Submitted:

30 December 2023

Posted:

03 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Data and Sample

2.2. Measures

2.3. Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest Statement

References

- Hossain B, Yadav PK, Nagargoje VP, Vinod Joseph KJ. Association between physical limitations and depressive symptoms among Indian elderly: marital status as a moderator. BMC Psychiatry. 2021, 21, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali S, Stone MA, Peters JL, Davies MJ, Khunti K. The prevalence of co-morbid depression in adults with Type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabet Med. 2006, 23, 1165–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matcham F, Rayner L, Steer S, Hotopf M. The prevalence of depression in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2013, 52, 2136–2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palinkas LA, Wingard DL, Barrett-Connor E. The biocultural context of social networks and depression among the elderly. Soc. Sci. Med. 1990, 30, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkman LF, Berkman CS, Kasl S, et al. Depressive symptoms in relation to physical health and functioning in the elderly. Am J Epidemiol. 1986, 124, 372–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitz N, Wang J, Malla A, Lesage A. Joint effect of depression and chronic conditions on disability: results from a population-based study. Psychosom Med. 2007, 69, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penninx BW, Beekman AT, Ormel J, et al. Psychological status among elderly people with chronic diseases: does type of disease play a part? J Psychosom Res. 1996, 40, 521–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bazargan M, Hamm-Baugh VP. The relationship between chronic illness and depression in a community of urban black elderly persons. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1995, 50, S119–S127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black SA, Goodwin JS, Markides KS. The association between chronic diseases and depressive symptomatology in older Mexican Americans. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1998, 53, M188–M194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong D, Solomon P, Dong X. Depressive Symptoms and Onset of Functional Disability Over 2 Years: A Prospective Cohort Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019, 67, S538–S544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budiman A, Ruiz NG. Asian Americans Are the Fastest-Growing Racial or Ethnic Group in the U.S. /: 2021. Retrieved from https, 2021; Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/04/09/asian-americans-are-the-fastest-growing-racial-or-ethnic-group-in-the-u-s/.

- Ruggles S, Flood S, Goeken R, Schouweiler M, Sobek M. IPUMS USA, /: IPUMS USA. 2022. Accessed January 23, 2023, https://usa.ipums.org/usa/.

- Alperin E, Batalova J. Vietnamese Immigrants in the United States, /: Institute (MPI); 2018. Retrieved from https, 2018; Retrieved from https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/vietnamese-immigrants-united-states-5.

- Gold S., J. Mental health and illness in Vietnamese refugees. West J Emerg Med. 1992, 157, 290–294. [Google Scholar]

- Bloch A, Hirsch S. Inter-generational transnationalism: the impact of refugee backgrounds on second generation. Comp Migr Stud. 2018, 6, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyawaki CE, Chen NW, Meyer OL, Tran MT, Markides KS. Vietnamese adult-child and spousal caregivers of older adults in Houston, Texas: Results from the Vietnamese Aging and Care Survey (VACS). J Gerontol Soc Work. 2020, 63, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyawaki CE, Liu M, Markides KS. Association between caregivers’ characteristics and older care recipients’ well-being among Vietnamese immigrant families in the United States. J Community Psychol. 2022, 50, 2214–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyawaki CE, Liu M, Park VT, Tran MT, Markides KS. Social support as a moderator of physical disability and mental health in older Vietnamese immigrants in the U.S.: Results from the Vietnamese Aging and Care Survey (VACS). Geriatr Nur (Lond). 2022, 44, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyawaki CE, Meyer OL, Chen NW, Markides KS. Health of Vietnamese older adults and caregiver’s psychological status in the United States: Result from the Vietnamese Aging and Care Survey. Clin Gerontol. 2020, 45, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyawaki CE, Garcia JM, Nguyen KN, Park VT, Markides KS. Multiple chronic conditions and disability among Vietnamese older adults: Results from the Vietnamese Aging and Care Survey (VACS) [published online ahead of print, 2023 May 30]. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Pew Research Center. Top 10 U.S. Metropolitan Areas by Vietnamese Population, 2019, Pew ResearchCenter: 2021. Accessed , 2022. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/chart/top-10-u-s-metropolitanareas- by-vietnamese-population-2019/, 19 July 2021.

