Submitted:

28 December 2023

Posted:

29 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Capacity Building

1.2. What is the Problem?

1.3. Conceptualising Capacity Building for Africa’s Transport

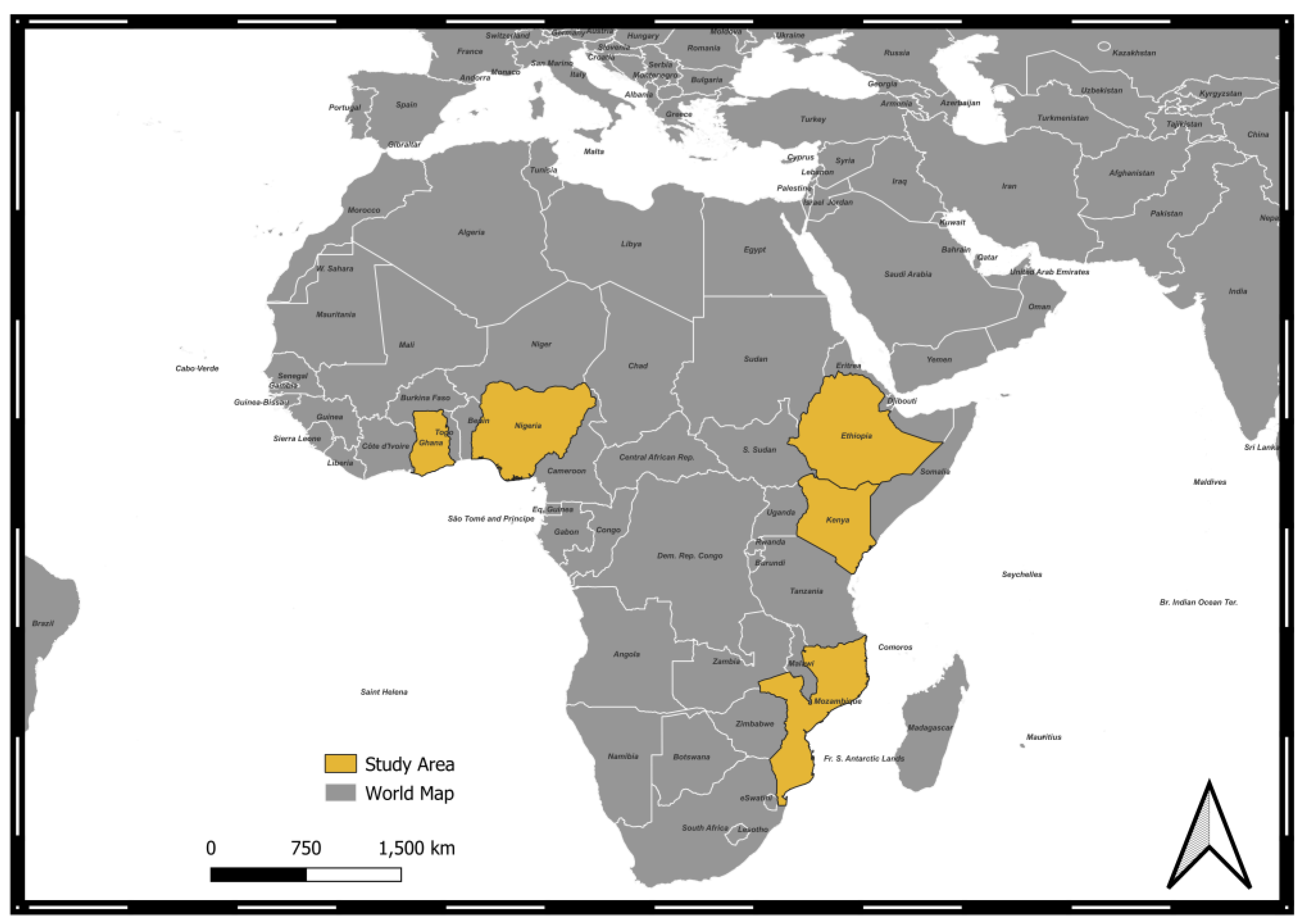

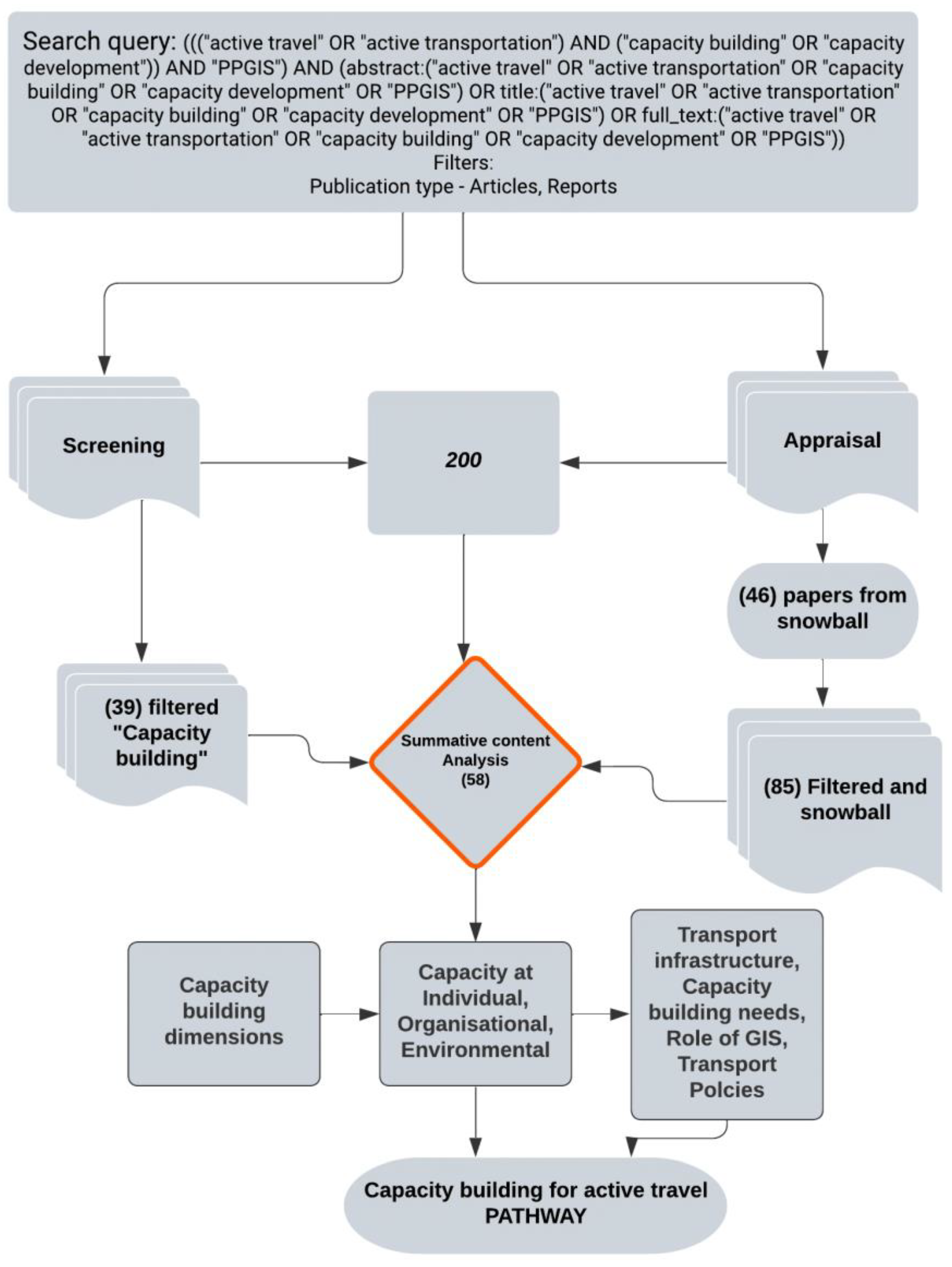

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Review

2.2. Literature Review Approach

2.3. Literarure Screening and Appraisal

3. Results

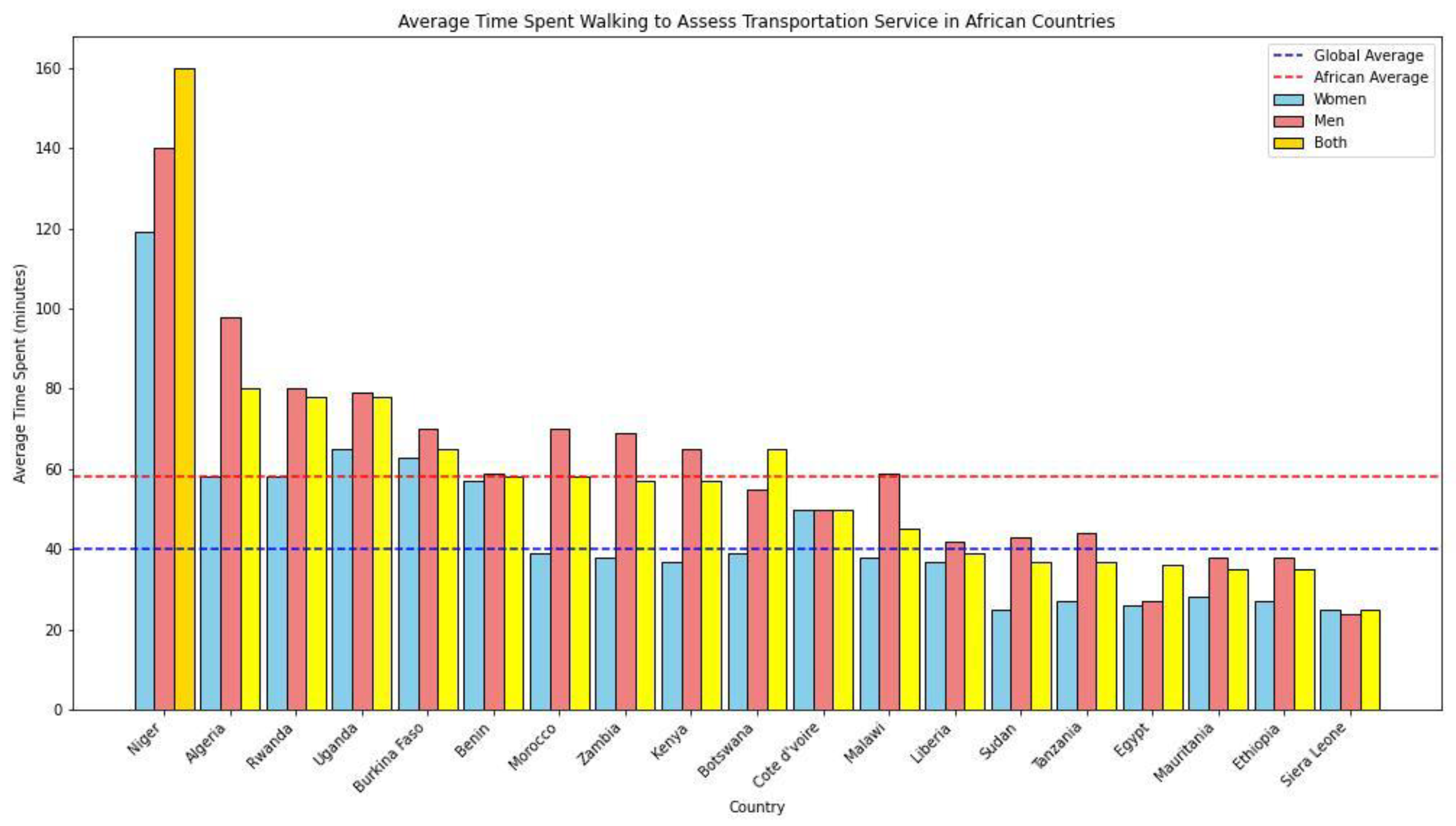

3.1. Transport Culture

3.2 Infrastructure

3.2 Transport Capacity Building Needs

3.3 Transport Policy and Implementation

3.4 The Role of GIS in Capacity Building

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bachand-Marleau, Julie; Larsen, J.; El-geneidy, A. (2011). Much-Anticipated Marriage of Cycling and Transit." Transportation Research Record. [CrossRef]

- Wiertlewski, S. (2019). “Iść, Czyli Jechać. Językowy Obraz Świata w Cyklolekcie.” Investigationes Linguisticae. [CrossRef]

