Submitted:

29 December 2023

Posted:

29 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

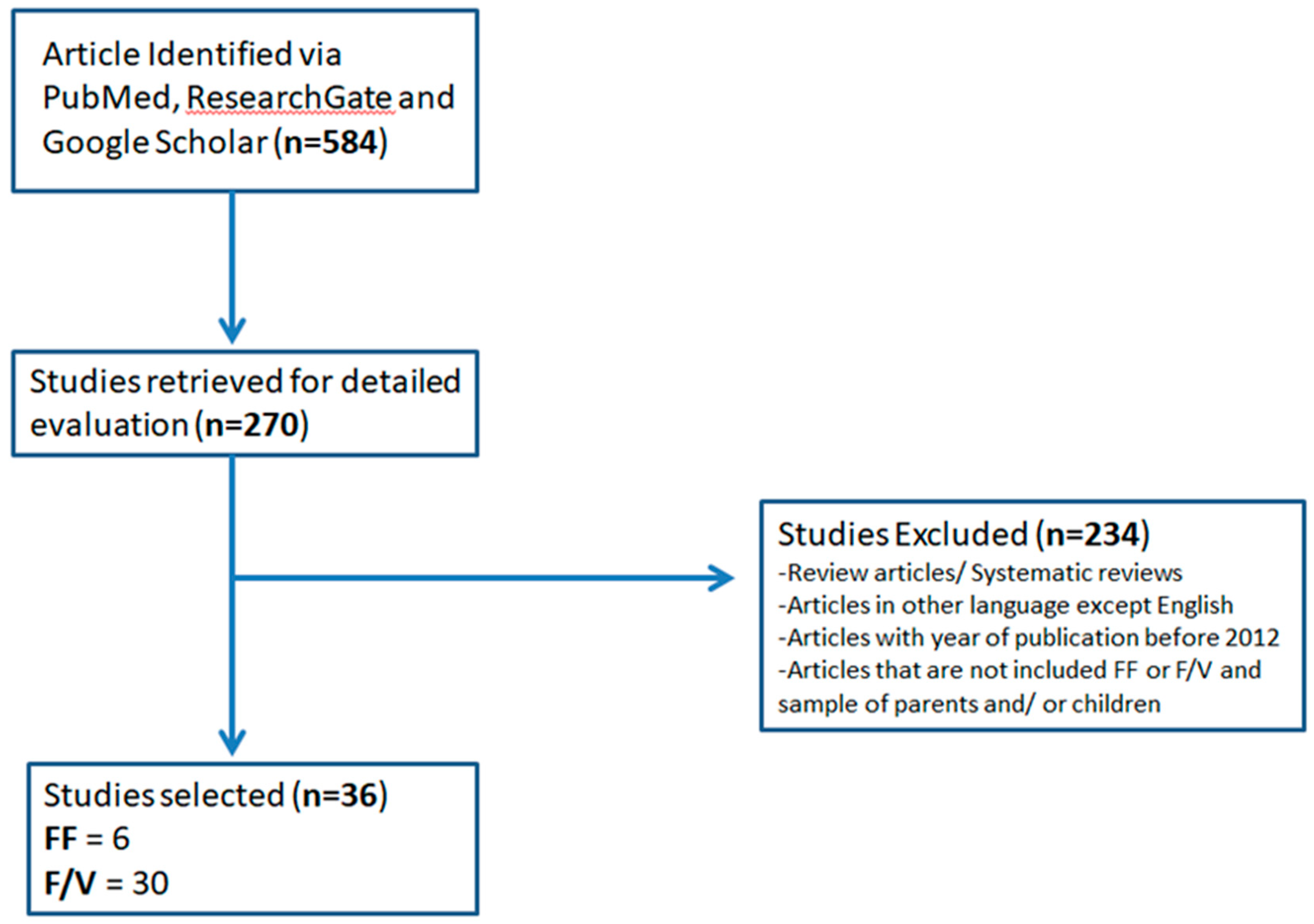

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Studies with Children/ Parents and FFs consumption

