1. Introduction

Construction work is challenging due to the unique nature of construction projects, and construction project management requires the application of knowledge to meet project requirements [

1]. It is common for construction teams to seek additional knowledge to complete work tasks because of the dynamic and complex nature of construction projects [

2]. Since the knowledge needed to complete a construction project is held by project team members, knowledge sharing is crucial to integrate distributed knowledge and achieve project performance [

1]. Other critical elements in construction are the communication and coordination between team members on a construction site [

3,

4].

Three project management-based theories have been applied in the project context: stakeholder management theory, social exchange theory, and knowledge-based theory [

6,65,66]. From the standpoint of work organizations, SM has emerged as a valuable information channel, allowing employees to search for and access relevant information through collaborative efforts [

8]. According to Ma et al. [

9], Kanagarajoo et al. [

10], using SM at work has positive effects on team processes such as communication, knowledge sharing, and coordination. In addition, the created perception of social presence/intimacy [

11], and real-time/ immediacy transparency [

12], are emphasized as a strong argument for organizations using SM in projects. There is limited knowledge about how SM use affects employees in the construction industry [

13]. Using SM for project management creates several limitations, including (1)

behavioral (a "write first, think later" tendency; a lack of focus and direction in discussions); (2)

cognitive (impaired decision-making due to a lack of appropriate and complete information); and (3)

environmental (management of access control and accountabilities; information leakage) [

14,

15], limitations are the other limitations that create by using SM for project management [

16]. Other limitations to adoption include the lack of trustworthiness, confidentiality/ privacy [44], the leakage of sensitive key project data is among the biggest threats [

15], the lack of clarity of ownership of technical infrastructure (many people blend private devices, accounts on platforms, etc.) or inclusive SM rules, software breakdown problems, resistance from older staff members, and data synchronization problems, according to [

18].

Furthermore, previous studies suggest that using innovative information technologies is a common approach to enhance team processes in construction projects [

19,

20]. Many construction companies have implemented SM platforms to improve project team processes [

21,

22]. SM enables users to communicate and produce content without being physically present, as noted by Zhang et al. [

23]. SM platforms can assist organizations get around geographical restrictions by allowing team members to communicate constantly online. According to Aichner and Jacob [

24], SM can be classified into various categories, including social networking sites, blogs, forums, micro-blogs, photo and video sharing platforms, product/service review sites, evaluation communities, social gambling sites, and other online platforms. SM platforms named in the literature such as Slack, Twitter, WhatsApp, Facebook, YouTube, LinkedIn, WeChat, Wikipedia, Twitter, Instagram, TripAdvisor, online forums, ratings, and review forums are not only transforming the way people communicate everyday life but also opening up new chances for effective collaboration [

9,

10,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29].

Hasan et al. [

21] also argue that the use of SM has changed how knowledge is shared in construction projects due to their mobility. Despite the adoption of SM technologies by construction project teams, there is a lack of empirical research on the impact of SM use at work on construction project team processes and management performance, leading to uncertainty about the benefits of SM and reluctance to adopt them in the construction industry. Additionally, there is currently no effective framework to integrate these elements and provide a comprehensive explanation of how SM use affects team processes and performance. However, for SM use in construction projects to be fully beneficial, it must adhere to a set of standards [

15]. Some of the underlying principles that need to be looked at include a clear definition of the purpose and format of SM use, clarification of restricted and confidential project information, defining the roles and responsibilities of project team members, and establishing rules for differentiating between professional and private presence [

10]. One of the more confusing problems facing site teams today is finding ways to fairly and efficiently manage teams and team members while giving incentives to improve productivity and performance which could be achieved through effective team feedback [

30].

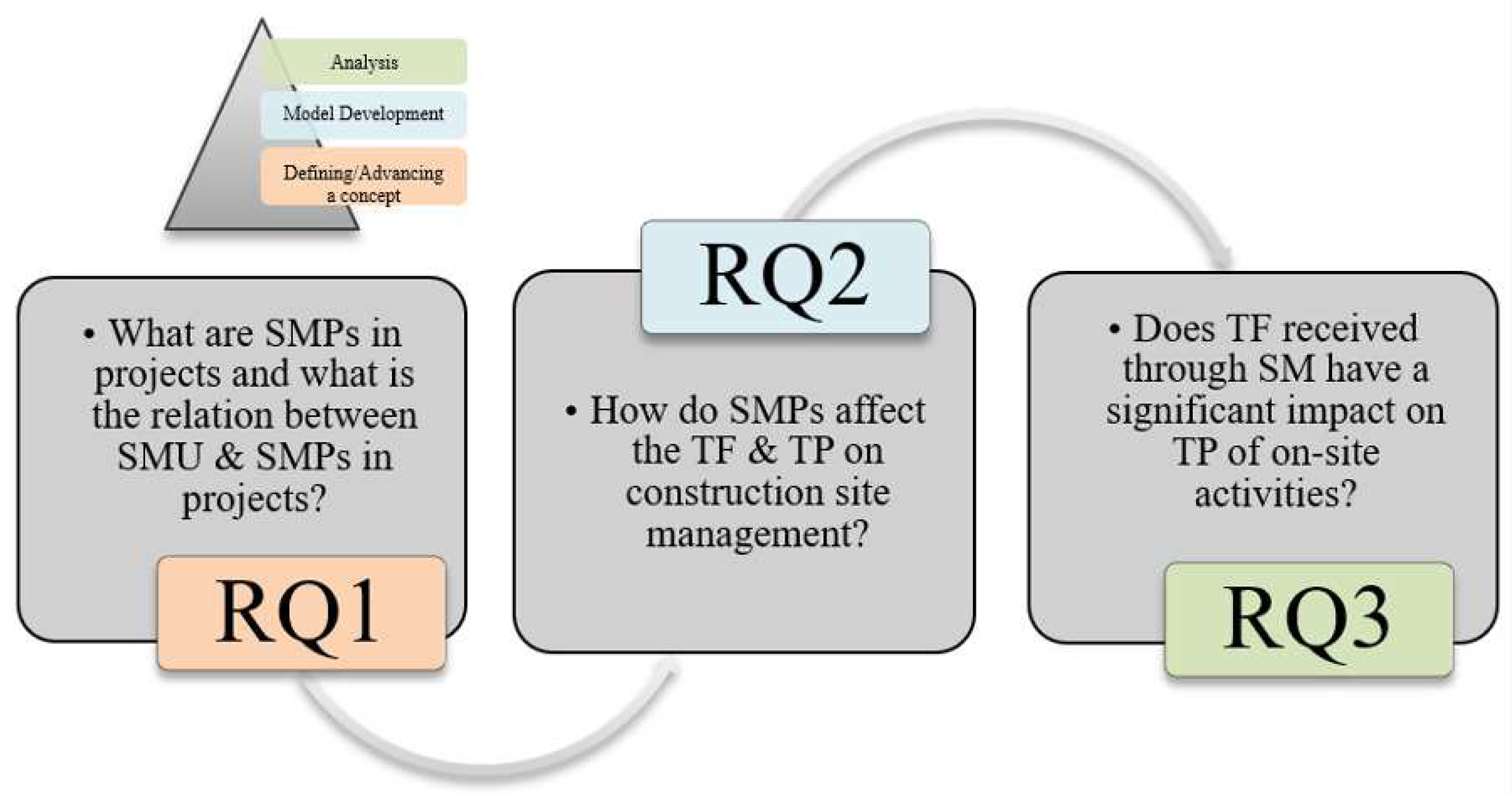

This research aims to investigate the impact of SM Practices (SMPs) on projects and project management, specifically in relation to team feedback and team performance. This study will use bibliometric and systematic review analysis to tackle the following research question.

Figure 1 shows the relationship between the research questions.

The answers to these questions will lead the reader and enrich their comprehension of the present progression of SMPs and their influence on projects and project management. The main contribution of knowledge for this research is understanding how SM changes team feedback and team performance in construction site management.

This paper is structured as follows. The next section outlines the Literature review. It is followed by the methodology section, then the discussion section that outlines the significance of the findings, in light of the existing literature including further research areas reviewed, and the final section, in conclusion, summarizes critical aspects of the study along with the limitations and future directions.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Social Media (SM) Definition

Social media (SM), as initially defined by Kaplan and Haenlein [

11], is a collection of Internet-based applications built on the technological and ideological foundations of Web 2.0, allowing for the creation and exchange of user-generated content. It encompasses a multisensory communication platform, enabling users to create, share, receive, and comment on social material among multiple users, thus differing from social networking, which is more direct and two-way in nature [

33]. Even though the phrases "social media" and "social networking" are frequently employed interchangeably and have some overlapping, they are not equivalent. SM operates as a communication platform that delivers a message, such as requesting something [44]. Kaplan and Haenlein [

11] mentioned that communication through social networking is two-way and direct, and information is shared among a variety of parties. Several ways can be employed to categorize SM, including collaborative projects (e.g., Wikipedia), content communities (e.g., YouTube), social networking sites (e.g., Facebook), and virtual games and worlds (e.g., World of Warcraft, Second Life). The importance of SM in communication and knowledge sharing [

10], the created perception of social presence/ intimacy [

11], real-time/ immediacy transparency are emphasized as a strong argument for organizations using it in projects.

