There are approximately 6.7 million people over the age of 65 in the United States (U.S.) who are currently living with Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia (Alzheimer’s Association, 2023). This number is projected to rise to 13.8 million by 2060 unless significant scientific advancements occur (Rajan et al., 2021). More than 11 million informal caregivers attend to the health and well-being needs of their loved ones with dementia (U.S. Census Bureau, 2022). Recent estimates suggest that this contribution of time, energy, and resources is equal to 18 billion hours of unpaid care or $339.5 billion per year (Alzheimer’s Association, 2023).

While the hourly and monetary costs of providing care for a person with dementia may be more easily quantified, it is more challenging to account for the costs family caregivers incur from a physical, emotional, social, and spiritual health standpoint (Thompson et al. 2005). Little is known about how internal positive psychological resources, such as hope, serve to lessen the experience of burden among family caregivers, although there is evidence that it is important (Author et al., 2022a, 2023a, 2023b). Prior research on hope and caregiving has considered hope from a unidimensional perspective. The current study, however, expands this research by examining hope as a multi-dimensional construct. An overview of the published research on caregiver stress and burden, hope theory, and hope and caregiving are provided as background information for the study.

1. Caregiver Stress and Burden

Burden amongst caregivers has been associated with physical (e.g., sleep difficulties, cardiovascular disease, reduced immune response, etc.), emotional (e.g., mental health difficulties), social and lifestyle changes (e.g., relationship challenges, lower social engagement (Park et al., 2020; Kazmer et al., 2018, Thompson, et al., 2005), and spiritual struggles (Author, 2023a). Based on meta-analyses, prevalence rates of thirty-one percent for depression (Collins & Kishita; 2019) and forty-two percent for anxiety (Kaddour & Kishita, 2020) has been predicted among caregivers of persons with dementia. Contributing to emotional health concerns, caregivers may limit their own self-care activities, given the demands on their time, which may lead to interrupted life goals and appraising the role of caregiver as burdensome (Kazmer et al., 2018).

Additionally, caregiver burden may have a direct impact on mortality rates in persons with dementia according to a recent study (Shulz et al., 2021). The reasons for increased mortality rates in persons with dementia may be, in part, due to an increase in harmful behaviors towards persons with dementia (Beach, et al., 2005) and not meeting their care needs (Beach & Shulz, 2017), although additional research is needed to better understand this phenomenon. There is evidence that caregiver burden may lead to early placement in long-term care settings (i.e., skilled nursing) which tends to hasten time to death for persons with dementia, although social services may allow for persons with dementia to live in the homes of their loved ones longer (Author et al., 2019).

There are several sociodemographic factors that may influence burden perceptions in caregivers such as age, gender, and the relationship between the caregiver and the care recipient. More specifically, caregivers in mid-life and between the ages of 65 and 74 tend to have more responsibilities outside of caregiving than those who are over the age of 75 which may lead to a greater sense of burden (Tsai et al., 2021). Additionally, caregiver gender may influence burden perceptions with those identifying as female reporting more burden than those identifying as male (Arbel et al., 2019; Kokorelias et al, 2021). Research also suggests that wives tend to experience greater burden than husbands (Chappell et al., 2015). Perceived social support is a well-known protective factor against burden based on a recent meta-analysis (Del-Pino-Casado et al., 2018).

2. Hope Theory

Snyder’s (1995) hope theory is perhaps the most robust and well-researched model of hope. This theory conceptualizes hope as an active process comprised of two dimensions which work in synergy to empower and encourage persons amid stressful life circumstances (Snyder et al., 2000). One dimension of hope, hope-agency (“I can do this”), refers to the extent to which a person believes they have the capacity to progress towards an intended goal (Snyder, 1995). A second dimension of hope, hope-pathway (“How can I do this?”) is the extent to which a person believes they know the means or methods for attaining their goal (Snyder, 1995). Several studies have validated the efficacy of independent hope-agency and hope-pathway dimensions (Geraghty et al., 2010). Hope-agency, which has to do with self-efficacy and a sense of personal control, may be a more robust predictor than hope-pathway for coping (Bailey et al., 2007) and has demonstrated the capacity to uniquely predict positive coping in specific stressful situations (Drach-Zahavy & Somech, 2002), although it has not been studied in caregivers of persons with dementia.

3. Hope and Caregiving

There is evidence that hope is a protective resource against burden in caregivers of people with dementia when compared to other positive psychological factors such as social intelligence, zest, and love (García-Castro et al., 2020). Additionally, greater levels of hope in caregivers tend to be associated with fewer symptoms of depression (Adams, 2008). The theory of “Renewing Everyday Hope” (Duggleby et al., 2009, p. 520), which emerged from a grounded theory qualitative study, posits that hope among caregivers can be likened to an interconnected ‘knot’ that involves coming to terms with a loved one’s condition as well as the caregivers own lived experiences; finding positives in these circumstances by weighing pros and cons; connecting with others and faith; and seeing possibilities for the future by setting goals and making choices.

