Submitted:

08 January 2024

Posted:

09 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

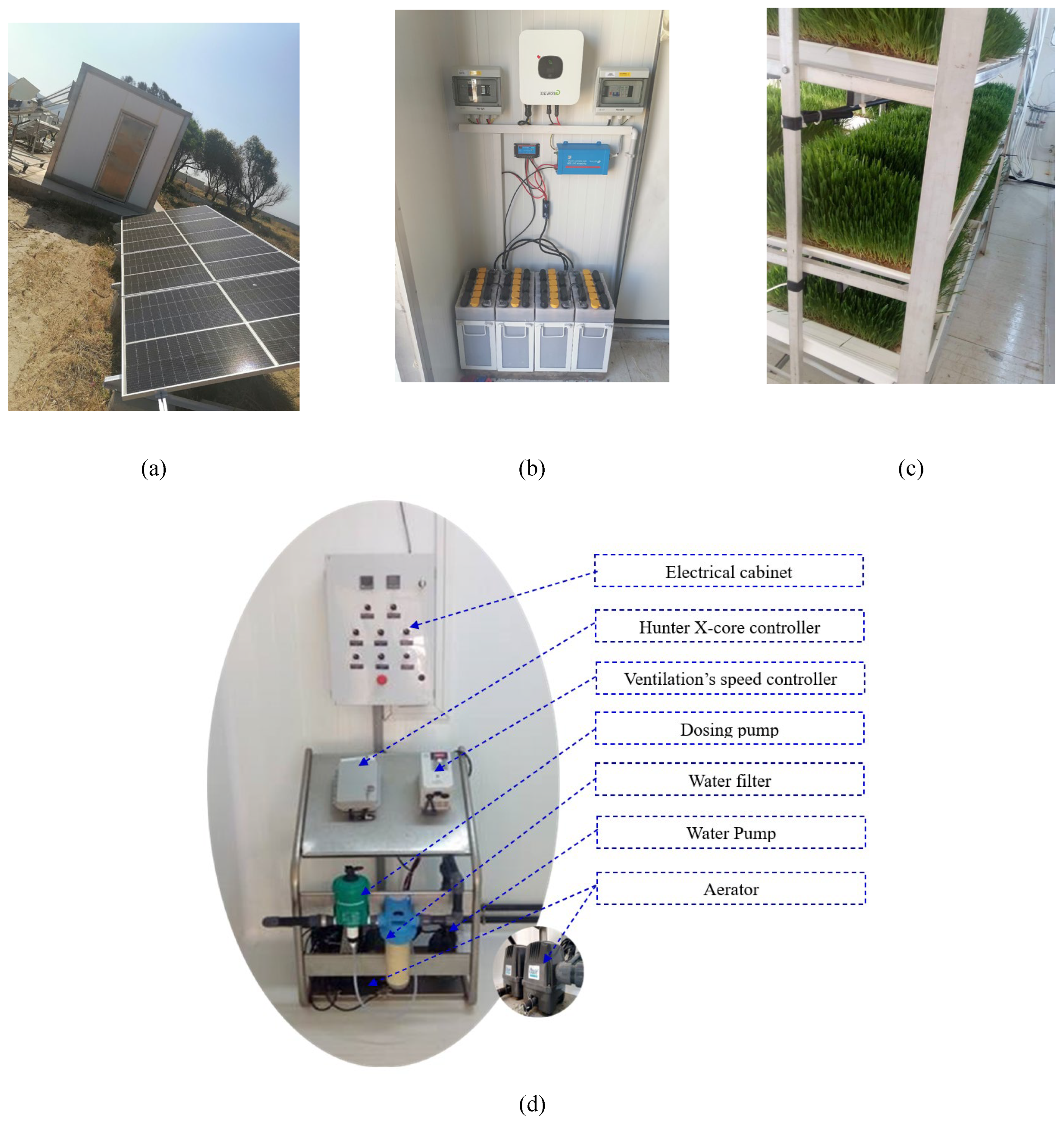

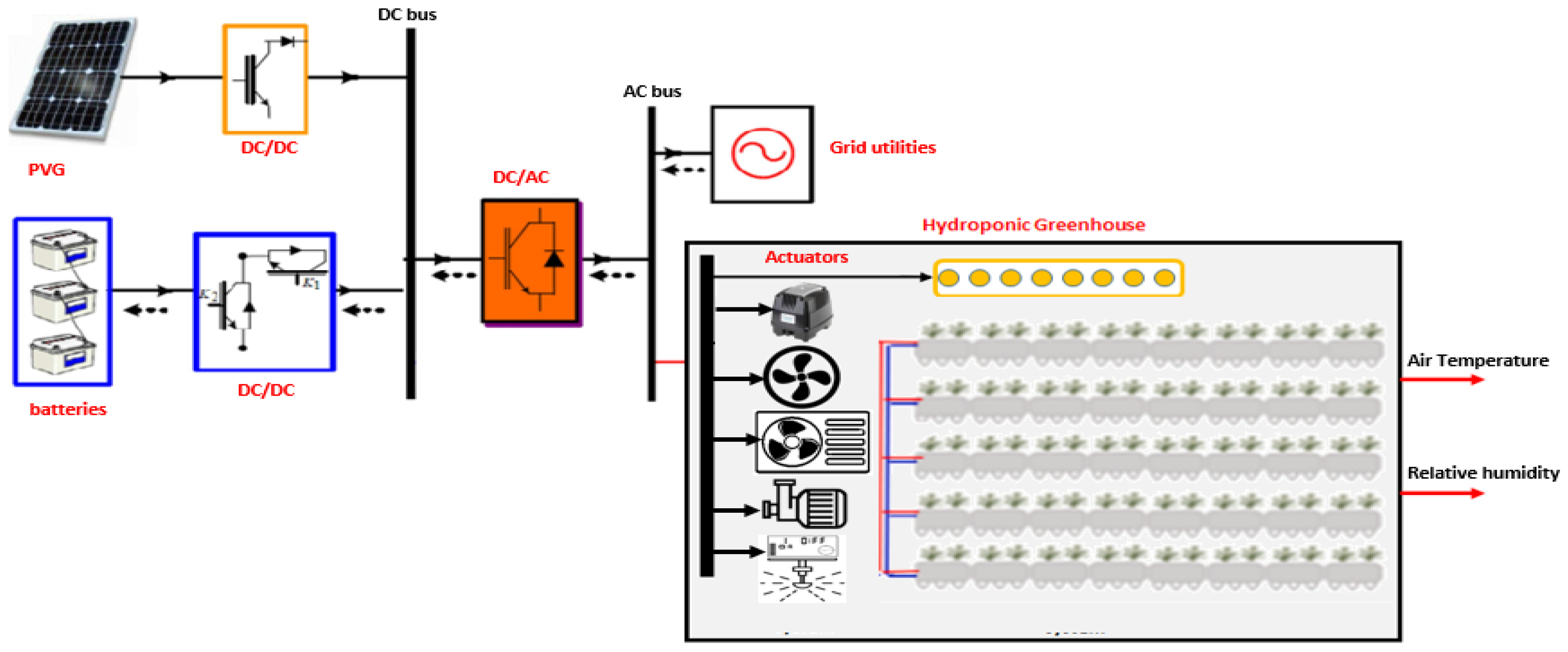

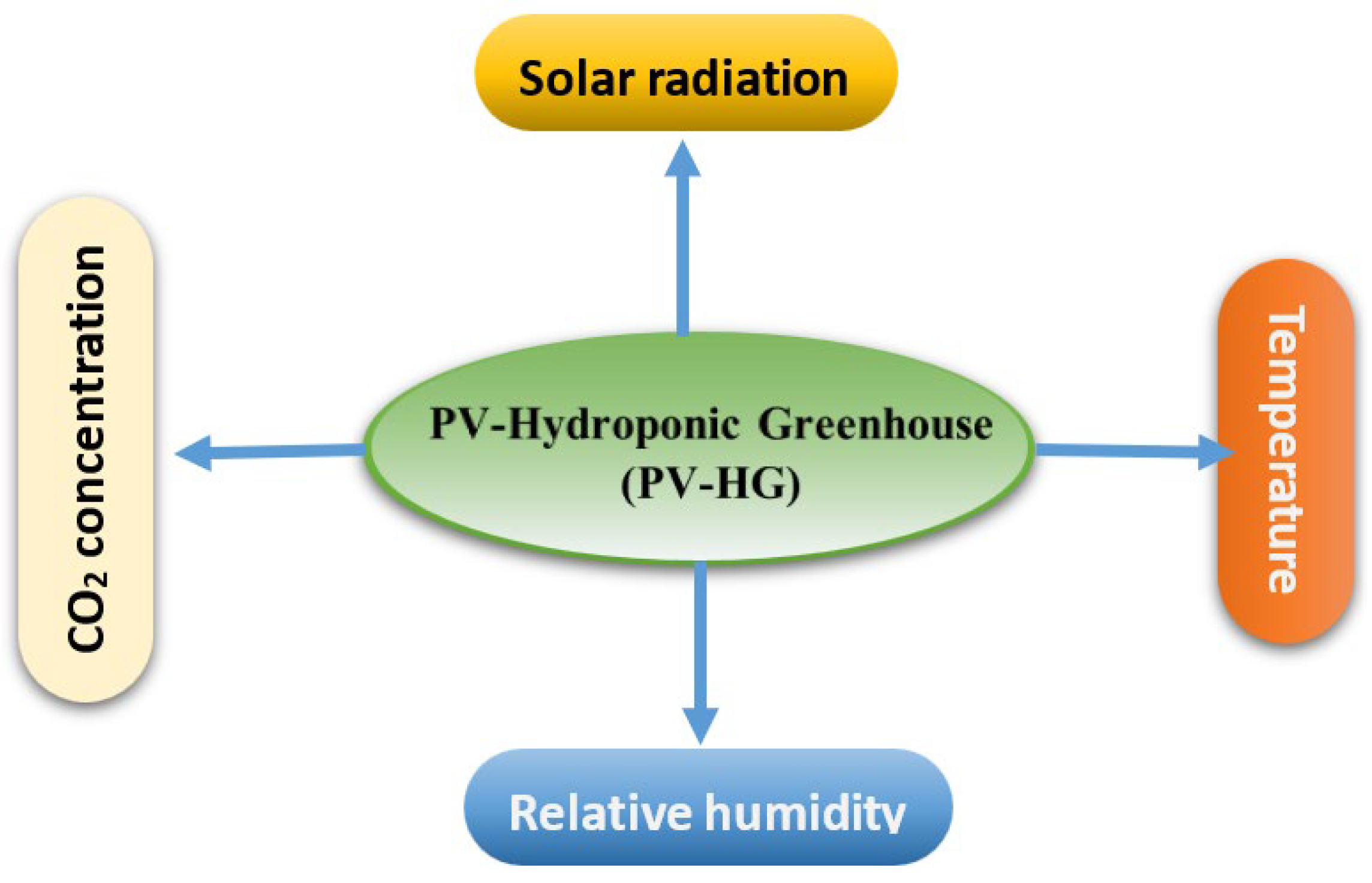

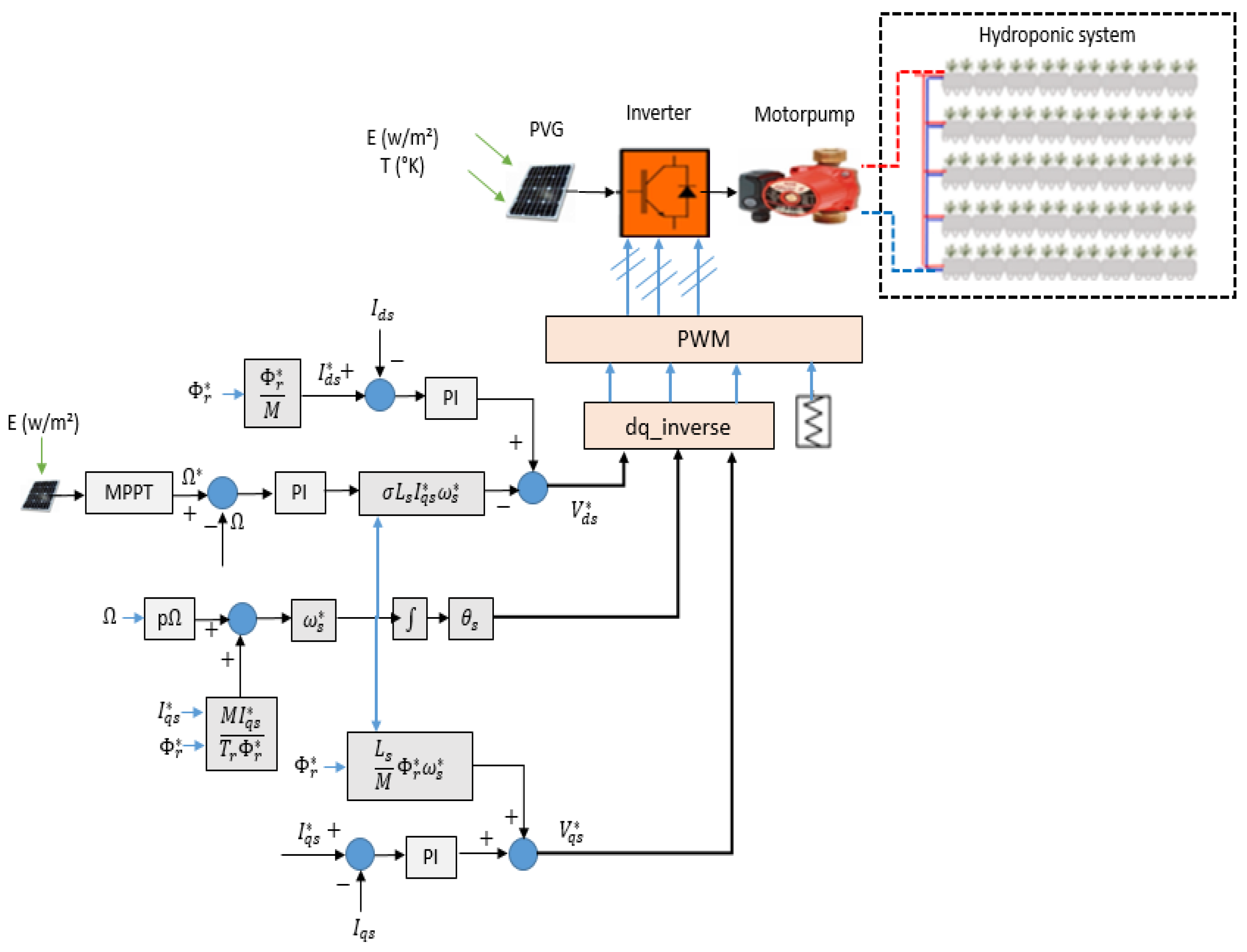

2.1. Description of the PV Hydroponic Greenhouse (PV-HG)

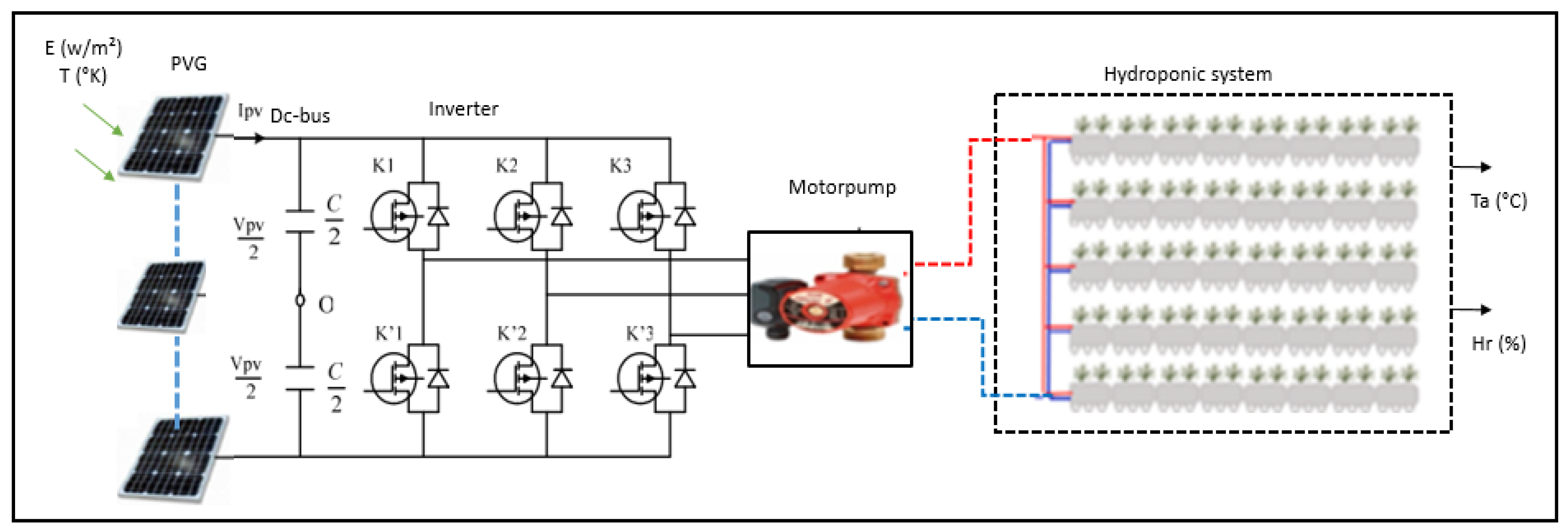

2.2. Modeling of the Stand-alone PV-HG

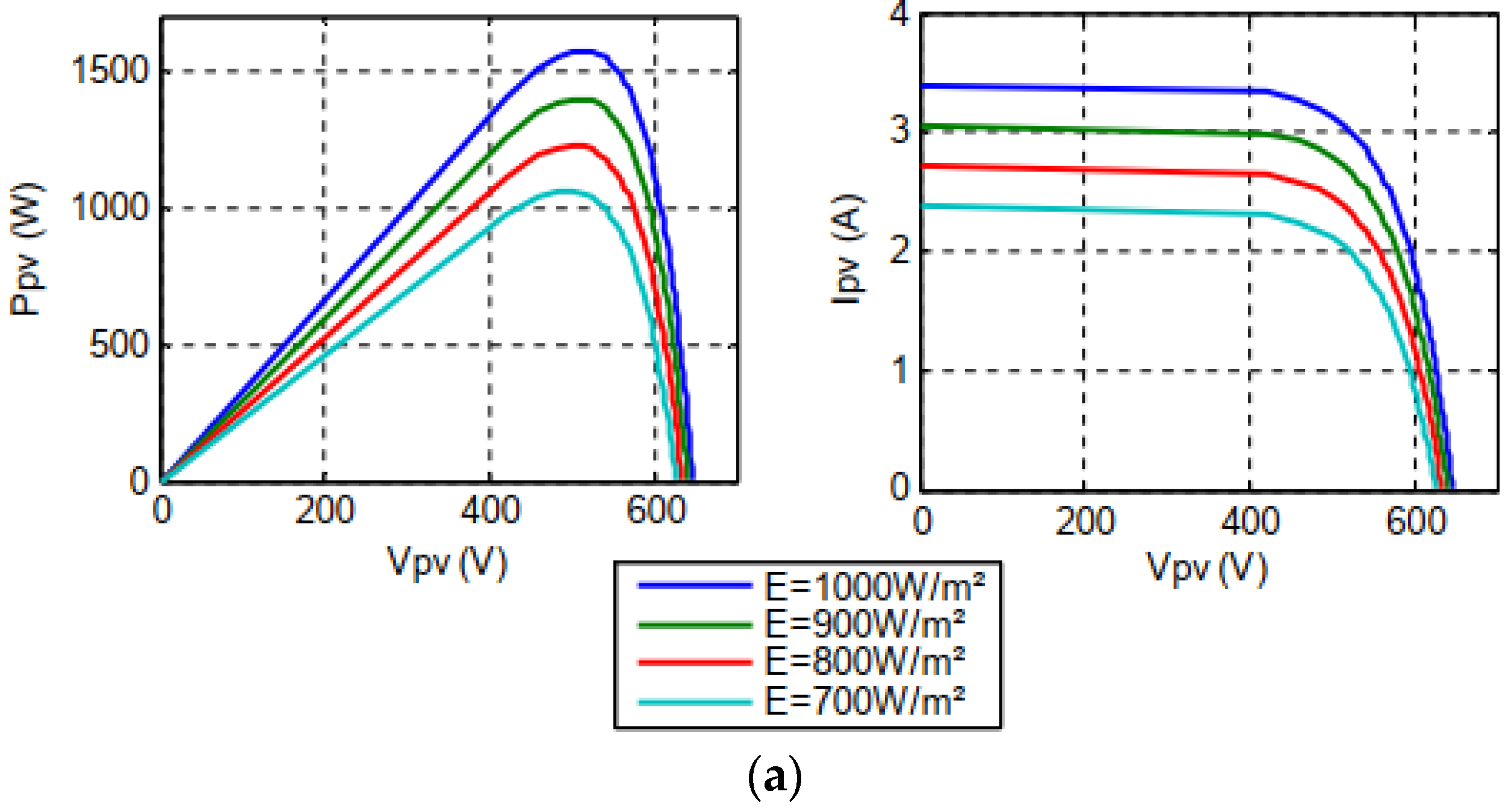

