1. Introduction

Around 1% of all women are positive for anti-Ro (anti-Sjögren´s syndrome related antigen A/SSA)[

1,

2,

3]. For women with a known rheumatic disease, the prevalence is around 40% for patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and in patients with Sjögren Syndrome it may be as high as 100%[

2,

4]. Due to the Fcγ receptor associated transplacental transport of anti-Ro (anti SSA) and anti-La (anti SSB) antibodies, fetuses are at risk of transient and permanent organ damage. The most severe manifestations are irreversible complete congenital heart block (CHB) and dilated cardiomyopathy. Around 1-2% of fetuses of antibody positive primigravid mothers or multipara without a previously affected off-spring are affected[

5,

6]. Other cardiac manifestation can be valve dysfunction, sinus bradycardia and endocard fibroelastosis (EFE)[

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. Conduction system and myocardial disease can lead to fetal or neonatal death and a lifelong need for cardiac pacing or even heart transplantation[

11]. Mortality rate rises with diagnosis at a gestational age < 20 weeks, ventricular rate < 50 bpm, fetal hydrops and impaired left ventricular function[

12]. Recurrence rate of fetal CHB in mothers with a previously affected fetus is around 16%-18%[

7,

8,

11,

13]. Hydroxychloroqine (HCQ) reduces the recurrence of CHB in anti-SSA/Ro exposed pregnancies by more than 50% and is recommended as secondary prophylaxis[

14]. Anti-Ro/anti-La antibodies start crossing the placenta in the late first trimester[

15]. They bind to their corresponding antigens on cardiac cells that have undergone apoptosis, a process which translocates the otherwise intracellularly positioned Ro and La antigens to the cell surface. These immune-complex bearing cardiomyocytes are then phagocytosed by macrophages. Downstream signaling generates the production of pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrosing cytokines[

11,

16,

17]. Another theory is that antibodies cross-react with L-type calcium channels (LTCC)[

2,

18]. The histological correlate of CHB is antibody-mediated inflammation and fibrosis of the AV node[

7,

15,

19]. Once a complete CHB has developed, the condition is irreversible and potentially not any more amenable to anti-inflammatory treatment. There appears to be a “window of opportunity” in the transition to complete CHB in which anti-inflammatory therapy (IVIG and fluorinated steroids) can consolidate the status quo, namely 2dn degree CHB, or even restore sinus rhythm[

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. Even though, there is consensus that cardiac affections in neonatal lupus is a potentially life threatening condition, there is no consensus on prenatal treatment[

28].

It was previously assumed that the development of a CHB was a slow developing and measurable continuum from prolongation of AV conduction time to complete CHB and the approach of surveillance by weekly echocardiography measuring the AV conduction time was based on this idea. In contrast to this assumption, Jaeggi et al. and others could show, that fetal AV prolongation does not reliably predict progressive heart block[

29,

30]. It is unclear whether first degree heart block detected in utero also progresses to more advanced heart block[

2]. Transition time from incomplete CHB to irreversible CHB can occur in hours[

24,

25,

27].

Surveillance of women at risk is controversial and there is no clear consensus how to monitor these pregnancies[

31,

32]. Intense surveillance by weekly echocardiography is frequently recommended between (16) 18-26 weeks GA[

15,

19,

26,

29,

33]. Considering that complete CHB can develop in hours, the time interval for potentially successful intervention is short and will be missed by this approach. The event rate is only 1-2%, so, weekly examinations will overtreat most pregnant women at risk, is not cost-effective and cannot successfully prevent development of complete CHB.

To perform surveillance of at-risk pregnancies more individually and precisely, efforts have been made to find additional predictors of risk and guide surveillance of these women based on their individual risk profile. Quantification of antibodies and definition of a specific risk cut-off seems to be a promising approach[

34,

35,

36]. In order to timely detect emerging complete CHB, more frequent controls of the fetal heart rate by a hand-held Doppler seems to be a promising option[

19,

25].

In Germany, home monitoring by hand-held doppler is not yet offered as a routine in monitoring these high-risk pregnancies. A universal applied guideline does not exist.

Our study has two objectives:

To determine the status quo for the surveillance, prevention, and treatment of pregnant women with anti-Ro/La antibodies and their fetuses by ultrasound specialists in Germany and their willingness to offer home monitoring in their patients.

To evaluate the requirements and practicability of home monitoring at a single university center in Germany.

2. Materials and Methods

Part 1: We conducted a quantitative cross-sectional study. The data was collected prospectively using an online questionnaire between March 6, 2023, to March 31, 2023.

The internet link was sent by the "German Society for Ultrasound in Medicine" (DEGUM) to its members by email. The survey was performed via the online platform "LamaPoll" and was addressed at ultrasound specialists with DEGUM level I-III who take care of pregnant women with anti-Ro/SSA and/or anti-La/SSB antibodies. DEGUM has different levels of expertise with level I, being the most basic and level III the most expert level. In Germany it is common practice that the care of these women is not provided by pediatric cardiologists, but by specialists of prenatal diagnosis and fetal therapy.

Participation was completely anonymous. Persons without DEGUM level and those who do not manage anti-Ro/SSA and/or anti-La/SSB antibody-positive pregnant women were excluded.

Part 2: To evaluate the feasibility of home monitoring by hand-held doppler, we initiated a prospective single-center study of anti-Ro/SSA and/or anti-La/SSB-positive pregnant women, which were recruited from January 2021 to December 2023. The patients were recruited from the department of prenatal diagnosis and fetal therapy of the University Hospital Giessen and Marburg (UKGM) in Germany. The study was approved by the ethics committee of Justus-Liebig University, Gießen, Germany, AZ 225/21 and Philipps University, Marburg, Germany, AZ 77/22.

Inclusion criteria:

- -

Pregnant women with singleton pregnancies and known rheumatic disease in whom anti-Ro/SSA and/or anti La/SSB antibodies have been detected.

- -

Gestational age between 16-26 weeks.

