1. Introduction

Kaposi sarcoma is an angioproliferative tumor that affects the epithelial or mucous membranes. The causing agent is Human Herpes Virus 8 (HHV-8) also known as Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV). HHV-8 infections are usually asymptomatic with more aggressive pathogenesis involving immunosuppression [2]. The virus interferes with genes responsible for cell cycle regulation, which allows for uncontrolled cell proliferation. Kaposi sarcoma is considered an AIDS-defining illness for patients with a confirmed seropositive HIV diagnosis [2]. A review conducted by Goncalves et. al found that in the United States, Kaposi sarcoma is the most frequent tumor arising in the setting of HIV infection [1,4]. HIV-related Kaposi sarcoma can lead to more advanced immunosuppression and, if left untreated, is more likely to involve viscera and surrounding lymph nodes [2]. Approximately 15% of Kaposi sarcoma patients display visceral involvement [1,4]. Early recognition and treatment of disseminated Kaposi sarcoma can help improve patient outcomes.

2. Objective

To describe the clinical evaluation and management of disseminated Kaposi sarcoma disease presentation.

3. Case Presentation

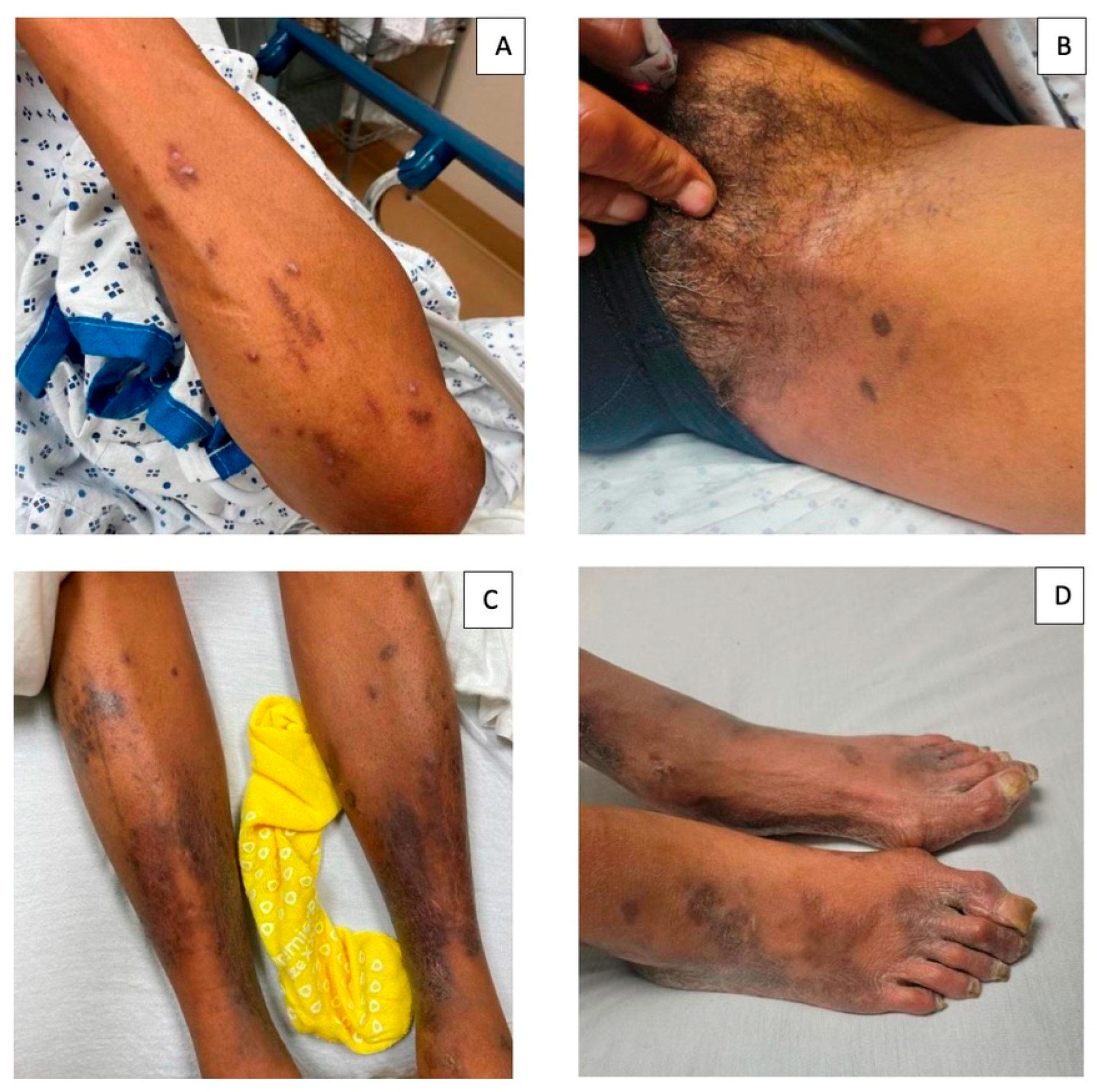

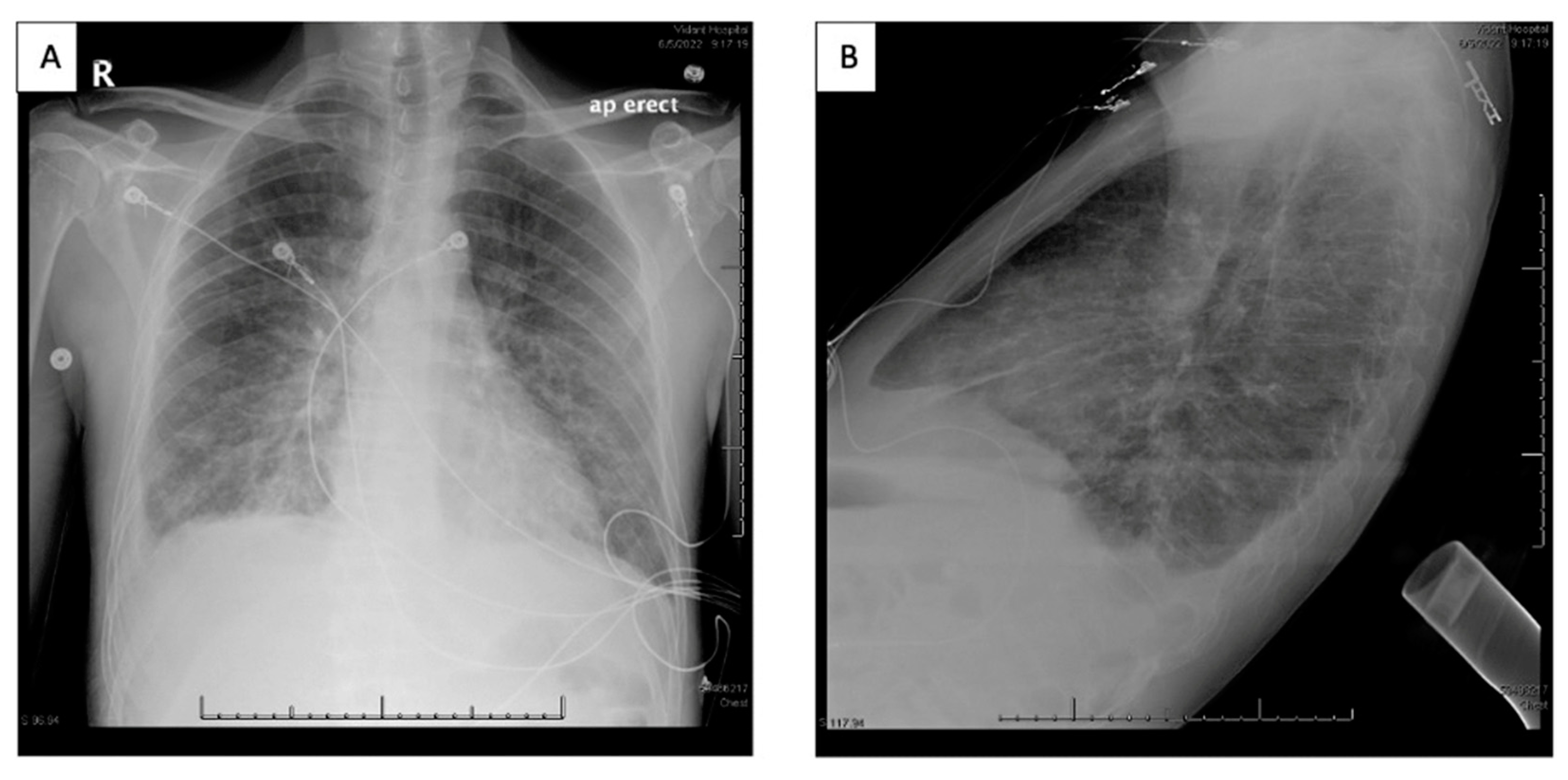

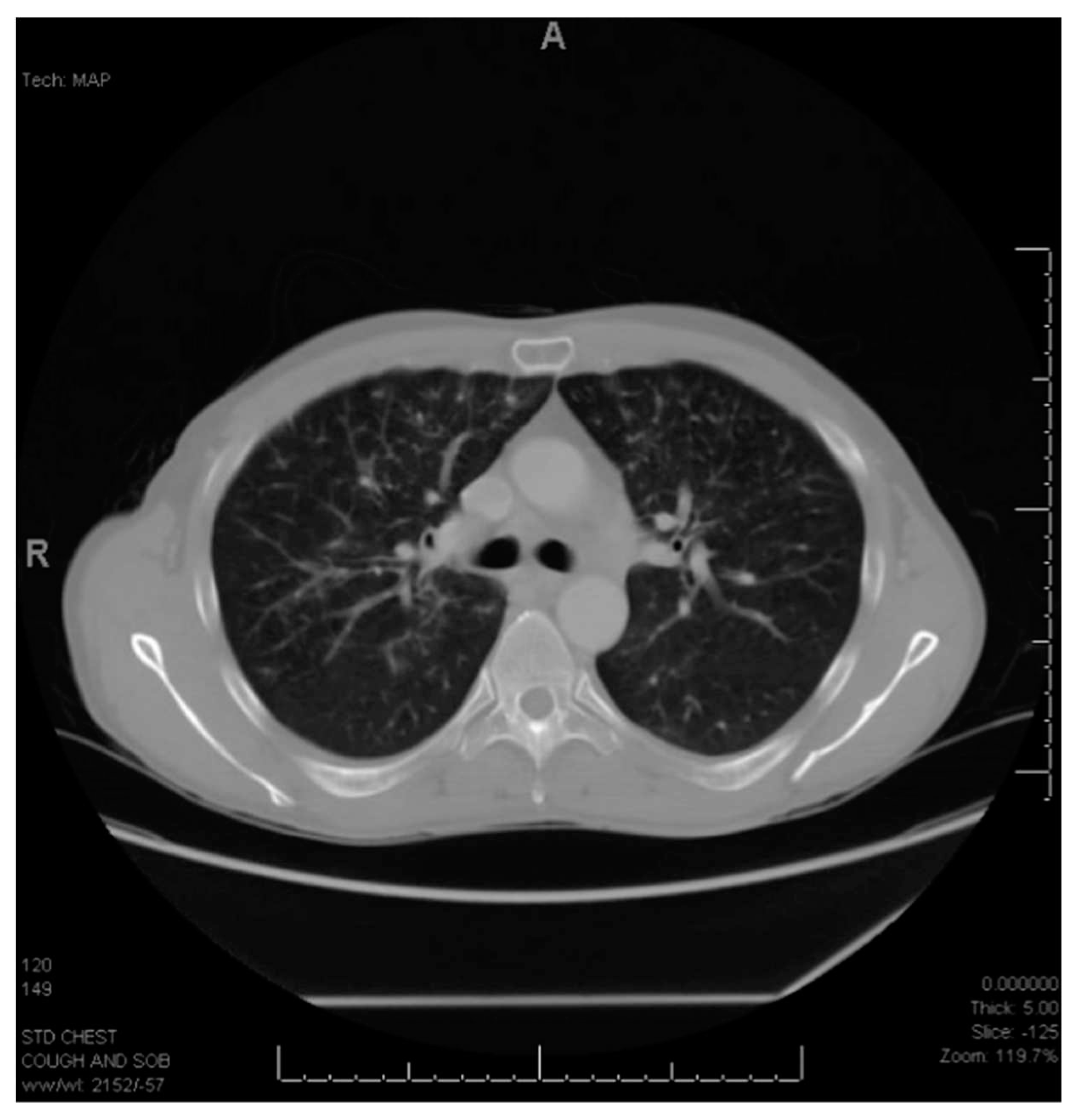

