Submitted:

05 January 2024

Posted:

08 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. US Poliovirus Containment Program

2.2. Facility Identification and Outreach

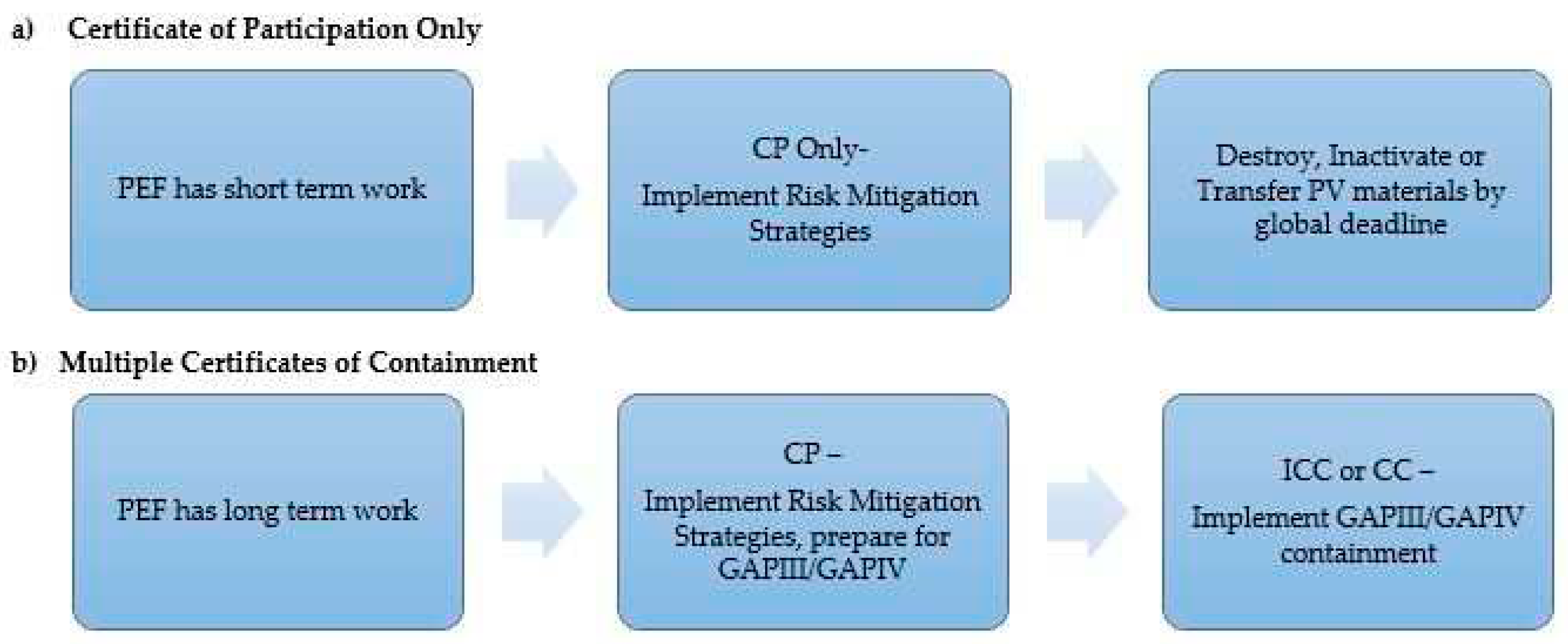

2.3. Certification Process

