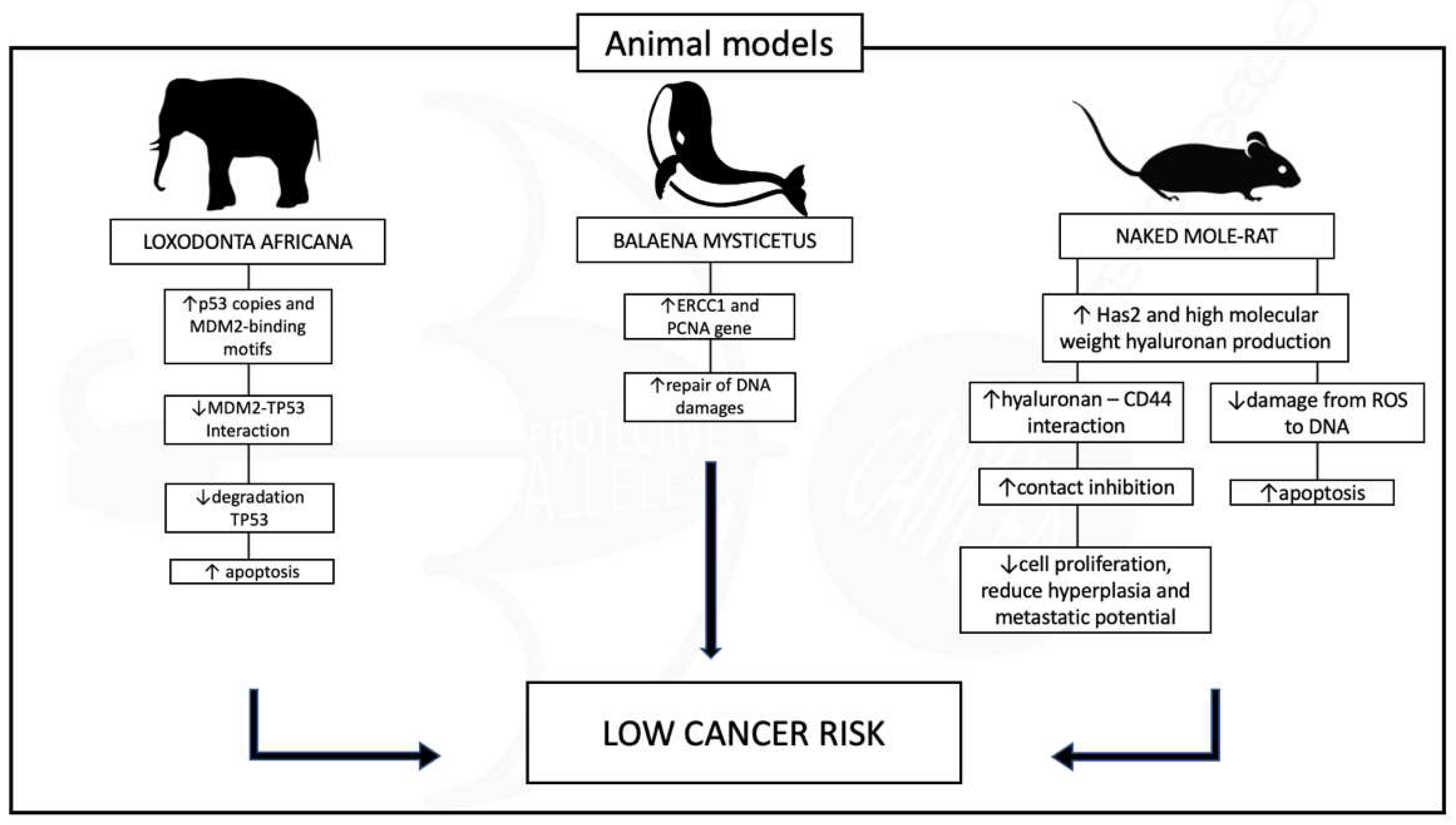

REDUCED CANCER RISK THROUGHOUT THE ANIMAL KINGDOM

Conclusions

References

- Lane, I.W.; Comac, L. Sharks Don’t Get Cancer, 1st edition.; Avery Pub Group: Garden City Park, N.Y, 1992; ISBN 978-0-89529-520-0. [Google Scholar]

- Loprinzi, C.L.; Levitt, R.; Barton, D.L.; Sloan, J.A.; Atherton, P.J.; Smith, D.J.; Dakhil, S.R.; Moore, D.F.; Krook, J.E.; Rowland, K.M.; et al. Evaluation of Shark Cartilage in Patients with Advanced Cancer: A North Central Cancer Treatment Group Trial. Cancer 2005, 104, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peto, R.; Roe, F.J.; Lee, P.N.; Levy, L.; Clack, J. Cancer and Ageing in Mice and Men. Br J Cancer 1975, 32, 411–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tollis, M.; Boddy, A.M.; Maley, C.C. Peto’s Paradox: How Has Evolution Solved the Problem of Cancer Prevention? BMC Biology 2017, 15, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Futreal, P.A.; Liu, Q.; Shattuck-Eidens, D.; Cochran, C.; Harshman, K.; Tavtigian, S.; Bennett, L.M.; Haugen-Strano, A.; Swensen, J.; Miki, Y. BRCA1 Mutations in Primary Breast and Ovarian Carcinomas. Science 1994, 266, 120–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miki, Y.; Swensen, J.; Shattuck-Eidens, D.; Futreal, P.A.; Harshman, K.; Tavtigian, S.; Liu, Q.; Cochran, C.; Bennett, L.M.; Ding, W. A Strong Candidate for the Breast and Ovarian Cancer Susceptibility Gene BRCA1. Science 1994, 266, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narod, S.A.; Foulkes, W.D. BRCA1 and BRCA2: 1994 and Beyond. Nat Rev Cancer 2004, 4, 665–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fong, P.C.; Boss, D.S.; Yap, T.A.; Tutt, A.; Wu, P.; Mergui-Roelvink, M.; Mortimer, P.; Swaisland, H.; Lau, A.; O’Connor, M.J.; et al. Inhibition of Poly(ADP-Ribose) Polymerase in Tumors from BRCA Mutation Carriers. N Engl J Med 2009, 361, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golan, T.; Hammel, P.; Reni, M.; Van Cutsem, E.; Macarulla, T.; Hall, M.J.; Park, J.-O.; Hochhauser, D.; Arnold, D.; Oh, D.-Y.; et al. Maintenance Olaparib for Germline BRCA-Mutated Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer. N Engl J Med 2019, 381, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litton, J.K.; Rugo, H.S.; Ettl, J.; Hurvitz, S.A.; Gonçalves, A.; Lee, K.