- Habitat, U.N. The State of African Cities; The United Nations Settlements Programme: Nairobi, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Habitat, U.N. Cities and Climate Change; UN Habitat: Nairobi, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Loukaitou-Sideris, A. Transportation, Land Use, and Physical Activity: Safety and Security Considerations 2004.

- Odero, W.; Khayesi, M.; Heda, P.M. Road Traffic Injuries in Kenya: Magnitude, Causes and Status of Intervention. Injury control and safety promotion 2003, 10, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howe, J. Enhancing Nonmotorized Transportation Use in Africa-Changing the Policy. Transportation research record 1995, 22–26. [Google Scholar]

- Candiracci, Sara. (2010) How Can Better Mobility Make African Cities More Inclusive. Public Transport International.

- Mitullah, W.V.; Vanderschuren, M.; Khayesi, M. (Eds.). Non-Motorized Transport Integration into Urban Transport Planning in Africa. Taylor & Francis. 2017.

- Sietchiping, R.; Permezel, M.J.; Ngomsi, C. Transport and Mobility in Sub-Saharan African Cities: An Overview of Practices, Lessons and Options for Improvements. Cities 2012, 29, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacou, K.P.; Ika, L.A.; Munro, L.T. Fifty Years of Capacity Building: Taking Stock and Moving Research Forward 1. Public Administration and Development 2022, 42, 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkerhoff, D.W.; Morgan, P.J. Capacity and Capacity Development: Coping with Complexity. Public Administration and Development: The International Journal of Management Research and Practice 2010, 30, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venner, M. The Concept of ‘Capacity’in Development Assistance: New Paradigm or More of the Same? Global Change, Peace & Security 2015, 27, 85–96. [Google Scholar]

- Grauwe, A. Without Capacity, There Is No Development; UNESCO, International Institute for Educational Planning: Paris, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Barakat, S.; Chard, M. Theories, Rhetoric and Practice: Recovering the Capacities of War-Torn Societies. Third world quarterly 2002, 23, 817–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, S.A.; Engel, N. Effective Institution Building. A Guide for Project Designers and Project Managers, Based on Lessons Learned from the AID Portfolio 1982.

