2. Biomechanics

The SCJ is part of a group of five articulations that influences the pattern of movement of the shoulder-girdle. It is defined as a synovial and diarthrodial joint with a saddle-like shape; moreover, it is the only skeletal articulation between axial skeleton and upper limb. The clavicle articulates with the reciprocal notch of the sternum and the superior surface of the first costal cartilage; on the other side, the joint is concave in the vertical axis and convex in the anteroposterior one; the articular surfaces are not fully suitable to each other, consequently they are divided by a flat meniscus, or an articular disc, to improve the bone congruence. As a result of the sella turcica-like shape of the joint, the disc has mobility among the anteroposterior and vertical axis [

6]. Raising and lowering movements occur between the articular disk and the clavicle, whereas protraction and retraction occur between the articular disc and the sternum [

7]. Since SCJ is a synovial joint, it is often involved in various other pathologies, such as rheumatoid arthritis, gout and Reiter’s syndrome [

8].

Despite its restricted symptomatology, we are describing a type of injury that impacts on the scapulothoracic and glenohumeral rhythm, and its treatment restores normal range of motion (ROM) of the shoulder-girdle. The SCJ achieves an angle of 35° of movement, both in coronal and horizontal planes, during the shoulder abduction along with an angle of 45° of rotation in its long axis [

5]. The ligaments of SCJ are represented by the anterior sterno-clavicular ligament, the posterior sterno-clavicular ligament, the costo-clavicular ligament and the interclavicular ligament [

10].

The SCJ represents one of the most stable joints in the human body, due to the strength of its surrounding ligaments, accounting for only about 3% of all shoulder dislocations [

11]. The joint is divided in two parts by a cartilage disc, which is linked to the clavicle and the first rib; the joint’s stability is maintained by four ligaments, as we mentioned above, which helps the articular disc as well as anterior and posterior capsules [

12]. Without these structures the SCJ would be very unstable because the articular part of the clavicle and sternum do not come in a perfect articular contact with each other [

11,

13]. The anterior sterno-clavicular ligament is broad and it extends from the antero-superior surface of medial end of the clavicle to the upper anterior edge of the manubrium and the first costal cartilage. The posterior sterno-clavicular ligament extends from the posterior aspect of the sternal end of the clavicle to the postero-superior aspect of the manubrium. The posterior ligament confers primary stability to the joint, which is supplemented by the rest of the ligaments. The interclavicular ligament extends between the medial ends of the clavicle and it is continuous with the deep cervical fascia superiorly. The costo-clavicular ligament is shaped like a short flattened, inverted cone; it has two laminae on the anterior and posterior aspects of the clavicle [

6]. The anterior lamina is lateral and attached to the upper aspect of the first rib and the costal cartilage inferiorly, and the inferior aspect of the medial portion of the clavicle superiorly. The posterior lamina is medial and attached to the first rib and costal cartilage, likewise the anterior lamina. As for the capsules, the anterior capsule prevents anterior translation, while the posterior one acts on avoiding anterior and posterior translation. Therefore, posterior dislocations are less frequent and require major injuries and higher forces compared to anterior dislocations [

14]. This event may show up also without any trauma in case of ligamentous laxity which needs to be treated in a conservative way [

15]. Another reason that causes a higher frequency of anterior dislocations is that anterolateral blows are more common than postero-lateral ones, furthermore anterior capsule and the ligament is thinner [

16].

The SCJ has a late fusion of the epiphyseal nucleus at an age between 22 and 25 years old [

1]. Proximal clavicle physeal fracture-separation in young patients could mimic a sterno-clavicular dislocation in up to 50% of cases [

2,

3,

4]. Few studies demonstrate that the ossification of medial epiphysis of the clavicle occurs frequently at approximately 18 to 20 years of age, while the closure of the physis has not happened yet [

7,

8,

9]. As a result, many cases of sterno-clavicular dislocations may actually be injuries of the clavicular physis.

