Submitted:

02 January 2024

Posted:

04 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Bioactivity of imine-iron complexes

2.1. Imine-iron complexes as anticancer agents

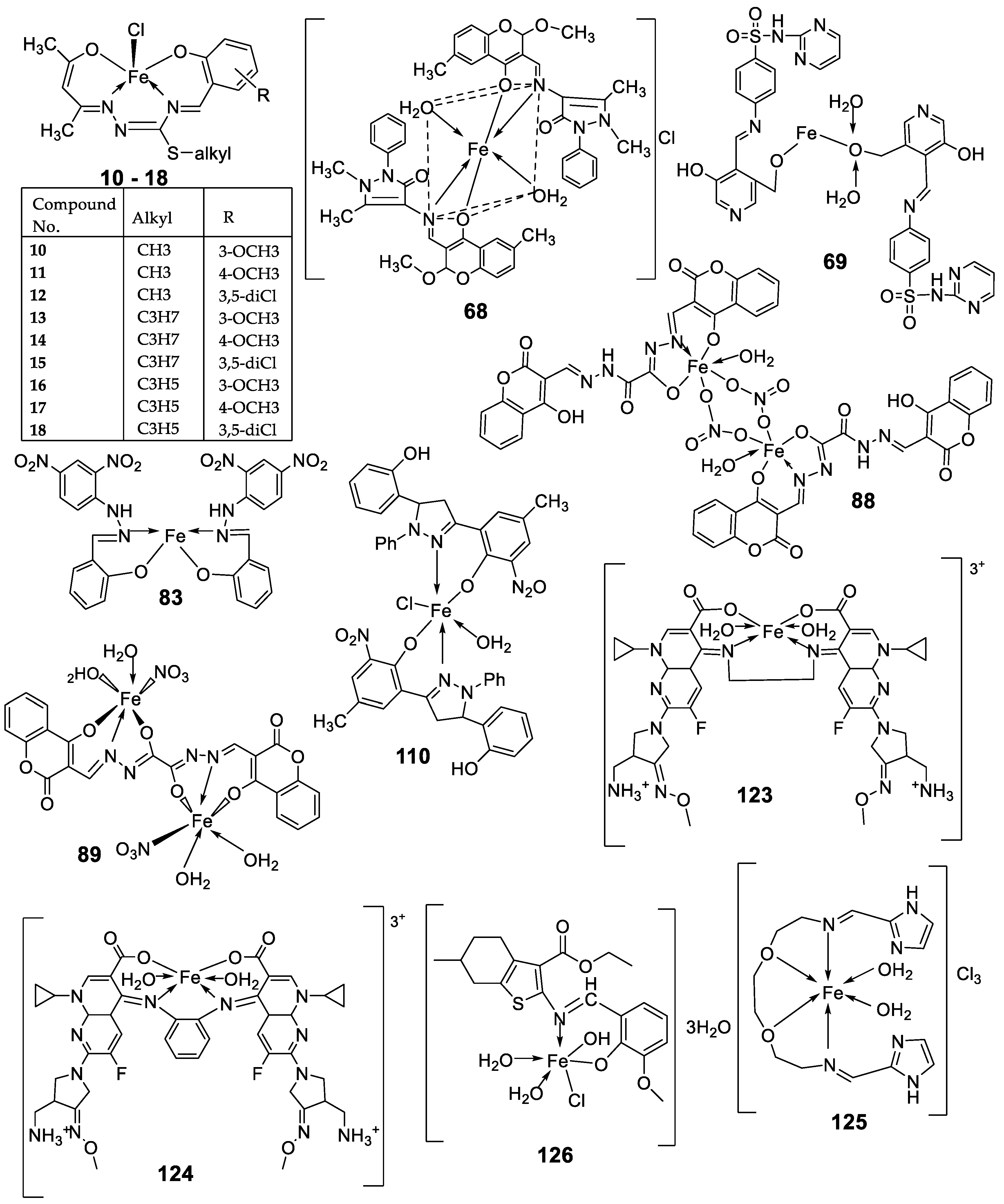

| Entry No. | Complex No. | Structures | Synthesis condition | Complex & Positive control |

