1. Introduction

Many countries implement a policy of income equalization for local budgets to foster the development of economically disadvantaged regions, territories, and communities. The transfer system is the primary mechanism of this state policy. The absence of state transfers leads to regional migration from poor regions to wealthy ones, resulting in a reduction of average labour productivity and production in poorer regions, and an overload in wealthier regions. Fiscal transfers between jurisdictions are substantial in many countries, particularly in developed ones.

The ability of the financial system to function effectively and continuously, supporting economic productivity can be considered financial stability (Schinasi 2005). A resilient financial system should have mechanisms to prevent the emergence of systemic financial problems that pose a threat to the economic system, which is the supersystem of the financial system. The public finance sphere is one of the defining components ensuring the stability of the financial system. Issues with budgetary balance can have a significant destabilizing impact on the financial system as a whole, as its resources will be directed toward addressing budgetary imbalances. The practical definition of the impact of state transfers on the stability of the financial system, in our opinion, involves addressing the question of whether this system moves towards the range of optimal (or close to optimal) financial indicators (metrics) with the growth of horizontal fiscal equalization or deviates from them.

The currently accepted conclusion that equalizing fiscal capacity is necessary, as it prevents inefficient migration to communities with high-income levels, was formulated by researchers (Buchanan 1950; Boadway and Frank 1982), as early as the 1950s of the past century. This forms the basis of the fiscal federalism concept. Research by Oates (1988) also notes a positive correlation between state spending on financing local public goods and the population size in communities.

However, the impact of state transfers on economic development is ambiguous. The advantages and disadvantages of equalization systems have been discussed by many economists, including Buchanan (1950) and Musgrave (1961). Many empirical studies have found statistically insignificant effects of state transfers on economic growth, while others have identified significant impacts, both positive and negative. In particular, studies such as Giambattista and Pennings (2017) and Oh and Reis (2012) demonstrate that targeted government transfers, through either the neoclassical wealth effect or the Keynesian aggregate demand effect, can lead to an increase in production levels in the national economy. Based on the example of the United State, the research by Hsieh and Moretti (2019) shows that irrational spatial allocation of productive forces, resulting from uneven income growth across regions, contributes to the overall economic growth reduction in the country.

The research by Henkel et al. (2018) demonstrates that the transfer system actually leads to smaller disparities between regions but at the cost of reducing the growth rate of the overall volume of national production. A meta-analysis conducted by Churchill and Yew (2017) confirms the widely held view in economic literature that increasing levels of government transfers result in a slowdown in economic growth. This is more pronounced in developed countries than in developing ones. Governments of many countries, including Canada, Germany, Australia, and Japan, use fiscal equalization through non-targeted state transfers to local budgets to equalize their income capacity, negatively affecting the formation of local fiscal potential (Albouy 2012). The research by Henkel et al. (2018) asserts that labour productivity in the state and GDP growth cannot be the indicators for evaluating the effectiveness of government transfers.

The goal of the policy of financial support for underdeveloped regions is to provide a boost to their economic development, which, in the long run, should be sustained by the region on its own. The impact of state transfers supporting less developed regions on macroeconomic stability and their long-term consequences is the subject of the work by Ehrlich and Seidel (2018). The experience of Germany, where, after the fall of the Iron Curtain and the reunification of West Germany and East Germany, the government stimulated the development of certain regions through substantial state transfers from 1971 to 1990, shows that, in the long term, the system of state transfers is inefficient as it insignificantly reduces the shift of economic activity to more developed regions. Transfers to regions with low real incomes may improve residents' welfare in the short term but they distort long-term incentives for labor migration to regions with the highest demand for labour (Albouy 2012).As a result, subsidies can worsen income disparities that they seek to eliminate through subsidies. Transfers stimulate the development of industrial agglomerations, which, unlike agricultural regions, continue after the cessation of transfers (Kline and Moretti 2014).

The mechanism of transfers often redistributes tax revenues from financially capable community budgets to poorer ones, allowing recipient municipalities to provide more public goods. Research on the impact of various types of EU transfers on the productivity, income, and transportation expenses of regions, conducted by Blouri and Ehrlich (2020), shows that, in general, the EU transfer system improves overall welfare. Significant improvement in overall welfare can be achieved through the redistribution of funds between regions, i.e., through the application of horizontal equalization.

In this context, the experience of Germany, whose fiscal federalism is based on interregional solidarity, is particularly interesting. The system of horizontal fiscal equalization of imbalances among the 16 federal states (Länderfinanzausgleich, LFA) contributes to the stability of Germany's financial system, as evidenced by Werner (2008). This study also shows that a significant level of equalization creates certain negative consequences, such as donor states losing incentives to increase tax revenues due to excessive resource extraction in favour of recipient states, while recipient states also lose incentives for development due to receiving resources without effort on their part.

However, it is challenging to separate the impact of the fiscal equalization system on financial stability from the impact of the tax distribution system between budgets. According to studies by Blöchliger et al. (2007), the delineation between tax distribution and intergovernmental transfers, which are two main (subcentral) financing mechanisms, is conditional. In addition, the problem is complicated by the lack of methods for adapting general scientific provisions to the conditions of specific economic situations (Shkvarchuk 2009).

Therefore, the impact of the mechanism of horizontal fiscal equalization on the stability of the financial system will be considered positive if the overall increase in the revenue capacity of local budgets participating in equalization is achieved without the systematic accumulation of national and/or local debt.