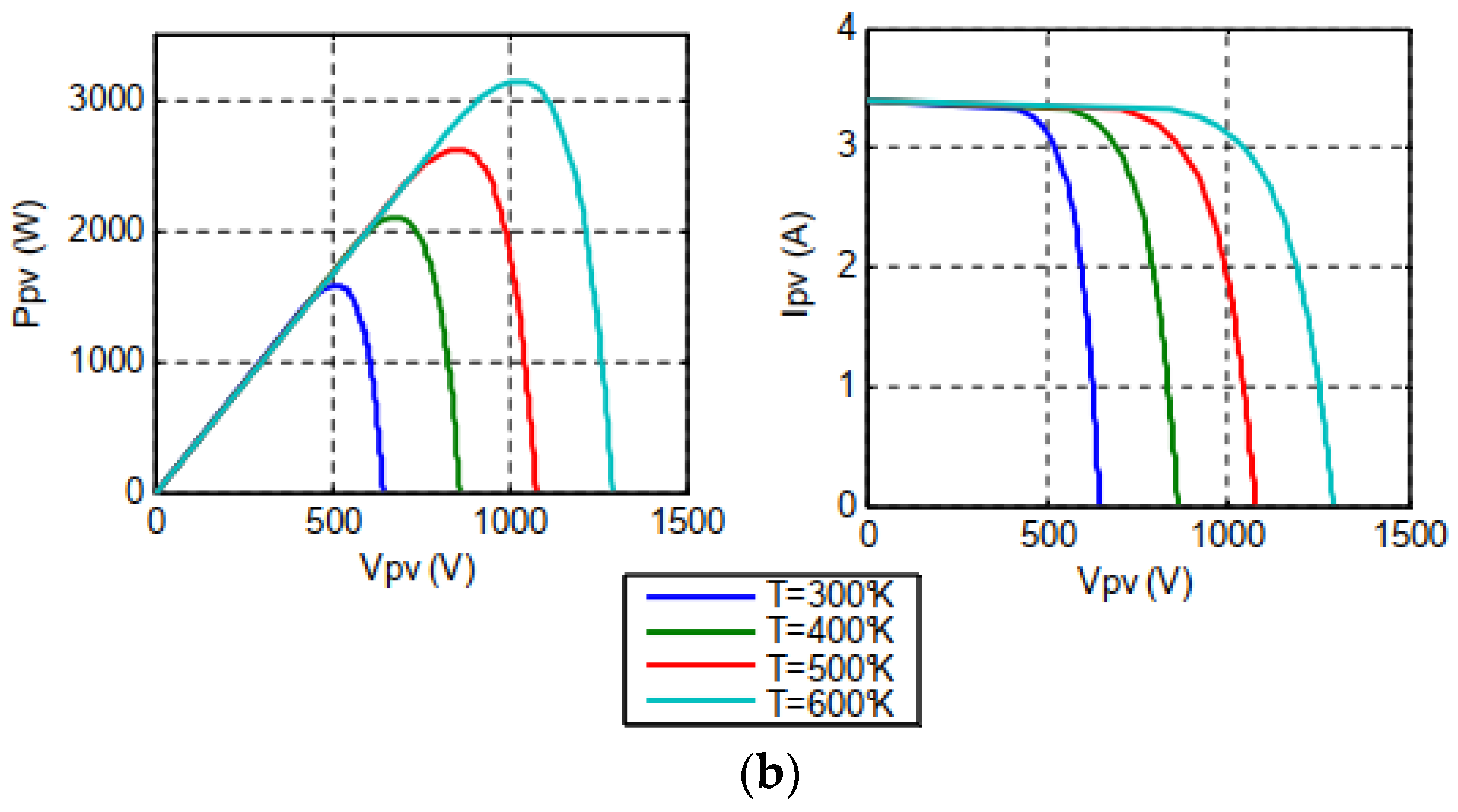

2.2.1. Modeling of the PV source

- -

- Ipv (A) and Vpv (V) are respectively the PV current and the PV voltage,

- -

- Iph (A) is the light generated current,

- -

- Rs (Ω) and Rsh (Ω) are respectively PV arrays series and shunt resistances,

- -

- A is the ideality factor of the PV panel, K is the Boltzmann constant, T (°K) is the temperature cell, q is the electronic charge and VT (V) is the thermodynamic potential of the PV cell.

