1. Introduction

Police officers must deal with crime, their institution, legal duties, and citizen ambivalence. Their profession is demanding and complex (Meylan et al. 2009). Moreover, police officers often work under stressful conditions with a heavy workload and strict working time regulations. As public servants who serve the citizen, they should bear the responsibility for maintaining national security and social stability. Their successful of work are not only related to their organizations but also to the success or failure of governing the country (Liu et al. 2019). Gelderen and Bik (2016) research that conducted among policemen, the same context, identified work engagement as one of the most influential antecedents of their successful work. Thus, work engagement among police officers should be improved to help them operate more effectively and protect the citizens.

Police officers are unique profession that requires a high level of work engagement (Liu et al. 2019) but these professionals struggle to sustain job transition and engagement. The difficulties of police employment have increased the projected in-service career transition for officers. Legal, IT, and security issues are addressed in these transition workshops. Other than that, police officers' mobility capital also an interesting antecedents that affects employee engagement (Forrier et al. 2009).

Employee engagement research has grown popular in the management literature (Bakker 2011; Macey & Schneider 2008; Rich et al. 2010; Saks 2006). The literature defines employee engagement as "an individual employee's cognitive, emotional, and behavioral state directed toward desired organizational outcomes" (Shuck & Wollard 2010). Others see it as an excellent psychological condition of motivation that affects discretionary efforts and organizational citizenship (Saks 2006). Employee engagement has been linked to job satisfaction, turnover, innovation, performance, and organizational success (Baumruk, 2006; Buckingham & Coffman 1999; Stumpf et al. 2013).

Saks (2006) defined engagement as “a unique construct of cognitive, emotional and behavioral components associated with individual role performance.” This definition suggests that physical, emotional, and cognitive factors cause employee involvement (Kahn 1990; Schaufeli et al. 2002). Saks (2006) claims that social exchange theory (SET) explains employee engagement well. Saks (2006) believes employee involvement may repay employers. Based on their resources, workers may determine how engaged they want to be with their organization. Recent empirical research focuses on employee engagement. Employee engagement improves organizational success (Robertson & Cooper, 2010; Akingbola & van den Berg 2019; Ali et al. 2020). Several research studies have examined the causes and effects of employee engagement (Saks 2006; Slåtten & Mehmetoglu 2011; Ruck et al. 2017; Saks 2019). However, employee involvement antecedents and effects are seldom studied. (Ugargol and Patrick 2018; Anthony-McMann et al. 2017; Sahu 2017). Identifying the causes and effects of public sector employee engagement since disengaged workers may cause organizational issues, including turnover. Based on the description above, there are the urgency to conduct research related to the antecedents of employee engagement.

2. Literature Review & Hypothesis Development

2.1. Job Transition

Employment transition changes employment status and content significantly (Nicholson 1984). Job transitions might occur internally or outside (Forrier et al. 2015). According to McCall and Hollenbeck (2002) internal job transitions provide workers with additional experience, which boosts their career drive (affective). Employees will also adapt better to corporate changes (Karaevli & Hall 2006). Internal work transitions provide employees with additional experience, which increases their willingness and capacity to adapt their behavior, ideas, and beliefs to meet environmental demands. Based on this, a hypothesis can be drawn, namely:

H1: Internal job transition has a positive effect on movement capital

Inter-organizational mobility affects human capital (knowing-how) and self-awareness (knowing-why), according to Colakoglu (2011). External job changes give employees extra experience to strengthen their cognitive talents and achieve work performance objectives. One method is company-provided training. Employees who face external job transfers will get more experience, boosting their career drive (affective). Based on this, a hypothesis can be drawn, namely:

H2: External job transition has a positive effect on movement capital

2.2. Movement Capital

Movement capital improves mobility (Forrier et al. 2009; Trevor 2001). Forrier et al. (2009) argued that attitudes, skills, knowledge, and competencies impact job mobility, including human capital, social capital, self-awareness, and flexibility. De Fillipi and Arthur (1994) also Inkson and Arthur (2001) define career capital as knowing-how, knowing-why, and knowing-whom. Human capital is an employee's capacity to satisfy employment standards, which may affect career chances. This is connected to knowing how. Arthur and Inkason (2001) claim that social capital improves knowing-how and knowing-whom. Having career-enhancing connections is career capital. Self-awareness guides job choices (McArdle et al. 2007) and suggests possibilities (Fugate et al., 2004). Movement capital motivates (Capellen & Janssens 2005). They know why to explore motivation and personal significance that boosts energy and proactivity (Suutari & Brewster 2003). According to McNeelly and Hall (2008) point out that adaptability is the desire and capacity to modify behavior, ideas, and thoughts in response to external pressures. O'Connell et al (2008) defines adaptability as the capacity to quickly adjust to change, which comprises competence and motivation (Morrison 2002).