2. Materials and Methods

To assess the asymmetry of the equalization formula, we employ a quasi-experimental strategy to analyze potential scenarios of the impact of the horizontal fiscal equalization system on the stability of public finances. For this purpose, we consider basic and reverse grants, which are the main type of regional transfers for horizontal equalizing the revenue capacity of budgets of municipalities (the basic level of the budgetary system of Ukraine).

The formula for horizontal equalization of the fiscal capacity of local budgets in Ukraine involves the calculation of the fiscal capacity index of the local budget , which depends on the level of per capita tax revenue. The calculation takes into account the population and the number of registered internally displaced persons. Local budgets with a fiscal capacity index below 0.9 of the average indicator for Ukraine (excluding the indicators of the budgets of the city of Kyiv and local budgets in temporarily occupied territories) receive a basic grant to increase their budgetary provision. Local budgets with a fiscal capacity index above 1.1 transfer a portion of their budgetary resources to support less capable municipalities. In this case, horizontal equalization for the budgets of municipalities is carried out only in terms of personal income tax (PIT) (Budget Code of Ukraine 2010).

The basis for determining the impact of the mechanism for equalizing horizontal fiscal imbalances is the equalization model:

where

– the fiscal capacity index of the i-th municipality;

– tax revenue to the budget of the i-th municipality in the reporting year;

– the population of the i-th community (municipality), including internally displaced persons, at the beginning of the year for which the grant is calculated;

i – municipality;

n – the number of municipalities.

If – no equalization is performed.

If – the budget of the i-th municipality provides a reverse grant.

If – the budget of the i-th municipality receives a basic grant.

The reverse grant (

) of the i-th municipality per year is calculated by the formula:

Gross reverse grant .

The basic grant (

) for the i-th municipality per year is calculated by the formula:

Gross base grant .

We calculate basic and reverse grants for 1439 municipalities (in total, there are 1469 municipalities in Ukraine, with 30 located in temporarily occupied territories, so information for calculations on them is unavailable). Then we conduct counterfactual experiments, where we change the calculation subject, the number of budgets in the calculation, and the calculation period. Under different scenarios of calculation, we determine whether the equalization mechanism has positive or negative affect on the stability of the public finance system based on the criterion of not accumulating budgetary debt.

In the first calculation option, we compute reverse and basic grants for municipalities in 2022, as well as gross reverse and gross basic grants based on the current calculation methodology using official data on tax revenues to local budgets (Open budget 2023) and official population data for communities (Ministry of Finance of Ukraine 2023). Scenario 1 assumes that the grant calculation for 2022 is based on tax revenue data for 2021 (Open budget 2023), not for 2020 as stipulated by the current official methodology. Scenario 2 involves including the budget of Kyiv in the horizontal equalization system; scenario 3 includes the budget of Kyiv in the equalization system, with calculations based on 2021 data. Scenario 4 involves equalizing revenue capacity based on the receipts of two taxes (1) personal income tax (PIT) and (2) the unified tax, using 2021 data (Open budget 2023). Scenario 5 entails equalizing revenue capacity based on the receipts of two taxes—(1) PIT and (2) the unified tax—while including the budget of Kyiv in the equalization system, with calculations based on 2021 data.

In scenarios 4 and 5, horizontal equalization for municipality budgets is conducted separately for personal income tax (PIT) and the unified tax. In this case, the amount of received basic subsidy or paid reverse subsidy is determined as follows:

If

, then

If

, then

We demonstrate that the timeliness of input data for calculation affects the result; including all distribution subjects in the allocation changes the result; and changing the calculation subject for equalization alters the outcome. Comparing the calculation results across scenarios with actual data allows us to provide quantitative answers to questions about improving the equalization mechanism to enhance the stability of public finances. The goal is to promote preventive and timely corrective policies to avoid financial instability.