3. Clinical Presentation

The SCJ injuries are usually caused by direct or indirect high forces acting on the shoulder. These pathology are divided into three categories according to the severity: grade 1 includes simple sprains with partial ligament tear, but without any instability observed; grade 2 comprises anterior or posterior subluxations caused by complete rupture of the SC ligament; finally, grade 3 includes complete dislocations of the SCJ with complete tear of all ligaments [

12]. It is very common that grade 3 injuries hesitate in unstable SCJs, that could not be treated with closed reduction but the need of an open reduction to repair the broken structures.

Sometimes the ligaments’ attachment can be very prominent, but this should not be mistaken for pathology. Forces are transmitted through the clavicle to ligaments, on the medial aspect; the clavicle will more often break before the surrounding ligaments’ fail.

Vascular supply to the SCJ comes from the suprascapular and the internal thoracic arteries. Nerve supply originates from the medial suprascapular nerve and some branches from the subclavius. The brachiocephalic trunk lies directly posterior to the SCJ, represented by the common carotid artery and the internal jugular vein.

Clinical presentation is often characterised by neck and shoulder pain, deformity of the SCJ with a palpable defect. Complications may be very dangerous, due to the presence of noble structures in the immediate proximity to the joint: disorders referred to neurological structures (brachial plexus, phrenic and vagus nerves) and/or vascular ones (compression or laceration of subclavians, internal jugulars, internal thoracics, brachiocephalic vessels), pneumothorax, myocardial conduction abnormalities, esophagus or trachea rupture, mediastinal compression, and thoracic outlet syndrome. In case of complications we can have a wider symptomatology with the possible presence of cyanosis, choking, cervical bruit, tracheal hematoma, stridor, dyspnea and respiratory distress, dysphagia, hoarseness, odynophagia, compromised circulation to the arm, diaphragmatic paralysis and even death [

5,

6,

7].

Moreover, adjacent structures that overlap the SCJ make assessment and interpretation of routine chest radiographs very difficult. Even with special views, as Hobbs and Rockwood, the differential diagnosis between dislocation and physeal injury or between anterior and posterior dislocation may not be so immediate [

5]. Consequently, a computed tomography (CT) scan is a better option to get a three-dimensional understanding of the SCJ and we can also check all mediastinal structures, if intravenous contrast is administered. On magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the articular surfaces and intra-articular disc are better seen in coronal sequences, whereas axial sequences depict anterior and posterior capsules and ligaments. The sagittal sequences are useful in assessing costo-clavicular ligaments [

3].

The posterior dislocation has to always be reduced due to the risk of late sequelae [

17]. When a posterior dislocation comes to the attention of orthopaedics in less than 48 hours a closed reduction should be attempted under general anesthesia, positioning the involved arm in abduction, then tractioning and extending carefully. If this manoeuvre results effectively, a follow-up CT scan can be indicated to avoid any recurrent dislocations. On the other hand, both failure of closed reduction and presentation over 48 hours (more frequent, due to aforementioned difficulties in differential diagnosis) require an open reduction. In fact, a closed reduction after 2 days has a high probability to be in vain [

18].