| Sources | Year | Country | Method | Sample size | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Krystallis | 2012 | Athens, Greece | Experimental study | parents of 5- to 14-year-old child | Τhe more parents were aware of functional foods, the more they preferred them. The type of food labeled as a functional food played a role in purchasing it when consumers were unaware of its functionality |

| Rahmawaty | 2013 | Wollongong, New South Wales, Australia | Cross-sectional study | 262 parents who have a child aged 9–13 years | Among families who consume fish, taste was the most important factor to choose it, as well as preferences of individual family members, but not for those who don’t eat fishes. Price was the major barrier to consumption of fresh fish, but not for canned fish and n–3-enriched foods, in either those who consume or not these foods. |

| Deleon | 2015 | Mississippi, U.S.A. | Descriptive study | parents | ‘Significant relationships in parental age, household income, education, marital status, BMI, gender, self-reported overall health and age of children in the household to including functional foods in their children’s diet’. Parental race/ethnicity had the most significant relationship. |

| Annunziata | 2015 | Campania, Italy | Web survey | 365 parents of children aged between 1 and 10 years | Although parents didn’t know enough about functional foods, they had a strong interest in the functional nutrition of their children. The frequency of buying functional foods targeting in children depends not only on parents’ socio-demographics but also on their nutritional knowledge, confidence and familiarity with FFs. |

| Weiss | 2016 | Mississippi, U.S.A. | Quantitative analytical cross-sectional study | 202 parents | The consumption of functional foods by parents has a greater effect on the consumption of functional foods by children than the awareness of functional foods. |

| Mohamad | 2018 | Malaysia | Qualitative Study | parents | Parents appeared confident in their capacity to incorporate functional weaning foods into their children’s diets. Parents recognize the health benefit of consuming functional weaning foods and that encouraged them to purchase them for their baby. |

3.2. Studies with Children/ Parents and Fruit/Vegetables consumption

| Sources | Year | Country | Method | Sample size | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lazzeri | 2013 | Italy | Cross-sectional study | 3291 students (11-, 13- and 15-year-old) | - A low frequency of F&V consumption was associated with irregular breakfast consumption. - Significant association between irregular snack intake and low frequency of fruit consumption, but not for vegetables intake. |

| Lynch | 2013 | 10 countries: Bulgaria, Finland, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Norway, Portugal, Slovenia, Sweden and the Netherlands |

Cross-sectional survey | 8158 children | - On average 53,3% of the children mentioned not to eat fruit daily and 44,9 % mentioned eating vegetables less than once daily. - Children do not reach the WHO recommendation for F&V intake, with only 23,5% of the whole sample meet the recommendations. |

| Attorp | 2014 | British Columbia, Canada | Cross-sectional study | 773 fifth-and sixth-grade school children and their parents | - Parent’s education and income were not significantly associated with child F&V intake. - Parental race/ethnicity had the most significant relationship. |

| de Jong | 2014 | Zwolle, the Netherlands | Cross-sectional study | 4072 children aged 4-13 years | -Children who don’t eat vegetables every day are associated with overweighting and a medium SES background. |

| Draxten | 2014 | Mineapolis, U.S.A. | Randomized controlled trial |

160 Parent-child dyads | - Parental role modeling of F&V intake was associated with children who consume every day four servings of F&V. - Children have similar perceptions with their parents’ role modeling behavior of fruit and green salads at dinner. |

| Lehto [53] | 2014 | Ten European countries: Bulgaria, Finland, Germany, Greece, Iceland, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Slovenia, Sweden |

