Submitted:

03 January 2024

Posted:

04 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

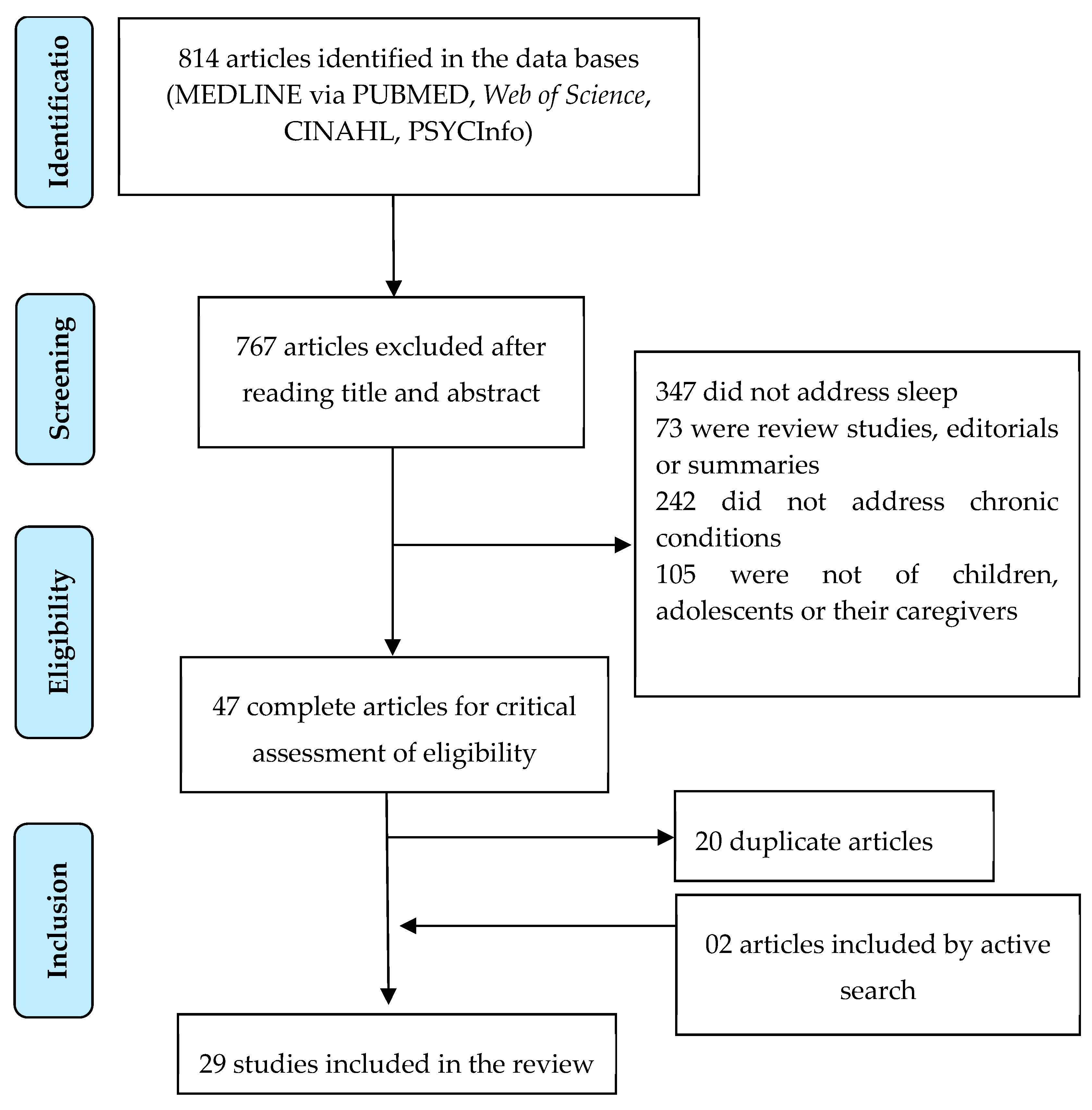

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Category 1: major alterations in the sleep patterns of children and adolescents with chronic conditions

3.2. Category 2: the relationship between sleep disorders and other symptoms in children and adolescents with chronic conditions

3.3. Category 3: impaired sleep patterns of families of children and adolescents with chronic conditions

3.4. Category 4: sleep alterations and their relationship to other problems in families of children and adolescents with chronic conditions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Associação Americana de Pediatria. Enfermedades crónicas. HealthyChildren.org. 2017. Available online: https://www.healthychildren.org/Spanish/health-issues/conditions/chronic/Paginas/default.aspx (accessed on 27 December 2023).