2.3. Perceived Employability

Employability covers individual-centered notions (Fugate et al. 2004). A network that refreshes job skills boosts employability (Tu et al. 2003). Career success may be boosted by confidence and optimism in one's capacity to apply abilities to various situations. According to Forrier et al. (2009) referes to mobility capital increases workers' employability. The individual power of movement capital stimulates and allows workers to utilize and extend employment prospects (Thijssen et al. 2008) and promotes work eligibility (Wittekind 2010). Wittekind et al. (2010) claim that employee flexibility (job-hopping) and perceived internal employability are linked. Based on this, a hypothesis can be drawn, namely:

H3: Movement capital has a positive effect on perceived internal employability

Self-aware workers have high external employability, according to Forrier et al. (2009). The more workers have the drive (affective) to live their careers (self-awareness), the more they feel deserving and enthusiastic about acquiring other positions outside this organization. Silva et al. (2022) demonstrate how employee flexibility to corporate changes affects perceived external employability. Based on this, a hypothesis can be drawn, namely:

H4: Movement capital has a positive effect on perceived external employability

2.4. Employee Engagement

Recently popular organizational behavior concepts and employee engagement are a commitment to work success. This is a solid emotional connection between workers and their company that motivates them to work hard (Risher 2010). Tritch (2003) says employee involvement increases contribution and commitment, reducing resignation. Steel and Landon (2011) claim that internal employability helps get employees to commit and advance in the organization. Gallup Management (Seijts & Crim 2006) found that 29% of workers are engaged. Employees are passionate and loyal to their organization. According to Blau (1968) in social exchange theory shows that employee engagement increases if employees believe they have the selling power to work at the current company and that there are career development opportunities. Furthermore, business loyalty is growing. Based on this, a hypothesis can be drawn, namely:

H5: Perceived internal employability has a positive effect on employee engagement

According to Pettman (1973) explain that employee turnover awareness is influenced by the perceived ease of relocating or the number of external alternatives viewed by workers. When some employment is available elsewhere, workers are more likely to switch (Anderson & Milkovich 1980). The employment market has made it easier to transfer positive experiences from alternate displacements, known as displacement cognitions (Griffeth & Horn 1988). De Cuyper et al. (2011) explain that when employees see higher job opportunities in other companies, the company fails to invest in the relationship between employees and managers, resulting in decreased employee commitment.

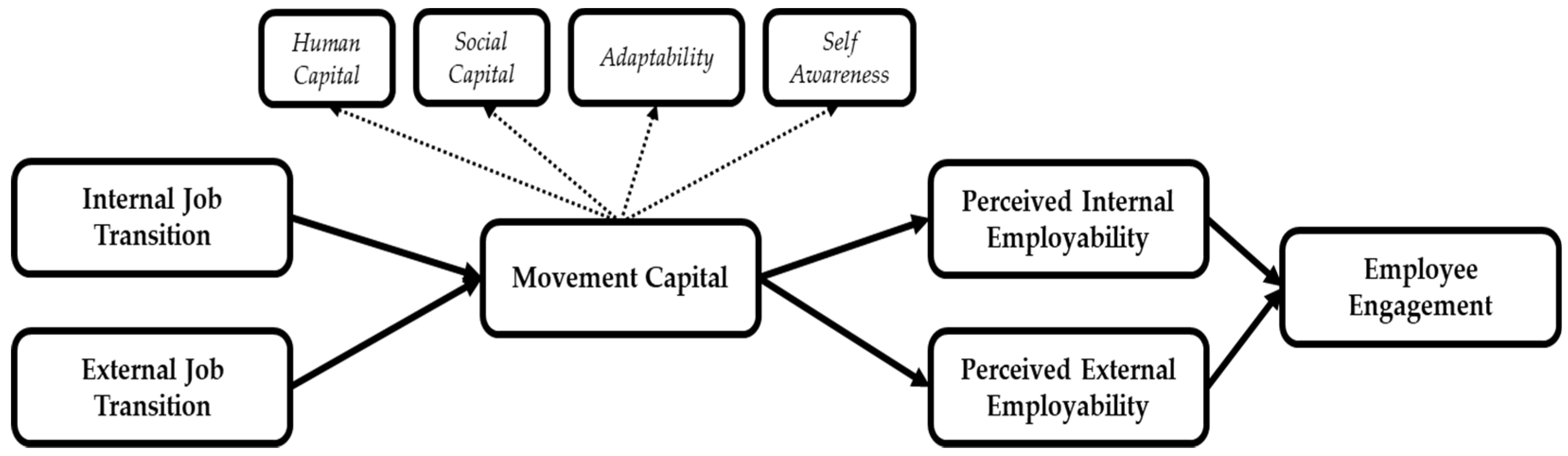

Figure 1 presents a comprehensive research model of this research. Based on this, a hypothesis can be drawn, namely:

H6: Perceived external employability has a negative effect on employee engagement

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Design

The study was conducted using a cross-sectional and ex post facto (non-experimental) methodology. It did not involve any manipulation of variables. The data collection was limited to a single group.