2.4. Site Visits

2.5. Information Collection and Analysis

3. Results

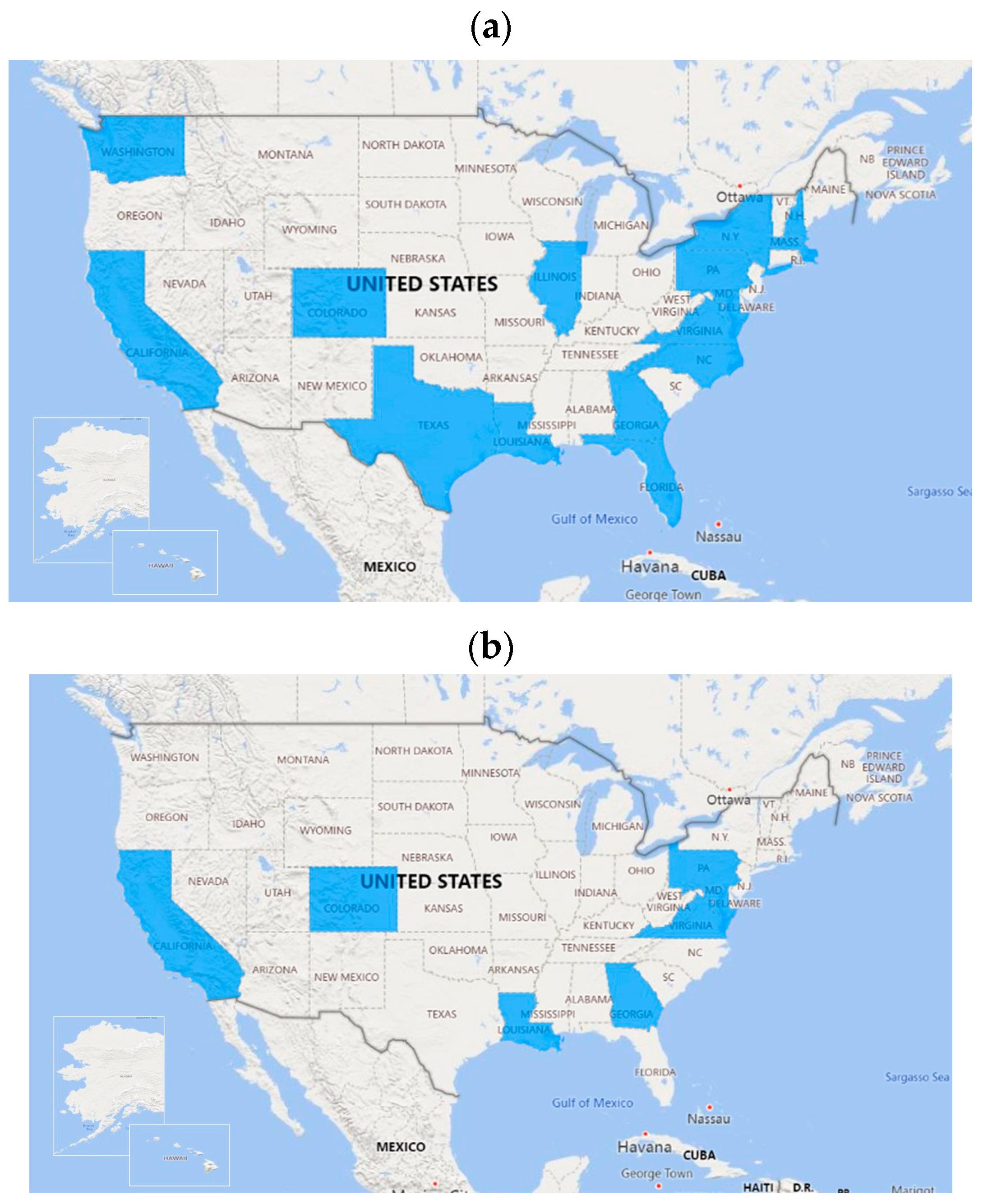

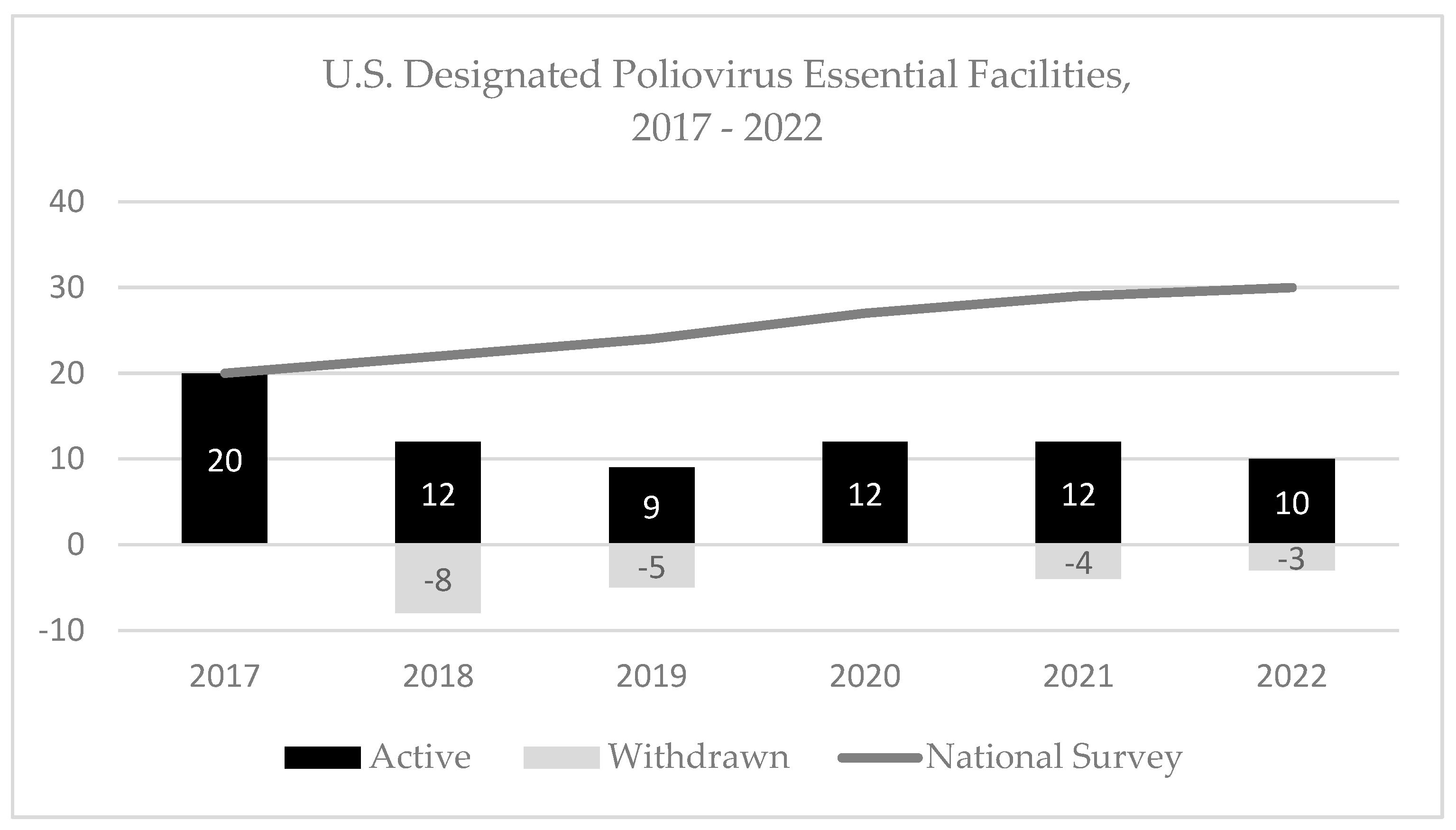

3.1. Facility Identification and Outreach

3.2. Certificate of Participation Application

