1. Introduction

Burning mouth syndrome (BMS) is defined in the International Classification of Orofacial Pain, 2020 as “idiopathic orofacial pain with intraoral burning or dysesthesia recurring daily for more than 2 hours per day and more than 3 months, without any identifiable causative lesions, with or without somatosensory changes” [

1,

2]. The development of research diagnostic criteria for burning mouth syndrome was published in 2021 [

3]. Previously, it was divided into primary and secondary [

3]. Intraoral burning is a result of a range of underlying causes of lesions, such as candida infection, oral lichen planus, hyposalivation, contact mucosal reactivity, medications, anemia, deficiencies in vitamin B12 or folic acid, Sjögren's syndrome, diabetes, and hypothyroidism [

3]. However, the correct diagnosis of BMS is a diagnosis of exclusion, and only primary cases are diagnosed as true BMS. It is impossible to exclude all factors, even with blood tests, fungal culture tests, and thorough medical interviews. In our hospital, it is common to diagnose BMS by excluding other diseases whenever possible.

There are several effective methods for treating BMS patients. One of the treatment options for BMS is topical and systemic application of clonazepam [

4,

5]. For temporary treatment, there are a variety of options available such as systemic the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), zinc replacement therapy, alpha-lipoic acid, and aloe vera, hormone replacement therapy, cognitive behavior therapy, and acupuncture [

4,

5]. There is still a lack of understanding of their mechanisms in basic research [

4]. Moreover, there were not significant differences observed between the placebo and melatonin group and the placebo and clonazepam group considering multiplicity, regarding the difference in reduction of burning sensation between groups [

5]. Some suggest that cautious use of clonazepam and alpha-lipoid acid be used in the treatment of burning mouth syndrome [

6]. In summary, there is not qualitatively or quantitatively proven treatment for BMS.

Rikkosan is a traditional Japanese (kampo) medicine used to control oral pain [

7,

8]. Rikkosan has anti-inflammatory effects, but the exact mechanism is still unknown [

7,

8]. The surface anesthetic action of saishin, one of the components of rikkosan, may reduce the pain [

7,

8]. In addition, rikkosan conteins two ingredients with analgesic effect (ryutan: glycyrrhiza and kanzou: Japanese gentian) [

7].

Therefore, in this study, our aim was to verify the quantitative therapeutic effects of rikkosan. The quantitative effect hypothesis was based on our previous preliminary research [

9].

2. Materials and Methods

Diagnostic algorithm

Patients suspected of BMS were examined and diagnosed in our department according to the criteria of The International Classification of Orofacial Pain, 1st edition (ICOP) [

2,

3]. Patients were considered to have secondary BMS if systemic and psychosocial factors associated with secondary BMS and structural disorder in the oral cavity were found during examination. Patients with residual symptoms after antifungal therapy and replacement therapy for deficiency factors such as trace metals and vitamin B12 were diagnosed as BMS when blood tests were normal. In Japan, oral medicine has been established as a subspecialty of oral surgery. At our facility, multiple oral medicine and oral surgeons specialists with over 10 years of experience and accredited by the Japanese Society of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons make final diagnoses and provide treatment.

This retrospective study was conducted with the approval of the Hokkaido University Hospital Independent Clinical Research Review Committee (Approval No. 023-0331).

Patients

The data of 20 patients who were suspected to have primary or secondary BMS were reviewed at the Department of Oral Medicine, Hokkaido University Hospital between August 2019 and March 2023. Patients with an underlying medical condition, based on an interview, or any abnormalities found through our diagnostic algorithm were diagnosed secondary BMS. The classification of secondary BMS details was based on the one proposed by Currie et al.[

3] Twenty probable primary BMS patients who had clear medical records of their treatment were enrolled in this study. They were all women and treated with single agent rikkosan (2.5 g rikkosan [Tsumura, Tokyo, Japan]) three times daily (7.5 g/day).

Treatment algorithm for BMS

First, an explanation about BMS will be given. Subsequently, drug therapy is started according to the patient's preference, and follow-up visits are conducted once or twice a month. In our department, medications containing analgesic components are often indicated, however, anxiolytics and antidepressants may be ultimately selected for treatment based on the patient’s preference.

Study variables

Various factors, such as patient characteristics (age, sex) and clinical parameters (dosing period, treatment outcome, and side effects), were retrospectively examined.