3. Results

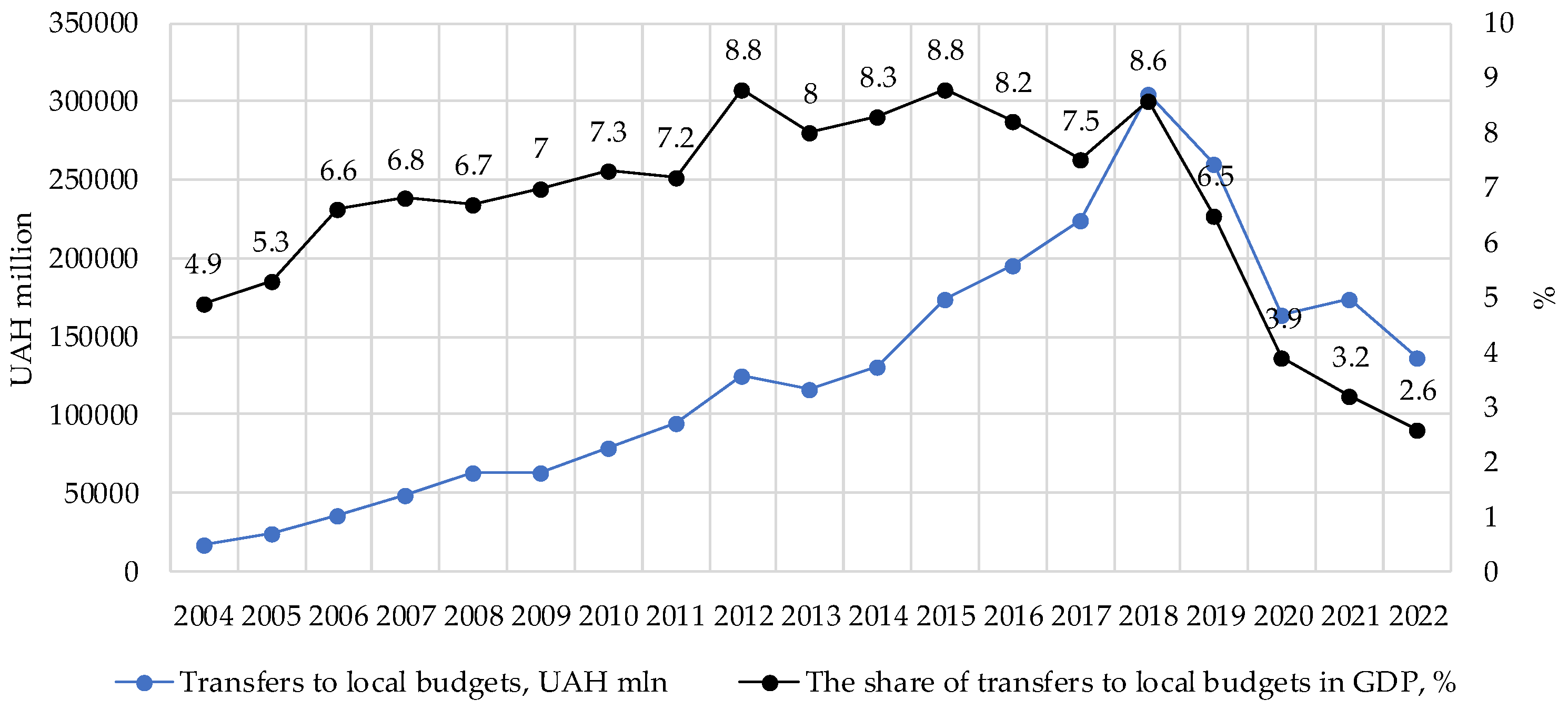

Until 2015, the main transfer to local budgets in Ukraine from the state budget was an equalization grant, which was allocated to support the financial capacity of local budgets to exercise their delegated expenditure powers, mainly in the social sphere, and was provided without specifying the directions of its use. The equalization grant served as a form of state regulation for equalization "by expenditure," and its relative weight in the structure of transfers was nearly 50%. At the same time, 95% of local budgets received the equalization grant. The level of gross transfers from the state budget to local budgets increased annually and reached 8.8% of GDP (

Figure 1). Such a significant level of gross transfers became burdensome for the state budget, increasing the level of national debt, negatively impacting the stability of the public finance system. Moreover, the equalization system "by expenditure" for many years led to the accumulation of funds at the level of large cities – regional centers, and reduced the availability of public goods for residents of small towns and settlements, making it unjust and inefficient, stimulating urbanization and migration processes.

