1. Introduction

The International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Group (IADPSG) in 2010, based on the results of the Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO) study [

1] has recommended a new method of screening and diagnosis of gestational diabetes (GDM), underljing the importance to diagnose the “Overt Diabetes” defined as “an

hyperglycemia first recognized during pregnancy which meets the diagnostic threshold of diabetes in non-pregnant adult “[

2].Overt diabetes in pregnancy is a severe form of hyperglycemia so efforts must be done to recognize as soon as possible this condition in order to reduce the negative maternal and fetal outcome related to it [

3,

4,

5].

Most of the studies published in literature compare the pregnancy outcomes of pregnant women affected by overt diabetes to those of women affected by gestational diabetes showing a worse maternal and fetal outcomes in the former compared to the latter [

6]. Type 2 diabetes in pregnancy is increasing accounting for 30-50% of pregesational diabetes and is related to adverse maternal and fetal outcomes [

7,

8]. So we think of interest to compare pregnancy outcomes in women affected by overt diabetes to those with pregestational type 2 diabetes.

2. Materials and Methods

We retrospectively evaluated pregnant women with type 2 diabetes and overt diabetes who had at least one pregnancy followed in the period 2010-2022 at the Diabetic Care Unit of Padova. Women with type 1, latent autoimmune diabetes of the adult (LADA),maturity onset diabetes of the youth ( MODY) and GDM were excluded from the study.Overt diabetes was diagnosed according to ADA [

3] and World Health Organization criteria ( fasting plasma glucose ≥ 126 mg/dl or glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels ≥ 6.5%[

9].Data were estracted from electronic medical records.During the first pregnancy visit, physiological and obstetric history were collected, which provided information regarding pre-pregnancy weight and BMI, pregnancy planning, date of last menstruation, parity, previous GDM, and pregnancy outcome of previous pregnancies.The values of glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), fasting and post-prandial glycaemia, microalbuminuria, systolic and diastolic blood pressure during pregnancy were collected. As for chronic diabetes complications, retinopathy was assessed based on the ophthalmological control, nephropathy based on albuminuria values and was considered present if the urinary albumin/creatinine ratio exceeded 30 mg/g. Patients were considered to have chronic hypertension when this was reported in the patient's medical history or if they were taking hypertensive drugs before. Neuropathy was assessed by clinical evaluation of symptoms and tests for autonomic neuropathy disfunction. At their first appointment and at the follow up visits at the Diabetic Care Unit women received a multidisciplinary team consisting of a diabetologist, a dietician and a nurse. They were counseled about maternal and fetal risks related to diabetes, received an individualized diet, were educated to perform self monitoring blood glucose (fasting and 1 h after breakfast, lunch and dinner), insulin teraphy and underwent periodic clinical and biochemical evaluations. As for maternal outcomes, miscarriages, mode and time of delivery, complications during labor and delivery, preeclampsia were recorded, for neonatal outcomes weight, length at birth, shoulder dystocia, hypoglycemia, jaundice,hypocalcemia, respiratory distress and congenital malformations were recorded.

Height was measured at the first appointment and weight at each visit, body mass index (BMI)was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height (h/m2).

The newborn were classified as large for gestational age (LGA) if their birth weight was >90

th percentile, or small for gestational age ( SGA) if it was <10

th percentile, based on standard growth and development tables for the Italian population[

10].

Plasma glucose levels were measured using the glucose oxidase method[

11].HbA1c was measured by a standardized HPLC method IFCC aligned [

12].

Statistical evaluation

The data were processed with the IBM SPSS 25 statistical programs. Continuous quantitative variables are expressed as means ± standard deviations, and were compared with Student’s t-test. No parametric data are expressed as % and analyzed with X2 tests. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistical significant.

