1. Introduction

Ovarian cancer ranks third in frequency after cervical and uterine cancer in gynecological oncology and has the highest mortality rate among these cancer types. In 2020 313,959 cases of ovarian cancer were identified by Globocan (Global Cancer Observatory), and 207,252 deaths were registered as a result of this disease [

1]. The median age at the diagnosis was 63, and the median 5-year relative survival was 49.7% [

2]. The risk of getting ovarian cancer for women during their lifetime is about 1 in 78, and the chance of dying from ovarian cancer is about 1 in 108 [

3].

According to the data of the Statistical Group in the National Center of Oncology, which operates as a part of the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Armenia, in 2022, 197 women were diagnosed with ovarian cancer in Armenia. The morbidity and mortality rates in Armenia per 100,000 female population were 6.6 and 2.6, respectively [

4]. The first-line therapy includes debulking surgery followed by adjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy. In some cases, for patients with bad performance status and comorbidities and a very advanced disease when upfront optimal cytoreduction is technically not feasible, treatment may start from chemotherapy followed by surgery [

5,

6,

7]. The poor treatment outcomes of patients with ovarian cancer are mainly explained by the high incidence of recurrence after the completion of primary treatment which is observed in 25% of cases with early-stage diseases and more than 80% with more advanced stages, within 5 years after primary treatment, leading to rapid progression of the disease, development of severe complications, and death [

8,

9]. Currently, the main issues in ovarian cancer, which are responsible for the high mortality and low 5-year survival rate, are:

lack of effective screening [

10,

11],

high frequency of relapse [

8,

9],

limited opportunities for radical surgery and systemic treatment [

12].

When planning the treatment strategy for ovarian cancer relapse, accurate classification is the key. The classification of ovarian cancer recurrence is based on the time from the end of platinum-containing chemotherapy to the appearance of signs of disease and is divided into three categories: platinum-sensitive relapse, where the duration of platinum-free interval exceeds 6 months, platinum-resistant relapse, where the duration of interval without platinum is less than 6 months and platinum-refractory relapse: where progression of the tumor process occurred during or immediately after a platinum containing chemotherapy [

13,

14,

15]. The choice of therapy for relapse depends on various criteria such as tumor biology, the patient’s general condition (ECOG), toxicity, previous chemotherapy, and response to chemotherapy [

16]. Platinum-based chemotherapy remains the backbone of the treatment of recurrent ovarian cancer, meanwhile, the use of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors and anti-angiogenic (anti-VEGF) agents as maintenance therapy have led to significant improvements in both progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) [

17,

18].

For convenience, guidelines proposed by globally accepted networks, such as the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), combine platinum-resistant and platinum-refractory relapses in one group, as the primary treatment and prognosis are similar between these groups [

5]. In our study, we will similarly combine the data for these 2 types of recurrence.

Currently, there is no convincing data to determine the optimal regimen and sequence of systemic therapy, as the efficacy of different regimens is comparable, however, there are few adequate and well-designed comparative studies regarding ovarian cancer recurrence.

For patients with platinum-sensitive relapse, it is acceptable to use platinum-containing chemotherapy in combination with other agents, depending on the toxicity profile [

19]. Some clinical trials have demonstrated the benefit of adding PARP inhibitors (Olaparib, Rucaparib, Niraparib, etc.) to the treatment regimen [

20,

21,

22,

23].

Platinum-resistant ovarian cancer recurrences are the most unfavorable and severe in terms of prognosis and effectiveness of therapy. Therefore, chemotherapy for these relapses remains one of the most difficult tasks in modern oncology. Since the relapse of the disease occurs immediately after or during the first line of therapy, combined therapy with platinum-containing agents no longer leads to improved long-term outcomes, instead, it increases the toxicity, leading to the worsening in patients’ performance status [

24,

25,

26]. Resistance to platinum agents is a complex process that has multiple mechanisms involving both, tumor cell type, as well as tumor microenvironment [

27].

There is no evidence to support an order of sequencing platinum combinations. Nevertheless, platinum-based chemotherapy remains the cornerstone of the systemic treatment of relapsed ovarian cancer and should be used in all patients until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity, such as severe allergy to platinum and others. Recommendations for the relapsed ovarian cancer treatment are limited to listing the medications and their combinations, without specifying the criteria for their use.

The primary outcome of our study aimed to determine the overall survival (OS) of relapsed ovarian cancer patients depending on the type of relapse, stage of the disease, and age of the patients. The secondary outcome was determining OS and progression-free survival (PFS) based on the treatment regimen.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

The clinical material of this research is the data of patients with relapses of ovarian cancer, who were treated in the oncology and chemotherapy departments of the National Centre of Oncology named after Fanarjyan, the Oncology Clinic of Mikaelyan Institute of Surgery and the Chemotherapy Clinic of Muratsan University Hospital in Armenia. Patient information was obtained from the case histories and outpatient cards, which were coded based on a pre-compiled coder using the scoring system displayed in the coder.

The data on the current condition of the patients were obtained from the “Armed” (Armed Health) application integrated into the national centralized system of electronic healthcare of Armenia. A retrospective analysis of primary records of patients receiving chemotherapy for platinum-sensitive and platinum-resistant relapsed ovarian cancer was performed. The study included patients, who had relapsed ovarian cancer confirmed between 2009–2019, with at least a 3-year follow-up after recurrence.

2.2. Stratification According to the Remission Type

Within the framework of the study, we examined data of the patients meeting the following criteria: presence of morphologically confirmed stage I–IV ovarian cancer (including Primary Peritoneal and Fallopian Tube cancer) and recurrence after single and/or combination chemotherapy based on Cisplatin or Carboplatin agents during treatment, within 6 months after completing treatment (platinum-resistant) and more than 6 months after treatment (platinum-sensitive).

The type of relapse was assessed based on the time from the end of the previous line of chemotherapy and the recurrence of the disease. The assessment of the duration of remission and the fact of remission was carried out according to the accepted standards:

In line with the general recommendations, we defined a complete response as the disappearance of all pathological lesions (both clinical and radiological) with the regulation of the CA-125 serum tumor marker level (≤35 U/mL). A partial response was defined as partial clinical improvement with a greater than 25% (but not complete) reduction in CA-125 serum tumor marker levels and radiological regress of the tumor mass. The disease was assessed as progressive when the patient’s clinical condition worsened or the level of the tumor marker CA-125 increased by more than 25% or radiological progression was confirmed. All other conditions were considered stable disease. The staging was done according to the FIGO international staging system accepted as a standard in gynecological oncology [

28].