- Andrade, R.S. de; Santos, R. dos S.F.V. dos; Santos, A.E.V. dos; Andrade, N.L. de; Macedo, I.F. de; Nunes, M.D.R. Instrumentos para avaliação do padrão de sono em crianças com doenças crônicas: revisão integrativa. Revista Enfermagem UERJ 2018, 26, 31924. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Narendran, G.; Tomfohr-Madsen, L.; Schulte, F. A systematic review of sleep in hospitalized pediatric cancer patients. Psychooncology 2017, 26, 1059–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murillo, R.; Lambiase, M.J.; Rockette-Wagner, B.J.; Kriska, A.M.; Haibach, J.P.; Thurston, R.C. Racial/Ethnic differences in the associations between physical activity and sleep duration: a population-based study. J Phys Act Health 2017, 14, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amorim, J.R.; Silva, I.A.; Shimizu, I.S. Avaliação da qualidade de sono em pacientes com câncer de mama em quimioterapia. Revista Brasileira de Mastologia 2017, 27, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setoyama, A.; Ikeda, M.; Kamibeppu, K. Objective Assessment of Sleep Status and Its Correlates in Hospitalized Children with Cancer: Exploratory Study. Pediatr Int 2016, 58, 842–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sateia, M.J. International Classification of Sleep Disorders-Third Edition. Chest 2014, 146, 1387–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniel, L.; Kazak, A.E.; Li, Y.; Hobbie, W.; Ginsberg, J.; Butler, E.; Schwartz, L. Relationship between sleep problems and psychological outcomes in adolescent and young adult cancer survivors and controls. Support Care Cancer 2016, 24, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahrami, N.; Pahlavanzadeh, S.; Marofi, M. Effect of a supportive training program on anxiety in children with chronic kidney problems and their mothers’ caregiver burden. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res 2019, 24, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whittemore, R.; Knafl, K. The Integrative Review: Updated Methodology. Journal of advanced nursing 2005, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, K.D.S.; Silveira, R.C. de C.P.; Galvão, C.M. Revisão integrativa: método de pesquisa para a incorporação de evidências na saúde e na enfermagem. Texto contexto - enferm 2008, 17, 758–764. [CrossRef]

- The Joanna Briggs Institute (Org.). Reviewers’ Manual-Methodology for JBI Mixed Methods Systematic Reviews. 2014. Available online: http://joannabriggs.org/assets/docs/sumari/ReviewersManual_Mixed-Methods-Review-Methods-2014-ch1.pdf (accessed on 27 December 2023).

- Morgenthaler, T.; Alessi, C.; Friedman, L.; Owens, J.; Kapur, V.; Boehlecke, B.; Brown, T.; Chesson, A., Jr.; Coleman, J.; Lee-Chiong, T.; et al. Practice Parameters for the Use of Actigraphy in the Assessment of Sleep and Sleep Disorders: An Update for 2007. Sleep 2007, 30, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, H.M. Scientific Guidelines for Conducting Integrative Research Reviews Author ( s ). Review of Educational Research 1982, 52, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnyk, B.M.; Fineout-Overholt, E. Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing & Healthcare: A Guide to Best Practice; Edição: 4.; Wolters Kluwer Health, 2018.