A 49-year-old African American male with a 20-year history of HIV, noncompliant on HAART returned for care to the HIV clinic after two years and was admitted to the hospital with complaints of worsening shortness of breath, nonproductive cough, significant unintentional weight loss and new hyperpigmented skin lesions [

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3]. CD4 count was less than 100 and HAART was restarted along with TMP-SMX. Biopsy of skin lesions confirmed Kaposi sarcoma. Work-up was done for his respiratory symptoms and opportunistic infections were ruled out [Figures 4–7]. Chest imaging showed patchy and nodular ground glass infiltrates with bilateral small pleural effusions [Figures 5 and 6]. Bronchoscopy with endobronchial ultrasound, bronchoalveolar lavage and fine-needle aspiration cytology were performed due to concern for Kaposi’s sarcoma lung involvement. Findings were suspicious of Kaposi involvement, however, were atypical [hemosiderin laden macrophages]. The patient was discharged home with hematology/oncology and infectious disease follow-up as outpatient. While he was being worked up outpatient to rule out systemic involvement of Kaposi’s sarcoma, he developed a worsening left lateral foot lesion with pain and new purulent drainage and was readmitted to the hospital for concern of infection and underlying osteomyelitis. MRI of the left foot showed findings concerning for osteomyelitis. The patient received debridement with deep cultures and biopsy, which ruled out osteomyelitis and superficial wound infection. While in the hospital he was also worked up for Kaposi sarcoma systemic involvement by esophagogastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy, which showed lesions in the esophagus, stomach, duodenum, and rectum [

Figure 4 and Figure 5]. Biopsy specimen from nodular erythematous rectal mucosa returned positive for Kaposi’s Sarcoma confirming systemic involvement. Chemotherapy was initiated with liposomal doxorubicin after checking his baseline echocardiogram, which was normal.

4. Discussion

This case illustrates the significance of implementing prompt diagnostic measures for visceral Kaposi sarcoma detection. Kaposi sarcoma is the most common neoplastic disease associated with HIV infection [

1,4]. The pathogenesis of Kaposi sarcoma in patients with a confirmed seropositive HIV diagnosis involves interactions between various cell types, most commonly endothelial and epithelial cells [

2,