Progression-free survival (PFS) was estimated from the time of diagnosis to the time of progression or death, whereas overall survival (OS) was calculated from the time of the first relapse to death due to any cause.

2.3. Features and Data Analysis

The statistical analysis of the obtained data was carried out using the SPSS Statistics 23 computer program. For data analysis, depending on the type of relapse, survival up to 1 year, 1 year, 2 years, 3 years, and 5 years were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier non-parametric statistical method, during which Log Rank (Mantel-Cox) statistical test was performed. p-value < 0.05 was deemed statistically significant. Categorical variables were compared by the chi-square test.

X2 Pearson’s test with Fisher’s exact test was used to evaluate the difference in 3- and 5-year survival by June 2023.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

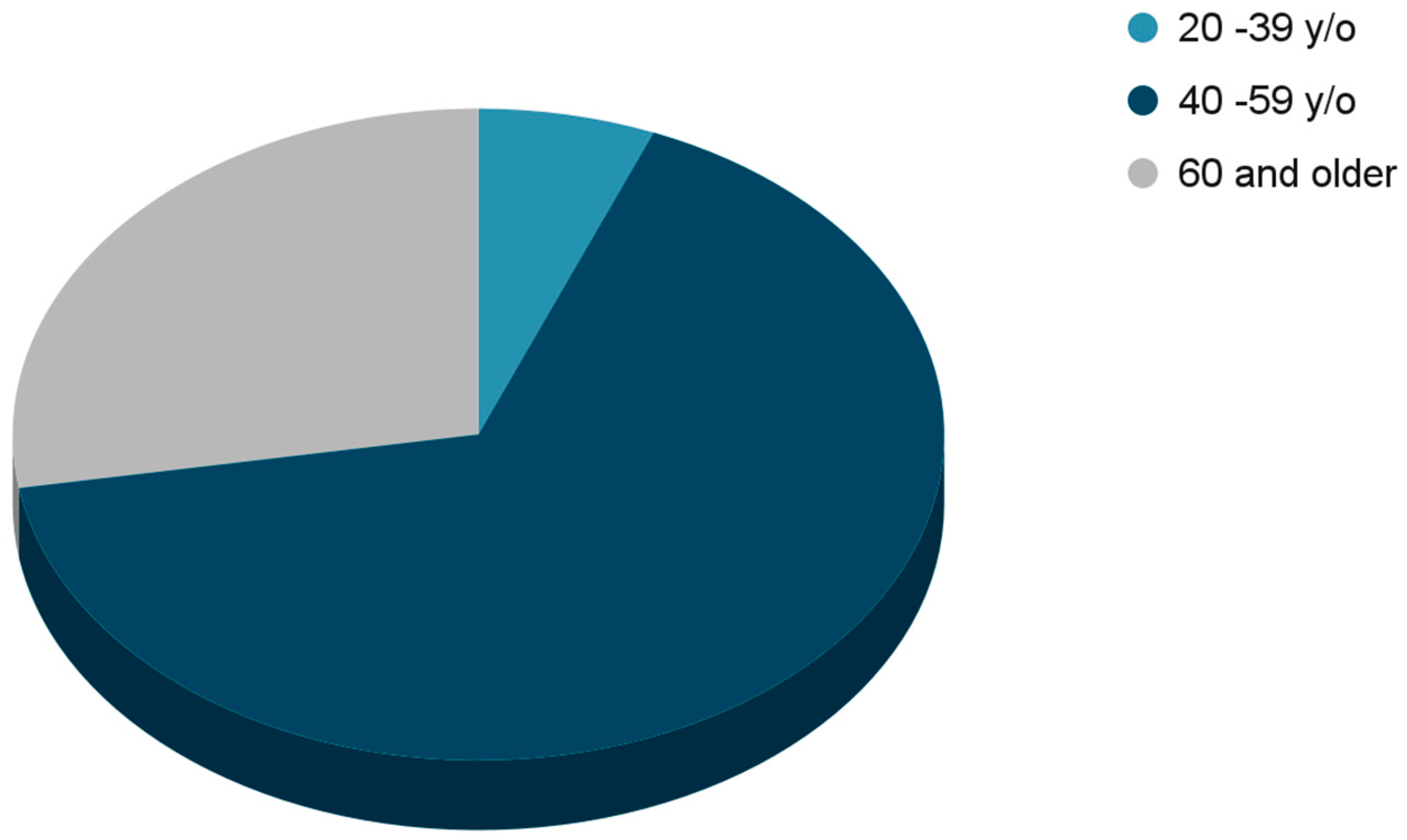

In total, 228 females were included in the study. The median age of the patients involved in the study was 55.5. The majority of the patients, 151 (66.2%) who had a disease recurrence were 40 to 59 years. The total number of analyzed patients over 60 years of age was 63 (27.6%). Only 14 (6.2%) patients in the study were at a younger age, between 20–39 years old (