4. The Current Study

The purpose of the current study was to examine the relationship between stress, two dimensions of hope, and perceived burden in a sample of family caregivers of persons with dementia. The caregiving stress process model (Pearlin et al., 1990; Pearlin & Bierman, 2013) provided a framework for variable selection and specification aimed at addressing the complexity of the caregiving experience. Stress, in this model is categorized as primary or secondary, with primary stress involving the objective demands of caregiving (i.e., amount of physical care required, degree of cognitive impairment in the care recipient, etc.) and the degree to which the caregiver appraises these demands as being stressful. Secondary stress accounts for sources of strain not directly related to, but consequential to the caregiving role such as contextual or background variables such as the sociodemographic profiles of caregivers and care recipients. Internal positive psychosocial resources, such as hope, are considered and may directly contribute to reducing the untoward effects of caregiver stress which can lead to burden. Internal and external resources (i.e., social support) may also mediate or moderate relationships among contextual factors, stressors, and caregiver outcomes in this model.

The aims of the current study were to: 1) examine the degree to which hope-agency and hope-pathway are related to perceived burden among family caregivers of persons with dementia; 2) to examine if hope-agency and hope-pathway independently and significantly contribute to explaining variation in burden among family caregivers of persons with dementia; and 3) to determine if hope-agency and hope-pathway independently and significantly mediate the relationship between stress and burden among family caregivers of persons with dementia.

5. Method

5.1. Study Design

A cross-sectional quantitative research design was used in this study with a convenience sample in a large metropolitan area [removed for review]. This research project was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the two academic institutions [removed for review] prior to any study activities. The study was open to adults 21 years and older who self-identified as a family caregiver of a person diagnosed with probable Alzheimer’s disease or another form of dementia who was aged 65 or older. The ability to read and speak English was an inclusion criterion. Exclusion criteria was a diagnosis of dementia on the part of the caregiver and serious untreated mental illness.

Recruitment strategies involved distribution of flyers about the study to organizations who serve people with dementia and their family members and community presentations about the study to professionals (i.e., nurses, physicians, social workers, chaplains) who serve this population. After screening for eligibility, potential participants went through an informed consent process. Upon consent, they were invited to complete a packet of self-report measures in the English language.

Sample size was based on a priori power analysis to find significance with a desired power of 0.80 an α-level at .05, and a moderate-small effect size of .15 (f2). For a multiple linear regression model with seven predictor variables, the minimum sample size needed was 103. Thus, the obtained sample size of 155 participants was adequate.

5.2. Variables and Measures

Standardized measures were used to assess the variables of hope, caregiver burden, and stress while intensity of care, social support, and demographic/background were measured with investigator developed measures. Variables and corresponding measures are described in below in detail.

5.2.1. Outcome Variable

Caregiver Burden. Caregiver burden was measured using the Zarit Burden Inventory (Zarit et al., 1980). This 22-item, self-report tool assesses the degree of perceived burden among caregivers of adults with dementia. Response options are presented on a 5-point, Likert Scale, ranging from 0 (Never) to 4 (Nearly Always). This measure demonstrated good to excellent internal consistency in prior studies (Cronbach α = .92; Hébert et al., 2000). Excellent reliability was demonstrated in the current study (Cronbach α = .93).

5.2.2. Predictor Variables

Hope. The 12-item Adult Hope Scale (Snyder et al., 1991) was used to measure caregivers’ internal resources using two dimensions of hope (Snyder et al., 1991); hope-agency and hope pathway (which were discussed in the background section of this article). This measure has demonstrated adequate reliability for each dimension in previous studies (DiGasbarro et al., 2019). In the current study, good internal consistency for the hope-agency (Cronbach’s α = .82) and the hope-pathway (Cronbach’s α = .84) subscales were demonstrated.

Caregiver Stress. The distress subscale of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire (NPI; Cummings et al., 1994) was used to assess participants’ subjective stress. The distress subscale measures the degree to which caregivers are distressed by the presence, severity, and frequency of 12 challenging behaviors associated with dementia. Content validity, concurrent validity, inter-rater reliability, and test-retest reliability of the NPI distress subscale is well established (Cummings et al., 1994). This subscale demonstrated good reliability in this study (Cronbach’s α = .85).

Intensity of Care. The investigators developed an Intensity of Care index to objectively assess participants’ objective stress. This additive index was created by summing responses to two survey items: 1) the average number of hours per day spent providing direct care for the person with dementia; and 2) the number of people cared for (which could also include other family members such as children).

Secondary Stressors. The measures used for secondary stressors were caregiver age, gender, and marital status. These data were gathered using a series of demographic self-report items.

Social Support. In the current study, the external resource of social support was assessed through utilization of a clinical measure that was part of an intake packet at the center where the study was conducted. This measure is comprised of 4 items using a 5-point, Likert Scale, ranging from Strongly Agree to Strongly Disagree. The higher the score on this measure, the greater the social support. Although this social support measure is not standardized, it demonstrated adequate internal consistency in the current study (Cronbach α = .78).

5.3. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 27. To examine the aims of the study, we first calculated descriptive statistics for participants’ demographics/background variables and the other variables of interest. See

Table 1 and

Table 2. Next, we analyzed correlations between the outcome variable (burden), the measures for stress, objective and subjective primary stressors, secondary stressors, and measures for external and internal resources. Third, we developed a series of stepwise hierarchical regression models to examine the independent effect that each dimension of hope had on explaining variation in caregiver burden when controlling for primary objective and subjective stressors, secondary stressors, and social support as an external resource. Additional diagnostic analyses assessed for multicollinearity between the independent variables in the regression models. Finally, mediation models were constructed to test whether hope-agency had a mediating effect on the relationship between our measure of subjective stress and burden.