3.3. Preliminary Containment Conditions – Risk Mitigation Strategies

3.4. Certification Process

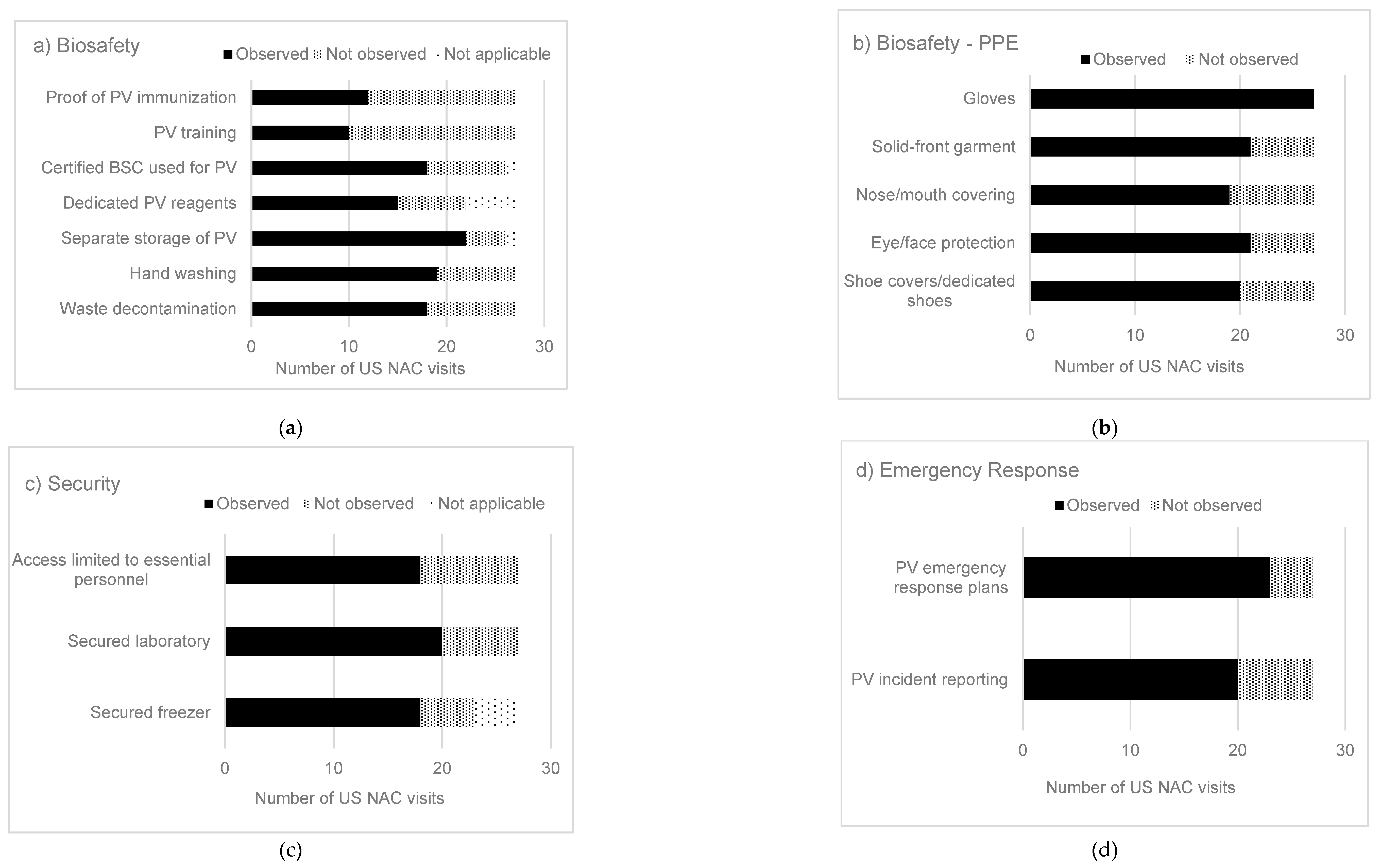

3.5. Site Visits

3.6. US NAC and GCC-Endorsement

3.7. Withdrawal of PEFs

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee SE, Greene SA, Burns CC, et al. Progress Toward Poliomyelitis Eradication - Worldwide, January 2021-March 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(19):517-522. PMID: 37167156; PMCID: PMC10208367. [CrossRef]