3. Results

We analyzed 83 pregnancies in 68 Type 2 diabetic patients (T2DM); overt diabetes (OT2DM ) was diagnosed in 21.7% of pregnancies (18/83). Of note, 95% of patients with overt diabetes were immigrate mainly from South East Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa. As regards clinical and metabolic characteristics the two groups are comparable in terms of age, pre-pregnancy BMI, chronic hypertension and previous pregnancies. Chronic diabetic complications were higher in Type 2DM women with respect to OT2DM women, even if not significant (

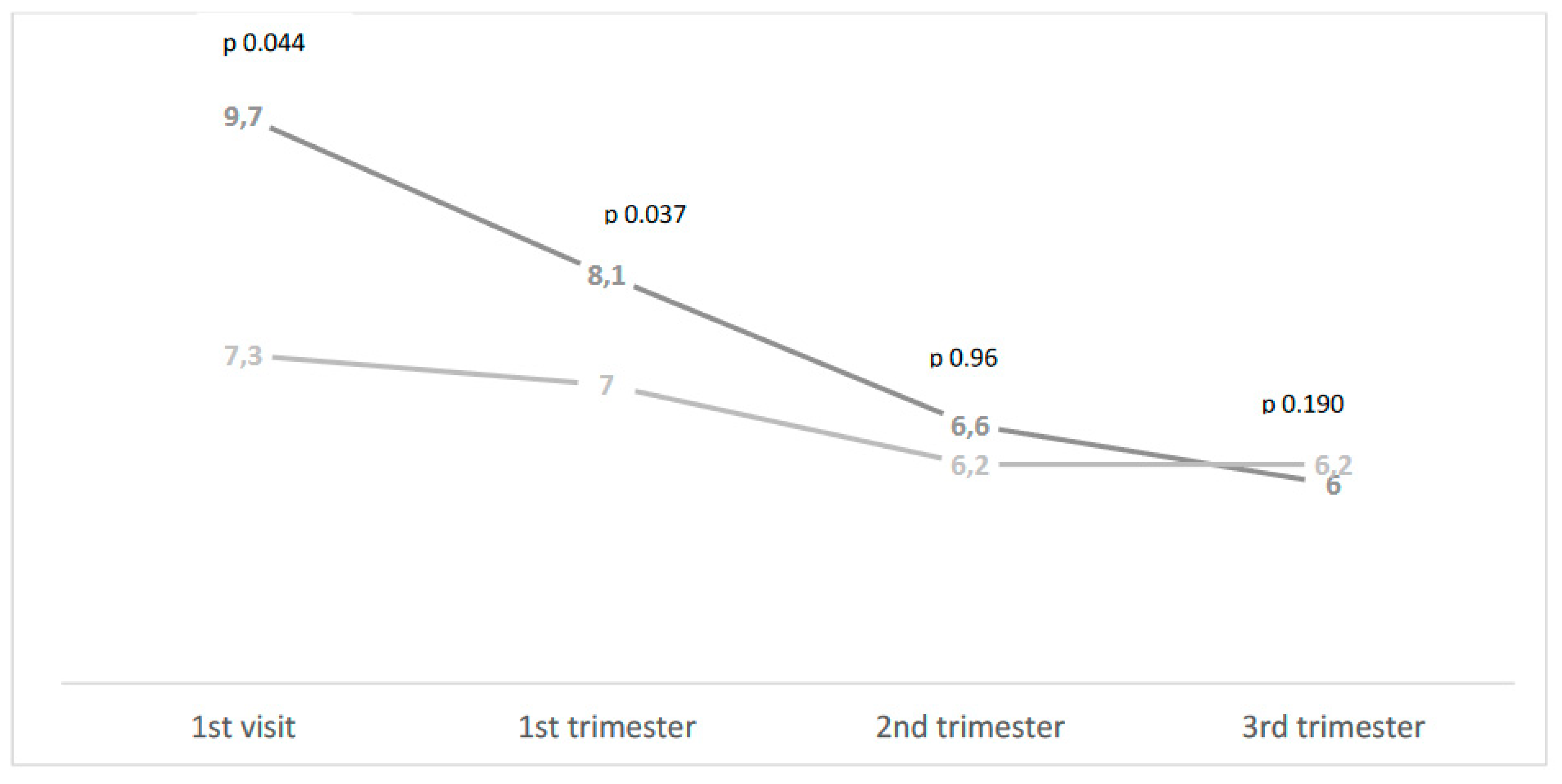

Table 1). On the other hand, the two groups differed significantly in terms of glycemic control (HbA1c levels) at the first visit and in the first trimester that were worst in OT2DM women(HbA1c 9.7± 3.1% vs 7.3% ± 2.3%, p< 0.044 at first visit; 8.1±1.9%, and 7.0±1.6%, p< 0.037 in the first trimester), (Figure ).