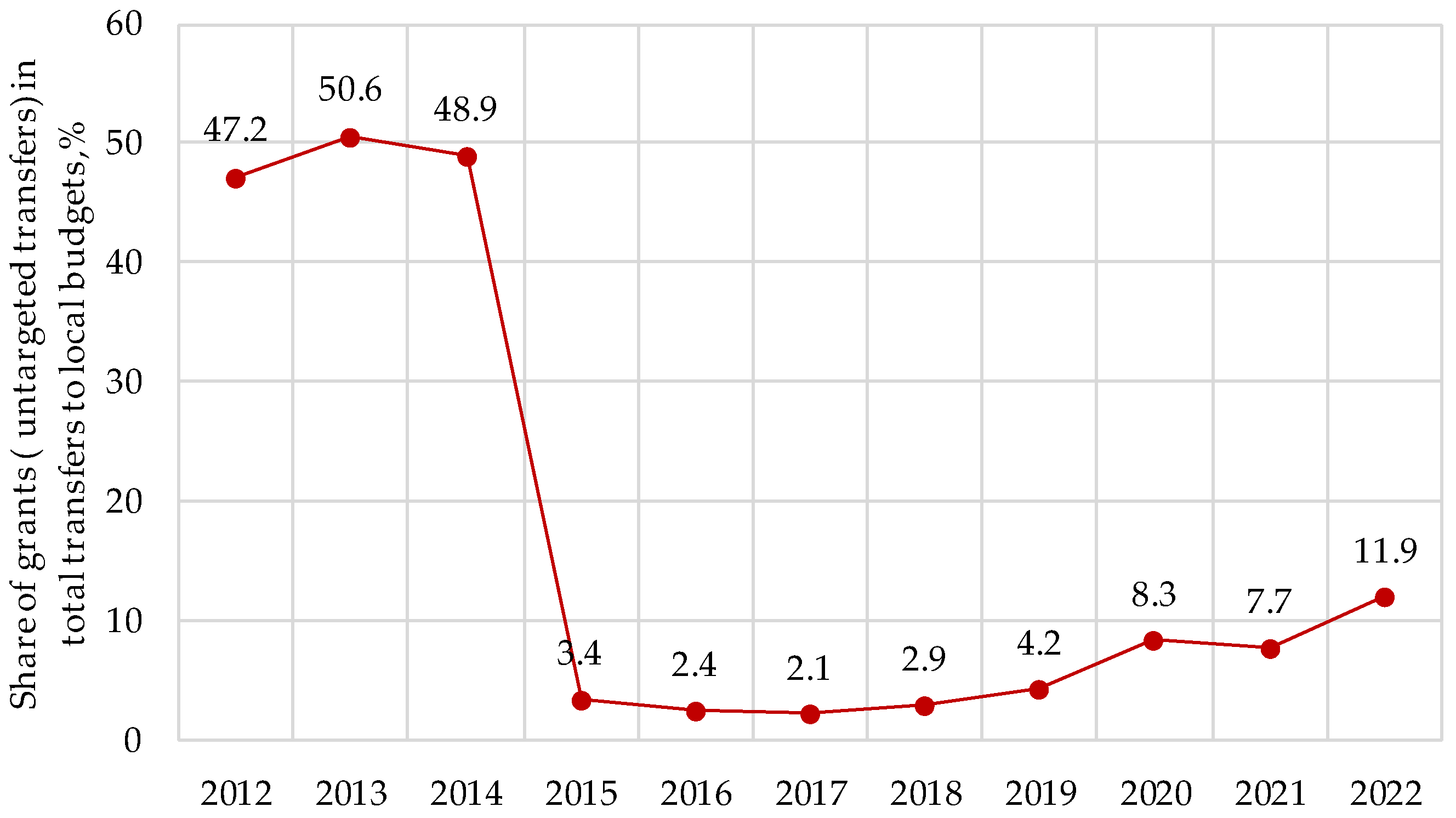

The decentralization reform of 2015-2020 envisages the creation of conditions for regional development by forming 1469 municipalities through the consolidation (amalgamation) of budgets of over 11,000 small settlements, assigning a larger percentage of nationwide taxes to them, and delegating a larger volume of expenditure responsibilities to them to address the majority of issues locally. The system of state transfers was also reformed: the equalization of vertical fiscal imbalances (arising from the mismatch of financial resources of the local budget with the volume of delegated expenditure powers for the provision of social services) is carried out by providing target transfers from the state budget to local budgets – subventions; equalization of horizontal fiscal imbalances (arising from differences in the tax potential of administrative-territorial units due to objective economic, historical, natural, geographic, and other development features) is carried out by providing local budgets with non-targeted transfers – grants. To strengthen the financial base of local budgets, the regulation system for horizontal fiscal imbalances was changed from equalization by expenditure to equalization by revenue, resulting in a significant decrease in the share of grants (

Figure 2), and an increase in subventions, accordingly.

The decentralization reform also foresees a transition from 2015 to equalizing horizontal fiscal imbalances exclusively through solidarity grants: the amount withdrawn from "rich" local budgets in the form of reverse grants should correspond to the amount of grants to "poor" communities by providing them with a basic grant. In this case, the state budget, from which the reverse grant is withdrawn and to which the basic grant is transferred, should only act as an intermediary. The gross volume of transfers has been constantly decreasing since 2018 (

Figure 1) due to a reduction in the volume of subventions. Instead, the volume of grants is growing (

Figure 2), both in absolute and relative terms. The number of recipient municipalities of the subsidy is significant – in 2022, 1071 municipalities receive the basic grant, which constitutes 75% of their total number.

Before the start of the decentralization reform, the reverse grant covered only 3% of the financial support needs of financially incapable municipalities, and in 2022, it covers 66%, which is interpreted as a positive result of the decentralization reform and a shift in the fiscal imbalance equalization system towards improving the stability of public finances. In other words, the improvement of public finance stability occurs because the redistribution of funds increasingly takes place at the municipality level, and the need is less satisfied with the funds of the state budget.