Cross-sectional study | 8159 eleven-year-old children and their parents | -In five of the ten countries, children with higher educated parents were more likely to mention that they eat fruits every day. |

| Wolnicka | 2014 | Poland | Cross-sectional study | 1255 children (aged 9 years) and their parents. | -The children’s consumption of F&V was affected by the F&V consumption of their parents. -Parental education affected only the frequency of fruit intake. - Were correlated parents’ knowledge of the recommended consumption and the frequency of F&V intake by children. |

| Jackson | 2015 | Corvallis, U.S.A. | Cross-sectional study | 102 children and their parents | -Family – home Nutrition environment (FN) and children’s dietary had positive association between more frequent intakes of F&V at meals or snacks and greater F&V consumption among children. |

| Mantziki | 2015 | EPHE project: 7 European countries (Belgium, France, Greece, Portugal, Romania, The Netherlands, Bulgaria) | Follow up study | 1266 children and their families | - Children with mothers of high educational level consumed more F&V than their peers of low socio-economic status. - Parents seem to have knowledge of the perceived health benefit of functional weaning foods that encouraged them to purchase them for their baby. |

| Schoeppe | 2015 | Australia | Cross-sectional study | 173 parent–child dyads | -Maternal but not paternal support for F&V was positively associated with children’s F&V behavior. |

| Yannakoulia | 2016 | Greece | Observational study | 25309 children (3–12 years old) and adolescents (13–18 years old) | -The higher the Family Affluence Scale (FAS score), the greater the percentage of children and adolescents who consume F&V every day. |

| Hong | 2017 | Nakhon Pathom, Thailand |

Cross-sectional study | 609 students (grade 4-6) | -Higher maternal education level be significantly associated with total F&V intake. |

| Coto | 2019 | Florida, U.S.A. | Pilot study | 86 parent - child | - The majority of parents (54%) didn’t reach the recommendations for F&V and were classified as unhealthy role models. -Parents considered healthy role models were more likely to have a child with higher F&V intake. |

| Groele | 2019 | Poland | Observational study | 1200 Polish mothers of children aged 3–10 years | -Children of mothers who had a lower level of education more often than others consumed fruits alone as a dish. -Children of mothers who had a higher level of education had a higher consumption of vegetables than others. -Children of mothers with low income had a lower consumption of vegetables than others. |

| Quezada-Sánchez | 2019 | Mexico | Observational study | 1041 children | -A higher maternal educational level was associated with a higher probability of intake of foods with a high micronutrient density such as F&V. -Children of mothers with paid employment have a lower probability of consuming vegetables. |

| Benetou | 2020 | Greece | Cross-sectional study |

3525 adolescents | -More than 60% of the adolescents didn’t meet the reccomantation of of F&V daily consumption. |

| Eliason | 2020 | Phoenix, U.S.A. | Cross-sectional study |

2229 households | - Most children, especially in the younger age groups, reach the recommendation for daily amount of fruit. -The majority of children in all age/sex categories fell short of the recommendations for vegetables. |

| Etayo | 2020 | Six European centres (Belgium, Bulgaria, Germany, Greece, Poland and Spain) |

Cross-sectional study |

6633 preschool children | -Parental role has moderate influence with raise in fruit consumption to 19,3% of fruits consumption in European pre-schoolers and the 17,8% of vegetables consumption in boys and 21,9% of vegetable consumption in girls. |

| Malisova | 2021 | Greece | Cross-sectional study |

609 School Lunch recipients and 736 control subjects | -School Lunch recipients reported higher fruit consumption. |

| Papamichael | 2021 | 6 European countries: Bulgaria, Hungary, Belgium, Finland, Greece, Spain |

Cross-sectional study | parent-dyads (fathers, n = 10,038) and school children (n = 12,041) | -Τhere were positive associations between fathers’ F&V consumption and frequency of children’s consumption. -60% of fathers and less than 50% of children intaked F&V 1–2 times/ day, which does not reach the current WHO recommendations. |

| Pereira | 2021 | Portugal | Cross-sectional study |

678 children from the fifth and sixth grades | -The amount of F&V intake is below the “five pieces per day” recommendation. |

| Barrantes | 2022 | Six countries: Bulgaria, Hungary, Belgium, Finland, Greece, Spain |

