Submitted:

27 December 2023

Posted:

03 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

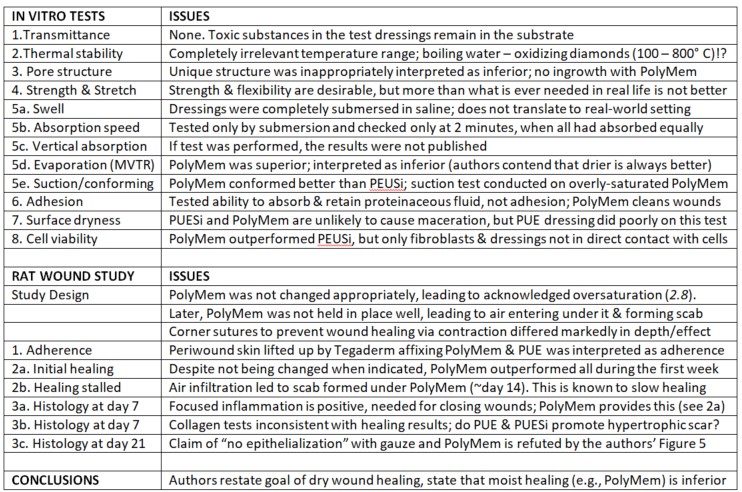

2. Specific Issues

2.1. How the in vitro test results translate to real-world clinical settings

- PolyMem and the two study dressings performed similarly on the transmittance (spectroscopy) test, which is interesting, but relevant only because the new dressings contain triethoxysilane (APTES). APTES is potentially fatal if inhaled, and even mild skin exposures can lead to systemic effects.[24] In contrast, PolyMem’s components are gentle on skin and completely nontoxic.[3,6,25,26]

- Thermal stability was tested at temperatures ranging from 100° C (the boiling point of water) to 800° C, which is hot enough to oxidize diamonds. PolyMem is designed for use on humans and animals, who cannot withstand such temperature extremes. PolyMem performs well when stored and used in a tropical environment.[22,27,28]

- The authors noted that PolyMem has a very unique pore structure, as if this were an inherent problem. Independent researchers have found that this unique pore structure allows PolyMem to absorb fluids almost instantly while completely avoiding ingrowth of tissue into the dressing, features not tested in this study.[12,21,29,30]

- Both test dressings outperformed PolyMem on strength and stretch tests. Although it is true that an ideal dressing should possess excellent flexibility and mechanical strength, it is not true that the best dressing is the one that is the strongest and the most flexible. Other criteria are important as well. PolyMem is renowned for how comfortable and conformable it is.[3,5,31] Its flexibility and strength are more than adequate for real-world applications.[12,26,29,32,33]

- Although the authors used Simulated Body Fluid for the swelling test, inexplicably, absorption was tested with buffered saline.[1] To prevent maceration, dressings should absorb fluid both vertically and quickly.[14] No test results of these aspects of absorption were reported. Absorption was tested by completely immersing the dressings, which would not happen in real-life settings. PolyMem and both of the test dressings absorbed large quantities of saline and were fully saturated at 2 minutes, which was the first time interval assessed.[1] The authors speculated about reasons for PolyMem’s excellent absorption performance, again indicating a lack of knowledge of the complex moisture-balancing system PolyMem provides wound patients.[30,33,34,35]

- 6.

- The “anti-adhesion test” in this study did not assess for adherence to the wound bed directly, but rather, the ability of the dressing to absorb and retain proteinaceous fluid was used as a surrogate.[1] Equating absorption of cellular debris with adherence has already been repudiated.[42] This test is invalid for testing adhesion because PolyMem is designed to break the chemical bonds between the slough and other wound contaminants in the wound bed and pull these contaminants up into the dressing, and many of these substances contain protein.[26,33,42,43,44,45] PolyMem dramatically outperformed the PUE and PUESi dressings in its ability to absorb proteinaceous fluid (like debris-containing chronic wound fluid).[1] PolyMem’s ability to continuously atraumatically cleanse and debride wounds is a beneficial feature, and is completely unrelated to adherence to the wound bed.[42] Independent clinicians and researchers consistently find that PolyMem does not adhere to the wound bed.[2,12,19,20,25,29,31,33,39,40,41,44,46,47,48]

- 7.

- 8.

