Submitted:

28 December 2023

Posted:

29 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

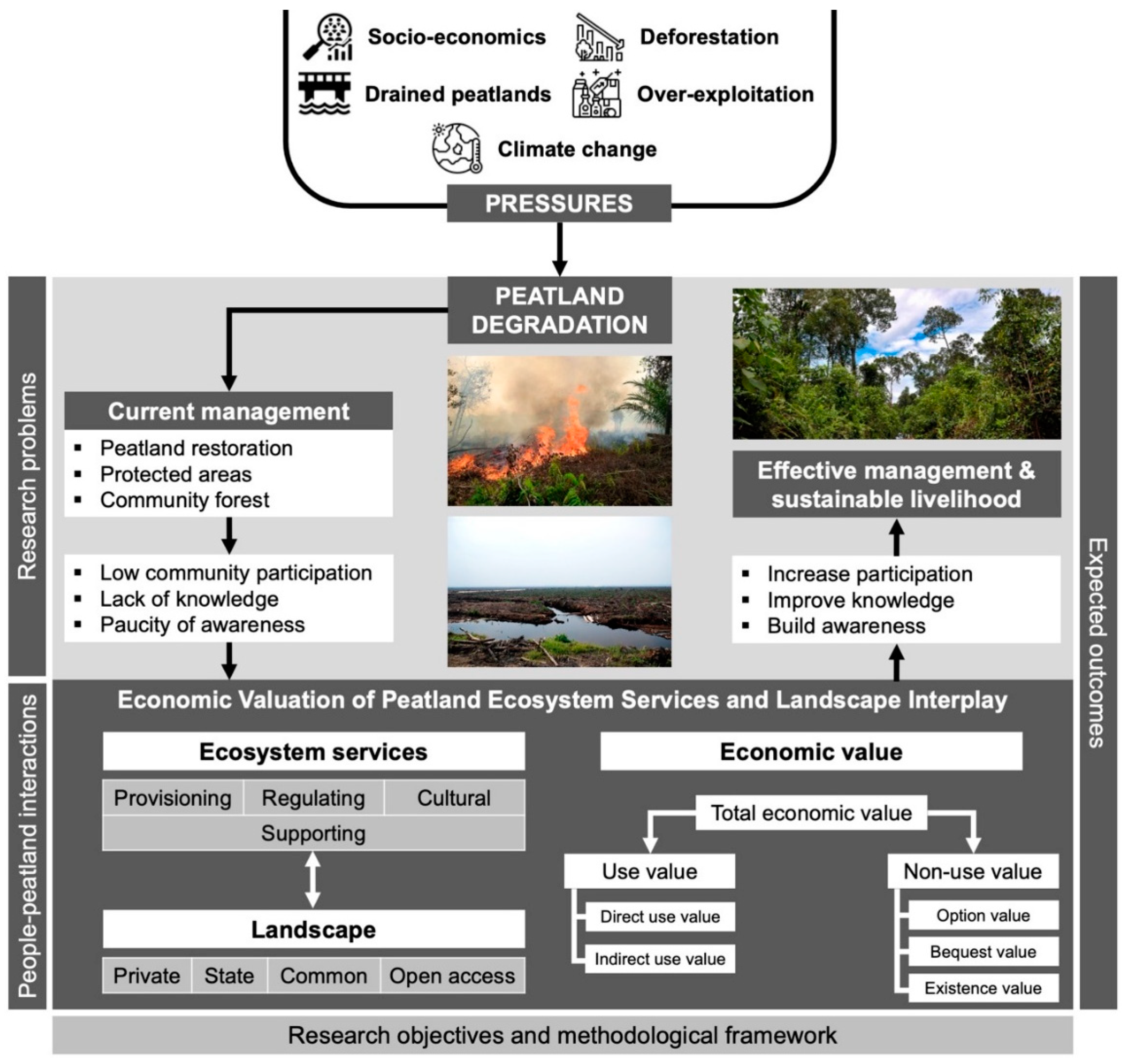

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

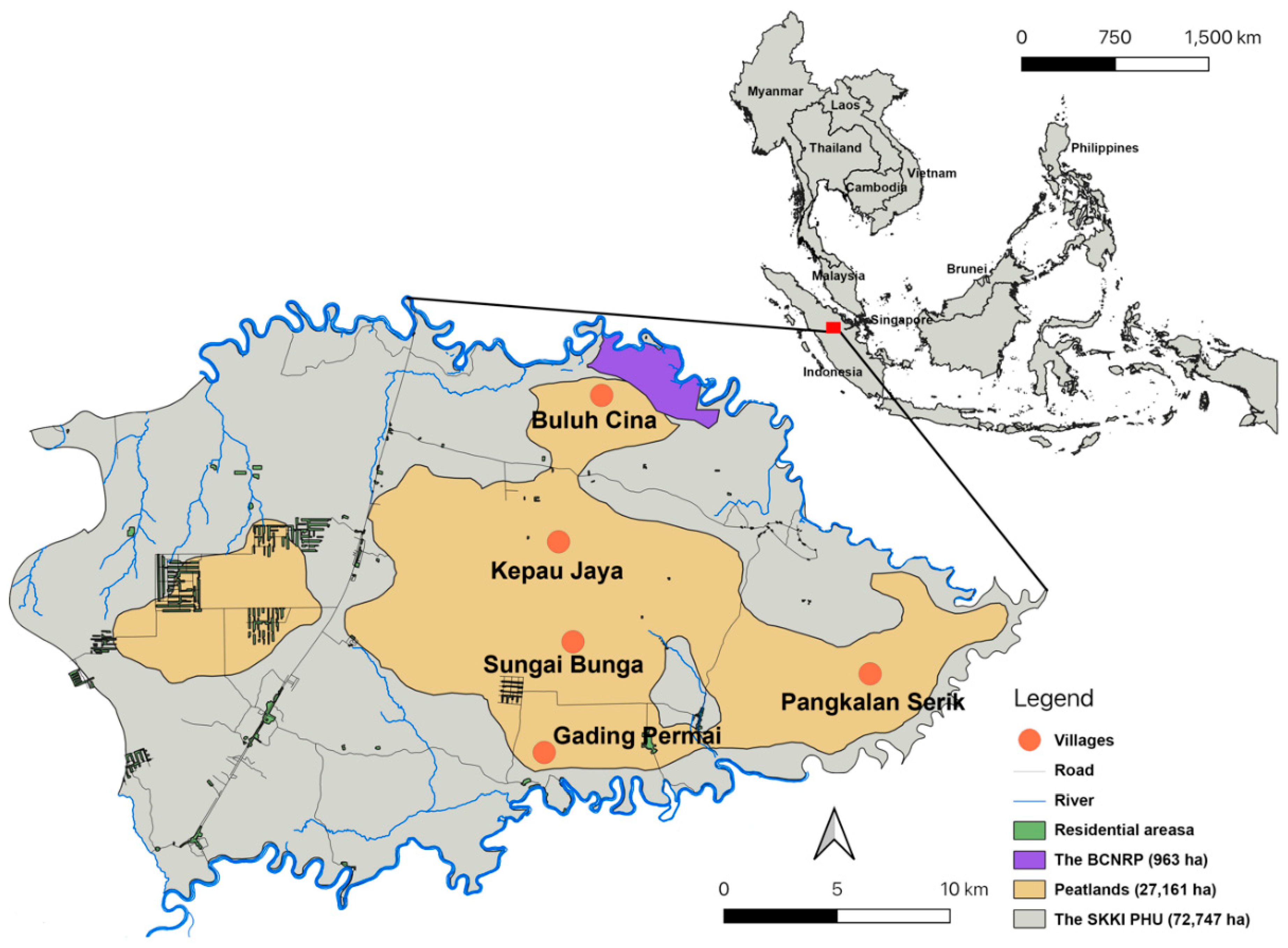