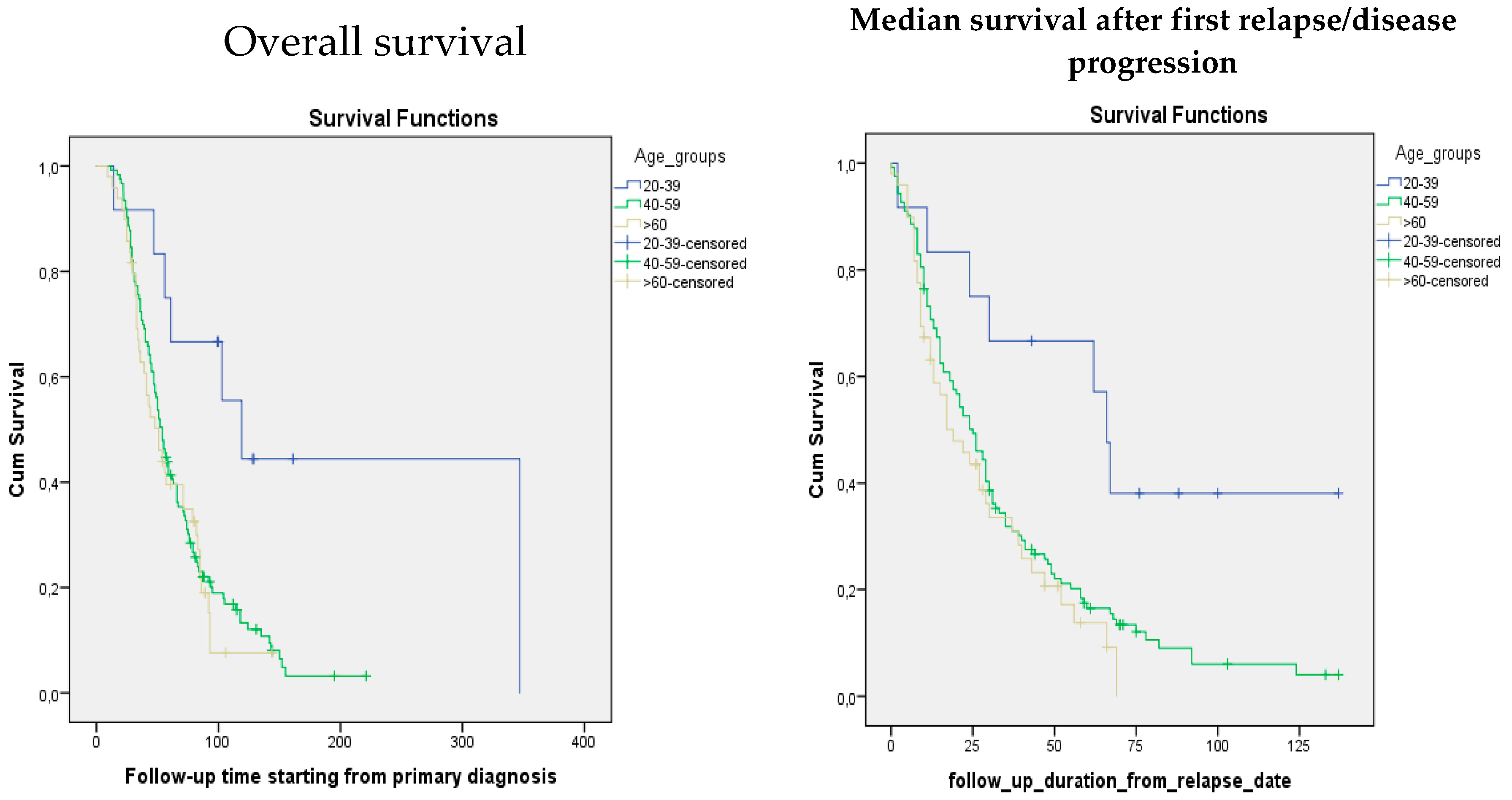

Figure 1). The median follow-up starting from the relapse was 21 (0–137) months. The median follow-up starting from the primary diagnosis was 48 (6–347) months. According to the data, from the platinum-sensitive arm, in the age group from 20 to 39, median overall survival and median survival after relapse were 119 months and 66 months, in the age group from 40 to 59: 54 months and 24 months, and finally in the elderly group with the age more than 60 years old, 51 months and 19 months, respectively. Meanwhile in the platinum-resistant arm median survival from the diagnosis and median survival after relapse were 17 months and 9 months in the 20–39 age group, 29 months and 19 months in the 40–59 age group, and 21 months and 12 months in the age group over 60, respectively (

Table 1). When comparing median survival after relapse/disease progression and overall survival, a significant difference is observed between different age groups

(p-value—

0.01). The younger age at the time of diagnosis was associated with higher survival after the disease relapse. Likewise, a similar tendency was observed in terms of overall survival

(p-value—0.006) (

Table 1;

Figure 2)

Data showed that 87.3% of the relapsed ovarian cancer patients were diagnosed with late stages of the disease (III and IV) at the primary treatment, while the proportion of early stages among patients with recurrent ovarian cancer was only 12.7%. Median OS in the platinum-sensitive relapsed group was 40 months for the patients who initially had stage I disease as shown in

Table 2. In comparison, all other stage groups had similar median OS (20–26 months), (

p-value of 0.275).

Our data showed that the incidence of platinum-sensitive relapses in the study group was 81.6%. (186 out of 228) and only 18.4% (42 out of 228) were diagnosed with platinum-resistant relapse. It is clear from the presented data that the group of patients analyzed in our study is quite homogeneous according to such main characteristics as the stage of the disease, age, and primary treatment of relapses, which allowed us to conduct statistical analysis and obtain reliable results.