- PolyMem outperformed the PUESi dressing (as well as gauze) on the “cell viability” at 24 hours test, but this does not appear to be a meaningful test.[1] Keratinocytes and, importantly, white blood cells, were excluded from the test, which was conducted by “treating” fibroblasts with fluid extracted from dressings soaked for an unstated period of time with an unstated fluid. Why were the dressings not placed in direct contact with any living cells?

2.2. How the test results in rats translate to real-world clinical settings

- In contrast to the gauze dressing, the PolyMem pad did not adhere to the wound beds at all.[1] However, because the Tegaderm affixing the dressings was inconsistently loosened from the skin prior to the photos being taken, the periwound skin was lifted up by the Tegaderm in the photos of PolyMem on the Non-DM rat (upper left), PolyMem on the DM rat (lower right), and PUE on the DM rat (lower right). See Figure 4.[1]

- Despite PolyMem not being changed at appropriate intervals, during the first week it outperformed all three other dressings in the non-DM model and matched the performance of the PUESi and PUE dressings in the DM model, with clear signs of granulation and measurable brisk healing.[1] However, around day 14, healing under the PolyMem dressings slowed. The authors note (2.11) that the wounds covered with PolyMem developed “eschar” in the wound bed.[1] Eschar (or more likely, scab) is an indication that the wound bed became dry. It seems likely that the PolyMem dressings were not securely affixed to the wound bed at that time. This would explain why the healing under PolyMem, which had been the most rapid of all the groups, suddenly stalled.

- 3.

- The histological analyses reported here raise many questions. The biopsies were taken on day 7, at which time, according to Figure 5, the wounds managed with PolyMem had improved more than all the other wounds in the non-DM rats and more than all except the PUE-managed DM rat.[1] Why are the collagen test results in Figure 7 so dramatically inconsistent with these results and the images in Figure 5, especially when compared with the gauze-managed DM rat?[1] Could it be that PolyMem is the only study dressing that is not promoting excess collagen formation (which leads to hypertrophic scarring)? Or is the test simply inaccurate? Would conducting biopsies during the middle of the healing process (on day 7 of 21) affect the results of the healing study? Did the unblinded investigators conduct the biopsies without bias?

3. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, C.-F.; Chen, S.-H.; Chen, R.-F.; Liu, K.-F.; Kuo, Y.-R.; Wang, C.-K.; Lee, T.-M.; Wang, Y.-H. A Multifunctional Polyethylene Glycol/Triethoxysilane-Modified Polyurethane Foam Dressing with High Absorbency and Antiadhesion Properties Promotes Diabetic Wound Healing. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 12506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, H.K.R.; Chong, S.S.; Hasbullah, M. A Unique, Multifunctional Dressing in Chronic Wound Management. Wounds Asia 2021, 4, 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Dechant, E.D. Considerations for Skin and Wound Care in Pediatric Patients. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 2022, 33, 759–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haze, A.; Gavish, L.; Elishoov, O.; Shorka, D.; Tsohar, T.; Gellman, Y.N.; Liebergall, M. Treatment of Diabetic Foot Ulcers in a Frail Population with Severe Co-Morbidities Using at-Home Photobiomodulation Laser Therapy: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Sham-Controlled Pilot Clinical Study. Lasers Med Sci 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafter, L.; Rafter, M. Achieving Effective Patient Outcomes with PolyMem® Silicone Border. Br J Community Nurs 2021, 26, 498–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hess, C.T. Product Guide to Skin & Wound Care, 8th edition; Woltors Kluwer: Philadelphia, PA USA, 2020; ISBN 978-1-4963-8809-4. [Google Scholar]

- Cutting, K.F.; Gefen, A. PolyMem and Countering Inflammation. Wounds International 2019, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, S. m.; Walker, M.; Rogers, A. a.; Chen, W. y. j. Importance of Moisture Balance at the Wound-Dressing Interface. J Wound Care 2003, 12, 125–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutchinson, J.J.; McGuckin, M. Occlusive Dressings: A Microbiologic and Clinical Review. Am J Infect Control 1990, 18, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, M.L. Exudate: Friend or Foe? Br J Community Nurs 2014, 19, S18–S23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, L.L. Common Nonsense: Rediscovering Moist Wound Healing | Wound Management & Prevention. Wound Management & Prevention Journal 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Benskin, L.L. Evidence for Polymeric Membrane Dressings as a Unique Dressing Subcategory, Using Pressure Ulcers as an Example. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle) 2018, 7, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, B. The Diabetic Foot: A Comprehensive Approach. In The wound management manual; McGraw-Hill: New York, 2005; pp. 360–361. [Google Scholar]