4. Our Experience

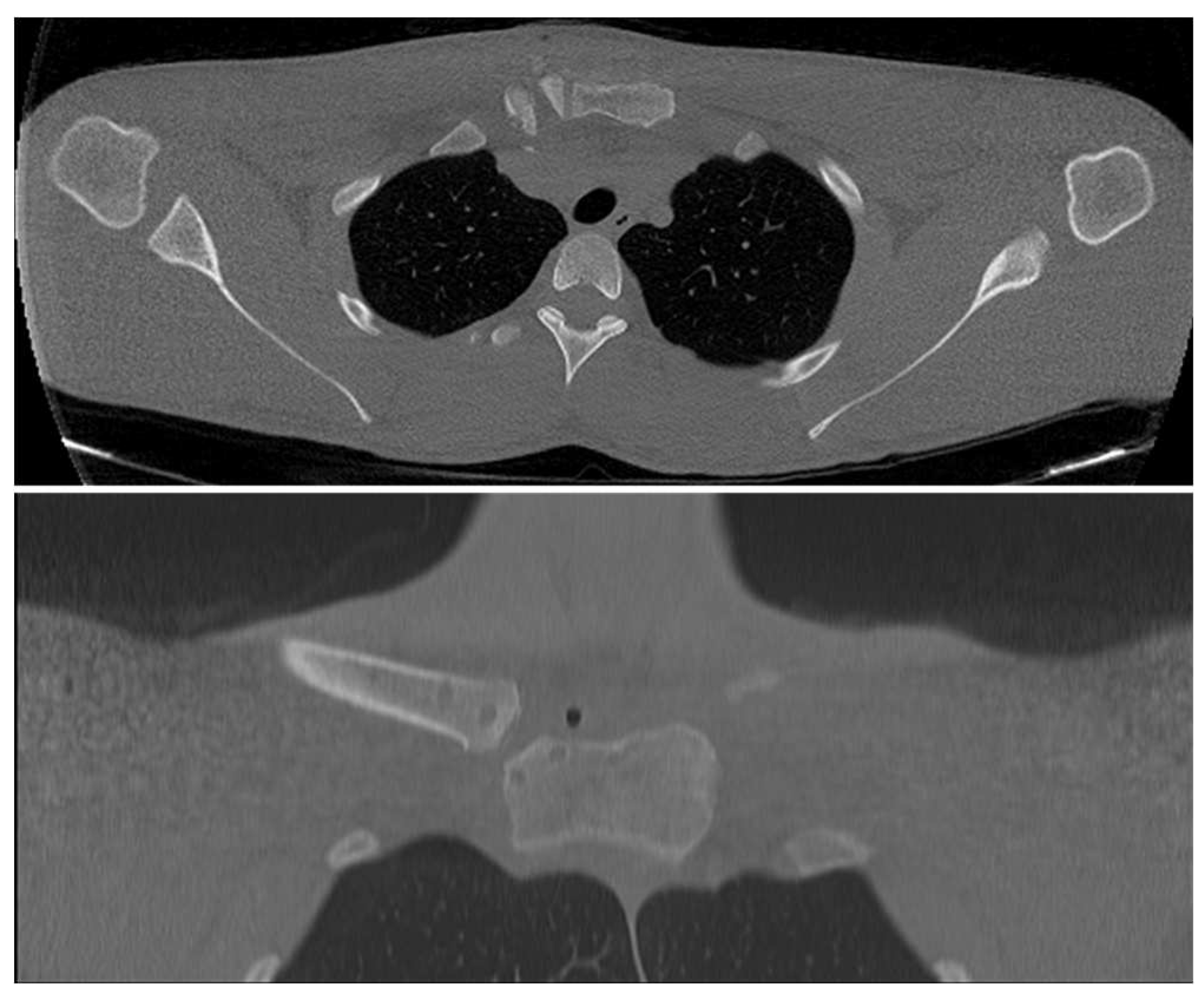

During the whole of 2021, only 2 patients came to our attention after a fall from height. Both of them reported a blow on the postero-lateral side of the shoulder, without loss of consciousness. A full body CT scan was requested for both cases and the medical report was negative for active bleeding, pneumothorax or evidence of internal organs damage; there were instead highlighted fractures and infractions of the ribs, lung parenchymal contusions, apical slight subpleural hematomas and a complete posterior dislocation of the left SCJ (

Figure 1). Either way, we tried a closed reduction of the SCJ, which proved fruitless.

The arterial blood gas analysis was checked, highlighting a respiratory insufficiency in both cases (descent of pO2 and sO2; increase of pCO2), subsequently oxygen therapy was immediately administered. After the exclusion of Sars-Cov-2 infection through nasopharyngeal swab and in accordance with all Covid-19 protocols [

19,

20,

21], the patients were finally admitted to our ward and surgery was scheduled.