- -

Age ≥ 18 years

Exclusion criteria:

- -

Pregnant women with known rheumatic disease, without evidence of anti-Ro/SSA and/or anti La/SSB antibodies

- -

Gestational age ≥ 26 weeks

- -

Multi-fetal pregnancies

- -

Fetal conduction system disease already present in the current pregnancy

- -

Decline to sign the consent form

Initial visit:

Patients with a known rheumatic disease and confirmed antibody positivity were offered study participation. After extensive counselling, patients were included if they have signed the study consent form.

Blood samples were analyzed in our department of clinical immunology for the presence of anti-SS-A/SS-B antibodies in a pooled approach (ENA pool) using a standardised ELISA method (Euroimmun, Lübeck, Germany). Samples with a result above the decision limit are examined for the specific presence of anti-Ro50/Ro62 antibodies in a standardized chemiluminescence method (Werfen, Barcelona, Spain).

A detailed medical history was taken, using an independently designed medical history form, which included questions on their demographics, rhematic disease, current medication, and previous pregnancies (

supplementary material 2).

At initial visit, a detailed ultrasound including fetal echocardiography to evaluate the cardiac anatomy, rhythm, and function were obtained in all cases. Fetal echocardiography was done by an expert in fetal medicine (R.A-F, I.B., A.W. and J.S.). Fetal heart rate was determined from measures of consecutive Doppler waveforms of the umbilical artery. AV interval, defined as the time between the onsets of atrial and ventricular contraction was measured from the onset of the mitral a wave to onset of aortic outflow from simultaneous mitral and aortic outflow Doppler wave forms.

To be sure that at the moment of immediate need the therapy will be covered by the insurance company, an application for potential cost coverage for off-label IVIG therapy was faxed to the patient´s health insurance company at the moment of study inclusion.

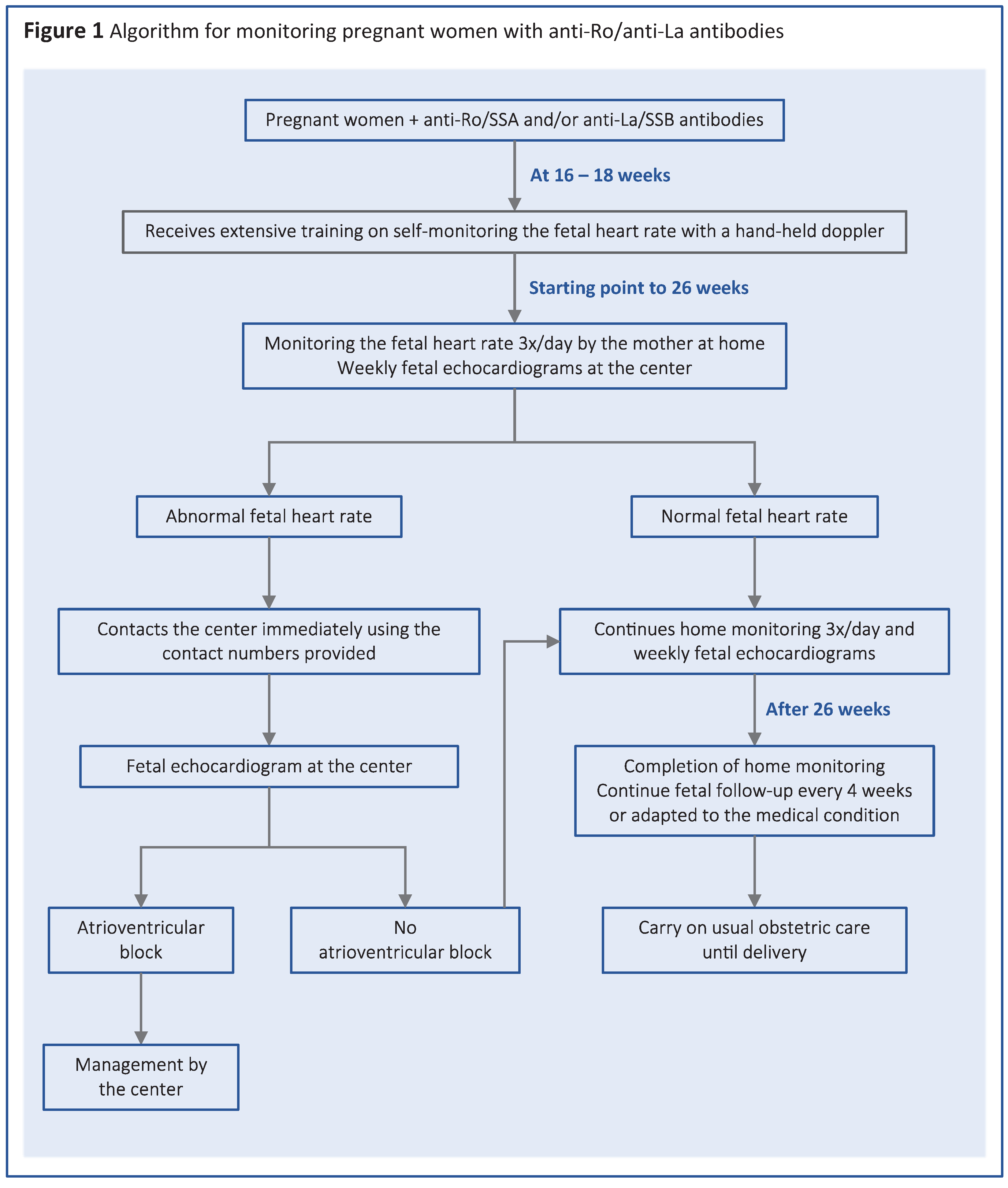

The patients received extensive training on self-monitoring using a hand-held doppler device at 16 weeks gestational age. In case of a previously affected child, women were instructed to start homemonitoring from the 16th week of pregnancy, while women who had not given birth to an affected child began homemonitoring at 18 weeks. More specifically, the mothers were instructed to measure the fetal heart rate three times a day by hand doppler and give feedback. They were requested to document the fetal heart rate in a weekly documentation sheet, which was checked at each follow-up appointment at the study center.

In this sheet patients could also indicate on a scaled question, how they felt about homemonitoring. The scale ranged between “I fully agree” to “I do not agree at all”(

supplementary material 3).