2.2.2. Modeling of the DC-bus

2.2.3. Modeling of the three-phase inverter

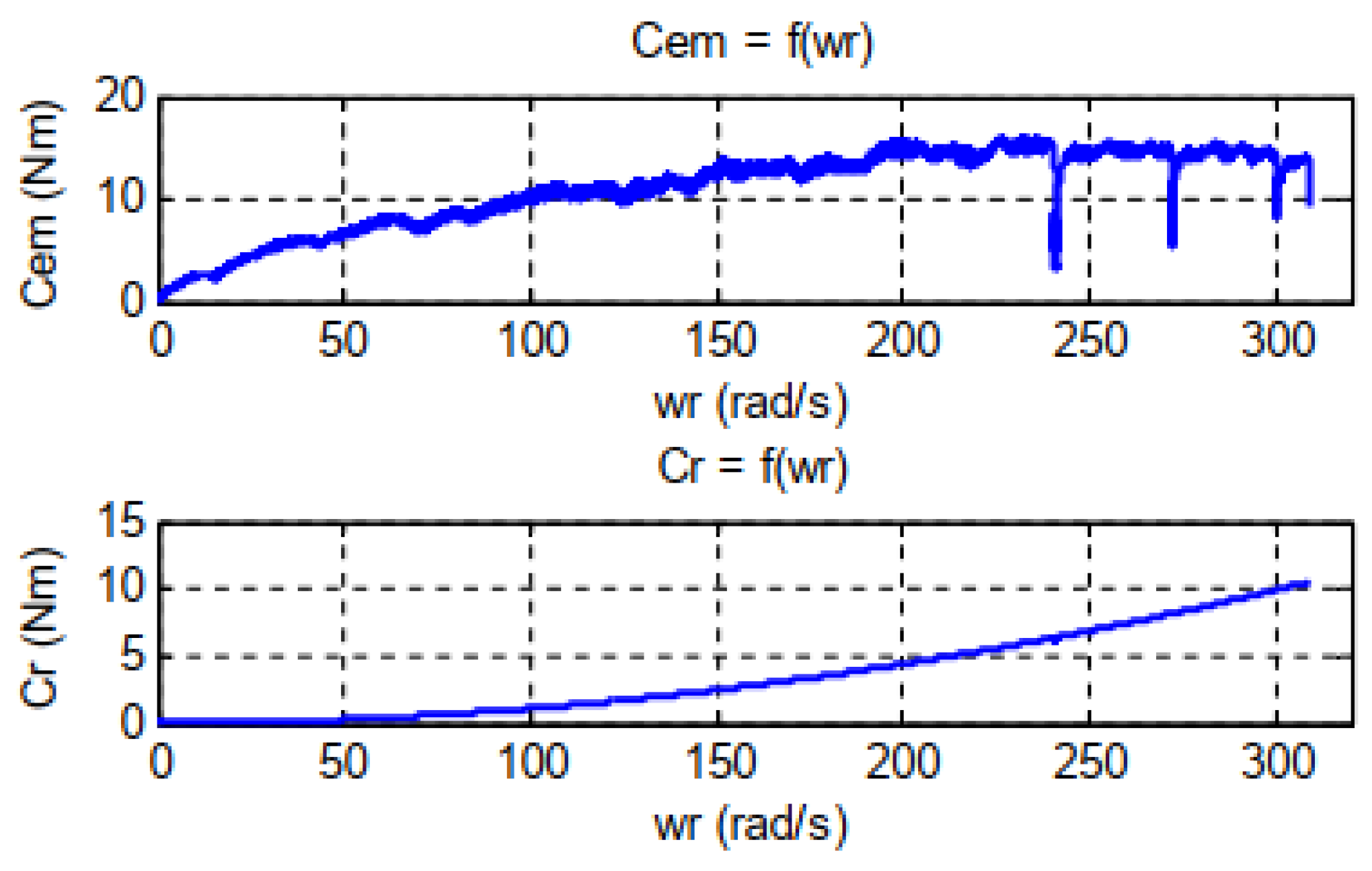

2.2.4. Modeling of the asynchronous motor pump

- -

- and are respectively the d and q stator currents,

- -

- and are respectively the d and q stator voltage,

- -

- and are respectively the d and q rotor flux,

- -

- and are respectively the stator and rotor electrical speed,

- -

- Rs and Rr are respectively the stator and rotor resistance,

- -

- and are respectively the stator and rotor inductance,

- -

- σ is a constant depending on motor parameters, M is the mutual inductance,

- -

- is the rotor inertia moment, is the number of poles pairs.

- -

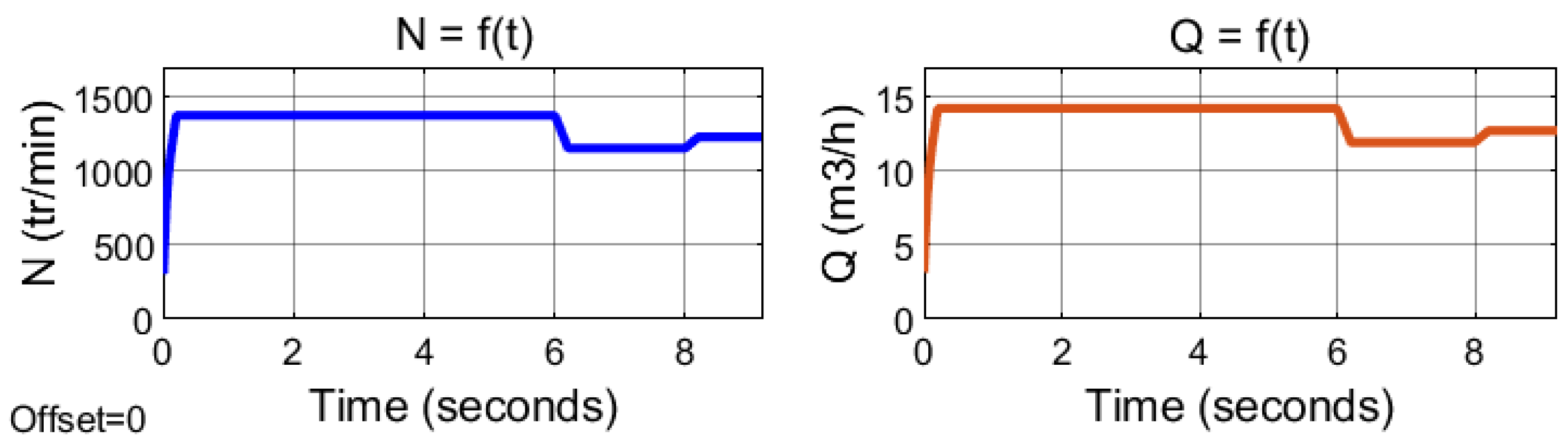

- N et N’ are the real and nominal pump speeds,

- -

- Q et Q’ are the real and nominal water flow,

- -

- H et H’ are the real and nominal pump heights.

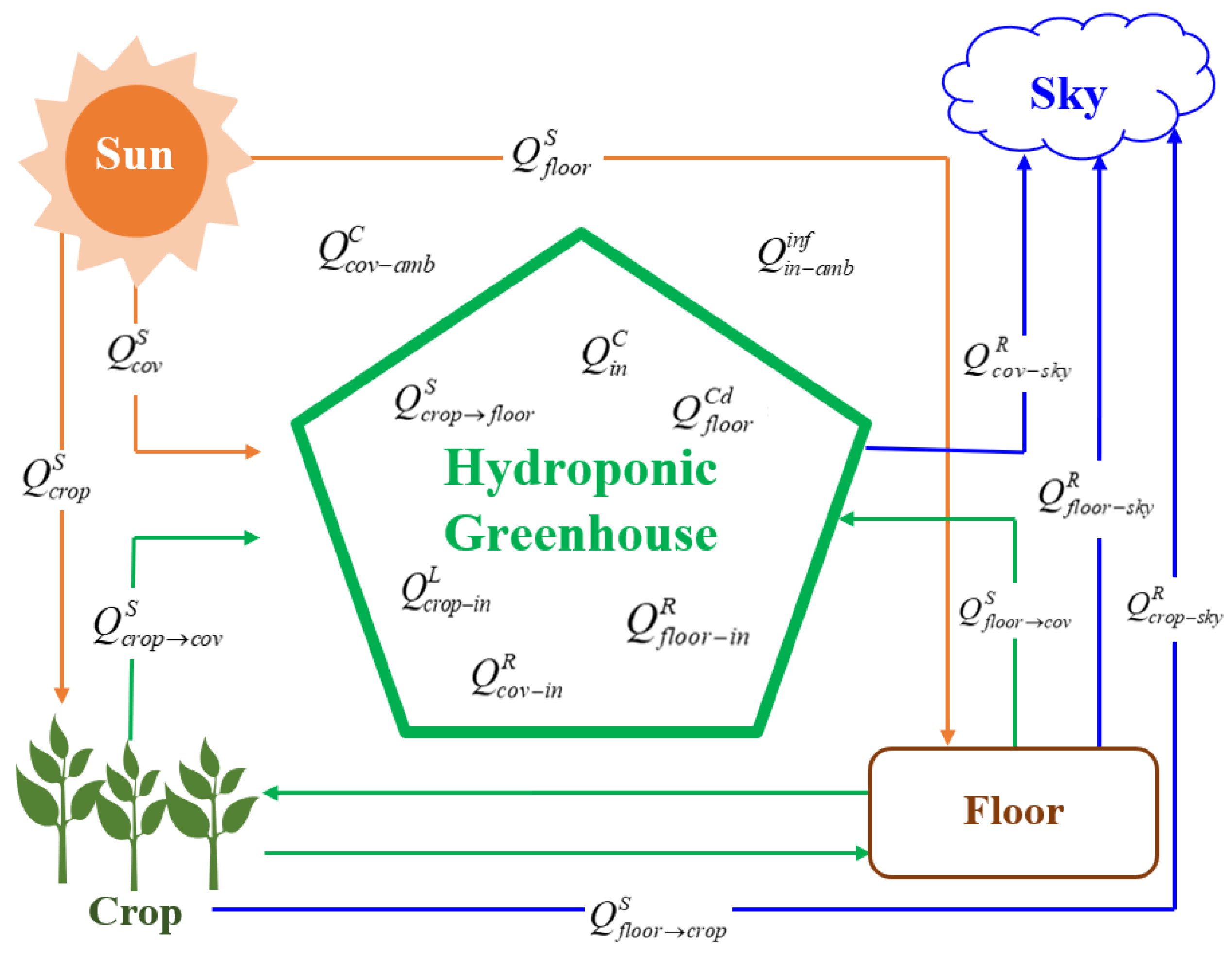

2.2.5. Modeling of the Hydroponic Greenhouse

- ▪

- are the absorbed heat of solar energy in all greenhouse components.

- ▪

- are the convective heat outside and inside the greenhouse.

- ▪

- is the heat exchanged by conduction from the floor.

- ▪

- is the heat losses by infiltration.

- ▪

- the heat exchanged by evapotranspiration of the crop.

- ▪

- are the heat losses due to radiation from the greenhouses and their surroundings.

- -

- : coverture temperature - : air density - : specific heat of air at constant pressure - : surface area of the coverture

- -

- : crop temperature - : surface area of the crop

- -

- : floor temperature - : surface area of the floor

- -

- : crop temperature - V: volume of the greenhouse.