Cancer cell lines |

Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

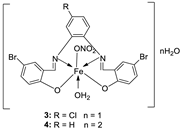

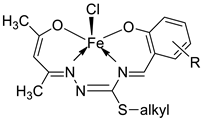

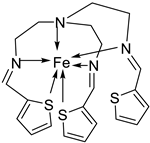

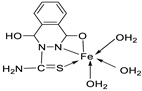

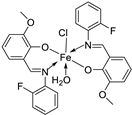

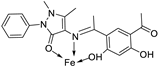

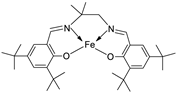

| 1. | 3, 4 |

|

EtOH Reflux, 2 h Stirring |

3 |

MCF-7 21.35±0.12 |

HepG-2 27.70±0.11 |

HCT-116 15.75± .07 |

[21] |

| 4 | 5.14± 0.05 | 6.75 ± 0.12 | 4.45±0.14 | |||||

| Doxorubicin | 4.10 ± 0.13 | 5.15 ± 0.07 | 4.35±0.15 | |||||

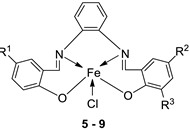

| 2. | 5 - 9 |  |

EtOH Reflux, 3 h |

KB | HepG-2 | [22] | ||

|

5 6 7 8 9 |

0.68± 0.05 3.25 ± 0.16 1.84 ± 0.10 2.76 ± 0.17 1.95 ± 0.13 |

0.83 ± 0.05 7.05 ± 0.25 6.07 ± 0.22 19.78 ± 1.07 2.38 ± 0.17 |

||||||

| Ellipticine |

1.14 ± 0.06 |

2.11 ± 0.12 | ||||||

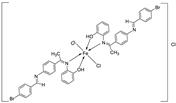

| 3. | 10 - 18 |

|

Stirring, 30 min |

K562 |

P3HR1 |

JURKAT |

[27] | |

| 10 | >25 | >25 | >25 | |||||

|

11 12 13 |

9.25 ± 0.42 22.24± 0.06 >25 |

5.61 ± 0.19 8.09 ± 0.62 >25 |

>25 >25 >25 |

|||||

|

14 15 16 |

4.81 ± 0.15 >25 14.05± 0.31 |

11.98± 0.69 22.4 ± 0.47 5.72 ± 0.28 |

22.79±0.54 >25 >25 |

|||||

|

17 18 |

5.04 ± 0.18 >25 |

11.47± 0.42 21.03± 0.39 |

22.0 ± 0.39 >25 |

|||||

| Imatinib | 9.67 ± 0.49 | 23.74± 1.02 | 3.73 ± 0.21 | |||||

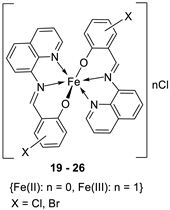

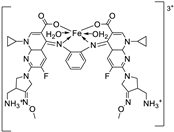

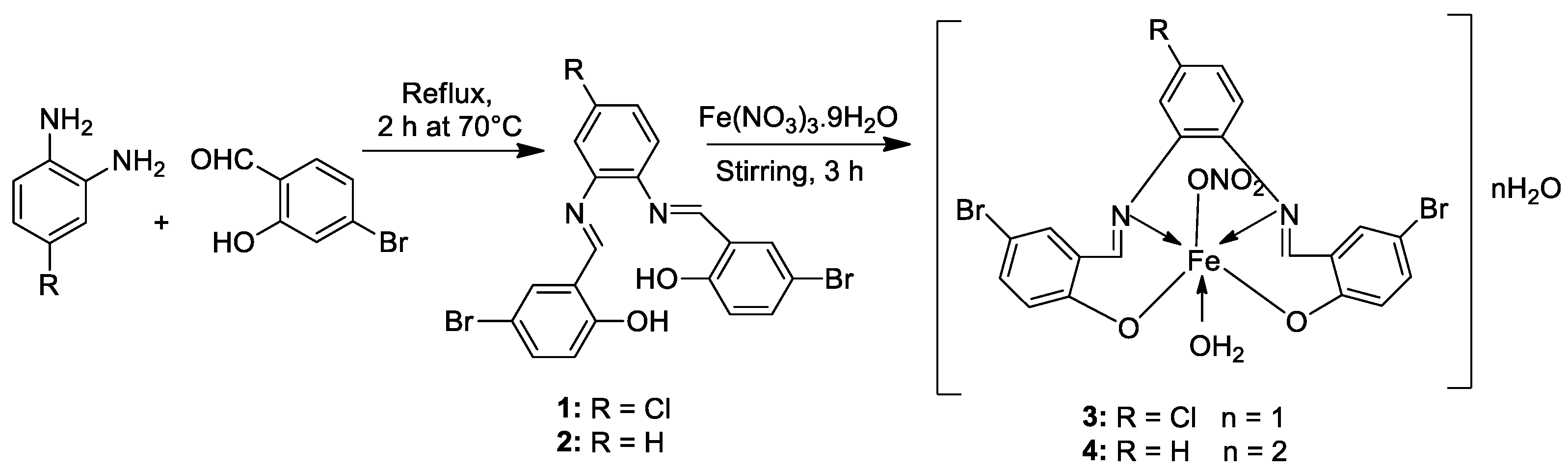

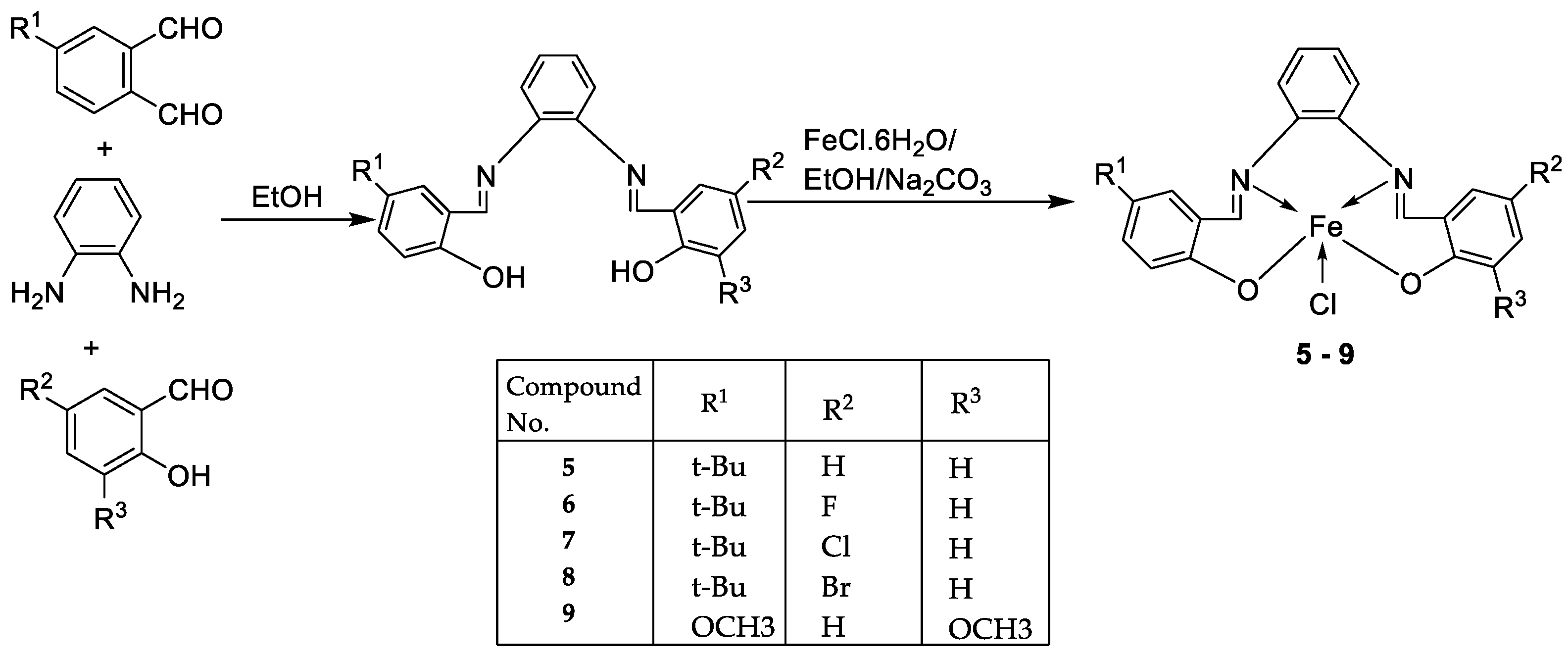

| 4. | 19 - 26 |  |

0°C, 7 days |

19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 |

A549 30 ± 1.1 30 ± 7.7 28 ± 2.0 28 ± 2.0 28 ± 2.0 10 ± 2.1 34 ± 4.7 32 ± 1.5 |

[28] | ||

| Etoposide | 19 ± 1.3 | |||||||

| Cisplatin | 16 ± 1.9 | |||||||

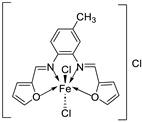

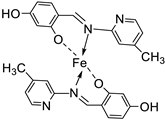

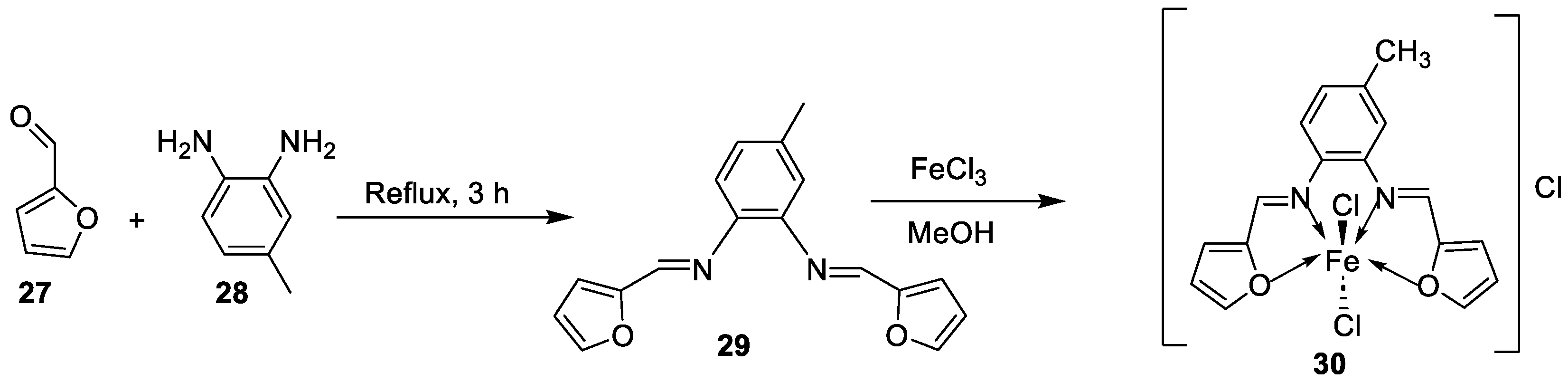

| 5. | 30 |  |

Reflux, 3 h Stirring, 2 h |

Hep-G2 |

[29] | |||

| 30 | 7.31 | |||||||

| Vinblastine | 2.93 | |||||||

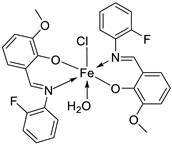

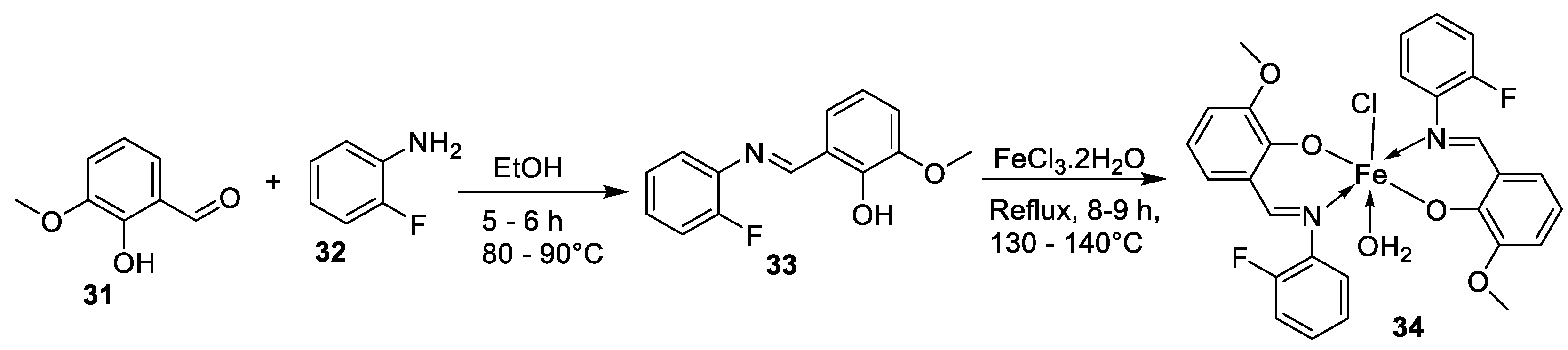

| 6. | 34 |

|

Reflux, 8-9 h |

|

Hela | MiaPaCa-2 | B16F10 | [30] |

| 34 | 106.26 ± 0.5 | 112.13± 0.6 | 104.15± 1.2 | |||||

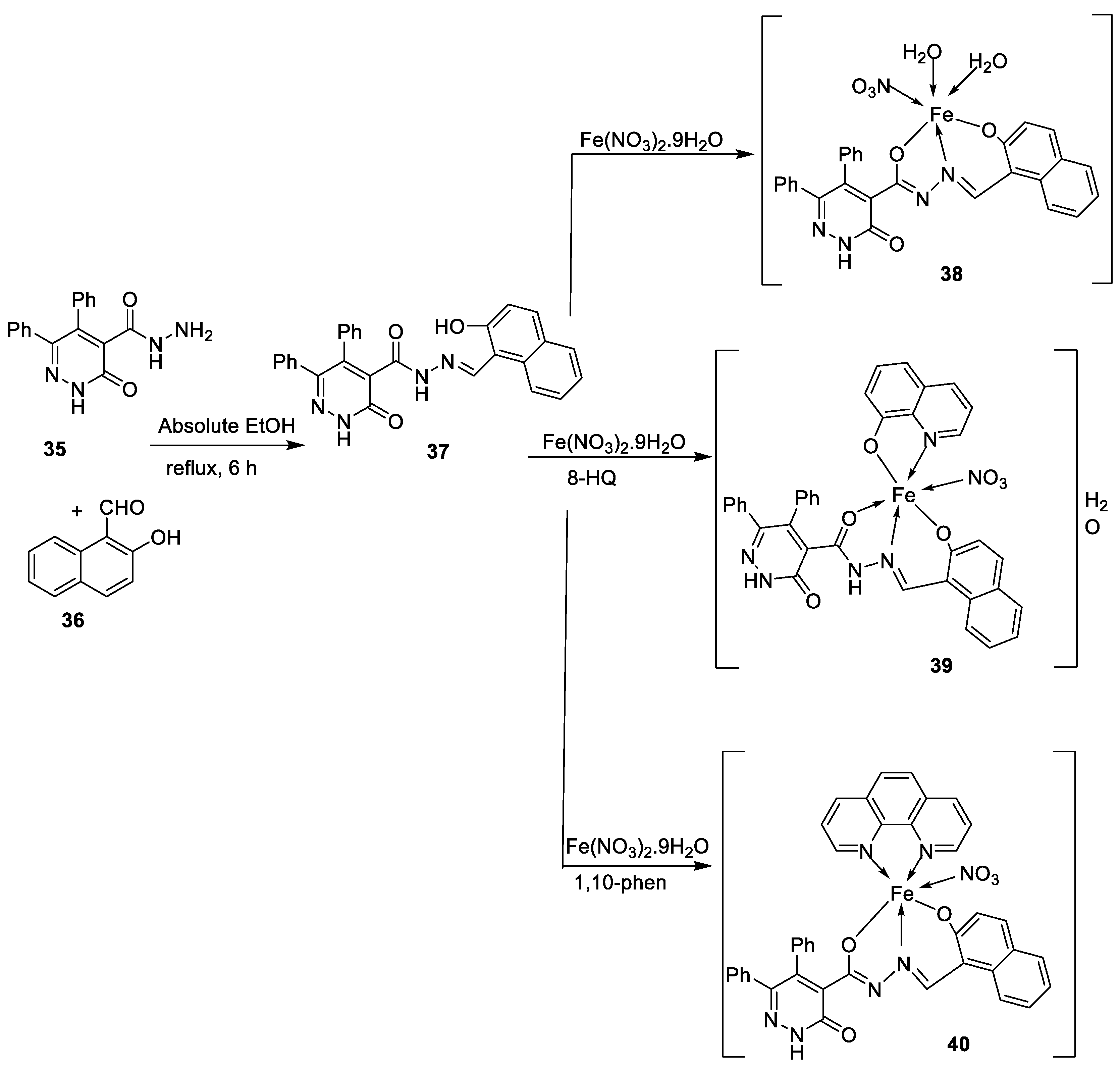

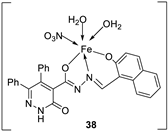

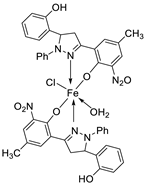

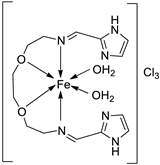

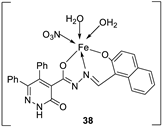

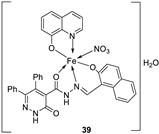

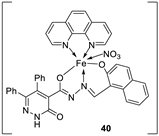

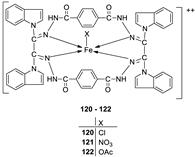

| 7. | 38 - 40 |

|

Stir, 2 h Reflux, 12 – 15 h |

37 38 39 40 Cisplatin |

Hep-G2 |

[31] | ||

| 3.8058.00 R R 3.27 | ||||||||

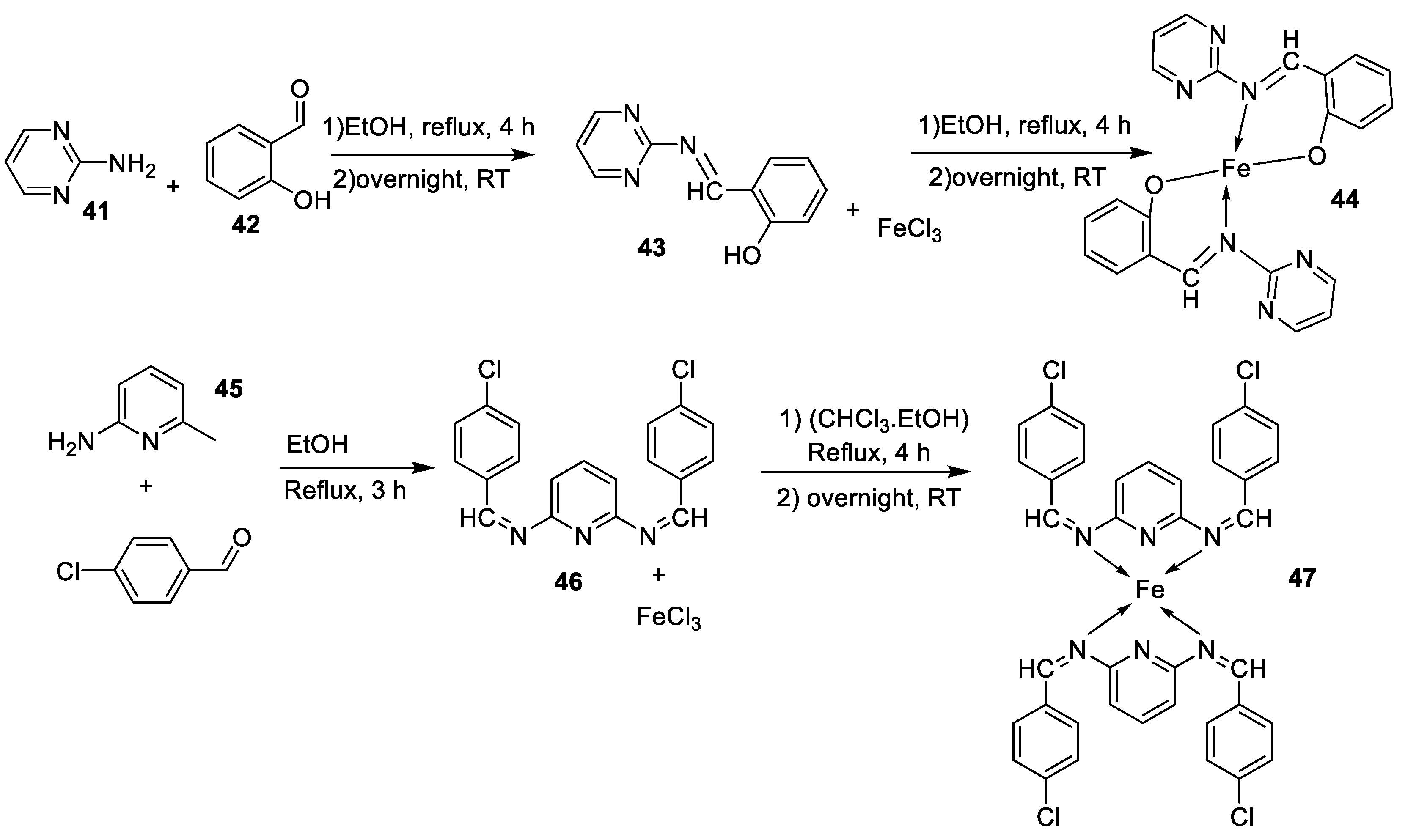

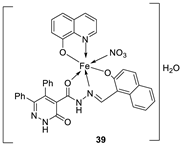

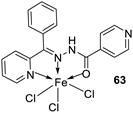

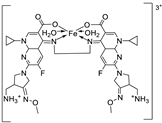

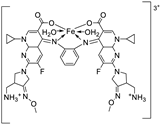

| 8. |

44 45 46 47 |

|

Reflux, 3 – 4 h |

44 45 46 47 |

L20B |

[32] | ||

| 8.70 13.20 18.4 22.9 | ||||||||

2.2. Imine-iron complexes as antimicrobial agents

| No. |

Complex No. | Structures of synthesized complexes | Reaction conditions | Biological activity Antimicrobial | Ref. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

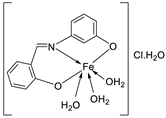

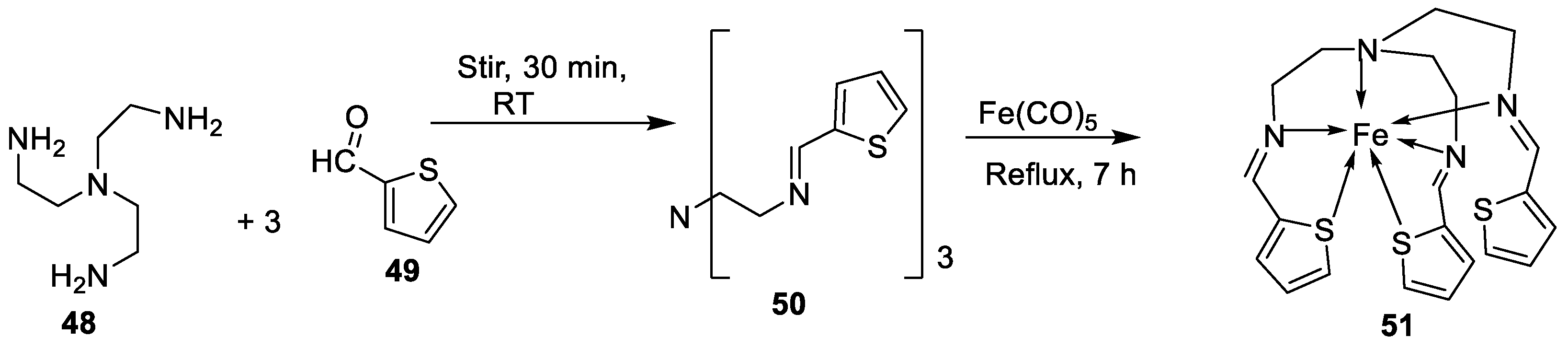

| 1. | 51 |  |

Stirring, 30 min Reflux, 7 h |

Zone of inhibition, mm | [40] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| S. aureus |

E. coli |

P. aeruginosa | B. cereus | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 50 | 11 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 51 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 29 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tetracycline | 9 | 10 | 12 | 11 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

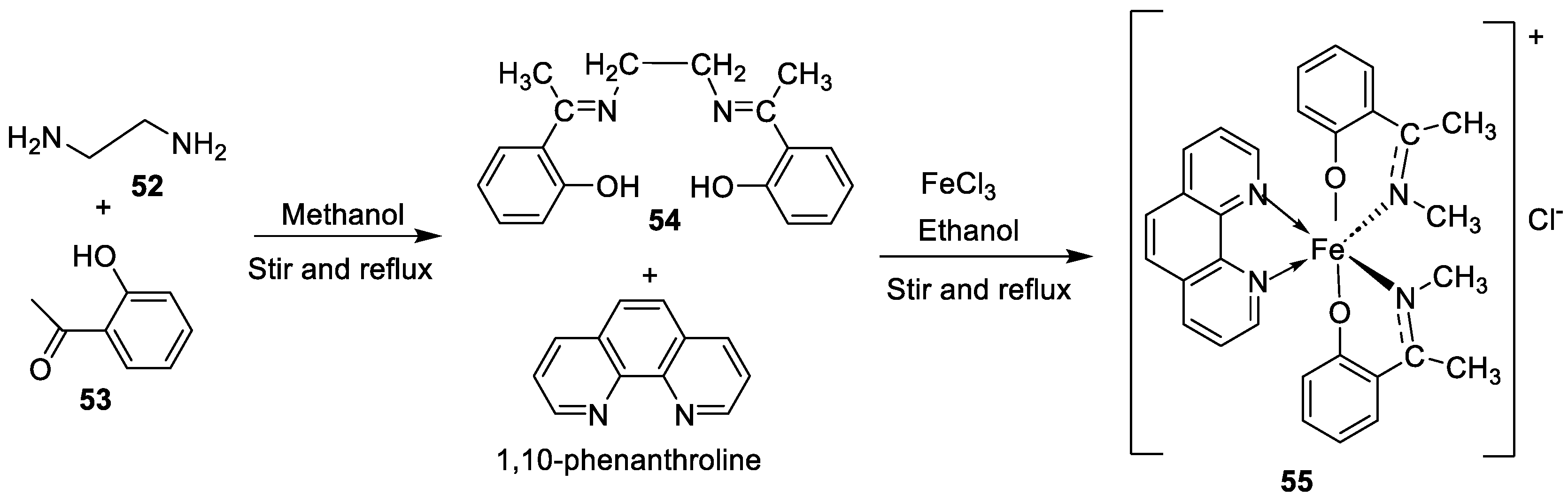

| 2. | 55 |  |

Stirring, 1-2 h Reflux, 2-11 h |

Zone of inhibition, mm | [42] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| E. coli | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 54 | 23 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 55 | 29 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Amoxicillin | 41 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chloramphenicol | 39 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3. |

3 4 |

|

Reflux, 2 h | Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)/µg/mL | [21] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bacteria | Fungi | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