- Dabiri, G.; Damstetter, E.; Phillips, T. Choosing a Wound Dressing Based on Common Wound Characteristics. Advances in Wound Care 2014, 5, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulder, M. The Selection of Wound Care Products for Wound Bed Preparation. Wound Healing Southern Africa 2009, 2, 76–78. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, S. Surgical Dressings and Wound Management, 2nd ed.; Kestrel Health Information: Hinesburg VT, 2012; ISBN 978-0-9728414-0-5. [Google Scholar]

- Maniya, S.D.; Aw, D.; Chen, Wee; Chowdhury, A.R. Pressure Injury. In The Geriatric Admission A Handbook for Hospitalists; WORLD SCIENTIFIC, 2023; pp. 299–309. ISBN 9789811270697. [Google Scholar]

- Jeevan, J.; Saleh, W.S.W.; Ghani, N.A. Managing Chronic, Autoimmune Disease-Related Wounds with a Polymeric Membrane Dressing - Wounds Asia. Wounds Asia 2019, 2, 34–37. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.J.; Lee, S.W.; Hong, S.H.; Lee, H.K.; Kim, E.K. The Effects of PolyMem(R) on the Wound Healing. Journal of the Korean Society of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgeons 1999, 26, 1165–1172. [Google Scholar]

- Sibbald, R.G.; Persaud Jaimangal, R.; Coutts, P.M.; Elliott, J.A. Evaluating a Surfactant-Containing Polymeric Membrane Foam Wound Dressing with Glycerin in Patients with Chronic Pilonidal Sinus Disease. Adv Skin Wound Care 2018, 31, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skrinjar, E.; Duschek, N.; Bayer, G.S.; Assadian, O.; Koulas, S.; Hirsch, K.; Basic, J.; Assadian, A. Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing the Combination of a Polymeric Membrane Dressing plus Negative Pressure Wound Therapy against Negative Pressure Wound Therapy Alone: The WICVAC Study. Wound Rep and Reg 2016, n/a–n/a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benskin, L.L. Polymeric Membrane Dressings for Topical Wound Management of Patients With Infected Wounds in a Challenging Environment: A Protocol With 3 Case Examples. Ostomy Wound Manage 2016, 62, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahn, A.; Kleinman, Y. A Novel Approach to the Treatment of Diabetic Foot Abscesses - a Case Series. J Wound Care 2014, 23, 394, 396–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Biotechnology Information Triethoxysilane. Available online:. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/6327710 (accessed on 5 October 2023).

- Fowler, E.; Papen, J.C. Clinical Evaluation of a Polymeric Membrane Dressing in the Treatment of Dermal Ulcers. Ostomy Wound Manage 1991, 35, 35–38, 40–44. [Google Scholar]

- Denyer, J.E.; Pillay, E.; Clapham, J. Best Practice Guidelines for Skin and Wound Care in Epidermolysis Bullosa. An International Consensus 2017.

- Benskin, L. A Test of the Safety, Effectiveness, and Acceptability of an Improvised Dressing for Sickle Cell Leg Ulcers in a Tropical Climate; clinicaltrials.gov, 2021.

- Nair, H.K.R. Pyoderma Gangrenosum. In Uncommon Ulcers of the Extremities; Khanna, A.K., Tiwary, S.K., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 225–230. ISBN 978-981-9917-82-2. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, P.P. Postoperative Endonasal Dressing with Polymeric Membrane Material. Presented at the American Rhinologic Society 49th Fall Scientific Meeting, Orlando, FL, 2003.

- Yastrub, D.J. Relationship between Type of Treatment and Degree of Wound Healing among Institutionalized Geriatric Patients with Stage II Pressure Ulcers. Care Manag J 2004, 5, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafter, L.; Oforka, E. Standard versus Polymeric Membrane Finger Dressing and Outcomes Following Pain Diaries. Wounds UK 2014, 10, 40–49. [Google Scholar]

- Lonie, G. Polymeric Membrane Tube Site Dressings Improve Tracheostomy Site Management While Increasing Patient Comfort. Presented at the Australian Wound Management Association, Perth, Australia, 2010.