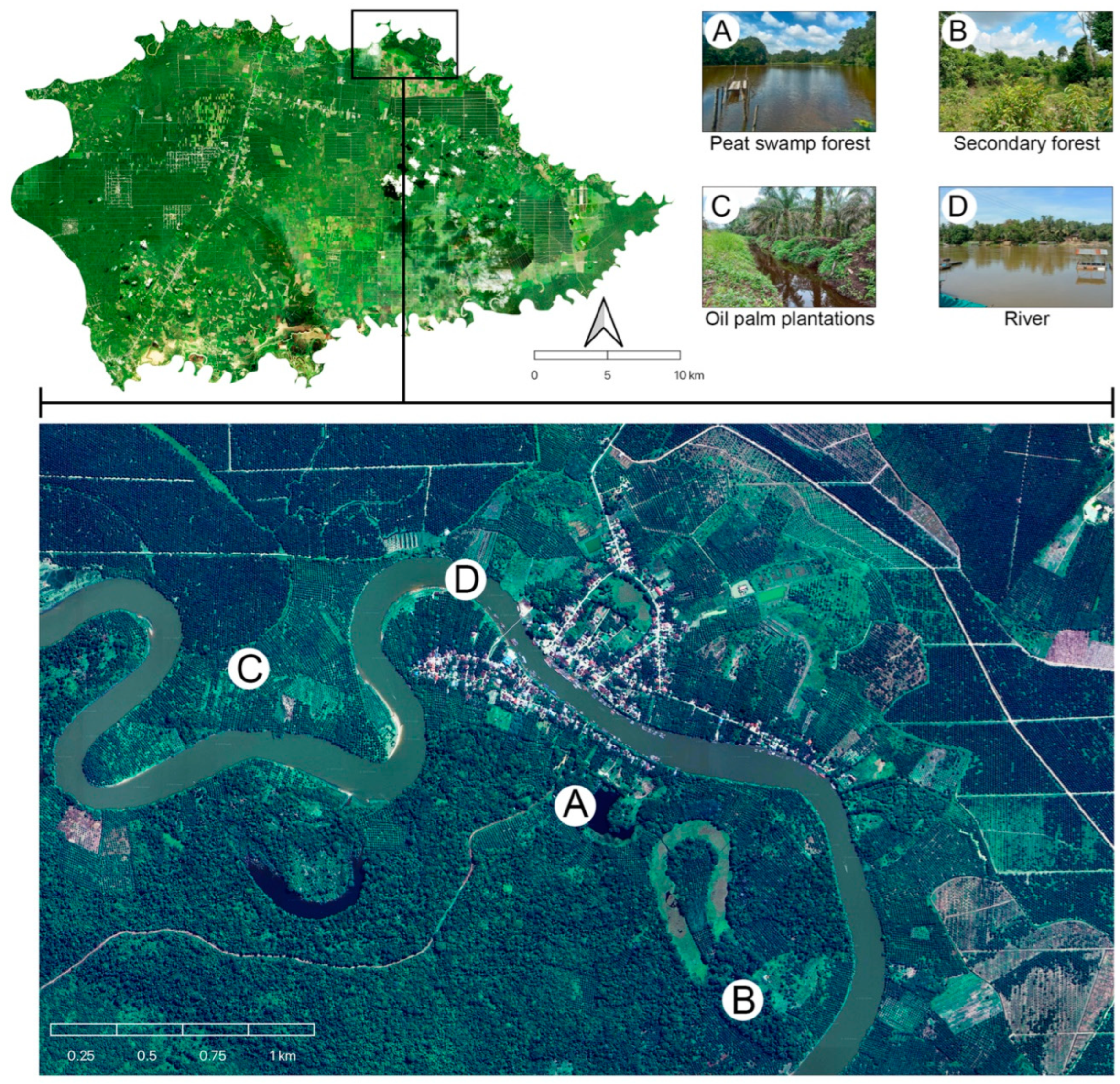

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Scope of the Study

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Measurement of the Total Economic Value of Peatland Ecosystem Services