In contrast, SM in construction projects offers a wider scope, incorporating tools like blogs, content communities, and social networking sites, as described by Kaplan and Haenlein [

11]. Its applications are varied, including enhancing communication within the supply chain and supporting collaboration, especially in projects with teams spread across different locations. For instance, Kaplan [

33] discussed how mobile social media can be leveraged for marketing research and relationship development in construction projects. Here, the focus is broader, extending communication beyond the internal team to include public and external stakeholders. SM serves as a platform for real-time interaction, facilitating a more inclusive and participatory approach in construction processes, as illustrated by the use of social media for stakeholder engagement in international projects [

34]. This expansive approach to communication harnesses the potential of SM to reach and engage a wide array of participants, from team members to the general public.

2.2. Using SM in Project Teams

SM serves as a potent platform for social networking, offering a range of information and communication tools that facilitate multiple communication channels in both social and work settings [

45]. Despite extensive research on the individual and organizational impacts of SM use [

46,

47], its effects at the project level, particularly in the construction sector, are less understood, warranting further exploration [

48]. Recent studies have begun to reveal the benefits of SM use in construction organizations, such as enhanced knowledge accessibility, reduced costs, and improved customer relations [

49]. Facebook, LinkedIn, and Twitter have been identified as popular SM platforms among construction professionals [

22], while in China, platforms like WeChat and DingTalk are gaining prominence in various industries, including construction [

25]. Azhar and Abeln [

50] noted the advantages of SM platforms in increasing communication effectiveness in the construction industry, while Hasan et al. [

51] argued that SM technologies contribute to increased construction productivity through improved communication and knowledge sharing.

SM offers a flexible platform for various forms of collaboration in the workplace, ranging from simple task coordination to complex collaborative efforts [

52]. It allows for active involvement through collaboration embedded within informal social interactions, fostering a shared vision among group members and aligning goals. The use of SM enhances collaboration, communication, and teamwork in work environments. Cao et al. [

53] indicated that SM usage significantly contributes to the development of employees’ social capital, as evidenced by the formation of network links, shared vision, and trust, which facilitate knowledge transfer within organizations. This, in turn, positively impacts work performance.

Furthermore, Cummings [

54] suggested that the positive correlation between knowledge sharing and team performance is bolstered by network diversity. SM platforms are categorized into work-oriented types like Microsoft Yammer and Slack, and socialization-oriented types such as task management tools and internal corporate communication platforms, acknowledging the dual nature of SM use in addressing both work-related and social needs of employees [

25]. The synergy between these categories enhances team and employee performance, where work-oriented SM platforms offer tangible benefits like efficient communication and job monitoring, while socialization-oriented platforms contribute to effective relationships and trust, crucial for team performance [

55].

2.3. SM and Knowledge Sharing in Project Management

Knowledge sharing in project management, particularly within the context of SM, is an evolving area that has garnered considerable attention in recent years. Ma et al. [

9], Dong et al. [

56] define knowledge sharing as the effective communication of knowledge from a source to a recipient, fostering learning and application of that knowledge. SM platforms, as described by Leonardi [

57], serve as "

leaky pipes" for communication, enhancing the accuracy of members’ metaknowledge—awareness of who knows what and whom. This facilitates knowledge sharing in a community where members engage in public communication.

Trust is identified as a critical prerequisite for effective knowledge sharing [

58]. Studies by Cramton et al. [

59] and Ma et al. [

9] suggest that visibility in communication plays a crucial role in building interpersonal trust, which is essential for knowledge sharing. Neeley and Leonardi [

60] emphasize the importance of informal interactions within organizations for fostering this trust. They found that employees’ use of SM for both non-work and work-related content aids in acquiring necessary knowledge while developing a sufficient level of trust for knowledge sharing. Song et al. [

25] further illustrate that SM platforms oriented towards socialization are particularly effective in facilitating team knowledge sharing. In the construction project context, Ma et al. [

61] note that the use of SM enhances visibility and informal interactions, thereby fostering trust among project teams and promoting knowledge sharing.

Furthermore, knowledge sharing on SM platforms has been recognized as a crucial tool for large groups to connect and exchange knowledge [

11,

62]. Organizations are increasingly encouraging the use of SM for knowledge sharing, as it enables efficient information flow within and between teams [

63]. Ahmed et al. [

64] identified three distinct activities that enhance the benefits of SM for knowledge sharing: knowledge-seeking, knowledge-contributing, and social interactivity.

In terms of measuring knowledge sharing in virtual teams, two theories are prominent: The Social Exchange Theory and the Knowledge-Based Theory [

6,65]. According to the Knowledge-Based Theory, each team member is a potential source of knowledge, and virtual teams built on SM can share information more effectively due to faster dissemination and a smaller internal feedback loop. The Social Exchange Theory, on the other hand, posits that individuals act to maximize reward with minimal effort. While SM facilitates rapid information sharing, it may also lead to delays in project completion if team members are hesitant to share knowledge due to the extra effort required to interpret ambiguous information [66]. These studies collectively highlight the transformative role of SM in knowledge sharing within project management, emphasizing the importance of trust, visibility, and informal interactions in promoting effective knowledge exchange.

Table 1 provides a summary of the main challenges faced when using SM for knowledge sharing [

64].

2.4. SM and Coordination in Project Management

SM has become an increasingly significant tool for coordination in project management. According to Briscoe and Rogan [

70], coordination is essential in integrating different components within an organization, especially in complex projects like construction. SM platforms offer a new avenue for both individual and group interactions, streamlining coordination and enabling the creation of chat groups for efficient communication [

71]. These platforms are especially beneficial in construction projects where tasks are often interdependent and delegated to individuals [

20]. Online communities formed by project members on these platforms facilitate the sharing of work structures, goals, schedules, rules, and procedures, contributing to a shared understanding of the project [

72,

73]. Yu et al. [

74] point out that such online communities also help mitigate information and communication overload, thereby enhancing team coordination efficiency.

Research indicates that while SM use at work impacts coordination, its effect is somewhat weaker compared to communication and knowledge sharing [

61]. However, SM remains a new-generation collaboration tool that aligns tools, tasks, and teams, thereby facilitating team coordination [

52]. Majchrzak et al. [

75] highlight the importance of met voicing and triggered attending in facilitating interactions essential for coordination. Imran et al. [

76] found that SM contributes to relationship building, trust, coordination, and cohesion in project management. Moreover, Juarez-Ramirez et al. [

77] demonstrated that platforms like Facebook and G+ motivate team members, particularly younger developers, to remain online, thus aiding in communication and coordination in software projects.

In summary, SM platforms have emerged as powerful tools for enhancing team coordination in project management, particularly in complex and geographically dispersed projects. They facilitate efficient communication, foster shared understanding, and support relationship building, which are key elements for successful project coordination.

2.5. SM and Communication in Projects

Effective communication is fundamental to project management, impacting various stages and aspects of project teamwork. In the initial stages of a project, effective communication aids in establishing clear objectives and strategies as described by Mathieu and Schulze [

78]. As projects progress, communication becomes vital during action episodes, defined by Marks et al. [

79] as periods of active task engagement by team members.

Research underscores the importance of communication in facilitating essential team processes that drive performance. These processes include monitoring progress, systems monitoring, team monitoring, backup behavior, and coordination [

79,

80]. Effective communication is the most influential attribute in enhancing team performance [

81], fostering trust, cohesion, and improved performance, especially in virtual teams [

82]. Moreover, Salvation [

83] notes that effective communication in project teams enables goal achievement and reduces workplace conflicts.

However, challenges arise during action episodes due to distributed attention and multitasking [

84], which can lead to slow response times and progress delays [

85]. Despite these challenges, the utilization of SM platforms has been shown to significantly improve communication among project team members. SM platforms support real-time information exchange and are increasingly essential in various industries, including marketing, healthcare, and IT [

12]. They facilitate continuous communication, even after task assignments, and enable instant feedback and two-way communication [

13]. Teams utilizing SM platforms tend to achieve better outcomes with less effort, highlighting the platform’s potential in project management [

84]. Project managers can leverage these platforms for both formal and informal communication, aiding in coordination and status understanding [

86]. In addition, the use of SM platforms contributes to improved team synergy, enhanced trust, faster communication, cost savings, and improved response times as stated by Kanagarajoo et al. [

10].

Hence, effective communication is a critical component of successful project management, significantly impacting team performance across various stages and activities. The integration of SM platforms further enhances this impact, facilitating real-time, efficient communication and collaboration within project teams.

2.6. Feedback in Team

Feedback is described as the sharing of information about actions, events, processes, or behaviors related to task completion or teamwork to team members or the entire team [

95,

96,

97,

98]. Giving teams feedback has been promoted as a significant strategy for enhancing their performance and ability to learn [

98]. A study also demonstrated that performance and occasionally a wide range of crucial team processes and states (such as motivation, team goals, collaboration, and cohesion) may be influenced by feedback as well as on occasion performance [

99].

Feedback is vital for enhancing individual and team performance in various contexts, including construction projects. It is a dynamic two-way process involving both the sender(s) and receiver(s) [

87]. Feedback actions, defined as information provided by an external source about specific aspects of an individual’s task performance as stated by Kluger & Denisi [

88], enable individuals to adapt and refine their efforts. This information can relate to both successful and unsuccessful actions, shaping specific social roles in pursuit of goals [

89]. In the construction industry, feedback has numerous applications. For instance, user feedback from multifamily housing projects has led to suggested construction details to satisfy users’ privacy needs [

90]. Additionally, technologies like 4D CAD and linear scheduling offer clear, multi-dimensional feedback to project teams, aiding in the identification of effective construction strategies [

91,

92]. In multidisciplinary design teams, individualized peer feedback, where students select performance competencies and cite specific behavioral examples, has proven effective [

93]. Geotechnical monitoring in tunnelling projects serves as a technical quality element in the feedback control system [

94].