- Edelstein, O.E.; Shorer, T.; Shorer, Z.; Bachner, Y.G. Correlates of quality of life in mothers of children with diagnosed epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2019, 93, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunes, M.D.R.; Nascimento, L.C.; Fernandes, A.M.; Batalha, L.; De Campos, C.; Gonçalves, A.; Leite, A.C.A.B.; de Andrade Alvarenga, W.; de Lima, R.A.G.; Jacob, E. Pain, sleep patterns and health-related quality of life in paediatric patients with cancer. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2019, 28, e13029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rensen, N.; Steur, L.M.H.; Schepers, S.A.; Merks, J.H.M.; Moll, A.C.; Grootenhuis, M.A.; Kaspers, G.J.L.; van Litsenburg, R.R.L. Concurrence of Sleep Problems and Distress: Prevalence and Determinants in Parents of Children with Cancer. European Journal of Psychotraumatology 2019, 10, 1639312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stabouli, S.; Gidaris, D.; Printza, N.; Dotis, J.; Papadimitriou, E.; Chrysaidou, K.; Papachristou, F.; Zafeiriou, D. Sleep Disorders and Executive Function in Children and Adolescents with Chronic Kidney Disease. Sleep Medicine 2019, 55, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, K.D.; Kuhn, B.R.; DeHaai, K.A.; Wallace, D.P. Evaluation of a behavioral treatment package to reduce sleep problems in children with Angelman Syndrome. Research in Developmental Disabilities 2013, 34, 676–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bromberg, M.H.; Gil, K.M.; Schanberg, L.E. Daily Sleep Quality and Mood as Predictors of Pain in Children with Juvenile Polyarticular Arthritis. Health Psychology 2011, 31, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byars, K.C.; Chini, B.; Hente, E.; Amin, R.; Boat, T. Sleep disturbance and sleep insufficiency in primary caregivers and their children with cystic fibrosis. Journal of Cystic Fibrosis 2020, 19, 777–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, L.C.; Walsh, C.M.; Meltzer, L.J.; Barakat, L.P.; Kloss, J.D. The Relationship between Child and Caregiver Sleep in Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Maintenance. Support Care Cancer 2018, 26, 1123–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, I.D.; Greenbaum, L.A.; Gipson, D.; Wu, L.L.; Sinha, R.; Matsuda-Abedini, M.; Emancipator, J.L.; Lane, J.C.; Hodgkins, K.; Nailescu, C.; et al. Prevalence of Sleep Disturbances in Children and Adolescents with Chronic Kidney Disease. Pediatr Nephrol 2012, 27, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kieckhefer, G.M.; Lentz, M.J.; Tsai, S.-Y.; Ward, T.M. Parent-Child Agreement in Report of Nighttime Respiratory Symptoms and Sleep Disruptions and Quality. Journal of Pediatric Health Care 2009, 23, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, S.R.; Boergers, J.; Kopel, S.J.; McQuaid, E.L.; Seifer, R.; LeBourgeois, M.; Klein, R.B.; Esteban, C.A.; Fritz, G.K.; Koinis-Mitchell, D. Sleep Hygiene and Sleep Outcomes in a Sample of Urban Children With and Without Asthma. Journal of Pediatric Psychology 2017, 42, 825–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meltzer, L.J.; Booster, G.D. Sleep Disturbance in Caregivers of Children With Respiratory and Atopic Disease. Journal of Pediatric Psychology 2016, 41, 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roumelioti, M.-E.; Wentz, A.; Schneider, M.F.; Gerson, A.C.; Hooper, S.; Benfield, M.; Warady, B.A.; Furth, S.L.; Unruh, M.L. Sleep and Fatigue Symptoms in Children and Adolescents With CKD: A Cross-Sectional Analysis From the Chronic Kidney Disease in Children (CKiD) Study. Am J Kidney Dis 2010, 55, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, S.-Y.; Labyak, S.E.; Richardson, L.P.; Lentz, M.J.; Brandt, P.A.; Ward, T.M.; Landis, C.A. Brief Report: Actigraphic Sleep and Daytime Naps in Adolescent Girls with Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain. Journal of Pediatric Psychology 2008, 33, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, A.J.; Johnson, K.P.; Miaskowski, C.; Lee, K.A.; Gedaly-Duff, V. Sleep Quality and Sleep Hygiene Behaviors of Adolescents during Chemotherapy. J Clin Sleep Med 2010, 6, 439–444, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2952746/. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waxmonsky, J.G.; Mayes, S.D.; Calhoun, S.L.; Fernandez-Mendoza, J.; Waschbusch, D.A.; Bendixsen, B.H.; Bixler, E.O. The Association between Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder Symptoms and Sleep Problems in Children with and without ADHD. Sleep Med 2017, 37, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, M.D.R.; Jacob, E.; Adlard, K.; Secola, R.; Nascimento, L. Fatigue and Sleep Experiences at Home in Children and Adolescents With Cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 2015, 42, 498–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hysing, M.; Sivertsen, B.; Stormark, K.M.; Elgen, I.; Lundervold, A.J. Sleep in Children with Chronic Illness, and the Relation to Emotional and Behavioral Problems—A Population-Based Study. Journal of Pediatric Psychology 2009, 34, 665–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macaulay, G.C.; Boucher, S.E.; Yogarajah, A.; Galland, B.C.; Wheeler, B.J. Sleep and Night-Time Caregiving in Parents of Children and Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus – A Qualitative Study. Behavioral Sleep Medicine 2020, 18, 622–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozyurt, G.; Bayram, E.; Karaoglu, P.; Kurul, S.H.; Yis, U. Quality of Life and Sleep in Children Diagnosed with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy and Their Mothers’ Level of Anxiety: A Case-Control Study. Dusunen Adam The Journal of Psychiatry and Neurological Sciences 2015, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridolo, E.; Caffarelli, C.; Olivieri, E.; Montagni, M.; Incorvaia, C.; Baiardini, I.; Canonica, G.W. Quality of Sleep in Allergic Children and Their Parents. Allergologia et Immunopathologia 2015, 43, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, O.; Sogut, A.; Gulle, S.; Can, D.; Ertan, P.; Yuksel, H. Sleep Quality and Depression-Anxiety in Mothers of Children with Two Chronic Respiratory Diseases: Asthma and Cystic Fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros 2008, 7, 495–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuksel, H.; Sogut, A.; Yilmaz, O.; Demet, M.; Ergin, D.; Kirmaz, C. Evaluation of Sleep Quality and Anxiety-Depression Parameters in Asthmatic Children and Their Mothers. Respir Med 2007, 101, 2550–2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Yang, L.; Liu, S.; Ma, S.; Wang, Y.; Cai, Z.; Du, H.; Li, R.; Kang, L.; Su, M.; et al. Survey of Insomnia and Related Social Psychological Factors Among Medical Staff Involved in the 2019 Novel Coronavirus Disease Outbreak. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feeley, C.A.; Turner-Henson, A.; Christian, B.J.; Avis, K.T.; Heaton, K.; Lozano, D.; Su, X. Sleep Quality, Stress, Caregiver Burden, and Quality Of Life in Maternal Caregivers of Young Children With Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia. Journal of Pediatric Nursing 2014, 29, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keilty, K.; Cohen, E.; Spalding, K.; Pullenayegum, E.; Stremler, R. Sleep Disturbance in Family Caregivers of Children Who Depend on Medical Technology. Arch Dis Child 2018, 103, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardar-Yagli, N.; Saglam, M.; Inal-Ince, D.; Calik-Kutukcu, E.; Arikan, H.; Savci, S.; Ozcelik, U.; Kiper, N. Hospitalization of Children with Cystic Fibrosis Adversely Affects Mothers’ Physical Activity, Sleep Quality, and Psychological Status. J Child Fam Stud 2017, 26, 800–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Estrela, C.; Barker, E.T.; Lantagne, S.; Gouin, J.-P. Chronic Parenting Stress and Mood Reactivity: The Role of Sleep Quality. Stress and Health 2018, 34, 296–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nozoe, K.T.; Hachul, H.; Hirotsu, C.; Polesel, D.N.; Moreira, G.A.; Tufik, S.; Andersen, M.L. The Relationship Between Sexual Function and Quality of Sleep in Caregiving Mothers of Sons with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Sexual Medicine 2014, 2, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nozoe, K.T.; Polesel, D.N.; Moreira, G.A.; Pires, G.N.; Akamine, R.T.; Tufik, S.; Andersen, M.L. Sleep Quality of Mother-Caregivers of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Patients. Sleep Breath 2016, 20, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buysse, D.J.; Reynolds, C.F.; Monk, T.H.; Berman, S.R.; Kupfer, D.J. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A New Instrument for Psychiatric Practice and Research. Psychiatry Research 1989, 28, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertolazi, A.N.; Fagondes, S.C.; Hoff, L.S.; Dartora, E.G.; da Silva Miozzo, I.C.; de Barba, M.E.F.; Menna Barreto, S.S. Validation of the Brazilian Portuguese Version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. Sleep Medicine 2011, 12, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szymanski, J.S. Aktivitaet Und Ruhe Bei Den Menschen. Z Angew Psychol 1922, 20, 192–222, https://publikationen.ub.uni-frankfurt.de/frontdoor/index/index/year/2009/docId/11635. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeh, A.; Acebo, C. The Role of Actigraphy in Sleep Medicine. Sleep Med Rev 2002, 6, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telles, S.C.L.; Corrêa, É.A.; Caversan, B.L.; Mattos, J. de M.; Alves, R.S.C. O Significado Clínico da Actigrafia. Revista Neurociências 2011, 19, 153–161. [CrossRef]