- Meyer OL, Nguyen KH, Dao TN, Vu P, Arean P, Hinton L. The sociocultural context of caregiving experiences for Vietnamese dementia family caregivers. Asian Am J Psychol. 2015, 6, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorkin D, Tan AL, Hays RD, Mangione CM, Ngo-Metzger Q. Self-reported health status of Vietnamese and non-Hispanic white older adults in California. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008, 56, 1543–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller-Thomson E, Brennenstuhl S, Hurd M. Comparison of disability rates among older adults in aggregated and separate Asian American/Pacific Islander subpopulations. Am J Public Health. 2011, 101, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Markides K, Chen NW, Angel R, Palmer R, Graham J. Hispanic Established Populations for the Epidemiologic Study of the Elderly (HEPESE) Wave 7, 2010-2011 [Arizona, California, Colorado, New Mexico, and Texas]. Published online 2016. [CrossRef]

- Do M, Ha Bui BK, K. Pham N, et al. Validation of MoCA test in Vietnamese language for cognitive impairment screening. J Glob Health Neurol Psychiatry, Published online May 20, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: A Brief Screening Tool For Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005, 53, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radloff, LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977, 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thai TT, Jones MK, Harris LM, Heard RC. Screening value of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies – Depression scale among people living with HIV/AIDS in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam: A validation study. BMC Psychiatry. 2016, 16, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen HT, Le VA, Dunne M. Validity and reliability of the two scales measuring depression and anxiety used in community survey in Vietnamese adolescents. Vietnam J Public Health. 2007, 7, 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. Studies of illness in the aged: The index of ADL: A standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA. 1963, 185, 914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. The Gerontologist. 1969, 9 Pt 1, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field-Fote, EE. Mediators and moderators, confounders and covariates: Exploring the variables that illuminate or obscure the "Active Ingredients" in neurorehabilitation. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2019, 43, 83–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiñones AR, Markwardt S, Botoseneanu A. Diabetes-multimorbidity combinations and disability among middle-aged and older adults. J Gen Intern Med. 2019, 34, 944–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector WD, Fleishman JA. Combining activities of daily living with instrumental activities of daily living to measure functional disability. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1998, 53, S46–S57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mwangi J, Kulane A, Van Hoi L. Chronic diseases among the elderly in a rural Vietnam: prevalence, associated socio-demographic factors and healthcare expenditures. Int J Equity Health. 2015, 14, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho-Pham LT, Lai TQ, Mai LD, Doan MC, Pham HN, Nguyen TV. Prevalence of radiographic osteoarthritis of the knee and its relationship to self-reported pain. PLoS One. 2014, 9, e94563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen AT, Nguyen THT, Nguyen TTH, et al. Chronic pain and associated factors related to depression among older patients in Hanoi, Vietnam. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021, 18, 9192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strong C, Hur K, Kim F, Pan J, Tran S, Juon HS. Sociodemographic characteristics, knowledge and prevalence of viral hepatitis infection among Vietnamese Americans at community screenings. J Immigr Minor Health. 2015, 17, 298–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowdley KV, Wang CC, Welch S, Roberts H, Brosgart CL. Prevalence of chronic hepatitis B among foreign-born persons living in the United States by country of origin. Hepatology. 2012, 56, 422–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham C, Fong TL, Zhang J, Liu L. Striking racial/ethnic disparities in liver cancer incidence rates and temporal trends in California, 1988-2012. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018, 110, 1259–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanh HTM, Assanangkornchai S, Geater AF, Hanh VTM. Socioeconomic inequalities in alcohol use and some related consequences from a household perspective in Vietnam. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2019, 38, 274–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn J, Kim BJ. The relationships between functional limitation, depression, suicidal ideation, and coping in older Korean immigrants. J Immigr Minor Health. 2015, 17, 1643–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, SF. Functional disability and depressive symptoms: Longitudinal effects of activity restriction, perceived stress, and social support. Aging Ment Health. 2014, 18, 767–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim BJ, Liu L, Nakaoka S, Jang S, Browne C. Depression among older Japanese Americans: The impact of functional (ADL & IADL) and cognitive status. Soc Work Health Care. 2018, 57, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim BJ, Choi Y. The relationship between Activities of Daily Living (ADL), chronic diseases, and depression among older Korean immigrants. Educ Gerontol 2015, 41, 417–427. [CrossRef]