2.3. Control of the PV-HG system

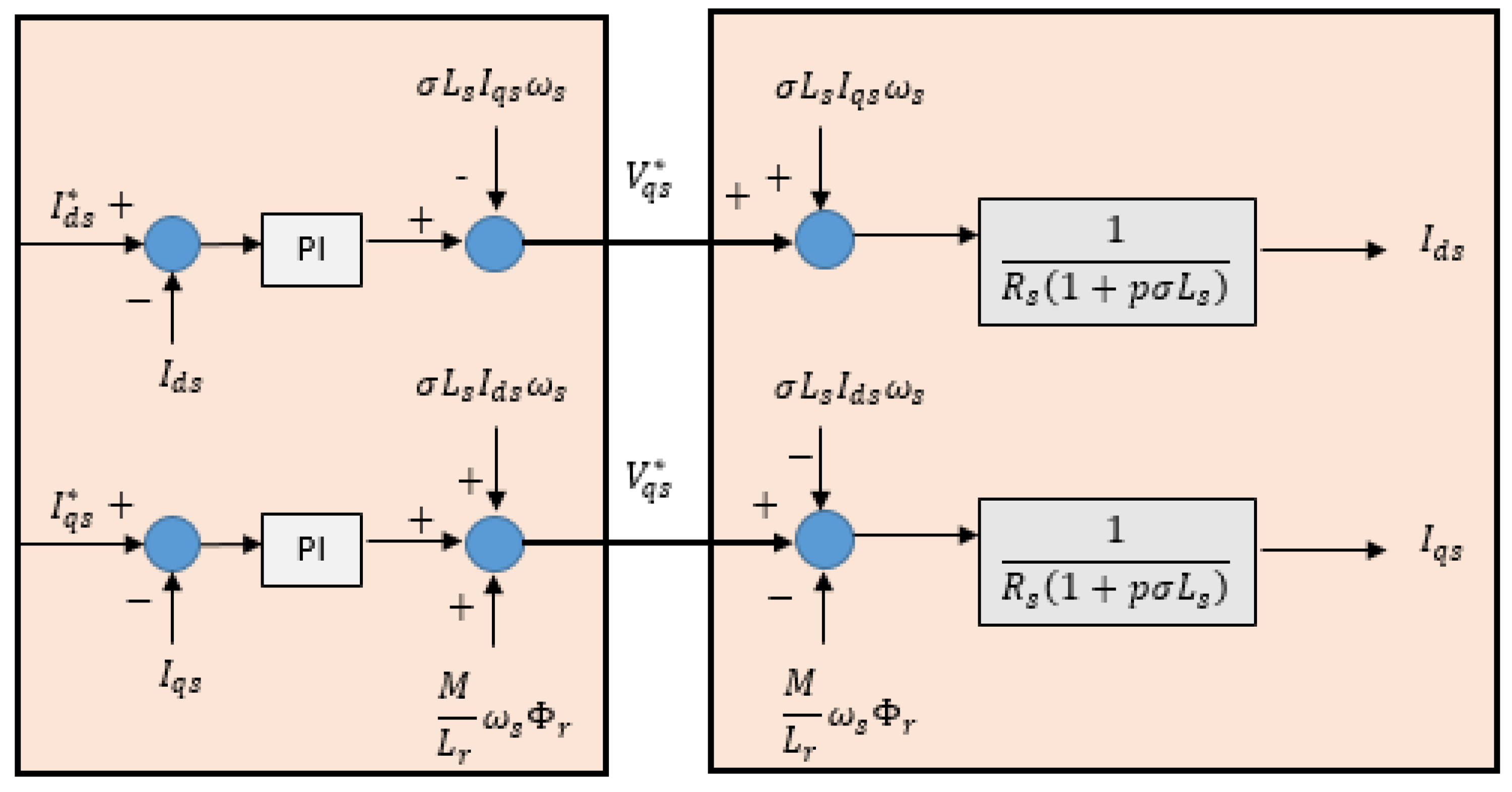

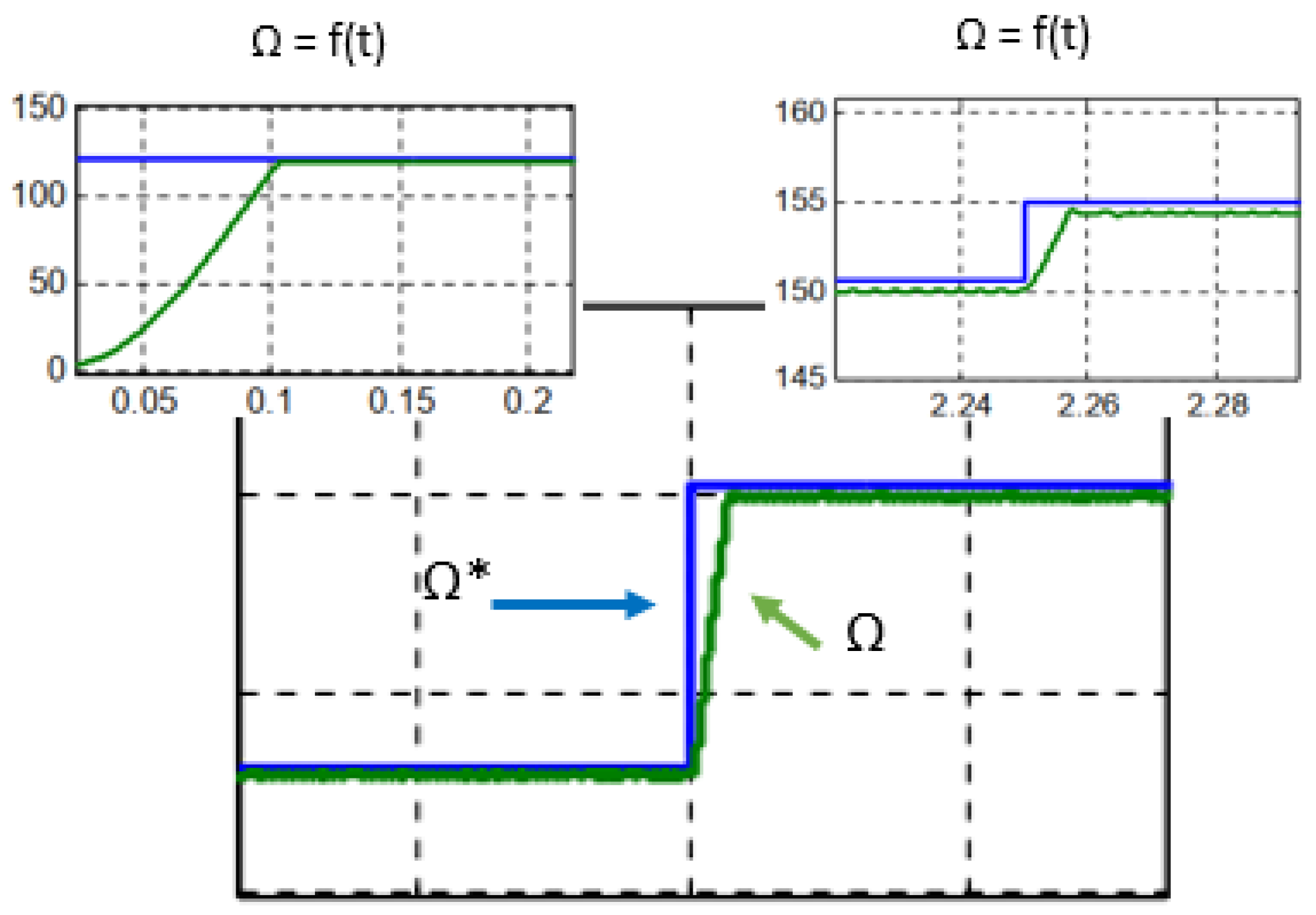

2.3.1. Field oriented control applied to the Asynchronous conditioning motor pump

- (a)

- Decoupling: It is interesting to add decoupling terms to make the d and q axes completely independent. Above all, this decoupling makes it possible to easily write the equations of the machine and the control part and thus calculate the coefficients of the speed and current controllers. By going through a Laplace transformation, the machine model can be placed under the following form described by Figure 7.

- (b)

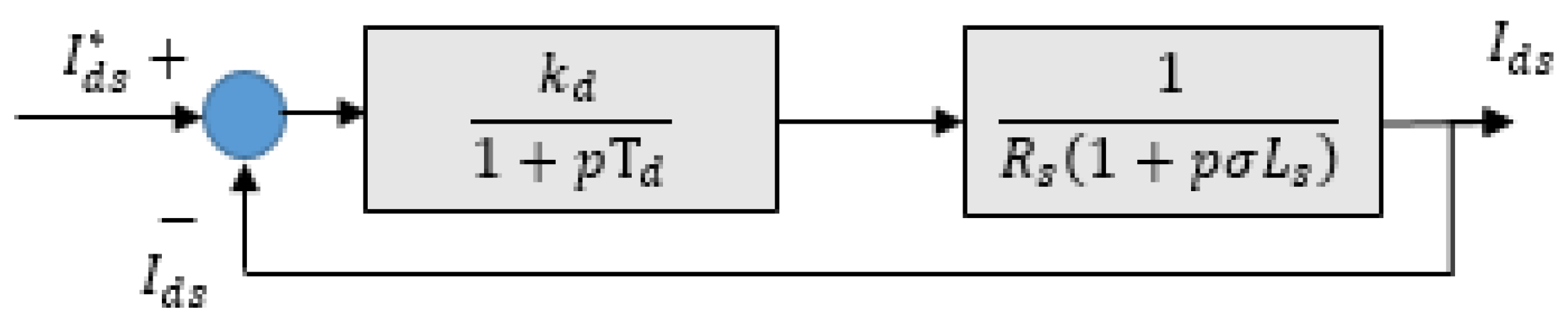

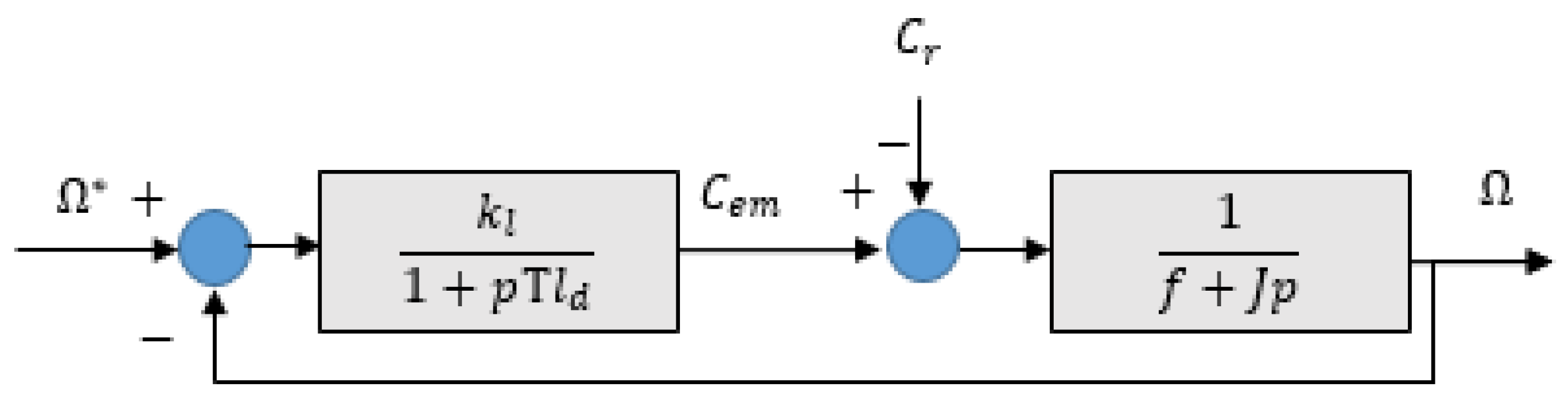

- Regulation loops: For controlling current and speed to their reference values, we implemented a conventional Proportional-Integral (PI) controller to adjust the control speed by proportional action and eliminate the static error between the controlled and actual variables by integral action. Figure 8 and 9 describe control loops for current and speed, respectively.

- (c)

- Reference values calculation: The reference values of rotor flux, and currents are respectively by (16) and (17).