Effective teamwork relies on feedback [

98,

100]. Teams learn from feedback when members share information, add meaning to assertions, build understanding, and constructively discuss disagreements [

101,

102]. Feedback in the workplace serves several positive purposes, such as directing behavior, influencing performance goals, educating employees on their strengths and areas for improvement, and providing reinforcement. However, some individuals may react negatively to feedback due to evaluation anxiety and concerns about others’ responses [

103].

2.6.1. Team Feedback on Construction Site

Team feedback is essential in construction site management for regulating activities and team processes. Traditionally, managers relied on personal experience and peer advice for task interpretation and completion [

104]. However, the industry has evolved to recognize the importance of more structured feedback mechanisms. Goal setting and feedback methods significantly improve safety performance on construction sites, with commitment to safety being crucial for success [

105,

106]. Feedback reduces risk-taking among contractors, thereby improving occupational health and safety performance [

107]. Dialogue-based feedback enhances team understanding and acceptance of change, leading to improved performance and change acceptance [

108].

The introduction of SM technology in the construction industry facilitates instant information sharing, timely updates, and immediate input among team members [

109]. SM platforms are valuable channels for sharing solutions, feedback, and opinions, fostering knowledge exchange and collaboration within the construction community [

64]. Additionally, a leading-indicator-based safety communication and recognition program in construction increased site unity and team-building, highlighting the importance of engaging all workers through reliable and consistent communication infrastructure [

110]. Enhanced communication, feedback, education, and regular observation can improve behavioral safety awareness among construction workers [

111].

In summary, structured feedback mechanisms, supported by goal-setting, dialogue-based approaches, and modern communication technologies like SM, have become integral to improving safety, performance, and collaboration in construction site management. This evolution from reliance on individual experiences to structured, team-based feedback represents a significant advancement in the construction industry.

2.7. SM and Team performance

Team performance in the construction industry, an "information-dependent" sector, is crucial for organizational success. Effective communication is vital for ensuring seamless collaboration and quality project delivery [

112]. The industry has recognized the need for alternative communication methods, as challenges in communication can lead to increased expenses and impact project quality [

113]. SM has emerged as a powerful tool in this realm. It enhances information management and overall project performance by improving information sharing, accessibility, and knowledge exchange [

114,

115,

116,

117]. Recent studies have shown that the social network model in construction fosters professional trust and strong communication, leading to high-performance teams [

118]. SM’s positive impact on project management includes time reduction [

119] and its significant role in improving small and medium-sized enterprises’ business performance by increasing knowledge accessibility and reducing costs [

49].

Moreover, SM use at work positively influences knowledge acquisition, enhancing construction managers’ work performance [

13]. Both work-oriented and socialization-oriented SM use promote knowledge acquisition and project social capital, benefiting project performance [

48]. However, it’s important to note that while SM facilitates collaboration and information sharing, team cohesion and trust dynamics are significant factors in its effectiveness [

120]. In summary, effective knowledge sharing, information flow, and contributions are essential for success in the construction industry, and SM platforms are increasingly recognized as facilitators of these processes. They offer new ways of communication and collaboration, enhancing team performance and project management in construction [

121].

3. Methodology

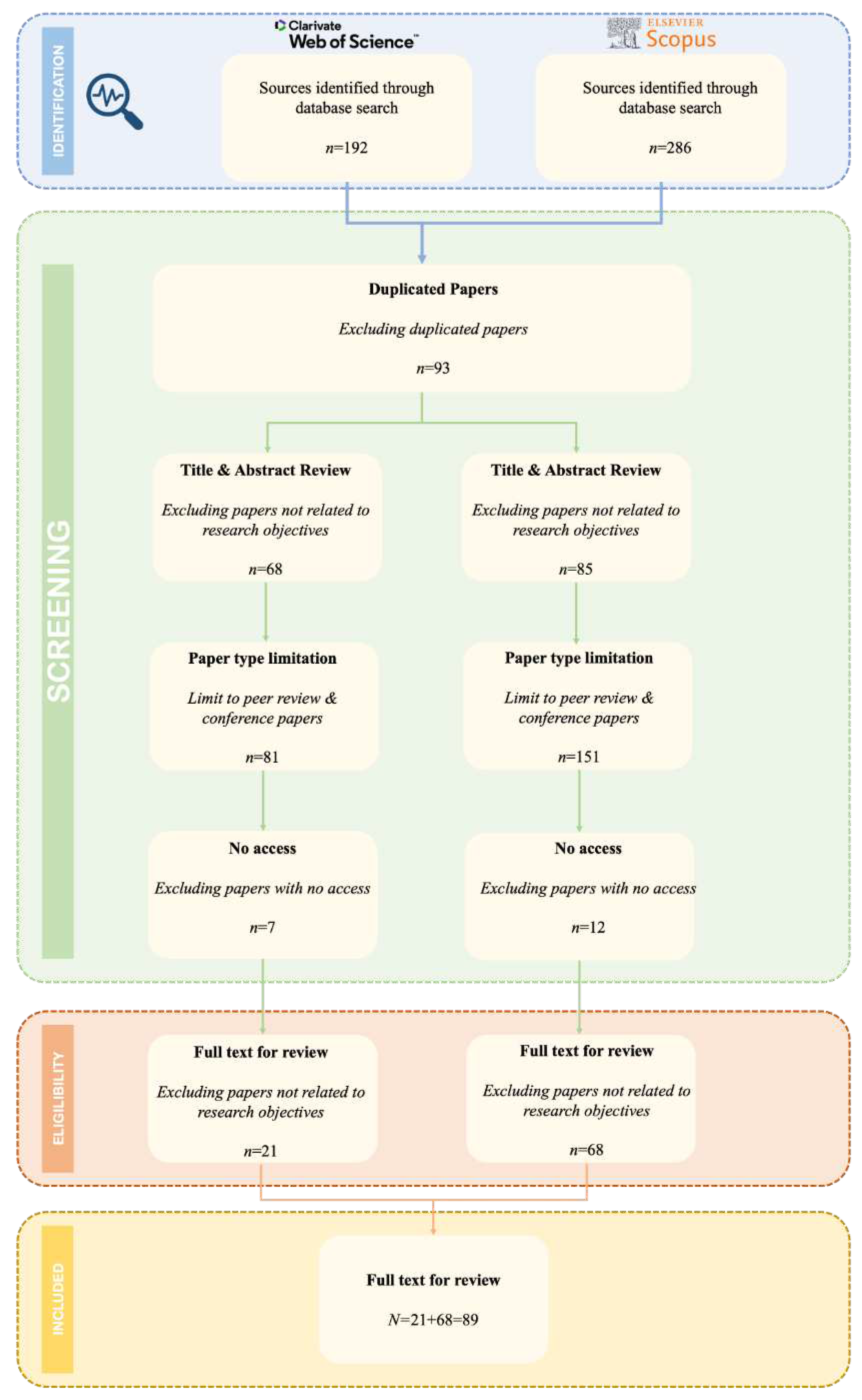

In the context of this research, a Systematic Literature Review (SLR) was conducted with a focus on exploring the interplay between Social Media (SM) use, Team Feedback, Team Performance, and Construction Site Projects. In July 2023, the SLR process commenced with a comprehensive collection of scholarly papers. A substantial data-set of 478 papers, including journal articles and book chapters, was initially gathered from renowned databases like Scopus and Web of Science (WoS). These sources served as primary data repositories for the study.

To refine this extensive collection, an exclusion criterion was applied. Papers that were not directly related to construction projects or SM use, as well as those not written in English, were excluded from the data-set. This rigorous screening resulted in a distilled selection of 89 papers, which were then subjected to a detailed bibliometric and systematic review analysis.

The methodology underpinning this SLR adhered to the PRISMA protocol, ensuring a structured and systematic approach. The PRISMA protocol is primarily intended to guide the development of systematic review protocols and meta-analyses evaluating therapeutic efficacy. However, even for reviews that do not assess efficacy, authors are encouraged to utilize PRISMA due to the lack of existing protocol guidance. This protocol serves as a valuable resource for authors preparing systematic review protocols for publication, public consumption, or other purposes. It is also useful for individuals commissioning and potentially funding reviews, providing guidance to applicants on what should be included in their review protocols, and aiding peer reviewers in assessing the completeness of a protocol [

37].

The original PRISMA 2009 statement comprised 27 checklist items that represented a minimum set of information required to convey in a systematic review report. These checklist items covered various aspects such as the rationale for the review, databases used for study identification, results of conducted meta-analyses, and implications of the review findings. Each checklist item was accompanied by an "explanation and elaboration" section, providing rationale and additional guidance, along with exemplars to facilitate comprehensive reporting. The approach employed in this review aims to elucidate the relationships among authors, regions, keywords, and journal citations, while also providing a concise evaluation of the current state-of-the-art research fields and potential emerging trends [

39].

The process unfolded in five key stages [

35,

36]:

Conducting a Bibliometric Analysis: This step involved a comprehensive examination of the selected literature, assessing aspects such as publication trends, thematic concentrations, and authorship patterns.

To facilitate the search and selection of relevant literature, keyword searches were employed. The research utilized a specific keyword group:

("Social media use" OR "Social media") AND ("Project management" OR "Construction site" OR "Team feedback" OR "Team performance"). This targeted search strategy ensured the identification of literature that specifically addressed the intersection of these critical areas.

Figure 2.

Methodology of the current research.

Figure 2.

Methodology of the current research.