As for maternal outcomes, miscarriage rate was higher, even not significantly, in OT2DM women respect to T2DM ones, but gestational hypertension rate was higher in T2DM women (

Table 1).

As for fetal outcomes, congenital malformations were more frequent, even if at the limit of significance, in OT2DM women with respect to T2DM ones (11.1% vs 7.7%), while the rate of the other fetal complications were higher in T2DM women. No significant differences have been found in LGA rate (

Table 1).

Figure 1.

HbA1c levels during pregnancy in OT2D (dark grey) and T2DM (light grey).

Figure 1.

HbA1c levels during pregnancy in OT2D (dark grey) and T2DM (light grey).

4. Discussion

The most of the studies published in literature in order to better define the physiophatological mean of overt type 2 diabetes compare this pathology to GDM. In a case control study Agha-Jaffar et all showed an higher frequency of hypertensive disorders and an higher frequency on insulin treatment in OT2DM compared to GDM ones and pointed the fact that OT2DM is phenotypically a type 2 diabetes mellitus (13). In a multi-ethnic cohort in Spain pregnant women with OT2DM showed worse obstetric outcomes with respect to GDM ones and this was present mainly in women from ethnic minorities ( 14). In a recent literature search, that has taken into consideration articles up to 2022, a worse maternal and fetal outcomes has been evidenced in OT2 DM with respect to GDM women, even if different diagnostic criteria have been utilized to diagnose OT2 DM in the reported studies (6).

In our study, that has compared the maternal and fetal outcomes in overt type 2 diabetic pregnant women to pre pregnancy type 2 diabetic ones, the main finding is that OT2DM show an higher frequency of congenital malformations with respect to T2DM. This finding can be explained by the worse glycemic control observed in overt type 2 pregnant women and by the fact that none of these women planned their pregnancy. In a case control study that has evaluated 414 T2DM and 2014 OT2DM even if women with OT2 DM arrived to specialized prenatal care center at the third trimester of pregnancy while those with T2DM at the first trimester no differences in maternal and fetal outcomes have been found also considering congenital malformations; it is to notice that mean values of HbA1c at booking were no different and no bad in the two groups ( 7.2 vs 7.4 %),and that 70% of women were white (15).In a retrospective study comparing 120 OT2DM pregnant women and 86 T2DM, 75% of caucasian race, even if 55% of OT2DM women arrived late at the specialized prenatal care center no significant differences have been found in the two groups regarding maternal an fetal outcomes (16). It is to notice however that OT2 DM have significantly lower values of HbA1c compared to T2DM in pre pregnancy and in the first trimester and that no data are reported on congenital malformations. Poor glycemic control in the preconception phase (17) and the frequent coexsistence of obesity (7) are well known risk factors in determining a worse neonatal outcome in type 2 diabetes pregnant women. In our cohort no difference in the frequency of obesity have been found but, as before mentioned, the levels of HbA1c were higher in overt type 2 diabetes with respect to type 2 diabetic ones. Preconception care is of key importance to reduce maternal and fetal complications in pregnancy complicated by pregestational diabetes so the fact that women with overt type 2 diabetes no planned the pregnancy can explain the high frequency of congenital malformations(18). The most of the pregnant women with overt type 2 diabetes in our cohort do not known to have diabetes and even if 78% of them have had a gestational diabetes treated in 43% of cases with insulin none of the women underwent a post partum evaluation of glucose tolerance. The high frequency in our study of immigrate women well explain the scarce aderence to post partum follow up (19) and the poor attendance to antenatal pregnancy care units (20). The strengts of the study are the well-characterized cohort of women followed during all pregnancy by the same multidisciplinary team. Limits are the scarce number of patients evaluated so that some differences are at the limits of significance.