- Strebel PM, Sutter RW, Cochi SL, et al. Epidemiology of poliomyelitis in the United States one decade after the last reported case of indigenous wild virus-associated disease. Clin Infect Dis 1992;14:568--79. [CrossRef]

- Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Revised Recommendations for Routine Poliomyelitis Vaccination. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1999;48(27). [CrossRef]

- Moffett DB, Llewellyn A, Singh H, et al. Progress Toward Poliovirus Containment Implementation — Worldwide, 2019–2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1330–1333. [CrossRef]

- Moffett DB, Llewellyn A, Singh H, et al. Progress Toward Poliovirus Containment Implementation - Worldwide, 2018-2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(38):825-829. [CrossRef]

- Dowdle WR, Gary HE, Sanders R, van Loon AM. Can post-eradication laboratory containment of wild polioviruses be achieved? Bull World Health Organ. 2002;80(4):311-6.

- Bandyopadhyay AS, Singh H, Fournier-Caruana J et al. Facility-Associated Release of Polioviruses into Communities-Risks for the Post eradication Era. Emerg Infect Dis. 2019;25(7):1363-1369. [CrossRef]

- Duizer E, Ruijs WL, Putri Hintaran AD, et al. Wild poliovirus type 3 (WPV3)-shedding event following detection in environmental surveillance of poliovirus essential facilities, the Netherlands, November 2022 to January 2023. Euro Surveill. 2023; 28(5):2300049. PMID: 36729115; PMCID: PMC9896605. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO global action plan to minimize poliovirus facility-associated risk after type-specific eradication of wild polioviruses and sequential cessation of oral polio vaccine use—GAPIII. 3rd ed. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2015.

- World Health Organization. WHO Global Action Plan for Poliovirus Containment, Fourth edition (unedited version). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2022.

- Seventy first World Health Assembly. WHA Resolution 71.16: Poliomyelitis – containment of polioviruses. 2018. https://polioeradication.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/A71_R16-en.pdf Accessed on December 6, 2023.

- World Health Organization. Guidance to minimize risks for facilities collecting, handling or storing materials potentially infectious for polioviruses (PIM Guidance). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018.

- World Health Organization. Containment certification scheme to support the WHO global action plan for poliovirus containment (GAPIII-CCS). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2017.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National laboratory inventory for global poliovirus containment--United States, November 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53(21):457-9.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), United States National Authority for Containment. Past Poliovirus Surveys of U.S. Laboratories. https://www.cdc.gov/orr/polioviruscontainment/us-containment.htm. Accessed on December 6, 2023.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National Inventory for Poliovirus Containment: Minimizing Risk of Poliovirus Release from Laboratories in the United States. Federal Register. Notice 84(195):53731.

- US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). CDC. Biosafety in microbiological and biomedical laboratories, 5th ed. Atlanta, GA: CDC; 2009. HHS Publication no. (CDC) 21-1112.

- Global Polio Eradication Initiative. Polio Endgame Strategy 2022-2026: Delivering on a promise. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021.

- World Health Organization. Country progress towards poliovirus containment certification (website, data as of 20 November 2023). https://polioeradication.org/polio-today/preparing-for-a-polio-free-world/containment/. Accessed on December 6, 2023.

- U.S. Government Publishing Office. Electronic Code of Federal Regulations Title 42 Chapter 1 Subchapter F Part 73. https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-42/chapter-I/subchapter-F/part-73 . Accessed on December 6, 2023.