- Weissman, O.; Hundeshagen, G.; Harats, M.; Farber, N.; Millet, E.; Winkler, E.; Zilinsky, I.; Haik, J. Custom-Fit Polymeric Membrane Dressing Masks in the Treatment of Second Degree Facial Burns. Burns 2013, 39, 1316–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benskin, L.L. Commentary: First-Line Interactive Wound Dressing Update: A Comprehensive Review of the Evidence. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denyer, J.; White, R.; Ousey, K.; Agathangelou, C.; HariKrishna, R. PolyMem Dressings Made Easy. Wounds International 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bolton, L. Operational Definition of Moist Wound Healing. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2007, 34, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obagi, Z.; Damiani, G.; Grada, A.; Falanga, V. Principles of Wound Dressings: A Review. Surg Technol Int 2019, 35. [Google Scholar]

- Grey, J.E.; Harding, K.G.; Enoch, S. Venous and Arterial Leg Ulcers. BMJ 2006, 332, 347–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A. Polymeric Membrane Dressings for Radiotherapy-Induced Skin Damage. Br J Nurs 2014, 23, S24, S26-31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegarty, F.; Wong, M. Polymeric Membrane Dressing for Radiotherapy-Induced Skin Reactions. Br J Nurs 2014, 23 Suppl 20, S38-46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, D.; Aleksinko, P. Use of Polymeric Membrane Dressings Immediately After Fractionated Facial Laser Resurfacing Procedures Improves Outcomes. Presented at the Symposium on Advanced Wound Care(SAWC) SPRING, Orlando, FL USA, 2010.

- Benskin, L.L. Methods Used in the Study, Evaluation of a Polyurethane Foam Dressing Impregnated with 3% Povidone-Iodine (Betafoam) in a Rat Wound Model, Led to Unreliable Results. Ann Surg Treat Res 2018, 95, 230–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agathangelou, C. Treating Fungating Breast Cancer Wounds with Polymeric Membrane Dressings, an Innovation in Fungating Wound Management. Presented at the SAWC (Symposium on Advanced Wound Care), Atlanta, GA USA, 2016.

- Carr, R.D.; Lalagos, D.E. Clinical Evaluation of a Polymeric Membrane Dressing in the Treatment of Pressure Ulcers. Decubitus 1990, 3, 38–42. [Google Scholar]

- Vanwalleghem, G. A New Protocol for the Treatment of Pilonidal Cysts. Presented at the European Wound Management Asssociation (EWMA), Brussels Belgium, 2011.

- Rafter, L.; Oforka, E. Trauma-Free Fingertip Dressing Changes. Wounds UK 2013, 9, 96–100. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, J.; Mason, S. An Evaluation of the Use of PolyMem Silver in Burn Management. Journal of Community Nursing 2010, 24, 16–19. [Google Scholar]

- Campton-Johnston, S.; Wilson, J.; Ramundo, J.M. Treatment of Painful Lower Extremity Ulcers in a Patient with Sickle Cell Disease. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 1999, 26, 98–104. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Z.; Huang, Y.; Luo, G.; Wu, J.; He, W. A Biological Membrane-Based Novel Excisional Wound-Splinting Model in Mice (With Video). Burn Trauma 2014, 2, 196–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anstead, G.M. Steroids, Retinoids, and Wound Healing. Adv Wound Care 1998, 11, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Laird, J.R.; Cavros, N.; Gallino, R.; McCormick, D.; Elliott, K.W.; Holton, M. Foreign Body Contamination During Interventional Procedures. Endovascular Today 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Blackman, J.D.; Senseng, D.; Quinn, L.; Mazzone, T. Clinical Evaluation of a Semipermeable Polymeric Membrane Dressing for the Treatment of Chronic Diabetic Foot Ulcers. Diabetes Care 1994, 17, 322–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas Hess, C. Checklist for Factors Affecting Wound Healing. Advances in Skin & Wound Care 2011, 24, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, T.; Ousey, K.; Haesler, E.; Bjarnsholt, T.; Carville, K.; Idensohn, P.; Kalan, L.; Keast, D.H.; Larsen, D.; Percival, S.; et al. IWII Wound Infection in Clinical Practice Consensus Document: 2022 Update. J Wound Care 2022, 31, S10–S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).