6. Results

6.1. Sample Demographics and Descriptive Statistics

One-hundred and fifty-five caregivers were included in the study. The average age of participants was 65 years (

SD = 11.06). Most identified as female (70.6%;

n = 108) and as White or Caucasian (94.8%,

n = 145). A majority indicated that they were married (90.8%,

n = 138), and the largest group of participants reported being spousal caregivers (66.2%,

n = 100). A smaller group reported being an adult child or grandchild (23.2%,

n = 35).

Table 1 provides additional demographic data, and

Table 2 provides a descriptive profile of the sample’s responses for key variables under analysis in the current study.

6.2. Correlates of Burden

To address the first aim of the study, correlates of burden were examined. Perceived burden was positively related to objective stress, r = 0.23, p < .01; subjective stress, r = .62, p < .001; and caregiver gender, r = 0.27, p <.01. There was a significant negative association between burden and the external resource of social support, r = -0.22, p < .05. There were no correlations between burden and age or marital status. Supporting our hypothesis, we found that burden was negatively associated with the hope-agency, r = -0.33, p < .001 and hope-pathway, r = -0.24, p < .01. See

Table 3.

6.3. Independent Effects of Hope Measures on Caregiver Burden

To address the second aim of the study, a series of stepwise hierarchical regression models for predicting burden were developed. We tested for a significant change in R2 (∆R2) between the base model and models that included both hope dimensions.

Model 1 served as the base model and included measures of subjective stress, primary and secondary objective stress, and the external resource of social support. The base model revealed that subjective stress (β = 0.566, p < 0.001) and caregiver gender (β = 0.266, p < 0.001) were significantly related to burden. In other words, caregivers who identified as female with higher levels of subjective stress also had higher levels of burden. Standardized betas revealed that subjective stress was the strongest predictor in the base model for burden.

For models 2 and 3, measures of hope-agency and hope-pathway were introduced in a stepwise fashion to test whether each of these dimensions had an independent effect on burden. Results for model 2 suggested that the inclusion of hope-agency improved the fit of the model and accounted for a 4.93% increase in the explained variance in burden. Further, hope-agency had a significant negative relationship with burden (

β = -0.182, p < 0.05). As hope-agency increased, burden decreased. Model 3 revealed that hope-pathway did not have the same effect and was not significantly related to burden. See

Table 4 for standardized OLS coefficients.

6.4. Hope Mediation Effects on Caregiver Distress and Burden Relationship

To address our third aim, mediation analyses were conducted. Because hope-pathway was not a significant predictor of burden when controlling for subjective stress, this variable was excluded from analysis and only hope-agency was tested.