2.5. Statistical Data Analysis

3. Results

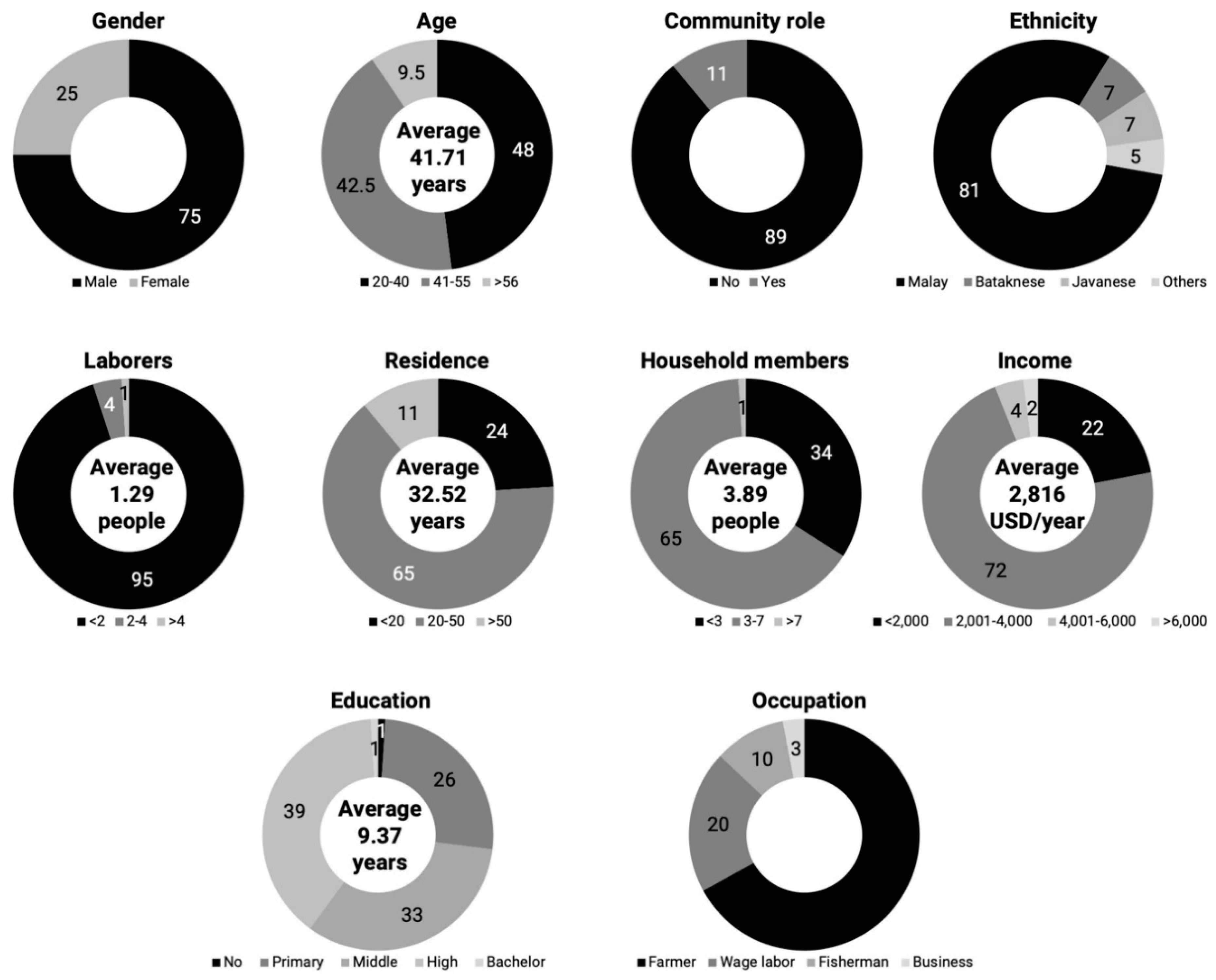

3.1. Household Socio-Economic Conditions and Livelihoods

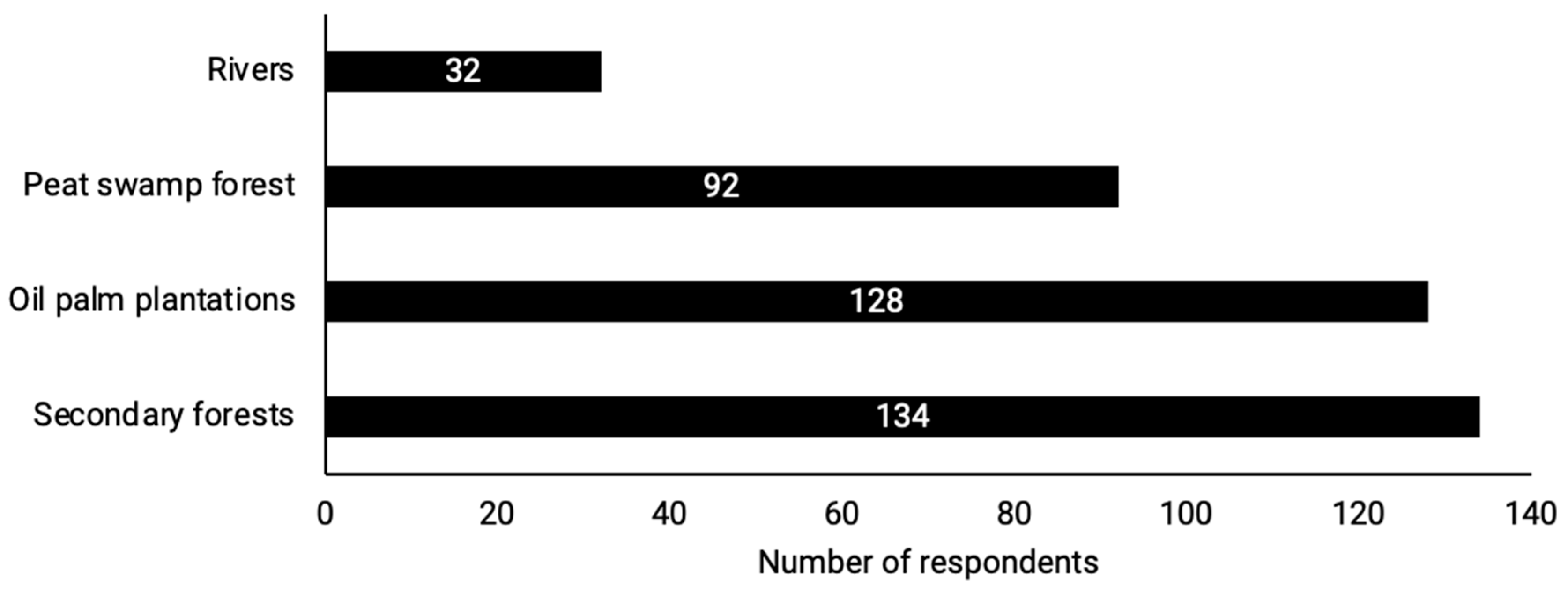

3.2. Access to the Peatland and Product Collection

3.3. Total Economic Value of Peatland Ecosystem Services

3.4. People – Peatland Landscape Interplay: Ecological and Socio-Economic Settings Determining Amounts and Economic Value of Ecosystem Services

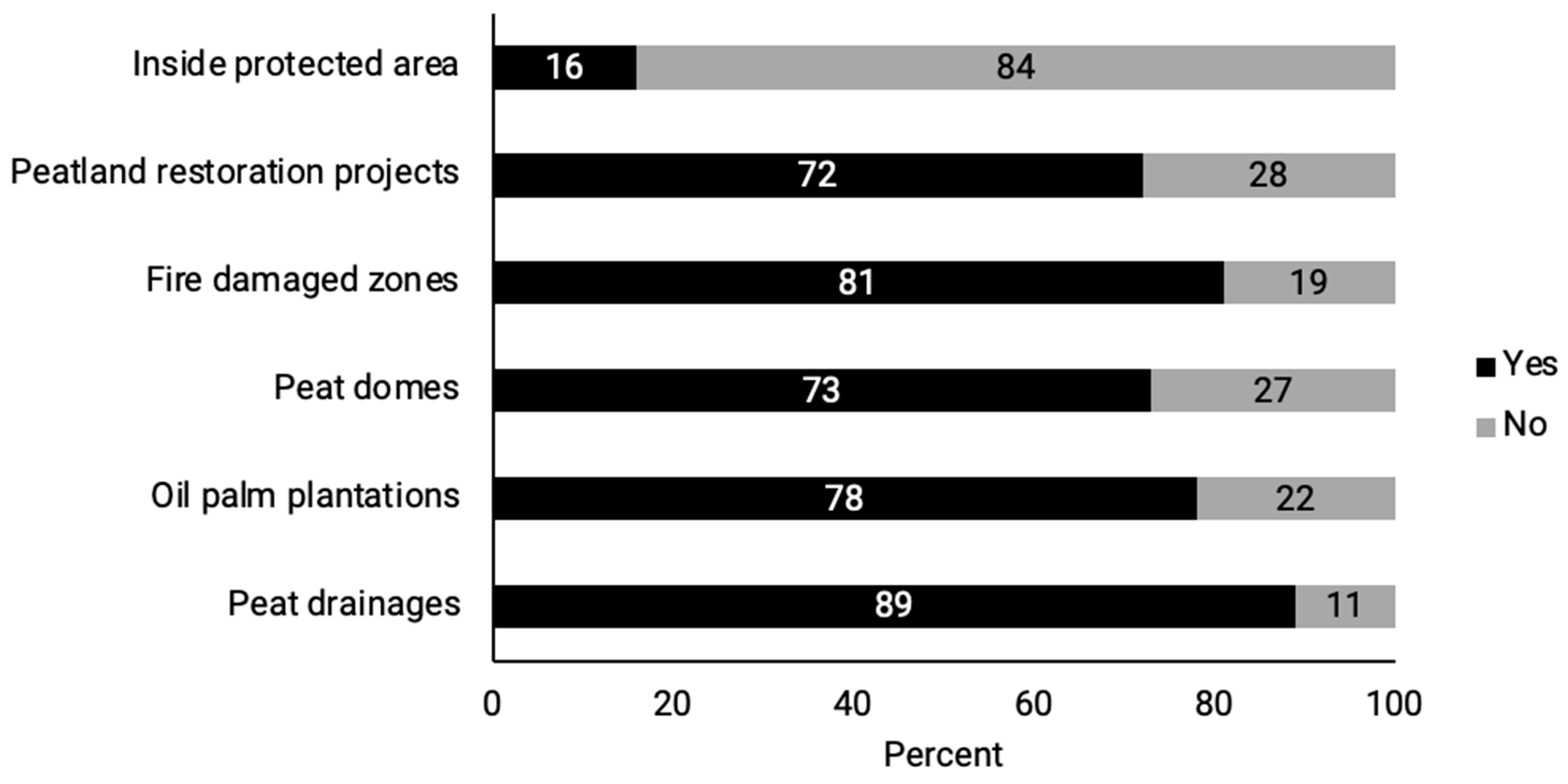

| No. | Landscape condition | Main PPRs | No, I didn’t live inside/near | Yes, l lived inside/near | t | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||||