4. Results & Discussion

This paper is based on an intensive literature review, providing an overview of the impact of SM practices on projects and project management, specifically in relation to team feedback and team performance. The present study uses a systematic literature review of the scientific research related to SM in the construction industry during the research time-frame from 2004 to 2022.

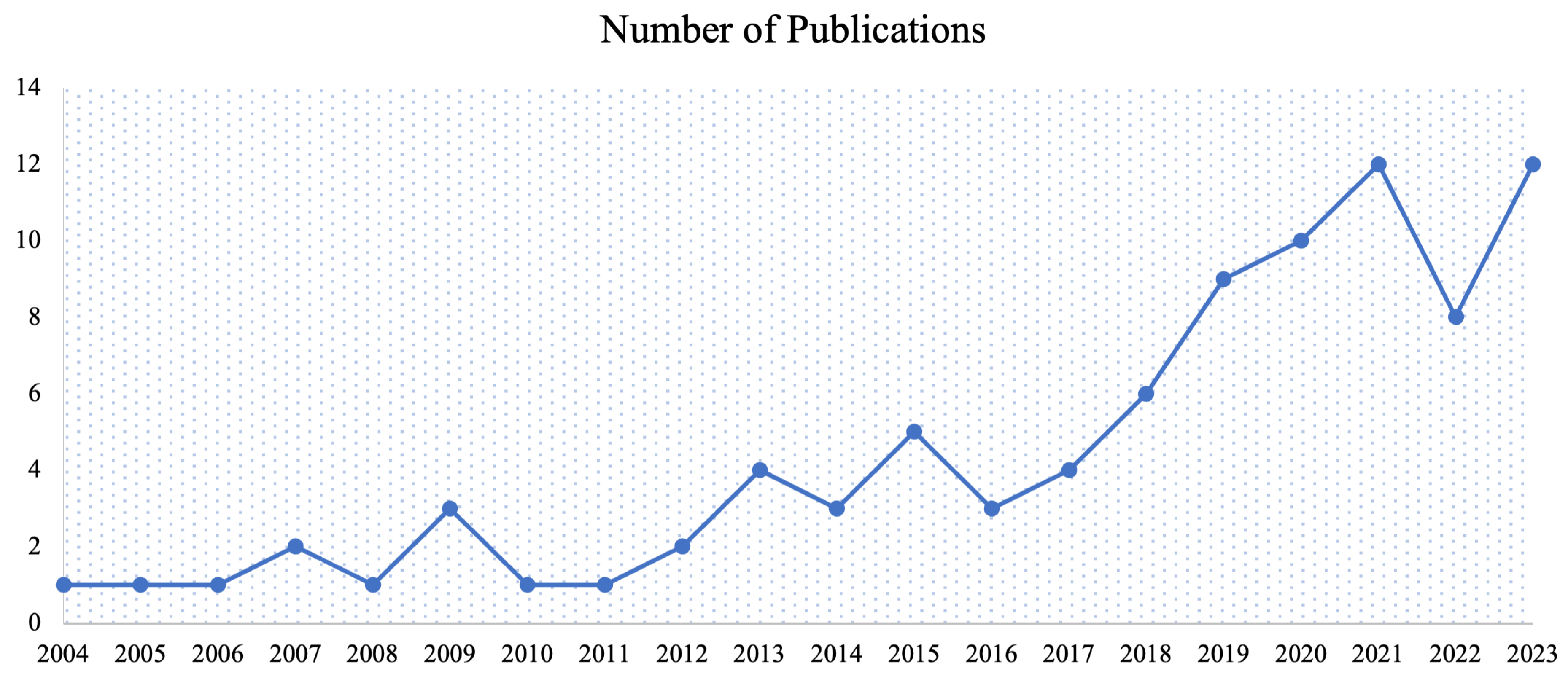

As shown in

Figure 3, the number of papers published on "The Impact of Social Media Use on Team Feedback and Team Performance on Construction Projects" showed intermittent growth over the years. The data starts with a consistent number of one publication per year from 2004 to 2006, after which there is a gradual increase, with a notable jump to three publications in 2009. The growth continues with minor fluctuations, reaching a peak of 12 publications in both 2021 and 2023. The year 2020 also stands out with a significant rise to 10 publications. The overall trend indicates a substantial growth in research output over the two decades, with an increase of 1100% from the starting point.

The noticeable increase in research publications on the use of social media in construction project management reflects the growing use of these platforms in work environments. As social media becomes a key tool for gathering knowledge and building valuable relationships and resources within projects, its impact on the way teams manage projects and work together becomes more significant. This recognition of social media’s role is supported by studies like those of Ma et al. [

3], which point out its vital function in overseeing construction projects. Additionally, social media’s ability to aid in communication, collaboration, and information management is crucial for improving work efficiency and helping employees grow, as seen in the findings of Hysa and Spalek [

15].

Moreover, the beneficial influence of social media on job performance, as investigated by Jia et al. [

13], suggests that its workplace use significantly leads to better management practices. The ability of social media to enhance a team’s creativity and innovation is highlighted in the research by Ali et al. [

40], indicating its potential to encourage new and imaginative solutions within teams. Furthermore, the role of social media in making project management more time-efficient is an area of active study, offering practical advantages that have caught academic interest, as noted by Al-Shehan and Assbeihat [

41]. The idea of construction projects as social networks, which promote trust and effective communication, leading to successful project teams, has also been explored in literature, particularly in the work by Chinowsky et al. [

42], showing the strategic importance of social media. Lastly, the changing research interests, including studies on trust in online teams and sharing expertise, show the changing role of social media in construction project management, as illustrated by Kaur et al. [

43].

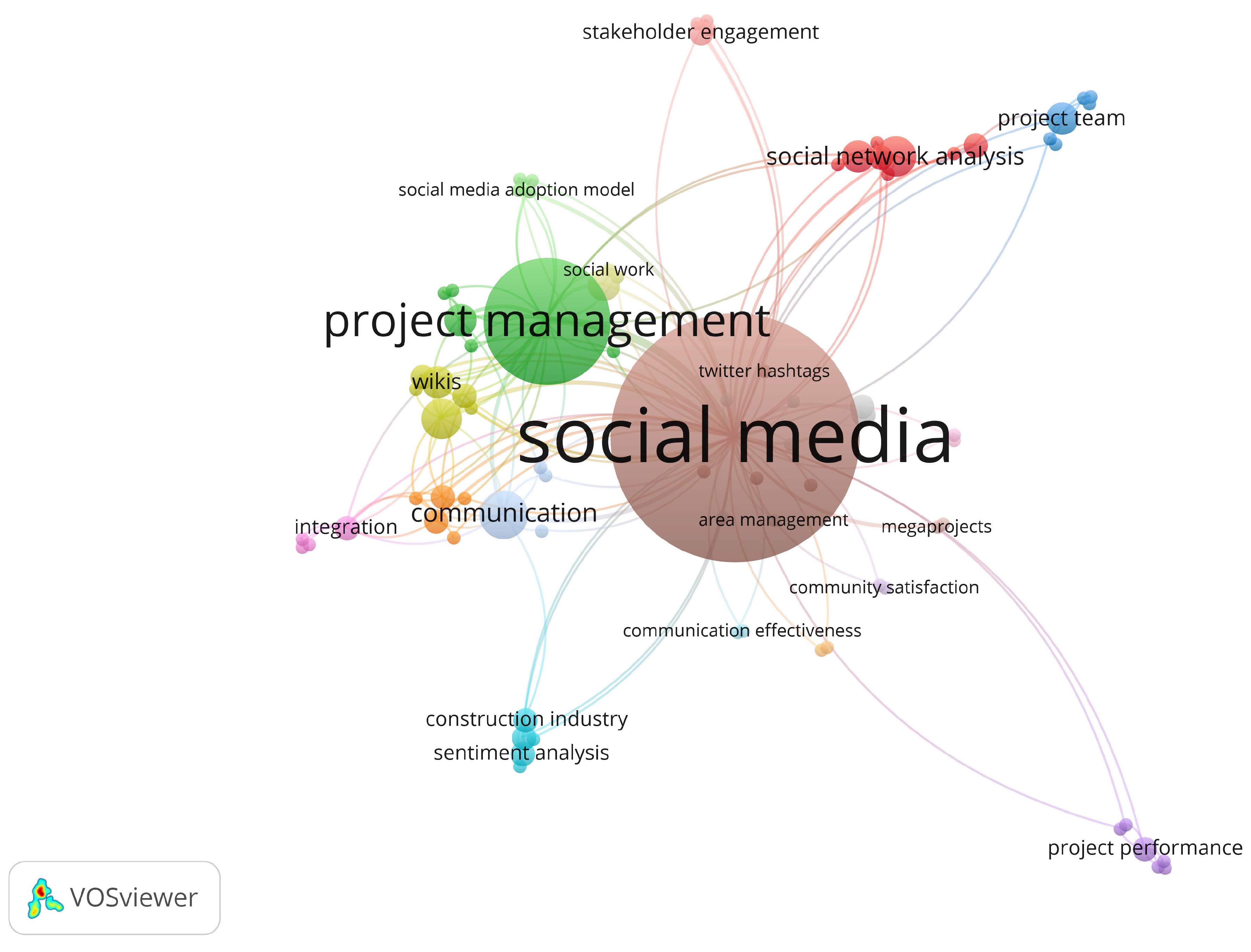

Figure 4 presents a keyword network analysis from VOSviewer, which illustrates the key terms related to the research on the influence of social media on team communication and performance in construction projects. The central focus of the network is ’social media,’ which is the largest node, indicating its significant role in the research area. This key term is strongly linked to ’team management’ and ’team performance,’ suggesting these are the main areas of interest when examining the effects of social media within the field.