The effectiveness of the treatment was assessed by referring to changes in NRS or VAS/10 scores. NRS or VAS/10 scores were evaluated by asking patients to assess the degree of pain they were currently experiencing, with 0 being no pain and 10 or 100 being the worst possible pain. NRS or VAS/10 scores were measured at the time of the initiation of rikkosan and at 1 month after.

Statistical analysis

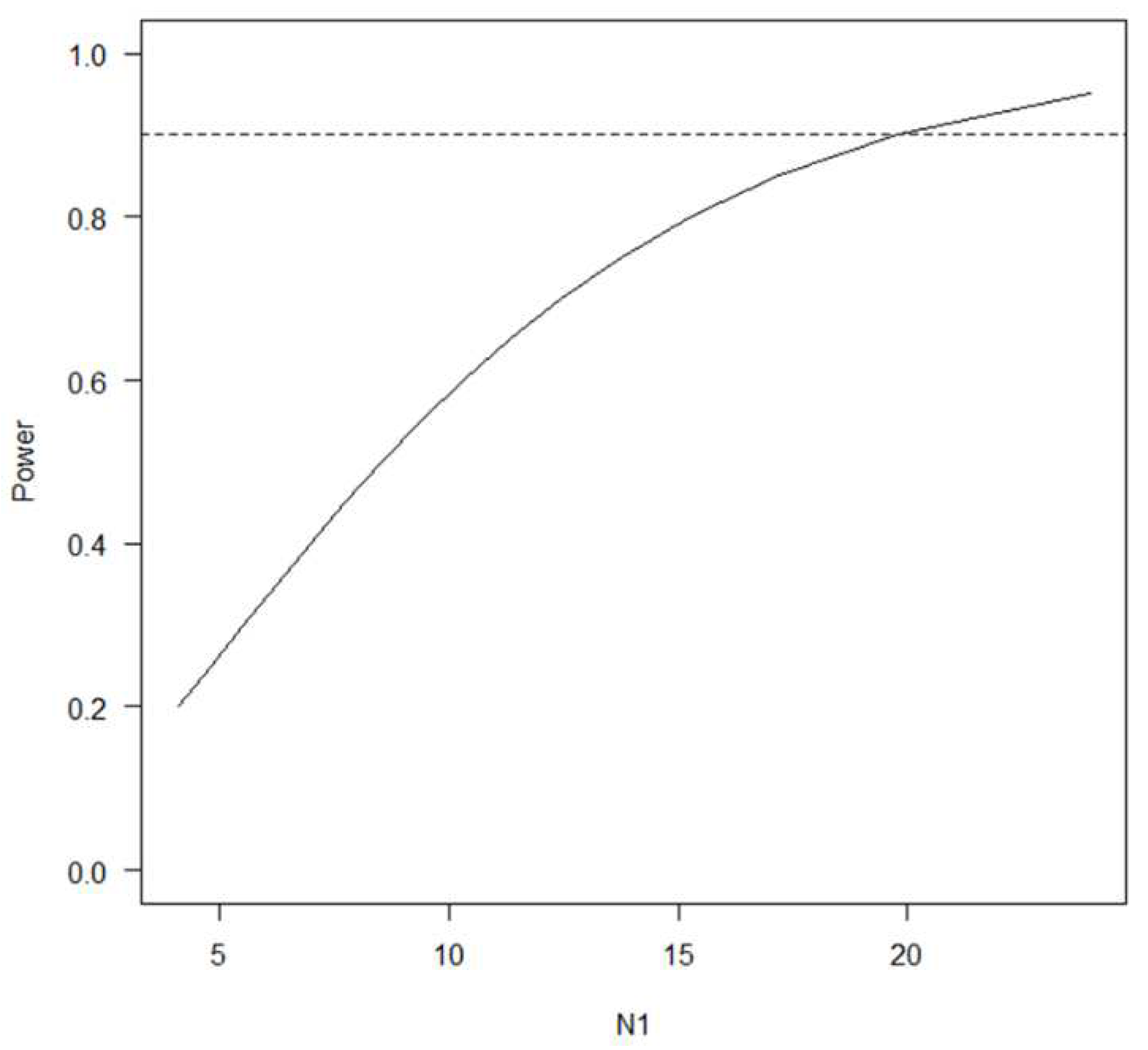

Statistical analyses were performed using Excel (Microsoft® Excel® for Microsoft 365MSO(version 2306 build 16.0.16529.20164, 64 bit) and R version 4.0.3 (2020-10-10) (Copyright © 2020, The R Foundation for Statistical Computing). The ceiling effect was determined when the mean plus exceeded the maximum value of the measurement, and the floor effect was determined when the mean minus one standard deviation (SD) exceeded the minimum value of the measurement. In chronic pain, improvement of NRS two level may lead to patient satisfaction. Therefore, the average effect of rikkosan was estimated to be a two-level reduction in NRS, and the sample size was designed with a standard deviation of 2.6, alpha error of 5%, and power of 90%. A paired t test was performed to assess significant differences in mean NRS scores at approximately a one-month interval.