To distinguish a regular rhythm from an irregular rhythm, the women were shown videos and audio recordings of normal and abnormal fetal heart rates. In case that fetal rhythm was abnormal, or fetal heart rate was below 100 bpm, the patients were instructed to present at our center within 6 hours to confirm or exclude abnormal heart rhythm and get anti-inflammatory treatment within 12 hours.

The documentation forms contained a table for documenting the measurements for the period of one week, as well as questions as to whether the women felt strengthened or stressed by the measurements. At each subsequent visit, mothers reviewed results of the previous week(s) of monitoring. Any contacts with the center were documented.

After 26th weeks of gestation home monitoring by the mothers was completed. Thereafter, controls at our center were scheduled in accordance with the disease status, but normally every 4 weeks.

After birth, the infants were seen by our neonatologists and received cardiac evaluation, including electrocardiogram, by a pediatric cardiologist (Figure 1).

All data were de-identified and entered a local database. Statistical analysis was performed using Excel spreadsheet mathematic functions (Version 16.69.1), using mean values, minimum and maximum.

3. Results

3.1. Web based survey

3.1.1. Setting and qualification

A total of 114 ultrasound specialists with DEGUM level I-III took part in our online survey. Six with DEGUM Level I, 99 with DEGUM Level II and 7 Level III and 1 participant did not give any details and was excluded from analysis. 56.6% of the specialists work in an outpatient setting, the remaining 43.4% work in a hospital setting. 57.7% , work with a laboratory that gives a quantitative or semiquantitative analysis of anti-Ro/La antibodies. 9 % do just get positive or neative results without further quantification and 33.3% stated that they did not know. Over 80% of participants treat 1-5 women at risk per year, 14% treat 6 or more.

3.2. Prevention and treatment

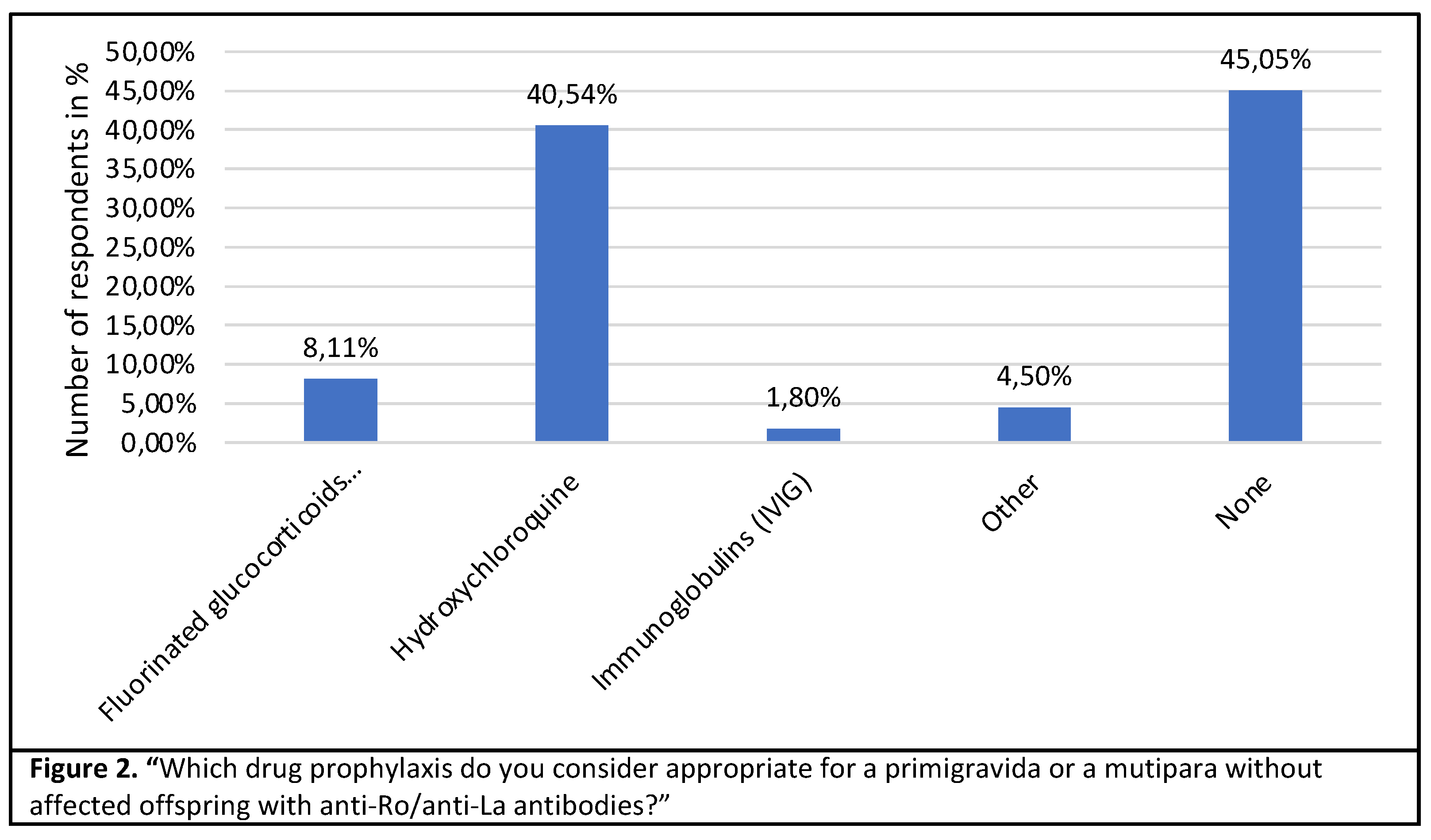

40.5% of the specialists consider prophylaxis with hydroxychloroquine to be useful in the case of a seropositive primigravida. While 45 % do not recommend any drug prophylaxis, 8% would start fluorinated steroids as prophylaxis. (Figure 2).