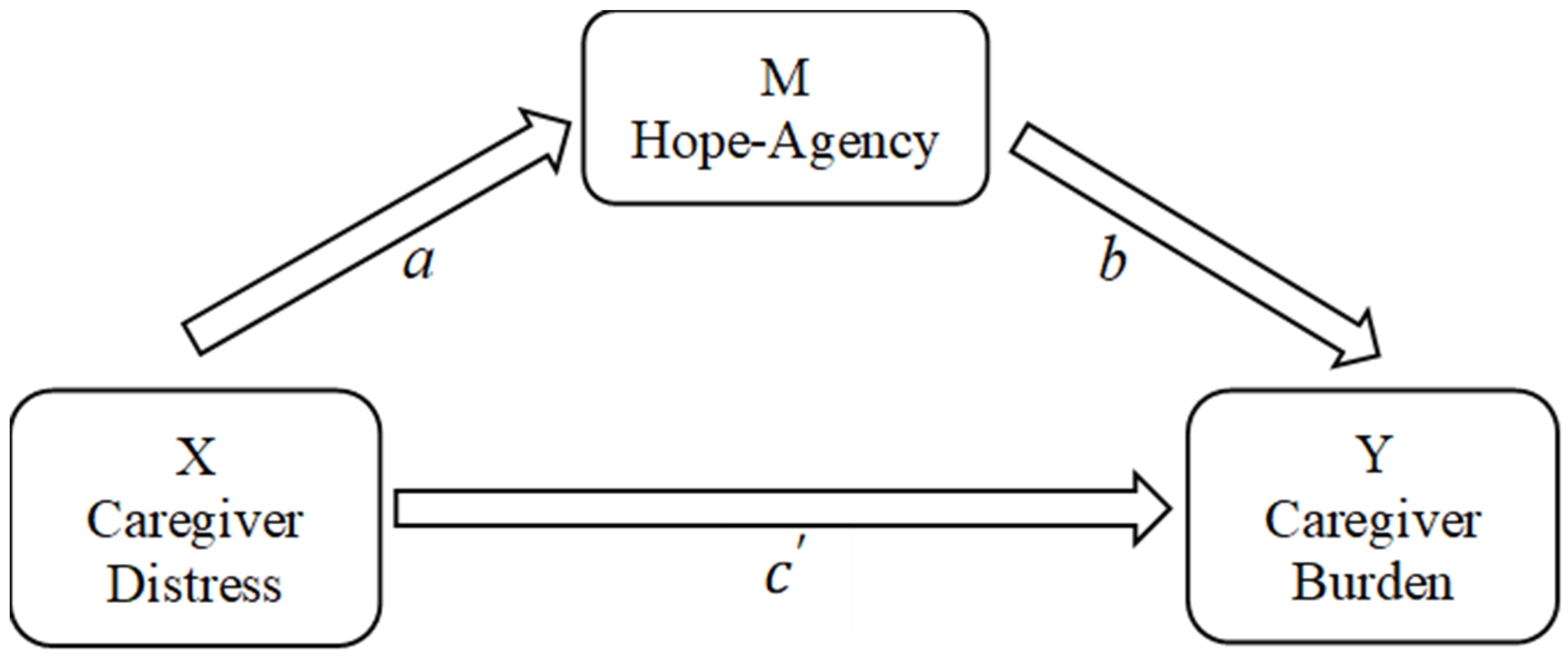

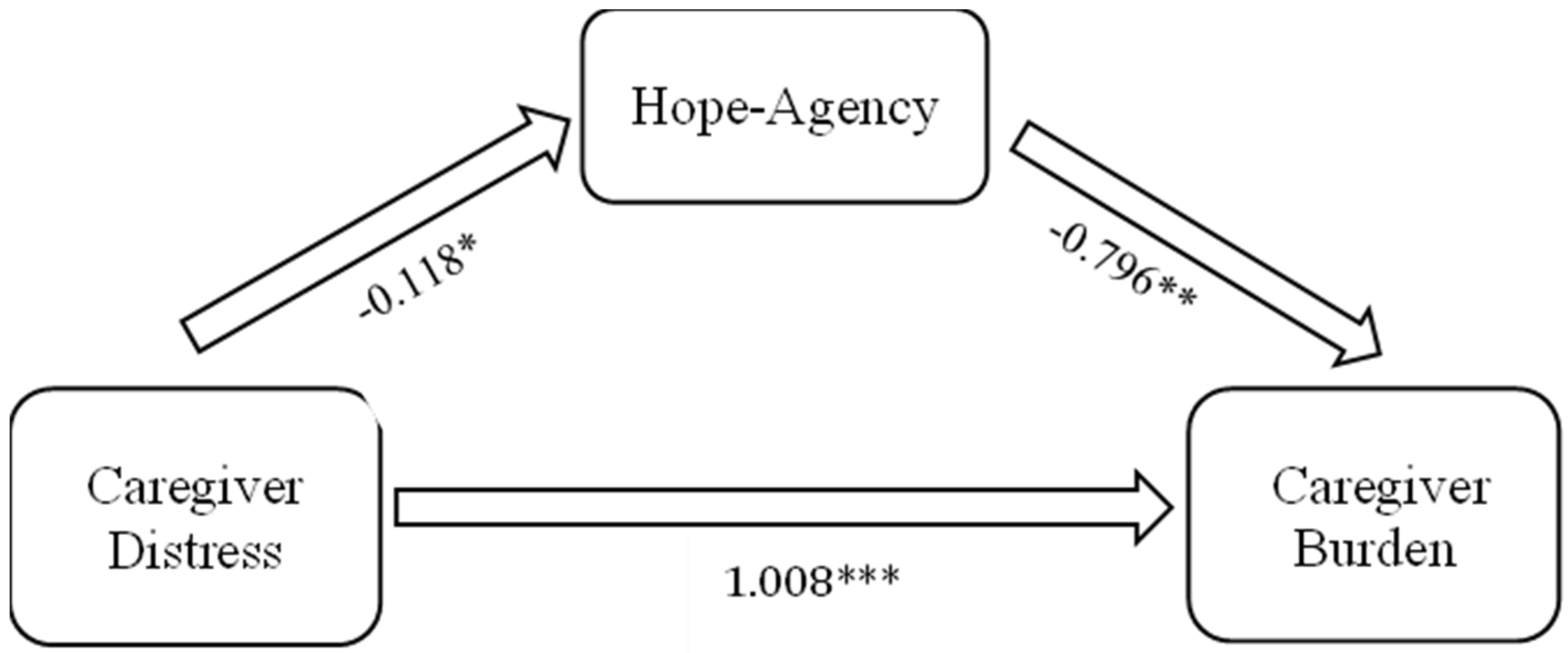

Multiple linear regression models were used to estimate the paths of

a,

b, and

c′ as seen in

Figure 1. The direct effect of subjective stress on burden is indicated by

c′. The indirect effect (mediation) of subjective stress on burden through hope-agency is indicated by

ab. Results, which are reported in

Figure 2, revealed that the direct effect of subjective stress on burden is

c′ = 1.008, while the indirect effect, mediated through hope-agency, is

ab = (-0.118)(-0.796) = 0.094. The indirect effect accounts for 8.53% of the total effect and represents a partial mediation.

Since the Sobel test is conservative (MacKinnon et al., 1995), an increasingly popular method of testing the indirect effect is bootstrapping (Shrout & Bolger, 2002). To further investigate the mediator, the bootstrapping method was utilized to examine whether hope-agency significantly mediated the effect of subjective stress on burden. The results showed that the 95% confidence interval of the indirect effect is (0.0094, 0.2324). Given that zero was not included in the interval, the indirect effect was statistically significant. Therefore, the mediation effect held. There was no evidence of a moderation effect.