3,5,6]. The main etiologic agent is Human Herpes Virus 8 (HHV-8), which interacts with key immune system regulators to evade the body’s defense signaling pathway. In addition, HHV-8 undergoes periods of latency in host cells followed by sporadic lytic reactivation. This allows the virus to survive and continue to undergo uncontrolled proliferation [

4,

5]. The HIV-related Kaposi sarcoma subtype represents the most aggressive form [

4].

The most common clinical presentations of Kaposi sarcoma involve red or brown papules visible on the skin of patients’ extremities. Visceral progression of Kaposi sarcoma develops as part of continued progression of cutaneous Kaposi sarcoma [

5]. Extracutaneous areas of Kaposi sarcoma progression include the oral cavity, lungs, liver, intestines, and lymph nodes [

6,

7]. Signs and symptoms indicating visceral involvement of Kaposi sarcoma include lymphoedema, shortness of breath, chest pain, hemoptysis, gastrointestinal abnormalities, and generalized malaise or fatigue [

7,

8]. Pulmonary and gastrointestinal lesions are often considered life threatening. Pulmonary involvement is the most common visceral manifestation [

3,

8]. In the lungs, Kaposi sarcoma presents with mass lesions or obstructions [

6]. Gastrointestinal lesions while usually asymptomatic can cause bleeding or obstruction [

7]. The use of imaging techniques is recommended to prevent complications from visceral Kaposi sarcoma progression.