Cross-sectional analysis | 6705 parent–child dyads | -Parental education was associated with children’s higher intake of F&V. |

| Boelens | 2022 | The Netherlands | Cross-sectional study | 5010 parents of 4- to 12-year-olds | -Low/ intermediate educated parents are associated with a higher risk of a low vegetable intake. -Low/intermediate parental education is associated with low F&V intake in children. |

| LeBlanc | 2022 | Canada | Cross-sectional study | 1054 students (467 boys and 570 girls) | -Adolescents who had better cooking and food skills mentioned having healthier eating habits and consuming more F&V. -Food and cooking skills were associated with healthier eating behaviors and greater F&V consumption among both boys and girls. |

| Linde | 2022 | Mineapolis, U.S.A. | Randomized controlled trial | 114 children (7-10 years old) and their parents | -Higher Healthy Eating Index- total scores were associated with children’s observations of their parent usually consuming fruit. |

| Charneca | 2023 | Portugal | Cohort study | 89 parents/ caregivers of one 2- to 6-year-old child | -Fruit consumption was higher than vegetable consumption. |

| Hamner | 2023 | U.S.A. | Cross-sectional study | 18386 children (1-5 years) | -In 20 states of U.S.A. more than one half of children didn’t eat a vegetable every day. -Nearly one third (32,1%) of children aged 1–5 years didn’t eat fruit daily and nearly one half (49,1%) didn’t eat vegetable every day. |

| Serasinghe | 2023 | Finland | Cross-sectional study | 574 children and their parents | -There is positive association between higher parental education level and children’s F&V intake. |

| Shrestha | 2023 | Pokhara, Nepal | Cross-sectional study | 352 children | -None of the children met the WHO recommendation of ≥ five servings of F&V daily. -Children whose parent’s education level was bachelor’s and above and have a family income of more than NRs 40,000 significantly consumed adequate F&V. |

| Siopis | 2023 | Six European countries: Belgium, Bulgaria, Finland, Greece, Hungary, Spain | Cross-Sectional Analysis | 9576 children–parents pairs | -When parents had higher education, families consumed more portions of F&V. -When mothers were fully or partially employed, families consumed more portions of F&V. |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Annunziata A., Vecchio R., Kraus A. Factors affecting parents’ choices of functional foods targeted for children. International Journal of Consumer Studies. Special Issue: Children as Consumers. 2016. Volume 40, Issue 5. Pages 527-535.

- Kanellos P. Investigation of the Corinthian raisin as a "Functional" food of the Mediterranean diet. Doctoral thesis. Harokopio University. School of health and education sciences. Department of Science of Diet – Nutrition. Athens, Greece (2016).

- Küster-Boludaa I., Vidal-Capilla I. Consumer attitudes in the election of functional foods. Spanish Journal of Marketing – ESIC. 2017. Volume 2, Issue S1. Pages 65-79.

- Konstantinidi M., Koutelidakis A. Functional Foods and Bioactive Compounds: A Review of Its Possible Role on Weight Management and Obesity’s Metabolic Consequences. Medicines (Basel). 2019. Volume 6. Issue 3. Page 94.

- Kaprelyants L., Yegorova A., Trufkati L., Pozhitkova L., Functional Foods: Prospects in Ukraine. Food Science and Technology. 2019. Volume 13, Issue 2. Pages 15-23.

- Weiss P. J. Parental Awareness, Consumption And Feeding Practices Of Functional Foods. Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 596. Master of Science in the Department of Nutrition and Hospitality Management, University of Mississippi, USA (2016).

- Ozen A. E., Pons A., Tur J. A. Worldwide consumption of functional foods: a systematic review. Nutrition Reviews. 2012. Volume 70, Issue 8. Pages 472–481.

- Kraus, A. Factors influencing the decisions to buy and consume functional food. British Food Journal. 2015. Volume 117, Issue 6, Pages 1622 – 1636.