A second closed reduction was tried in the operating room, hoping that the anesthesia could simplify this procedure, without any success. Consequently, we had to resort to the open reduction option.

The medical team was formed by orthopedic surgeons, a thoracic surgeon and an anaesthetist. First surgical step was the harvest of the tendon graft. We chose the semitendinosus muscle for both operations. The patients were positioned supine with the tourniquet to the thigh, and 2g of Cefazoline were administered preoperatively. For both surgeries, after setting up the sterile field and through longitudinal incision, we harvested the tendon, prepared it for transplant and then stored it in a compound made of 500ml of saline solution 0.9% + 1g of Vancomycin (

Figure 2). The first surgical stage ended with tourniquet removal, an adequate hemostasis, surgical site washing, drain-positioning, suturing and dressing.

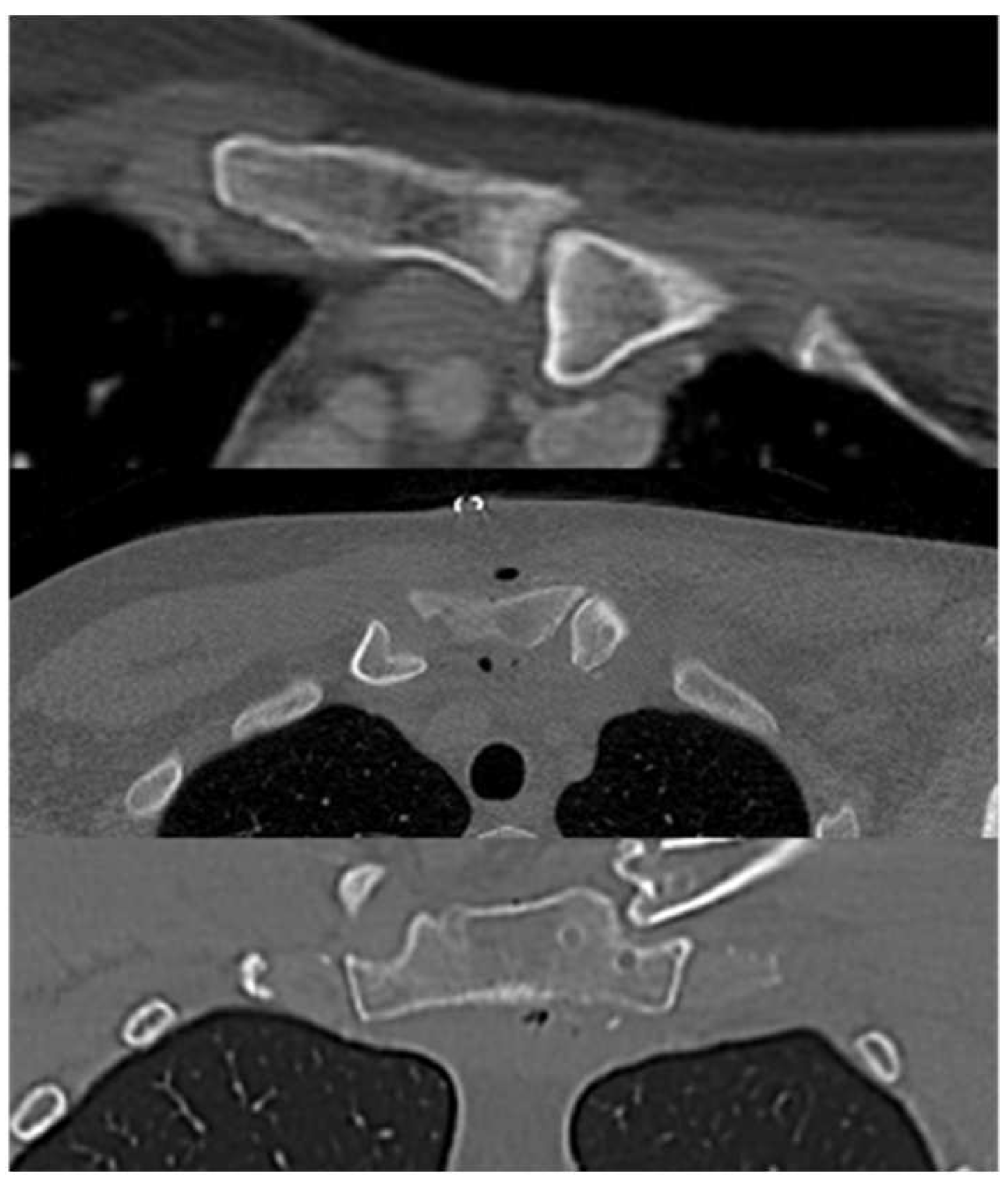

Second stage was an open reduction of the SCJ and subsequent stabilization with the autologous semitendinosus tendon graft (

Figure 3). In the same supine position and in a sterile field, we proceeded to exposing the SCJ, the sternal manubrium and the medial clavicle through an antero-superior straight incision extended from the middle part of the clavicle to the mid superior aspect of sternal manubrium, finding a posterior dislocation of the SCJ. After releasing the medial part of the clavicle and the articular facet of the sternum, four bone tunnels (diameter 5 mm) were arranged, two in the clavicle and two in the sternum, adequately protecting the noble structures underlying. After the reduction of the clavicle, we stabilized the joint with a figure-of-eight semitendinosus tendon graft reconstruction and then reinforced it with high strength suture tape (

Figure 4). A suction drainage was also positioned after appropriate hemostasis and wash. As per post operative protocol an arm sling was recommended. Elbow, wrist and hand mobilization were allowed from day 1; at 3 weeks the patient started the rehabilitation of the shoulder. At 2 months, a new CT scan was performed and it showed a complete reduction, both on the axial and the coronal view (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6).