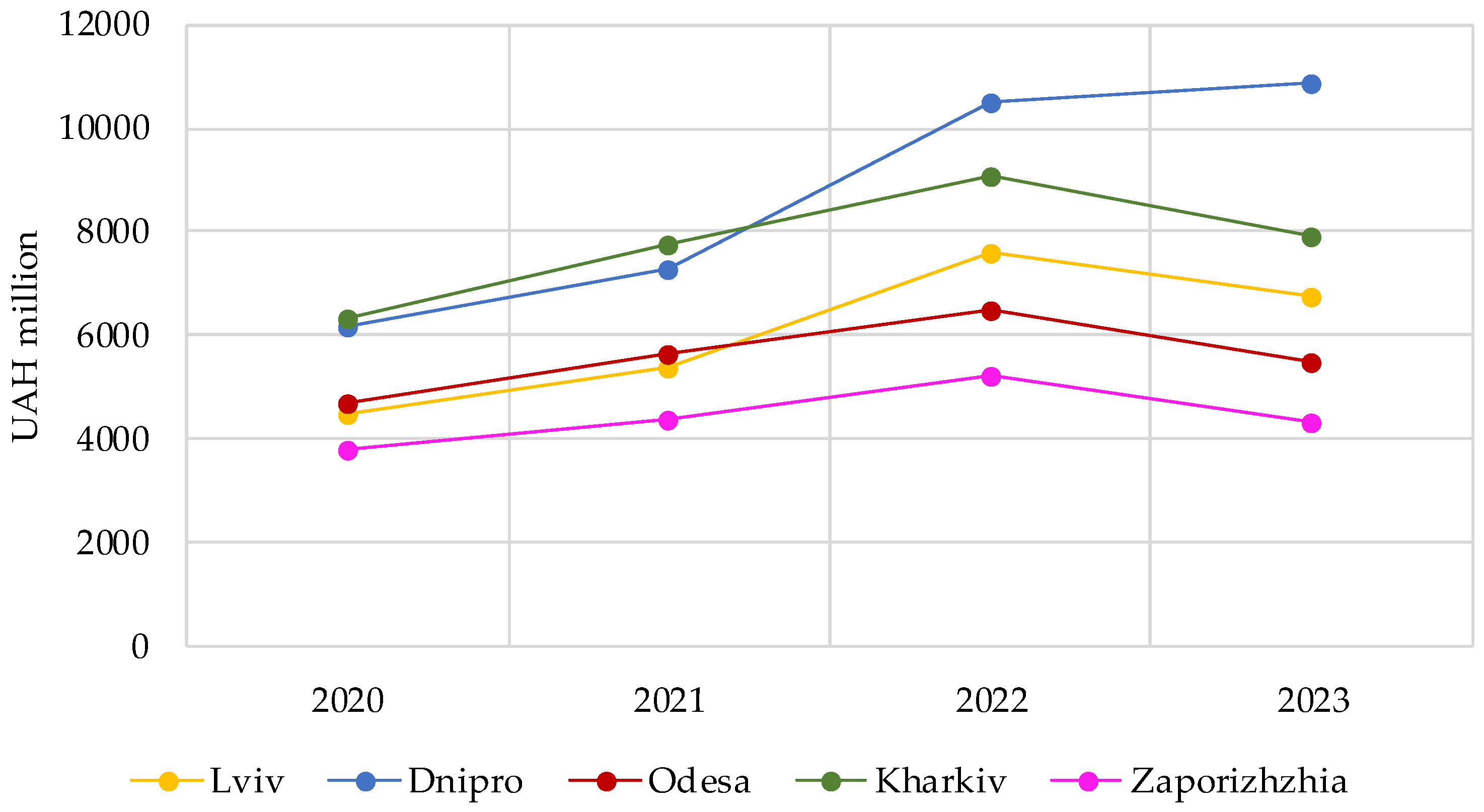

However, according to the current methodology for calculating the equalization grant, the calculation of the average level of personal income tax (PIT) receipts per capita is based on data on the actual PIT receipts to the budget not for the reporting year but for the year preceding the reporting year. In other words, the calculation of the grant is based on indicators with a time lag of 2 years, which are somewhat outdated and do not reflect the real trend since the annual growth rate of PIT receipts in municipalities ranges from 14 to 45% (

Figure 3).

The calculation of reverse and basic grants for 2022 based on actual data on PIT receipts in 2021 (Scenario 1), rather than in 2020, as calculated by the Ministry of Finance, shows that the gap between gross reverse and basic grants will significantly increase. In particular, the amount of reverse grant will increase by 17%, while the basic grant will increase by 243% (

Table 1), resulting in the basic grant covering only 22.5% with the reverse grant. Accordingly, the amount of shortfall of over 77% would have to be covered from the state budget, increasing the burden on the state budget and demonstrating the real and much lower stability of public finances.

Such significant changes in the growth rates of reverse and basic grants arise from substantial differences in the growth rates of PIT receipts to the budgets of municipalities (

Figure 3), the reasons for which require separate investigation. Differences in the growth rates of PIT receipts to the budgets of municipalities contribute to changes in the ranking of donor municipalities based on their contribution to the structure of gross reverse grants (

Table 2).