- Godfrey, M.; Sophal, C.; Kato, T.; Piseth, L.V.; Dorina, P.; Saravy, T.; Sovannarith, S. Technical Assistance and Capacity Development in an Aid-Dependent Economy: The Experience of Cambodia. World Development 2002, 30, 355–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lempert, D. A Quick Indicator of Effectiveness of" Capacity Building" Initiatives of NGOs and International Organizations. European Journal of Government and Economics 2015, 4, 155–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, C. Between Pragmatism and Idealism: Implementing a Systemic Approach to Capacity Development. IDS Bulletin 2010, 41, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harfst, J.; Marot, N. Capacity-Building in Old Industrialised Regions: A Success Factor in Regional Development. Capacity Building and Development: Perspectives, Opportunities and Challenges 2013, 117–134.

- Yeatman, H.R.; Nove, T. Reorienting Health Services with Capacity Building: A Case Study of the Core Skills in Health Promotion Project. Health Promotion International 2002, 17, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, Y.; Garvin, M.J.; Hall, R.P. Pathways to Better Project Delivery: The Link between Capacity Factors and Urban Infrastructure Projects in India. World Development 2017, 94, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühl, S. Capacity Development as the Model for Development Aid Organizations. Development and Change 2009, 40, 551–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, J. Improving International Capacity Development. Bright Spots; Palgrave Macmillan, 2013;

- Straussman, J.D. An Essay on the Meaning (s) of “Capacity Building”—With an Application to Serbia. International Journal of Public Administration 2007, 30, 1103–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance; Cambrige University Press, 1990.

- Williams, M.J. Beyond State Capacity: Bureaucratic Performance, Policy Implementation and Reform. Journal of Institutional Economics 2021, 17, 339–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkerhoff, D.W. The State and International Development Management: Shifting Tides, Changing Boundaries, and Future Directions. Public Administration Review 2008, 68, 985–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honadle, B.W. A Capacity-Building Framework: A Search for Concept and Purpose; Public Sector Performance, 2018.

- Matachi, A. Capacity Building Framework. United Nations Economic Commission for Africa; Online Submission, 2006;

- King, C.; Cruickshank, M. Building Capacity to Engage: Community Engagement or Government Engagement? Community Development Journal 2012, 47, 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, K.L. Maritime Security and Capacity Building in the Gulf of Guinea: On Comprehensiveness, Gaps, and Security Priorities. African Security Review 2017, 26, 237–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forget, Y.; Shimoni, M.; Gilbert, M.; Linard, C. Mapping 20 Years of Urban Expansion in 45 Urban Areas of Sub-Saharan Africa. Remote Sensing 2021, 13, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasmito, S.D.; Taillardat, P.; Clendenning, J.N.; Cameron, C.; Friess, D.A.; Murdiyarso, D.; Hutley, L.B. Effect of Land-use and Land-cover Change on Mangrove Blue Carbon: A Systematic Review. Global Change Biology 2019, 25, 4291–4302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.F.; Shannon, S.E. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qualitative Health Research 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fereday, J. , & Muir-Cochrane, E. Demonstrating Rigor Using Thematic Analysis: A Hybrid Approach of Inductive and Deductive Coding and Theme Development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 2006, 5, 80–92. [Google Scholar]

- Kaul, R.N. Dynamics of Tourism: A Trilogy. Transportation and Marketing; Sterling Publishers, 1985;

- In Tourism Planning; Gunn, C., Ed.; Taylor and Francis: New York, 1988.