Both patients were followed up for 1 year postoperative, with clinical evaluation and radiograps: the ROM was restored, with an optimal strength recovery and no neurological deficits; in both cases the healing of the fracture was successfully obtained; our patients returned to their normal life.

Figure 7.

Clinical evaluation, 1 year follow-up.

Figure 7.

Clinical evaluation, 1 year follow-up.

5. Discussion

Compared to other pathologies involving the shoulder girdle, SC joint dislocation represents an infrequent pathology [

1]. It may occur due to a high kinetic energy impacts or to an a-traumatic event; this type of dislocations could happen in the absence of trauma and are therefore divided into traumatic and atraumatic groups. Atraumatic dislocations, as well as subluxation, can occur in the absence of any trauma, but many of these patients had generalized ligamentous laxity or they suffer from other pathologies, causing an alteration of normal function of the joint [

11]. SCJ dislocation usually occurs in young adults, during forward flexion and abduction of the arm; a snap is well audible and the patient reports a sensation of clicking. A recent study of Moreels et al. focused on the treatment of atraumatic SC dislocations: they support that the ‘‘wait-and- see’’ policy is the best solution in these cases, as it has been shown in their study. In fact, pathology has a self-limiting tendency in most cases and the authors registered a reduction of re-dislocations and complaints; on the other hand, during the follow-up period some patients continued to experience dislocations [

22].

Furthermore, if the dislocation is traumatic, the involved clavicle may move anteriorly or posteriorly to the sternum, but statistically the anterior dislocation is about 9 times more frequent [

23]. The treatment of this condition is usually a closed reduction but there is a recurrence rate ranging from 21 and 100%, consequently the debate between conservative and surgical treatment is still open [

11].

The main mechanisms for traumatic posterior SC dislocations is postero-lateral compressive force acting on the shoulder with high velocity or a direct force to the clavicle on its antero-medial aspect, displacing the head of the clavicle posteriorly [

11]. In terms of athletes, most of them play football or rugby and often undergo direct blows or falls on outstretched hands [

24].