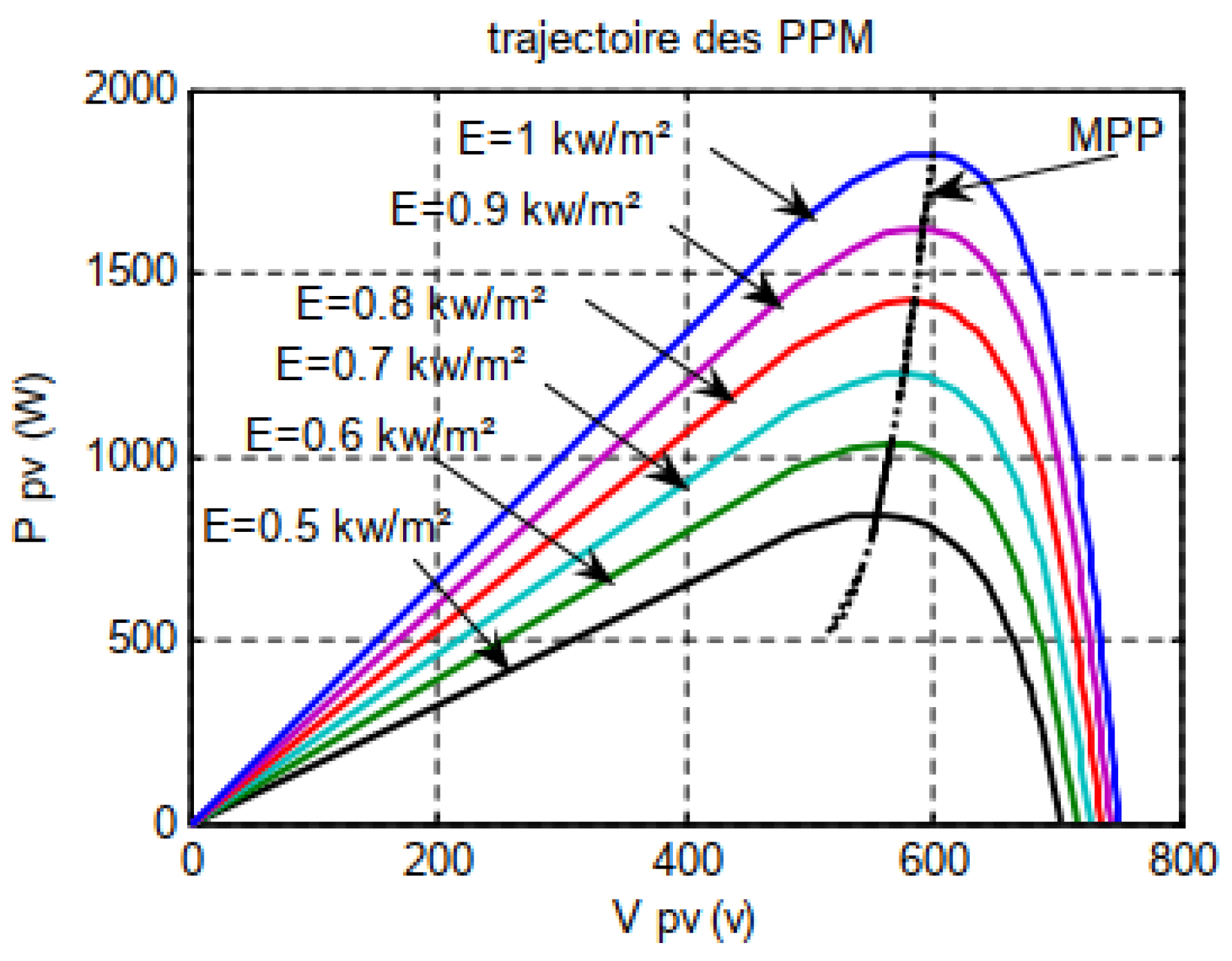

2.3.2. The MPPT polyfit-based control low

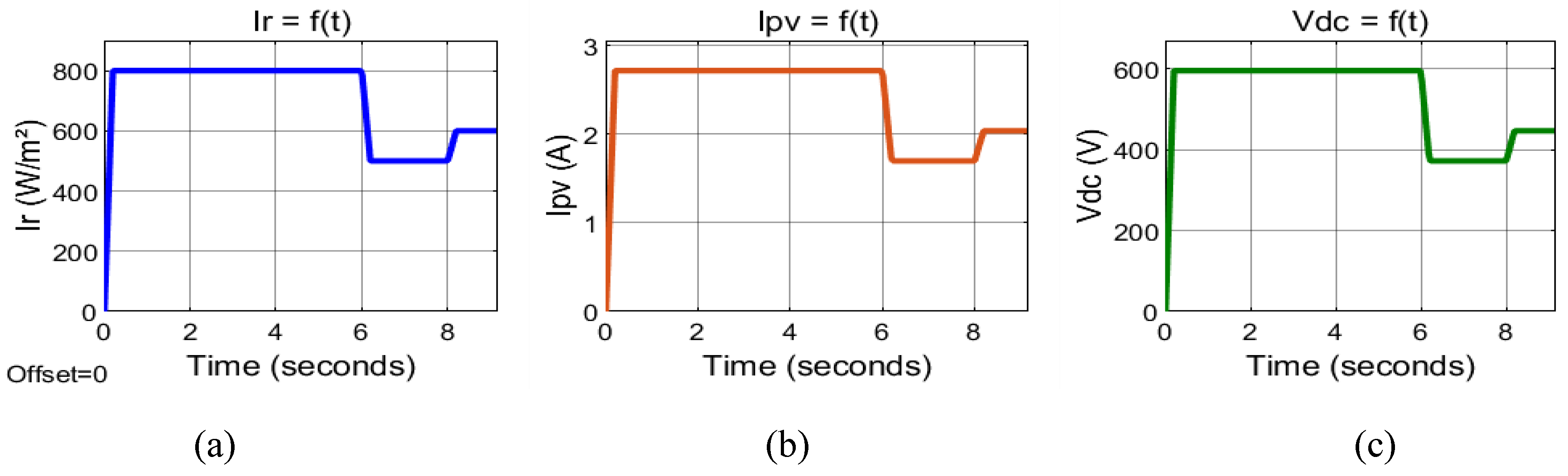

2.4. Simulation result of the PV-HG system with Matlab/Simulink

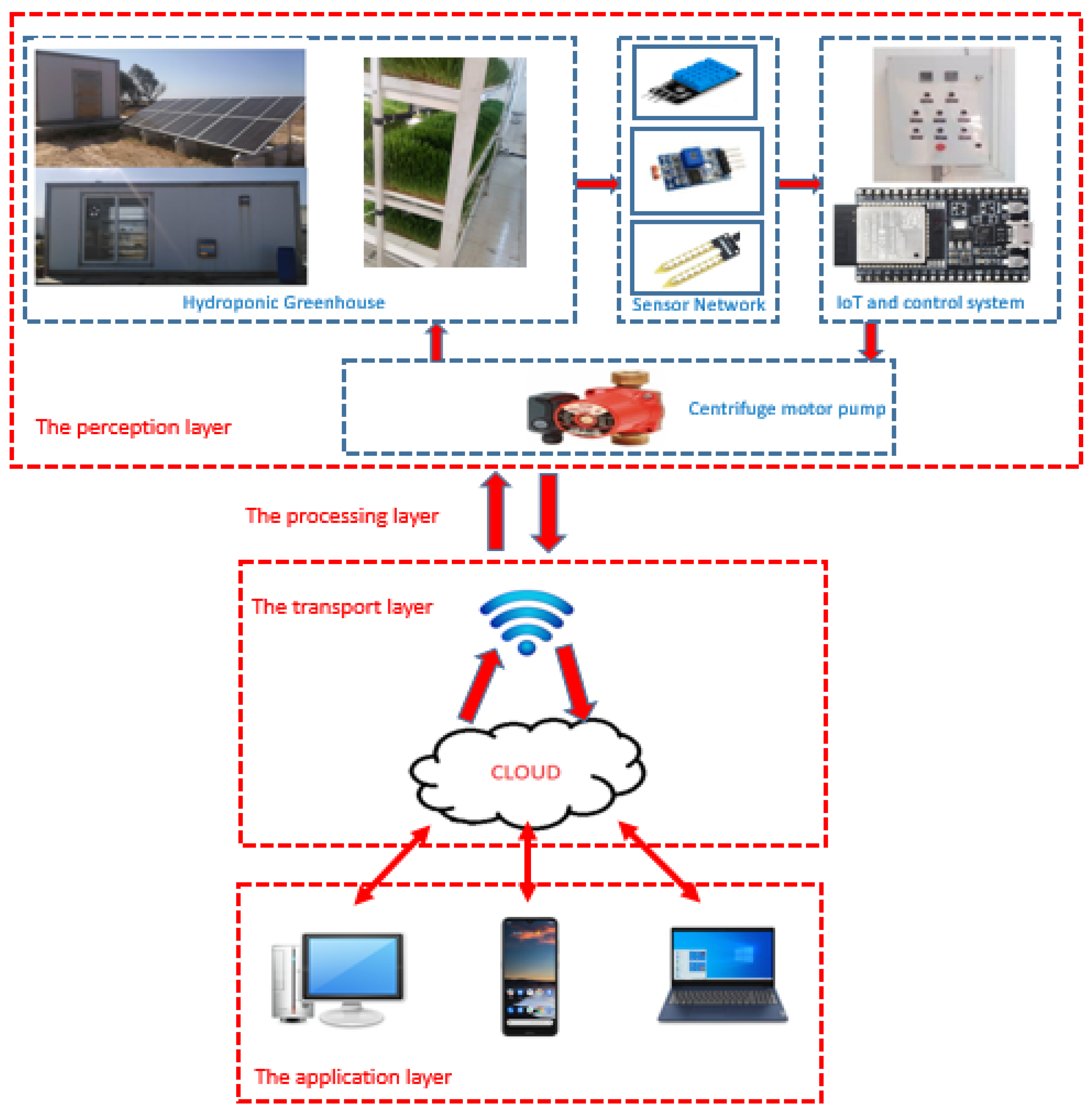

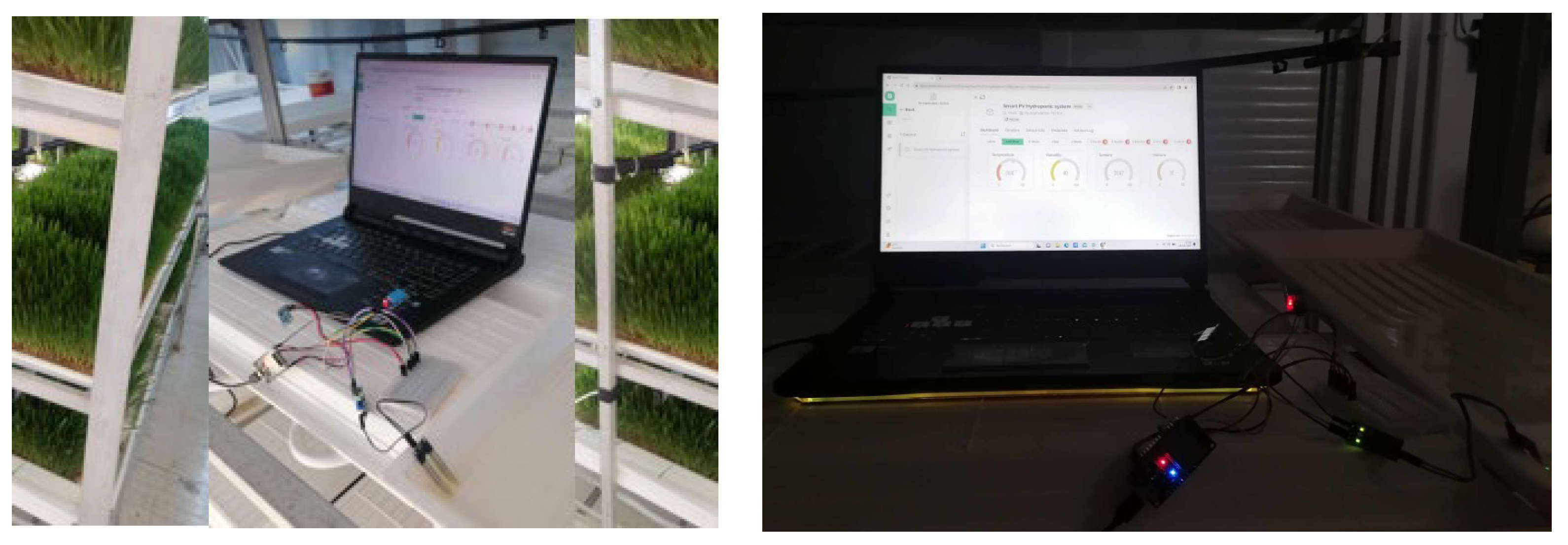

3. Experimental set-up

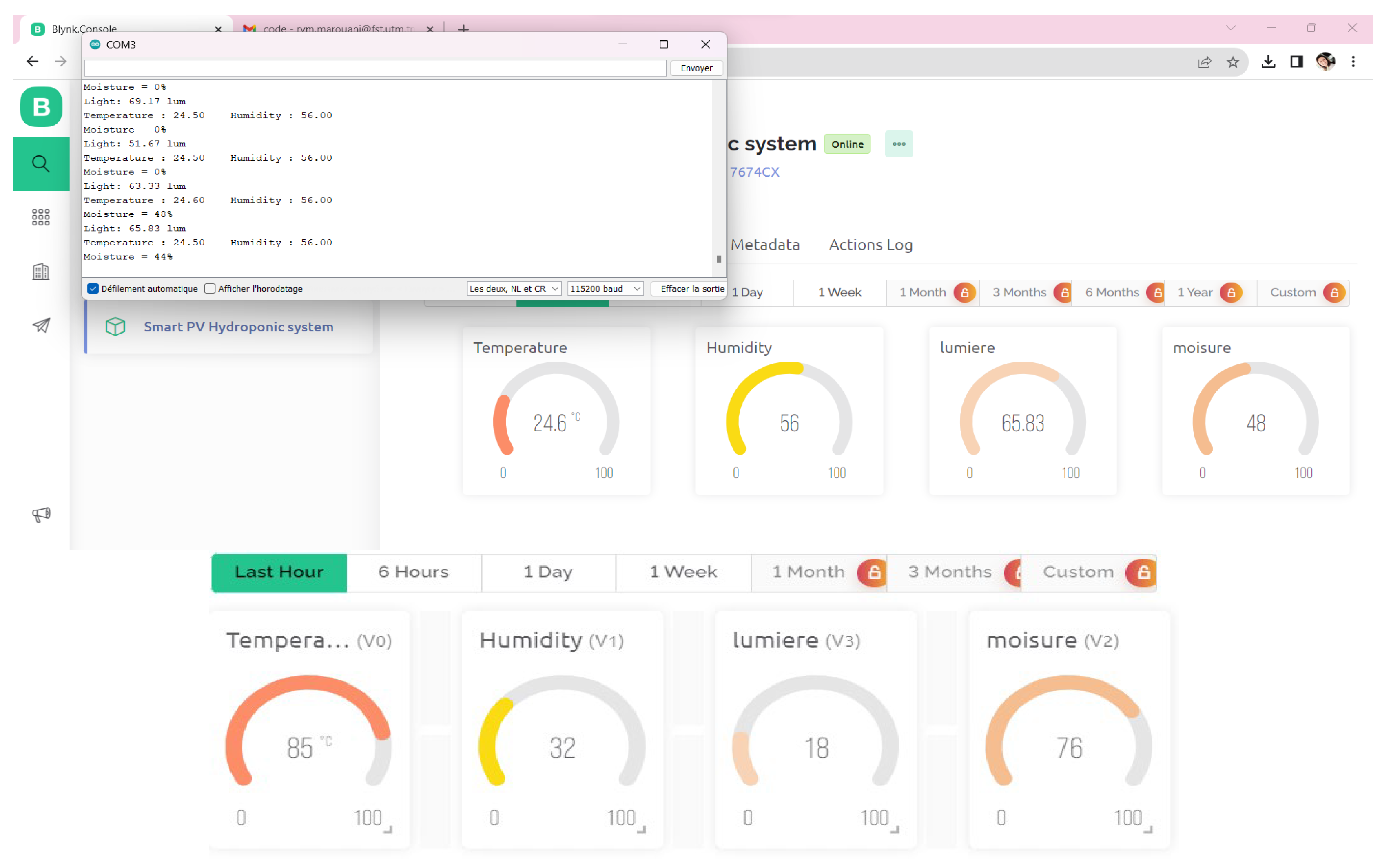

3.1. Implementation of Smart PV_HG control parameters

3.1.1. Temperature and humidity sensor

3.1.2. Soil moisture sensor

3.1.3. Light intensity sensor

3.1.4. ESP32 microcontroller

3.1.5. Development of a web application for remote controlling of the smart PV-HG system

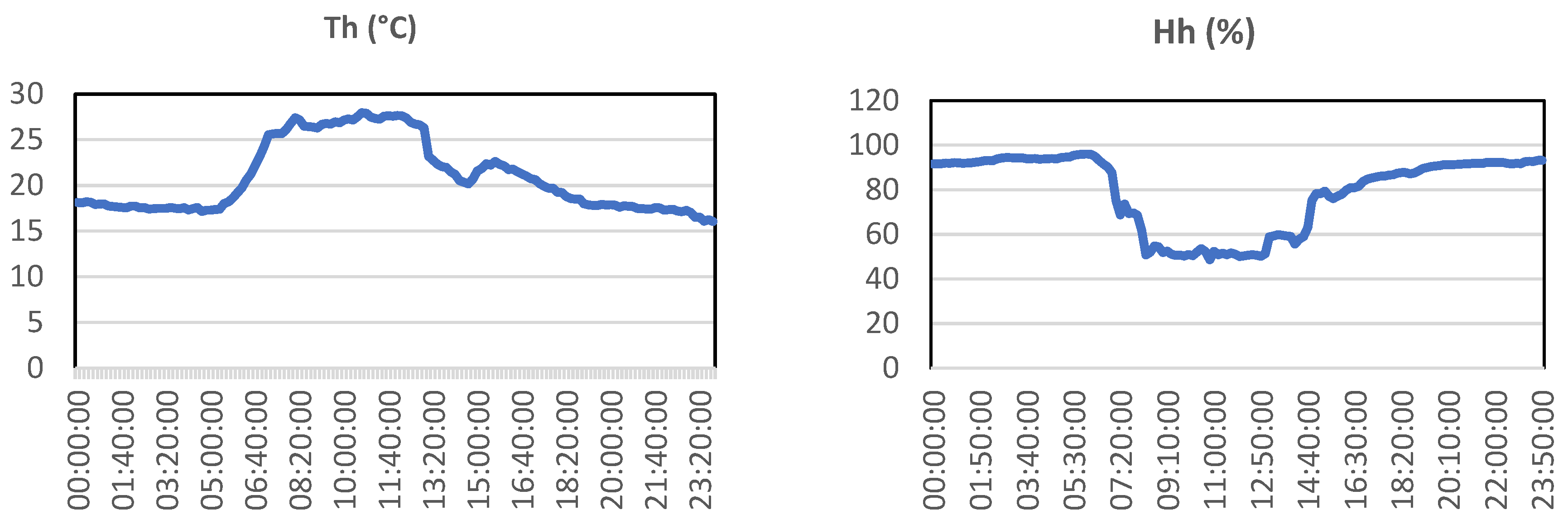

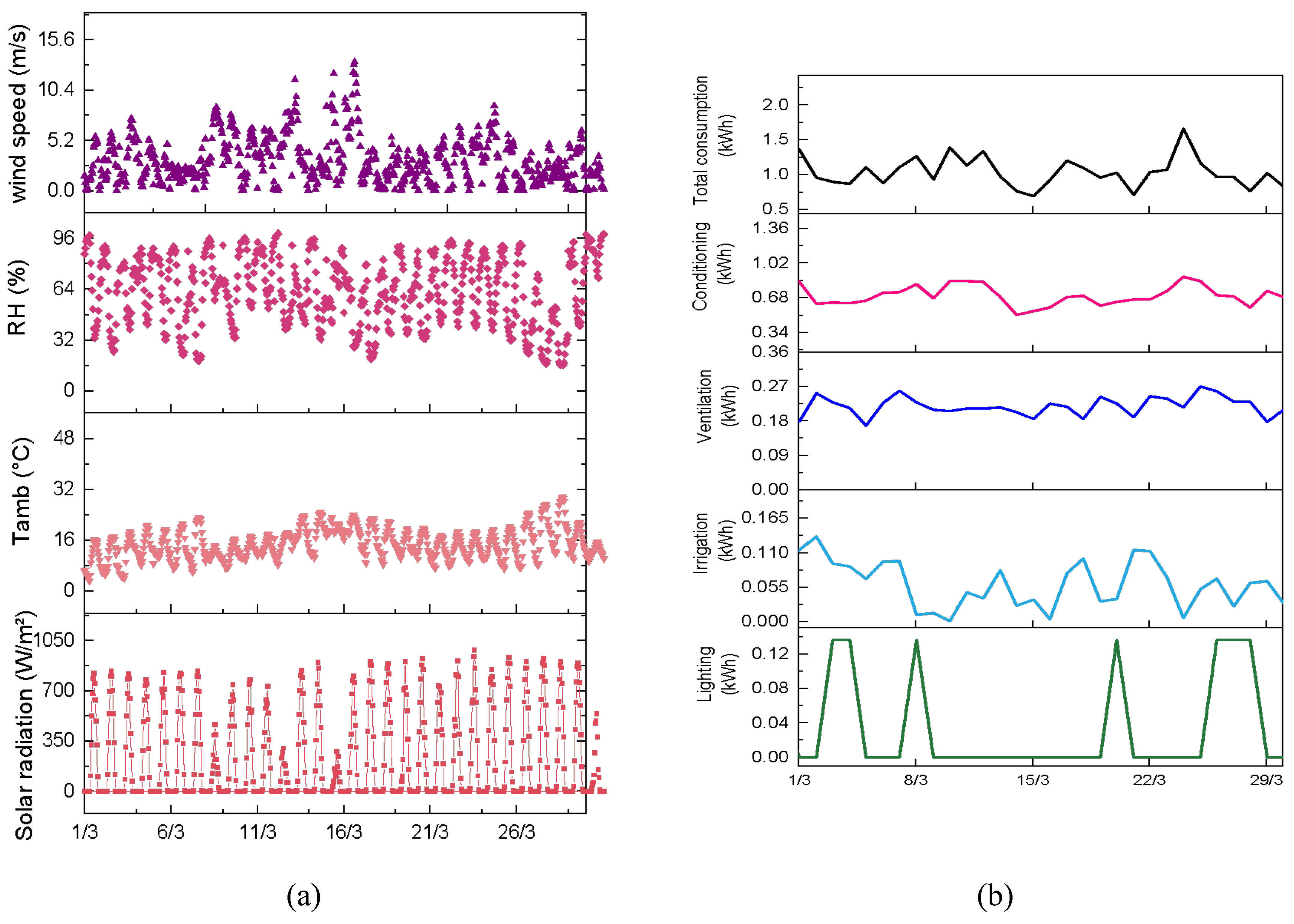

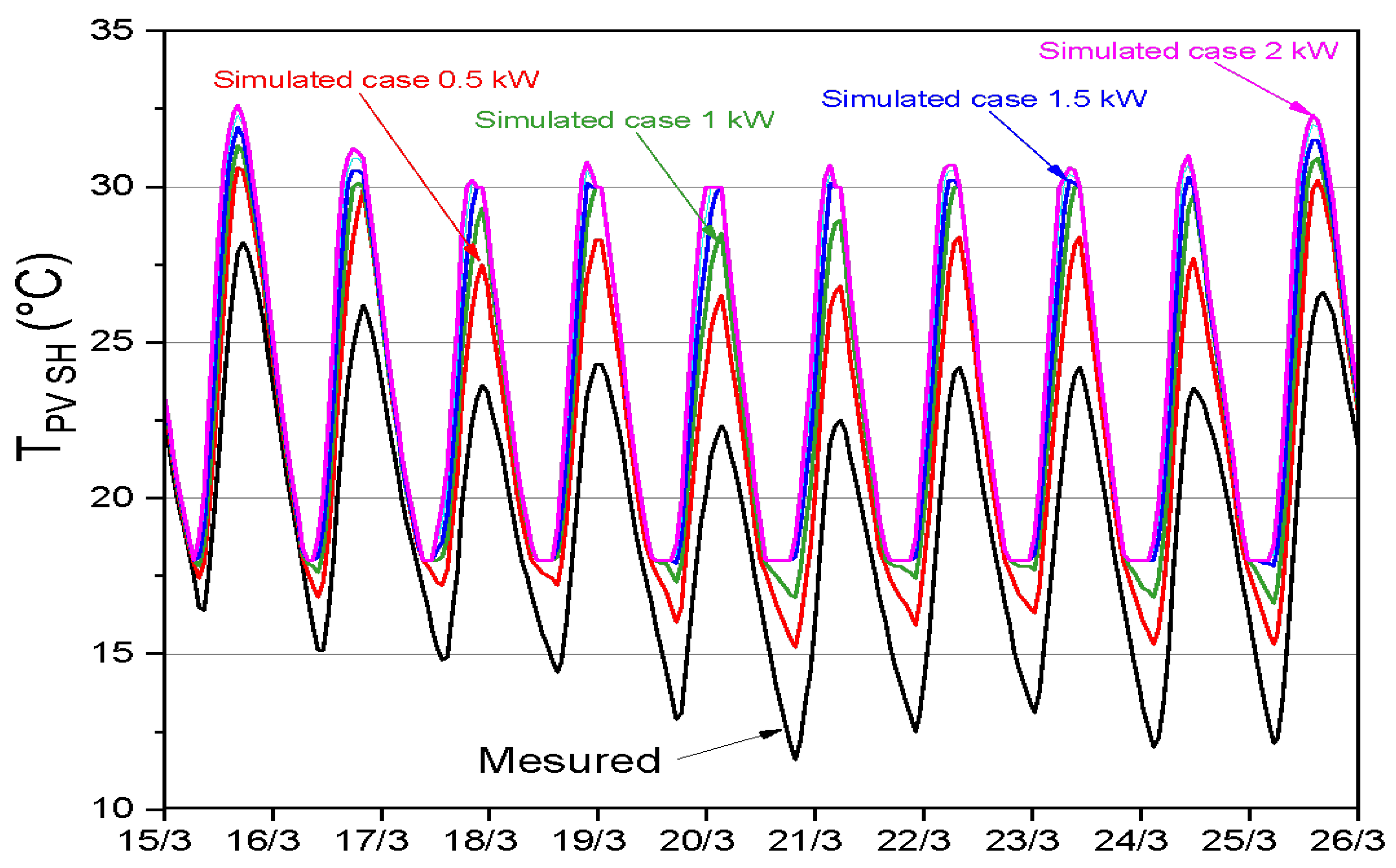

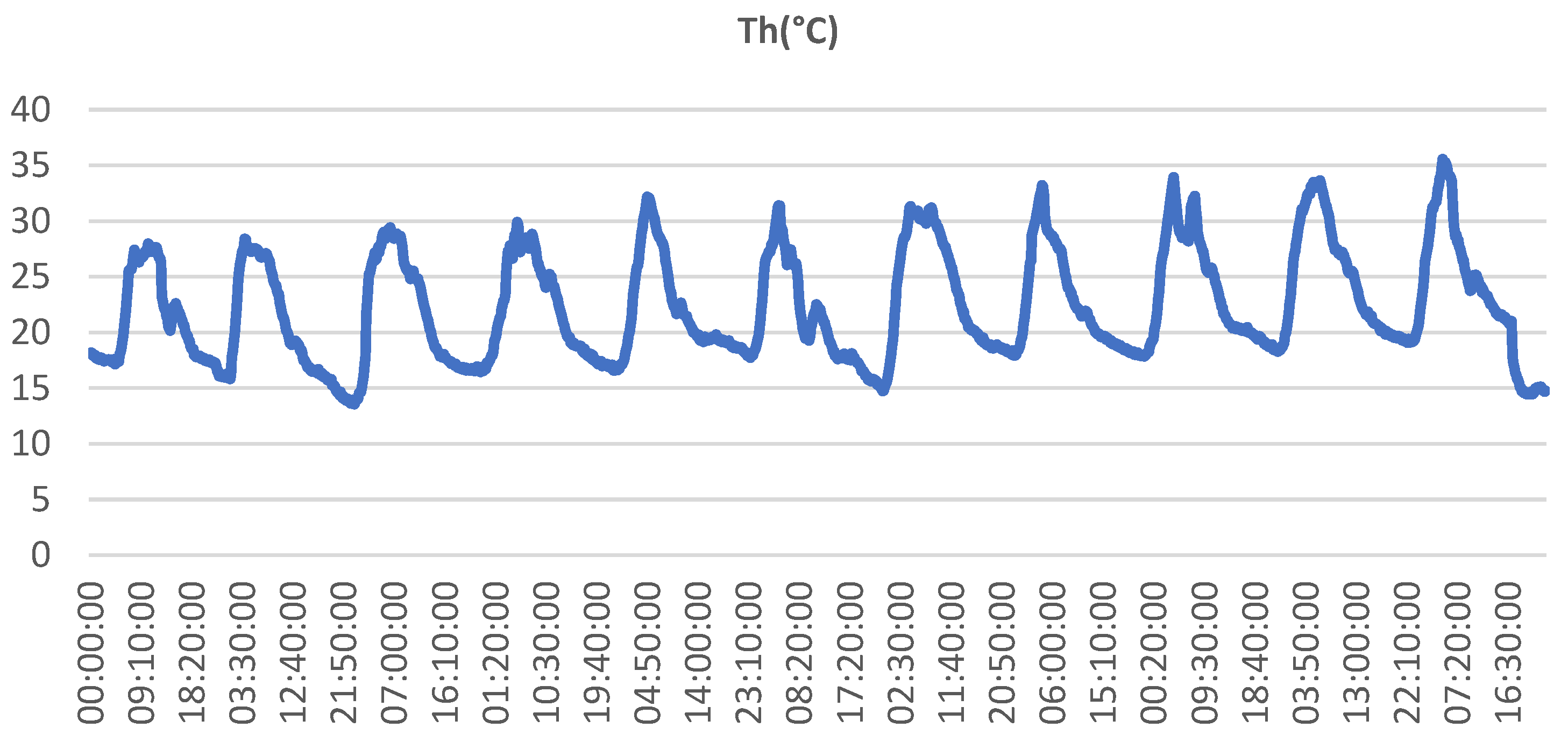

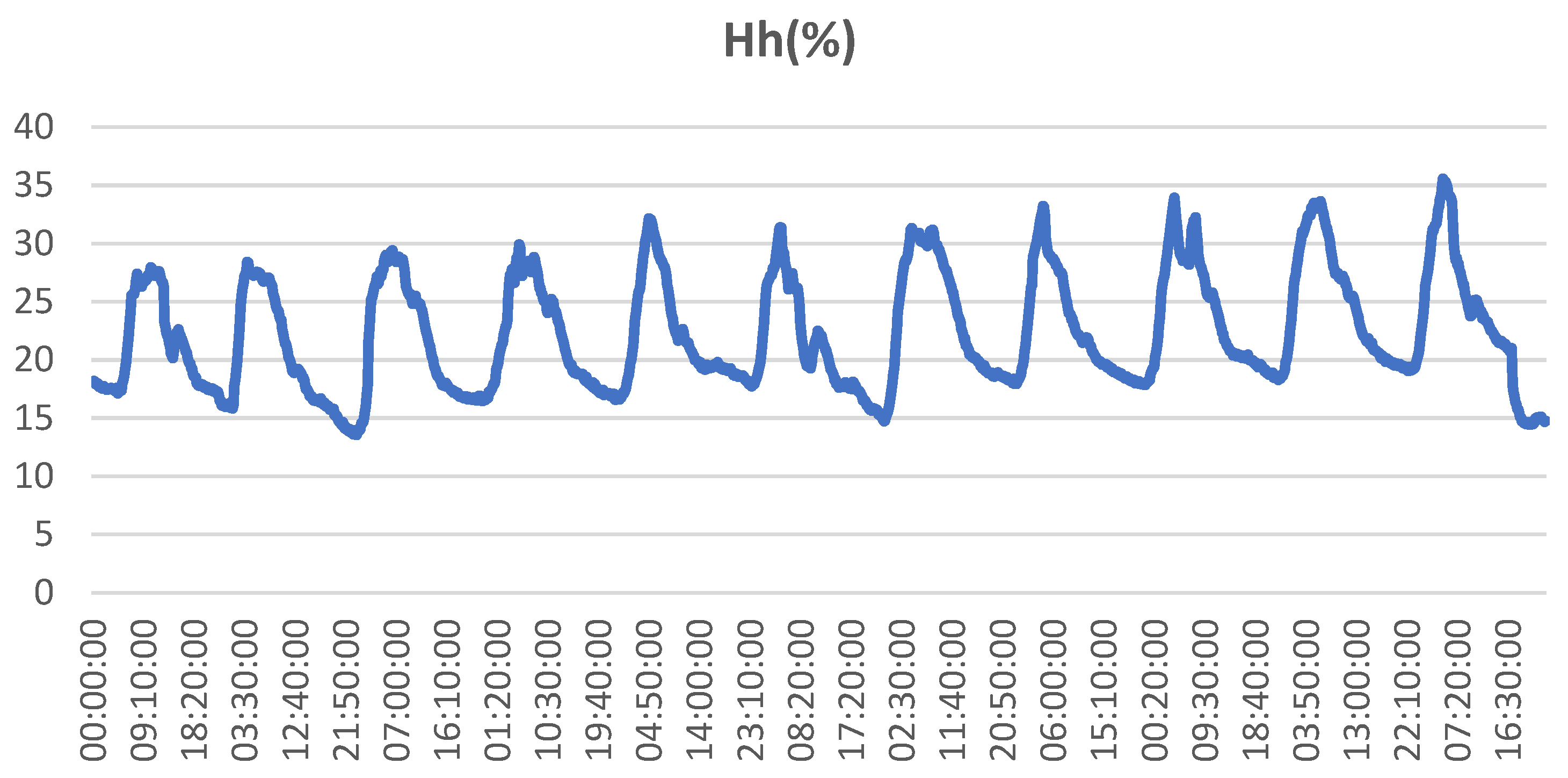

3.2. Experimental and numerical results and discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IRENA Renewable Energy in the Water, Energy and Food Nexus. International Renewable Energy Agency 2015, 1–125.

- Vadiee, A.; Martin, V. Energy Management Strategies for Commercial Greenhouses. Applied Energy 2014, 114, 880–888. [CrossRef]