Surrounding these core terms are other related keywords, such as ’wikis,’ ’twitter hashtags,’ ’feedback,’ and ’area management.’ Each of these is connected to the central node, showing their relevance to the research topic. The different colors in the network represent various themes or clusters, indicating that the research covers multiple facets of managing construction projects. The thickness of the lines between terms signifies the strength of the relationship between them, with thicker lines showing stronger connections. This visualization helps to understand the discussion around the use of social media platforms like Twitter in improving team dynamics and the management of construction projects, as evidenced by terms like ’twitter hashtags’ and ’area management.’

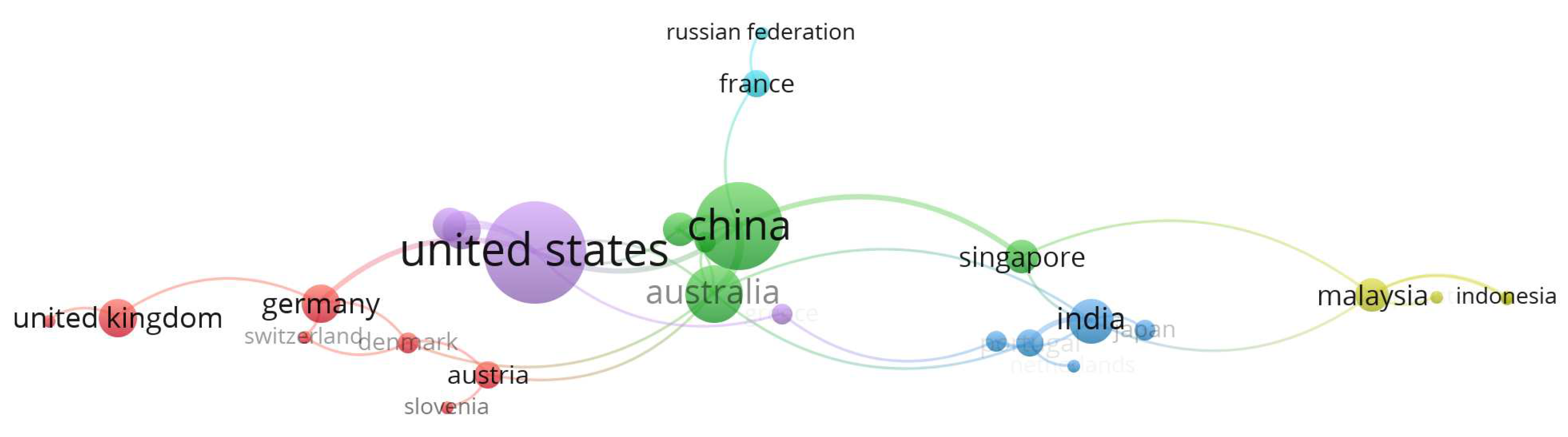

Figure 5 shows a network map of countries based on their research output on the impact of social media use on team feedback and team performance on construction projects. The size of the nodes represents the number of publications from each country, and the edges between nodes represent co-authorship between countries.

The figure shows that China, the United States, and Australia are the most active countries in this field of research. China has the largest number of publications, followed by the United States and Singapore. These countries are also well-connected to other countries in the network, suggesting that they are playing a leading role in international collaboration on this topic. Other countries that are active in this field of research include France, Norway, Slovenia, Australia, Malaysia, India, Germany, and Lithuania. These countries are less well-connected to other countries in the network, suggesting that they are doing more research on this topic independently. The figure also shows some interesting relationships between countries. For example, China and Singapore are well-connected, suggesting that there is a strong collaboration between these two countries on this topic. China is also well-connected to the United States, suggesting that there is some collaboration between these two countries as well. However, the United States is not as well-connected to other countries in the network, suggesting that it is doing more research on this topic independently.

4.1. What are SMPs in projects and what is the relation between social media use (SMU) and SMPs in projects? (RQ1)

Social Media Practices (SMPs) in projects encompass the strategic use of social media platforms to achieve specific objectives like communication, collaboration, knowledge sharing, and stakeholder engagement. The interplay between Social Media Use (SMU) and SMPs significantly impacts project performance and team dynamics. Platforms such as Slack enable real-time communication and collaboration, essential for effective project management [

10,

26,

29,

122]. The immediacy of social media benefits project managers in maintaining touch with team members and coordinating communication [

12].

The adoption of SM in organizations is facilitated by leadership that fosters a knowledge-sharing culture aligned with business needs [

123]. Social media platforms, including Twitter and Facebook, serve as tools for corporate communication, knowledge sharing, and engaging external stakeholders, thus enhancing project collaboration [

124,

125]. Recent research indicates that social media fosters workplace learning in globally dispersed project environments, contributing to virtual collaboration and socialization, and plays a significant role in building relationships, trust, coordination, and cohesion in project management [

76].

Moreover, social media strategies in large projects, such as organizational promotion and community engagement, are vital for stakeholder management and brand advocacy [

133]. However, SM can also lead to challenges such as distrust and division among managers and communities [

134]. Ultimately, strategic SMU and SMPs contribute to project success and efficient management, offering a balanced approach to knowledge sharing, social engagement, and collaboration [

41].

Quantitative studies reveal varied impacts of SMU and SMPs on project management and team performance. Facebook use at work negatively correlates with project success, while LinkedIn and other platforms positively influence project outcomes [

135]. Social media collaboration in software project management enhances team performance, trust, and cohesion [

76]. While social media use in project management poses challenges like behavioral and cognitive issues [

16], it also offers opportunities for enhanced communication, knowledge management, and productivity [

15]. Organizational use of social media positively impacts business outcomes and customer satisfaction, influenced by various factors [

136]. However, the lack of a strategic approach often limits the effectiveness of social media in project management [

14,

137].

In conclusion, the relationship between SMU and SMPs in project management is multifaceted. Social media platforms can significantly enhance project success and team dynamics, but their effectiveness depends on strategic alignment with project goals and managing potential risks. Understanding and leveraging this relationship is key to maximizing the benefits of social media in project management.

4.2. How do SMPs affect team feedback (TF) and team performance (TP) on construction site management? (RQ2)

Social media practices (SMP) in construction site management have a multifaceted impact on team performance, communication, and feedback dynamics. The utilization of SM, such as Twitter, has been identified as a useful tool for enhancing communication, education, and positive feedback within teams. This results in improved team performance and engagement [

126]. Furthermore, the social network model of construction strengthens professional trust and robust communications, thereby leading to the formation of high-performance project teams [

127]. Social media networks also contribute to improving project team dynamics and ensuring greater user involvement, senior management commitment, and meeting user/system requirements [

128]. Notably, SM in community of practice-based discussion groups positively affects organizational performance through embedded information and social communication, which is crucial in construction management [

129]. Moreover, SMP in construction management have been found to positively impact project management, especially in reducing time and enhancing efficiency [

119]. These platforms are generally trusted by employees, facilitating effective employee engagement and collaboration activities, which are critical in the dynamic environment of construction sites [

130].

The technologies behind social media enable behaviors like visibility, persistence, editability, and association, influencing socialization, knowledge sharing, and power processes in organizations [

72]. This increase in transparency and inclusiveness in organizational strategizing leads to the development of new internal capabilities to appropriately structure feedback [

131]. SM also facilitates improved communication among team members, leading to increased productivity and better quality outcomes [

132]. Collaborative tools like Skype, NetMeeting, and Twitter support development initiatives and information sharing, enhancing team and employee performance through a synergy between work-oriented and socialization-oriented social media [

138]. Trust among virtual project team members in the construction sector is significantly affected by social media interactions, and the use of social media in community of practice-based discussion groups positively affects organizational performance through embedded information and social communication [

43].

Regarding team feedback, SM plays a critical role. Feedback and guided reflexivity supported by social media can lead to performance change at the beginning of team activity, influencing motivation, team goals, collaboration, and cohesion [

99]. SM initiatives impact internal efficiency, team collaboration, innovation, organizational alignment, and cultural transformation, with platforms like Twitter having a more powerful influence over Facebook in enhancing business performance [

139]. This demonstrates how social media practices in construction site management are vital for enhancing team communication, trust, innovation, knowledge sharing, and performance, though the effects of these practices can be complex and context-dependent.

4.3. Does team feedback (TF) received through SM have a significant impact on team performance (TP) of on-site activities? (RQ3)

SM has become a critical tool in the construction industry, influencing various aspects of team performance and feedback mechanisms. Research shows that the use of social media at work positively impacts knowledge acquisition, task self-efficacy, and creativity, leading to improved performance among construction managers. This enhancement in work performance is attributed to better communication, heightened synergy among team members, and increased trust and teamwork fostered through social media platforms [

13].

The construction industry, involving a wide range of stakeholders including clients, users, designers, contractors, and suppliers, benefits significantly from the strong communication and professional trust that social media fosters within project teams. The social network model in construction, for example, has been shown to lead to high-performance outcomes in engineering companies by enhancing this trust and communication [

42]. However, it’s important to balance the collaborative advantages of social media with the need for individual autonomy. Excessive collaboration and interdependency might negatively impact team performance, underscoring the need for a balanced approach to social media use in team dynamics [

140].