- Inskeep, E. Tourism Planning: An Integrated and Sustainable Development Approach; John Wiley & Sons, 1991;

- Bofinger, H. Africa’s Transport Infrastructure: Mainstreaming Maintenance and Management; World Bank Publications, 2011;

- Adeyemo, B.A. Colonial Transport System in Africa: Motives, Challenges and Impact. African Journal of History and Archaeology 2019, 4, 14–26. [Google Scholar]

- Chakwizira, J. , Bikam, P., & Adeboyejo, T.A. (). Different Strokes for Different Folks: Access and Transport Constraints for Public Transport Commuters in Gauteng Province, South Africa. Int. J. Traffic. Transp. Eng. 2018, 8, 58–81. [Google Scholar]

- Middleton, J. The Socialites of Everyday Urban Walking and the ‘Right to the City. ’ Urban studies 2018, 55, 296–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, J. The Walkable City: Dimensions of Walking and Overlapping Walks of Life; Taylor & Francis, 2021;

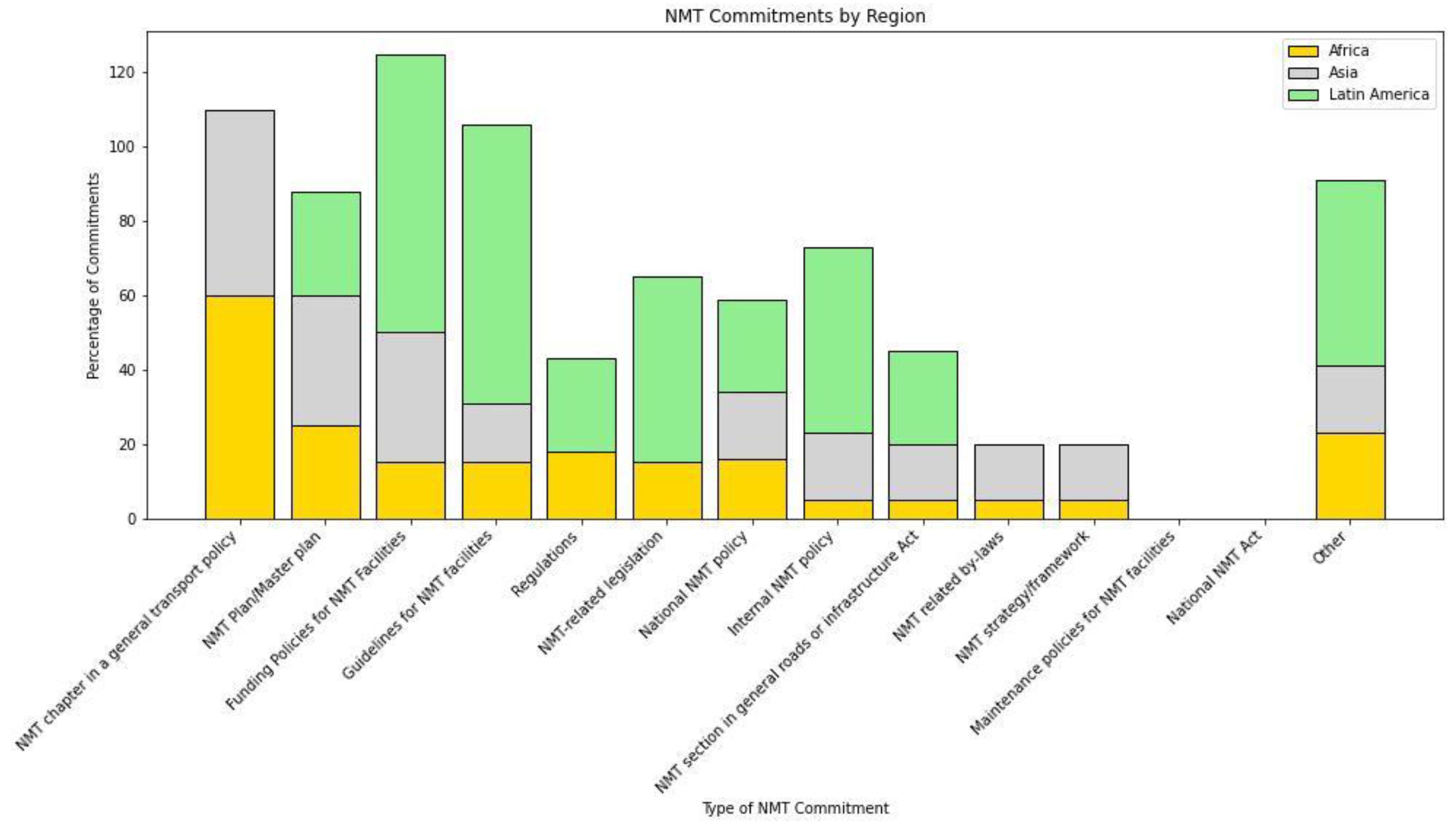

- UNEP, 2022. Walking and Cycling in Africa: Evidence and Good Practice to Inspire Action.

- Ouongo, C. (2010). Problematique Du Transport et de La Securite Routiere a Ouagadougou.

- Ndebele, R.; Aigbavboa, C.; Ogra, A. Urban Transport Infrastructure Development in African Cities: Challenges and Opportunities. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, Johannesburg, South Africa; p. 2018833.