7. Discussion

In the current study, we examined the relationships between caregiver burden, two dimensions of hope (i.e., hope-agency, hope-pathway), subjective caregiver stress, and primary and secondary caregiver stressors. The findings of this study confirmed that the two dimensions of hope operate as independent resources in family caregivers of persons with dementia. Among the individuals in our sample, hope-agency and hope-pathway were highly intercorrelated, but not colinear, suggesting that both hope dimensions may be present and should be attended to when working with caregivers of persons with dementia. Moreover, both hope measures were independently and inversely correlated with burden among caregivers while hope-agency produced the higher-level inverse effect.

In essence, caregivers who maintained a sense of confidence or self-efficacy in their ability to carry out their goal (hope-agency) as well as flexibility in problem solving and following the steps needed to achieve their goal (hope-pathway) experienced less burden than those who did not. Caregivers reporting higher levels of agency also indicated the capacity to find ways that supported their aspirations, possibly indicating the capacity of the agentic mindset to encourage wayfinding. The synergy between hope-agency and hope-pathway supports Snyder’s proposition around the agency and pathway interrelationship (Snyder, et al., 2000). Our finding of a significant hope-agency and hope-pathway correlation provides some confirmation of this proposition. This pattern has also been found in non-caregiver samples (Boyce & Harris, 2013; Geraghty et al., 2010). Given these observations, interventions that promote agentic thinking and inform wayfinding may empower caregiver hopefulness and reduce the deleterious effects of burden.

Second, results from multivariate analyses of the relationship between burden and the two dimensions of hope revealed that hope-agency continued to significantly predict caregiver burden, even when controlling for other stressors and social support. In contrast, even though hope-pathway was moderately correlated with caregiver burden, it did not significantly contribute to explaining burden once other stressors and resources, such as social support, were controlled for. While hope-pathway or wayfinding was an important corelate of burden among caregivers in this sample, its effect was largely eclipsed by other important stress process variables.

Based on a recent qualitative study, the dimensions of hope may be understood as individual character strengths that were present before caregiving and also as dynamic states of mind that fluctuate depending on what a caregiver encounters each day (Author at al., 2023a). Therefore, people who are naturally more hopeful may have an affinity for facing some of the realities of providing care for a loved one with dementia. Given the long-term and unpredictable nature of caregiving, however, any caregiver can become less hopeful and experience burden.

It is also noteworthy, that in the current sample, we observed that caregivers who self-identified as female and viewed their situation as distressing or stressful, were more likely to experience burden than caregivers who self-identified as male. Although this gender effect did not hold when hope-agency was taken into consideration, female caregivers may benefit from receiving additional support to build their sense of self-efficacy or agency in this role.

Finally, perhaps the most salient finding from this study is that hope-agency was a partial mediator between subjective stress and burden in this sample of caregivers. Since hope pathway is modifiable, based on our study findings, it is possible that increasing levels of hope may have a positive impact on burden. Our findings confirmed a recent study documenting the mediation role of hope in mitigating burden among family caregivers who were experiencing subjective stress (García-Castro et al., 2019).

8. Implications and Recommendations

Although there are no specific interventions available to date aimed at impacting caregiver hope-agency and hope-pathway, recommendations are provided from evidence-based interventions with other populations that hold promise as worthy candidates for clinical trials that test their efficacy and utility in hope enrichment (Bassett et al., 2008).

8.1. Hope-Focused Caregiver Interventions

A primary implication of this study for professionals is that using hope-building and hope-sustaining assessment and interventions may be effective approaches for reducing the impacts of burden. While not specifically designed for caregivers of persons living with dementia, there are numerous hope-focused resources and interventions designed for other populations (see Snyder’s Handbook of Hope, 2000) that may have relevance for professionals and researchers interested in using hope-focused interventions for caregivers.

Additionally, the Oxford Handbook of Hope (Gallagher & Lopez, 2018) provides a comprehensive review of literature and research on conceptual frames and current hope-focused interventions. It critically examines prior applications in addition to discussing the latest hope intervention studies. More recently, one systematic review of hope interventions (Salamanca-Balen et al., 2021) identified thirty hope related intervention studies involving palliative care patients which may also be relevant for caregivers of persons with dementia.

Weingarten (2010) delivers a noteworthy hope-focused intervention for persons and families experiencing trauma, which we believe has applicability to caregivers of persons living with a dementia. This author offers the idea of reasonable hope, focusing professionals on goals and expectations that are, in the perception of the caregiver, attainable. Reasonable hope is… “consistent with the meaning of the modifier, suggests something both sensible and moderate, directing our attention to what is within our reach more than what may be desired but unattainable.” (2010, p.7) This model offers a rare prescriptive for hope-enrichment work.

We surmise that reasonable hope is more than a positive feeling. It is a present-centered practice focusing on dealing with what is currently available as a path for what the future brings. Rather than filling the time between the present and a possible outcome with anticipation, caregivers can attend to sense-making in the present rather than focus on an unknown future. Hope as a noun can be understood as a quantity, something that individuals possess to varying degrees; whereas hope as verb is an ongoing interior process that a person can engage in. In this approach, professionals accompany caregivers in their hope-challenged appraisals of the future and lostness in finding paths that lead to reasonable hope. Reasonable hope finding is a together act.