| 1 | Protected area | S | 2,549.43 | 2,965.07 | 6,454.91 | 2,378.79 | -8.158 | <0.001 |

| 2 | Restoration site | S, C | 4,333.70 | 2,765.48 | 2,723.44 | 3,269.31 | 3.259 | 0.001 |

| 3 | Fire damaged-zones | O | 2,214.21 | 2,639.55 | 3,399.52 | 3,299.34 | -2.064 | 0.040 |

| 4 | Peat domes | S, C | 4,452.89 | 3,386.90 | 2,701.41 | 3,022.59 | 3.520 | <0.001 |

| 5 | Oil palm plantations | P | 3,637.95 | 4,711.55 | 3,043.54 | 2,648.13 | 0.802 | 0.426 |

| 6 | Peat drainages | P | 4,938.32 | 2,329.73 | 2,956.29 | 3,244.05 | 2.776 | 0.006 |

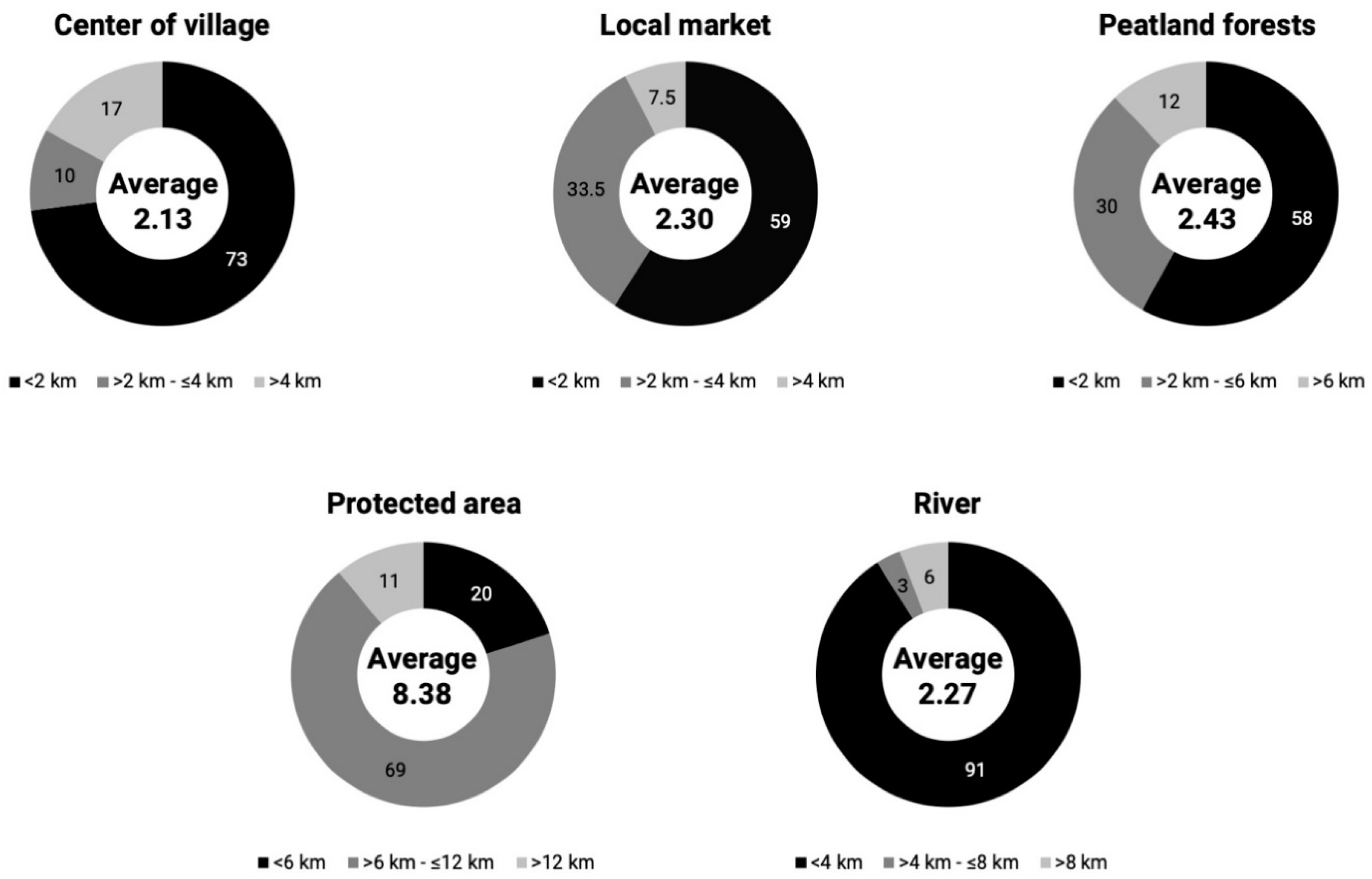

| No. | Variables | TEV | F | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | ||||

| 1 | Center of village | ||||

| Near (0 – 2 km) | 3,576.87a | 3,541.00 | 4.433 | 0.013 | |

| Intermediate (>2 km <4 km) | 1,925.55b | 1,101.69 | |||

| Far (> 4 km) | 2,180.26b | 1,938.53 | |||

| 2 | Local market | ||||

| Near (0 – 2 km) | 3,201.59 | 3,288.55 | 0.012 | 0.988 | |

| Intermediate (>2 km <4 km) | 3,125.18 | 3,348.17 | |||

| Far (> 4 km) | 3,179.18 | 1,855.47 | |||

| 3 | Peatland forests | ||||

| Near (0 – 2 km) | 3,774.70a | 3,855.34 | 5.040 | 0.007 | |

| Intermediate (2.1- 6 km) | 2,300.69b | 1,752.95 | |||

| Far (> 6 km) | 2,456.52b | 1,655.47 | |||

| 4 | Protected area | ||||

| Near (0 – 6 km) | 7,405.62a | 4,038.62 | 76.442 | <0.001 | |

| Intermediate (>6 km <12 km) | 2,162.75b | 1,875.79 | |||

| Far (> 12 km) | 1,826.30b | 1,347.37 | |||

| 5 | River | ||||

| Near (0 – 4 km) | 3,324.80 | 3,309.25 | 2.669 | 0.072 | |

| Intermediate (>4 km <8 km) | 2,617.87 | 840.40 | |||

| Far (> 8 km) | 1,170.10 | 1,118.11 | |||

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bonn, A.; Allott, T.; Evans, M.; Joosten, H.; Stoneman, R. Peatland Restoration and Ecosystem Services: An Introduction. In Peatland Restoration and Ecosystem Services: Science, Policy and Practice; Bonn, A., Joosten, H., Evans, M., Stoneman, R., Allott, T., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2016; pp. 1–16. ISBN 978-1-107-61970-8. [Google Scholar]