- Chronic Kidney Disease in Children Study. About the CKiD Cohort Study 2003. Available online: https://statepi.jhsph.edu/ckid/welcome/about/ (accessed on 27 December 2023).

- Owens, J.A.; Spirito, A.; McGUINN, M.; Nobile, C. Sleep Habits and Sleep Disturbance in Elementary School-Aged Children. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics 2000, 21, 27–36, https://journals.lww.com/jrnldbp/Abstract/2000/02000/Sleep_Habits_and_Sleep_Disturbance_in_Elementary.5.aspx. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.G.; Silva, C.R.; Braga, L.B.; Serrão Neto, A. Questionário de Hábitos de Sono das Crianças em Português - validação e comparação transcultural. J. Pediatr. (Rio J.) 2014, 90, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBourgeois, M.K.; Giannotti, F.; Cortesi, F.; Wolfson, A.R.; Harsh, J. The Relationship Between Reported Sleep Quality and Sleep Hygiene in Italian and American Adolescents. Pediatrics 2005, 115, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns, M.W. A New Method for Measuring Daytime Sleepiness: The Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep 1991, 14, 540–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertolazi, A.N.; Fagondes, S.C.; Pedro, L.S.H.; Barreto, S.S.M.; Johns, M.W. Validação da escala de sonolência de Epworth em português para uso no Brasil. J Bras Pneumol 2009, 35, 877–883, https://www.jornaldepneumologia.com.br/details/636/pt-BR/validacao-da-escala-de-sonolencia-de-epworth-em-portugues-para-uso-no-brasil. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chervin, R.D.; Hedger, K.; Dillon, J.E.; Pituch, K.J. Pediatric Sleep Questionnaire (PSQ): Validity and Reliability of Scales for Sleep-Disordered Breathing, Snoring, Sleepiness, and Behavioral Problems. Sleep Medicine 2000, 1, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruni, O.; Ottaviano, S.; Guidetti, V.; Romoli, M.; Innocenzi, M.; Cortesi, F.; Giannotti, F. The Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children (SDSC). Construction and Validation of an Instrument to Evaluate Sleep Disturbances in Childhood and Adolescence. J Sleep Res 1996, 5, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harsh, J.; Easley, A.; LeBourgeois, M.K. A Measure of Children’s Sleep Hygiene. Sleep, 2002; 25, A316–A317, https://aquila.usm.edu/fac_pubs/3620. [Google Scholar]

- Hale, L.; Berger, L.M.; LeBourgeois, M.K.; Brooks-Gunn, J. Social and Demographic Predictors of Preschoolers’ Bedtime Routines. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2009, 30, 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, C.M. Insomnia: Psychological Assessment and Management; Insomnia: Psychological assessment and management; Guilford Press: New York, NY, US, 1993; pp. xvii, 238; ISBN 978-0-89862-210-2.