3. Results

The calculated sample size was 20 people (

Figure 1). The patients were 43–80 (63.3 ± 13.4) years old and treated approximately 4 weeks (29.5 ± 6.5 days) for the initial treatment. No serious side effects were observed.

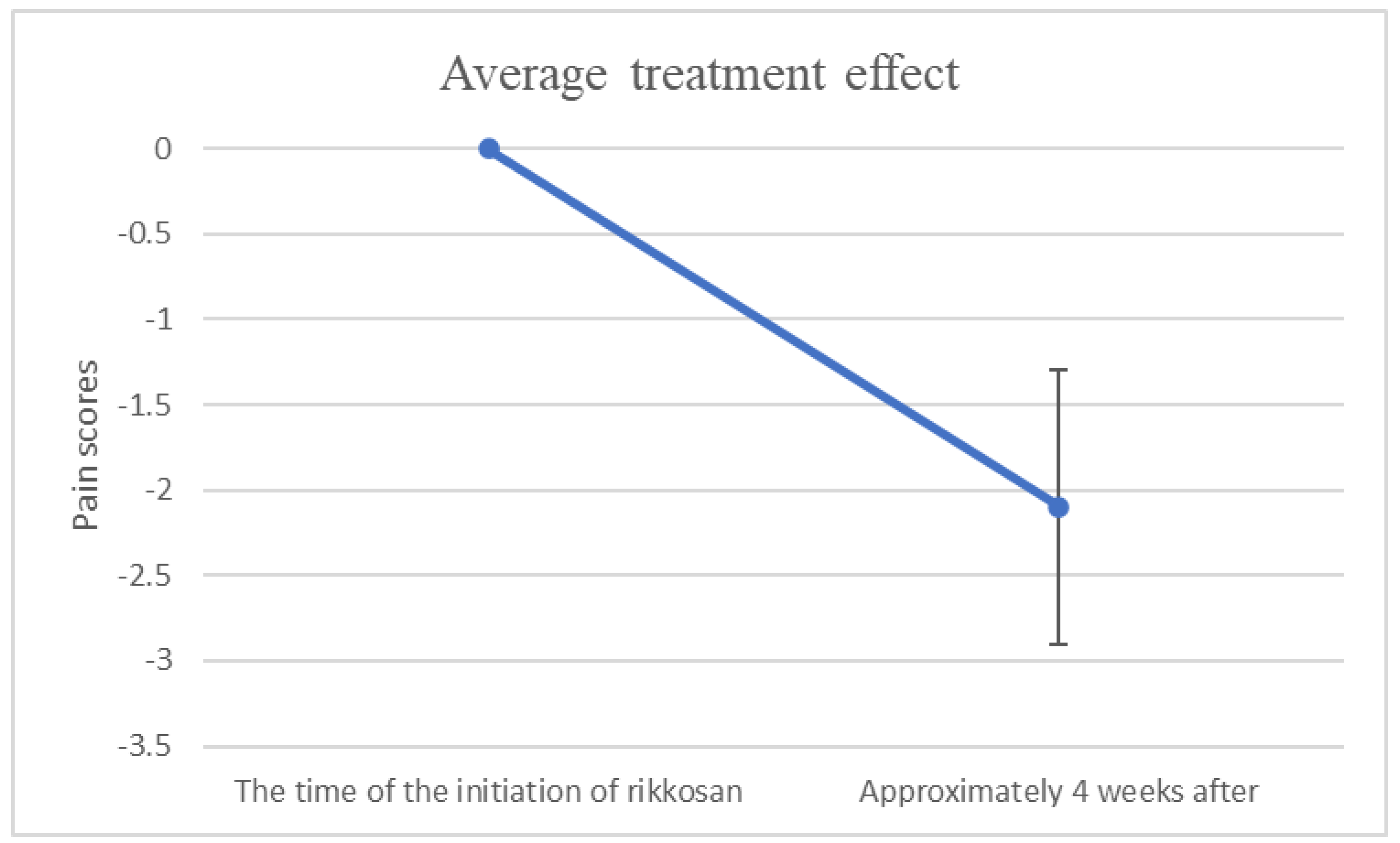

Figure 2 showed that changes in NRS or VAS/10 scores between the time of the initiation of rikkosan and one month after. As summarized in