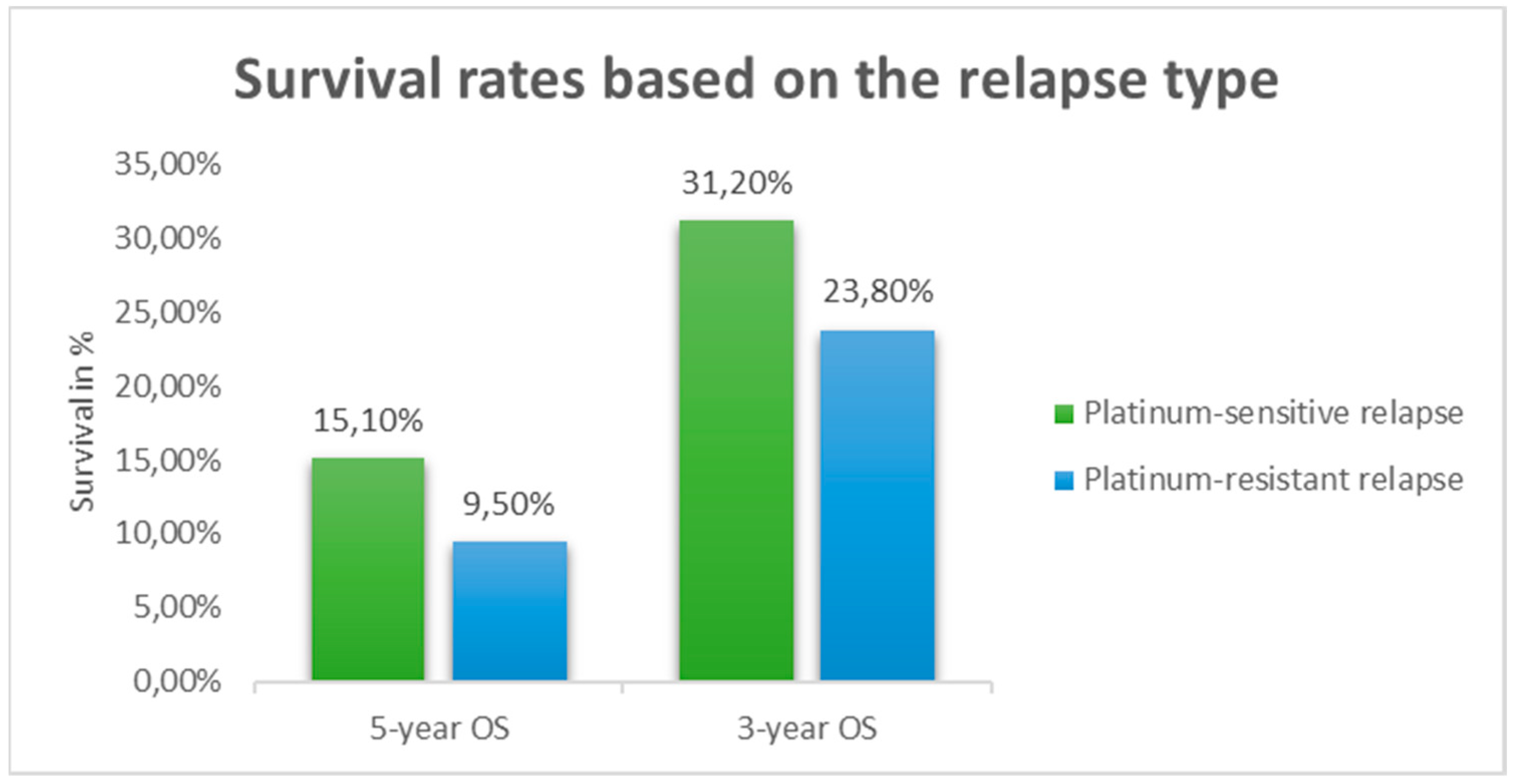

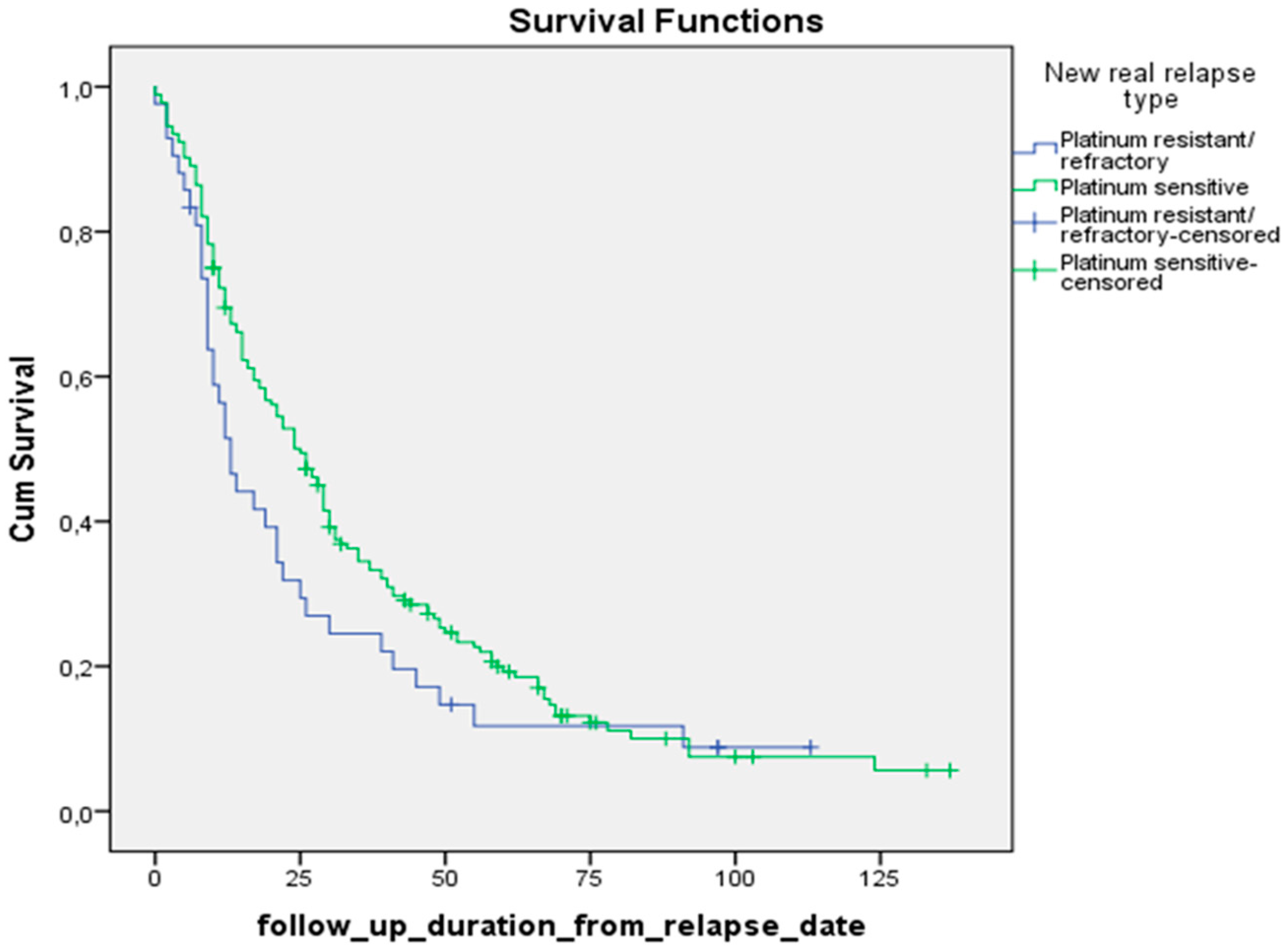

Using the Kaplan-Meier method, we calculated the median survival of patients with recurrent ovarian cancer, as well as the maximum and minimum survival times. According to our data, the median survival of the patients starting from the primary diagnosis in the platinum-sensitive compared to the platinum-resistant group was: 54 months (95% CI 48.4; 59.6) versus 25 months (95% CI 20; 30.0),

p-value 0.000. Meanwhile, median survival after relapse in these groups was: 25 months (95% CI 19.8; 30.2) and 13 months (95% CI 9.3; 16.7), respectively