- Gwilliam, K. Urban Transport in Developing Countries. Transport Reviews 2003, 23, 197–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teravaninthorn, S.; Raballand, G. Transport Prices and Costs in Africa: A Review of the Main International Corridors 2009.

- Rajé, F.; Tight, M.; Pope, F.D. Traffic Pollution: A Search for Solutions for a City like Nairobi. Cities 2018, 82, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikitas, A.; Tsigdinos, S.; Karolemeas, C.; Kourmpa, E.; Bakogiannis, E. Cycling in the Era of COVID-19: Lessons Learnt and Best Practice Policy Recommendations for a More Bike-Centric Future. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, S.; Behrens, R.; Zuidgeest, M. The Relationship between Transit-Oriented Development, Accessibility and Public Transport Viability in South African Cities: A Literature Review and Problem Framing 2018.

- Falchetta, G.; Hammad, A.T.; Shayegh, S. Planning Universal Accessibility to Public Health Care in Sub-Saharan Africa. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2020, 117, 31760–31769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linard, C.; Gilbert, M.; Snow, R.W.; Noor, A.M.; Tatem, A.J. Population Distribution, Settlement Patterns and Accessibility across Africa in 2010. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, 31743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, B.; Roberts, P. Walk Urban: Demand, Constraints, and Measurement of the Urban Pedestrian Environment 2008.

- Loo, B.P.; Siiba, A. Active Transport in Africa and beyond: Towards a Strategic Framework. Transport Reviews 2019, 39, 181–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