- Kraus A., Annunziata A., Vecchio R. Sociodemographic Factors Differentiating the Consumer and the Motivations for Functional Food Consumption. Journal of the American College of Nutrition. 2017. Volume 36, Issue 2. Pages 116-126.

- Badu-Gyan F., Owusu V. Consumer willingness to pay a premium for a functional food in Ghana. Applied Studies in Agribusiness and Commerce. 2017. Volume 11. Issue 1-2. Pages 51-60.

- Carrillo E., Prado-Gascó V., Fiszman S., Varela P. Why buying functional foods? Understanding spending behaviour through structural equation modelling. Food Research International. 2013. Volume 50, Issue 1. Pages 361-368.

- Savage J. S., Fisher J. O., Birch L. L. Parental Influence on Eating Behavior Conception to Adolescence. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 2007. Volume 35, Issue 1. Pages 22–34.

- Romanos - Nanclares A., Zazpe I., Santiago S., Marín L., Rico-Campà A. Martín-Calvo N. Influence of Parental Healthy-Eating Attitudes and Nutritional Knowledge on Nutritional Adequacy and Diet Quality among Preschoolers: The SENDO Project. Nutrients. 2018. Volume 10, Issue 12. Page 1875.

- Vollmer R. L., Baietto J. Practices and preferences: Exploring the relationships between food-related parenting practices and child food preferences for high fat and/or sugar foods, fruits, and vegetables. Appetite. 2017. Volume, Issue 1. Pages 134-140.

- Hart L. M., Damiano S. R., Cornell C., Paxton S. J. What parents know and want to learn about healthy eating and body image in preschool children: a triangulated qualitative study with parents and Early Childhood Professionals. BMC Public Health. 2015. 15:596.

- Kazi E. H., Kazi F. H., Revethy T. Relationships between parents’ academic backgrounds and incomes and building students’ healthy eating habits. PeerJ. 2018; 6: e4563.

- Zarnowiecki D., Ball K., Parletta N., Dollman J. Describing socioeconomic gradients in children’s diets – does the socioeconomic indicator used matter? International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2014. Volume 11. Article number: 44.

- Tornaritis M. J., Philippou E., Hadjigeorgiou C., Kourides Y. A., Panayi A., Savvas S. A study of the dietary intake of Cypriot children and adolescents aged 6–18 years and the association of mother’s educational status and children’s weight status on adherence to nutritional recommendations. BMC Public Health. 2014, Volume 14, Article number: 13.

- Krystallis, A., Chrysochou, P. Do health claims and prior awareness influence consumers’ preferences for unhealthy foods? The case of functional children’s snacks. Agribusiness. 2012. Volume 28, Issue 1. Pages 86-102.

- Rahmawaty S., Charlton K., Lyons-Wall P., Meyer B. J. Factors that influence consumption of fish and omega-3-enriched foods: A survey of Australian families with young children. Nutrition & Dietetics, Journal of Dietitians Australia. 2013. Volume 70, Issue 4. Pages 286–293.

- DeLeon O., Chang Y., Roseman M. G. Relationship between Income and Parents Including Functional Foods in Their Children’s Diet. Journal of the academy of nutrition and dietetics, Poster Session: Wellness and Public Health, September 2015 Suppl 2—Abstracts Volume 115, Number 9S. Page A-89.

- Mohamad H., Mirosa M., Bremer P., Oey I. A Qualitative Study of Malaysian Parents’ Purchase Intention of Functional Weaning Foods using the Theory of Planned Behavior. Journal of Food Products Marketing. 2019. Volume 25, Issue 2. Pages 187–206.

- Lazzeri G., Pammolli A., Azzolini E., Simi R., Meoni V., Rudolph de Wet D., Giacchi M. V. Association between fruits and vegetables intake and frequency of breakfast and snacks consumption: a cross-sectional study. Nutrition Journal. 2013. Volume 27, Issue 12. Page 123.