- Qayyum, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, M.; Yu, Y.; Li, S.; Ahmad, W.; Maodaa, S.N.; Sayed, S.R.M.; Gan, J. Advancements in Technology and Innovation for Sustainable Agriculture: Understanding and Mitigating Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Agricultural Soils. Journal of Environmental Management 2023, 347, 119147. [CrossRef]

- Sarfraz, M.; Iqbal, K.; Wang, Y.; Bhutta, M.S.; Jaffri, Z. ul A. Role of Agricultural Resource Sector in Environmental Emissions and Its Explicit Relationship with Sustainable Development: Evidence from Agri-Food System in China. Resources Policy 2023, 80, 103191. [CrossRef]

- Shanmugavel, D.; Rusyn, I.; Solorza-Feria, O.; Kamaraj, S.K. Sustainable SMART Fertilizers in Agriculture Systems: A Review on Fundamentals to in-Field Applications. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 904, 166729. [CrossRef]

- Taoumi, H.; Lahrech, K. Economic, Environmental and Social Efficiency and Effectiveness Development in the Sustainable Crop Agricultural Sector: A Systematic in-Depth Analysis Review. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 901, 165761. [CrossRef]

- Bernzen, A.; Sohns, F.; Jia, Y.; Braun, B. Crop Diversification as a Household Livelihood Strategy under Environmental Stress. Factors Contributing to the Adoption of Crop Diversification in Shrimp Cultivation and Agricultural Crop Farming Zones of Coastal Bangladesh. Land Use Policy 2023, 132, 106796. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, Z.; Zhu, Q.; Wang, C.; Tang, X. Review on Arsenic Environment Behaviors in Aqueous Solution and Soil. Chemosphere 2023, 333, 138869. [CrossRef]

- Rehman, H. ur; Hirvonen, J.; Sirén, K. Influence of Technical Failures on the Performance of an Optimized Community-Size Solar Heating System in Nordic Conditions. Journal of Cleaner Production 2018, 175, 624–640. [CrossRef]

- Dantas, J.L.D.; Theotokatos, G. A Framework for the Economic-Environmental Feasibility Assessment of Short-Sea Shipping Autonomous Vessels. Ocean Engineering 2023, 279, 114420. [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Wahab, S.A.; Charabi, Y.; Al-Mahruqi, A.M.; Osman, I. Design and Evaluation of a Hybrid Energy System for Masirah Island in Oman. International Journal of Sustainable Engineering 2020, 00, 288–297. [CrossRef]

- Salata, F.; Golasi, I.; Domestico, U.; Banditelli, M.; Lo Basso, G.; Nastasi, B.; de Lieto Vollaro, A. Heading towards the NZEB through CHP+HP Systems. A Comparison between Retrofit Solutions Able to Increase the Energy Performance for the Heating and Domestic Hot Water Production in Residential Buildings. Energy Conversion and Management 2017, 138, 61–76. [CrossRef]