- Irwin A. Polio is on the brink of eradication. Here's how to keep it from coming back. Nature. 2023; 623(7988):680-682. PMID: 37989772. [CrossRef]

- Jeannoël M, Antona D, Lazarus C, Lina B, Schuffenecker I. Risk Assessment and Virological Monitoring Following an Accidental Exposure to Concentrated Sabin Poliovirus Type 3 in France, November 2018. Vaccines (Basel). 2020;8(2):331. [CrossRef]

- Duizer E, Ruijs WL, van der Weijden CP, Timen A. Response to a wild poliovirus type 2 (WPV2)-shedding event following accidental exposure to WPV2, the Netherlands, April 2017. Euro Surveill. 2017;22:30542. [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Polio vaccination coverage among children 19-35 months by State, HHS Region, and the United States, National Immunization Survey-Child (NIS-Child), 1995 through 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/imz-managers/coverage/childvaxview/interactive-reports/index. Accessed on December 6, 2023.

- World Health Organization. Immunization Data portal, Polio 3rd dose coverage estimates. https://immunizationdata.who.int/pages/profiles/usa.htmlAccessed on December 6, 2023.

- Ottendorfer C et al. Implementation of GAPIII Laboratory Containment in Poliovirus-Essential Facilities – United States, 2017-2023. Manuscript in draft.

| No. | Hazard Controla | Category | Risk Mitigation Strategy for Poliovirus Materialsb | Containment Strategies Observed by US NAC |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency/No. visits | Percent (%) |

||||

| 1 | Elimination | Biosafety | Destroy unneeded poliovirus materials | 20/27 | 74 |

| 2 | Elimination | Biosafety | Inactivation, fixation or extraction of poliovirus materials | 8/27 | 30 |

| 3 | Engineering | Biosafety | Dedicated room (e.g., an isolation room within a larger laboratory) used for poliovirus | 8/27 | 30 |

| 4 | Engineering | Biosafety | Two doors are present between public areas and the laboratory room | 25/27 | 93 |

| 5 | Engineering | Biosafety | Certified BSC used for poliovirus work | 18/27 | 67 |

| 6 | Engineering | Biosafety | Centrifuge safety cups/sealed rotors that are loaded and unloaded in a BSC for poliovirus work | 11/27 | 41 |

| 7 | Engineering | Biosafety | Containment caging system with HEPA filtered exhaust used for housing PV-infected animals | 2/13 | 15 |

| 8 | Administrative | Biosafety | Risk assessments for poliovirus containment | 9/13 | 69 |

| 9 | Administrative | Biosafety | Risk assessments for animal work | 2/13 | 15 |

| 10 | Administrative | Biosafety | PV work reviewed/approved by institutional committees (i.e., institutional biosafety committee (IBC), institutional animal care and use committee (IACUC)) | 4/13 | 31 |

| 11 | Administrative | Biosafety | Dedicated BSC and incubator used for poliovirus | 10/27 | 37 |

| 12 | Administrative | Biosafety | Dedicated caging system used for PV-inoculated animals | 1/13 | 8 |

| 13 | Administrative | Biosafety | Shared laboratory uses PV spatial and temporal separation with appropriate decontamination procedures | 9/27 | 33 |

| 14 | Administrative | Biosafety | Personnel trained in poliovirus biosafety and security practices | 10/27 | 37 |

| 15 | Administrative | Biosafety | Personnel receive annual refresher training | 5/13 | 38 |

| 16 | Administrative | Biosafety | Personnel provide proof of poliovirus immunization | 12/27 | 44 |

| 17 | Administrative | Biosafety | Personnel enrolled in occupational health program | 12/27 | 44 |

| 18 | Administrative | Biosafety | Personnel competent in good microbiological techniques | 17/27 | 63 |

| 19 | Administrative | Biosafety | Personnel wash hands prior to exit of the laboratory | 19/27 | 70 |

| 20 | Administrative | Biosafety | Protective clothing and gloves removed prior to exit from the laboratory | 16/27 | 59 |

| 21 | Administrative | Biosafety | Reusable PPE is decontaminated prior to storage and reuse | 12/27 | 44 |

| 22 | Administrative | Biosafety | Disposable PPE is treated as biohazardous waste | 22/27 | 81 |

| 23 | Administrative | Biosafety | Durable leak proof transport container used when poliovirus is removed from primary containment | 17/27 | 63 |