S. marcescence |

E. coli |

M. luteus |

G. candidum |

A. flavus |

F. oxysporum |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

1 2 3 |

7.25 5.50 3.75 |

7.25 6.25 4.25 |

6.25 4.75 3.00 |

6.75 5.25 4.00 |

8.00 6.75 4.50 |

7.50 6.25 4.25 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | 3.25 | 3.50 | 2.50 | 3.00 | 3.75 | 3.50 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

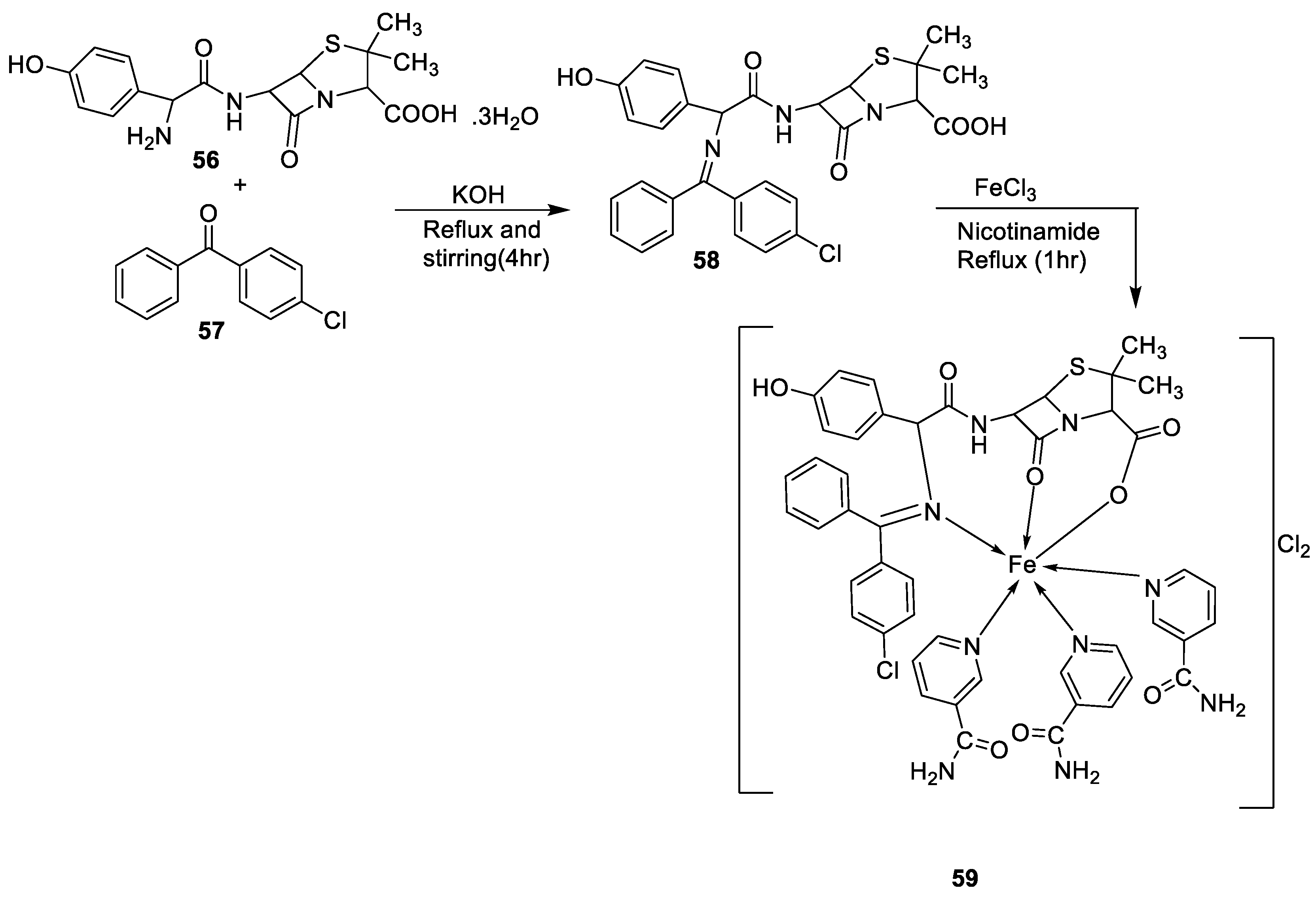

| 4. | 59 |

|

Stirring Reflux, 1 h |

Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)/µg/mL |

[47] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| E. coli | Pseudomonas | S. aureus | Bacillus | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

58 59 |

2.5 25 |

8 R |

15 R |

17 **R |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

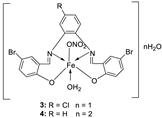

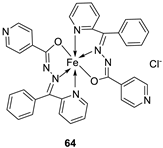

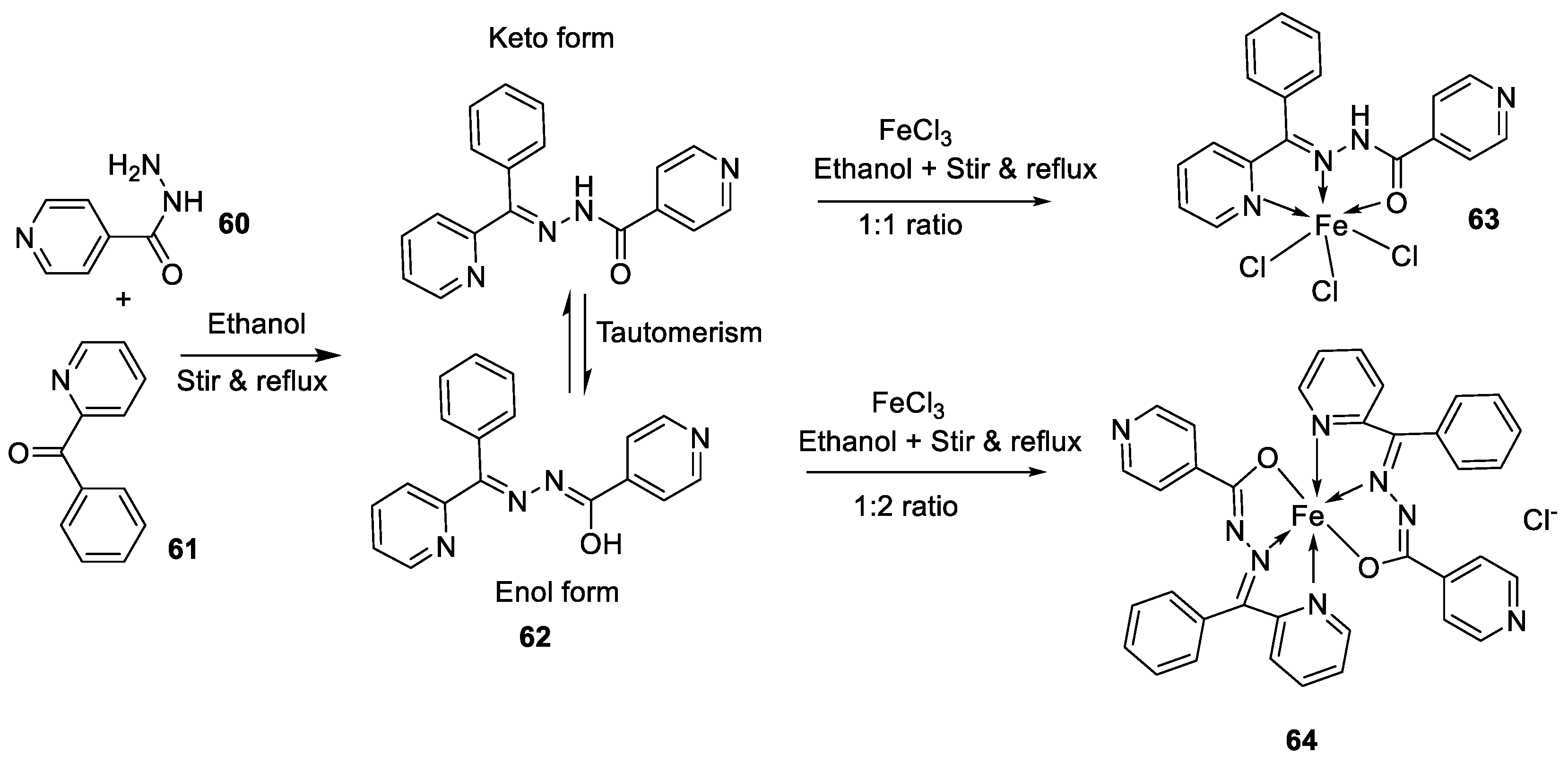

| 5. |

63 64 |

|

Stirring, 1 h Reflux, 9 h |

Zone of inhibition, mm | [48] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bacillus subtilis | E. coli | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 62 | 11 | 15 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 63 | 12 | 11 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 64 | 14 | 18 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Amoxicillin | 16 | 20 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

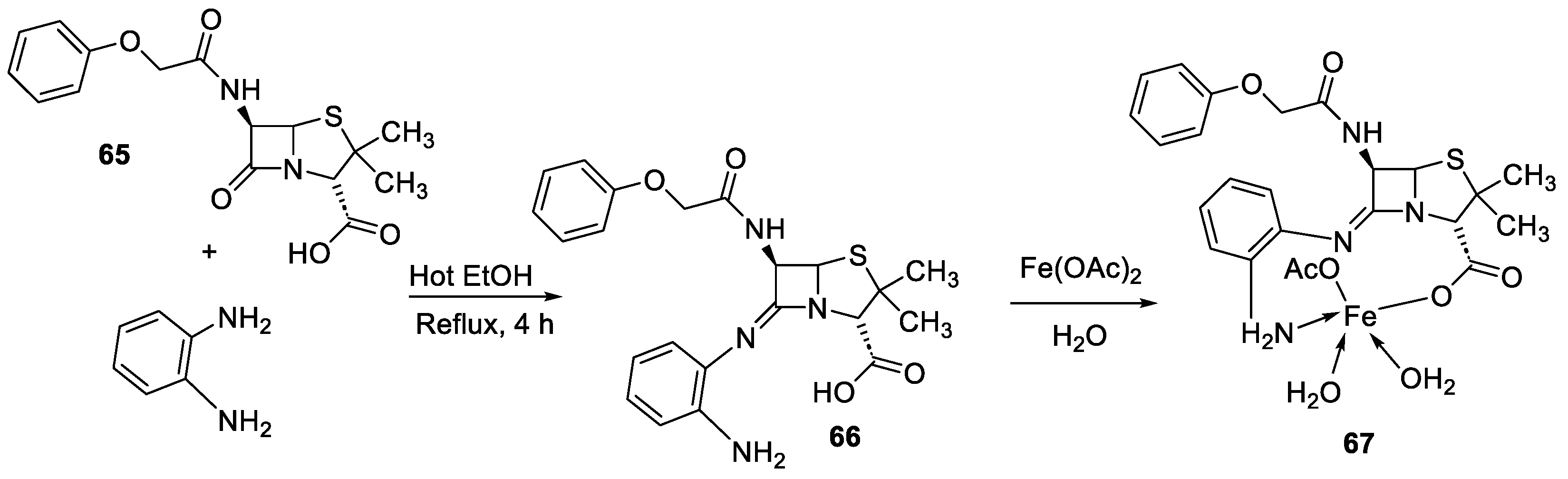

| 6. | 67 |

|

Reflux, 5 h | Zone of inhibition, mm | [65] |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| S. v | E. sp | S. a | E. f | MRSA | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 65 | 15 | 24 | 16 | 17 | R** | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

67 Standard |

20 19 |

30 36 |

25 45 |

22 36 |

15 R |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

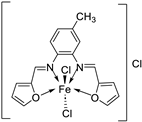

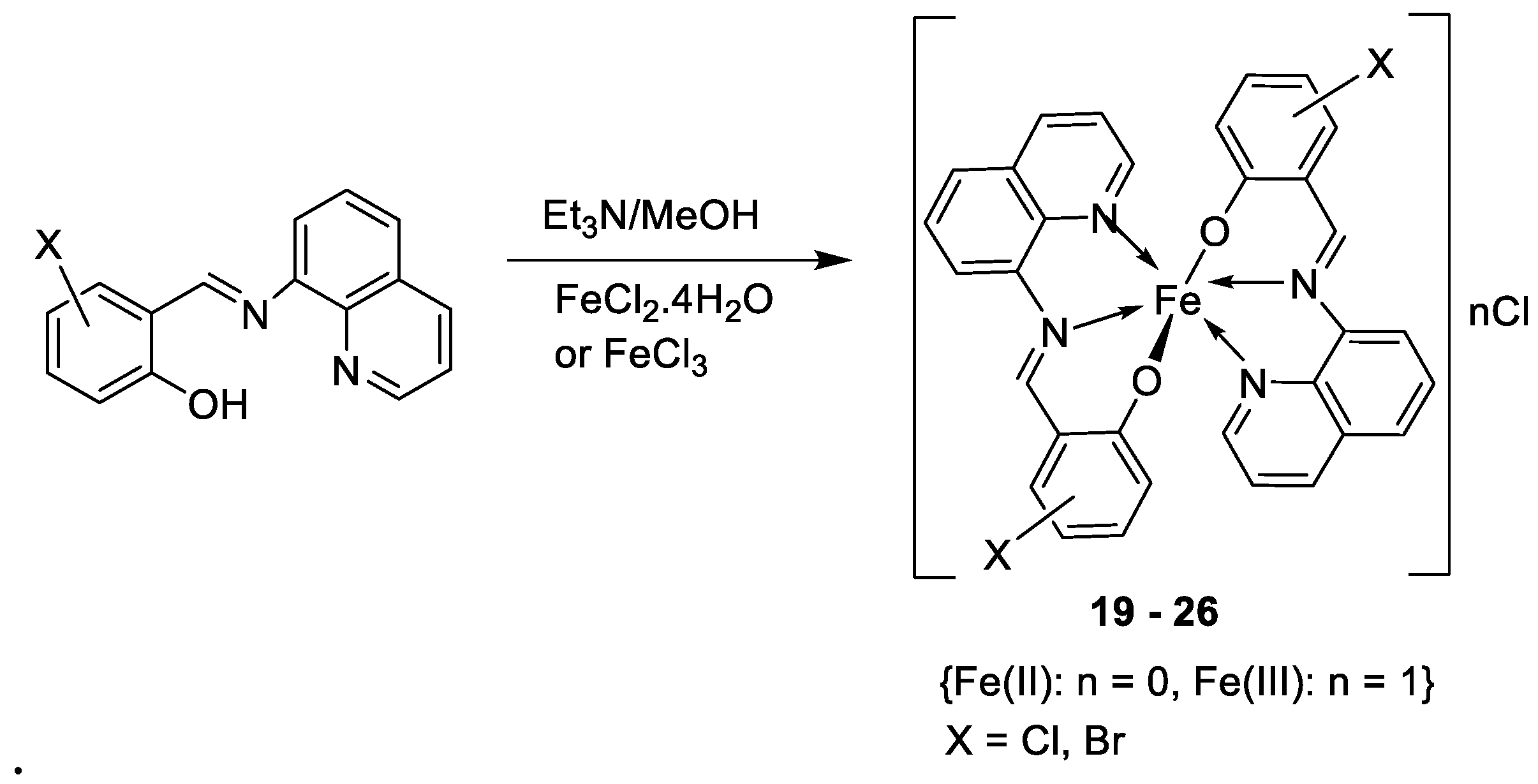

| 7. | 68 |  |

Reflux, 4 h | Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)/µg/mL | [10] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| C. albicans | C. neoformans | S. aureus | B. cereus | E. coli | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 68 | 0.0156 | 0.0078 | 0.0625 | 0.0312 | 0.0625 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nystatin | 0.032 | 0.032 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Miconazole Furacillinum Ciprofloxacin Amikacin |