- Lynch C., Kristjansdottir A. G., Te Velde S. J., Lien N., Roos E., Thorsdottir I., Krawinkel M., Vaz de Almeida M. D., Papadaki A., Ribic C. H., Petrova S., Ehrenblad B., Halldorsson T. I., Poortvliet E., Yngve A. Fruit and vegetable consumption in a sample of 11-year-old children in ten European countries--the PRO GREENS cross-sectional survey. Public Health Nutrition. 2014 Volume 17, Issue 11. Pages 2436-44.

- Coto J., Pulgaron E. R., Graziano P. A., Bagner D. M., Villa M., Malik J. A., Delamater A. M. Parents as Role Models: Associations Between Parent and Young Children’s Weight, Dietary Intake, and Physical Activity in a Minority Sample. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2019. Volume 23, Issue 7. Pages 943-950.

- Benetou V., Kanellopoulou A., Kanavou E., Fotiou A., Stavrou M., Richardson C., Orfanos P., Kokkevi A. Diet-Related Behaviors and Diet Quality among School-Aged Adolescents Living in Greece. Nutrients. 2020. Volume 12, Issue 12. Page 3804.

- Malisova O., Vlassopoulos A., Kandyliari A., Panagodimou E., Kapsokefalou M. Dietary Intake and Lifestyle Habits of Children Aged 10-12 Years Enrolled in the School Lunch Program in Greece: A Cross Sectional Analysis. Nutrients. 2021. Volume 13, Issue 2. Page 493.

- Papamichael M. M., Moschonis G., Mavrogianni C., Liatis S., Makrilakis K., Cardon G., De Vylder F., Kivelä J., Barrantes P. F., Imre R., Moreno L., Iotova V., Usheva N., Tankova T., Manios Y.; Feel4Diabetes-Study Group. Fathers’ daily intake of fruit and vegetables is positively associated with children’s fruit and vegetable consumption patterns in Europe: The Feel4Diabetes Study. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics. 2022. Volume 35, Issue 2. Pages 337-349.

- Pereira B., Silva C., Núñez J. C., Rosário P., Magalhães P. "More Than Buying Extra Fruits and Veggies, Please Hide the Fats and Sugars": Children’s Diet Latent Profiles and Family-Related Factors. Nutrients. 2021. Volume 13, Issue 7. Page 2403.

- Hamner H.C., Dooyema C. A., Blanck H. M., Ayala R. F., Jones J. R., Ghandour R. M., Petersen R. Fruit, Vegetable, and Sugar - Sweetened Beverage Intake Among Young Children, by State - United States 2021. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2023. Volume 72, Issue 7. Pages 165-170.

- Shrestha N., Banstola S., Sharma B. Fruit and vegetable consumption among young school children in Pokhara, Kaski: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Gandaki Medical College-Nepal. 2023. Volume 16, Issue 1. Pages 58-63.

- Eliason J., Acciai F., DeWeese R. S., López S. V., Vachaspati P. O. Children’s Consumption Patterns and Their Parent’s Perception of a Healthy Diet. Nutrients. 2020. Volume 12, Issue 8. Page 2322.

- Charneca S., Gomes A. I., Branco D., Guerreiro T., Barros L., Sousa J. Intake of added sugar, fruits, vegetables, and legumes of Portuguese preschool children: Baseline data from SmartFeeding4Kids randomized controlled trial participants. Frontiers in Nutrition. 2023. Volume 10.

- Draxten M., Fulkerson J. A., Friend S., Flattum C. F., Schow R. Parental role modeling of fruits and vegetables at meals and snacks is associated with children’s adequate consumption. Appetite. 2014. Volume 78. Pages 1-7.

- Wolnicka K., Taraszewska M. A., Schuetz J. J., Jarosz M. Factors within the family environment such as parents’ dietary habits and fruit and vegetable availability have the greatest influence on fruit and vegetable consumption by Polish children. Public Health Nutrition. 2015. Volume 18, Issue 15. Pages 2705-11.