| 24 | Administrative | Biosafety | Dedicated reagents used for poliovirus | 15/27 | 55 |

| 25 | Administrative | Biosafety | Segregate poliovirus from all other materials (e.g., in own clearly labeled freezer box) | 22/27 | 81 |

| 26 | Administrative | Biosafety | Perform work with one poliovirus serotype at a time to minimize potential cross-contamination (when possible) | 6/13 | 46 |

| 27 | Administrative | Biosafety | Decontamination of work surfaces | 18/27 | 67 |

| 28 | Administrative | Biosafety | All materials leaving the laboratory are decontaminated using an appropriate method (autoclave, incinerator) | 18/27 | 67 |

| 29 | Administrative | Biosafety | Periodic validation of autoclave decontamination procedures | 21/27 | 78 |

| 30 | Administrative | Biosafety | Containers with poliovirus are surface disinfected prior to removal from the BSC | 13/27 | 48 |

| 31 | Administrative | Biosafety | Procedures for decontamination of equipment are implemented | 14/27 | 52 |

| 32 | Administrative | Biosafety | Chemical treatment known to inactivate poliovirus implemented | 7/27 | 26 |

| 33 | Administrative | Security | Locked freezer where poliovirus is stored (when stored outside a dedicated, secured laboratory) | 18/27 | 67 |

| 34 | Administrative | Security | Locked laboratory | 20/27 | 74 |

| 35 | Administrative | Security | Limit access to personnel identified as essential by the facility | 18/27 | 67 |

| 36 | Administrative | Security | Poliovirus inventory records are current, accurate and complete | 7/13 | 54 |

| 37 | Administrative | Security | Poliovirus animal tracking and infected tissue inventory records | 1/13 | 8 |

| 38 | Administrative | Security | Security policies implemented for controlled access to poliovirus materials and areas | 9/13 | 69 |

| 39 | Administrative | Security | Individual entries into poliovirus areas are documented (e.g., electronic record, manual logbooks) | 8/13 | 61 |

| 40 | Administrative | Security | Visitor policy for entering poliovirus areas | 6/13 | 46 |

| 41 | Administrative | Emergency Response | Emergency response plans developed, including measures to protect personnel and the environment in the event of a releasec | 23/27 | 85 |

| 42 | Administrative | Emergency Response | Personnel report accidents or incidents with PV per institutional policy | 20/27 | 74 |

| 43 | Administrative | Emergency Response | Notify appropriate state and local agencies of possession of PV materials | 8/13 | 61 |

| 44 | Administrative | Emergency Response | Develop and coordinate emergency response plans with first responders | 7/13 | 54 |

| 45 | Administrative | Emergency Response | Develop response procedures for PV-infected escaped animals | 1/13 | 8 |

| 46 | PPEd | Biosafety | Protective laboratory clothing with a solid-front (e.g., disposable wrap-around gown, scrubs, coverall) | 21/27 | 78 |

| 47 | PPE | Biosafety | Gloves (double gloves are recommended) | 27/27 | 100 |

| 48 | PPE | Biosafety | Face or surgical mask or respirator | 19/27 | 70 |

| 49 | PPE | Biosafety | Eye and face protection for anticipated splashes or sprays (e.g., safety glasses, face shield) | 21/27 | 78 |

| 50 | PPE | Biosafety | Shoe covers or dedicated shoes | 20/27 | 74 |

| CCSa Process | PEF Participation in Certification | Frequency (N=30) | Percent (%) | Time (days) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Range | ||||

| Option A | Facility submits CP application | 20 | 67 | - | - |

| USA requirement | i. Implement risk mitigation strategies | 18/20 | 90 | 83 | 3-418 |