- Castro, L. de S. Adaptação e Validação Do Índice de Gravidade de Insânia (IGI): Caracterização Populacional, Valores Normativos e Aspectos Associados. Universidade Federal de São Paulo (UNIFESP) 2011, 103.

- Vecchi, C.R. Causes and Effects of Lack of Sleep in Hospitalized Children. Arch Argent Pediat 2020, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neves, G.S.M.L.; Giorelli, A.S.; Florido, P.; Gomes, M. da M. Transtornos do sono: visão geral. Rev. bras. neurol 2013, 49, 57–71, http://files.bvs.br/upload/S/0101-8469/2013/v49n2/a3749.pdf.

- Anggerainy, S.W.; Wanda, D.; Nurhaeni, N. Music Therapy and Story Telling: Nursing Interventions to Improve Sleep in Hospitalized Children. Comprehensive Child and Adolescent Nursing 2019, 42, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sociedade Portuguesa do Sono Recomendações SPS e SPP: prática da sesta da criança nas creches e infantários, públicos ou privados. Available online: https://www.spp.pt/UserFiles/file/Noticias_2017/VERSAO%20PROFISSIONAIS%20DE%20SAUDE_RECOMENDACOES%20SPS-SPP%20SESTA%20NA%20CRIANCA.pdf (accessed on 27 December 2023).

- Nunes, M.L.; Bruni, O. Insomnia in childhood and adolescence: clinical aspects, diagnosis, and therapeutic approach. Jornal de Pediatria (Versão em Português) 2015, 91, S26–S35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stickland, A.; Clayton, E.; Sankey, R.; Hill, C.M. A Qualitative Study of Sleep Quality in Children and Their Resident Parents When in Hospital. Arch Dis Child 2016, 101, 546–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz, J.C.; Milbrath, V.M.; Gabatzm, R.I.B.; Krug, F.R.; Hirschmann, B.; Oliveira, M.M. de Cuidado à família da criança com doença crônica. Rev. enferm. UFPE on line 2018, 1397–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| INSTRUMENT | YEAR/COUNTRY OF ORIGIN | APPLICATION |

|---|---|---|

| Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) | 1989/USA [46] | The instrument, comprising 19 questions relating to sleep quality and disturbance in the prior month, evaluates subjective quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, sleep efficiency, sleep disorders, use of medication and daytime dysfunction. The questions are graded into scores from zero (no difficulty) to three (severe difficulty) and the sum total ranges from zero to 21, where the greater the value, the worse the sleep quality [46,47] |

| Wrist Actigraphy | 1922/Germany [48]. | The wrist actigraph is a device in the form of a wristwatch with the ability to store data over a specified time period. The system’s scoring programme can calculate sleep efficiency and duration. The device is based on an acceleration sensor, which converts external factors, which produce motion and influence Circadian rhythm, into measurements. The numerical representation is aggregated into a constant time interval, generally called a period (for example, one minute) [49,50]. |

| CKiD Symptoms List | 2003/USA and Canada [51] | Chronic Kidney Disease in Children (CKiD) is a, prospective, observational study of children and adolescents with mild and moderate renal insufficiency. It produced a list of symptoms to be filled out for the prior month, indicating the number of days when the participant felt each of them, as well as describing the severity with which each symptom was experienced [51]. In the study selected for this review, participants responded with regard to the symptoms: “weakness”, “early waking”, “falling asleep during the day” and “diminished alertness” [28]. |

| Abbreviated Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ) | 2000/ USA [52] | This screening instrument answered by parents comprises 33 common items of child behaviour, grouped into three domains: Dyssomnias, Parassomnias and Respiratory Sleep Disturbances. The “long version” (48 items) includes other questions. Responses are scored on a three-point Likert scale (rarely = 0-1 night per week; sometimes = 2-4 nights per week; generally = 5-7 nights per week). Scores of 41 or more indicate possible sleep disorders [52,53]. |