As discussed previously, pulmonary, and gastrointestinal involvement are the most complicated presentations of visceral Kaposi sarcoma development. Due to the direct effects of gastrointestinal involvement on the patient’s quality of life, this type of progression is more easily detected as opposed to pulmonary involvement. Common symptoms impacting quality of life include increased pain or bleeding, postprandial discomfort, diarrhea, obstruction, and malabsorption. Imaging techniques aimed at diagnosis of spread to gastrointestinal areas include esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and colonoscopy [

7]. Pulmonary impact holds a worse prognosis. In the absence of detection and initiation of treatment, the expected survival time is less than six months. However, the incidence of pulmonary manifestations in HIV-related Kaposi sarcoma is approximately 30%, which can make early detection more challenging [

8]. Chest radiograph and CT scans often offer poor findings. Bronchoscopy holds the highest diagnostic value in the setting of suspected visceral Kaposi sarcoma progression [

8].

5. Conclusion

Initial clinical management for HIV-related Kaposi sarcoma focuses on bolstering the immune system. As such, combined antiretroviral therapy (cART) is considered a first-line approach [

4]. This approach aims to reduce cutaneous lesions and halt visceral dissemination. Treatment is also determined by clinical staging. In the setting of T1 advanced-stage or progressive manifestations of HIV-related Kaposi sarcoma, treatment shifts to chemotherapeutic approaches. Liposomal anthracyclines are the preferred treatment for advanced HIV-related Kaposi sarcoma [

4,

8]. Prompt detection of visceral involvement in Kaposi sarcoma patients can improve prognosis. A systemic review of randomized trials found that the expected three-year survival rate for HIV-related Kaposi sarcoma patients staged at T0 who were started on systemic chemotherapy was 88% compared to patients with progression beyond the T1 stage who displayed an average survival rate of 53% after chemotherapeutic intervention [

2,

4]. The goals of therapy for HIV-related Kaposi sarcoma patients with advanced disease should focus on mitigating end-organ damage and improving long-term survival.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Priscila H. Goncalves, Thomas S. Uldrick, Robert Yarchoann. HIV-associated Kaposi sarcoma and related diseases. AIDS. 2017; 31(14): 1903-1916. [CrossRef]

- Reid E, Suneja G, Ambinder RF, et al. AIDS-Related Kaposi Sarcoma, Version 2.2019. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019;17(2):171-189. [CrossRef]

- Chunshuang Guan, Yuxin Shi, Jinxin Liu, et al. Pulmonary involvement in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma: a descriptive analysis of thin-section manifestations in 29 patients. 2021; 11(2): 714-724. [CrossRef]

- Ethel C, Blossom D, Krown SE, Martin J, Bower M, Whitby D. Kaposi sarcoma (Primer). Nature Reviews: Disease Primers. 2019;5(1). [CrossRef]

- Karabajakian A, Ray-Coquard I, Blay J-Y. Molecular Mechanisms of Kaposi Sarcoma Development. Cancers. 2022; 14(8):1869. [CrossRef]

- Indiran Govender, Mogakgomo H. Motswaledi, Langalibalele H. Mabbuzza. A case report of the rapid dissemination of Kaposi’s sarcoma in a patient with HIV. African Journal of Primary Health Care & Family Medicine. 2013; 5(1). [CrossRef]

- Cesarman E, Damania B, Krown SE, Martin J, Bower M, Whitby D. Kaposi sarcoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019; 5(1):9. [CrossRef]

- Diaz R, Almeida P, Morgan D. Rare presentation of bronchopulmonary Kaposi sarcoma. BMJ Case Reports. 2019; 12(8). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).