-H.; Fehrenbacher, L.; Yerushalmi, R.; Mina, L.A.; Martin, M.; et al. Talazoparib in Patients with Advanced Breast Cancer and a Germline BRCA Mutation. N Engl J Med 2018, 379, 753–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, A.R.; Nayee, S.; Topol, E.J. Protective Alleles and Modifier Variants in Human Health and Disease. Nature Reviews Genetics 2015, 16, 689–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeau, J.H.; Topol, E.J. The Genetics of Health. Nature Genetics 2006, 38, 1095–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raal, F.J.; Kallend, D.; Ray, K.K.; Turner, T.; Koenig, W.; Wright, R.S.; Wijngaard, P.L.J.; Curcio, D.; Jaros, M.J.; Leiter, L.A.; et al. Inclisiran for the Treatment of Heterozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia. N Engl J Med 2020, 382, 1520–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giugliano, R.P.; Pedersen, T.R.; Park, J.-G.; De Ferrari, G.M.; Gaciong, Z.A.; Ceska, R.; Toth, K.; Gouni-Berthold, I.; Lopez-Miranda, J.; Schiele, F.; et al. Clinical Efficacy and Safety of Achieving Very Low LDL-Cholesterol Concentrations with the PCSK9 Inhibitor Evolocumab: A Prespecified Secondary Analysis of the FOURIER Trial. Lancet 2017, 390, 1962–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narasimhan, V.M.; Hunt, K.A.; Mason, D.; Baker, C.L.; Karczewski, K.J.; Barnes, M.R.; Barnett, A.H.; Bates, C.; Bellary, S.; Bockett, N.A.; et al. Health and Population Effects of Rare Gene Knockouts in Adult Humans with Related Parents. Science 2016, 352, 474–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleheen, D.; Natarajan, P.; Armean, I.M.; Zhao, W.; Rasheed, A.; Khetarpal, S.A.; Won, H.-H.; Karczewski, K.J.; O’Donnell-Luria, A.H.; Samocha, K.E.; et al. Human Knockouts and Phenotypic Analysis in a Cohort with a High Rate of Consanguinity. Nature 2017, 544, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, R.; Wang, S.; Zhang, S.; Zeng, H.; Chen, R.; Sun, K.; Li, L.; Bray, F.; Wei, W. Global, Regional, and National Lifetime Probabilities of Developing Cancer in 2020. Sci Bull (Beijing), 2095; S2095-9273(23)00676-X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Ek, W.E.; Whiteman, D.; Vaughan, T.L.; Spurdle, A.B.; Easton, D.F.; Pharoah, P.D.; Thompson, D.J.; Dunning, A.M.; Hayward, N.K.; et al. Most Common “sporadic” Cancers Have a Significant Germline Genetic Component. Hum Mol Genet 2014, 23, 6112–6118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Launer, J. Winston Churchill and His Illnesses. Postgraduate Medical Journal 2021, 97, 135–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manor, J.; Lalani, S.R. Overgrowth Syndromes-Evaluation, Diagnosis, and Management. Front Pediatr 2020, 8, 574857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recommendations for Cancer Surveillance in Individuals with RASopathies and Other Rare Genetic Conditions with Increased Cancer Risk | Clinical Cancer Research | American Association for Cancer Research. Available online: https://aacrjournals.org/clincancerres/article/23/12/e83/80230/Recommendations-for-Cancer-Surveillance-in (accessed on 30 October 2023).