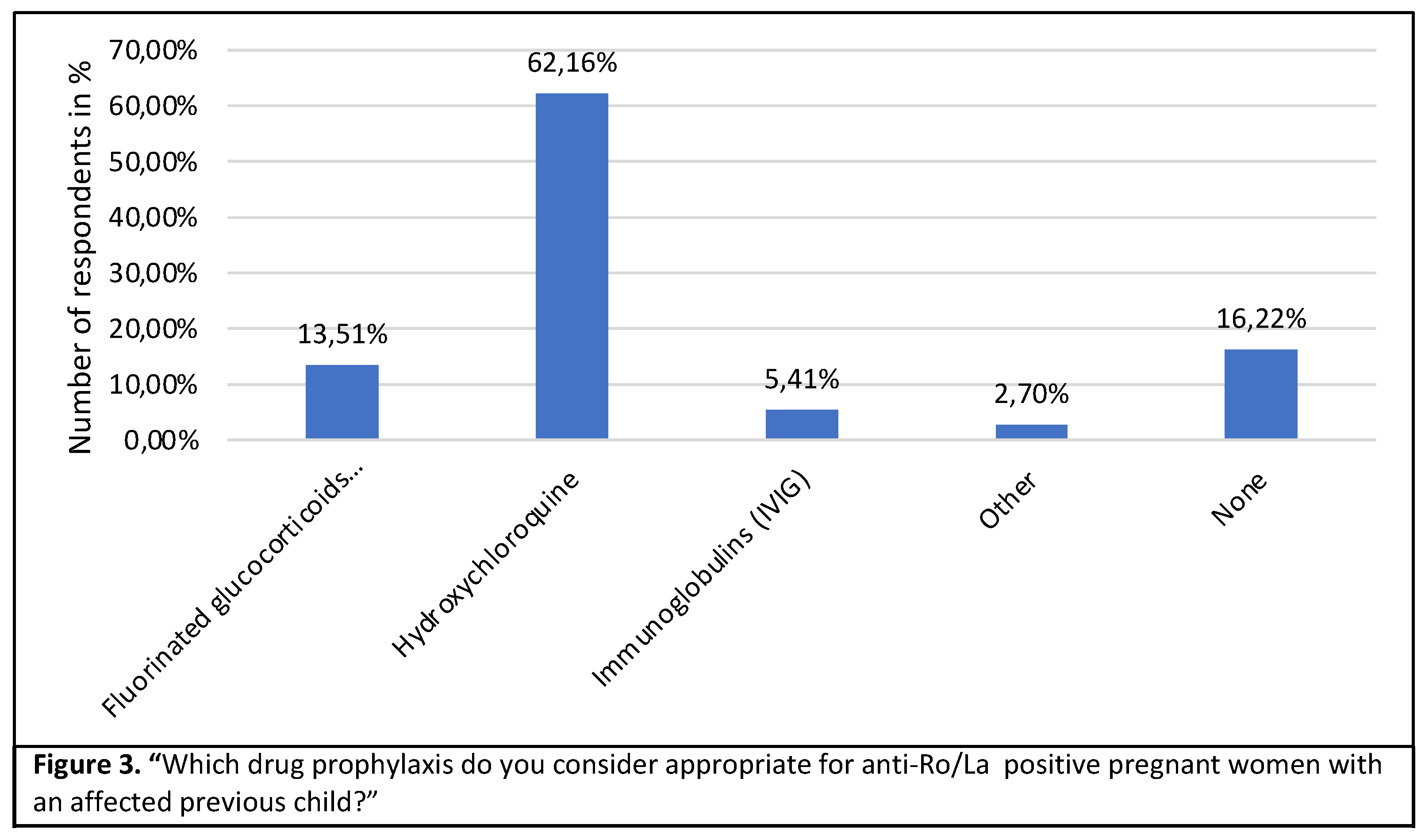

In the case of a mother who has had a previous affected pregnancy, 62,2% would support preventive treatment with hydroxychloroquine, 13.5% would give fluorinated steroids and 16% would not give any prophylaxis at all (Figure 3).

The data on the treatment of congenital AV block I-III° is summarized in

Table 1.

Table 1.

Treatment of congenital AV block I-III.

Table 1.

Treatment of congenital AV block I-III.

|

| AV block I° |

|

| No treatment |

63 (57.80%) |

| Fluorinated glucocorticoids |

27 (24.77%) |

| IVIG |

3 (2.75%) |

| Fluorinated glucocorticoids + IVIG |

9 (8.26%) |

| Hydroxychloroquine |

7 (6.42%) |

| Betamimetics |

0 (0%) |

| AV block II° |

|

| No treatment |

41 (37.96%) |

| Fluorinated glucocorticoids |

40 (37.04%) |

| IVIG |

5 (4.63%) |

| Fluorinated glucocorticoids + IVIG |

22 (20.37%) |

| Betamimetics |

0 (0%) |

| AV block III° |

|

| No treatment |

55 (50.93%) |

| Fluorinated glucocorticoids |

22 (20.37%) |

| IVIG |

4 (3.70%) |

| Fluorinated glucocorticoids + IVIG |

24 (22.22%) |

| Betamimetics |

3 (2.78%) |

When asked how quickly a complete AV block can develop, 16.4% answered with less than 12 hours, 38.2% with 12-24 hours, 9.1% with over 24 hours and 36.4% stated that they don´t know. However, 61% believe that the course of the disease and the prognosis of the fetus is more favorable with early treatment.

3.3. Pregnancy monitoring

Of the participating specialists 47.3% perform weekly echocardiography in anti-Ro/anti-La antibody positive pregnant women, 36.4% prefer biweekly controls, 9.1% follow a different schedule and 2.7% do not perform any intensified monitoring. The current practice of weekly fetal echocardiography with monitoring of the AV conduction is considered beneficial by 52.6%, but not by 19%. The remainder did not provide any information. Almost 94% of the participants do not instruct pregnant women at risk to undergo home monitoring using handheld doppler. Only 6.4% stated that they do so. However, 64% respondents could imagine instructing affected patients in self-monitoring in the future. Some participants had concerns about implementing homemonitoring, these are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Concerns regarding home monitoring

Does not change the management

Measurement uncertainties/ false positive contacts

Increases anxiety of patients

No convincing evidence so far

Too time-consuming to implement

|

Total 42 (100%)

9 (21.43%)

15 (35.71%)

9 (21.43%)

7 (16.67%)

2 (4.76%)

|

Immunglobulin (IVIG) therapy, antibody quantification and risk cut-off

When asked whether the participants could start treatment with immunoglobulins within 12 hours in the setting/infrastructure in which they work, 55% answered that they could provide IVIG within 12 hours and 45% answered that they could not. 89.9% of the participants are in favor of a cut-off for anti-Ro/anti-La antibodies for a specific risk classification and risk-adapted monitoring.