Table 1, the ceiling effect and the floor effect were not observed. The assessment of pain was worked well. As summarized in

Table 2, the changes in pain scores for average treatment effect treated with rikkosan in 4 weeks. A significant difference was observed in pain evaluation before and after treatment (

p < 0.05).

4. Discussion

This is the first study to assess the effectiveness of rikkosan for BMS. Rikkosan treatment showed two-level reduction in NRS or VAS/10 scores for BMS and did not show any serious side effects. These results indicated that rikkosan could be a first good therapeutic option for BMS in the short term. Despite failing in clinical trials, one study concluded that melatonin and clonazepam were effective for BMS [

5]. Our results showed a larger change than the placebo in the previous study [

5] and, rikkosan produced a change in the pain score that was close to the amount that they concluded would be effective.

The response rate may be used to indicate the therapeutic effect. However, this does not depend on how effective they are individually, but rather they are the same if they are effective above a certain level. When the improvement rate is used as an evaluation index, there is a problem with the cutoff value. In this study, 85% improvement rate is achievable if a slight improvement is set as a cutoff. However, if the cutoff is an improvement of 2 or more, it is 50% in this study. In summary, this is a qualitative assessment.

On the other hand, this study performed quantitative evaluation using NRS or VAS. Consequently, the average treatment effect could be predicted. Due to the study design, 90% reproducibility is expected under similar conditions. Since no improvement can be expected without treatment, an average decrease in NRS of 2 levels may have medical significance. Conclusive criteria for conclusion of essential BMS have not however been standardized, the definition utilized in this study may differ from that utilized in another.

There are three pain classifications for chronic pain [

10]. There is a theory that BMS is neuropathic pain, but the evidence for this is unreliable [

11]. The reason for this is that the average age of the control and BMS patient groups differed by 22 years, and age-related neurodegeneration was not considered [

11]. If BMS is neuropathic pain, treatments for neuropathic pain should be effective, but there are almost no clinical trials. Nociceptive pain often involves obvious damage, which is easy to see on the body surface. BMS does not show obvious damage, so it is unlikely to be nociceptive pain, but the possibility of nociplastic pain that develops afterwards cannot be ruled out. BMS is probably nociplastic pain. There is no established treatment for nociplastic pain. The results of this study suggest that rikkosan is a candidate drug for the treatment of nociplastic pain or BMS.

Traditional Chinese medicine developed the use of medicinal plants [

12]. Traditional Japanese medicine, also called Kampo medicine, derives from traditional Chinese medicine [

12]. In recent years, kampo medicine has been attracting attention in the West as well [

12]. Rikkosan contains licorice. Licorice contains glycyrrhizic acid, which is hydrolyzed to glycyrrhetinic acid (GRA) in the intestine [

13]. Therefore, a side effect of rikkosan is pseudoaldosteronism, so regular blood tests are required. Electropharmacological profile of licorice can be explained by Na

+, Ca

2+ and K

+ channels blockade. Ion channels exist in pain receptors [

13]. These ion channels may be one of the targets of rikkosan.

This study has several limitations. This study was a single-arm study. A single-arm study is prone to bias and false positives, so a comparative study with a control group is preferable. Although this was a single-arm study, it is rare for the BMS patients to improve without doing anything. Even if the pain level decreases due to the placebo effect or the Hawthorne effect, it is still beneficial as a treatment. Rikkosan has a bitter taste, so some people don't like it. Taste preferences may be used to determine responders. Some patients did not want further treatment, but others still required treatment. The duration of treatment effects may vary depending on the patients. Therefore, further research on additional treatments is needed.