- Tamura, R. Current Understanding of Neurofibromatosis Type 1, 2, and Schwannomatosis. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 5850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, I.M.; Sheppard, S.E.; Crowley, T.B.; McGinn, D.E.; Bailey, A.; McGinn, M.J.; Unolt, M.; Homans, J.F.; Chen, E.Y.; Salmons, H.I.; et al. What Is New with 22q? An Update from the 22q and You Center at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A 2018, 176, 2058–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasle, H.; Friedman, J.M.; Olsen, J.H.; Rasmussen, S.A. Low Risk of Solid Tumors in Persons with Down Syndrome. Genetics in Medicine 2016, 18, 1151–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dey, N.; Krie, A.; Klein, J.; Williams, K.; McMillan, A.; Elsey, R.; Sun, Y.; Williams, C.; De, P.; Leyland-Jones, B. Down’s Syndrome and Triple Negative Breast Cancer: A Rare Occurrence of Distinctive Clinical Relationship. Int J Mol Sci 2017, 18, 1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nižetić, D.; Groet, J. Tumorigenesis in Down’s Syndrome: Big Lessons from a Small Chromosome. Nat Rev Cancer 2012, 12, 721–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolvetang, E.J.; Bradfield, O.M.; Hatzistavrou, T.; Crack, P.J.; Busciglio, J.; Kola, I.; Hertzog, P.J. Overexpression of the Chromosome 21 Transcription Factor Ets2 Induces Neuronal Apoptosis. Neurobiol Dis 2003, 14, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- C, M.-B.; C, C.; C, T.; J, J.; C, M. [Trisomy 21 and Breast Cancer: A Genetic Abnormality Which Protects against Breast Cancer?]. Gynecologie, obstetrique & fertilite 2016, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sussan, T.E.; Yang, A.; Li, F.; Ostrowski, M.C.; Reeves, R.H. Trisomy Represses Apc(Min)-Mediated Tumours in Mouse Models of Down’s Syndrome. Nature 2008, 451, 73–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagano, G.; Castello, G. Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Down Syndrome. Adv Exp Med Biol 2012, 724, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinha, S. Anti-Oxidant Gene Expression Imbalance, Aging and Down Syndrome. Life Sci 2005, 76, 1407–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryeom, S.; Baek, K.-H.; Zaslavsky, A. Down’s Syndrome: Protection against Cancer and the Therapeutic Potential of DSCR1. Future Oncol 2009, 5, 1185–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- High Serum Endostatin Levels in Down Syndrome: Implications for Improved Treatment and Prevention of Solid Tumours - PubMed. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11781696/ (accessed on 21 December 2023).