3.4. Suggestions & comments

22% of the participating ultrasound specialists left suggestions or comments on the subject. 24% reported that they are interested in the results of the survey and would like to be informed about it. Another 24% would like to have standardized algorithms or guidelines for the care of pregnant women with ant-Ro/anti-La antibodies.

3.5. Home monitoring

3.5.1. Recruitment and participation

From January 2021 to December 2023, 12 study participants were recruited and monitored by our study center. Of those recruited, 11 (91.67%) completed the study. One patient did not complete the homitoring without giving a reason.

Characteristics of the study group

Maternal characteristics are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3. Maternal Characteristics

Ethnicity

Causasian

Asien

Mixed

|

9 (75%)

2 (16.7%)

1 (8.3%)

|

Highest school degree

High school

University degree

Languages

German

Poor knowledge

Moderate knowledge

Fluent

English

Poor knowledge

Moderate knowledge

Good knowledge

Fluent

Turkish

Fluent

Diagnosis

Lupus erythematosus

Antiphospholipid syndrome

Sjögren syndrome

Rheumatoid arthritis

Obstetrical history

Primigravida

Multigravida

Previous miscarriage

|

5 (41.7%)

7 (58.3%)

1 (8.3%)

1 (8.3%)

10 (83.3%)

1 (8.3%)

4 (33.3%)

6 (50%)

1 (8.3%)

1 (8.33%)

8 (66.7%)

1 (8.3%)

2 (16.7%)

1 (8.3%)

8 (66.7%)

2 (16.7%)

4 (33.3%)

|

Most mothers were of Caucasian origin (75%) and were fluent in German language (83,33%). The average maternal age at the beginning of the study was 32.2 ± 4 years (range between 23 and 39 years). The mean gestational age at initial visit of the patient was 16 ± 4.1 weeks of gestation and at the beginning of home monitoring 18.3 ± 2.9 weeks of gestation. 66.67% of the enrolled women were primiparous. The most common rheumatic diseases among the mothers were lupus erythematosus with additional evidence of APS antibodies (41.7%) and isolated lupus erythematosus (25%). In two of the 12 pregnant women, treatment with hydroxychloroquine was initiated due to the current pregnancy. 33,3% (4/12) mothers received hydroxychloroquine already before the current pregnancy, 33% were treated with Metylprednisolon. None of the enrolled women had a previously affected child. Four mothers had a previous miscarriage. Nine out of 12 (75%) women had planned their current pregnancy. Eight women (66.67%) reported that they had a consultation with their Gynecol.ogist or rheumatologist before their pregnancy, four (33.33%) did not. When questioned whether the mothers felt sufficiently informed by their Gynecol.ogist about special aspects of the course of the pregnancy or pregnancy monitoring, eight women well informed while four did not. Regarding the question whether the women felt adequately educated by their rheumatologist, nine women confirmed.

3.5.2. Results of home monitoring

The 12 enrolled mothers returned a total of 83 weekly documentation forms. In 81.93% women fully completed the home monitoring protocol - measuring the fetal heart rate three times a day using handheld doppler. That means that they carried out 1428 of a total of 1743 fetal heart rate measurements. Reasons for not performing fetal heart rate measurements included that the women forgot the doppler device while while travelling. For multiparous women, everyday life with another infant was the main reason why measurements were omitted. None of the patients contacted the center during the entire period due to an abnormal fetal heart rate or problems/insecurities with measurement.

In 53% of the weekly documentation forms, the women agreed or fully agreed that they felt empowered by home monitoring. 46% neither agreed nor disagreed and 1% did not feel empowered. In 14.5% of the weekly responses, the mothers stated that they felt more stressed because of self-monitoring. In 30.12% participants neither agreed nor disagreed, in 50.60% they disagreed and in 4.82% they strongly disagreed.

4. Discussion

Our study focused on the standard of care for pregnant women with anti-Ro/La antibodies in Germany and the feasibility of home monitoring in a university setting. Home monitoring in this context does not only mean carrying out a fetal heart rate measurement by the pregnant woman herself several times a day, but also creating an environment in which the pregnant woman is trained sufficiently, can reach an institution 24 hours a day and get the appropriate control and medication in the presumed time slot. We also wanted to evaluate whether home monitoring leads to increased and possibly unnecessary contact ("false alarm") with the medical facility. Given the extremely rare event rate and the small number of cases in our collective, it was not the aim of this study to determine the success rate of timely treatment of emergent CHB with anti-inflammatory medication.

There are several important findings in this survey and prospective surveillance study of anti-Ro/SSA–positive pregnancies.

1. In respect of fetal surveillance there were some trends but no clear consensus on how to monitor these pregnancies.

Approximately 50 % of participating experts offer fetal echocardiography weekly, 37% every second week. 9% have an individualized scheme and almost 3% do not offer intensified surveillance in the time between 18-26 weeks GA. 28% is not sure if weekly control of AV conduction time is beneficial. Home monitoring is offered only by 6% but 67% have a positive attitude towards home monitoring and could imagine using it in their daily routine.

2. In respect of medical prophylaxis of CHB, there was no consensus between the different experts. In a pregnant woman without affected off-spring primigravida or non-affected previous pregnancy), 8% would offer fluorinated Steroids, 40% Hydroxychloroqine and 2% IVIG. 45% would offer no prophylactic treatment. In case of an affected previous pregnancy, 62% would offer Hydroxychloroqine and 16% would offer no prophylactic treatment.

3. In respect of treatment of CHB, 58% would not treat a first degree CHB, 38% would not treat a second degree or emergent CHB and 51% would not treat a complete fetal heart block. 61% belief that early detection and treatment would have a positive impact on overall prognosis. 55% of respondents reported working in a setting where IVIG is available and can be administered within 12 hours.