In conclusion it is essential to utilize procedure for diabetes screen in women of childbearing age, not only at the beginning of pregnancy, but also in the preconception phase when strong risk factors for overt diabetes are present, such as high BMI, previous glycemic disorders and high-risk ethnicity.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Province of Padova resolution n 1248 Patients give their informed consent.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- HAPO Study Cooperative Research Group. The Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO) Study. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2002,78(1):69-77. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups Consensus Panel; Metzger BE, Gabbe SG, Persson B, Buchanan TA, Catalano PA, Damm Pet al. International association of diabetes and pregnancy study groups recommendations on the diagnosis and classification of hyperglycemia in pregnancy. Diabetes Care.2010, 33(3):676-82. PMCID: PMC2827530. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care 2023, 46(Suppl 1):S19-S40. [CrossRef]

- Lapolla, A., Metzger B.E.. The post-HAPO situation with gestational diabetes: the bright and dark sides. Acta Diabetol.2018, 55(9):885-892. Epub 2018 May 4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, T., Ross G.P., Jalaludin B.B., Flack J.R.. The clinical significance of overt diabetes in pregnancy. Diabet Med. 2013,Apr;30(4):468-74. [CrossRef]

- Goyal A., Gupta Y., Tandon N.. Overt Diabetes in Pregnancy. Diabetes Ther. 2022, Apr;13(4):589-600. Epub 2022 Feb 2. [CrossRef]

- Dalfrà, M.G., Burlina S., Lapolla A.. Pregnancy and type 2 diabetes: unmet goals.Endocrines 2023, 4:366-377. [CrossRef]

- Raets, L., Ingelbrecht A., Benhalima K.. Management of type 2 diabetes in pregnancy: a narrative review. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023,Jul 21;14:1193271. PMCID: PMC10402739. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Diagnostic criteria and classification of hyperglycemia first detected in pregnancy. A World Health Organization Guidelines. Diab Res Clin Pract 2014, 103 (3): 341-63. [CrossRef]

- Parazzini, F., Cortinovis I., Bortolus R., Fedele L., Recarli A. Weight at birth by gestational age in Italy. Hum Reproduct.1995, 10:1862-63. [CrossRef]

- Huggett AS, Nixon DA. Use of glucoseoxidase, peroxidase, and O-dianisidine in determination of blood and urinary glucose.Lancet 1957, 273(6991):368-70. [CrossRef]

- Mosca, A., Paleari R.,Dalfrà MG., DiCianni G., Cuccuru I., Pellegrini G. et al. Reference intervals for hemoglobin A1c in pregnant women:data from an Italian multicenter study. Clin Chem. 52:1138-1143 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Agha-Jaffar, R., Oliver N.S., Kostoula M., Godsland I.F., Yu C. et al. Hyperglycemia recognised in early pregnancy is phenotypically type 2 diabetes mellitus not gestational diabetes mellitus: a case control study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 33(23):3977-3983. (2020). Epub 2019 Mar 26. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mañé, L., Flores-Le Roux J.A., Benaiges D., Chillarón J.J., Prados M. et al. Impact of overt diabetes diagnosed in pregnancy in a multi-ethnic cohort in Spain. Gynecol Endocrinol. 35(4):332-336 (2019). Epub 2018 Oct 17. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oppermann, M.L., Campos M.A., Hirakata V.N., Reichelt A.J.. Overt diabetes imposes a comparable burden on outcomes as pregestational diabetes: a cohort study. Diabetol Metab Syndr.14(1):177 (2022). PMCID: PMC9685976. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiller, T., Barak Où., Winter Shafran Y., Barak Sacagiu M., Cohen L. et al. Prediabetes in pregnancy - follow-up, treatment, and outcomes compared to overt pregestational diabetes. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med.36(1):2191153 (2023). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lapolla, A., Dalfrà M.G., Fedele D. Pregnancy complicated by diabetes: what is the best level of HbA1c for conception? Acta Diabetol 47(3):187-92 (2010). Epub 2010 May 26. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahabi, H.A., Fayed A., Esmaeil S., Elmorshedy H., Titi M.A. et al.Systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness of pre-pregnancy care for women with diabetes for improving maternal and perinatal outcomes. PLoS One 15(8):e0237571 (2020). PMCID: PMC7433888. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalfrà, M.G., Burlina S., Del Vescovo G.G., Anti F., Lapolla A. Adherence to a follow-up program after gestational diabetes. Acta Diabetol.57(12):1473-1480 (2020). Epub 2020 Aug 1. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez-Rivas, E., Flores-Le Roux J.A., Benaiges D., Sagarra E., Chillaron J.J. et al. Gestational diabetes in a multiethnic population of Spain: clinical characteristics and perinatal outcomes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 100(2):215-21 (2013). Epub 2013 Mar 26. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).