- Hämmerle, B.; Elizalde, C.; Galceran, J.; Becker, W.; Tejedor, F.J. The MNB/DYRK1A Protein Kinase: Neurobiological Functions and Down Syndrome Implications. J Neural Transm Suppl 2003, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinge, S.; Bliss-Moreau, M.; Kirsammer, G.; Diebold, L.; Chlon, T.; Gurbuxani, S.; Crispino, J.D. Increased Dosage of the Chromosome 21 Ortholog Dyrk1a Promotes Megakaryoblastic Leukemia in a Murine Model of Down Syndrome. J Clin Invest 2012, 122, 948–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arron, J.R.; Winslow, M.M.; Polleri, A.; Chang, C.-P.; Wu, H.; Gao, X.; Neilson, J.R.; Chen, L.; Heit, J.J.; Kim, S.K.; et al. NFAT Dysregulation by Increased Dosage of DSCR1 and DYRK1A on Chromosome 21. Nature 2006, 441, 595–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozen, E.J.; Roewenstrunk, J.; Barallobre, M.J.; Di Vona, C.; Jung, C.; Figueiredo, A.F.; Luna, J.; Fillat, C.; Arbonés, M.L.; Graupera, M.; et al. DYRK1A Kinase Positively Regulates Angiogenic Responses in Endothelial Cells. Cell Rep 2018, 23, 1867–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.; Oh, Y.; Yoo, L.; Jung, M.-S.; Song, W.-J.; Lee, S.-H.; Seo, H.; Chung, K.C. Dyrk1A Phosphorylates P53 and Inhibits Proliferation of Embryonic Neuronal Cells. J Biol Chem 2010, 285, 31895–31906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litovchick, L.; Florens, L.A.; Swanson, S.K.; Washburn, M.P.; DeCaprio, J.A. DYRK1A Protein Kinase Promotes Quiescence and Senescence through DREAM Complex Assembly. Genes Dev 2011, 25, 801–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez de Lagran, M.; Benavides-Piccione, R.; Ballesteros-Yañez, I.; Calvo, M.; Morales, M.; Fillat, C.; Defelipe, J.; Ramakers, G.J.A.; Dierssen, M. Dyrk1A Influences Neuronal Morphogenesis through Regulation of Cytoskeletal Dynamics in Mammalian Cortical Neurons. Cereb Cortex 2012, 22, 2867–2877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fotaki, V.; Dierssen, M.; Alcántara, S.; Martínez, S.; Martí, E.; Casas, C.; Visa, J.; Soriano, E.; Estivill, X.; Arbonés, M.L. Dyrk1A Haploinsufficiency Affects Viability and Causes Developmental Delay and Abnormal Brain Morphology in Mice. Mol Cell Biol 2002, 22, 6636–6647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.E.; Xing, Z.; Do, C.; Pao, A.; Lee, E.J.; Krinsky-McHale, S.; Silverman, W.; Schupf, N.; Tycko, B. Genetic and Epigenetic Pathways in Down Syndrome: Insights to the Brain and Immune System from Humans and Mouse Models. Prog Brain Res 2020, 251, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brás, A.; Rodrigues, A.S.; Gomes, B.; Rueff, J. Down Syndrome and microRNAs. Biomed Rep 2018, 8, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, L.A.; Bialowas-McGoey, L.A.; Whitaker-Azmitia, P.M. Effects of S100B on Serotonergic Plasticity and Neuroinflammation in the Hippocampus in Down Syndrome and Alzheimer’s Disease: Studies in an S100B Overexpressing Mouse Model. Cardiovasc Psychiatry Neurol 2010, 2010, 153657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rethoré, M.-O.; Rouëssé, J.; Satgé, D. Cancer Screening in Adults with down Syndrome, a Proposal. European Journal of Medical Genetics 2020, 63, 103783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, J.P.; Cooper, C.S. ETS Gene Fusions in Prostate Cancer. Nat Rev Urol 2009, 6, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laron, Z. Syndrome of Familial Dwarfism and High Plasma Immunoreactive Growth Hormone. Isr J Med Sci 1974, 10, 1247–1253. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Amselem, S.; Duquesnoy, P.; Attree, O.; Novelli, G.; Bousnina, S.; Postel-Vinay, M.C.; Goossens, M. Laron Dwarfism and Mutations of the Growth Hormone-Receptor Gene. N Engl J Med 1989, 321, 989–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shevah, O.; Laron, Z. Patients with Congenital Deficiency of IGF-I Seem Protected from the Development of Malignancies: A Preliminary Report. Growth Horm IGF Res 2007, 17, 54–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clayton, P.E.; Banerjee, I.; Murray, P.G.; Renehan, A.G. Growth Hormone, the Insulin-like Growth Factor Axis, Insulin and Cancer Risk. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2011, 7, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guevara-Aguirre, J.; Balasubramanian, P.; Guevara-Aguirre, M.; Wei, M.; Madia, F.; Cheng, C.-W.; Hwang, D.; Martin-Montalvo, A.; Saavedra, J.; Ingles, S.; et al. Growth Hormone Receptor Deficiency Is Associated with a Major Reduction in Pro-Aging Signaling, Cancer, and Diabetes in Humans. Sci Transl Med 2011, 3, 70ra13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner, H.; Lapkina-Gendler, L.; Achlaug, L.; Nagaraj, K.; Somri, L.; Yaron-Saminsky, D.; Pasmanik-Chor, M.; Sarfstein, R.; Laron, Z.; Yakar, S. Genome-Wide Profiling of Laron Syndrome Patients Identifies Novel Cancer Protection Pathways. Cells 2019, 8, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somri, L.; Sarfstein, R.; Lapkina-Gendler, L.; Nagaraj, K.; Laron, Z.; Bach, L.A.; Werner, H. Differential Expression of IGFBPs in Laron Syndrome-Derived Lymphoblastoid Cell Lines: Potential Correlation with Reduced Cancer Incidence. Growth Horm IGF Res 2018, 39, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinkston, J.M.; Garigan, D.; Hansen, M.; Kenyon, C. Mutations That Increase the Life Span of C. Elegans Inhibit Tumor Growth. Science 2006, 313, 971–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimberg, A. Mechanisms by Which IGF-I May Promote Cancer. Cancer Biol Ther 2003, 2, 630–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Xu, B.C.; Maheshwari, H.G.; He, L.; Reed, M.; Lozykowski, M.; Okada, S.; Cataldo, L.; Coschigamo, K.; Wagner, T.E.; et al. A Mammalian Model for Laron Syndrome Produced by Targeted Disruption of the Mouse Growth Hormone Receptor/Binding Protein Gene (the Laron Mouse). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1997, 94, 13215–13220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ter Braak, B.; Siezen, C.; Speksnijder, E.N.; Koedoot, E.; van Steeg, H.; Salvatori, D.C.F.; van de Water, B.; van der Laan, J.W. Mammary Gland Tumor Promotion by Chronic Administration of IGF1 and the Insulin Analogue AspB10 in the p53R270H/+WAPCre Mouse Model. Breast Cancer Res 2015, 17, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unterberger, C.J.; McGregor, S.M.; Kopchick, J.J.; Swanson, S.M.; Marker, P.C. Mammary Tumor Growth and Proliferation Are Dependent on Growth Hormone in Female SV40 C3(1) T-Antigen Mice. Endocrinology 2022, 164, bqac174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfaro-Arnedo, E.; López, I.P.; Piñeiro-Hermida, S.; Canalejo, M.; Gotera, C.; Sola, J.J.; Roncero, A.; Peces-Barba, G.; Ruíz-Martínez, C.; Pichel, J.G. IGF1R Acts as a Cancer-Promoting Factor in the Tumor Microenvironment Facilitating Lung Metastasis Implantation and Progression. Oncogene 2022, 41, 3625–3639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobile, V.; Pucci, C.; Chiurazzi, P.; Neri, G.; Tabolacci, E. DNA Methylation, Mechanisms of FMR1 Inactivation and Therapeutic Perspectives for Fragile X Syndrome. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz-Pedersen, S.; Hasle, H.; Olsen, J.H.; Friedrich, U. Evidence of Decreased Risk of Cancer in Individuals with Fragile X. Am J Med Genet 2001, 103, 226–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sund, R.; Pukkala, E.; Patja, K. Cancer Incidence among Persons with Fragile X Syndrome in Finland: A Population-Based Study. J Intellect Disabil Res 2009, 53, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucá, R.; Averna, M.; Zalfa, F.; Vecchi, M.; Bianchi, F.; La Fata, G.; Del Nonno, F.; Nardacci, R.; Bianchi, M.; Nuciforo, P.; et al. The Fragile X Protein Binds mRNAs Involved in Cancer Progression and Modulates Metastasis Formation. EMBO Mol Med 2013, 5, 1523–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gene Expression Profiling Identifies WNT7A as a Possible Candidate Gene for Decreased Cancer Risk in Fragile X Syndrome Patients - PubMed. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20470940/ (accessed on 30 October 2023).

- McNulty, P.; Pilcher, R.; Ramesh, R.; Necuiniate, R.; Hughes, A.; Farewell, D.; Holmans, P.; Jones, L. ; REGISTRY Investigators of the European Huntington’s Disease Network Reduced Cancer Incidence in Huntington’s Disease: Analysis in the Registry Study. J Huntingtons Dis 2018, 7, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.R.; Goldacre, R.; Goldacre, M.J. Reduced Cancer Incidence in Huntington’s Disease: Record Linkage Study Clue to an Evolutionary Trade-Off? Clin Genet 2013, 83, 588–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehret, J.C.; Day, P.S.; Wiegand, R.; Wojcieszek, J.; Chambers, R.A. Huntington Disease as a Dual Diagnosis Disorder: Data from the National Research Roster for Huntington Disease Patients and Families. Drug Alcohol Depend 2007, 86, 283–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thion, M.S.; Tézenas du Montcel, S.; Golmard, J.-L.; Vacher, S.; Barjhoux, L.; Sornin, V.; Cazeneuve, C.; Bièche, I.; Sinilnikova, O.; Stoppa-Lyonnet, D.; et al. CAG Repeat Size in Huntingtin Alleles Is Associated with Cancer Prognosis. Eur J Hum Genet 2016, 24, 1310–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murmann, A.E.; Gao, Q.Q.; Putzbach, W.E.; Patel, M.; Bartom, E.T.; Law, C.Y.; Bridgeman, B.; Chen, S.; McMahon, K.M.; Thaxton, C.S.; et al. Small Interfering RNAs Based on Huntingtin Trinucleotide Repeats Are Highly Toxic to Cancer Cells. EMBO Rep 2018, 19, e45336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garutti, M.; Foffano, L.; Mazzeo, R.; Michelotti, A.; Da Ros, L.; Viel, A.; Miolo, G.; Zambelli, A.; Puglisi, F. Hereditary Cancer Syndromes: A Comprehensive Review with a Visual Tool. Genes (Basel) 2023, 14, 1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, X.; Chen, L.; Yang, A.; Lv, Z.; Xiong, M.; Shan, C. ADRB2 Is a Potential Protective Gene in Breast Cancer by Regulating Tumor Immune Microenvironment. Transl Cancer Res 2021, 10, 5280–5294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamson, A.W.; Ding, Y.C.; Mendez-Dorantes, C.; Bailis, A.M.; Stark, J.M.; Neuhausen, S.L. The RAD52 S346X Variant Reduces Risk of Developing Breast Cancer in Carriers of Pathogenic Germline BRCA2 Mutations. Mol Oncol 2020, 14, 1124–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biswas, K.; Sharan, S.K. RAD52 S346X Variant Reduces Breast Cancer Risk in BRCA2 Mutation Carriers. Mol Oncol 