4. Home monitoring by hand-held Doppler 3 times a day could be carried out by most pregnant women, regardless of their origin or knowledge of the German language. Most participants had a positive or neutral attitude towards home monitoring. There was no increased rate of unnecessary contact/false positives with our center. The training of the patients could be easily integrated into our outpatient clinic setting.

Previous surveillance of anti-Ro/anti-La positive pregnancies has been founded on the hypotheses that anti-Ro/SSA–mediated CHB progresses over time, and treatment in the early stages could restore normal conduction. The PRIDE study showed, that complete fetal CHB could develop in between the interval of weekly echocardiography and that there was no continuous transition from normal rhythm to prolonged AV conduction time to first, second and third degree heart block[

29]. Cuneo et al could show, that other cardiac affections associated with anti-Ro/La antibodies did not precede CHB but were detectable in fetuses with second and third degree CHB[

25]. The definition of first degree CHB is controversial[

25,

31]. While incomplete CHB is a potentially reversable condition, complete CHB is irreversible and not amenable to anti-inflammatory treatment[

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. Transition from normal rhythm to complete heart block can develop in less than 12 hours[

24,

25,

27]. Cardiac fetal and neonatal lupus is exceedingly rare and affects only 1-2% primigravid women or women with an unaffected previous offspring[

5,

6]. Weekly or bi-weekly fetal echocardiography therefore will only serendipitously detect emergent CHB. Most women under intense surveillance will never develop a problem and the ones in need would not be detected by this approach. This current practice therefore consumes both, human and economic resources without any demonstrable benefit[

37]. Treatment with fluorinated steroids has not just benefits but also well-known side effects[

21,

38,

39,

40,

41]. The dosage was largely determined empirically. Their use should be limited to a very well-defined group of patients in a research protocol. IVIG is expensive and not easily available in an outpatient setting. The only proven secondary prevention is Hydroxychloroquine starting before 10 weeks GA as a secondary prophylaxis in women with a previously affected fetus[

14].

Costedoat-Chalumeau et al. have therefore questioned the dogma of current surveillance practice[

31]. She advocates an individualized approach in a scientific setting and considers home monitoring to be a promising approach. Evers et al. has shown, that current screening strategies are not efficient and cost effective and supports risk stratification by antibody quantification[

37]. Clowse et al. and Carvalho et al. could show trends but no consensus in surveillance, prevention and treatment of women with anti-Ro/La antibodies[

32,

42]. This is in accordance with the findings of our survey. Cuneo et al could show that ambulatory FHR surveillance of anti-SSA-positive pregnancies is feasible, has a low false positive rate and is empowering to mothers[

19]. In our study on the feasibility of home monitoring in a single center university setting we have been able to confirm this statement.

4.1. Strengths and limitations

This is the first survey evaluating the of surveillance for women with anti-Ro/La antibodies in Germany. It gives insight in current practice and illuminates on differences in the treatment approach of a high number of highly qualified participants working in different clinical settings. Based on these findings we can show that there is an immanent need for a guideline, homogenization of surveillance, care and treatment based on the individual risk and not solely on the single fact, that a woman is anti-Ro/La positive. This includes quantification of antibodies which we have recently implemented, and home monitoring by hand-held doppler with the possibility to be seen and treated within 12 hours after abnormal heartbeat is detected.

A limitation is the small number of participants in our single center clinical prospective trial. Our university setting with 24 hours service, an excellent institute for Clinical Immunology that provides us with IVIG whenever needed and allows us for extensive counselling of our patients may not be applicable to other settings. Our findings must be confirmed in a larger number of patients, seen in different clinical contexts.

5. Conclusions

There are some trends, but no clear consensus in respect of surveillance, prophylaxis, and treatment of pregnant women with anti-Ro/La antibodies between specialists in prenatal ultrasound in Germany. Intensified fetal monitoring by hand-held Doppler is possible and does not lead to frequent and unnecessary contact with the center of care. It is accepted by patients and prenatal medicine specialists as an option for intensified monitoring. It can be included into an algorithm for surveillance. Individual risk stratification, for example by antibody quantification, can help to individualize patients’ surveillance and is welcomed by most experts. Evidence-based guidelines can help to optimize the care of anti-Ro/La positive pregnant women.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. supplementary material 1–3

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.B. methodology, I.B..; software, D.K..; validation, I.B., formal analysis. D.K.; investigation, I.B., D.K. resources, R.A-F., I.B. data curation, D.K..; writing—original draft preparation, I.B.; D.K. writing—review and editing, C.K., U.S..; supervision, R.A-F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Medicine at the Justus-Liebig University Giessen (AZ 225/121).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was received from all subjects that elected to participate in this prospective study to determine the utility of daily fetal Doppler heart rate monitoring at home.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

R.A-F. is guest editor of this special edition. This should have nor influence on the contend of this article.

References

- Rozenblyum, E.V.; Sukhdeo, S.; Jaeggi, E.; Hornberger, L.; Wyatt, P.; Laskin, C.A.; Silverman, E.D. A42: Anti-Ro and Anti-La Antibodies in the General Pregnant Population: Rates and Fetal Outcomes. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014, 66, S63–S63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyon, J.P.; Saxena, A.; Izmirly, P.M.; Cuneo, B.; Wainwright, B. Neonatal lupus: Clinical spectrum, biomarkers, pathogenesis, and approach to treatment. In: Systemic Lupus Erythematosus [Internet]. Elsevier; 2021 [cited 2023 Dec 5]. p. 507–19. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/B9780128145517000532.

- Buyon, J.P.; Saxena, A.; Izmirly, P.M. Neonatal Lupus. In: Systemic Lupus Erythematosus [Internet]. Elsevier; 2016 [cited 2021 Aug 7]. p. 451–61. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/B9780128019177000516.

- Keogan, M.; Kearns, G.; Jefferies, C.A. Extractable Nuclear Antigens and SLE: Specificity and Role in Disease Pathogenesis. In: Systemic Lupus Erythematosus [Internet]. Elsevier; 2011 [cited 2023 Dec 9]. p. 259–74. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/B9780123749949100154.