8.2. Caregiver Interventions That Indirectly Promote Hope

Psychoeducational and psychotherapeutic interventions to mitigate caregiver burden and impact other outcomes correlated with hope may also energize hope-agency and hope-pathway. In a systematic review, Cheng et al. (2019) identified an expanding array of interventions focused on reducing burden and improving caregiver well-being, including group psychoeducation, individual and family counseling and psychotherapy, multicomponent (individual psychoeducation and psychotherapeutic interventions) interventions. A few examples are Coping with Caregiving (Gallagher-Thompson et. al., 2000); Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) with individual caregivers, intimate partners, and families (Gaugler et al., 2015); and REACH II (Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health; Cheng et al., 2019). There are also telehealth, video, and internet asynchronous and synchronous delivery platforms (Boots et al., 2014) such as Tele-Savvy Caregiver (Hepburn et al., 2022). All these multicomponent interventions could possibly benefit from the integration of a brief hope-focused supplemental intervention caregivers identified as having low hope-agency.

Advocacy and Care Navigation. Case management and advocacy are macro-level interventions that address access to care, structural racism, and economic justice issues that may increase burden and impact caregiver hope. Effective dementia care management support may provide caregivers alternative pathways in dealing with the complexities of access to and engagement with the community health and human services continuum. Having this level of professional expertise and advocacy may empower caregivers with tangible support that energizes hope-agency and removes barriers to hope-driven wayfinding.

8.3. Future Research on Caregiver Hope and Burden Is Needed

Caregiver burden can be reduced or mitigated in the context of a viable sense of hope agency and available pathways. The empirical analyses conducted in this study affirm this contention but do not clarify how caregivers formulate agency (their vision of a desirable future) or how they discern pathways toward this future given the vicissitudes and uncertainties associated with dementia caregiving. In-depth, qualitative studies are needed to specify how hope-agency and hope-pathway find expression as they enact the caregiver role.

Refinements in research design, data gathering strategies, and sampling considerations will improve understanding of the caregiver hope and burden relationship. Clarification of feedback loops among burden correlates, caregiver hope dimensions, and caregiver burden will enlighten understanding of the interactive processes at play as caregivers negotiate caregiving in the context of the ever-changing context of disease progression in dementia.

9. Limitations

This convenience sample was limited to caregivers living within a private home in community settings, usually residing with their loved one with dementia in a large metropolitan area of the U.S. Effective future research and interventions aimed at activating the benefits of hopefulness for mitigating caregiver burden will require more finessed understandings of caregiver’s cultural, ethnic, and/or religious/spiritual beliefs and practices (Smith & Harkness, 2002). Longitudinal studies will serve towards validating the extent to which “preexisting” dispositional caregiver hope directly impacts burden outcomes and the directionality of these relationships.

In addition to adopting a trait hope assumption, this research did not account for the notion of hope variability within life domains (relational, academic, work, and leisure) as proposed by Sympson (1999). Rather than assume that caregivers’ level of hope-agency and hope-pathway were based on the challenges of caregiving, it is also important to better understand the intersectionality of the caregiving role with other life domains.

10. Conclusion

There are noteworthy contributions from this study of the relationship between stress, hope, and burden among family caregivers of persons with dementia. Caregivers may be engaged in a continuous future-oriented, cognitive appraisal process, involving a reciprocal and additive exchange between hope-agency ends and hope-pathway means. There is evidence that caregiver hope is individual and dispositional but also modifiable based on learning new responses to continuous feedback along the temporal pathway experience.

Hope-agency, in this study, was a mediator of the relationship between subjective caregiver stress and the extent of perceived burden. These findings affirm a recent study (García-Castro et al., 2020) on the explanatory power of hope for predicting caregiver burden while being among the first to conceptually center our measurement approach within the widely applied and validated Snyder (1991) concept of hope measure dimensionality.

We offer applied implications of our findings intended to inform researchers and professionals seeking to reduce caregiver burden by testing interventions intended to realistically strengthen caregiver sustainment of confidence in future possibilities (hope-agency) and to identify viable processes and pathways for movement toward these possibilities (hope-pathway).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.S.M., D.M., E.C.P.; Methodology, J.S.M., D.M., E.C.P.; Formal Analysis, W.K., E.C.P.; Investigation, J.S.M., H.C.Z.; Resources, J.S.M.; Data Curation, J.S.M., H.C.Z.; Writing—original draft preparation, A.M., J.S.M., D.M., E.C.P.; Writing—review and editing, R.M., A.M., J.S.M., D.M., E.C.P., H.C.Z.; Supervision, J.S.M.; Project Administration, J.S.M.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Baylor University (protocol code #346183-1) and Baylor College of Medicine (protocol code #H27755).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are not publicly available for the purposes of privacy and confidentiality of research participants.

Acknowledgments

At the time of data collection, Dr. Jocelyn McGee was on faculty at the Alzheimer’s Disease and Memory Disorders Center at Baylor College of Medicine. We wish to express appreciation for the resources that Baylor College of Medicine and Baylor University contributed to make this study possible. Additionally, we are grateful to Amazing Place in Houston and the Alzheimer’s Association for their assistance in recruitment. Thank you to Brittany Kuka Phillips for your work on data entry and to all of the research associates who made this study possible. Most importantly, however, is our sincere gratitude for the family caregivers who participated in this study. Your lives and the lives of your loved ones with Alzheimer’s disease or another related dementia has made a difference for so many through your participation in this study. Thank you for sharing your lived experiences and journey with us.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Adams, K. (2008). Specific effects of caring for a spouse with dementia: Differences in depressive symptoms between caregiver and non-caregiver spouses. International Psychogeriatrics, 20(3), 508-520. [CrossRef]

- Alzheimer’s Association. 2023 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimer’s Dement 2023;19(4). [CrossRef]

- Arbel, I., Bingham, K. S., & Dawson, D. R. (2019). A scoping review of literature on sex and gender differences among dementia spousal caregivers. The Gerontologist, 59(6), e802-e815. [CrossRef]

- Author, et al (2019).