0.016 | 0.0162 |

0.0046 0.001 |

0.0046 0.0003 |

0.0046 0.008 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8.. | 69 |  |

Reflux, 2 h | Zone of inhibition, mm | [51] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| E. coli | E. aerogenes | C. butyrium | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ligand | 14 | 12 | 12 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

69 Standard |

12 11 |

10 7 |

9 9 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

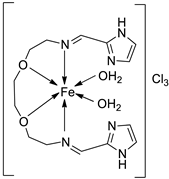

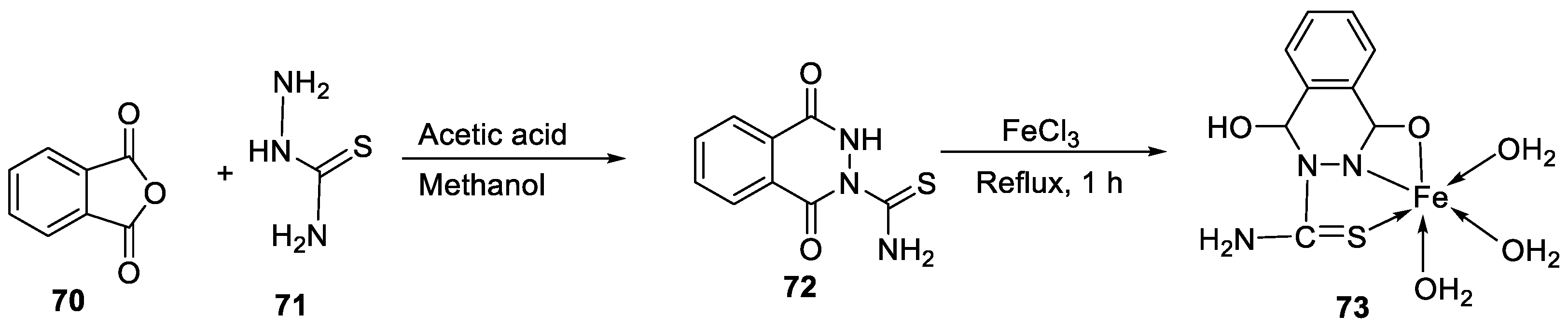

| 9. | 73 |

|

Stir and reflux, 1 h | Zone of inhibition, mm | [52] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| S. pneumonia | S. aureus | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 72 | 7-10 | 1-3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 73 | 7-10 | 7-10 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

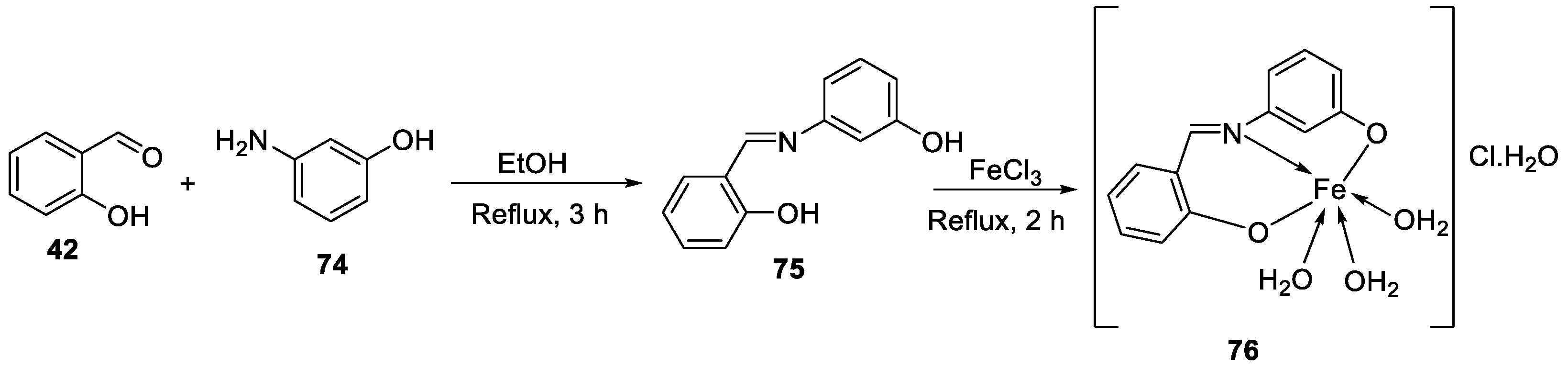

| 10. | 76 |  |

Stir and reflux, 2 h | Zone of inhibition, mm | [4] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| S. aureus | E. coli | P. aeruginosa |

C. albicans |

A. fumigatus |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 75 | 15 | 14 | 16 | 13 | 15 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

76 |

16 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 18 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ampicillin Gentamycin Amphotericin |

23 |

19 |

16 |

25 |

23 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

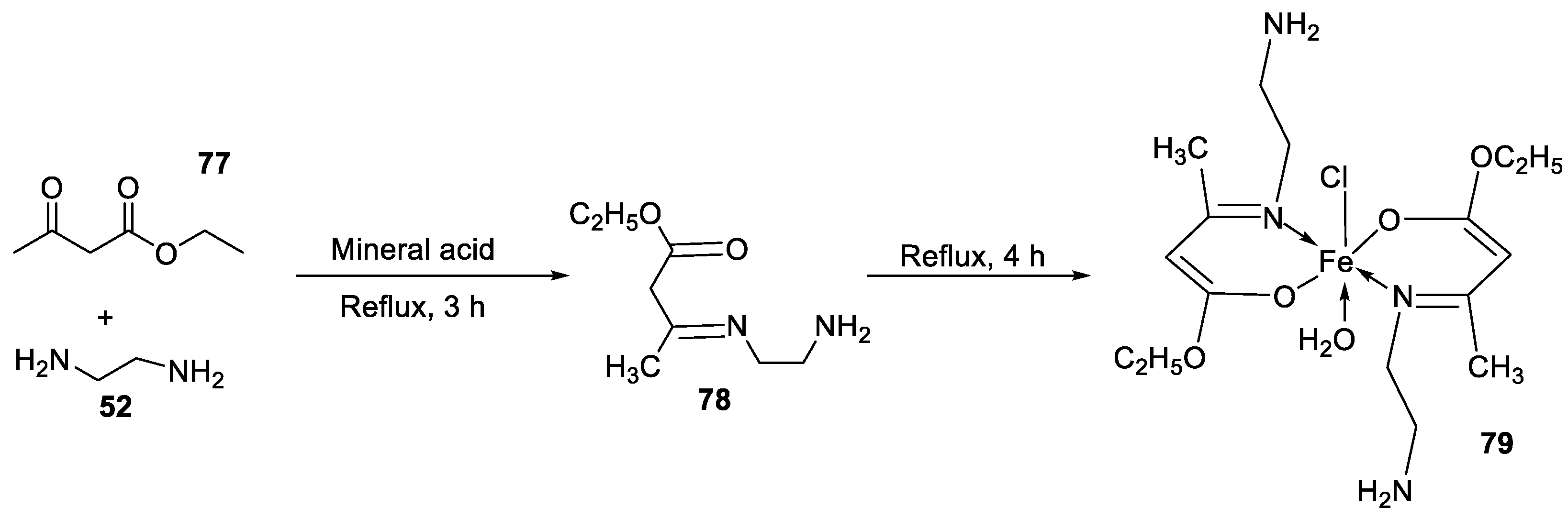

| 11. | 79 |

|

Reflux, 4 h | Zone of inhibition, mm | [53] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| S. aureus | P. aeruginosa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 78 | 8 | 6 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 79 | 14 | 11 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ampicillin Choloramphenicol |

14 |

8 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

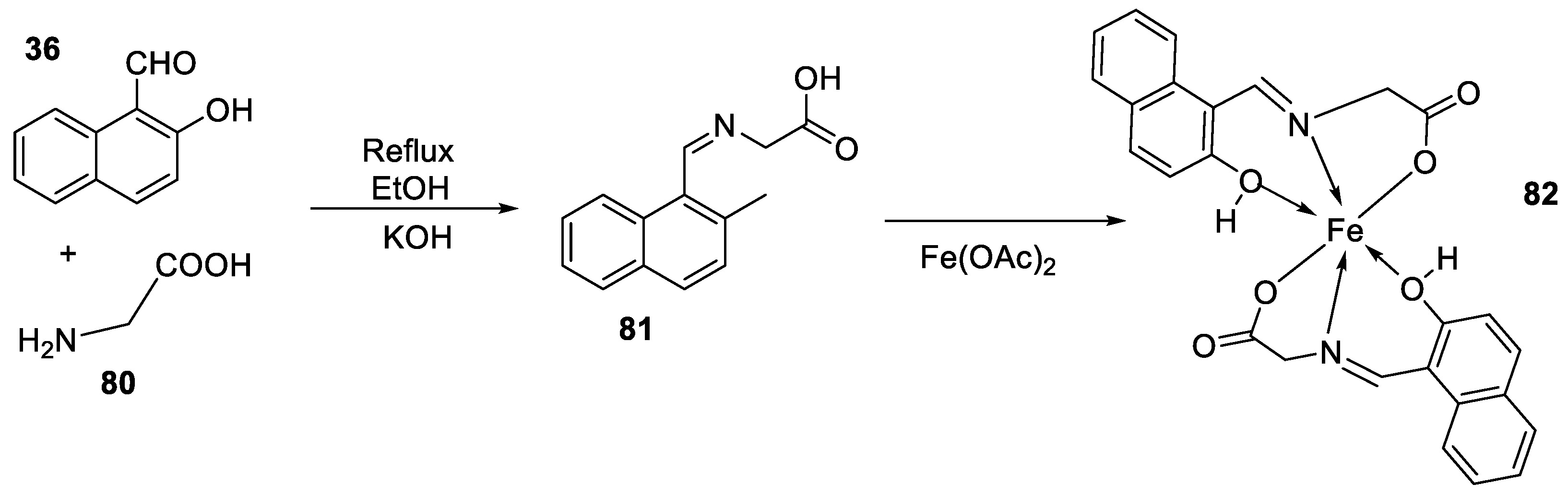

| 12. | 82 |

|

Stir (overnight) | Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)/µg/mL | [2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| E. coli | S. aureus | C. albicans | A. niger | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 82 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gentamicin Fluconazole |

10 | 10 |

20 |

20 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 13. | 83 |

|

Reflux and stirring, 3 h | Zone of inhibition, mm | [54] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| E. coli |

P. aeruginosa |

S. aureus |

C. albicans |

F. solani |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ligand | R | R | 12 | **R | **R | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 83 | 14 | 8 | 12 | 7 | 12 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

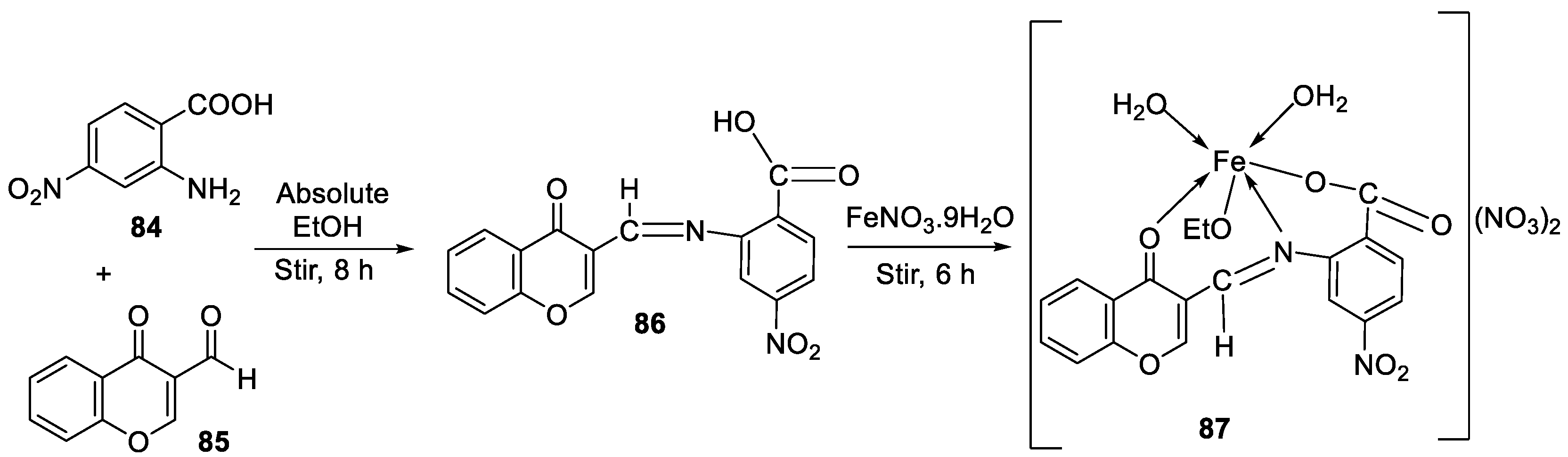

| 14. | 87 |

|

Stirring, 6 h | Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)/µg/mL | [3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| E. coli | C. albicans | P. vulgaris | K. pneumonia | S. aureus | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 86 | 12.5 | 4 | >50 | 1 | >50 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 87 | ˃50 | 8 | >50 | >50 | >50 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Doxymycin Fluconazole |

2 |

2 |

2 |

4 |

4 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

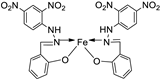

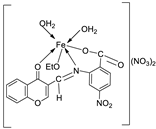

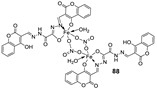

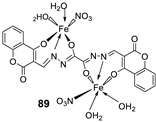

| 15. |

88 89 |

|

Stir, 30 min Reflux, 6 h |

Zone of inhibition, mm | [55] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| S. aureus | P. phaseolicol | F. oxysporium | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ligand | 22 ± 0.2 | 13 ± 0.1 | 17 ± 0.2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 88 | 37 ± 0.4 | 26 ± 0.1 | 31 ± 0.2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 89 | 32 ± 0.2 | 23 ± 0.1 | 30 ± 0.2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cephalothin Chloramphenicol Cycloheximide |