The role of social media in external stakeholder engagement within construction projects has expanded significantly, proving especially effective in government and large-scale projects. These platforms serve as powerful tools for communicating project progress, engaging with community members, and promoting organizational goals. For example, Information and Communication Technology (ICT) practices, including social media, are strategically used in mega-projects to persuade and frame stakeholder perspectives, emphasizing their critical role in project success [

133]. Social network analysis in construction project management research reveals the increasing relevance of social media in managing both internal and external stakeholder networks, which are key to project success [

141]. Furthermore, social media bridges communication gaps in urban planning and building projects, enhancing citizen participation and improving stakeholder engagement [

142]. External social media platforms like WeChat have been instrumental in re-configuring collaboration practices in e-government projects, promoting more flexible time management, task creation, and team engagement, which is particularly relevant for complex construction projects [

143]. Additionally, a case study on UK’s Crossrail 2 mega-project demonstrates how social media influences decision-making and stakeholder strategies, proving its effectiveness in large-scale infrastructure projects [

144].

The impact of social media on knowledge production and team innovation performance is particularly notable. When teams use social media effectively for tasks and technology, it positively impacts the knowledge production process, leading to enhanced innovation performance. This effect is amplified when team members are mature in their use of social media for both tasks and technology mediums [

84]. Moreover, the way a team provides feedback through social media is crucial; effective feedback mechanisms significantly influence individual members’ perceptions of team performance and their motivation to contribute, thereby aligning team goals and efforts [

145,

146].

5. Conclusions & Future Directions

The impacts of SM platforms on communication within a team will depend on how they are used and the context in which they are used. By using SM platforms strategically and effectively, teams can enhance communication, collaboration, and engagement, while minimizing potential distractions and security concerns.

Using SM for project management is currently a relatively unexplored area that receives limited attention from researchers, according to existing studies, however, some discoveries in the parallel literature give insights into potential new dynamics that need to be explored in projects. The definitions of SM are still evolving and may refer in similar contexts to different applications, uses, and expectations. Using SM in projects can be attributed to communication, profile building, knowledge sharing, the perception of social presence/ intimacy, real-time/immediacy, and providing cultural context to the relationship, which is emphasized as potential avenues for improved collaboration. The associated benefits are 1) Professional profile and relationship building (e.g., trusted followers), 2) greater social presence and interactions with other team members, 3) accessibility to information, increased interactions with others, and 4) immediate available, shared, and personalized information. The limitations mentioned included 1) behavioral (a "write first, think later" tendency; a lack of focus and direction in discussions); 2) cognitive (impaired decision-making due to a lack of appropriate and complete information); and 3) environmental (management of access control and accountabilities; information leakage) limitations 4) lack of trustworthiness 5) confidentiality/ privacy 6) the leakage of sensitive key project data 7) the lack of clarity of ownership of technical infrastructure 8) inclusive SM rules 9) software breakdown problems 10) resistance from older staff members, and 11) data synchronization problems.

This study has several limitations. First, the systematic literature review identifies current trends in the field and provides propositions for future research, yet the review does not empirically examine the propositions, which is the next logical step. Second, although we have used two large databases with a significant number of indexed contents, we have limited our search to Scopus and Web of Science (WOS). This means our final included body of knowledge could have omitted relevant articles. The third limitation is that we limited our search based on a pre-defined set of inclusion-exclusion criteria. This means our final included body of knowledge has excluded book chapters, conference proceedings, non-peer-reviewed articles, and non-English articles. However, our methodological rigor and use of alternate keywords with search in the title and abstract, we believe would have reduced the chances of an omitted paper bearing critical implications for our analysis and interpretation of the findings. Up to this point, the phenomena of social media’s impact on projects have been constrained to a restricted utilization of theories, namely stakeholder management theory, social capital theory, social exchange theory, and knowledge-based theory.

In order to enhance the discussion and understanding of social media, there is a need for empirical study of the practice of social media use. Future research on social media in project management needs to investigate practices around social media in real-world projects and how those impact the management of projects.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.K. and R.C.M.; methodology, R.K.and M.B.S.; software, M.B.S.; validation, R.C.M. and Y.F.; formal analysis, R.K.; investigation, R.K.and M.B.S.; resources, R.K.and M.B.S.; data curation, R.K.; writing—original draft preparation, R.K.and M.B.S.; writing—review and editing, R.C.M. and Y.F.; visualization, R.K.and M.B.S.; supervision, R.C.M.; project administration, R.C.M.; funding acquisition, R.C.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SM |

Social Media |

| SMU |

Social Media Use |

| SMP |

Social Media Practice |

| TF |

Team Feedback |

| TP |

Team Performance |

| WoS |

Web of Science |

| PRISMA |

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| SNA |

Social Network Analysis |

| SLR |

Systematic Literature Review |

References

- Guofeng, M.; Jianyao, J.; Shan, J.; Zhijiang, W. Incentives and contract design for knowledge sharing in construction joint ventures. Automation in Construction 2020, 119, 103343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.-S. Information literacy, creativity and work performance. Information Development 2019, 35, 676–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Jiang, S.; Wang, D. Understanding the effects of social media use on construction project performance: a project manager’s perspective. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management 2021, 29, 551–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattineni, A.; Schmidt, T. Implementation of mobile devices on jobsites in the construction industry. Procedia Engineering 2015, 123, 488–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsharo, M.; Gregg, D.; Ramirez, R. Virtual team effectiveness: The role of knowledge sharing and trust. Information & Management 2017, 54, 479–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wei, S. The impact of social media use for communication and social exchange relationship on employee performance. Journal of Knowledge Management 2020, 24, 1289–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molm, L. D.; Takahashi, N.; Peterson, G. Risk and trust in social exchange: An experimental test of a classical proposition. American Journal of Sociology 2000, 105, 1396–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nah, S.; Saxton, G. D. Modeling the adoption and use of social media by nonprofit organizations. New Media & Society 2013, 15, 294–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Jia, J.; Ding, J.; Wu, M.; Wang, D. Examining the impact of social media use on project management performance: Evidence from construction projects in China. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 2021, 147, 04021004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanagarajoo, M. V.; Fulford, R.; Standing, C. The contribution of social media to project management. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management 2019, 69, 834–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, A. M.; Haenlein, M. Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social Media. Business Horizons 2010, 53, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W. Y. C.; Pauleen, D. J.; Zhang, T. How social media applications affect B2B communication and improve business performance in SMEs. Industrial Marketing Management 2016, 54, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Ma, G.; Jiang, S.; Wu, M.; Wu, Z. Influence of social media use at work on construction managers’ work performance: the knowledge seeker’s perspective. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management 2021, 28, 3216–3235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daemi, A.; Chugh, R.; Kanagarajoo, M. V. Social media in project management: A systematic narrative literature review. International Journal of Information Systems and Project Management 2021, 8, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hysa, B.; Spalek, S. Opportunities and threats presented by social media in project management. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ram, J.; Titarenko, R. Using Social Media in Project Management: Behavioral, Cognitive, and Environmental Challenges. Project Management Journal 2022, 53, 236–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorhead, S. A.; Hazlett, D. E.; Harrison, L.; Carroll, J. K.; Irwin, A.; Hoving, C. A new dimension of health care: systematic review of the uses, benefits, and limitations of social media for health communication. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2013, 15, e1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senaratne, S.; Ruwanpura, M. Communication in construction: a management perspective through case studies in Sri Lanka. Architectural Engineering and Design Management 2016, 12, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-Y.; Pan, W.; Howard, R. Impact of building information modeling implementation on the acceptance of integrated delivery systems: Structural equation modeling analysis. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 2017, 143, 04017044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, A. J.; Mollaoglu, S. Individuals’ capacities to apply transferred knowledge in AEC project teams. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 2020, 146, 04020016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, A.; Ahn, S.; Rameezdeen, R.; Baroudi, B. Empirical study on implications of mobile ICT use for construction project management. Journal of Management in Engineering 2019, 35, 04019029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhar, S.; Riaz, Z.; Robinson, D. Integration of social media in day-to-day operations of construction firms. Journal of Management in Engineering 2019, 35, 06018003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Guo, L.; Hu, M.; Liu, W. Influence of customer engagement with company social networks on stickiness: Mediating effect of customer value creation. International Journal of Information Management 2017, 37, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aichner, T.; Jacob, F. Measuring the degree of corporate social media use. International Journal of Market Research 2015, 57, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Benitez, J.; Hu, J. Impact of the usage of social media in the workplace on team and employee performance. Information & Management 2019, 56, 103160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolotti, F.; Mattarelli, E.; Vignoli, M.; Macrì, D. M. Exploring the relationship between multiple team membership and team performance: The role of social networks and collaborative technology. Research Policy 2015, 44, 911–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, A.; Hallowell, M. R. Modeling the role of social networks in situational awareness and hazard communication. In Proceedings of the Construction Research Congress 2014: Construction in a Global Network, May 2014; pp. 1752–1761. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Fay, S.; Wang, Q. The role of marketing in social media: How online consumer reviews evolve. Journal of Interactive Marketing 2011, 25, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anders, A. Team communication platforms and emergent social collaboration practices. International Journal of Business Communication 2016, 53, 224–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, L. W.; Turban, D. B.; Hurley, S. K. Cooperating teams and competing reward strategies: Incentives for team performance and firm productivity. Journal of Behavioral and Applied Management 2016, 3, 1054. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J. Y.; No, S. T.; Park, Y. K. Communication network analysis of project teams in Korean building constructions. Applied Mechanics and Materials 2013, 357, 2338–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, M.; Anandh, K.; Saroja, V. Formulating an optimized network model for effective construction management. International Journal of Chemical Sciences 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, A. M. If you love something, let it go mobile: Mobile marketing and mobile social media 4x4. Business Horizons 2012, 55, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvius, G. Analyzing the landscape of Social Media. In Strategic Integration of Social Media into Project Management Practice; IGI Global: [Location of Publisher, if available], 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pati, Debajyoti, and Lesa N. Lorusso. "How to write a systematic review of the literature.". HERD: Health Environments Research & Design Journal 2018, 11, 15–30.