2020, 14, 1121–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abegglen, L.M.; Caulin, A.F.; Chan, A.; Lee, K.; Robinson, R.; Campbell, M.S.; Kiso, W.K.; Schmitt, D.L.; Waddell, P.J.; Bhaskara, S.; et al. Potential Mechanisms for Cancer Resistance in Elephants and Comparative Cellular Response to DNA Damage in Humans. JAMA 2015, 314, 1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez, J.M.; Sulak, M.; Chigurupati, S.; Lynch, V.J. A Zombie LIF Gene in Elephants Is Upregulated by TP53 to Induce Apoptosis in Response to DNA Damage. Cell Rep 2018, 24, 1765–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padariya, M.; Jooste, M.-L.; Hupp, T.; Fåhraeus, R.; Vojtesek, B.; Vollrath, F.; Kalathiya, U.; Karakostis, K. The Elephant Evolved P53 Isoforms That Escape MDM2-Mediated Repression and Cancer. Mol Biol Evol 2022, 39, msac149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Formica, V.; Doldo, E.; Antonetti, F.R.; Nardecchia, A.; Ferroni, P.; Riondino, S.; Morelli, C.; Arkenau, H.T.; Guadagni, F.; Orlandi, A.; et al. Biological and Predictive Role of ERCC1 Polymorphisms in Cancer. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology 2017, 111, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keane, M.; Semeiks, J.; Webb, A.E.; Li, Y.I.; Quesada, V.; Craig, T.; Madsen, L.B.; van Dam, S.; Brawand, D.; Marques, P.I.; et al. Insights into the Evolution of Longevity from the Bowhead Whale Genome. Cell Rep 2015, 10, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoege, C.; Pfander, B.; Moldovan, G.-L.; Pyrowolakis, G.; Jentsch, S. RAD6-Dependent DNA Repair Is Linked to Modification of PCNA by Ubiquitin and SUMO. Nature 2002, 419, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanno, M.; Ogihara, M.; Taguchi, T. Age-Related Changes in Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen Levels. Mech Ageing Dev 1996, 92, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorbunova, V.; Bozzella, M.J.; Seluanov, A. Rodents for Comparative Aging Studies: From Mice to Beavers. Age (Dordr) 2008, 30, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, X.; Azpurua, J.; Hine, C.; Vaidya, A.; Myakishev-Rempel, M.; Ablaeva, J.; Mao, Z.; Nevo, E.; Gorbunova, V.; Seluanov, A. High-Molecular-Mass Hyaluronan Mediates the Cancer Resistance of the Naked Mole Rat. Nature 2013, 499, 346–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takasugi, M.; Ohtani, N.; Takemura, K.; Emmrich, S.; Zakusilo, F.T.; Yoshida, Y.; Kutsukake, N.; Mariani, J.N.; Windrem, M.S.; Chandler-Militello, D.; et al. CD44 Correlates with Longevity and Enhances Basal ATF6 Activity and ER Stress Resistance. Cell Rep 2023, 42, 113130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, X.; Azpurua, J.; Ke, Z.; Augereau, A.; Zhang, Z.D.; Vijg, J.; Gladyshev, V.N.; Gorbunova, V.; Seluanov, A. INK4 Locus of the Tumor-Resistant Rodent, the Naked Mole Rat, Expresses a Functional P15/P16 Hybrid Isoform. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015, 112, 1053–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Tian, X.; Lu, J.Y.; Boit, K.; Ablaeva, J.; Zakusilo, F.T.; Emmrich, S.; Firsanov, D.; Rydkina, E.; Biashad, S.A.; et al. Increased Hyaluronan by Naked Mole-Rat Has2 Improves Healthspan in Mice. Nature 2023, 621, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangarajan, A.; Hong, S.J.; Gifford, A.; Weinberg, R.A. Species- and Cell Type-Specific Requirements for Cellular Transformation. Cancer Cell 2004, 6, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).