42 |

36 |

40 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16. |

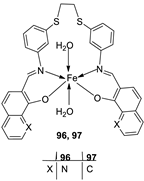

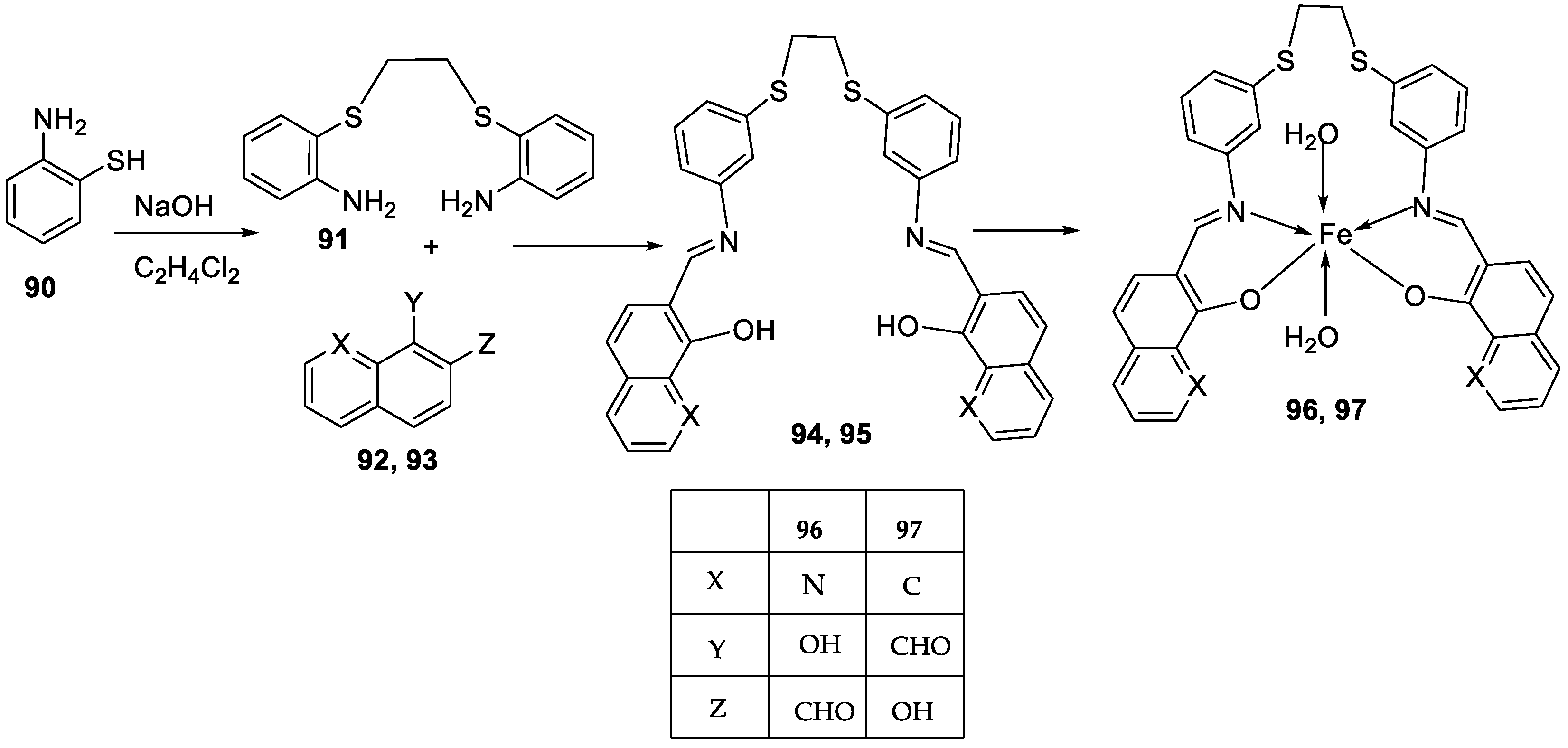

96 97 |

|

Reflux and stirring, 4-5 h | Zone of inhibition, mm | [57] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| S. epidermidis | E. faecalis |

S. aureus |

P. mirabilis |

C. albicans |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 94 | 5 | 9 | 7 | **R | **R | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 95 | 6 | 8 | 9 | **R | **R | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 96 | 14 | 15 | 12 | 8 | **R | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 97 | 12 | 8 | 7 | 22 | **R | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Amoxicillin | 28 | 26 | 27 | 44 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

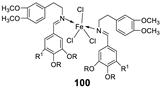

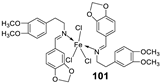

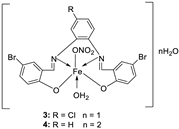

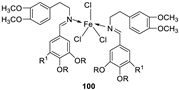

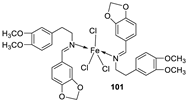

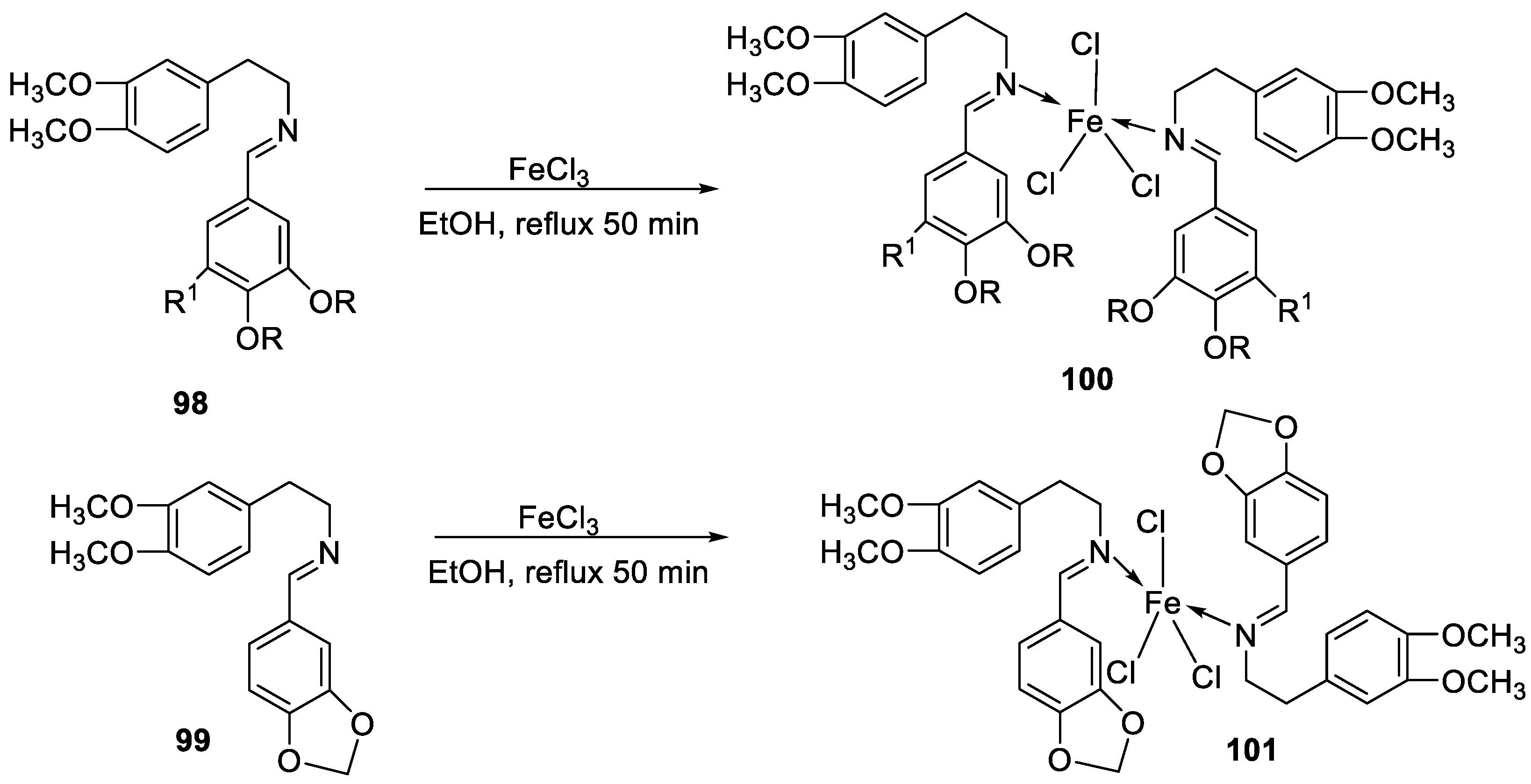

| 17. |

100 101 |

|

Reflux and stirring 50 min | Zone of inhibition, mm | [59] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| E. coli | P. aeruginosa |

C. albicans |

S. aureus |

C. glabrata |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 98 | 11 | 15 | 15 | 19 | 11 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 99 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 18 | 12 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 100 | 22 | 19 | 20 | 16 | <10 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 101 | 20 | 16 | 13 | 20 | 12 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tetracycline Nystatin |

25 | 20 |

19 |

23 |

16 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

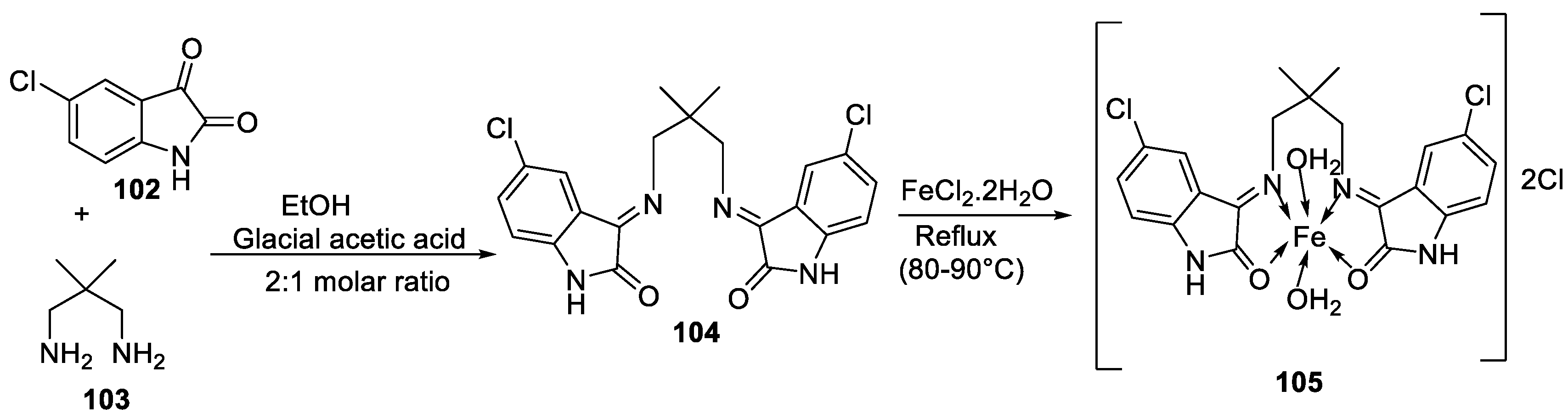

| 18. | 105 |  |

Reflux, 15 h | Zone of inhibition, mm | [60] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| E. coli | S. epidermidis | A. niger | A. flavus | C. lunata | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 104 | **R | 6 | 11 | 9 | 10 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 105 | 15 | 15 | 16 | 14 | 15 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 19. | 34 |  |

Reflux, 8-9 h | Zone of inhibition, mm | [30] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bacillus | Staphylococcus | E. coli |

S. rolfsii |

M. phaseolina |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 33 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 34 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 14 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Streptomycin Mancozeb |

9 | 11 | 5 |

18 |

24 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

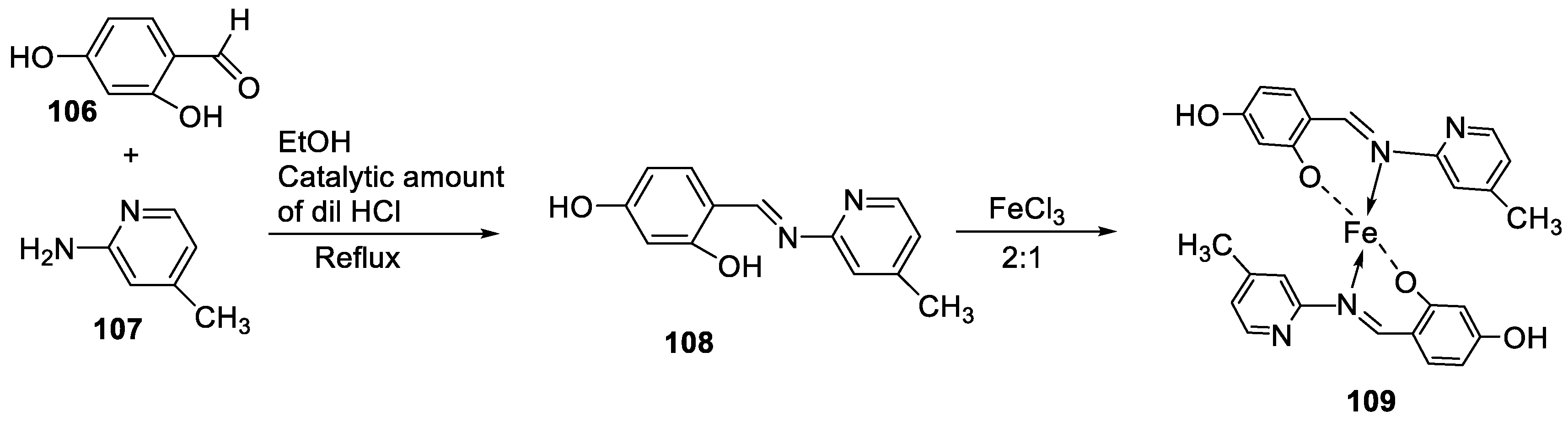

| 20. | 109 |  |

Reflux, 4-5 h | Zone of inhibition, mm | [61] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| S. aureus | E. coli | A. niger | C. albicans | F. moniliforme | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 109 | 3.02 | **R | 15.80 | 7.44 | **R | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chloramphenicol Amphotericin |

15.11 | 25.44 |

15.78 |

23.23 |

12.58 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 21. | 110 |  |

Reflux, 15-16 h | Zone of inhibition, mm | [62] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| S. pyrogenes | E. coli | S. typhi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 110 | 25 | 16 | 19 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

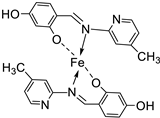

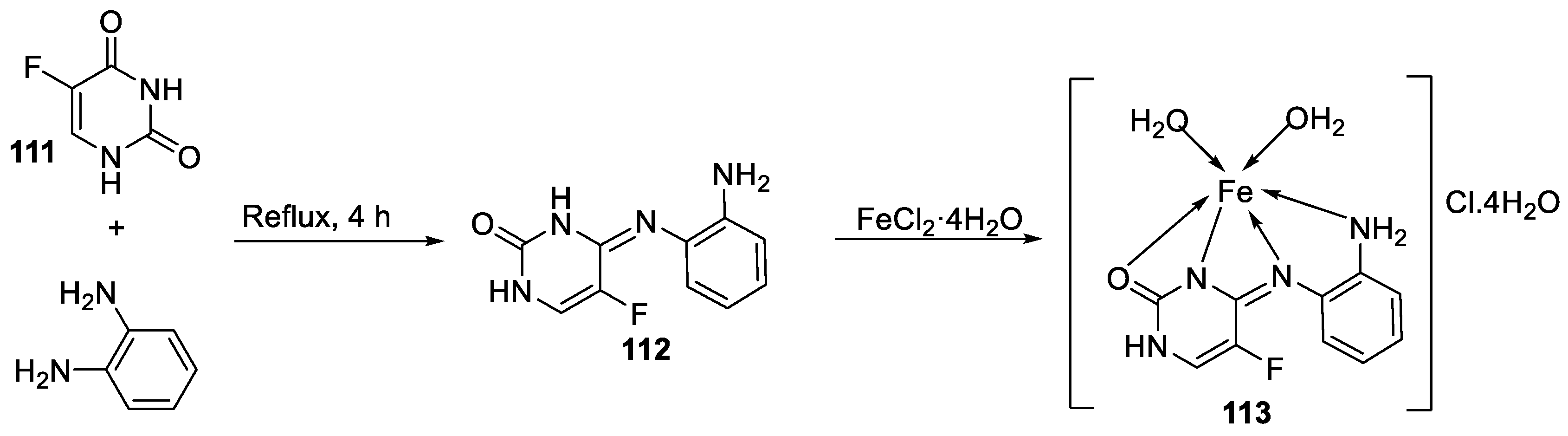

| 22. | 113 | Reflux, 6 h | Zone of inhibition, mm(concentration,mg/ml) | [64] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

B. subtilis | B. megaterium |

P. aeroginosa |

K. pneumonia | E. aerogenes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 111 | 40±0.47(0.2) | 34±0.81(0.2) | 42±1.24(1) | 36±0.47(0.2) | 45 ± 0.00 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 112 | 30 ± 0.81(0.2) | 22±0.81(0.5) | 33±0.81(0.2) | **R | 28 ± 0.00 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 113 | 21 ± 0.00(0.2) | **R | 36±1.24(1) | **R | **R | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Erythromycin | 20 ± 0.00 | 25±0.47 | 19±0.47 | 19±0.00 | 27 ± 1.24 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