- Jackson J. A., Smit E., Manore M. M., John D., Gunter K. The Family-Home Nutrition Environment and Dietary Intake in Rural Children. Nutrients. 2015. Volume 7, Issue 12. Pages 9707–9720.

- Mantziki K., Renders C. M., Vassilopoulos A., Radulian G., Borys J. M., Plessis H., Gregório M. J., Graça P., Henauw S., Handjiev S., Visscher T. L., Seidell J. C. Inequalities in energy-balance related behaviours and family environmental determinants in European children: changes and sustainability within the EPHE evaluation study. International Journal for Equity in Health. 2016. Volume 15, Issue 1. Page 160.

- Schoeppe S., Trost S. G. Maternal and paternal support for physical activity and healthy eating in preschool children: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2015. Volume 28 Issue 15. Page 971.

- Yannakoulia M., Lykou A., Kastorini C. M., Eirini Papasaranti S., Petralias A., Veloudaki A., Linos A.; DIATROFI Program Research Team. Socio-economic and lifestyle parameters associated with diet quality of children and adolescents using classification and regression tree analysis: the DIATROFI study. Public Health Nutr. 2016. Volume 19, Issue 2. Pages 339-47.

- Etayo P. M., Flores P., Santabarbara J., Iglesia I., Cardon G., Iotova V., Koletzko B., Androutsos O., Kotowska A., Manios Y., Paw Chin M., Moreno L. A. Parental role modelling and fruits and vegetables intake in European preschoolers: ToyBox-study. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. Malnutrition in an Obese World: European Perspectives. Volume 79 - Issue OCE2 – 2020. 13th European Nutrition Conference, FENS 2019, 15–18 October 2019.

- Linde J. A., Dehmer M. L. H., Lee J., Friend S., Flattum C., Arcan C., Fulkerson J. A. Associations of parent dietary role modeling with children’s diet quality in a rural setting: Baseline data from the NU-HOME study. Appetite. 2022. Volume 174.

- LeBlanc J., Ward S., LeBlanc C. P. The Association Between Adolescents’ Food Literacy, Vegetable and Fruit Consumption, and Other Eating Behaviors. Health Education & Behavior. 2022. Volume 49, Issue 4. Pages 603-612.

- Hong S. A., Piaseu N. Prevalence and determinants of sufficient fruit and vegetable consumption among primary school children in Nakhon Pathom, Thailand. Nutrition Research and Practice. 2017. Volume 11, Issue 2. Pages 130-138.

- Groele B., Głabska D., Gutkowska K., Guzek D. Mother-Related Determinants of Children At-Home Fruit and Vegetable Dietary Patterns in a Polish National Sample. Sustainability. 2019, Volume 11, Issue 12. Page 3398.

- Quezada-Sánchez A.D., Shamah-Levy T., Mundo-Rosas V. Socioeconomic characteristics of mothers and their relationship with dietary diversity and food group consumption of their children. Nutrition & Dietetics, Journal of Dietitians Australia. 2020. Volume 77, Issue 4. Pages 467-476.

- Barrantes P. F., Mavrogianni C., Iglesia I., Mahmood L., Willems R., Cardon G., Vylder F., Liatis S., Makrilakis K., Martinez R., Schwarz P., Rurik I., Antal E., Iotova V., Tsochev K., Chakarova N., Kivelä J., Wikström K., Manios Y., Moreno L.; Feel4Diabetes-study Group. Can food parenting practices explain the association between parental education and children’s food intake? The Feel4Diabetes-study. Public Health Nutrition. 2022. Volume 25, Issue 10. Pages 1-14.

- Boelens M., Raat H.,a Wijtzes A. I., Schouten G. M., Windhorst D. A., Jansen W. Associations of socioeconomic status indicators and migrant status with risk of a low vegetable and fruit consumption in children. SSM Population Health. 2022. Volume 17. Article number 101039.