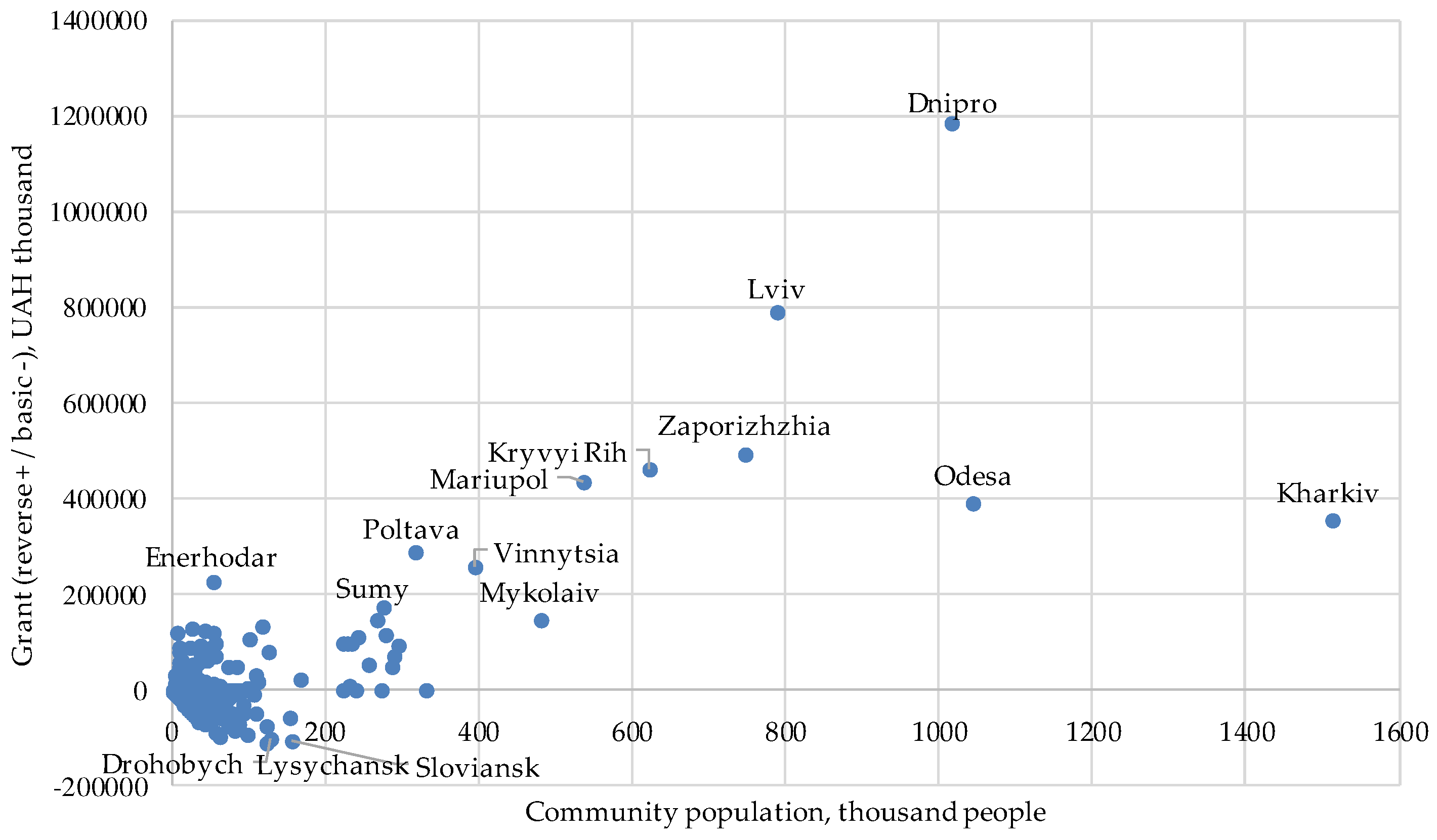

Due to the presence of a corresponding resource base – industrial potential, highly qualified personnel, developed institutions, and a comparatively better demographic situation – the largest financial resources traditionally accumulate in the budgets of regional centers, which, after the local elections of 2020, became urban territorial communities and currently are the largest donors of reverse grants. In 2022, reverse grants were transferred to the state budget by 207 municipalities, which constitutes 15% of their total number (

Figure 4), Moreover, 45% of all paid reverse grants are attributed to the top 10 "donor" cities: Dnipro (12.4%), Lviv (8.2%), Zaporizhzhia (5.1%), Kryvyi Rih (4.8%), Odesa (4.1%), Kharkiv (3.7%), Poltava (3%), Vinnytsia (2.7%), as well as Mariupol and Energodar (

Table 2;

Figure 4), imposing significant burdens on them and serving as a disincentive.

Moreover, the municipality with the highest fiscal capacity – the city of Kyiv, the capital of Ukraine – is excluded from the system of horizontal equalization. The exclusion of Kyiv from the equalization formula leads to an increase in the burden on donors of reverse grants and on the state budget. It should be noted that before the decentralization reform in 2015, the budget of Kyiv was involved in the equalization system along with all other local budgets.

The inflow of personal income tax (PIT) into the budget of Kyiv significantly exceeds the PIT revenues of other municipalities (by 4 times or more). This is due to both (1) the significant number of taxpayers – legal entities registered in Kyiv (over 20% of the total number of taxpayers - legal entities) and (2) the inclusion of PIT from the labour income of employees of large enterprises (Naftogaz Ukraine, Ukrposhta, Ukrzaliznytsia, etc.) in the budget of Kyiv. In Ukraine, contrary to Article 9 of the European Charter of Local Self-Government, the PIT paid by a tax agent - a legal entity (its branch, division, other separate unit) or a representative office of a non-resident legal entity is credited to the respective budget based on the location of the tax agent, rather than the place of residence (registration) of the individual taxpayer (Budget Code of Ukraine 2010). As a result, the PIT from the income of residents of all communities – employees of large enterprises working throughout the country but registered in Kyiv – is credited to the budget of Kyiv. Meanwhile, social services for citizens who are employees of large state enterprises registered in Kyiv are provided at the expense of the budget of the municipality where they reside, not at the expense of the Kyiv budget. Such a distribution system exacerbates the already significant development disparities between the capital and the regions, violates the principles of unity and fairness of Ukraine's budgetary system stipulated in Article 7 of the Budget Code (Budget Code of Ukraine 2010), and leads to a reduction in the stability of public finances. Since the revenues of the Kyiv budget are offered only to those who live within Kyiv, they also create inefficient incentives. The amount of transfers to local budgets, calculated without taking into account all subsidy donors, is significantly lower and insufficient. The chronic deficiency of local budgets is covered by local borrowings, leading to an increase in local debt and a general decrease in the stability of public finances.

The inclusion of the largest donor – the budget of the city of Kyiv – into the equalization formula will allow to reduce the burden on other donors of reverse grant, as demonstrated in

Table 1, where the calculation of grant amounts is carried out both according to the government scheme (scenario 2) and with updated data on tax revenues for 2021 (scenario 3). In this case, if reverse and basic grants for 2022 are calculated according to scenario 2, the need for a basic grant will be covered by a reverse grant at 62.7%. That is, the burden on the state budget will not significantly increase, and the system of equalizing fiscal imbalances will correspond to the criteria of fairness and completeness, in accordance with the principles of budgetary system construction, as outlined in the Budget Code of Ukraine (Budget Code of Ukraine 2010). At the same time, the growth rate of the gross basic grant (38%) will exceed the growth rate of the reverse grant (32%), indicating a movement of the equalization system towards further reducing the stability of the public finance system.

The calculation of reverse and basic grants for 2022, taking into account the largest donor and based on data on PIT receipts in 2021 (scenario 3), shows that the need for basic grants will be covered by reverse grants at 28.3%, which is a slightly better result (2.3%) than the implementation of scenario 1. In this case, the gross reverse grant will increase by 61%, while the gross basic grant will increase by 28%. Thus, the implementation of scenario 3 will reduce the asymmetry of the equalization formula, significantly increase the resources of incapable municipalities (by more than 8 times), and reduce the burden on donor municipalities (

Table 2).