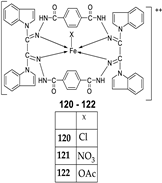

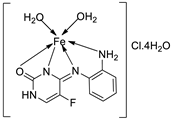

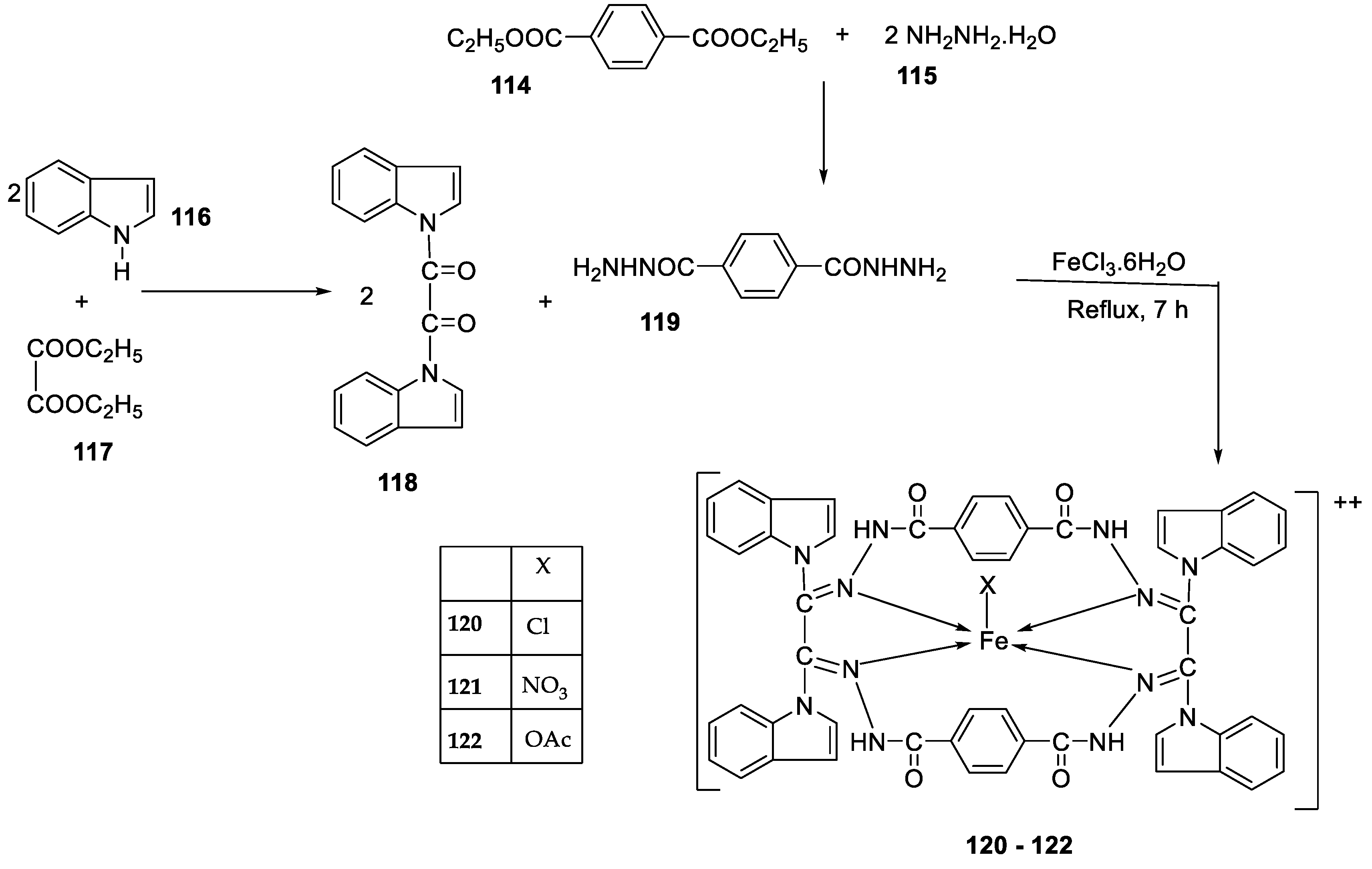

| 23. |

120 121 122 |

|

Reflux, 8 h | Zone of inhibition, mm | [66] |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

S. aureus |

P. aureginosa | E. coli |

S. typhii |

Aspergillus sp. |

P. sp. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 119 | 36 | 08 | 10 | 10 | 48 | 29 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 120 | 30 | 36 | 41 | 42 | 68 | 61 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 121 | 24 | 25 | 22 | 28 | 51 | 54 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 122 | 62 | 65 | 33 | 35 | 80 | 66 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Imipenem Miconazole |

100 | 100 | 100 |

100 |

57 |

65 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 24. | 123 |  |

Reflux, 3 h | Zone of inhibition, mm | [35] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| X. campestris | B. megaterium | C. michiganensis | M. fructicola |

P. digitatum |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ligand | 30 | 28 | 32 | 36.0 ± 3.1 | 28.0±3.5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 123 | 26 | 19 | 20 | 62.5 ± 6.2 | 62.5 ± 8.2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tetracycline Azoxystrobin |

34 | 28 | 30 |

45.3 ± 2.1 |

58.1 ± 1.2 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 25. | 124 |

|

Reflux, 3 h | Zone of inhibition, mm (concentraton, µg/ml) | [69] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| E. coli | B. cereus | P. fluorescens |

B. cinerea |

A. flavus |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ligand | 20 | 12 | 11 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.00 ±0.0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 124 | 12 | 12 | 18 | 6.7 ± 2.3 | 6.7±2.6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tetracycline Cycloheximide |

14 | 10 | 8 |

42.2±2.6 |

9.7±3.0 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 26. | 30 |  |

Stir and reflux, 4 h | Zone of inhibition, mm | [29] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| S. aureus | B. subtilis | E. coli | C. albicans | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ligand | 19 | 25 | 24 | 25 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 30 | 17 | 16 | 19 | 15 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gentamycin Ketoconazole |

24 | 26 | 30 |

20 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 27. | 125 |  |

Stirring, Reflux, 1 h | Zone of inhibition, mm | [72] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| S. aureus | E. coli | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ligand | 0.00 | 9 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 125 | 10 | 10 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Amikacin | 10 | 6 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 28. |

38 39 40 |

|

Stirring, 2 h Reflux, 12 – 15 h |

Zone of inhibition, mm | [31] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| S. typhimurium | C. albicans | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ligand | **R | 8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 38 | **R | 14 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 39 | 15 | 22 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 40 | **R | R | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cephalothin | 36 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cycloheximide | 35 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

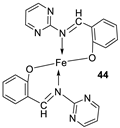

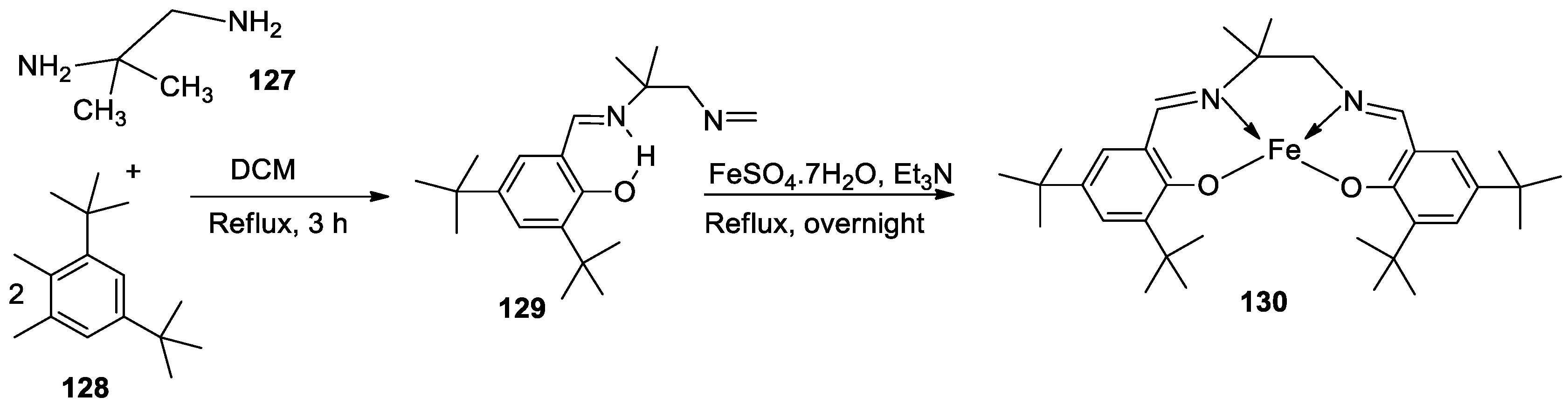

| 29. | 129 |  |

Stirring and reflux 1 h | Zone of inhibition, mm/mg | [75] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| E. coli | S. aureus | C. albicans | A. flavus | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 128 | 14 | 12 | 10 | 0 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 129 | 13 | 11 | 12 | 14 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Amikacin | 6 | 10 | - | - | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ketoconazole | - | - | 9 | 8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 30. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

2.3. Imine-iron complexes as antioxidants

| Entry No. | Complex No. | Structures | Reaction Condition | Antioxidant activity (IC50/µg/mL) | Ref. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. |