- Author, et al. (2022a).

- Author, et al. (2022b).

- Author, et al. (2023).

- Bailey, T. C., Eng, W., Frisch, M. B., & Snyder, C. R. (2007). Hope and optimism as related to life satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 2(3), 168-175. [CrossRef]

- Bassett, H., Lloyd, C., & Tse, S. (2008). Approaching in the right spirit: Spirituality and hope in recovery from mental health problems. International Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation, 15(6), 253-261. [CrossRef]

- Beach, S. R., & Shulz, R. (2017). Family caregiver factors associated with unmet needs for care of older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 65(3), 560-566. [CrossRef]

- Beach, S. R., Schulz, R., Williamson, G. M., Miller, L. S., Weiner, M. F., & Lance, C. E. (2005). Risk factors for potentially harmful informal caregiver behavior. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 53(2), 255-261. [CrossRef]

- Boots, L. M. M., de Vugt, M. E., Van Knippenberg, R. J. M., Kempen, G. I. J. M., & Verhey, F. R. (2014). A systematic review of Internet-based supportive interventions for caregivers of patients with dementia. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 29(4), 331-344. [CrossRef]

- Boyce, G., & Harris, G. (2013). Hope the beloved country: Hope levels in the new South Africa. Social Indicators Research, 113(1), 583-597. [CrossRef]

- Chappell, N. L., Dujela, C., & Smith, A. (2015). Caregiver well-being: Intersections of relationship and gender. Research on Aging, 37(6), 623-645. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S., Au, A., Losado, A., Thompson, L.W., & Gallagher-Thompson, D. (2019). Psychological interventions for dementia caregivers: What we have achieved, what we have learned. Current Psychiatry Reports, 21(7), 59-12. [CrossRef]

- Collins, R. N., & Kishita, N. (2019). Prevalence of depression and burden among informal care-givers of people with dementia: A meta-analysis. Ageing & Society, 40(11), 2355-2392. [CrossRef]

- Cummings, J. L., Mega, M., Gray, K., Rosenberg-Thompson, S., Carusi, D.A., & Gornbein, J. (1994). The neuropsychiatric inventory: Comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology, 44, 23–14. [CrossRef]

- Del-Pino-Casado, R., Frías-Osuna, A., Palomino-Moral, P.A., Ruzafa-Martínez, M., Ramos-Morcillo, A.J. (2018) Social support and subjective burden in caregivers of adults and older adults: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 13(1): e0189874. [CrossRef]

- DiGasbarro, D., Van Haitsma, K., Meeks, S., & Mast, B. T. (2019). Optimism, quality of life, and cognition in recent nursing home residents. Innovation in Aging, 3(Suppl 1), S113. [CrossRef]

- Duggleby, W., Williams, A., Wright, K., & Bollinger, S. (2009). Renewing everyday hope: The hope experience of family caregivers of persons with dementia. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 30(8), 514-521. [CrossRef]

- Drach-Zahavy, A., & Somech, A. (2002). Coping with health problems: the distinctive relationships of Hope sub-scales with constructive thinking and resource allocation. Personality and Individual Differences, 33(1), 103–117. [CrossRef]

- Gallagher-Thompson, D., Arean, P., Coon, D., Menendez, A., Takagi. K., Haley, W.,…& Szapocznik, J. (2000). Development and implementation of intervention strategies for culturally diverse caregiving populations. Handbook on dementia caregiving: Evidence-based interventions for family caregivers, 151-185.

- Gallagher, M. W., & Lopez, S.J. (2018). The Oxford handbook of hope (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Castro, F. J., Alba, A., & Blanca. M. J. (2019). The role of character strengths in predicting gains in informal caregivers of dementia. Aging and Mental Health, 25, 32-37. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Castro, F. J., Alba, A., & Blanca. M. J. (2020). Association between character strengths and caregiver burden: Hope as a mediator. Journal of Happiness Studies, 21(4), 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Gaugler, J. E., Reese, M., & Mittelman, M. B. (2015). Effects of the Minnesota Adaptation of the NYU Caregiver Intervention on depressive symptoms and quality of life for adult child caregivers of persons with dementia. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychology, 23, 1179-1192. [CrossRef]

- Geraghty, A. W. A., Wood, A. M., & Hyland, M. E. (2010). Dissociating the facets of hope: Agency and pathways predict dropout from unguided self-help therapy in opposite directions. Journal of Research in Personality, 44(1), 155-158. [CrossRef]

- Hébert, R., Bravo, G., & Préville, M. (2000). Reliability, validity and reference values of the Zarit Burden Interview for assessing informal caregivers of community-dwelling older persons with dementia. Canadian Journal on Aging, 19(4), 494-507. [CrossRef]