(p-value 0.1113), 3-year and 5-year survival rates were: 31.2% vs. 23.8%, and 15.1% vs. 9.5%, respectively (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

3.2. Survival after Relapse Based on the Choice of the Systemic Treatment

3.2.1. Platinum-Sensitive Relapse

We possess data on the survival rates for the most frequently used regimens. These statistics showed that for platinum-sensitive relapse, the most effective regimens were found to be Paclitaxel/Carboplatin/Bevacizumab (PFS 31 months), Cyclophosphamide/Cisplatin (PFS 38.5 months), and Paclitaxel/Cisplatin (PFS 25.5 months) with the longest median PFS. Other chemotherapy regimens like Gemcitabine/Cisplatin (PFS 19.5 months), Paclitaxel/Carboplatin (PFS 18.5 months), Gemcitabine/Carboplatin (PFS 17.5 months), Gemcitabine/Carboplatin/Bevacizumab (PFS 14 months), had similar efficacy regarding PFS. The worst results were observed in the Docetaxel/Cisplatin (PFS 10.5 months) and Docetaxel/Cyclophosphamide (PFS 4 months) groups having the shortest PFS.

We analyzed also the results of 3-year and 5-year overall survival after relapse for each chemotherapy regimen in both arms. In platinum-sensitive arm patients overall following survival rates were achieved: Paclitaxel/Carboplatin (29.2% and 12.5%), Paclitaxel/Carboplatin/Bevacizumab (55.6% and 44.4%), Gemcitabine/Carboplatin (28.6% and 0), Gemcitabine/Carboplatin/Bevacizumab (66.7% and 16.7%), Gemcitabine/Cisplatin (33.3% and 13.3%), Gemcitabine (0), Cyclophosphamide (0).

3.2.2. Platinum-Resistant Relapse

We conducted a comparative analysis of the effectiveness of the regimens that were prescribed in Armenian clinics to patients who had platinum-resistant relapse with platinum-free interval (PFI) less than 6 months. 3-year OS rates after relapse for the analyzed groups were: Gemcitabine 33%, Gemcitabine/Bevacizumab 34%, Gemcitabine/Carboplatin 16.7%, Cyclophosphamide/Doxorubicin/Cisplatin 33%, liposomal Doxorubicin/Carboplatin 50%, Paclitaxel/Carboplatin 33%, p-value 0.99.

5-year survival rates after relapse were fixed only for the patients who received Paclitaxel/Carboplatin (8.3%), Gemcitabine/Carboplatin (16.7%), and Cyclophosphamide/Doxorubicin/Cisplatin (33%), p-value 0.79. In this group remission after relapse was reached only in 7 patients, therefore we didn’t include the results of the mPFS in the study, as the number of patients was too small.

4. Discussion

Our study showed that the majority of the patients with recurrent ovarian cancer involved in the study were from 40 to 59 years old. This is probably because the median age of the patients in Armenia was 55 years which is much younger compared to the statistics from the United States where the median age for this disease is 63 [

29], meanwhile eastern countries like India, ovarian cancer is seen in the younger age group, with a median age < 55 years being reported by most of the studies, in some regions of the country even <50 [

30]. This phenomenon might be attributable to the underdiagnosis and undertreatment of ovarian cancer among the elderly population in limited source settings. Our data showed that the best OS from the primary diagnosis and survival after relapse was fixed in the younger age group of the platinum-sensitive arm, which was twice higher (119 months) compared to other age groups. These results correlate with the statistics we have in the literature regarding age-connected mortality in ovarian cancer, the older the patient is the worse the survival [

31]. But when we looked at the platinum-resistant arm, the picture was different, longer survival was fixed in the middle-aged group (40–59), while the elderly and young-adult group had relatively the same lifetime. These non-intuitive results might be attributed to the small sample size in the platinum-resistant group.

According to our study results, the vast majority of patients with relapsed ovarian cancer initially had advanced FIGO stages (III and IV), the proportion of early stages among patients with recurrent ovarian cancer was about 13% percent. This data once again confirms the fact that the stage of the disease is the most unfavorable prognostic factor in ovarian cancer, emphasizing the importance of early detection [

32]. Interestingly, the median survival after relapse in the platinum-sensitive relapsed group was twice better (40 months) for the patients who initially had stage I disease. In comparison, all other stage groups had similar survival (20–26 months). This data differs from the results of the article published by Rajendra Kumar Meena in 2022 in JCO Global Oncology, where it is shown that I and II-stage patients have better survival than more advanced-stage groups [

30]. An Italian study that was carried out by Gadducci et al. also showed statistical significance between survival after recurrence and initial clinical stage (I, IIA versus IIB–IV) [

33].

Our data showed that more than 80% of the patients with ovarian cancer relapse had platinum-sensitive disease, so the majority of them had a chance to get a platinum combination again, in the absence of the comorbidities [

5,

8,

13,

14]. As a result, 3 and 5-year OS rates of platinum-sensitive relapse were almost twice as high compared to platinum-resistant type.

Platinum-sensitive relapse is considered to be a chemo-sensitive disease in more than half of the patients [

34]. As demonstrated in the results one of the most effective regimens in our study for platinum-sensitive relapsed ovarian cancer was Paclitaxel/Carboplatin

. This was also the main regimen the patients received during their primary treatment. One of the biggest advantages of this regimen is its affordability and availability. Our results are in line with the generally accepted guidelines, showing that rechallenging the “backbone’’ regimen remains one of the most effective in relapsed disease [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. A generally accepted standard of care is re-administration of platinum agent combined with one of the following medications pegylated liposomal Doxorubicin (PLD), Paclitaxel, Gemcitabine with or without VEGF inhibitor like Bevacizumab [

35,

36].