In scientific literature, it is considered that the prospects for the financial and economic development of large territorial communities are greater than those of small ones. In particular, a significant portion of Ukraine's territorial communities (60%) with a basic grant exceeding 20% of their own revenues have a population of less than 7,000 people. However, the analysis results show that the largest amounts of the basic grant are received by municipalities with a population of over 100,000 people – Lysychansk, Drohobych, Slovyansk (

Figure 4), which formally, based on PIT receipts alone, are considered "poor". Moreover, the average indicator of own revenue per person in the budgets of these municipalities is slightly lower than the average similar indicator for all of Ukraine. This raises doubts about the correctness of defining the recipients of the grant. Among the own revenues of local budgets in Ukraine, the second-largest, after PIT (over 50%), in terms of receipts there is the unified tax (over 11%). The unified tax is the main entrepreneurial tax for small business entities, whose development the state stimulates by introducing a simplified system of accounting, reporting, and taxation for them. In Ukraine, the unified tax is classified as a local tax, and its receipts are credited to local budgets. The taxation with the unified tax involves dividing taxpayers into four groups, each with different tax rates and bases. The unified tax replaces the payment of PIT and profit income tax and essentially is not a local tax since local self-government authorities do not set the tax rate for taxpayers in the third group, who constitute over 50% of all taxpayers of this tax. Therefore, they have no influence on the receipts of over 83% of the unified tax amount (State Tax Service of Ukraine 2023). The rapid increase in the receipts of the unified tax to local budgets largely arises from the artificial fragmentation of large and medium-sized business entities for the purpose of tax optimization (Yaroshevych et al. 2019). Therefore, the unified tax, which is a significant source of receipts to local budgets, can also be considered the basis for equalizing the fiscal capacity of municipalities.

As a result of calculating reverse and basic grants based on the equalization of horizontal fiscal imbalances separately for PIT and separately for the unified tax, using data on the receipts of these taxes in 2021 (scenario 4), the need for a basic grant will be covered by a reverse grant at 26%. However, in this case, the gross volume of reverse grants will increase by 27.5%, while the basic grant will increase by 10%. In the case of involving the largest donor in the system of horizontal equalization of fiscal capacity based on two taxes (scenario 5), the gross volume of reverse grants will increase by 105%, while the basic grant will increase by 44%. In this case, the need for a basic grant will be covered by a reverse grant at 32.1%, and thus, 67.9% of the gross need for basic grants will be covered by funds from the state budget. In the case of applying scenario 4 and scenario 5, there will be a significant increase in the amounts of funds distributed among recipient budgets (by 8.2 and 9.8 times, respectively); the burden on donor municipalities will decrease, and 56.8% of the gross volume of reverse grants will be covered by the largest donor – the budget of Kyiv (

Table 2).

4. Discussion

The calculation of reverse and basic grants based on outdated data on PIT receipts to municipality budgets understates the volume of the gross basic subvention for recipient municipalities. It also understates the amounts of compensatory payments from the state budget to cover the difference between the gross reverse grant and the need for the gross basic grant, artificially inflating the indicators of the success of the fiscal equalization reform and distorting the overall picture of public finance stability.

The excess of the growth rates of the gross basic grant over the growth rates of the gross reverse grant (scenario 1), with a significant gap between the gross reverse and basic grants (34% under the current calculation system and 77.5% in our calculations), indicates that the existing equalization system is moving towards further imbalance, increase of the gap, and reduction of the financial stability of the public finance system.

The exclusion of the community with the highest tax potential from the equalization system artificially increases the fiscal capacity of all other communities, thereby reducing the volumes of the basic grant for grant recipients. This, in turn, diminishes their ability to provide public services guaranteed by the state without resorting to debt financing. The increase in the volumes of debt financing for grant recipient municipalities leads to a decrease in the stability of public finances due to the growth of local debt. Calculations of gross reverse and basic grants under scenario 3 and scenario 5, which involve the inclusion of the largest donor in the equalization system, show that despite the low current coverage level of the gross reverse grant for the needs of the gross basic grant (28.3% and 32.1%, respectively), the growth rates of the gross reverse grant will exceed the growth rates of the gross basic grant. This gives grounds to assert that the equalization of horizontal fiscal imbalances will move towards establishing equality between the gross reverse and basic grants, thereby ensuring the stability of the public finance system in the state's financial system.

Exceeding the growth rates of the gross reverse grant over the gross basic grant is proposed to be considered an indicator of the equalization system's movement towards improving the stability of the financial system. Changing the subject of calculating the fiscal capacity of municipalities, i.e., considering other fiscal revenues of municipalities (scenario 4 and scenario 5), will positively influence the movement of the equalization system towards strengthening the stability of the financial system, as evidenced by the excess growth rates of the reverse grant over the growth rates of the basic grant.

5. Conclusions

According to the criteria used here, the equalization policy in Ukraine appears quite ineffective and socially unjust. The current equalization system exacerbates the unevenness of socio-economic development in the regions of Ukraine, leading to different possibilities for funding local budget expenditures and reducing the financial stability of public finances.

The mechanism for calculating the fiscal capacity of developing municipalities, which underlies horizontal financial equalization, needs improvement in the approach to determining the calculation subject: (1) considering all municipalities, i.e., including Kyiv in the equalization; (2) considering other tax revenues of local budgets in addition to PIT; (3) conducting calculations based on data on tax receipts for the reporting year when planning grants in budgets.