- Brucato, A.; Frassi, M.; Franceschini, F.; Cimaz, R.; Faden, D.; Pisoni, M.P.; Muscarà, M.; Vignati, G.; Stramba-Badiale, M.; Catelli, L.; et al. Risk of congenital complete heart block in newborns of mothers with anti-Ro/SSA antibodies detected by counterimmunoelectrophoresis: A prospective study of 100 women. Arthritis Rheum. 2001, 44, 1832–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costedoat-Chalumeau, N.; Amoura, Z.; Lupoglazoff, J.-M.; Huong, D.L.T.; Denjoy, I.; Vauthier, D.; Sebbouh, D.; Fain, O.; Georgin-Lavialle, S.; Ghillani, P.; et al. Outcome of pregnancies in patients with anti-SSA/Ro antibodies: a study of 165 pregnancies, with special focus on electrocardiographic variations in the children and comparison with a control group. Arthritis Rheum. 2004, 50, 3187–3194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyon, J.P.; Hiebert, R.; Copel, J.; Craft, J.; Friedman, D.; Katholi, M.; Lee, L.A.; Provost, T.T.; Reichlin, M.; Rider, L.; et al. Autoimmune-Associated Congenital Heart Block: Demographics, Mortality, Morbidity and Recurrence Rates Obtained From a National Neonatal Lupus Registry. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1998, 31, 1658–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costedoat-Chalumeau, N.; Amoura, Z.; Villain, E.; Cohen, L.; Piette, J.-C. Anti-SSA/Ro antibodies and the heart: more than complete congenital heart block? A review of electrocardiographic and myocardial abnormalities and of treatment options. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2005, 7, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moak, J.P.; Barron, K.S.; Hougen, T.J.; Wiles, H.B.; Balaji, S.; Sreeram, N.; Cohen, M.H.; Nordenberg, A.; Van Hare, G.F.; Friedman, R.A.; et al. Congenital heart block: development of late-onset cardiomyopathy, a previously underappreciated sequela. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2001, 37, 238–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, S.B.; Cohen, J.; Moon-Grady, A.; Cuneo, B.; Paul, E.; Coll, A.C.; Campbell, M.; Srivastava, S. Patterns of endocardial fibroelastosis without atrioventricular block in fetuses exposed to anti-Ro / SSA antibodies. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 62, 148–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limaye, M.A.; Buyon, J.P.; Cuneo, B.F.; Mehta-Lee, S.S. A review of fetal and neonatal consequences of maternal systemic lupus erythematosus. Prenat. Diagn. 2020, 40, 1066–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliasson, H.; Sonesson, S.-E.; Sharland, G.; Granath, F.; Simpson, J.M.; Carvalho, J.S.; Jicinska, H.; Tomek, V.; Dangel, J.; Zielinsky, P.; et al. Isolated atrioventricular block in the fetus: a retrospective, multinational, multicenter study of 175 patients. Circulation 2011, 124, 1919–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, D.M.; Llanos, C.; Izmirly, P.M.; Brock, B.; Byron, J.; Copel, J.; Cummiskey, K.; Dooley, M.A.; Foley, J.; Graves, C.; et al. Evaluation of fetuses in a study of intravenous immunoglobulin as preventive therapy for congenital heart block: Results of a multicenter, prospective, open-label clinical trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2010, 62, 1138–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izmirly, P.; Kim, M.; Friedman, D.M.; Costedoat-Chalumeau, N.; Clancy, R.; Copel, J.A.; Phoon, C.K.L.; Cuneo, B.F.; Cohen, R.E.; Robins, K.; et al. Hydroxychloroquine to Prevent Recurrent Congenital Heart Block in Fetuses of Anti-SSA/Ro-Positive Mothers. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito-Zerón, P.; Izmirly, P.M.; Ramos-Casals, M.; Buyon, J.P.; Khamashta, M.A. The clinical spectrum of autoimmune congenital heart block. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2015, 11, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clancy, R.M.; Halushka, M.; Rasmussen, S.E.; Lhakhang, T.; Chang, M.; Buyon, J.P. Siglec-1 Macrophages and the Contribution of IFN to the Development of Autoimmune Congenital Heart Block. J.I. 2019, 202, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izmirly, P.; Saxena, A.; Buyon, J.P. Progress in the pathogenesis and treatment of cardiac manifestations of neonatal lupus. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2017, 29, 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnabi, E.; Boutjdir, M. Role of calcium channels in congenital heart block. Scand. J. Immunol. 2010, 72, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuneo, B.F.; Moon-Grady, A.J.; Sonesson, S.-E.; Levasseur, S.; Hornberger, L.; Donofrio, M.T.; Krishnan, A.; Szwast, A.; Howley, L.; Benson, D.W.; et al. Heart sounds at home: feasibility of an ambulatory fetal heart rhythm surveillance program for anti-SSA-positive pregnancies. J. Perinatol. 2017, 37, 226–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, A.L.; Ataullah, I.; Yates, R.; Sullivan, I.; Charles, P.; Williams, D. Congenital fetal heart block: a potential therapeutic role for intravenous immunoglobulin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 116 Suppl. 2, 543–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleeb, S.; Copel, J.; Friedman, D.; Buyon, J.P. Comparison of treatment with fluorinated glucocorticoids to the natural history of autoantibody-associated congenital heart block: Retrospective review of the research registry for neonatal lupus. Arthritis Rheum. 1999, 42, 2335–2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askanase, A.D.; Friedman, D.M.; Copel, J.; Dische, M.R.; Dubin, A.; Starc, T.J.; Katholi, M.C.; Buyon, J.P. Spectrum and progression of conduction abnormalities in infants born to mothers with anti-SSA/Ro-SSB/La antibodies. Lupus 2002, 11, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raboisson, M.-J.; Fouron, J.-C.; Sonesson, S.-E.; Nyman, M.; Proulx, F.; Gamache, S. Fetal Doppler echocardiographic diagnosis and successful steroid therapy of Luciani-Wenckebach phenomenon and endocardial fibroelastosis related to maternal anti-Ro and anti-La antibodies. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2005, 18, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, N.; Silverman, E.D.; Kingdom, J.; Dutil, N.; Laskin, C.; Jaeggi, E. Serial echocardiography for immune-mediated heart disease in the fetus: results of a risk-based prospective surveillance strategy: Prevention strategy of cardiac neonatal lupus erythemathosus. Prenat. Diagn. 2017, 37, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuneo, B.F.; Sonesson, S.-E.; Levasseur, S.; Moon-Grady, A.J.; Krishnan, A.; Donofrio, M.T.; Raboisson, M.-J.; Hornberger, L.K.; Van Eerden, P.; Sinkovskaya, E.; et al. Home Monitoring for Fetal Heart Rhythm During Anti-Ro Pregnancies. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 72, 1940–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, C.A.; Sheth, S.S. Could Timing Be Everything for Antibody-Mediated Congenital Heart Block? J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 72, 1952–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuneo, B.F.; Ambrose, S.E.; Tworetzky, W. Detection and successful treatment of emergent anti-SSA–mediated fetal atrioventricular block. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol.. 2016, 215, 527–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mawad, W.; Hornberger, L.; Cuneo, B.; Raboisson, M.; Moon-Grady, A.J.; Lougheed, J.; Diab, K.; Parkman, J.; Silverman, E.; Jaeggi, E. Outcome of Antibody-Mediated Fetal Heart Disease With Standardized Anti-Inflammatory Transplacental Treatment. JAHA 2022, 11, e023000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, D.M.; Kim, M.Y.; Copel, J.A.; Davis, C.; Phoon, C.K.L.; Glickstein, J.S.; Buyon, J.P. Utility of Cardiac Monitoring in Fetuses at Risk for Congenital Heart Block: The PR Interval and Dexamethasone Evaluation (PRIDE) Prospective Study. Circulation 2008, 117, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeggi, E.T.; Silverman, E.D.; Laskin, C.; Kingdom, J.; Golding, F.; Weber, R. Prolongation of the Atrioventricular Conduction in Fetuses Exposed to Maternal Anti-Ro/SSA and Anti-La/SSB Antibodies Did Not Predict Progressive Heart Block. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011, 57, 1487–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costedoat-Chalumeau, N.; Morel, N.; Fischer-Betz, R.; Levesque, K.; Maltret, A.; Khamashta, M.; Brucato, A. Routine repeated echocardiographic monitoring of fetuses exposed to maternal anti-SSA antibodies: time to question the dogma. Lancet Rheumatol. 2019, 1, e187–e193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, J.S.; Chaoui, R.; Copel, J.A.; Hecher, K.; Herrera, M.; Lee, W.; Paladini, D.; Tutschek, B.; Yagel, S.; Cuneo, B. OC11.04: Fetal surveillance of anti-Ro/anti-La affected pregnancies: is there a consensus? Results of an international survey. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 52, 25–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, D.; Duncanson, L.; Glickstein, J.; Buyon, J. A review of congenital heart block. Images Paediatr. Cardiol. 2003, 5, 36–48. [Google Scholar]