According to our analysis adding Bevacizumab to the chemotherapy regimen resulted in higher PFS and OS survival after relapse which was also shown in the AURELIA trial published in JCO by Pujade-Lauraine et al. [

37]. The shortest survival rates were observed in the patients groups who didn’t get platinum compound therapy without having a chance to reach 3 and 5-year OS.

Another regimen with high PFS in our study was Cyclophosphamide/Cisplatin, an old regimen that was used before Paclitaxel/Carboplatin became the standard of care. Our result was different from the data published in the New England Journal of Medicine by McGuire WP who showed the superiority of Paclitaxel/Cisplatin in terms of OS and PFS [

38].

One of the goals of our study was to evaluate the efficacy of different regimens in the treatment of platinum-resistant relapses and their impact on 3- and 5-year survival rates after relapse. The generally accepted standard of care for platinum-resistant ovarian cancer is single-agent chemotherapy with non-platinum agents like Gemcitabine, Docetaxel, Paclitaxel, Topotecan, pegylated liposomal Doxorubicin, etc. [

39,

40,

41].

As we have already demonstrated, the 3-year survival rate after relapse for patients with platinum-resistant relapses was 23.8%, and the 5-year survival rate after relapse was only 9.5%. The main monotherapy regimen that showed better survival rates was Gemcitabine. Our study didn’t demonstrate survival benefit with bevacizumab in this group of patients. Interestingly, some patients received platinum compounds in the relapse treatment while having platinum-free intervals of less than 6 months which is not a standardized accepted approach, nevertheless, only these groups of patients (Paclitaxel/Carboplatin, Gemcitabine/Carboplatin, Cyclophosphamide/Doxorubicin/Cisplatin) could reach 5-year survival after relapse. This can be explained by the retrospective analysis done by the Australian Ovarian Cancer Study according to which overall survival was improved after platinum-based chemotherapy even in patients with a platinum-free interval of less than 6 months (median OS 17.7 months after platinum-based chemotherapy versus 10.6 months after a non-platinum regimen patients with a TFIp months). On the opposite, a platinum-free interval of more than 6 months does not necessarily guarantee a response to future platinum-based chemotherapy [

18,

42].

It should be recognized and emphasized that, among other factors, the availability and accessibility of the medications, especially in a developing country, like Armenia, very often has a big impact on the choice of anti-relapse treatment regimen. There is a lack of treatment accessibility due to insufficient government coverage and limited availability of essential medications [

43].

The study has certain limitations, including the following.

Due to its retrospective design, notably, there was inadequate documentation of important details in the medical records, particularly, regarding treatment-related toxicity.

Most of the relapsed patients received only chemotherapy, because of lack of access to the targeted therapy. A number of targeted agents like Bevacizumab, PARP inhibitors (Olaparib, Rucaparib, Niraparib), immunotherapy (Pembrolizumab, Dostarlimab), Folate receptor Alfa inhibitor—Marvetuximab Soravtansine-gynx are out of pocket for Armenian patients. Except for Bevacizumab, which was available for very few patients, all other abovementioned agents are not even registered in Armenia.

In our study we didn’t take into consideration the impact of the ‘’second look’’ surgery during the treatment of the recurrence.

5. Conclusions

The present analysis will contribute to the improvement of the treatment outcomes of ovarian cancer patients with relapse. Overall, despite new therapeutic approaches, ovarian cancer continues to be one of the deadly malignant diseases in women, especially, in developing countries with a lack of resources, where, in fact, the main available systemic treatment for the majority of the patients remains chemotherapy. The persistently low survival rates emphasize the urgent need for more research on this group of patients with poor outcomes.

Author Contributions

L.H.—Project administration, Data curation, Supervision, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing, Investigation. E.M.— Visualization, Conceptualization, Writing—review and editing. S.B.—Visualization, Conceptualization, Writing—review and editing. N.K.—Visualization, Conceptualization, Writing—review and editing. A.J.— Data curation, Writing—review and editing. G.T.— Visualization, Writing—review and editing. A.A.—Writing—review and editing. L.S.—Writing—review and editing. D.Z.—Writing—review and editing. N.M.—Writing—review and editing. A.A.—Writing—review and editing. A.G.—Writing—review and editing. M.S.—Writing—review and editing. M.H.—Writing—review and editing. H.N.—Data curation, Investigation. A.S.—Data curation, Investigation. A.G. Writing—review and editing. S.D.—Conceptualization, Writing—review and editing. A.M.—Conceptualization, Project administration, Supervision, Visualization. G.J.—Conceptualization, Project administration, Supervision, Visualization, Writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Yerevan State Medical University.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was waived, as the study was a retrospective audit of the medical records.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

LH reports lecture fees and travel support from Roche and Novartis Pharmaceuticals outside of the submitted work.

References

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. The Global Cancer Observatory (Globocan), December 2020. Available online: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/cancers/25-Ovary-fact-sheet.pdf (accessed on December 2020.).

- National Cancer Institute. SEER Cancer Statistics Factsheets: Ovary Cancer. Available online: https://ocrahope.org/get-the-facts/statistics/#:~:text=A%20woman’s%20lifetime%20risk%20of%20dying%20from%20invasive%20ovarian%20cancer,ovarian%20cancer%20is%2049.7%25%20percent (accessed on November 2023).

- American Cancer Society. Key Statistics of Ovarian Cancer. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/ovarian-cancer/about/key-statistics.html (accessed on Oct 3, 2023 ).

- Ministry of Health of Armenia. Cancer Statistics. Available online: https://moh.am/#1/0 (accessed on June 2023).

- NCCN Guidelines Version 2.2023 Ovarian Cancer\Fallopian Tube Cancer\Primary Peritoneal Cancer. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/guidelines-detail?category=1&id=1453 (accessed on June 2, 2023).