| Adolescent Sleep-Wake Scale (ASWS) | 2005/Italy and USA [54] | This was developed as a children’s sleep-wake scale and is applied to adolescents from 12 to 18 years old. It comprises 28 items, divided into five dimensions of behaviour – going to bed, falling asleep, maintaining sleep, reinitiating sleep and returning to wakefulness – and using a six-point scale (“always”, “often, if not always”, “often”, “sometimes”, “now and then” and “never"). The higher the score, the better the sleep quality [54]. |

| Adolescent Sleep Hygiene Scale | 2005/Italy and USA [54]. | This is an adaptation of the Children’s Sleep Hygiene Scale, applicable to adolescents from 12 to 18 years old. It contains 28 items that assess issues that facilitate and hinder sleep, which are divided into nine domains: physiological, cognitive, emotional, sound environment, daytime sleep, substances, sleep routine, sleep stability and room/bed sharing. On a six-point scale (“always”, “often, if not always”, “quite often”, “sometimes”, “now and then” and "never"), the higher the score, the better the sleep hygiene behaviour [54]. |

| Epworth Sleepiness Scale | 1991/Australia [55] | This self-applied questionnaire assesses the likelihood of falling asleep (never, slight chance, moderate chance and high chance) in eight activities of daily living: sitting and reading; watching TV; sitting, inactive, in a public place; as a passenger in a car for an hour or more without stopping for a break; lying down to rest when circumstances permit; sitting and talking to someone; sitting quietly after a meal without alcohol; and in a car, while stopped for a few minutes in traffic or at a light. Total scores range from 0 to 24. A score of more than 10 suggests a diagnosis of excessive daytime sleepiness [55,56]. |

| Paediatric Sleep Questionnaire | 2000/USA [57] | Comprises around 20 items, which can be answered in about 5 minutes. The questionnaire, which evaluates symptoms of sleep disorders in children, includes scales for obstructive respiratory sleep-related disorders (mouth breathing, night sweats, nocturia, enuresis, nasal congestion, sleep bruxism, retarded growth, obesity), snoring, daytime sleepiness, insomnia and restless leg syndrome. Scores above 0.33 are considered to suggest a diagnosis of sleep-related disorder [57] |

| Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children | 1996/Italy [58] | Consists of a 26-item sleep evaluation instrument applicable to children from 3 to 18 years old. It assesses disorders of initiating and maintaining sleep, sleep breathing, arousal, sleep-wake transition, excessive daytime sleepiness and sleep hyperhidrosis. It uses a Likert-type scale scoring from 26 to 130. A score of 39 was established as the cut-off point suggestive of sleep disorders [58] |

| Children’s Sleep Hygiene Scale (CSHS) | 2002/USA [59] | This examines children’s sleep hygiene as reported by parents. It consists of 22 items that assess physiological, cognitive, emotional, environmental, sleep routine and sleep stability issues associated with sleep hygiene. Responses are on a six-point Likert scale range from Never to Always, with higher scores indicating better sleep hygiene [59] |

| General Sleep Inventory | 2009/USA [60] (Hale et al., 2009) | This scale uses parent-report data to assess whether the child: has a regular bedtime and, if so, at what time, and whether the family has enforced that bedtime in the prior five nights; whether the family has one or more sleep routines and, if so, whether the family has involved itself in those routines in the prior five nights. It also evaluates indicators of sleep routines: interaction with parents, non-interaction with parents, watching television or video, eating a snack and hygiene-related behaviour. It uses a six-point Likert scale from Never to Always [60]. The study selected for this review also evaluated whether the children shared a room, shared a bed, slept in their own bed, or in another room and how often they were disturbed by domestic and/or neighbourhood noise, as well as how many people lived in the domicile [26]. |

| Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) | 1993/USA [61] | This instrument evaluates patients’ perception of their insomnia. There are three versions: patient (self-report), third-party (spouse, for example) and doctor. It consists of seven items that assess: severity of difficulty initiating and maintaining sleep, early morning waking, satisfaction with the sleep pattern, interference in daytime functioning, perception of impairment attributed to sleep problem and degree of distress or concern caused by the sleep problem. Responses are on a scale of 0 to 4 points and the total ranges from 0 to 28. The higher the score, the more suggestive of severe insomnia [61,62]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).