The scientific literature about this topic is extremely poor and often controversial. Undoubtedly one of the main reasons is the great rarity of this pathology, and consequently the lack of real orthopaedic experts in this field. As evidence of this, there are no reviews focused on traumatic posterior SCJ dislocations.

The best treatment for the initial management of this pathology is the nonoperative management (closed reduction), but unfortunately this technique does not always succeed. We used the method described by Groh et al.: the patient is positioned supine, with the affected shoulder near the edge of the table. It is useful to place a sandbag between the shoulders; with a movement of traction and abduction of the arm, the clavicle is dis-impacted from the sternum and then the shoulder is gradually brought back into extension to reduce the SCJ. It is good to highlight that the traction must always precede the extension, otherwise the medial clavicle would bind the manubrium [

23]. After this manouvre it is useful to confirm the reduction through a CT scan [

9]. If the dislocation is treated in the operating room, the reduction and stability of the joint should be evaluated with fluoroscopy, in addition to the clinical examination. Previous studies reported persisting instability of the SC joint after nonoperative closed reduction. This especially occurs when the dislocation involves paediatric patients, who have an immature bone skeleton in which physis are still open and can be dislocate posteriorly or be fractured. In case of failure of a closed reduction, this leads to a delay in the definitive treatment of SC joint dislocations, and commonly needs a deferred open reduction and stabilization. Thankfully, in a systematic review conducted by Glass et al, Authors stated that surgical reduction is feasible even when closed reduction fails and the effectiveness of the procedure is not adversely affected by the failure of conservative treatment [

25].

When nonoperative treatment is not possible or not efficient (persistent joint instability), open reduction is needed and surgeons have to stabilize the joint in order to avoid any possible compression on the structures of the thoracic cavity. Unfortunately, the choice of the correct surgical treatment is not simple, since there are no clear guidelines to follow and the literature reports many possible options. It is still hard to compare any results because they are characterized by small numbers, different options of treatment (i.e. closed reduction or open reduction; internal fixation with plate and screws, cannulated screws, transosseous suture, reconstruction with hamstring tendons or LARS, figure-of-eight suture with PDS

Tm Cord, tension band wiring with K-wires), short follow up and none of them differentiates acute from chronic SC dislocation; therefore it is not possible to state that one surgical technique is better than others. On the other side, all papers reported good and satisfactory outcomes in case of traumatic SCJ dislocation [

2,

5,

6,

11,

12,

13,

18,

26,

27]. One of the latest reviews suggests that if closed reduction fails, the best solution is an open reduction associated with an internal fixation and all methods of fixation are equiparable [

6]. As a result, the surgeon is left wide discretion based on his experience.

This last point leaves us perplexed, because as there are surgeons who aim to preserve the mobility of the joint while others choose to immobilize it. The fact that different surgical treatments have the same results seems simplistic and unrealistic. If so, despite any possible limitations, the restoration of physiological SCJ’s range of motion would not matter, therefore even an arthrodesis of this joint (created using a plate fixed with proper screws) can lead to successful outcomes.

Previous studies underlined that treatment with plate and screws may cause damage and severe complications, as well as not being a viable solution in children [

28]. Surely the resulting fixation would be firm and stable, but the ROM of the joint would be severely limited and a stress concentration may occur during functional exercises.

Despite the normal ROM of the SCJ is narrow, we think that it needs to be re-established. Otherwise, the surgical immobilization of the joint induces the patient to compensate any movement by using the more downstream ones [

13]. The creation of an arthrodesis at this level partially compromises the normal activities of daily life, especially in young patients, so we prefer to avoid rigid fixation systems. When posterior SC dislocation is surgically treated, anatomical ligaments’ reconstruction is an option to consider carefully, because it can affect the stability of the joint. The presented technique allows the reconstruction of the anterior and posterior sterno-clavicular ligaments, as well as the posterior capsule, ensuring stability and movement to the joint [

2]. In addition, previous studies have demonstrated that the figure of eight method granted a high posterior stability to the SCJ [

29].