- Jiang, R.; Zhu, J.; Kim, J.-W.; Liu, J.; Kato, K.; Kim, H.-S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Zhu, T.; Aoki, D.; et al. Study of upfront surgery versus neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by interval debulking surgery for patients with stage IIIC and IV ovarian cancer, SGOG SUNNY (SOC-2) trial concept. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2020, 31, e86. https://doi.org/10.3802/jgo.2020.31.e86. [CrossRef]

- Tsonis, O.; Gkrozou, F.; Vlachos, K.; Paschopoulos, M.; Mitsis, M.C.; Zakynthinakis-Kyriakou, N.; Boussios, S.; Pappas-Gogos, G. Upfront debulking surgery for high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma: current evidence. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020, 8, 1707. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-1620. [CrossRef]

- Garzon, S.; Laganà, A.S.; Casarin, J.; Raffaelli, R.; Cromi, A.; Franchi, M.; Barra, F.; Alkatout, I.; Ferrero, S.; Ghezzi, F. Secondary and tertiary ovarian cancer recurrence: what is the best management?. Gland. Surg. 2020, 9, 1118–1129. https://doi.org/10.21037/gs-20-325. [CrossRef]

- Salani, R.; Backes, F.J.; Fung, M.F.K.; Holschneider, C.H.; Parker, L.P.; Bristow, R.E.; Goff, B.A. Posttreatment surveillance and diagnosis of recurrence in women with gynecologic malignancies: Society of Gynecologic Oncologists recommendations. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011, 204, 466–478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2011.03.008. [CrossRef]

- Patni, R. Screening for Ovarian Cancer: An Update. J. Mid-Life Health 2019, 10, 3–5. https://doi.org/10.4103/jmh.JMH_46_19. [CrossRef]

- The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Available online: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/ovarian-cancer-screening (accessed on Feb 13, 2018).

- Song, Y.J. Prediction of optimal debulking surgery in ovarian cancer. Gland. Surg. 2021, 10, 1173–1181. https://doi.org/10.21037/gs-2019-ursoc-08. [CrossRef]

- Fung-Kee-Fung, M.; Oliver, T.; Elit, L.; Oza, A.; Hirte, H.W.; Bryson, P.; on behalf of the Gynecology Cancer Disease Site Group of Cancer Care Ontario’s Program in Evidence-Based Care. Optimal Chemotherapy Treatment for Women with Recurrent Ovarian Cancer. Curr. Oncol. 2007, 14, 195–208. https://doi.org/10.3747/co.2007.148. [CrossRef]

- Pignata, S.; Pisano, C.; Di Napoli, M.; Cecere, S.C.; Tambaro, R.; Attademo, L. Treatment of recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer 2019, 125 (Suppl. 24), 4609–4615. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.32500. Erratum in Cancer 2020, 126, 158. [CrossRef]

- Ledermann, J.A.; Raja, F.A.; Fotopoulou, C.; et. al., Newly Diagnosed and Relapsed Epithelial Ovarian Carcinoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow-Up, 2021, on Behalf of ESMO Working Group. Available online: https://www.esmo.org/guidelines/guidelines-by-topic/esmo-clinical-practice-guidelines-gynaecological-cancers/newly-diagnosed-and-relapsed-epithelial-ovarian-cancer/eupdate-newly-diagnosed-epithelial-ovarian-carcinoma-treatment-recommendations (accessed in 2021).

- Claussen, C.; Rody, A.; Hanker, L. Treatment of Recurrent Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. Geburtshilfe Und Frauenheilkd 2020, 80, 1195–1204. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-1128-0280. [CrossRef]

- Greening, S.; Sood, N.; Nicum, The challenges, and opportunities in ovarian cancer relapse: The role of second and third-line chemotherapy: Literature review. Gynecol. Pelvic Med. 2022, 5., pages 21-29, https://doi.org/10.21037/gpm-21-29. [CrossRef]

- Baert, T.; Ferrero, A.; Sehouli, J.; O’Donnell, D.; González-Martín, A.; Joly, F.; van der Velden, J.; Blecharz, P.; Tan, D.; Querleu, D.; et al. The systemic treatment of recurrent ovarian cancer revisited. Ann. Oncol. 2021, 32, 710–725. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2021.02.015. [CrossRef]

- Pfisterer, J.; Ledermann, J.A. Management of Platinum-Sensitive Recurrent Ovarian Cancer. Semin. Oncol. 2006, 33 (Suppl. 6), 12–16. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.seminoncol.2006.03.012. [CrossRef]

- Poveda, A.; Floquet, A.; Ledermann, J.A.; Asher, R.; Penson, R.T.; Oza, A.M.; Korach, J.; Huzarski, T.; Pignata, S.; Friedlander, M.; et al. Final overall survival (OS) results from SOLO2/ENGOT-ov21: A phase III trial assessing maintenance olaparib in patients (PTS) with platinum-sensitive, relapsed ovarian cancer and a BRCA mutation. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 6002.

- Mirza, M.R.; Monk, B.J.; Herrstedt, J.; Oza, A.M.; Mahner, S.; Redondo, A.; Fabbro, M.; Ledermann, J.A.; Lorusso, D.; Vergote, I.; et al. Niraparib Maintenance Therapy in Platinum-Sensitive, Recurrent Ovarian Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 2154–2164. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1611310. [CrossRef]

- Ledermann, J.A.; Harter, P.; Gourley, C.; Friedlander, M.; Vergote, I.; Rustin, G.; Scott, C.; Meier, W.; Shapira-Frommer, R.; Safra, T.; et al. Overall survival in patients with platinum-sensitive recurrent serous ovarian cancer receiving olaparib maintenance monotherapy: an updated analysis from a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17, 1579–1589. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(16)30376-x. [CrossRef]

- Pujade-Lauraine, E.; Ledermann, J.A.; Selle, F.; Gebski, V.; Penson, R.T.; Oza, A.M.; Korach, J.; Huzarski, T.; Poveda, A.; Pignata, S.; et al. Olaparib tablets as maintenance therapy in patients with platinum-sensitive, relapsed ovarian cancer and a BRCA1/2 mutation (SOLO2/ENGOT-Ov21): a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, 1274–12844. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30469-2. Erratum in Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, e510. [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.; Tinker, A.V.; Friedlander, M. “Platinum resistant” ovarian cancer: What is it, whom to treat and how to measure benefit? Gynecol. Oncol. 2014, 133, 624–631. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.02.038. [CrossRef]

- Wagner, U.; Marth, C.; Largillier, R.; Kaern, J.; Brown, C.; Heywood, M.; Bonaventura, T.; Vergote, I.; Piccirillo, M.C.; Fossati, R.; et al. Final overall survival results of phase III GCIG CALYPSO trial of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin and carboplatin vs paclitaxel and carboplatin in platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer patients. Br. J. Cancer 2012, 107, 588–591. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2012.307. [CrossRef]