| Step 1 | ii. NAC endorsement | 17/20 | 85 | 84 | 3-418 |

| Step 2 | iii. WHO review | 17/20 | 85 | 10 | 1-128 |

| Step 3 | iv. GCC-CWG review | 17/20 | 85 | 22 | 1-77 |

| Step 4 | v. GCC endorsementb | 16/20 | 80 | 12.5 | 1-463 |

| Step 5 | vi. CP issuedc | 15/20 | 75 | 233 | 91-678 |

| Step 6 | vii. Facility withdraws from certificationd | ||||

| - | • before US NAC endorsement | 3/20 | 15 | 39 | 38-373 |

| - | • before GCC endorsement | 1/20 | 5 | 608 | - |

| - | • ends work under valid CP | 6/20 | 30 | 841.5 | 151-1471 |

| Option B | No participation, destroy or transfer PV | 10 | 33 | - | - |

| PEF Characteristicsa | 27 Laboratory Featuresb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=18 PEFs | Frequency (N=18) |

Percent (%) |

PV Laboratory Sites (operated in 18 PEFs) | Frequency (n= 20) |

Percent (%) |

| Facility primary work objective | Containment boundary | ||||

| Biomedical research | 9 | 50 | Containment perimeter sealable for gaseous decontamination | 5 | 25 |

| Clinical diagnostic laboratory | 1 | 6 | Facility is equipped with a double-door personnel airlock/anteroom | 7 | 35 |

| Public health laboratory | 4 | 22 | Double doors are interlocked (physical or procedural) | 5 | 25 |

| Industrial/production laboratory | 2 | 11 | Backflow prevention on all services/ utilities passing across the boundary | 2 | 10 |

| Other | 2 | 11 | Sinks and Showers | ||

| Virus typec | Hands-free/automated hand washing sink | 8 | 40 | ||

| WPV2/VDPV2 | 9 | 50 | Personal exit shower | 4 | 20 |

| WPV3/VDPV3 | 6 | 33 | Personal walk-through exit shower | 2 | 10 |

| OPV/Sabin 2 | 12 | 67 | Emergency shower | 16 | 80 |

| nOPV2 | 6 | 33 | Ventilation System | ||

| Work type(s)d | Controlled air system maintains inward directional airflow | 11 | 55 | ||

| Research | 12 | 67 | Exhaust air is HEPA filtered | 7 | 35 |

| Vaccine production | 0 | 0 | Dedicated ventilation system to PV area (exhaust and supply) | 2 | 10 |

| Clinical trials | 3 | 17 | Backflow protection on supply air | 4 | 20 |

| Animal model | 4 | 22 | Ductwork sealable for gaseous decontamination | 4 | 20 |

| Diagnostics | 3 | 17 | Monitors/alarms to ensure directional airflow can be readily validated | 5 | 25 |

| QC testinge | 3 | 17 | Decontamination Systems | ||

| Storage only | 3 | 17 | Single door autoclave | 7 | 35 |

| Certification goalf | Pass-through autoclave | 5 | 25 | ||

| Certificate of Participation (CP) | 12 | 67 | Material airlock/decontamination chamber sealable for gaseous decontamination | 1 | 5 |

| Interim Certificate of Containment (ICC) | 1 | 5 | Dunk tank containing sufficient active compound to inactivate poliovirus | 1 | 5 |

| Certificate of Containment (CC) | 5 | 28 | Effluent decontamination system | 1 | 5 |

| Security | |||||

| Entry door(s) equipped with lock/lock cylinder rated as burglary resistant | 17 | 85 | |||

| Laboratory Design | Frequency (n = 20) |

Percent (%) | Lock(s) fail secure and allow egress only | 11 | 55 |

| Designg | Locked door with two-factor access control measure | 6 | 30 | ||

| A/BSL-3 | 4 | 20 | Video surveillance | 13 | 65 |

| A/BSL-2 | 13 | 65 | Two-person system for PV work | 7 | 35 |

| Storage only | 3 | 15 | Intrusion detection system | 8 | 40 |

| Facility perimeter is subject to constant monitoring | 13 | 65 | |||

| Facility is located on a secure site with perimeter control | 9 | 45 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).