Tytherleigh-Strong et al. evaluated a series of 19 patients with acute traumatic posterior SCJ dislocation treated with hamstring tendon autograft reconstruction technique within 14 days from injury [

30]. After a minimum follow up of 3 years, they reported a high survivorship grade (96%), good clinical outcomes, and a high rate of return to sports (86% of patients who practiced sports were able to return to their pre-injury level).

The use of autologous tendons adds the risk of morbidity at the harvest site, on the contrary it cancels both the one of intolerance to osteosynthesis devices and the graft rejection [

2].

The costoclavicular ligament has to be correctly repositioned as it is very important for joint stability, so it has to be repaired when damaged [

18]. An additional stabilization can be done with a fixation of the medial end of the clavicle to the sternum through a suture tape or a tendon transfer, using hamstring or palmaris longus tendon grafts. Given the proximity of noble structures, an adequate knowledge of the anatomy is mandatory to properly treat this event and to prevent running into potentially fatal complications, as reported in literature [

26]. Indeed, in case of surgery it is advisable to pre-alert a thoracic and/or a cardiovascular surgeon. This procedure should not be done with K-wire or pins, as there is a real risk of displacement of these devices which may even be fatal for the patient [

10,

31]. In particular, a risk of death up to 40% has been estimated when using K wires due to the potential vascular complications [

7].

The most striking case in this regard was reported by Ballas et al. concerning a patient with posterior dislocation of the sternoclavicular joint, who was treated with 3 K wires: the first was removed after a short time since it was protruding below the skin; the second after 2 years protruded vertically in front of the sternum, giving symptoms similar to myocardial infarction; the last one migrated into the pelvic cavity, giving abdominal symptoms and multiple surgical interventions were necessary to be able to extract it [

32]. In the same paper, the Authors also carried out a literature review, reporting 78 articles and 88 cases of K-wire migration, of which 18 following sternoclavicular joint dislocation.

Another similar surgical way to stabilize the SCJ in young and active patients can be the use of artificial ligament or with special sutures. The employment of LARS (Ligament Augmentation and Reconstruction System) technique has been demonstrated to be a feasible option, able to address both costo-clavicular and capsular ligaments. Quayle et al. reported 5 cases of SCJ dislocations treated with LARS and interference screws, with promising short and mid-term outcomes, such as lowering of pain and improvement of joint function [

33]. Alternatively, Castellani et al. performed a figure-of-eight suture using the PDS

Tm Cord (Ethicon Johnson & Johnson International), joined with an additional suture between the sternum and the clavicle in order to repair the capsule and increases the stability of the joint [

34].

It is important to distinguish SC dislocations according to the timing: if dislocation is not treated within 48 hours, it has to be considered as a delayed presentation; on the other hand, a chronic dislocation is to be considered when scar tissue has already formed and the symptoms have stabilized. Acute presentation could not have a complete rupture of ligaments and it may be possible to repair it consequently. Closed reduction is more effective in the first 48 hours after trauma. Timing of surgery is also very important when surgery is necessary because it has been verified that the functional outcomes are better in acute dislocations, so it must be performed before the disease becomes chronic [

17,

26]. Furthermore, peculiar complications may occur in non surgically treated posterior SC chronic dislocation [

9,

26].

When the posterior dislocation affects young patients this can be potentially dangerous, as well as frequently neglected [

8]. In these cases clinical and radiographic findings may not be diagnostic and they must be supplemented by CT scan or MRI, which can also evaluate possible mediastinal complications [

7]. A conservative treatment with closed reduction under general anaesthesia can be effective in young patients, thanks to their remodelling capability, even if close follow-up may be necessary [

8].

The study has an important limitation, that is the few numbers of patients. As already mentioned, all surgeons have limited numbers on this pathology and it is very difficult to study it with statistical significance, if not impossible. Consequently, further studies and subsequent patients will be necessary to verify the effectiveness of this surgical technique.