- Omar, M.N.; Taha, A.T.; Samak, A.A.; Keshek, M.H.; Gomaa, E.M.; Elsisi, S.F. Simulation and Validation Model of Cooling Greenhouse by Solar Energy (P V) Integrated with Painting Its Cover and Its Effect on the Cucumber Production. Renewable Energy 2021, 172, 1154–1173. [CrossRef]

- Ghosal, M.K.; Tiwari, G.N. Mathematical Modeling for Greenhouse Heating by Using Thermal Curtain and Geothermal Energy. Solar Energy 2004, 76, 603–613. [CrossRef]

- Boughanmi, H.; Lazaar, M.; Bouadila, S.; Farhat, A. Thermal Performance of a Conic Basket Heat Exchanger Coupled to a Geothermal Heat Pump for Greenhouse Cooling under Tunisian Climate. Energy & Buildings 2015, 104, 87–96. [CrossRef]

- Boughanmi, H.; Lazaar, M.; Bouadila, S.; Farhat, A. Thermal Performance of a Conic Basket Heat Exchanger Coupled to a Geothermal Heat Pump for Greenhouse Cooling under Tunisian Climate. Energy and Buildings 2015, 104. [CrossRef]

- Chau, J.; Sowlati, T.; Sokhansanj, S.; Preto, F.; Melin, S.; Bi, X. Techno-Economic Analysis of Wood Biomass Boilers for the Greenhouse Industry. Applied Energy 2009, 86, 364–371. [CrossRef]

- Bibbiani, C.; Campiotti, C.A.; Schettini, E.; Vox, G. A Sustainable Energy for Greenhouses Heating in Italy: Wood Biomass. Acta Horticulturae 2017, 1170, 523–530. [CrossRef]

- Tractebel GUIDE DÉTAILLÉ “PROJETS D’ÉNERGIE RENOUVELABLE EN TUNISIE”; 2019;

- Msigwa, G.; Ighalo, J.O.; Yap, P.S. Considerations on Environmental, Economic, and Energy Impacts of Wind Energy Generation: Projections towards Sustainability Initiatives. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 849, 157755. [CrossRef]

- Uchman, W.; Kotowicz, J.; Sekret, R. Investigation on Green Hydrogen Generation Devices Dedicated for Integrated Renewable Energy Farm: Solar and Wind. Applied Energy 2022, 328, 120170. [CrossRef]

- Cossu, M.; Cossu, A.; Deligios, P.A.; Ledda, L.; Li, Z.; Fatnassi, H.; Poncet, C.; Yano, A. Assessment and Comparison of the Solar Radiation Distribution inside the Main Commercial Photovoltaic Greenhouse Types in Europe. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2018, 94, 822–834. [CrossRef]

- Ezzaeri, K.; Fatnassi, H.; Bouharroud, R.; Gourdo, L.; Bazgaou, A.; Wifaya, A.; Demrati, H.; Bekkaoui, A.; Aharoune, A.; Poncet, C.; et al. The e Ff Ect of Photovoltaic Panels on the Microclimate and on the Tomato Production under Photovoltaic Canarian Greenhouses. Solar Energy 2018, 173, 1126–1134. [CrossRef]

- Alinejad, T.; Yaghoubi, M.; Vadiee, A. Thermo-Environomic Assessment of an Integrated Greenhouse with an Adjustable Solar Photovoltaic Blind System. Renewable Energy 2020, 156, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Global Energy Review 2020. Global Energy Review 2019 2020. [CrossRef]

- Faraji, J.; Hashemi-Dezaki, H.; Ketabi, A. Multi-Year Load Growth-Based Optimal Planning of Grid-Connected Microgrid Considering Long-Term Load Demand Forecasting: A Case Study of Tehran, Iran. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments 2020, 42, 1–51. [CrossRef]

- Duarte, R.; García-Riazuelo, Á.; Sáez, L.A.; Sarasa, C. Analysing Citizens’ Perceptions of Renewable Energies in Rural Areas: A Case Study on Wind Farms in Spain. Energy Reports 2022, 8, 12822–12831. [CrossRef]

- Minoofar, A.; Gholami, A.; Eslami, S.; Hajizadeh, A.; Gholami, A.; Zandi, M.; Ameri, M.; Kazem, H.A. Renewable Energy System Opportunities: A Sustainable Solution toward Cleaner Production and Reducing Carbon Footprint of Large-Scale Dairy Farms. Energy Conversion and Management 2023, 293, 117554. [CrossRef]

- Alturki, F.A.; Al-Shamma’a, A.A.; Farh, H.M.H.; AlSharabi, K. Optimal Sizing of Autonomous Hybrid Energy System Using Supply-Demand-Based Optimization Algorithm. International Journal of Energy Research 2021, 45, 605–625. [CrossRef]

- Cherif, D.; Bouadila, S. Enhancing Crop Yield in Hydroponic Greenhouses : Integrating Latent Heat Storage and Forced Ventilation Systems for Improved Thermal Stratification (Under Review). Thermal Science and Engineering Progress 2023, TSEP-D-23-, 102163. [CrossRef]

- Boccalatte, A.; Fossa, M.; Sacile, R. Modeling, Design and Construction of a Zero-Energy PV Greenhouse for Applications in Mediterranean Climates. Thermal Science and Engineering Progress 2021, 25, 101046.

- Aziz, A.S.; Tajuddin, M.F.N.; Zidane, T.E.K.; Su, C.L.; Alrubaie, A.J.K.; Alwazzan, M.J. Techno-Economic and Environmental Evaluation of PV/Diesel/Battery Hybrid Energy System Using Improved Dispatch Strategy. Energy Reports 2022, 8, 6794–6814. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, X.; Han, X.; Wei, S.; Novakovic, V. Comparative Study on Shading Performance of MHP-PV/T inside and Outside Chinese Greenhouse in Winter. Solar energy 2022, 240, 269–279.

- Yildiz, A.; Ozgener, O.; Ozgener, L. Exergetic Performance Assessment of Solar Photovoltaic Cell (PV) Assisted Earth to Air Heat Exchanger (EAHE) System for Solar Greenhouse Cooling. Energy and Buildings 2011, 43, 3154–3160. [CrossRef]

- Baddadi, S.; Bouadila, S.; Ghorbel, W.; Guizani, A. Autonomous Greenhouse Microclimate through Hydroponic Design and Refurbished Thermal Energy by Phase Change Material . Journal of Cleaner Production 2018, 11, 192. [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, G.L.; Almeida Gadelha, F.D.; Kublik, N.; Proctor, A.; Reichelm, L.; Weissinger, E.; Wohlleb, G.M.; Halden, R.U. Comparison of Land, Water, and Energy Requirements of Lettuce Grown Using Hydroponic vs. Conventional Agricultural Methods. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2015, 12, 6879–6891. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Elomri, A.; Al-Ansari, T.; Kerbache, L.; El Mekkawy, T. Decisions on Design and Planning of Solar-Assisted Hydroponic Farms under Various Subsidy Schemes. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2022, 156, 111958. [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.S.; Javid, R.; Riaz, S.; Atal, Z. IoT Based Smart Greenhouse Framework and Control Strategies for Sustainable Agriculture. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 99394–99420. [CrossRef]

- Sadek, N.; kamal, N.; Shehata, D. Internet of Things Based Smart Automated Indoor Hydroponics and Aeroponics Greenhouse in Egypt. Ain Shams Engineering Journal 2023, 102341. [CrossRef]

- Sudana, D.; Eman, D.; Suyoto Iot Based: Hydroponic Using Drip Non-Circulation System for Paprika. Proceeding - 2019 International Conference of Artificial Intelligence and Information Technology, ICAIIT 2019 2019, 124–128. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, M.B.; Costa, B.A.; Lemos, J.M. Hydroponic Greenhouse Crop Optimization. 13th APCA International Conference on Control and Soft Computing, CONTROLO 2018 - Proceedings 2018, 270–275. [CrossRef]

- Chaiwongsai, J. Automatic Control and Management System for Tropical Hydroponic Cultivation. Proceedings - IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems 2019, 2019-May, 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Al-Naemi, S.; Al-Otoom, A. Smart Sustainable Greenhouses Utilizing Microcontroller and IOT in the GCC Countries; Energy Requirements & Economical Analyses Study for a Concept Model in the State of Qatar. Results in Engineering 2023, 17, 100889. [CrossRef]

- Andrianto, H.; Suhardi; Faizal, A. Development of Smart Greenhouse System for Hydroponic Agriculture. 2020 International Conference on Information Technology Systems and Innovation, ICITSI 2020 - Proceedings 2020, 335–340. [CrossRef]

- Bouadila, S.; Baddadi, S.; Skouri, S.; Ayed, R. Assessing Heating and Cooling Needs of Hydroponic Sheltered System in Mediterranean Climate: A Case Study Sustainable Fodder Production. Energy 2022, 261, 125274. [CrossRef]

- Bouadila, S.; Baddadi, S.; Ben Ali, R.; Ayed, R.; Skouri, S. Deploying Low-Carbon Energy Technologies in Soilless Vertical Agricultural Greenhouses in Tunisia. Thermal Science and Engineering Progress 2023, 42, 101896. [CrossRef]

- Mahjoub, S.; Chrifi-Alaoui, L.; Drid, S.; Derbel, N. Control and Implementation of an Energy Management Strategy for a PV–Wind–Battery Microgrid Based on an Intelligent Prediction Algorithm of Energy Production. Energies 2023, 16, 1883. [CrossRef]

- Zaouche, F.; Rekioua, D.; Gaubert, J.P.; Mokrani, Z. Supervision and Control Strategy for Photovoltaic Generators with Battery Storage. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 19536–19555. [CrossRef]

- Samrat, N.H.; Ahmad, N. Bin; Choudhury, I.A.; Taha, Z. Bin Modeling, Control, and Simulation of Battery Storage Photovoltaic-Wave Energy Hybrid Renewable Power Generation Systems for Island Electrification in Malaysia. Scientific World Journal 2014, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Aguilar, R.S.; Dòria-Cerezo, A.; Puleston, P.F. Direct Synchronous-Asynchronous Conversion System for Hybrid Electrical Vehicle Applications. An Energy-Based Modeling Approach. International Journal of Electrical Power and Energy Systems 2013, 47, 264–279. [CrossRef]

- Ben Ali, R.; Bouadila, S.; Mami, A. Development of a Fuzzy Logic Controller Applied to an Agricultural Greenhouse Experimentally Validated. Applied Thermal Engineering 2018, 141, 798–810. [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhang, Z.; Mei, X.; Rodríguez, J.; Kennel, R. Advanced Control Strategies of Induction Machine: Field Oriented Control, Direct Torque Control and Model Predictive Control. Energies 2018, 11. [CrossRef]

- Marouani, R.; Sellami, M.A.; Mami, A. Cascade sliding mode control applied to a photovoltaic water pumping system with maximum power point tracker. 2014 International Conference on Advanced Technologies for Signal and Image Processing (ATSIP) March 2014. [CrossRef]

- Marouani, R.; Bacha, F, Cascade sliding mode control applied to a photovoltaic water pumping system with maximum power point tracker. 8th International Symposium on Advanced Electromechanical Motion Systems & Electric Drives Joint Symposium, 2009. ELECTROMOTION 2009. [CrossRef]

- Marouani, R.; Sellami, M.A.; Mami, A. Photovoltaic Water Pumping System Controlled by Cascade Sliding Mode. Research Journal of Applied Sciences, Engineering and Technology,7(20):4364-4369. [CrossRef]

| Equipment (units) | Technical specifications | Power (kW) |

|---|---|---|

| Heat pump | Absorption chiller (NH3/H2O), model GA Line ACF 60-00 of the ROBUR brands | 17.72 |

| Device for oxygenation (2) | AquaOxy 4800 | 0.06 |

| Variable speed control (1) | CHINT NVF2-1.5/TS4 inverter | 0.9 |

| Fan type 1 and 2 (2/1) | THERMIVENT extractors | 0.250/0.05 |

| Controller for irrigation (1) | Hunter X-core controller | 0.010 |

| Centrifugal water pump (2) | DAB, KPS 30/16 M | 0.370 |

| Dosing pump (1) | Green Line Dosatron D25 | 0.01 |

| Lighting fixture (8) | Fluorescent lamp | 0.016 |

| Daily power of the centrifugal pump (kW) | Studied cases |

|---|---|

| 0 | Measured case |

| 0.5 | Simulated case 0.5 |

| 1 | Simulated case 1 |

| 1.5 | Simulated case 1.5 |

| 2 | Simulated case 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).