- Hepburn, K., Nocera, J., Higgins, M., Epps. F., Brewster, G. S., Lindauer, A., Morhardt, D., Shah, R. S., Bonds, K., Nash, R., & Griffiths, P. G. (2022). Results of a randomized trial testing of the efficacy on Tele-Saavy, an online synchronous/asynchronous psychoeducation program for family caregivers of persons living with dementia. The Gerontologist, 62(4), 616-628. [CrossRef]

- Herrera, A. P., Lee, J. W., Nanyonjo, R. D., Laufman, L. E., & Torres-Vigil, I. (2009). Religious coping and caregiver well-being in Mexican-American families. Aging & Mental Health, 13(1), 84-91. [CrossRef]

- Kaddour, L., & Kishita, N. (2020). Anxiety in informal dementia carers: A meta-analysis of prevalence. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology, 33(3), 161-172. [CrossRef]

- Kazmer, M. M., Glueckauf, R. L., Schettini, G., Ma, J., & Silva, M. (2018). Qualitative analysis of faith community nurse–led cognitive-behavioral and spiritual counseling for dementia caregivers. Qualitative Health Research, 28(4), 633-647. [CrossRef]

- Kokorelias, K.M., Naglie, G., Gignac, M. A., Rittenberg, N., & Cameron, J. I. (2021). A qualitative exploration of how gender and relationship shape family caregivers’ experiences across the Alzheimer’s disease trajectory. Dementia, 20(8), 2851–2866. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z., Heffernan, C., & Tan, J. (2020). Caregiver burden: A concept analysis. International journal of nursing sciences, 7(4), 438-445. [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, D. P., Warsi, G., & Dwyer, J. H. (1995). A simulation study of mediated effect measures. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 30, 41-62. [CrossRef]

- Pearlin, L. I., & Bierman, A. (2013). Current issues and future directions in research into the stress process. In C. S. Aneshensel, J. C. Phelan, & A. Bierman (Eds.), Handbook of the sociology of mental health. Handbooks of sociology and social research (pp. 325–340). Springer.

- Pearlin, L. I., Mullan, J. T., Semple, S. J., & Skaff, M. M. (1990). Caregiving and the stress process: An overview of concepts and their measures. The Gerontologist, 30(5), 583–594. [CrossRef]

- Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. Oxford University Press.

- Potgieter, J. C., & Heyns, P. M. (2006). Caring for a spouse with Alzheimer’s disease: Stressors and strengths. South African Journal of Psychology, 36(3), 547-563. [CrossRef]

- Quinn, C., Clare, L., & Woods, R. T. (2010). The impact of motivations and meanings on the wellbeing of caregivers of people with dementia: A systematic review. International Psychogeriatrics, 22(1), 43-55. [CrossRef]

- Rajan KB, Weuve J, Barnes LL, McAninch EA, Wilson RS, Evans DA. Population estimate of people with clinical AD and mild cognitive impairment in the United States (2020-2060).Alzheimer’s Dement 2021;17(12):1966-75. [CrossRef]

- Salamanca-Balen, N., Merluzzi, T., & Chen, M. (2021). The effectiveness of hope-fostering interventions in palliative care: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Palliative Medicine, 35(4), 710-728. [CrossRef]

- Schulz, R., Beach, S. R., & Friedman, E. M. (2021). Caregiving factors as predictors of care recipient mortality. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 29(3), 295-303. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrout, P. E., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7, 422-445. [CrossRef]

- Snyder, C. R. (1995). Conceptualizing, measuring, and nurturing hope. Journal of Counseling & Development, 73(3), 355-360. [CrossRef]

- Snyder, C.R. (2000). Handbook of hope: Theory, measures, and applications. Academic Press.

- Snyder, C. R., Harris, C., Anderson, J. R., Holleran, S. A., Irving, L. M., Sigmon, S. T., & Harney, P. (1991). The will and the ways: Development and validation of an individual-differences measure of hope. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(4), 570-585. [CrossRef]

- Sympson, S.C. (1999). Validation of the Domain Specific Hope Scale: Exploring hope in life domains. [Unpublished doctoral dissertation], University of Kansas, Lawrence.

- Thompson, L. W., Spira, A. P., Depp, C. A., McGee, J. S., & Gallagher-Thompson, D. (2005). The Geriatric Caregiver. In Marc E. Agronin & Gabe J. Maletta (Eds.), Principles and Practice of Geriatric Psychiatry (1st Edition). Lippincott, Williams, & Wilkins: Philadelphia. ISBN-10: 0781748100, ISBN-13: 978-0781748100.

- Tsai, C.-F., Hwang, W.-S., Lee, J.-J., Wang, W.-F., Huang, L.-C., Huang, L.-K., Lee, W.-J., Sung, P.-S., Liu, Y-C., Hsu, C.-C., & Fuh, J.-L. (2021). Predictors of caregiver burden in aged caregivers of demented older patients. BMC Geriatrics, 21(1), 59. [CrossRef]

- U.S. Census Bureau data. Available online: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/popest/data/tables.html.

- Weingarten, K. (2010). Reasonable hope: Construct, clinical applications, and supports. Family Process, 49(1), 5-25. [CrossRef]

- Zarit, S.H., Reever, K.E., & Bach-Peterson, J. (1980). Relatives of the impaired elderly: Correlations of feeling of burden. Gerontologist, 20, 649–655. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).