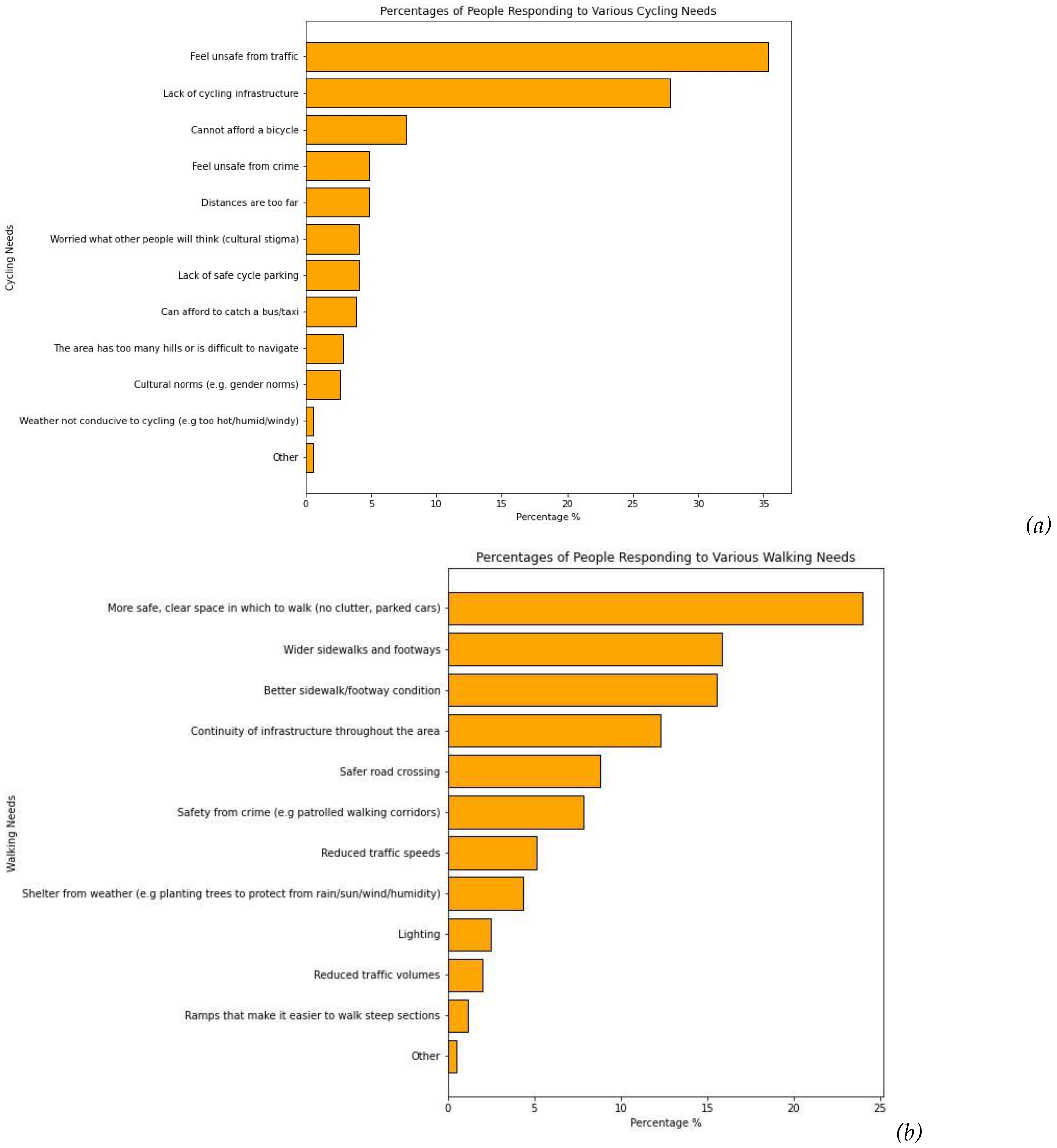

- Basil, P.; Nyachieo, G. EXPLORING PERCEPTIONS AND BARRIERS TO WALKING AND CYCLING IN URBAN AREAS IN KENYA: A CASE OF NAIROBI METROPOLITAN AREA. Frontiers in Sustainable Cities 2023, 183. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, G. Transport Services and Their Impact on Poverty and Growth in Rural Sub-Saharan Africa 2013.

- Mbara, T.C. (2002) Activity Patterns, Transport and Policies for the Urban Poor in Harare, Zimbabwe. Final Country Report.[En Ligne].

- Silva, C.F.A.; Andrade, M.O.; Maia, M.L.A.; Santos, A.M.; Portis, G.T. Remote Sensing for Identification of Trip Generating Territories in Support of Urban Mobility Planning and Monitoring. GeoJournal 2023, 88, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.; Olsen, M.J.; Roe, G.V.; Glennie, C. Synthesis of Transportation Applications of Mobile LiDAR. Remote Sensing 2013, 5, 4652–4692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loli, M.; Kefalas, G.; Dafis, S.; Mitoulis, S.A.; Schmidt, F. Bridge-Specific Flood Risk Assessment of Transport Networks Using GIS and Remotely Sensed Data. Science of the Total Environment 2022, 850, 157976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somantri, L. The Role of GIS and Remote Sensing for Population Mobility Mapping. In Proceedings of the Seventh Geoinformation Science Symposium 2021; SPIE, December 2021; Vol. 12082; pp. 416–425. [Google Scholar]

- Banister, D. The Sustainable Mobility Paradigm. Transport policy 2008, 15, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alattar, M.A.; Cottrill, C.; Beecroft, M. Public participation geographic information system (PPGIS) as a method for active travel data acquisition. Journal of Transport Geography 2021, 96, 103180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupton, D. Lively Data, Social Fitness and Biovalue: The Intersections of Health and Fitness Self-Tracking and Social Media. The Sage Handbook of Social Media; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Muller, M. Developing a GIS-Based Decision-Support Tool for Bicycle Lane Network Expansion in Johannesburg. Journal of Transport Geography 2016, 57, 152–160. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, J.; McArthur, D.P.; Livingston, M. The Evaluation of Large Cycling Infrastructure Investments in Glasgow Using Crowdsourced Cycle Data. Transportation 2020, 47, 2859–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griswold, J.B.; Medury, A.; Schneider, R.J. Pilot Models for Estimating Bicycle Intersection Volumes. Transportation research record 2011, 2247, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Mobasheri, A. Utilizing Crowdsourced Data for Studies of Cycling and Air Pollution Exposure: A Case Study Using Strava Data. International journal of environmental research and public health 2017, 14, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shearmur, R. Dazzled by Data: Big Data, the Census and Urban Geography. Urban Geography 2015, 36, 965–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olteanu-Raimond, A.M.; Laakso, M.; Antoniou, V.; Fonte, C.C.; Fonseca, A.; Grus, M.; Skopeliti, A. VGI in National Mapping Agencies: Experiences and Recommendations. In Mapping and the Citizen Sensor; Ubiquity Press, 2017; pp. 299–326.

- Mbiru, S.S. Capacity Development to Support Planning and Decision Making for Climate Change Response in Kenya. In Addressing the Challenges in Communicating Climate Change Across Various Audiences; 2019; pp. 213–230.

- Livingston, M. , McArthur, D., Hong, J., & English, K. () Predicting Cycling Volumes Using Crowdsourced Activity Data. Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science 2021, 48, 1228–1244. [Google Scholar]

- Chrysostome, E.; Munthali, T.; Ado, A. Capacity Building in Africa: Toward an Imperative Mindset Transformation. In Capacity Building in Developing and Emerging Countries: From Mindset Transformation to Promoting Entrepreneurship and Diaspora Involvement; 2019; pp. 7–41.