- Serasinghe N., Vepsäläinen H., Lehto R., Abdollahi A. M., Erkkola M., Roos E., Ray C. Associations between socioeconomic status, home food availability, parental role-modeling, and children’s fruit and vegetable consumption: a mediation analysis. BMC Public Health. 2023. Volume 23, Issue 1. Article number 1037.

- Shrestha N., Banstola S., Sharma B. Fruit and vegetable consumption among young school children in Pokhara, Kaski: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Gandaki Medical College-Nepal. 2023. Volume 16, Issue 1. Pages 58-63.

- Siopis G., Moschonis G., Reppas K., Iotova V., Bazdarska Y., Chakurova N., Rurik I., Radó A., Cardon G., De Craemer M., Wikström K., Valve P., Moreno L. A., Etayo P. D. M., Makrilakis K., Liatis S., Manios Y., On Behalf Of The Feel Diabetes-Study Group. The Emerging Prevalence of Obesity within Families in Europe and its Associations with Family Socio-Demographic Characteristics and Lifestyle Factors; A Cross-Sectional Analysis of Baseline Data from the Feel4Diabetes Study. Nutrients. 2023. Volume 15, Issue 5. Page 1283.

- Attorp A., Scott J. E., Yew A. C., Rhodes R. E., Barr S. I., Naylor P. J. Associations between socioeconomic, parental and home environment factors and fruit and vegetable consumption of children in grades five and six in British Columbia, Canada. BMC Public Health. 2014. Volume 14. Article number 150.

- de Jong E., Visscher T. L. S., HiraSing R. A., Seidell J. C., Renders C. M. Home environmental determinants of children’s fruit and vegetable consumption across different SES backgrounds. Pediatric Obesity. 2015. Volume 10, Issue 2. Pages 134-40.

- Lehto E., Ray C., Velde S., Petrova S., Duleva V., Krawinkel M., Behrendt I., Papadaki A., Kristjansdottir A., Thorsdottir I., Yngve A., Lien N., Lynch C., Ehrenblad B., Vaz de Almeida M. D., Ribic C. H., Simčic I., Roos E. Mediation of parental educational level on fruit and vegetable intake among schoolchildren in ten European countries. Public Health Nutrition. 2015. Volume 18, Issue 1. Pages 89-99.

- Richards R., Reicks, M., Wong S. S., Gunther C., Cluskey M., Ballejos M. S., Watters C. Perceptions of How Parents of Early Adolescents Will Personally Benefit From Calcium-Rich Food and Beverage Parenting Practices. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 2014. Volume 46, Issue 6. Pages 595–601.

- Birbilis M., Moschonis G., Mougios V., Manios, Y. Obesity in adolescence is associated with perinatal risk factors, parental BMI and sociodemographic characteristics. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2013. Volume 67. Pages 115-121.

- DeLeon O., Roseman M.G., Chang Y. Relationship between Race/Ethnicity and Parents Including Functional Foods in Their Children’s Diet. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2016. Volume 116. Issue 9. Supplement A-939.

- Campbell K. J., Abbott G., Spence A. C., Crawford D. A. McNaughton S. A., Ball K. Home food availability mediates associations between mothers’ nutrition knowledge and child diet. Appetite, 2013. Volume 71. Pages 1–6.

- Rex M. S., Kopetsky A., Bodt B., Robson M. S. Relationships Among the Physical and Social Home Food Environments, Dietary Intake, and Diet Quality in Mothers and Children. Journal of the Academy of nutrition and dietetics. 2021. Volume 121, Issue 10. Pages 2013-2020.

- Vepsäläinen H., Nevalainen J., Fogelholm M., Korkalo L., Roos E., Ray C., Erkkola M.; DAGIS consortium group. Like parent, like child? Dietary resemblance in families. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2018. Volume 15, Issue 1. Article number 62.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).