- Jaeggi, E.; Laskin, C.; Hamilton, R.; Kingdom, J.; Silverman, E. The Importance of the Level of Maternal Anti-Ro/SSA Antibodies as a Prognostic Marker of the Development of Cardiac Neonatal Lupus Erythematosus. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2010, 55, 2778–2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeggi, E.; Kulasingam, V.; Chen, J.; Fan, C.S.; Laskin, C.; Hamilton, R.M.; Hiraki, L.T.; Silverman, E.D.; Sepiashvili, L. Maternal Anti-Ro Antibody Titers Obtained with Commercially Available Immunoassays are Strongly Associated with Immune-Mediated Fetal Heart Disease. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2023, art.42513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyon, J.P.; Masson, M.; Izmirly, C.G.; Phoon, C.; Acherman, R.; Sinkovskaya, E.; Abuhamad, A.; Makhoul, M.; Satou, G.; Hogan, W.; et al. Prospective Evaluation of High Titer Autoantibodies and Fetal Home Monitoring in the Detection of Atrioventricular Block Among Anti-SSA/Ro Pregnancies. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evers, P.D.; Alsaied, T.; Anderson, J.B.; Cnota, J.F.; Divanovic, A.A. Prenatal heart block screening in mothers with SSA/SSB autoantibodies: Targeted screening protocol is a cost-effective strategy. Congenit. Heart Dis. 2019, 14, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Berg, N.W.E.; Slieker, M.G.; van Beynum, I.M.; Bilardo, C.M.; de Bruijn, D.; Clur, S.A.; Cornette, J.M.J.; Frohn-Mulder, I.M.E.; Haak, M.C.; van Loo-Maurus, K.E.H.; et al. Fluorinated steroids do not improve outcome of isolated atrioventricular block. Int. J. Cardiol. 2016, 225, 167–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, L.M.; Tavares, G.M.P.; Damiano, A.P.; Lopes, M.A.B.; Aiello, V.D.; Schultz, R.; Zugaib, M. Perinatal outcome of fetal atrioventricular block: one-hundred-sixteen cases from a single institution. Circulation 2008, 118, 1268–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costedoat-Chalumeau, N.; Amoura, Z.; Le Thi Hong, D.; Wechsler, B.; Vauthier, D.; Ghillani, P.; Papo, T.; Fain, O.; Musset, L.; Piette, J.-C. Questions about dexamethasone use for the prevention of anti-SSA related congenital heart block. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2003, 62, 1010–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, A.; Radwan, A.A.; Ali, A.K.; Abd-Elkariem, A.Y.; Shazly, S.A. Use of antenatal fluorinated corticosteroids in management of congenital heart block: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol.. Reprod. Biol. : X 2019, 4, 100072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clowse, M.E.B.; Eudy, A.M.; Kiernan, E.; Williams, M.R.; Bermas, B.; Chakravarty, E.; Sammaritano, L.R.; Chambers, C.D.; Buyon, J. The prevention, screening and treatment of congenital heart block from neonatal lupus: a survey of provider practices. Rheumatology 2018, 57, v9–v17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).