- Joosten, H.; Clarke, D. Wise Use of Mires and Peatlands: Background and Principles Including a Framework for Decision-Making; International Mire Conservation Group and International Peat Society: Saarijärvi, Finland, 2002; ISBN 951-97744-8-3. [Google Scholar]

- Wichmann, S.; Brander, L.; Schäfer, A.; Schaafsma, M.; Van Beukering, P.; Tinch, D.; Bonn, A. Valuing Peatland Ecosystem Services. In Peatland Restoration and Ecosystem Services: Science, Policy and Practice; Cambridge University Press, 2016; pp. 314–338. ISBN 978-1-139-17778-8. [Google Scholar]

- Anda, M.; Ritung, S.; Suryani, E.; Sukarman; Hikmat, M.; Yatno, E.; Mulyani, A.; Subandiono, R.E.; Suratman; Husnain. Revisiting Tropical Peatlands in Indonesia: Semi-Detailed Mapping, Extent and Depth Distribution Assessment. Geoderma 2021, 402, 115235–115235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawan, H. Indonesian Peatland Functions: Initiated Peatland Restoration and Responsible Management of Peatland for the Benefit of Local Community, Case Study in Riau and West Kalimantan Provinces. In Asia in Transition; Springer, 2018; Vol. 7, pp. 117–138. [CrossRef]

- Syahza, A.; Suwondo; Bakce, D. ; Nasrul, B.; Mustofa, R. Utilization of Peatlands Based on Local Wisdom and Community Welfare in Riau Province, Indonesia. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2020, 15, 1119–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieminen, M.; Sarkkola, S.; Laurén, A. Impacts of Forest Harvesting on Nutrient, Sediment and Dissolved Organic Carbon Exports from Drained Peatlands: A Literature Review, Synthesis and Suggestions for the Future. For. Ecol. Manag. 2017, 392, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parish, F.; Sirin, A.; Charman, D.; Joosten, H.; Minayeva, T.; Silvius, M.; Stringer, L. Assessment on Peatlands, Biodiversity, and Climate Change: Main Report; Global Environment Centre and Wetlands International: Kuala Lumpur and Wageningen, 2008. ISBN 978-983-43751-0-2.

- Li, C.; Grayson, R.; Holden, J.; Li, P. Erosion in Peatlands: Recent Research Progress and Future Directions. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2018, 185, 870–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatano, R. Impact of Land Use Change on Greenhouse Gases Emissions in Peatland: A Review. Int. Agrophysics 2019, 33, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, L.; Ge, Z.; Zhou, X.; Li, S.; Li, X.; Tang, J. Conversion of Coastal Wetlands, Riparian Wetlands, and Peatlands Increases Greenhouse Gas Emissions: A Global Meta-Analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 26, 1638–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohong, A.; Aziz, A.A.; Dargusch, P. A Review of the Drivers of Tropical Peatland Degradation in South-East Asia. Land Use Policy 2017, 69, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medrilzam, M.; Dargusch, P.; Herbohn, J.; Smith, C. The Socio-Ecological Drivers of Forest Degradation in Part of the Tropical Peatlands of Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. For. Int. J. For. Res. 2014, 87, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medrilzam, M.; Smith, C.; Aziz, A.A.; Herbohn, J.; Dargusch, P. Smallholder Farmers and the Dynamics of Degradation of Peatland Ecosystems in Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 136, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuno, K.; Masuda, K.; Syahza, A. Peatland Degradation, Timber Plantations, and Land Titles in Sumatra. In Vulnerability and Transformation of Indonesian Peatlands; Mizuno, K., Kozan, O., Gunawan, H., Eds.; Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd: Gateway East, Singapore, 2023; Vol. 1, pp. 17–49. [Google Scholar]

- Miettinen, J.; Shi, C.; Liew, S.C. Land Cover Distribution in the Peatlands of Peninsular Malaysia, Sumatra and Borneo in 2015 with Changes since 1990. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2016, 6, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Environmental and Forestry Republic of Indonesia Luas Karhutla. SiPongi Karhutla Monit. Syst. 2023.

- Huijnen, V.; Wooster, M.J.; Kaiser, J.W.; Gaveau, D.L.A.; Flemming, J.; Parrington, M.; Inness, A.; Murdiyarso, D.; Main, B.; van Weele, M. Fire Carbon Emissions over Maritime Southeast Asia in 2015 Largest since 1997. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 26886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiely, L.; Spracklen, D.V.; Wiedinmyer, C.; Conibear, L.; Reddington, C.L.; Arnold, S.R.; Knote, C.; Khan, M.F.; Latif, M.T.; Syaufina, L.; et al. Air Quality and Health Impacts of Vegetation and Peat Fires in Equatorial Asia during 2004–2015. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 094054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hein, L.; Spadaro, J.V.; Ostro, B.; Hammer, M.; Sumarga, E.; Salmayenti, R.; Boer, R.; Tata, H.; Atmoko, D.; Castañeda, J.-P. The Health Impacts of Indonesian Peatland Fires. Environ. Health 2022, 21, 62–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uda, S.K.; Hein, L.; Atmoko, D. Assessing the Health Impacts of Peatland Fires: A Case Study for Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 31315–31327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Environmental and Forestry Republic of Indonesia Protection and Management of Peat Ecosystems.

- Peatland and Mangrove Restoration Agency Laporan Kinerja 2021 (2021 Performance Report); Jakarta, 2022; pp. 1–88.

- Kristiadi Harun, M.; Tri, A.; Yuwati, W. Agroforesty System For Rehabilitation of Degraded Peatland in Central Kalimantan. J. Wetl. Environ. Manag. 2015, 3, 41–46. [Google Scholar]

- Budiman, I.; Bastoni; Sari, E. N.; Hadi, E.E.; Asmaliyah; Siahaan, H.; Januar, R.; Hapsari, R.D. Progress of Paludiculture Projects in Supporting Peatland Ecosystem Restoration in Indonesia. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 23, e01084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawan, H.; Afriyanti, D.; Dewanto, H.A. Show Windows and Lessons Learned from Peatland Restoration in Indonesia. In Tropical Peatland Eco-management; Osaki Mitsuru and Tsuji, N. and F.N. and R.J., Ed.; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2021; pp. 751–774. ISBN 978-981-334-654-3. [CrossRef]

- Ward, C.; Warren-Thomas, E.; Agus, F.; Crowson, M.; Hamer, K.; Hariyadi, B.; Kartika, W.D.; Lucey, J.; McClean, C.; Nurida, N.L.; et al. Smallholder Perceptions of Land Restoration Activities: Rewetting Tropical Peatland Oil Palm Areas in Sumatra, Indonesia. Reg. Environ. Change 2020, 21, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, C.; Stringer, L.C.; Warren-Thomas, E.; Agus, F.; Hamer, K.; Pettorelli, N.; Hariyadi, B.; Hodgson, J.; Kartika, W.D.; Lucey, J.; et al. Wading through the Swamp: What Does Tropical Peatland Restoration Mean to National-Level Stakeholders in Indonesia? Restor. Ecol. 2020, 28, 817–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristiansen, S.; Budiman, A.; Pudyatmoko, S. Ecosystem Guardians or Threats? Livelihood Security and Nature Conservation in Maluku, Indonesia. Bull. Indones. Econ. Stud. 2023, 59, 119–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagdee, A.; Kim, Y.; Daugherty, P.J. What Makes Community Forest Management Successful: A Meta-Study From Community Forests Throughout the World. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2006, 19, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shumba, T.; De Vos, A.; Biggs, R.; Esler, K.J.; Clements, H.S. The Influence of Biophysical and Socio-Economic Factors on the Effectiveness of Private Land Conservation Areas in Preventing Natural Land Cover Loss across South Africa. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2021, 28, e01670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Jiao, W. Conservation-Compatible Livelihoods: An Approach to Rural Development in Protected Areas of Developing Countries. Environ. Dev. 2023, 45, 100797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. A General Framework for Analyzing Sustainability of Social-Ecological Systems. Science 2009, 325, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. A Report of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being; Island Press: Washington DC, 2005; p. 137. ISBN 1-59726-040-1. [Google Scholar]

- Central Bureau of Statistics of Kampar Regency Kampar Regency in Figures; Bangkinang, 2022; pp. 1–254.