3 4 |

|

Reflux (2 h) | DPPH | [21] | |||||

| 1 | 45 | |||||||||

| 3 | 22 | |||||||||

| 2 | 53 | |||||||||

| 4 | 32 | |||||||||

| Vit C | 55 | |||||||||

|

DPPH | [59] | ||||||||

| 2. |

100 101 |

Reflux and stirring (50 min) | 98 | 1.23 | ||||||

| 100 | 1.70 | |||||||||

| 99 | 1.02 | |||||||||

| 101 | 1.41 | |||||||||

| Vit C | 1.14 | |||||||||

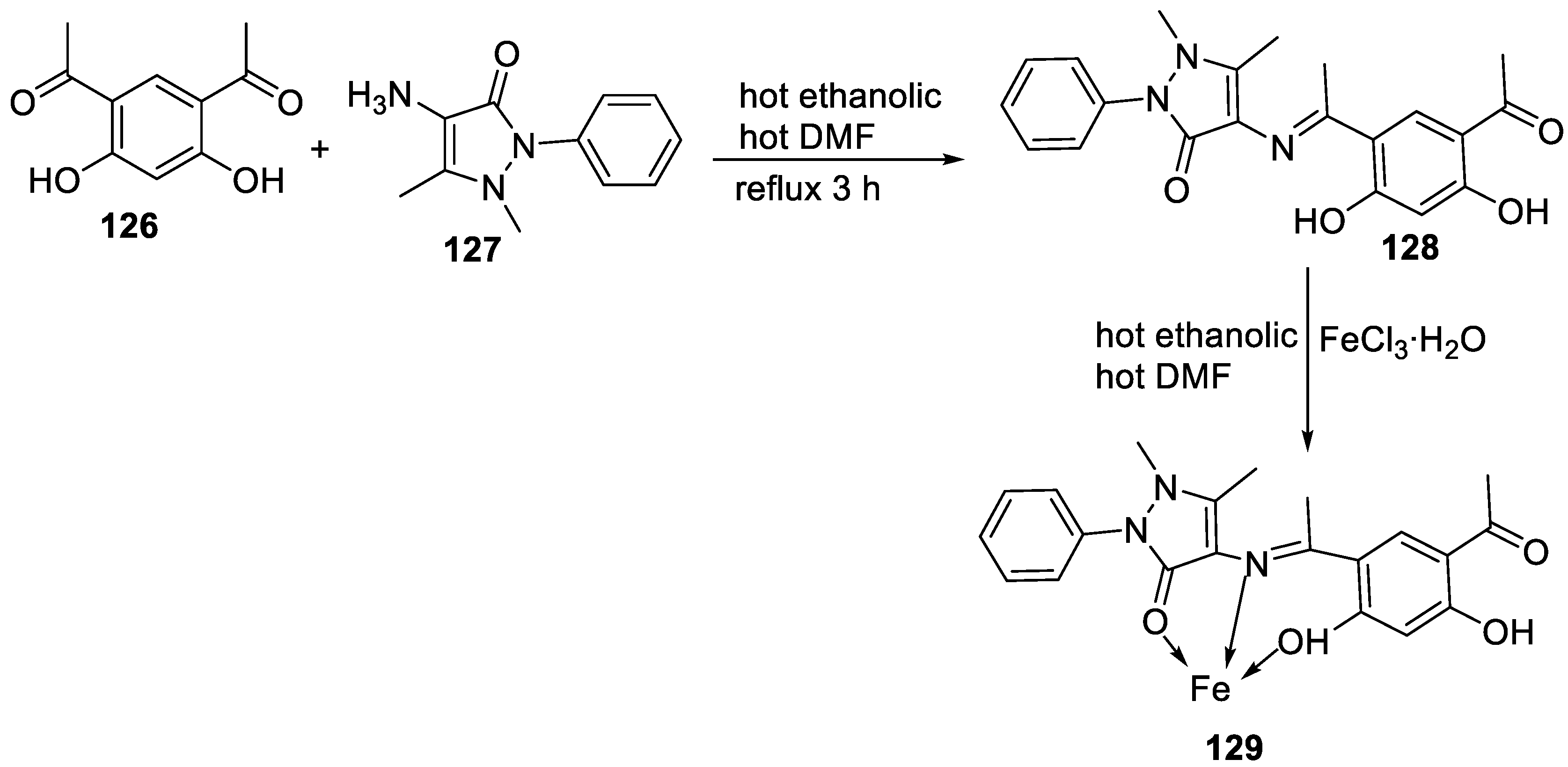

| 3. | 126 |  |

Reflux (10 min). Stirring (24 h) |

ABTS (734 nm) |

DPPH (517 nm) |

FRAP (700 nm) |

[80] | |||

| Ligand | 1.90 | 1.35 | 0.50 | |||||||

| 126 | 0.60 | 1.25 | 0.40 | |||||||

| Ascorbic acid | 0.00 | 0.10 | 2.10 | |||||||

| BHA | 0.00 | 0.18 | 2.90 | |||||||

| BHT | 0.00 | 0.31 | 2.30 | |||||||

| 4. | 130 |  |

Reflux and stir (overnight) | DPPH | H2O2 SA | FTC | HRSA | [81] | ||

| 129 | 53.55 ± 2.95 | 92.52± 0.07 | 48.81±5.04 | 63.43±5.66 | ||||||

| 130 | 44.65 ± 1.10 | 93.74 ± 0.43 | 9.47±2.191 | 30.29±0.81 | ||||||

| Trolox | 85.42 ± 0.04 | 91.80 ± 1.77 | 90.45±6.70 | 57.72±1.62 | ||||||

| BHA | 75.69 ± 0.11 | 92.97 ± 0.98 | 50.57±5.42 | 10.00±3.64 | ||||||

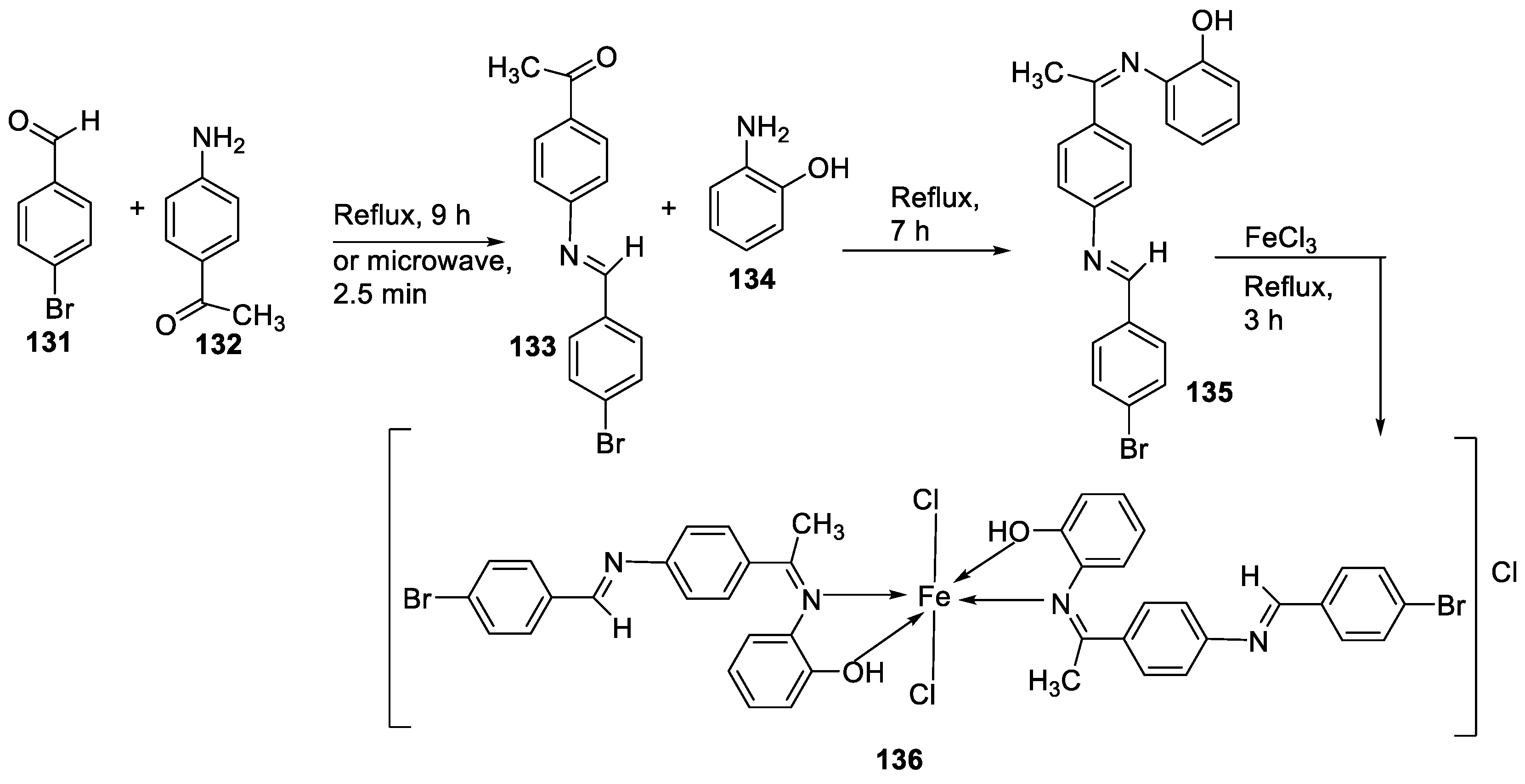

| 5. | 136 |  |

Reflux (3 h) |

135 136 Ascorbic acid |

DPPH (% scavenging) 24 49 82 |

[16] | ||||

| 6. | 124 | Reflux (3 h) |

Ligand 124 |

%RSA | [69] | |||||

|

169.7 164.6 |

|||||||||

| 7. | 109 |  |

Reflux (4-5 h) |

109 |

DPPH | [61] | ||||

| 1615.22 | ||||||||||

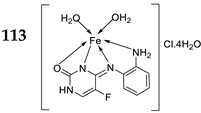

| 8. | 113 |  |

Reflux (6 h) |

111 112 113 BHT BHA |

DPPH 1.9 0.8 0.70 0.60 1.20 |

Total Anti Oxidant 0.64 0.62 0.61 0.60 0.44 |

FRAP 0.06 0.38 0.11 0.08 0.20 |

CUPRAC 0.30 3.50 1.20 3.20 3.10 |

[64] | |

2.4. Other pharmacological activities of the imine-iron complexes

| Entry No. | Complex No. | Structures | Reaction conditions | Biological activities | Ref | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

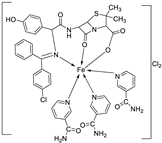

| 1. |

120 121 122 |

|

Reflux, 8 h | Anti-inflammatory activity | [66] | |

| 119 | 9.00 | |||||

| 120 | 28.50 | |||||

| 121 | 27.20 | |||||

| 122 | 31.10 | |||||

| Phenyl butazone | 18.20 | |||||

| 2. | 125 |  |

Stirring, Reflux, 1 h | Binding energy (kcal/mol) | [72] | |

| Ligand | −2.1 | |||||

| 125 | -8.5 |

|||||

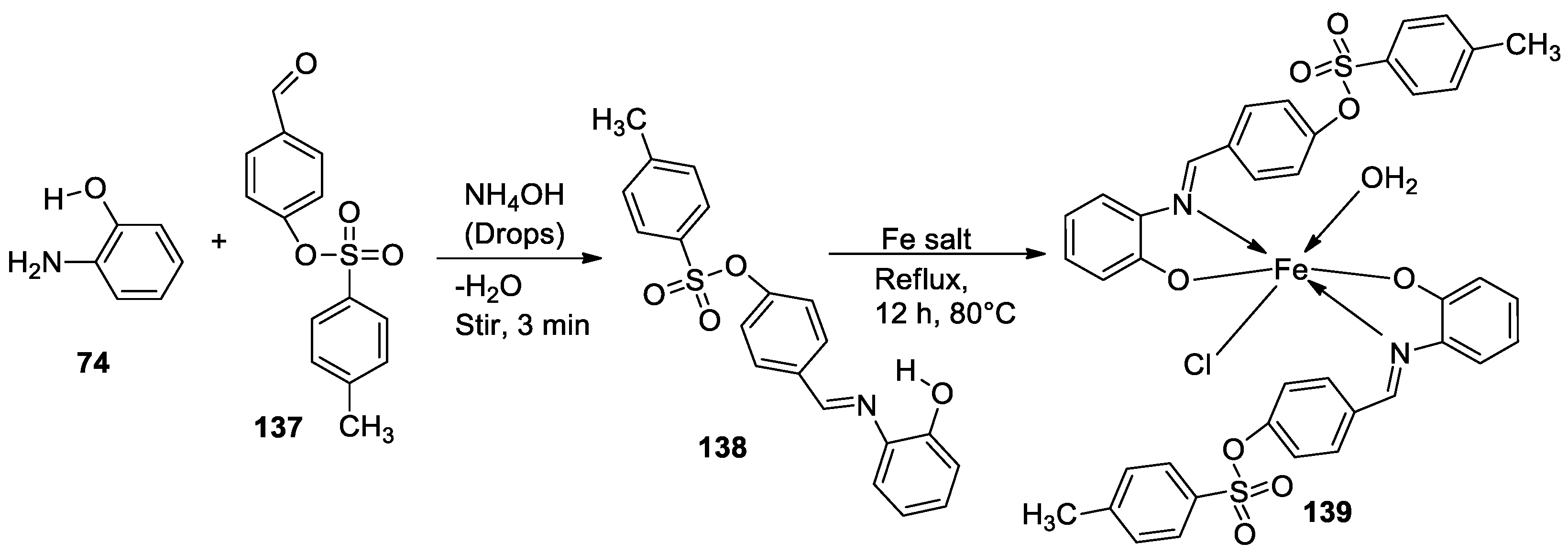

| 3. | 139 |  |

Reflux, 12 h |

138 |

%Inhibition of heat-induced denaturation of proteins 0.13 |

[83] |

| 139 | 0.70 | |||||

| Ibuprofen | 2.9 | |||||

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vija, K. J.; Abhishek, P.; Mohit, P.; Shweta, C.T.; Om, P.; Akansha, A.; Viveka, N. Schiff base metal complexes as a versatile catalyst: A review. Journal of Organometallic Chemistry 2023, Volume 999, 122825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manvatkar, V.D, Patle, R.Y, Meshram, P.H. et al. Azomethine-functionalized organic–inorganic framework: an overview. Chem. 2023, Pap. 77, 5641–5662. [CrossRef]

- Ying, K.L.; Mohand, M.; Dominik, M.; Guy B. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2023 145 (4), 2064-2069. [CrossRef]

- Chérifa, B.; Hana, F.; Amel, D.; Amel. D.; Abdesalem, K.; Abir, B.; Ahmad, S.D.; Tarek, R.; Rajesh, V.; Yacine, B. Schiff bases and their metal Complexes: A review on the history, synthesis, and applications, Inorganic Chemistry Communications. 2023, Volume 150, 110451. [CrossRef]

- El-Attar, M.S.; Elshafie., H.S.; Sadeek, S.A.; El-Farargy, A.F.; El-Desoky, S.I.; El-Shwiniy, W.H.; Camele, I. Biochemical Characterization and Antimicrobial Activity against Some Human or Phyto-Pathogens of New Diazonium Heterocyclic Metal Complexes. Chemistry & Biodiversity 2022, 19, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anjali Krishna, G. T.; Dhanya, M.; Shanty, A.A.; Raghu, K.G.; Mohanan, P.V. Transition metal complexes of imidazole derived Schiff bases: Antioxidant/anti-inflammatory/antimicrobial/enzyme inhibition and cytotoxicity properties. Journal of Molecular Structure 2023, Volume 1274, Part 1, 134384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Song, Q.; Jin, Y.; Feng, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, K. Metals. Basel, Switzerland. 2023, 13(2), 386.

- Sohtun, W.P.; Khamrang, T.; Kannan, A.; Balakrishnan, G.; Saravanan, D.; Akhbarsha, M.A.; Velusamy, M.; Palaniandavar, M. Iron(III) bis-complexes of Schiff bases of S -methyldithiocarbazates: Synthesis, structure, spectral and redox properties and cytotoxicity. Applied Organometallic Chemistry. 2020, Volume34, Issue5, e5593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukki, S.; Samya, B.; Akhtar, H. Significant photocytotoxic effect of an iron(iii) complex of a Schiff base ligand derived from vitamin B6 and thiosemicarbazide in visible light. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 29276–29284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, R. K.; Mariya, A.; Mishra, S. K. Synthesis and spectral (ir, nmr, fab-ms and xrd) characterization of lanthanide complexes containing bidentate schiff base derived from sulphadiazine and ovanillin. Int. j. basic appl. sci, 2011; Vol. 1, 1, 70–78. [Google Scholar]

- Basu, U.; Roy, M.; Chakravarty, A.R. Recent advances in the chemistry of iron-based chemotherapeutic agents. Coordination Chemistry Reviews. 2020, Vol. 417, 213339, 0010-8545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satya, DP.; Logesh, R.; Dhanabal, P.; Suresh, M.K. Importance of Iron Absorption in Human Health: An Overview. Current Nutrition & Food Science. 2021; 17(3).

- Kargar, H.; Fallah-Mehrjardi, M.; Behjatmanesh-Ardakani, R.; Munawar, K.S.; Ashfaq., M.; Tahir, M.N. Diverse coordination of isoniazid hydrazone Schiff base ligand towards iron (III): Synthesis, characterization, SC-XRD, HSA, QTAIM, MEP, NCI, NBO and DFT study. 2022; Vol. 1250, Part 2, p. 131691, 0022-2860. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.W.; Jeong, G-U.; Kim, M-C.; Kim, D.; Kim, S.; Han, S.S. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy. 2023, 48(10), 3931–3941. [CrossRef]

- Peterson, P.O.; Joannou, M.V.; Simmons, E.M.; Wisniewski, S.R.; Kim, J.; Chirik, P.J. ACS Catalysis. 2023, 13(4), 2443–2448. [Google Scholar]

- Hayder, M.; Hayder, A.M. In vitro antioxidant activity of new Schiff base ligand and its metal ion complexes. J. Pharm. Sci. & Res 2019, Vol. 11(5), 2051–2061. [Google Scholar]

- Yahaya, N.P.; Mukhtar, M.S. Synthesis, Characterization and Antibacterial Activity of Mixed Ligands of Schiff Base and Its Metal (II) Complexes Derived from Ampicilin, 3-Aminophenol and Benzaldehyde. Science Journal of Chemistry 2021, Vol. 9(Issue 1), 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antolovich, M.; Prenzler, P.D.; Patsalides, E.; McDonald, S.; Robards, K. Methods for testing antioxidant activity. Analyst. The Royal Society of Chemistry 2002, Vol. 27(Issue 1), 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharti, S.; Singh, S. Metal Based Drugs: Current Use and Future Potential. Der Pharmacia Lett. 2009, 1. (2) 39-51, 0975-5071.

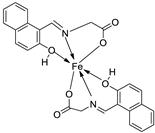

- Li, Y.; Qian, C.; Li, Y.; Yang, Y.; Lin, D.; Liu, X.; Chen, C. Syntheses, crystal structures of two Fe(III) Schiff base complexes with chelating o-vanillin aroylhydrazone and exploration of their bio-relevant activities, Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry. 2021, Vol. 218, 111405, 0162-0134. [CrossRef]

- El-Lateef, H.M.A.; Khalaf, M.M.; Shehata, M.R.; Abu-Dief, A.M. Fabrication, DFT Calculation, and Molecular Docking of Two Fe(III) Imine Chelates as Anti-COVID-19 and Pharmaceutical Drug Candidate. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022, 23, no. 7: 3994. [CrossRef]

- Bednarski, P.; Nguyen, Q.T.; Pham, T.P.N.; Nguyen, V.T. Synthesis, Characterization, and In Vitro Cytotoxicity of Unsymmetrical Tetradentate Schiff Base Cu(II) and Fe(III) Complexes. 2021, 6696344-2021.

- Zhao, W.L. Targeted therapy in T-cell malignancies: dysregulation of the cellular signaling pathways. 2010, Leukemia 24, 13–21. [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, M.S.; Lotfi, M.; Soltani, N.; Farmani, E.; Fernandez, J.H.O.; Akhlaghitehrani, S.; Mohammed, S.H.; Yasamineh, S.; Kalajahi, H.G.; Gholizadeh, O. Recent advances on high-efficiency of microRNAs in different types of lung cancer: a comprehensive review. Cancer Cell Int. 2023, 23(1):284. [CrossRef]

- Gujrati, H.; Ha, S.; Wang, B,D. Deregulated microRNAs Involved in Prostate Cancer Aggressiveness and Treatment Resistance Mechanisms. Cancers (Basel). 2023 Jun 10;15(12):3140. [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.X.; Zheng, Z.; Xue, W.; Zhao,M.Z.; Fei, X.C.; Wu, LL.; et al., Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 197241.

- Kalındemirtaş, F.D.; Kaya, B.; Bener, M.; Şahin, O.; Kuruca, S.; Demirci, T.B.; Ülküseven, B. Iron(III) complexes based on tetradentate thiosemicarbazones: Synthesis, characterization, radical scavenging activity and in vitro cytotoxicity on K562, P3HR1 and JURKAT cells. Applied organometallic chemistry 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongsuwan, S.; Chatwichien, J.; Pinchaipat, B. Synthesis, characterization and anticancer activity of Fe(II) and Fe(III) complexes containing N-(8-quinolyl)salicylaldimine Schiff base ligands. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2021, 26, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismail, B.A.; Nassar, D.A.; El–Wahab Abd, Z.H.; Ali, A.M.O. Synthesis, characterization, thermal, DFT computational studies and anticancer activity of furfural-type schiff base complexes. Journal of Molecular Structure. 2021, Vol. 1227, 129393, 0022-2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavitha, B.; Sravanthi, M.; Reddy, P.S. Studies on DNA binding, cleavage, molecular docking, antimicrobial and anticancer activities of Cr(III), Fe(III), Co(II) and Cu(II) complexes of o-vanillin and fluorobenzamine Schiff base ligand Applied Organometallic chemistry. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelrahman, M.S.A.; Omar, F.M.; Saleh, A.A.; El-ghamry, M.A. Synthesis, molecular modeling, and docking studies of a new pyridazinone-acid hydrazone ligand, and its nano metal complexes. Spectroscopy, thermal analysis, electrical properties, DNA cleavage, antitumor, and antimicrobial activities. Journal of Molecular Structure, 2022; Vol. 1251, 131947, 0022-2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhan, L.K.; Awad, M.A.; Kshash, A.H. Synthesis, Characterization and Evaluation Anti-cancer Activity of Fe(III), Co(II), Ni(II) and Cu(II) Complexes Derived from Heterocyclic Schiff bases Ligands. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research. 2019, Vol. 11(4), 1577–1581. [Google Scholar]

- Claudel, M.; Schwarte, J.V.; Fromm, K.M. Chemistry. Basel, Switzerland. 2020, 2(4), 849-899.