- Conn VS, Hafdahl AR, Mehr DR. Interventions to increase physical activity among healthy adults: Meta-analysis of outcomes. Am J Public Health. 2011, 101, 751–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagic D, Wuthrich VM, Rapee RM, Wolters N. Interventions to improve social connections: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2022, 57, 885–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Full Sample | Depression | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CES-D <16 (n=124) | CES-D ≥16 (n=84) |

p | |||

| Sample | |||||

| VACS 1 | 131 (63.0) | 81 (65.3) | 50 (59.5) | 0.482 | |

| VACS 2 | 77 (37.0) | 43 (34.7) | 34 (40.3) | ||

| Years of Age | 75.42±7.17 (65-97) |

75.07±7.15 (65-97) |

75.94±7.22 (65-91) |

0.393 | |

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 117 (56.2) | 65 (52.4) | 52 (61.9) | 0.226 | |

| Male | 91 (43.8) | 59 (47.6) | 32 (38.1) | ||

| Marital Status | |||||

| Married/partnered | 131 (63.0) | 89 (71.8) | 42 (50.0) | 0.002 | |

| Not married | 77 (37.0) | 35 (28.2) | 42 (50.0) | ||

| Years in the U.S. | 24.56±13.92 (1-74) |

24.54 ±14.40 (1-74) |

24.60±13.27 (1-54) |

0.977 | |

| Years of Education | 8.22±5.49 (0-20) |

8.52±5.31 (0-19) |

7.77±5.74 (0-20) |

0.338 | |

| Household Income | |||||

| < $25,000 | 188 (90.4) | 111 (89.5) | 77 (91.7) | 0.762 | |

| $25,000-$50,000 | 13 (6.2) | 9 (7.3) | 4 (4.8) | ||

| > $50,000 | 7 (3.4) | 4 (3.2) | 3 (3.6) | ||

| Living Arrangement | |||||

| Live alone | 42 (20.2) | 23 (18.5) | 19 (22.6) | 0.588 | |

| Live with other(s) | 166 (79.8) | 101 (81.5) | 65 (77.4) | ||

| Language spoken at home | |||||

| Vietnamese only | 183 (88.0) | 109 (87.9) | 74 (88.1) | 1.000 | |

| Vietnamese & other | 25 (12.0) | 15 (12.1) | 10 (11.9) | ||

| Self-Rated Health | |||||

| Good/Excellent | 42 (20.2) | 31 (25.0) | 11 (13.1) | 0.055 | |

| Fair/poor | 166 (79.8) | 93 (75.0) | 73 (86.9) | ||

| Chronic Diseases | 158 (76.0) | 88 (71.0) | 70 (83.3) | 0.041 | |

| Arthritis | 104 (50.0) | 55 (44.4) | 49 (58.3) | 0.066 | |

| Cancer | 10 (4.8) | 6 (4.8) | 4 (4.8) | 1.000 | |

| Diabetes | 85 (40.9) | 52 (41.9) | 33 (39.3) | 0.812 | |

| Heart attack | 41 (19.7) | 21 (16.9) | 20 (23.8) | 0.296 | |

| Hypertension | 154 (74.0) | 90 (72.6) | 64 (76.2) | 0.673 | |

| Liver disease | 13 (6.2) | 3 (2.4) | 10 (11.9) | 0.013 | |

| Lung disease | 10 (6.2) | 5 (4.0) | 5 (6.0) | 0.760 | |

| Stroke | 23 (11.1) | 11 (8.9) | 12 (14.3) | 0.319 | |

| # of ADL disability | 1.37±2.19 | 1.08±2.00 | 1.80±2.39 | 0.020 | |

| # of IADL disability | 4.64±3.34 | 4.12±3.42 | 5.42±3.08 | 0.006 | |

| # of ADL and IADL disability | 6.01±4.93 | 5.60±4.97 | 6.71±4.81 | 0.116 | |

| Full Sample | VACS 1 (n=131) |

VACS 2 (n=77) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years of Age | 75.42±7.17 (65-97) |