- Valverde-Berrocoso, Jesús, María del Carmen Garrido-Arroyo, Carmen Burgos-Videla, and María Belén Morales-Cevallos. "Trends in educational research about e-learning: A systematic literature review (2009–2018).". Sustainability 2020, 12, 5153. [CrossRef]

- Baghalzadeh Shishehgarkhaneh, Milad, Afram Keivani, Robert C. Moehler, Nasim Jelodari, and Sevda Roshdi Laleh. "Internet of Things (IoT), Building Information Modeling (BIM), and Digital Twin (DT) in construction industry: A review, bibliometric, and network analysis.". Buildings 2022, 12, 1503. [CrossRef]

- Author 1, T. The title of the cited article. Journal Abbreviation 2008, 10, 142–149. [Google Scholar]

- Shishehgarkhaneh, Milad Baghalzadeh, Robert C. Moehler, and Sina Fard Moradinia. "Blockchain in the Construction Industry between 2016 and 2022: A Review, Bibliometric, and Network Analysis.". Smart Cities 2023, 6, 819–845. [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Wang, H.; Khan, A. N. Mechanism to enhance team creative performance through social media: a transactive memory system approach. Computers in Human Behavior 2019, 91, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shehan, A. O., & Assbeihat, J. M.An Investigation of the Impact of Social Media on Construction Project Management. Civ. Eng. J 2021, 7, 153–164. [CrossRef]

- Chinowsky, P. S., Diekmann, J., & O’Brien, J. Project Organizations as Social Networks. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 2010, 136, 452–458. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S., Arif, M., & Akre, V. (2016). Effect of Social Media on Trust in Virtual Project Teams of Construction Sector in Middle East. In Social Media: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly: 15th IFIP WG 6.11 Conference on e-Business, e-Services, and e-Society, I3E 2016, Swansea, UK, September 13–15, 2016, Proceedings 15; 419-429. Springer International Publishing.

- Moorhead, S. A.; Hazlett, D. E.; Harrison, L.; Carroll, J. K.; Irwin, A.; Hoving, C. A new dimension of health care: systematic review of the uses, benefits, and limitations of social media for health communication. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2013, 15, e1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tajudeen, F. P.; Jaafar, N. I.; Ainin, S. Understanding the impact of social media usage among organizations. Information & Management 2018, 55, 308–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Zubielqui, G. C.; Fryges, H.; Jones, J. Social media, open innovation & HRM: Implications for performance. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2019, 144, 334–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parveen, F.; Jaafar, N. I.; Ainin, S. Social media’s impact on organizational performance and entrepreneurial orientation in organizations. Management Decision 2016, 54, 2208–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Jiang, S.; Wang, D. Understanding the effects of social media use on construction project performance: a project manager’s perspective. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management 2022, 29, 551–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyewobi, L.; Adedayo, O. F.; Olorunyomi, S. O.; Jimoh, R. A. Influence of social media adoption on the performance of construction small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in Abuja–Nigeria. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management 2023, 30, 4229–4252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhar, S.; Abeln, J. M. Investigating social media applications for the construction industry. Procedia Engineering 2014, 85, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, A.; Ahn, S.; Rameezdeen, R.; Baroudi, B. Investigation into post-adoption usage of mobile ICTs in Australian construction projects. Engineering, Construction, and Architectural Management 2021, 28, 351–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, J.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Y. Mobile social media in inter-organizational projects: Aligning tool, task and team for virtual collaboration effectiveness. International Journal of Project Management 2018, 36, 1096–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Guo, X.; Vogel, D.; Zhang, X. Exploring the influence of social media on employee work performance. Internet Research 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, J. N. Work groups, structural diversity, and knowledge sharing in a global organization. Management Science 2004, 50, 352–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benitez, J.; Castillo, A.; Llorens, J.; Braojos, J. IT-enabled knowledge ambidexterity and innovation performance in small U.S. firms: The moderator role of social media capability. Information & Management 2018, 55, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Li, H.; Yin, Q. Building information modeling in combination with real time location systems and sensors for safety performance enhancement. Safety Science 2018, 102, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, P. M. The social media revolution: Sharing and learning in the age of leaky knowledge. Information and Organization 2017, 27, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiregi, M.; Navimipour, N. J. A new method for trust and reputation evaluation in the cloud environments using the recommendations of opinion leaders’ entities and removing the effect of troll entities. Computers in Human Behavior 2016, 60, 280–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramton, C. D.; Orvis, K. L.; Wilson, J. M. Situation Invisibility and Attribution in Distributed Collaborations. Journal of Management 2007, 33, 525–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neeley, T. B.; Leonardi, P. M. Enacting knowledge strategy through social media: Passable trust and the paradox of nonwork interactions. Strategic Management Journal 2018, 39, 922–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Jia, J.; Ding, J.; Wu, M.; Wang, D. Examining the impact of social media use on project management performance: Evidence from construction projects in China. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 2021, 147, 04021004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, S. S. C.; Li, E. Y.; Wu, Y.-L.; Hou, O. C. L. Understanding Web 2.0 service models: A knowledge-creating perspective. Information & Management 2011, 48, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pee, L. G.; Lee, J. Intrinsically motivating employees’ online knowledge sharing: Understanding the effects of job design. International Journal of Information Management 2015, 35, 679–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Y. A.; Ahmad, M. N.; Ahmad, N.; Zakaria, N. H. Social media for knowledge-sharing: A systematic literature review. Telematics and Informatics 2019, 37, 72–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsharo, M.; Gregg, D.; Ramirez, R. Virtual team effectiveness: The role of knowledge sharing and trust. Information & Management 2017, 54, 479–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molm, L. D.; Takahashi, N.; Peterson, G. Risk and trust in social exchange: An experimental test of a classical proposition. American Journal of Sociology 2000, 105, 1396–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, G.; Osei-Bryson, K.-M. Exploration of factors that impact voluntary contribution to electronic knowledge repositories in organizational settings. Knowledge Management Research & Practice 2013, 11, 288–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-J.; Hung, S.-W. To give or to receive? Factors influencing members’ knowledge sharing and community promotion in professional virtual communities. Information & Management 2010, 47, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H. H.; Chuang, S.-S. Social capital and individual motivations on knowledge sharing: Participant involvement as a moderator. Information & Management 2011, 48, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briscoe, F.; Rogan, M. Coordinating complex work: Knowledge networks, partner departures, and client relationship performance in a law firm. Management Science 2016, 62, 2392–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, R.; Lai, C.-H. Microcoordination 2.0: Social coordination in the age of smartphones and messaging apps. Journal of Communication 2016, 66, 834–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treem, J. W.; Leonardi, P. M. Social media use in organizations: Exploring the affordances of visibility, editability, persistence, and association. Annals of the International Communication Association 2013, 36, 143–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond-Barnard, T. J.; Fletcher, L.; Steyn, H. Linking trust and collaboration in project teams to project management success. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business 2018, 11, 432–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Cao, X.; Liu, Z.; Wang, J. Excessive social media use at work: Exploring the effects of social media overload on job performance. Information Technology & People 2018, 31, 1091–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majchrzak, A.; Faraj, S.; Kane, G. C.; Azad, B. The Contradictory Influence of Social Media Affordances on Online Communal Knowledge Sharing. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 2013, 19, 38–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, S.; Mehboob, F.; Sirshar, M. Social Media Collaboration in Software Project Management. [Journal/Conference Name] 2019, [Volume or Issue Number, if available], [Page numbers if available]. [Google Scholar]

- Juarez-Ramirez, R.; Pimienta-Romo, R.; Ocegueda-Miramontes, V. Supporting the software development process using social media: Experiences with student projects. In Proceedings of the 37th Annual Computer Software and Applications Conference Workshops, 2013; IEEE: [Location of Conference, if available], 2013; pp. 656–661. [Google Scholar]

- Mathieu, J. E.; Schulze, W. The Influence of Team Knowledge and Formal Plans on Episodic Team Process-Performance Relationships. Academy of Management Journal 2006, 49, 605–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, M. A.; Mathieu, J. E.; Zaccaro, S. J. A Temporally Based Framework and Taxonomy of Team Processes. Academy of Management Review 2001, 26, 356–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepine, J. A.; Piccolo, R. F.; Jackson, C. L.; Mathieu, J. E.; Saul, J. R. A Meta-Analysis of Teamwork Processes: Tests of a Multidimensional Model and Relationships with Team Effectiveness Criteria. Personnel Psychology 2008, 61, 273–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, J. B. H.; Leong, W. J.; Skitmore, M. Capitalising teamwork for enhancing project delivery and management in construction: empirical study in Malaysia. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management 2020, 27, 1479–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keil, A.; Friedrich, R.; Doppelfeld, D. Organizational Success and Failure Criteria in Virtual Team Maturity. In: Developing Organizational Maturity for Effective Project Management; IGI Global, 2018.