- Angelo, F.; Alysha, G.E.; Alex, K.; Hue, D.; Stefan, B.; Alice, E.B.; Mitchell, R.B.; Feng, C.; Dhirgam H.; Nicole Jung, A.P.K.; et al. T Blaskovich. JACS Au 2022 2 (10), 2277-2294. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.A.; Elshafie, H.S.; Sadeek, S.A.; Camele, I. Biochemical Characterization, Phytotoxic Effect and Antimicrobial Activity against Some Phytopathogens of New Gemifloxacin Schiff Base Metal Complexes. Chemistry & Biodiversity. Chem. Biodiversity. 2021, 18, 9, 1612-1872. [CrossRef]

- N. Raman, S.R.; Johnson, A.S. Transition metal complexes with Schiff-base ligands: 4- aminoantipyrine based derivatives-a review. J. Coord. Chem. 2009, 62, 691-709.

- Chohan, Z.H.; Shaikh, A.U.; Naseer, M.M.; Supran, C.T. In-vitro antibacterial, antifungal and cytotoxic properties of metal-based furanyl derived sulfonamides. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2006, 21, 771–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chohan, Z.H.; Arif, M.; Akhtar, M.A.; Supuran, C.T. Metal-Based Antibacterial and Antifungal Agents: Synthesis, Characterization, and In Vitro Biological Evaluation of Co(II), Cu(II), Ni(II), and Zn(II) Complexes With Amino Acid-Derived Compounds. Bioinorg Chem Appl. 2006; 2006, 83131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsacheva, I.; Todorova, Z.; Momekova, D.; Momekov, G.; Koseva, N. Pharmacological Activities of Schiff Bases and Their Derivatives with Low and High Molecular Phosphonates. Pharmaceuticals. Basel 2023, 28;16(7), 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmatabadi, F.D.; Khojasteh, R.R.; Fard, H.K. New Cr, Mo, W, and Fe Metal Complexes with Potentially Heptadentate (S3N4) Tripodal Schiff Base Ligand: Synthesis, Characterization, and Antibacterial Activity. Russ J Gen Chem. 2020, 90, 1317–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parekh, J.; Inamdhar, P.; Nair, R.; Baluja, S.; Chanda S. J. Serb. Chem. Soc. 2005, vol. 70, p.1161. [CrossRef]

- Shukla, S.N.; Gaur, P.; Vaidya, P.; Chaurasia, B.; Jhariya, S. Biomimetic complexes of Mn(II), Fe(III), Co(II), and Ni(II) with 1,10-phenanthroline and a salen type ligand: tailored synthesis, characterization, DFT, enzyme kinetics, and antibacterial screening. Journal of Coordination Chemistry. 2018, 71:23, 3912-3933. [CrossRef]

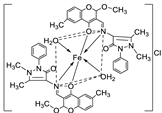

- Gehad, G.M.; Carmen, M.S. Metal complexes of Schiff base derived from sulphametrole and o-vanilin: Synthesis, spectral, thermal characterization and biological activity, Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy. 2007, Volume 66, Issues 4–5, Pages 949-958. [CrossRef]

- Gowda, K.R.S.; Naik, H.S.B.; Kumar, B.V.; Sudhamani, C.N.; Sudeep, H.V.; Naik, T.R.R.; Krishnamurthy, G. Synthesis, antimicrobial, DNA-binding and photonuclease studies of Cobalt(III) and Nickel(II) Schiff base complexes. Spectrochim. Acta Part A 2013, 105, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Dief, A.M.; Nassr, L.A.M.E. Tailoring, physicochemical characterization, anti-bacterial and DNA binding mode studies of Cu (II) Schiff bases amino acid bioactive agents incorporating 5-bromo-2-hydroxybenzaldehyde. J. Iran. Chem. Soc. 2015, 12, 943–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TWEEDY, B. Plant extracts with metal ions as potential antimicrobial agents. Phytopathology, 1964, 55 910-914.

- Karem, L.K.A.; Al-Noor, T.H. Mixed Ligand Complexes of Schiff Base and Nicotinamide: Synthesis, Characterization and Antimicrobial Activities. J. Phys.: Conf. 2020, Ser. 1660 012094. [CrossRef]

- Shukla, S.N.; Gaur, P.; Raidas, M.L.; Chaurasia, B.; Bagri, S.S. Novel NNO pincer type Schiff base ligand and its complexes of Fe(IIl), Co(II) and Ni(II): Synthesis, spectroscopic characterization, DFT, antibacterial and anticorrosion study. Journal of Molecular Structure. 2021, Vol. 1240, 130582, 0022-2860. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.; Khan, A.; Ikram, M.; Rehman, S.; Shah, M.; Un Nabi, H.; Ahuchaogu, A.A. Asian J. Chem. Sciences. 2017, 2, p. 2.

- Anacona, J.R.; Ruiz, K.; Loroño ,M.; Celis, F. Applied organometallic Chemistry. 2019. [CrossRef]

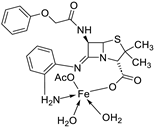

- Mumtaz, A.; Mahmud, T.; Elsegood, M.; Weaver, G.W. Synthesis, Characterization and in vitro Biological Evaluation of a New Schiff Base Derived from Drug and its Complexes with Transition Metal Ions. Revista de Chimie, 2019; 69, 1678–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Wasidi, A.S.; Naglah, A.M.; Al-Omar, M.A.; Al-Obaid, A-R.M.; Alosaimi, E.H.; El-Metwaly, N.M.; Refat, M.S.; Ahmed, A.S.; El-Deen, I.M.; Soliman, A.H.; Emam, A. Manganese (II), ferric (III), cobalt (II) and copper (II) thiosemicarbazone Schiff base complexes: Synthesis, spectroscopic, molecular docking and biological discussions. American Scientific Publishers. Materials Express, 2020, Vol. 10, No. 2, pp. 290-300(11). [CrossRef]

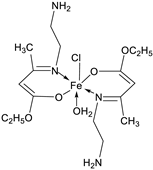

- Kumar, K.S, K. Aravindakshan, Synthesis, Characterization Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Studies of Complexes of Fe ( III ) , Ni ( II ) and Cu ( II ) with Novel Schiff Base Ligand ( E )-Ethyl 3-( ( 2-Aminoethyl ) Imino ) Butanoate. Journal of Pharmaceutical, Chemical and Biological Sciences. 2017.

- Mukhtar, H.; Sani, U.M.; Shettima, U.A. Synthesis, Physico-chemical and Antimicrobial Studies on Metal (II) Complexes with Schiff Base Derived from Salicylaldehyde and 2,4-Dinitrophenylhydrazine. International Research Journal of Pure and Applied Chemistry. 2019, n. pag. [CrossRef]

- Knittl, E.T.; Abou-Hussein, A.A.; Linert, W. Syntheses, characterization, and biological activity of novel mono- and binuclear transition metal complexes with a hydrazone Schiff base derived from a coumarin derivative and oxalyldihydrazine. Monatsh Chem. 2018, 149, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdullah, A.A.A. Biomedical applications of selective metal complexes of indole, benzimidazole, benzothiazole and benzoxazole: A review (From 2015 to 2022). Saudi Pharm J. 2023, 31(9), 101698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alosaimi, A.M.; Mannoubi, I.E.l.; Zabin, S.A. In Vitro Antimicrobial and in Vivo Molluscicidal Potentialities of Fe(III), Co(II) and Ni(II) Complexes Incorporating Symmetrical Tetradentate Schiff Bases (N2O2). Orient J Chem. 2020, 36(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priteshkumar, M.T.; Rajesh, J.P.; Ranjan, K.G.; Sunil, H.C.; Ankurkumar, J.K.; Yati, H.V.; Parth, T.; Anjali, B.T.; Jatin, D.P. ACS Omega 2023, 8(36), 33069–33082. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naureen, B.; Miana, G.A.; Shahid, K.; Asghar, M.; Tanveer, S.; Sarwar, A. Iron (III) and zinc (II) monodentate Schiff base metal complexes: Synthesis, characterisation and biological activities. Journal of Molecular Structure. 2021, Vol. 1231, 129946, 0022-2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

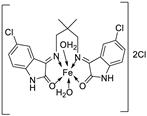

- Singh, N.P.; Kumar, K.; Kumar, A.; Agarwal, U. Synthesis, characterization and antimicrobial activity of Mn(II),Fe(II), Ni(II),Co(II) and Zn(II) complexes of schiff base derived from 2,2- Dimethylpropane 1, 3-Diamine and 5-Chloro isatin. Rasayan J. Chem. 2020, 13(1), 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borase, J.N.; Mahale, R.G.; Rajput, S.S.; Shirsath, D.S. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of heterocyclic methyl substituted pyridine Schiff base transition metal complexes. SN Appl. Sci. 2021, 3, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, S.Y.; Padole, N.S.; Wadekar, M.P.; Chaudhari, M.A. Synthesis, Spectroscopic and Antimicrobial Studies of Cu (II) and Fe (III) Complexes of Heterocyclic Schiff Base Ligand. Journal of Chemical and Pharmaceutical Research 2021, 13(9), 01–05. [Google Scholar]

- Close, P.S.; Subramaniam, L.; Mitu, J.; Narayan, D.S.A. Spectrochim Acta A. 2015, 134.

- Savcı, A.; Buldurun, K.; Kırkpantur, G. A new Schiff base containing 5-FU and its metal Complexes: Synthesis, Characterization, and biological activities. Inorganic Chemistry Communications. 2021, Vol. 134, 109060, 1387-7003. [CrossRef]

- Anacona, J.R.; Rodriguez, H. J Coord Chem. 2009, 62, p. 13.

- Kumar, G.; Devi, S.; Kumar, D. Synthesis of Schiff base 24-membered trivalent transition metal derivatives with their anti-inflammation and antimicrobial evaluation, Journal of Molecular Structure. 2016, Vol. 1108, pp 680-688, 0022-2860. [CrossRef]

- Elshafie, H.S.; Sadeek, S.A.; Camele, I.; Mohamed, A.A. Biological and Spectroscopic Investigations of New Tenoxicam and 1. 10-Phenthroline Metal Complexes. Molecules 2020, 25, 1027. [CrossRef]

- Sakr, S.H.; Elshafie, H.S.; Camele, I.; Sadeek, S.A. Synthesis, spectroscopic, and biological studies of mixed ligand complexes of 36emifloxacin and glycine with Zn (II), Sn (II), and Ce (III). Molecules. 2018, 23, 1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshafie, H.S.; Sadeek, S.A.; Camele, I.; Mohamed, A.A. Biochemical Characterization of New Gemifloxacin Schiff Base (GMFX-o-phdn) Metal Complexes and Evaluation of Their Antimicrobial Activity against Some Phyto- or Human Pathogens. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23(4):2110. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heaton, V.J.; Ambler, J.E.; Fisher, L.M. Potent Antipneumococcal Activity of Gemifloxacin Is Associated with Dual Targeting of Gyrase and Topoisomerase IV, an In Vivo Target Preference for Gyrase, and Enhanced Stabilization of Cleavable Complexes In Vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2000, 44, 3112–3117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

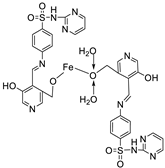

- Sultana, N.; Naz, A.; Arayne, M.S.; Mesaik, M.A. Synthesis, characterization, antibacterial, antifungal and immunomodulating activities of gatifloxacin–metal complexes J. Mol. Struct. 2010, 969, pp. 17-24.

- Ahmed, Y.M.; Omar, M.M.; Mohamed, G.G. Synthesis, spectroscopic characterization, and thermal studies of novel Schiff base complexes: theoretical simulation studies on coronavirus (COVID-19) using molecular docking. J IRAN CHEM SOC. 2022,19(3):901–19. [CrossRef]

- Sivaprakash, G.P.; Tharmaraj, M.; Jothibasu, A. Arun, antimicrobial analysis of schiff base ligands pyrazole and diketone metal complex against pathogenic organisms, Int J Adv Res. 2017, 5, 2656–2663. [CrossRef]

- Malik, M.A.; Dar, O.A.; Gull, P.; Wani, M.Y.; Hashmi, A.A. Heterocyclic Schiff base transition metal complexes in antimicrobial and anticancer chemotherapy, MedChemComm. 2018, 9, 409. [CrossRef]

- Gehad, G.; Mohamed, M.M. Omar, Yasmin M.A. Metal complexes of Tridentate Schiff base: Synthesis, Characterization, Biological Activity and Molecular Docking Studies with COVID-19 Protein Receptor, Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2021, 647, 2201–2218. [CrossRef]

- Hidayati, N.F.; Purwaningrum, W. Synthesis and characterization schiff base and complexes with Copper (II) and Iron (II) and their application as antibacterial agents. Journal of Physics: Conf. Series 1282. 2019 012074. [CrossRef]

- Kitouni, S.; Chafai, N.; Chafaa, S.; Houas, N.; Ghedjati, S.; Djenane, M. Journal of Molecular Structure 2023, 1281, 135083.

- Nevin, T.; Memet, Ş. Synthesis and Spectral Studies of Novel Co(II), Ni(II), Cu(II), Cd(II), and Fe(II).Metal Complexes with N-[5′-Amino-2,2′-bis(1,3,4-thiadiazole)-5-yl]-2-hydroxybenzaldehyde Imine (HL). Spectrosc Lett, 2009, 42:5, 258-267. [CrossRef]

- Ercan, B. Kinetic Properties of Peroxidase Enzyme from Chard (Beta vulgaris Subspecies cicla) Leaves. Int. J. Food Prop. 2013, 16:6, 1293-1303. [CrossRef]

- Turan, N.; Buldurun, K. Synthesis, characterization and antioxidant activity of Schiff base and its metal complexes with Fe(II), Mn(II), Zn(II), and Ru(II) ions: Catalytic activity of ruthenium(II) complex. Eur. J. Chem. 2018; 9(1), 22-29. [CrossRef]

- Said, M.A.; Al-unizi, A.; Al-Mamary, M.; Alzahrani, S.; Lentz, D. Easy coordinate geometry indexes, τ4 and τ5 and HSA study for unsymmetrical Pd(II), Fe(II), Zn(II), Mn(II), Cu(II) and VO(IV) complexes of a tetradentate ligand: Synthesis, characterization, properties, and antioxidant activities. Inorganica Chimica Acta. 2020; Vol. 505, 119434, 0020-1693. [CrossRef]

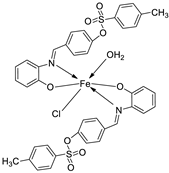

- Preeti, S.; Preeti, Y.; Kushneet, K.S.; Anurag, T.; Shilpika, B.M. Advancement in the synthesis of metal complexes with special emphasis on Schiff base ligands and their important biological aspects, Results in Chemistry. 2024, Volume 7, 101222. [CrossRef]

- Elkanzi, N.A.A.; Ali, A.M.; Hrichi1, H.; Abdou, A. New mononuclear Fe(III), Co(II), Ni(II), Cu(II), and Zn(II) complexes incorporating 4-{[(2 hydroxyphenyl) imino]methyl}phenyl-4-methylbenzenesulfonate (HL): Synthesis, characterization, theoretical, anti-inflammatory, and molecular docking investigation. Applied organometallic chemistry. 2022.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).