75.50±6.38 (65-90) |

75.30±8.40 (65-97) |

0.848 |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 117 (56.2) | 71 (54.2) | 46 (59.7) | 0.527 |

| Male | 91 (43.8) | 60 (45.8) | 31 (40.3) | |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Married/partnered | 131 (63.0) | 76 (58.0) | 55 (71.4) | 0.074 |

| Not married | 77 (37.0) | 55 (42.0) | 22 (28.6) | |

| Years in the U.S. | 24.56±13.92 (1-74) |

26.70±12.99 (1-68) |

21.04±14.76 (1-74) |

0.005 |

| Years of Education | 8.22±5.49 (0-20) |

7.96±5.63 (0-20) |

8.65±5.24 (0-18) |

0.385 |

| Household Income | ||||

| < $25,000 | 188 (90.4) | 123 (93.9) | 65 (84.4) | 0.060 |

| $25,000-$50,000 | 13 (6.2) | 6 (4.6) | 7 (9.1) | |

| > $50,000 | 7 (3.4) | 2 (1.5) | 5 (6.5) | |

| Living Arrangement | ||||

| Live alone | 42 (20.2) | 32 (24.4) | 10 (13.0) | 0.071 |

| Live with other(s) | 166 (79.8) | 99 (75.6) | 67 (87.0) | |

| Language spoken at home | ||||

| Vietnamese only | 183 (88.0) | 116 (88.5) | 67 (87.0) | 0.914 |

| Vietnamese & other | 25 (12.0) | 15 (11.5) | 10 (13.0) | |

| Self-Rated Health | ||||

| Good/Excellent | 42 (20.2) | 32 (24.4) | 10 (13.0) | 0.071 |

| Fair/poor | 166 (79.8) | 99 (75.6) | 67 (87.0) | |

| Chronic Diseases | 158 (76.0) | 96 (73.3) | 62 (80.5) | 0.410 |

| Arthritis | 104 (50.0) | 63 (48.1) | 41 (53.2) | 0.566 |

| Cancer | 10 (4.8) | 6 (4.6) | 4 (5.2) | 1.000 |

| Diabetes | 85 (40.9) | 53 (40.5) | 32 (41.6) | 0.992 |

| Heart attack | 41 (19.7) | 25 (19.1) | 16 (20.8) | 0.907 |

| Hypertension | 154 (74.0) | 98 (74.8) | 56 (72.7) | 0.867 |

| Liver disease | 13 (6.2) | 9 (6.9) | 4 (5.2) | 0.853 |

| Lung disease | 10 (6.2) | 4 (3.1) | 6 (7.8) | 0.227 |

| Stroke | 23 (11.1) | 11 (8.4) | 12 (15.6) | 0.172 |

| # of ADL disability | 1.37±2.19 | 1.32±2.17 | 1.45±2.24 | 0.672 |

| # of IADL disability | 4.64±3.34 | 4.28±3.34 | 5.26±3.27 | 0.041 |

| # of ADL and IADL disability | 6.01±4.93 | 5.60±4.97 | 6.71±4.81 | 0.116 |

| Predictors | Model 1: Demographics |

Model 2: Chronic Disease |

Model 3: Functional Disability |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 11.29 [9.11, 13.47]*** | 9.68 [7.30, 12.05]*** | 8.00 [5.38, 10.62]*** |

| Gender [Female] | 2.06 [-0.86, 4.97] | 1.90 [-1.02, 4.82] | 1.93 [-0.94, 4.81] |

| Marital Status [Not Married] | 4.05 [1.05, 7.04]** | 3.70 [0.77, 6.64]* | 2.77 [-0.19, 5.73]+ |