- Salvation, M. D. Communication and Conflict Resolution in the Workplace. Dev Sanskriti Interdisciplinary International Journal 2019, 13, 25-46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krancher, O., Dibbern, J., & Meyer, P. How social media-enabled communication awareness enhances project team performance. Journal of the Association for Information Systems 2018, 19, 813-856. [CrossRef]

- Cummings, J. N., Espinosa, J. A., & Pickering, C. K. Crossing Spatial and Temporal Boundaries in Globally Distributed Projects: A Relational Model of Coordination Delay. Information Systems Research 2009, 20, 420-439. [CrossRef]

- Rimkuniene, D., & Zinkeviciute, V. Social media in communication of temporary organisations: role, needs, strategic perspective. Journal of Business Economics and Management 2014, 15, 899-914. [CrossRef]

- Cleland, D. , & Lewis, R. I. 2002. Project Management: Strategic Design and Integration. McGraw-Hill.

- Kluger, A. N., & Denisi, A. The Effects of Feedback Interventions on Performance: A Historical Review, a Meta-Analysis, and a Preliminary Feedback Intervention Theory. Psychological Bulletin 1996, 119, 254-284. [CrossRef]

- Fishbach, A., Eyal, T., & Finkelstein, S. R. How Positive and Negative Feedback Motivate Goal Pursuit. Social and Personality Psychology Compass 2010, 4, 517-530. [CrossRef]

- Williamson, H. 1975. Privacy and housing: A gap between the behavioral scientist and the architect. Proceedings of the Human Factors Society Annual Meeting, SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, 21-23.

- Russell, A., Staub-French, S., Tran, N., &Wong,W. Visualizing high-rise building construction strategies using linear scheduling and 4D CAD. Automation in Construction 2009, 18, 219-236. [CrossRef]

- Li, X. Y., & Zhang, Z. G. Generation of the 3D CAD Model of Construction Building. Advanced Materials Research 2012, 346, 83-89. [CrossRef]

- Wolff, F. 2020. Preliminary Conclusions. Yiddish Revolutionaries in Migration. Brill.

- Hosny, A.-H., & El-Nahhas, F. Role of geotechnical monitoring in quality management of tunnelling projects. International Journal of Rock Mechanics and Mining Sciences and Geomechanics Abstracts 1995, 135A.

- London, M., & Sessa, V. I. Group feedback for continuous learning. Human Resource Development Review 2006, 5, 303-329. [CrossRef]

- London, M. 2003. Job feedback: Giving, seeking, and using feedback for performance improvement. Psychology Press.

- London, M., Polzer, J. T., & Omoregie, H. Interpersonal congruence, transactive memory, and feedback processes: An integrative model of group learning. Human Resource Development Review 2005, 4, 114-135. [CrossRef]

- Gabelica, C., Van den Bossche, P., Segers, M., & Gijsealers,W. Feedback, a powerful lever in teams: A review. Educational Research Review 2012, 7, 123-144. [CrossRef]

- Gabelica, C., Van den Bossche, P., De Maeyer, S., Segers, M., & Gijsealers,W. The effect of team feedback and guided reflexivity on team performance change. Learning and Instruction 2014, 34, 86-96. [CrossRef]

- Kermanshachi, S. US multi-party standard partnering contract for integrated project delivery. Mississippi State University, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rentsch, J. R. , Mello, A. L., & Delise, L. A. Collaboration and meaning analysis process in intense problem solving teams. Theoretical Issues in Ergonomics Science 2010, 11, 287–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M. J. Negotiation in collaborative problem-solving dialogues. NATO ASI SERIES F COMPUTER AND SYSTEMS SCIENCES 1995, 142, 39–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S. , & Califf, C. Social media-induced technostress: Its impact on the job performance of IT professionals and the moderating role of job characteristics. Computer Networks 2017, 114, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero, E. , Adán, A., & Cerrada, C. Site managers’ daily work and the uses of building information modelling in construction site management. Sensors 2015, 15, 15988–16008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Duff, A. , Robertson, I., Phillips, R., & Cooper, M. Improving safety by the modification of behaviour. Construction Management and Economics 1994, 12, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, I. , & Duff, R. Use of performance measurement and goal setting to improve construction managers’ focus on health and safety. Construction Management and Economics 2007, 25, 869–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tretheway, R. The effect of feedback on risk-taking in the Australian construction industry. Journal of Engineering Design and Technology 2005, 3, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabri, M. Team feedback based on dialogue: Implications for change management. Journal of Management Development 2004, 23, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L. , Zhang, Y., Dai, F., Yoon, Y., Song, Y., & Sharma, R. S. Social media data analytics for the US construction industry: Preliminary study on Twitter. Journal of Management in Engineering 2017, 33, 04017038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparer, E. H. , Herrick, R. F., & Dennerlein, J. T. Development of a safety communication and recognition program for construction. New solutions: a journal of environmental and occupational health policy 2015, 25, 42–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayi, S. , Adegbenro, O., Alaka, H., Oyegoke, A., & Manu, P. Addressing behavioral safety concerns on Qatari Mega projects. Journal of Building Engineering 2021, 41, 102398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senior, B. Team roles and team performance: is there ‘really’ a link? Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 1997, 70, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senaratne, S., & Ruwanpura, M. Communication in construction: a management perspective through case studies in Sri Lanka. Architectural Engineering and Design Management 2016, 12, 3-18. [CrossRef]

- Hasan, A., Elmualim, A., Rameezdeen, R., Baroudi, B., & Marshall, A. An exploratory study on the impact of mobile ICT on productivity in construction projects. Built Environment Project and Asset Management 2018, 8, 320–332. [CrossRef]

- Anumba, C. J. , & Wang, X. (2012). Mobile and pervasive computing in construction: an introduction. In Mobile and Pervasive Computing in Construction, 1-10.

- Chen, Y., & Kamara, J. M. A framework for using mobile computing for information management on construction sites. Automation in Construction 2011, 20, 776–788. [CrossRef]

- Son, H., Park, Y., Kim, C., & Chou, J.-S.Toward an understanding of construction professionals’ acceptance of mobile computing devices in South Korea: An extension of the technology acceptance model. Automation in Construction 2012, 28, 82-90. [CrossRef]

- Chinowsky, P. S., Diekmann, J., & O’Brien, J. Project organizations as social networks. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 2010, 136, 452–458. [CrossRef]

- Al-Shehan, A. O., & Assbeihat, J. M. An Investigation of the Impact of Social Media on Construction Project Management. Civ. Eng. J 2021, 7, 153–164. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S. , Arif, M., &; Akre, V. (2016). Effect of Social Media on Trust in Virtual Project Teams of Construction Sector in Middle East. In Social Media: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly: 15th IFIP WG 6.11 Conference on e-Business, e-Services, and e-Society, I3E 2016, Swansea, UK, September 13–15, 2016, Proceedings (Vol. 15, pp. 419-429). Springer.

- Jafar, R. M. S. , Geng, S., Ahmad, W., Niu, B., & Chan, F. T. (2019). Social media usage and employee’s job performance: The moderating role of social media rules. Industrial Management & Data Systems.

- Papa, A. , Santoro, G., Tirabeni, L., & Monge, F. Social media as a tool for facilitating knowledge creation and innovation in small and medium enterprises. Baltic Journal of Management, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janes, S. H., Patrick, K., & Dotsika, F. Implementing a social intranet in a professional services environment through Web 2.0 technologies. The Learning Organization 2014, 21, 26–47. [CrossRef]

- Cardon, P.W., & Marshall, B. The hype and reality of social media use for work collaboration and team communication. International Journal of Business Communication 2015, 52, 273–293. [CrossRef]

- Walker, D. , & Garrett, D. (2016). Inside the Project Management Institute: Setting up Change Makers for Success Based on Social Connection. IGI Global.

- Bird, R., & Harris, S. (2017). Innovations in Educating and Building the Paediatric Theatre Team. The use of Social Media. MedEdPublish, 6.

- Chinowsky, P., Diekmann. Chinowsky, P., Diekmann, J., & O’Brien, J. Project Organizations as Social Networks. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management-ASCE 2010, 136, 452-458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynne, A., Challa, C., Palesis, J., & Farkas, B. A Conceptual Model: Impact of Usage of Social Media Tools to Enhance Project Management Success. Portuguese Journal of Management Studies. 2015, 20, 55-71.

- Nisar, T., Prabhakar, G., & Strakova, L. Social media information benefits, knowledge management and smart organizations. Journal of Business Research 2019. [CrossRef]

- Nagendra, A. Paradigm Shift in HR Practices on Employee Life Cycle Due to Influence of Social Media. Procedia. Economics and finance 2014, 11, 197-207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, J. , Wilson, A., Galliers, R., & Bynghall, S. (2017). Social Media and the Emergence of Reflexiveness as a New Capability for Open Strategy. Strategic Information Management.

- Sundaramoorthy, V., & Bharathi, B. Need for social media approach in software development. Indian Journal of Science and Technology 2016, 9, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Ninan, J., Mahalingam, A., Clegg, S., & Sankaran, S. ICT for external stakeholder management: sociomateriality from a power perspective. Construction Management and Economics, 2020, 38, 840-855. [CrossRef]

- Ball, T., & Nash-Williams, G. Communication to Reduce Dependency and Enhance Empowerment Using ’New’ Media: Evidence from Practice in UK Flood Risk Areas. Journal of Extreme Events 2023, 2241003. [CrossRef]

- Vithayathil, J., Osiri, J., & Dadgar, M. Does Social Media Use at Work Lower Productivity. International Journal of Information Technology and Management 2020, 19, 47–67. [CrossRef]

- Cao, X., & Ali, A. Enhancing Team Creative Performance through Social Media and Transactive Memory System. International Journal of Information Management 2018, 39, 69–79. [CrossRef]

- Kanagarajoo, M. V., Fulford, R., & Standing, C. The Contribution of Social Media to Project Management. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management 2020, 69, 834–872. [CrossRef]