It would also be advisable to implement EU legal norms into Ukrainian legislation, in accordance with the ratified Charter of Local Self-Government by Ukraine, and credit PIT to the local budget based on the place of residence of the taxpayer. In this case, the structure of PIT receipts, as well as the structure of donors and grant recipients, may change significantly. Huge disparities in the parameters of formed communities, including population size (from 7,000 in one community to 1.5 million in another), require an investigation into the possibilities of smoothing out the unevenness of municipality potential by further aggregating some of them. Therefore, Ukraine's horizontal equalization system requires further reform.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Nataliia Yaroshevych and Iryna Kondrat; methodology, Nataliia Yaroshevych; formal analysis, Nataliia Yaroshevyc.; validation, Nataliia Yaroshevych, Iryna Kondrat and Tetyana Kalaitan; investigation, Iryna Kondrat; resources, Iryna Kondrat; data curation, Iryna Kondrat and Tetyana Kalaitan; writing—original draft preparation, Nataliia Yaroshevych and Iryna Kondrat; writing—review and editing, Iryna Kondrat and Tetyana Kalaitan; visualization, Nataliia Yaroshevych; supervision, Iryna Kondrat; project administration, Tetyana Kalaitan. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data generated during the study are presented in this publication only. The calculations were based on official data from the Ministry of Finance of Ukraine.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- (Albouy 2012) Albouy, D. 2012. Evaluating the efficiency and equity of federal fiscal equalization. Journal of Public Economics 96: 824-839. [CrossRef]

- (Blöchliger et al. 2007) Blöchliger, H., Merk, O., Charbit, C., and Mizell. L. 2007. Fiscal equalisation in OECD countries. Working Paper 4. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- (Blouri and Ehrlich 2020) Blouri, Y. M., and Ehrlich, M. 2020. On the optimal design of place-based policies: A structural evaluation of EU regional transfers. Journal of International Economics 125: 103319. [CrossRef]

- (Boadway and Frank 1982) Boadway, R., and Frank, F. 1982. Equalization in a Federal State: an Economic Analysis. Economic Council of Canada : Ottawa. ISBN 066-011-131-4.

- (Buchanan 1950) Buchanan, J. 1950. Federalism and Fiscal Equity. American Economic Review 40: 583-99.

- (Budget Code of Ukraine 2010) Budget Code of Ukraine. 2010. Available online: https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/2456-17#Text (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- (Churchill 2017) Churchill, A. S., and Yew, S. L. 2017. Are government transfers harmful to economic growth? A meta-analysis. Economic Modelling 64: 270-287. [CrossRef]

- (Ehrlich and Seidel 2018) Ehrlich, M., and Seidel, T. 2018. The persistence effects of place-based policies. Evidence from the West-German Zonenrandgebiet. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 10: 344-74. [CrossRef]

- (Giambattista and Pennings 2017) Giambattista, E., and Pennings, S. 2017. When is the Government Transfer Multiplier Large? European Economic Review 100: 525-543. [CrossRef]

- (Henkel et al. 2018) Henkel, M., Seidel, T., and Suedekum, J. 2018. Fiscal transfers in the spatial economy. Discussion Paper №322. Edited by Normann, H.-T. Düsseldorf: Düsseldorf Institute for Competition Economics. Available online: https://d-nb.info/1204591490/34 (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- (Hsieh and Moretti 2019) Hsieh, C.-T., and Moretti, E. 2019. Housing constraints and spatial misallocation. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 11: 1-39. [CrossRef]

- (Kline and Moretti 2014) Kline, P., and Moretti, E. 2014. Local economic development, agglomeration economies and the big push: 100 years of evidence from the Tennessee Valley Authority. Quarterly Journal of Economics 129: 275-331. [CrossRef]

- (Ministry of Finance of Ukraine 2023) Ministry of Finance of Ukraine. Population by cities of Ukraine as of January 1, 2022. Available online: https://index.minfin.com.ua/ua/reference/people/town/ (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- (Musgrave 1961) Musgrave, R. A. 1961. Approaches to a Fiscal Theory of Political Federalism. New York: National Bureau of Economic Research, pp. 97-134. ISBN: 0-87014-303-4.

- (Oates 1988) Oates, W. E. 1988. On the measurement of congestion in the provision of local public goods. Journal of Urban Economics 24: 85-94. [CrossRef]

- (Oh and Reis 2012) Oh, H., and Reis, R. 2012. Targeted transfers and the fiscal response to the great recession. Journal of Monetary Economics 59: S50-S64. [CrossRef]

- (Open budget 2023) Open budget. Vebsait – State budget web portal of the Ministry of Finance of Ukraine for citizens. Available online: https://openbudget.gov.ua/local-budget?id=26000000000 (accessed on 22 December 2023).

- (Schinasi 2005) Schinasi, G. J. 2005. Safeguarding financial stability: theory and practice. Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund 2005. pp. 98-103. ISBN 978-158-906-440-9. Available online: https://www.elibrary.imf.org/display/book/9781589064409/ch006.xml (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- (Shkvarchuk 2009). Shkvarchuk, L. O. 2009. Futures contracts within system of enterprise cash flow management. Actual Problems of Economics 11: 221–228.

- (State Tax Service of Ukraine 2023) State Tax Service of Ukraine. Since the beginning of 2023, entrepreneurs have paid UAH 15.2 billion in single tax to the budget. Available online: https://tax.gov.ua/media-tsentr/novini/685975.html (accessed on 12 December 2023).

- (Werner 2008) Werner, J. 2008. Fiscal Equalisation among the states in Germany. Working Papers 02-2008. Langen: Institute of Local Public Finance. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/5164384 (accessed on 22 December 2023).

- (Yaroshevych et al. 2019) Yaroshevych, N. B., Cherkasova, S. V., and Kalaitan, T. V. 2019. Inconsistencies of small business fiscal stimulation in Ukraine. Journal of Tax Reform 5: 204-219. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).