| Arthritis | 2.69 [-0.11, 5.48]+ | 1.80 [-1.03, 4.62] | |

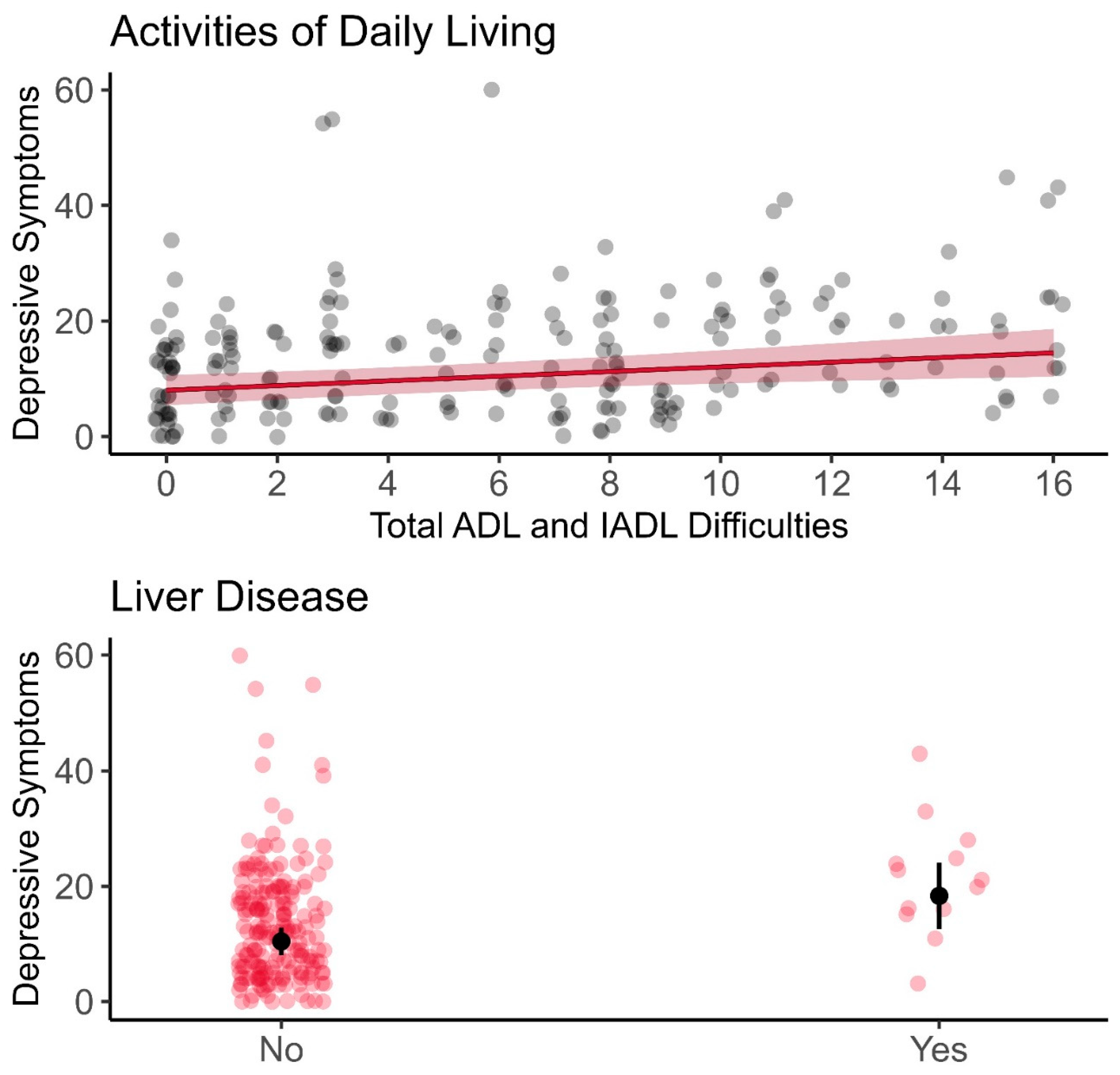

| Liver Disease | 7.69 [2.05, 13.33]** | 7.90 [2.35, 13.45]** | |

| ADL & IADL Disability | 0.40 [0.12, 0.69]** | ||

| R2 | 0.057 | 0.110 | 0.143 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.047 | 0.093 | 0.122 |

| AIC | 1557.7 | 1549.5 | 1543.7 |

| Residual df | 205 | 203 | 202 |

| Residual Sum of Squares | 20956.09 | 19764.33 | 19033.38 |

| Model Comparison F | - | 6.324 | 7.757 |

| Model Comparison p | - | 0.002 | 0.006 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).