- Wunsch, J.S. Decentralization, Local Governance and ‘Recentralization’ in Africa. Public Admin & Development 2001, 21, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colarossi, L.G.; Dean, R.; Balakumar, K.; Stevens, A. Organizational Capacity Building for Sexual Health Promotion. American Journal of Sexuality Education 2017, 12, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurba, M.; Ross, H.; Izurieta, A.; Rist, P.; Bock, E.; Berkes, F. Building Co-Management as a Process: Problem Solving through Partnerships in Aboriginal Country, Australia. Environmental management 2012, 49, 1130–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glaser, M.; Blake, O.; Bertolini, L.; Brömmelstroet, M.; Rubin, O. Learning from Abroad: An Interdisciplinary Exploration of Knowledge Transfer in the Transport Domain. Research in Transportation Business & Management 2021, 39, 100531. [Google Scholar]

- Tsafack Nanfosso, R. The State of Capacity Building in Africa. World Journal of Science, Technology and Sustainable Development 2011, 8, 195–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manabe, Y.C. , Katabira, E., Brough, R.L., Coutinho, A.G., Sewankambo, N., & Merry, C. (). Developing Independent Investigators for Clinical Research Relevant for Africa. Health Research Policy and Systems 2011, 9, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Karani, P. Constraints for Activities Implemented Jointly (AIJ) Technology Transfer in Africa. Renewable Energy 2001, 22, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickerstaff, K.; Tolley, R.; Walker, G. Transport Planning and Participation: The Rhetoric and Realities of Public Involvement. Journal of Transport Geography 2002, 10, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domenico, M.; Tracey, P.; Haugh, H. Social Economy Involvement in Public Service Delivery: Community Engagement and Accountability. Regional Studies 2009, 43, 981–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, E.J.; Slyke, D.M.; Rogers, J.D. An Empirical Examination of Public Involvement in Public-Private Partnerships: Qualifying the Benefits of Public Involvement in PPPs. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 2016, 26, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallis, J.F.; Cerin, E.; Conway, T.L.; Adams, M.A.; Frank, L.D.; Pratt, M.; Owen, N. Physical Activity in Relation to Urban Environments in 14 Cities Worldwide: A Cross-Sectional Study. The Lancet 2016, 387, 2207–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araya-Quesada, M.; Degrassi, G.; Ripandelli, D.; Craig, W. Key Elements in a Strategic Approach to Capacity Building in the Biosafety of Genetically Modified Organisms. Environmental biosafety research 2010, 9, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalbarczyk, A.; Davis, W.; Kalibala, S.; Geibel, S.; Yansaneh, A.; Martin, N.A.; Manabe, Y.C. Research Capacity Strengthening in Sub-Saharan Africa: Recognizing the Importance of Local Partnerships in Designing and Disseminating HIV Implementation Science to Reach the 90–90–90 Goals. AIDS and Behavior 2019, 23, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohenhen, S. Performing Arts and Culture Industry and Human Capacity Building in Africa. Performing Arts 2017, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Nautiyal, S.; Klinsky, S. The Knowledge Politics of Capacity Building for Climate Change at the UNFCCC. Climate Policy 2022, 22, 576–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, T.C. , & le Roux, E. (). Capacity Building for Effective Municipal Environmental Management in South Africa. WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment 2006, 93. [Google Scholar]

- Gore, C. Cities and the Environment in Sub-Saharan Africa." The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Environmental Politics. 2021.

| Level of Capacity | How to meet the Requirements | Elements (INDICATORS) |

|---|---|---|

| Individual | - Improving perceptions of- cycling and walking as activities that are not limited to those with lower socioeconomic status. - Encouraging the advantages of cycling for health, including enhanced cardiovascular wellness and weight control. Providing education and skill-building opportunities for safe cycling practices. - Encouraging a shift in attitudes towards considering cycling/walking as an eco-friendly means of transportation. |

-Knowledge: Understanding of cycling safety rules and the benefits of cycling. -Skills: Ability in cycling securely under various traffic circumstances. -Value: The recognition of cycling as a sustainable and eco-friendly means of transportation. -Attitude: Positive mindset towards cycling as a viable means of transport. -Health: Improved physical fitness and wellbeing through regular cycling. -Awareness: Recognition of cycling’s/walking role in reducing carbon emissions. |

| Organization | -Strategies that will influence an organization's performance. | -Physical resources: facilities, equipment, materials, etc -Capital Intellectual resources: organizational strategy, strategic planning, production technology, program management, process management, inter-institutional linkage -Organizational governance structure and management methods which affect the utilization of the resources (human, physical intellectual assets) |

| Environment | The environment and conditions necessary for operating capacity at the individual and organizational levels. | Formal institutions (laws, policies, decrees, ordinances, membership rules, etc) Informal institutions (customs, cultures, norms, etc) Social capital, social infrastructure, etc. Capacities of individuals and organizations under the environment |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).