- BBKSDA Riau Taman Wisata Buluh Cina. Available online: https://bbksdariau.id/index.php?r=post&id01=4&id02=23&id03=52&token=529721b182f5ef92394ea00539e3f745 (accessed on 25 August 2023).

- Sukma, D.; Hadinoto, H.; Suhesti, E. IDENTIFIKASI POTENSI DAN DAYA TARIK WISATA KHDTK BULUH CINA KABUPATEN KAMPAR PROVINSI RIAU. Wahana For. J. Kehutan. 2022, 17, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efizon, D.; Putra, R.M.; Kurnia, F.; Yani, A.H.; Fauzi, M. KEANEKARAGAMAN JENIS-JENIS IKAN DI OXBOW PINANG DALAM DESA BULUH CINAKABUPATEN KAMPAR, RIAU. In Proceedings of the Ekologi, Habitat Manusia dan Perubahan Persekitaran; Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia: Kedah, 2015.

- Alpino; Yoza, D.; Mardhiansyah, M. Diversity and Potential of Rattan in Buluh Cina Nature Tourism Park Buluh Cina Village Kampar District. J. Ilmu-Ilmu Kehutan. 2020, 4, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istiqfar, S.; Yoza, D.; Sulaeman, R. KEANEKARAGAMAN JENIS TUMBUHAN OBAT DI HUTAN ADAT RIMBO TUJUH DANAU DESA BULUH CINA KABUPATEN KAMPAR PROVINSI RIAU. JOM Faperta 2017, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Putri, M.Z.; Yoza, D.; Arlita, T. KEANEKARAGAMAN JENIS POHON DI HUTAN ADAT RIMBO TUJUH DANAU DESA BULUH CINA KABUPATEN KAMPAR PROVINSI RIAU. JOM Faperta 2017, 4, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Mukhamadun; Efrizal, T.; Suardi, T. Valuasi Ekonomi Hutan Ulayat Buluhcina Desa Buluhcina Kecamatan Siak Hulu Kabupaten Kampar. J. Ilmu Lingkung. 3, 55–73.

- Yulia, S.S.; Thamrin, T. ANALISIS AKTIFITAS SOSIAL EKONOMI TERHADAP KUALITAS PERAIRAN DANAU OXBOW DI DESA BULUH CINA KECAMATAN SIAK HULU KABUPATEN KAMPAR PROVINSI RIAU. J. Ilmu Lingkung. 2013, 7, 187–200. [Google Scholar]

- Larasanti, D. Restorasi Gambut Berbasis Pemberdayaan Masyarakat Melalui Pembinaan Kelompok Masyarakat. In Proceedings of the Tantangan & Peluang Menuju Ekosistem Gambut Berkelanjutan; Universitas Riau, Universitas Andalas, PT. Kilang Pertamina Internasional RU II Sungai Pakning: Pekanbaru, October 2022; pp. 258–261.

- Syafrizal; Resdati Restorasi Gambut Berbasis Pemberdayaan Masyarakat (Community Empowerment Based Peat Restoration).; LPPM Universitas Muhammadiyah Purwokerto: Purwokerta, January 2020; pp. 596–601.

- Nusantara Atlas Maps Area of Interest. Available online: https://map.nusantara-atlas.org/?aoi=f48468f5-264a-4c00-815b-875fcae3c736.

- Champa, E. G. Kebun Sawit PT Agro Abadi Tidak Memiliki HGU, Ini Kata Kadis LHK Provinsi Riau. Available online: https://riaunews.com/utama/27986/ (accessed on 12 September 2023).

- Assis, J.C.; Hohlenwerger, C.; Metzger, J.P.; Rhodes, J.R.; Duarte, G.T.; Silva, R.A. da; Boesing, A.L.; Prist, P.R.; Ribeiro, M.C. Linking Landscape Structure and Ecosystem Service Flow. Ecosyst. Serv. 2023, 62, 101535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M.G.E.; Suarez-Castro, A.F.; Martinez-Harms, M.; Maron, M.; McAlpine, C.; Gaston, K.J.; Johansen, K.; Rhodes, J.R. Reframing Landscape Fragmentation’s Effects on Ecosystem Services. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2015, 30, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, P.; Hu, S.; Frazier, A.E.; Yang, S.; Song, X.; Qu, S. The Dynamic Relationships between Landscape Structure and Ecosystem Services: An Empirical Analysis from the Wuhan Metropolitan Area, China. J. Environ. Manage. 2023, 325, 116575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dede, M.; Sunardi, S.; Lam, K.C.; Withaningsih, S. Relationship between Landscape and River Ecosystem Services. Glob. J. Environ. Sci. Manag. 9, 637–652. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Chen, X.; Chen, W.; Ye, X. Identifying the Impact of Landscape Pattern on Ecosystem Services in the Middle Reaches of the Yangtze River Urban Agglomerations, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 5063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bürgi, M.; Silbernagel, J.; Wu, J.; Kienast, F. Linking Ecosystem Services with Landscape History. Landsc. Ecol. 2015, 30, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setten, G.; Stenseke, M.; Moen, J. Ecosystem Services and Landscape Management: Three Challenges and One Plea. Int. J. Biodivers. Sci. Ecosyst. Serv. Manag. 2012, 8, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Jiang, C.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Dong, B.; Yang, J.; Huang, W. Landscape Patterns and Their Spatial Associations with Ecosystem Service Balance: Insights from a Rapidly Urbanizing Coastal Region of Southeastern China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 1002902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamane, T. Statistics: An Introductory Analysis, 3rd ed.; Harper and Row: New York, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, R.C.; Carson, R.T. Using Surveys to Value Public Goods: The Contingent Valuation Method, 1st ed.; Resources for the Future: Washington D. C., 1989; Vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Energy, E.I.A. Method for Calculating Carbon Sequestration by Trees in Urban and Suburban Settings; Washington, D.C., 1998; pp. 1–16.

- Riau Provincial Government Penetapan Tarif Batas Atas Dan Tarif Batas Bawah BUMD Air Minum Se Provinsi Riau Tahun 2022; Decree of the Governor; 2022.

- BSN Penyusunan Neraca Sumber Daya-Bagian 1: Sumber Daya Air Spasial (SNI 19-6728.1-2002) 2002.

- Mudjiatko Kajian Harga Air Irigasi Untuk Peningkatan Pendapatan Petani (Kajian Kasus Di Petapahan, Kabupaten Kampar, Riau).; Fakultas Teknik Universitas Riau: Pekanbaru, May 2010; pp. 1–11.