- Van Zyl, B.; Tang, D.; Bowden, N.A. Biomarkers of platinum resistance in ovarian cancer: What can we use to improve treatment. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2018, 25, R303–R318. https://doi.org/10.1530/erc-17-0336. [CrossRef]

- Havasi, A.; Cainap, S.S.; Havasi, A.T.; Cainap, C. Ovarian Cancer—Insights into Platinum Resistance and Overcoming It. Medicina 2023, 59, 544. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59030544. [CrossRef]

- Tokunaga, H.; Shimada, M.; Ishikawa, M.; Yaegashi, N. TNM classification of gynecological malignant tumors, eighth edition: Changes between the seventh and eighth editions. Jpn J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 49, 311–320. https://doi.org/10.1093/jjco/hyy206. [CrossRef]

- American Cancer Society. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/ovarian-cancer/causes-risks-prevention/risk-factors.html (accessed on Jan 26, 2021).

- Meena, R.K.; Syed, N.A.; Sheikh, Z.A.; Guru, F.R.; Mir, M.H.; Banday, S.Z.; Mp, A.K.; Parveen, S.; Dar, N.A.; Bhat, G.M. Patterns of Treatment and Outcomes in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer: A Retrospective North Indian Single-Institution Experience. JCO Glob. Oncol. 2022, 8, e2200032. https://doi.org/10.1200/go.22.00032. [CrossRef]

- Ries, L.A. Ovarian cancer. Survival and treatment differences by age. Cancer 1993, 71 (Suppl. 2), 524–529. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.2820710206. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wu, M.; Wang, F. Research Progress in Prognostic Factors and Biomarkers of Ovarian Cancer. J. Cancer 2021, 12, 3976–3996. https://doi.org/10.7150/jca.47695. [CrossRef]

- Gadducci, A.; Fuso, L.; Cosio, S.; Landoni, F.; Maggino, T.; Perotto, S.; Sartori, E.; Testa, A.; Galletto, L.; Zola, P. Are Surveillance Procedures of Clinical Benefit for Patients Treated for Ovarian Cancer?: A Retrospective Italian Multicentric Study. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2009, 19, 367–374. https://doi.org/10.1111/igc.0b013e3181a1cc02. [CrossRef]

- Gronlund, B.; Høgdall, C.; Hansen, H.H.; Engelholm, S.A. Results of Reinduction Therapy with Paclitaxel and Carboplatin in Recurrent Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2001, 83, 128–134. https://doi.org/10.1006/gyno.2001.6364. [CrossRef]

- Sehouli, J.; Chekerov, R.; Reinthaller, A.; Richter, R.; Gonzalez-Martin, A.; Harter, P.; Woopen, H.; Petru, E.; Hanker, L.C.; Keil, E.; et al. Topotecan plus carboplatin versus standard therapy with paclitaxel plus carboplatin (PC) or gemcitabine plus carboplatin (GC) or pegylated liposomal doxorubicin plus carboplatin (PLDC): A randomized phase III trial of the NOGGO-AGO-Study Group-AGO Austria and GEICO-ENGOT-GCIG intergroup study (HECTOR). Ann. Oncol. 2016, 27, 2236–2241. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdw418. [CrossRef]

- Parmar, M.K.; Ledermann, J.A.; Colombo, N.; du Bois, A.; Delaloye, J.F.; Kristensen, G.B.; Wheeler, S.; Swart, A.M.; Qian, W.; Torri, V.; et al.; ICON and AGO Collaborators. Paclitaxel plus platinum-based chemotherapy versus conventional platinum-based chemotherapy in women with relapsed ovarian cancer: The ICON4/AGO-OVAR-2.2 trial. Lancet 2003, 361, 2099–2106. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(03)13718-x. [CrossRef]

- Pujade-Lauraine, E.; Hilpert, F.; Weber, B.; Reuss, A.; Poveda, A.; Kristensen, G.; Sorio, R.; Vergote, I.; Witteveen, P.; Bamias, A.; et al. Bevacizumab Combined With Chemotherapy for Platinum-Resistant Recurrent Ovarian Cancer: The AURELIA Open-Label Randomized Phase III Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 1302–1308. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2013.51.4489. Erratum in J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 4025. [CrossRef]

- McGuire, W.P.; Hoskins, W.J.; Brady, M.F.; Kucera, P.R.; Partridge, E.E.; Look, K.Y.; Clarke-Pearson, D.L.; Davidson, M. Cyclophosphamide and Cisplatin Compared with Paclitaxel and Cisplatin in Patients with Stage III and Stage IV Ovarian Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996, 334, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199601043340101. [CrossRef]

- Abudou, M.; Zhong, D.; Wu, T.; Wu, X. Topotecan for ovarian cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2008, 2020, CD005589. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd005589.pub2. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, D.; Shen, K.; Li, Q.; Zhang, G.; Wu, X.; Cui, M.; Yue, Y.; Cheng, W.; et al. Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer. J. Ovarian Res. 2021, 14, 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13048-020-00736-2. [CrossRef]

- Berg, T.; Nøttrup, T.J.; Roed, H. Gemcitabine for recurrent ovarian cancer—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gynecol. Oncol. 2019, 155, 530–537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2019.09.026. [CrossRef]

- Lindemann, K.; Gao, B.; Mapagu, C.; Fereday, S.; Emmanuel, C.; Alsop, K.; Traficante, N.; Harnett, P.R.; Bowtell, D.D.; Defazio, A. Response rates to second-line platinum-based therapy in ovarian cancer patients challenge the clinical definition of platinum resistance. Gynecol. Oncol. 2018, 150, 239–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2018.05.020. [CrossRef]

- Bedirian, K.; Aghabekyan, T.; Mesrobian, A.; Shekherdimian, S.; Zohrabyan, D.; Safaryan, L.; Sargsyan, L.; Avagyan, A.; Harutyunyan, L.; Voskanyan, A.; et al. Overview of Cancer Control in Armenia and Policy Implications. Front. Oncol. 2022, 11, 782581. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2021.782581. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions, and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions, or products referred to in the content. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).