5. Conclusions

The results of our study suggest that rikkosan, a Japanese traditional Kampo medicine, can reduce two-level in NRS of patients with BMS. Rikkosan will have excellent effects in the short term.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Table S1: Pain scores data. Excel File: Our calculation processes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.I., K.N. and K.-i.S.; methodology, T.I. and K.N.; software, T.I.; validation, T.I., J.S., and Y.K.; formal analysis, T.I. and T.S.; investigation, T.I., T.T.; resources, T.I.; data curation, T.I.; writing—original draft preparation, T.I. and K.N.; writing—review and editing, T.I., K.-i.S., J.S. and Y.K.; visualization, T.I. and Y.N.; supervision, K.-i.S., and Y.K.; project administration, T.T. and K.-i.S.; funding acquisition, K.-i.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This retrospective study was conducted with the approval of the Hokkaido University Hospital Independent Clinical Research Review Committee (Approval No. 023-0331). All the study procedures were performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

This article does not disclose identifiable information of any of the participants in any form. Hence, consent for publication is not applicable in this case.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Russo, M.; Crafa, P.; Guglielmetti, S.; Franzoni, L.; Fiore, W.; Di Mario, F. Burning Mouth Syndrome Etiology: A Narrative Review. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis 2022, 31, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Classification of Orofacial Pain, 1st edition (ICOP). Cephalalgia 2020, 40, 129–221. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Currie, C.C.; Ohrbach, R.; De Leeuw, R.; Forssell, H.; Imamura, Y.; Jääskeläinen, S.K.; Koutris, M.; Nasri-Heir, C.; Huann, T.; Renton, T.; et al. Developing a research diagnostic criteria for burning mouth syndrome: Results from an international Delphi process. J Oral Rehabil 2021, 48, 308–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imamura, Y.; Okada-Ogawa, A.; Noma, N.; Shinozaki, T.; Watanabe, K.; Kohashi, R.; Shinoda, M.; Wada, A.; Abe, O.; Iwata, K. A perspective from experimental studies of burning mouth syndrome. Journal of Oral Science 2020, 62, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillo-Felipe, C.; Tvarijonaviciute, A.; López-Arjona, M.; Pardo-Marin, L.; Pons-Fuster, E.; López-Jornet, P. Response to Treatment with Melatonin and Clonazepam versus Placebo in Patients with Burning Mouth Syndrome. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suga, T.; Tu, T.T.H.; Nagamine, T.; Toyofuku, A. Careful use of clonazepam and alpha lipoid acid in burning mouth syndrome treatment. Oral Dis 2022, 28, 846–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakata, K.-i.; Yamazaki, Y.; Ohga, N.; Sato, J.; Asaka, T.; Yoshikawa, K.; Nakazawa, S.; Sato, C.; Nakamura, Y.; Kitagawa, Y. Clinical efficacy of a traditional Japanese (kampo) medicine for burning mouth syndrome. Traditional & Kampo Medicine 2016, 3, 120–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakazawa, S.; Okada, K.; Matsushita, T.; Hegozaki, S.; Sakata, K.-i.; Kitagawa, Y.; Yamazaki, Y. Effectiveness of rikkosan gargling for burning mouth syndrome. Traditional & Kampo Medicine 2017, 4, 121–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hato, H.; Sakata, K.-i.; Sato, J.; Asaka, T.; Ohga, N.; Yamazaki, Y.; Kitagawa, Y. Efficacy of rikkosan for primary burning mouth syndrome: a retrospective study. BioPsychoSocial Medicine 2021, 15, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nijs, J.; Lahousse, A.; Kapreli, E.; Bilika, P.; Saraçoğlu, İ.; Malfliet, A.; Coppieters, I.; De Baets, L.; Leysen, L.; Roose, E.; et al. Nociplastic Pain Criteria or Recognition of Central Sensitization? Pain Phenotyping in the Past, Present and Future. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, Z.; Renton, T.; Yiangou, Y.; Zakrzewska, J.; Chessell, I.P.; Bountra, C.; Anand, P. Burning mouth syndrome as a trigeminal small fibre neuropathy: Increased heat and capsaicin receptor TRPV1 in nerve fibres correlates with pain score. J Clin Neurosci 2007, 14, 864–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veilleux, M.-P.; Moriyama, S.; Yoshioka, M.; Hinode, D.; Grenier, D. A Review of Evidence for a Therapeutic Application of Traditional Japanese Kampo Medicine for Oral Diseases/Disorders. Medicines 2018, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izumi-Nakaseko, H.; Chiba, K.; Goto, A.; Kambayashi, R.; Matsumoto, A.; Takei, Y.; Kawai, S.; Sugiyama, A. Electropharmacological Characterization of Licorice Using the Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Cardiomyocytes Sheets and the Chronic Atrioventricular Block Dogs. Cardiovascular Toxicology 2023, 23, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).