- Seewiseng, L.; Bhaktikul, K.; Aroonlertaree, C.; Suaedee, W. The Water Footprint of Oil Palm Crop in Phetchaburi Province. Int. J. Renew. Energy 2012, 7, 49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Surendran, U.; Sushanth, C.M.; Joseph, E.J.; Al-Ansari, N.; Yaseen, Z.M. FAO CROPWAT Model-Based Irrigation Requirements for Coconut to Improve Crop and Water Productivity in Kerala, India. Sustain. Switz. 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangmeechai, A. Effects of Rubber Plantation Policy on Water Resources and Landuse Change in the Northeastern Region of Thailand. Geogr. Environ. Sustain. 2020, 13, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitriansyah; Widuri, E.S.; Ulmi, E.I. Analisa Kebutuhan Air Irigasi Untuk Tanaman Padi Dan Palawija Pada Daerah Irigasi Rawa (DIR) Danda Besar, Kabupaten Barito Kuala. Media Ilm. Tek. Sipil 2020, 8, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewi, S.; Khasanah, N.; Rahayu, S.; Ekadinata, A.; van Noordwijk, M. Carbon Footprint of Indonesian Palm Oil Production: A Pilot Study; Bogor, 2009; pp. 1–8.

- Lestari, N.S.; Noor’An, R.F. Carbon Sequestration Potential of Rubber Plantation in East Kalimantan.; Institute of Physics, 2022; Vol. 1109.

- Verwer, C.C.; van der Meer, P.J. Carbon Pools in Tropical Peat Forest: Towards a Reference Value for Forest Biomass Carbon in Relatively Undisturbed Peat Swamp Forest in Southeast Asia; Wageningen, 2010; pp. 1–67.

- International Monetary Fund Indonesia’s Transition toward a Greener Economy - Carbon Pricing and Green Financing; Washington, D.C., 2022; pp. 52–61.

- IBM Corp IBM SPSS Statistics for macOS 2021.

- Central Bureau of Statistics Indonesia [Seri 2010] Produk Domestik Regional Bruto Per Kapita (Ribu Rupiah), 2020-2022. Prod. Domest. Reg. Bruto Lapangan Usaha 2023.

- International Monetary Fund Indonesia: Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per Capita in Current Prices from 1987 to 2028 (in U.S. Dollars). Statista 2023.

- The World Bank; BPS Pilot Ecosystem Account for Indonesian Peatlands Sumatera and Kalimantan Islands; World Bank: Washington DC., 2019.

- Uda, S.K.; Hein, L.; Sumarga, E. Towards Sustainable Management of Indonesian Tropical Peatlands. Wetl. Ecol. Manag. 2017, 25, 683–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firzal, Y.; Faisal, G. Architecture and Socio-Cultural Life: Redefining Malay Settlement on the East Coast of Sumatera.; 2016; pp. 1–8.

- Taufik, M.; Haikal, M.; Widyastuti, M.T.; Arif, C.; Santikayasa, I.P. The Impact of Rewetting Peatland on Fire Hazard in Riau, Indonesia. Sustain. Switz. 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasetyawan, W. Willingness to Pay for Environmental Conservation of Peat and Aquatic Ecosystems in a Cash-Poor Community: A Riau Case Study. In Local Governance of Peatland Restoration in Riau, Indonesia; Okamoto, M., Osawa, T., Prasetyawan, W., Binawan, A., Eds.; Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd: Gateway East, Singapore, 2023; Vol. 1, pp. 193–209. [Google Scholar]

- Suwarno, A.; Hein, L.; Sumarga, E. Who Benefits from Ecosystem Services? A Case Study for Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. Environ. Manage. 2016, 57, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulya, N.A.; Nurlia, A.; Kunarso, A.; Martin, E.; Waluyo, E.A. Valuation of Goods and Services Derived from Plantation Forest in Peat Swamp Forest Area: The Case of South Sumatra Province.; Institute of Physics Publishing, September 2019; Vol. 308. [CrossRef]

- Sumarga, E.; Hein, L. Mapping Ecosystem Services for Land Use Planning, the Case of Central Kalimantan. Environ. Manage. 2014, 54, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossita, A.; Nurrochmat, D.R.; Boer, R.; Hein, L.; Riqqi, A. Assessing The Monetary Value Of Ecosystem Services Provided By Gaung – Batang Tuaka Peat Hydrological Unit (Khg), Riau Province. Heliyon 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Januar, R.; Sari, E.N.N.; Putra, S. Economic Case for Sustainable Peatland Management: A Case Study in Kahayan-Sebangau Peat Hydrological Unit, Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. Land Use Policy 2023, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarigan, S.; Zamani, N.P.; Buchori, D.; Kinseng, R.; Suharnoto, Y.; Siregar, I.Z. Peatlands Are More Beneficial If Conserved and Restored than Drained for Monoculture Crops. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aulia, A.F. Rural Livelihoods and Ecosystem Services in Oil Palm Landscapes in Riau, Sumatra, Indonesia. 2017, 1–197.

- Simangunsong, B.C.H.; Manurung, E.G.T.; Elias, E.; Hutagaol, M.P.; Tarigan, J.; Prabawa, S.B. Tangible Economic Value of Non-Timber Forest Products from Peat Swamp Forest in Kampar, Indonesia. Biodiversitas 2020, 21, 5954–5960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochmayanto, Y.; Darusman, D.; Rusolono, T. The Change of Carbon Stock and It’s Economic Value on Peat Swamp Forest Conversion towards Pulpwood Industrial Plantation Forest. J. Penelit. Hutan Tanam. 2010, 7, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerton, L. Economic Valuation of Wetlands: Total Economic Value. In The Wetland Book: I: Structure and Function, Management, and Methods; Springer Netherlands, 2018; pp. 2127–2132. ISBN 978-90-481-9659-3. [Google Scholar]

- Masiero, M.; Pettenella, D.; Boscolo, M.; Barua, S.K.; Animon, I.; Matta, R. Valuing Forest Ecosystem Services: A Training Manual for Planners and Project Developers. 2019.

- International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Peatlands and Climate Change. Available online: https://www.iucn.org/resources/issues-brief/peatlands-and-climate-change#:~:text=Worldwide%2C%20the%20remaining%20area%20of,types%20including%20the%20world's%20forests (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- Ulya, N.A.; Warsito, S.P.; Andayani, W.; Gunawan, T. Economic Value of Water for Domestic and Transportation-Case Study in Villages Around Merang Kepayang Peat Swamp Forest, South Sumatera Province. J. Mns. Dan Lingkung. 2014, 21, 232–238. [Google Scholar]

- Putra, E.I.; Saharjo, B.H.; Wasis, B.; Hero, Y.; Puspaningsih, N. Economic Loss Value from Land and Forest Fires in Oil Palm Plantation in Jambi, Indonesia.; Institute of Physics Publishing, June 2020; Vol. 504. [CrossRef]

- Saharjo, B.H.; Wasis, B. Valuasi Ekonomi Kerusakan Lingkungan Akibat Kebakaran Gambut Di Desa Mak Teduh Provinsi Riau. J. Trop. Silvic. 2019, 10, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.K.; Baral, H.; Laumonier, Y.; Okarda, B.; Purnomo, H.; Pacheco, P. Ecosystem Services under Future Oil Palm Expansion Scenarios in West Kalimantan, Indonesia. Ecosyst. Serv. 2019, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parlinah, N.; Djaenudin, D.; Iqbal, M.; Indartik; Suryandari, E.Y.; Salaka, F.J.; Kurniawan, A.S.; Effendi, R. Valuation of Rubber Farming Business in Support of Food Security: A Case Study in Pulang Pisau Regency.; IOP Publishing Ltd, November 2021; Vol. 917. [CrossRef]

- Bahuguna, V.K. Forests in the Economy of the Rural Poor: An Estimation of the Dependency Level. AMBIO J. Hum. Environ. 2000, 29, 126–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahapatra, A.K.; Albers, H.J.; Robinson, E.J.Z. The Impact of NTFP Sales on Rural Households’ Cash Income in India’s Dry Deciduous Forest. Environ. Manage. 2005, 35, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tieguhong, J.C.; Nkamgnia, E.M. Household Dependence on Forests around Lobeke Nationa l Park, Cameroon. Int. For. Rev. 2012, 14, 196–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponta, N.; Cornioley, T.; Waeber, P.O.; Dray, A.; Van Vliet, N.; Quiceno Mesa, M.P.; Garcia, C.A. Drivers of Transgression: What Pushes People to Enter Protected Areas. Biol. Conserv. 2021, 257, 109121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maryudi, A.; Devkota, R.R.; Schusser, C.; Yufanyi, C.; Salla, M.; Aurenhammer, H.; Rotchanaphatharawit, R.; Krott, M. Back to Basics: Considerations in Evaluating the Outcomes of Community Forestry. For. Policy Econ. 2012, 14, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robins, L.; van Kerkhoff, L.; Rochmayanto, Y.; Sakuntaladewi, N.; Agrawal, S. Knowledge Systems Approaches for Enhancing Project Impacts in Complex Settings: Community Fire Management and Peatland Restoration in Indonesia. Reg. Environ. Change 2022, 22, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strack, M.; Davidson, S.J.; Hirano, T.; Dunn, C. The Potential of Peatlands as Nature-Based Climate Solutions. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 2022, 8, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertiwi, N.; Tsusaka, T.W.; Nguyen, T.P.L.; Abe, I.; Sasaki, N. Nature-Based Carbon Pricing of Full Ecosystem Services for Peatland Conservation—A Case Study in Riau Province, Indonesia. Nat.-Based Solut. 2022, 2, 100023–100023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osawa, T. Rethinking the Local Wisdom Approach in Peatland Restoration through the Case of Rantau Baru: A Critical Inquiry to the Present-Day Concept of Kearifan Lokal. In Local Governance of Peatland Restoration in Riau, Indonesia: A Transdisciplinary Analysis; Okamoto, M., Osawa, T., Prasetyawan, W., Binawan, A., Eds.; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2023; pp. 119–145. ISBN 978-981-9909-02-5. [Google Scholar]

| No. | Variable | Description | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Landscape conditions | ||

| 1 | Protected area | Whether the household is located in the protected area |

|

| 2 | Peatland restoration projects | Whether the household is located in a peatland restoration site |

|

| 3 | Fire damaged-zones | Whether the household is located in a fire damaged-zone |

|

| 4 | Peat domes | Whether the household is located in an area with peat domes |

|

| 5 | Large scale oil palm plantations | Whether the household is located in an area with large scale oil palm plantations |

|

| 6 | Peat drainages | Whether the household is located in an area with peat drainages |

|

| B | The distance | ||

| 1 | Center of village | The distance from the household to the center of the village (km) |

|

| 2 | Local market | The distance from the household to the local market (km) |

|

| 3 | Peatland forests | The distance from the household to the peatland forests (km) |

|

| 4 | Protected area | The distance from the household to the protected area (km) |

|

| 5 | River | The distance from the household to the closest river (km) |

|

| No. | Ecosystem services | Calculation formulas | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Use value | ||

| i. Direct use value | |||

| Fishery | Pi is the market price of product (USD/kg), Qi is the quantity of product (kg/year), and j is the household | ||

| Wild plants and their outputs as a food source | |||

| Wild animals and their outputs as a food source | |||

| Ornamental animals and plants | |||

| Fibers and other materials | |||

| Medicines and other materials from wild animals and wild plants | |||

| Water for households |

|

Fmi is the number of family member, Wti is the water needed per people (m3/year) | |

| Water for agriculture |

|

Ari is the area of land for production (ha), Wti is the water needed per year (m3/ha), and Pli is the plant's intensity day per year | |

| Soil fertility | Pi is the market price of product (USD/kg), Qi is the quantity of product (kg/year), and j is the household | ||

| ii. Indirect use value | |||

| Fire prevention | Eci is the estimated cost of fire prevention (USD/incident), and Fri is the fire frequency. | ||

| Carbon sequestration | Pri is the carbon prices, Cri is the number of carbon stocks, Ari is the total area of peatlands, and Fci is the conversion factor. | ||

| iii. Option value | |||

| Habitats for endemic/endangered species | WTP is the maximum willingness to pay expressed by individual households, and n is the number of observations. | ||

| B | Non-use value | ||

| i. Bequest value | |||

| Biodiversity for future generation | WTP is the maximum willingness to pay expressed by individual households, and n is the number of observations. | ||

| ii. Existence value | |||

| Spiritual, sacred and religious values | Ari is the total area of the sacred forest, Pri is the price of land (oil palm plantation, USD/ha), and n is the number of total households as a population. |

| Ecosystem services | Price | Quantity | Assumption | Data sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water for household | 0.80 USD/m3 | 21.90 m3/people/year | Average annual water use per person | [59] [60] |

| Water for agriculture | 0.0019 USD/m3 | Oil palm 21,296 m3/ha/year Coconut 17,520 m3/ha/year Rubber 14,221 m3/ha/year Rice 391,495 m3/ha/year |

Annual water use for specific crops per hectare | [61] [62] [63] [64] [65] |

| Carbon sequestration | 2 USD/tCO2 | Oil palm 40 tC/ha Rubber 75.71 tC/ha Coconut 100 tC/ha |

Carbon sequestration rate per hectare for specific crops | [66,67,68] [69] |

| Sacred forest | 8,643.61 USD/ha/year | 963.33 ha | Value of the forest if it were converted into an oil palm plantation | Questionnaire data |

| No. | Peatland ecosystem services | Value (USD/hh/year) | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Use value | 2,566.44 | 80.85 | |

| i | Direct use value | 1,983.83 | 77.30 |

| 1. Fishery | 807.56 | 40.71 | |

| 2. Wild plants and their outputs as a food source | 104.48 | 5.27 | |

| 3. Wild animals and their outputs as a food source | 153.67 | 7.75 | |

| 4. Ornamental animals and plants | 36.28 | 1.83 | |

| 5. Fibres and other materials | 22.86 | 1.15 | |

| 6. Medicines and other materials from wild animals and wild plants | 28.44 | 1.43 | |

| 7. Water for households | 57.82 | 2.91 | |

| 8. Water for agriculture | 63.77 | 3.21 | |

| 9. Soil fertility | 708.96 | 35.74 | |

| ii | Indirect use value | 579.33 | 29.20 |

| 1. Fire prevention | 69.85 | 12.06 | |

| 2. Carbon sequestration | 509.49 | 87.94 | |

| iii | Option value | ||

| 1. Habitats for endemic/endangered species | 3.28 | 0.13 | |

| Non-use value | 607.88 | 19.15 | |

| i | Bequest value | ||

| 1. Biodiversity for future generation | 3.4 | 0.56 | |

| ii | Existence value | ||

| 1. Spiritual, sacred and religious values | 604.48 | 99.44 | |

| Total economic value | 3,174.32 | 100 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).