3.2. Participant

In this study, the term "population" refers to the complete set of law enforcement personnel at Tanjung Perak Police Station, totaling 146 individuals located in Surabaya, East Java, Indonesia, as of April 2023. Utilizing a saturated sampling approach, this research involves a census of the entire population to facilitate generalization with minimal errors, aligning with the methodology described by Creswell (2013). Therefore, all 146 Tanjung Perak police officers constitute the sample for this survey. The sample was dominated by men. The sample consisted of 142 Policemen (97.3%) and 4 Policewoman (2.7%). The participants’ ages were from 24 to 55 years. The detailed sample demographics are presented in

Table 1

3.3. Instrument Development

Job Transition Scale used van der Heijden's (2002) 4 item for internal job transition (e.g., “I encountered diverse positional shifts across different departments within the police organization”; “There was an alteration in my current role or assignment, reflecting an internal reassignment within the organization.”) Cronbach’s alpha test for the internal job transition α = 0,828 and AVE = 0,658, Two item for external job transition (e.g., “In the context of policing, I underwent a transition to a higher position or rank outside the current institution.”) external job transition α = 0,935 and AVE = 0,939.

Movement Capital Scale consist of 4-dimension (Human Capital, Self-Awareness, Social Capital, Adaptability). The human capital index uses six Erdoan et al. (2004) items (e.g., “In the context of policing, I possess a diverse array of skills pertinent to my professional duties.”). The self-awareness index uses 8 Jokinen et al. (2008) items (e.g., “I possess a keen awareness of my strengths and weaknesses, as well as a clear understanding of my personal needs and intentions.”). The social capital indicator uses 3 Verbruggen (2012) items (e.g.,” I am acquainted with individuals who are capable of providing assistance in my career advancement.”). The adaptability indicator uses 8 Opperman (1994) item (e.g.,” I demonstrate the proficiency to adjust to shifting situations.”). Cronbach’s alpha test for the Movement Capital obtained values of α = 0,956 and AVE = 0,956.

Perceived Employability Scale used Nelissen et al. (2017) 5 items for Perceived Internal Employee (e.g.,” Within this organization, I am adept at securing employment opportunities that entail job descriptions differing from my current role.”). Cronbach’s alpha test for the Perceived Internal Employee α = 0,836 and AVE = 0,605, also 5 items for Perceived External Employee (e.g.,” I am confident in my ability to swiftly secure a similar position within a different organization.”) Cronbach’s alpha test for the Perceived External Employee α = 0,921 and AVE = 0,759.

Employee Engagement Scale used Saleem et al. (2020) 4 items (e.g.,” I am highly engaged in this organization; This job is all consuming; I am totally into it.”) with Cronbach’s alpha test α = 0,801 and AVE = 0,630.

3.4. Procedure

An examination of scholarly literature was conducted to ascertain the most credible instruments. Following this, a Google Form, incorporating the aforementioned instruments, was developed. Upon the formulation of the questionnaire, it was disseminated via the Google form of the Tanjung Perak Surabaya Indonesia Police Station, facilitating access to a broad participant base. This questionnaire remained accessible from January to March 2023.

4. Results

Structural equation modeling (SEM) via SmartPLS 3.2.9 was employed to evaluate the interrelations in the research model, as delineated by Hair et al. (2017). The choice of SmartPLS was predicated on its adherence to the variance-based SEM methodology, which exhibits reduced sensitivity to sample sizes in comparison to covariance-based SEM tools like AMOS (Analysis of Moment Structures), as noted by Bhattacherjee et al. (2008). This investigation probed the interplay among Job Transition, Movement Capital Scale, Perceived Employability, & Employee Engagement. Consequently, prior to examining the posited linkages, we scrutinized each construct's reliability and validity.

4.1. Reliability and Validity

Table 2 delineates the construct reliability and validity metrics. The factor loadings for each item surpassed the 0.70 benchmark. In a similar vein, the Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability (CR) indices for each construct exceeded the advised threshold of 0.7. Furthermore, the average variance extracted (AVE) for each construct was above the recommended minimum of 0.5, as per Rasool et al. (2019). Reliability of all employed constructs was assessed, along with the ascertainment of convergent validity. We also evaluated discriminant validity, ensuring that the square root of the AVE for each construct exceeded the shared variance amongst constructs. Thus, the scale satisfied both reliability and validity criteria.

4.2. Hypotheses Testing

Presented in

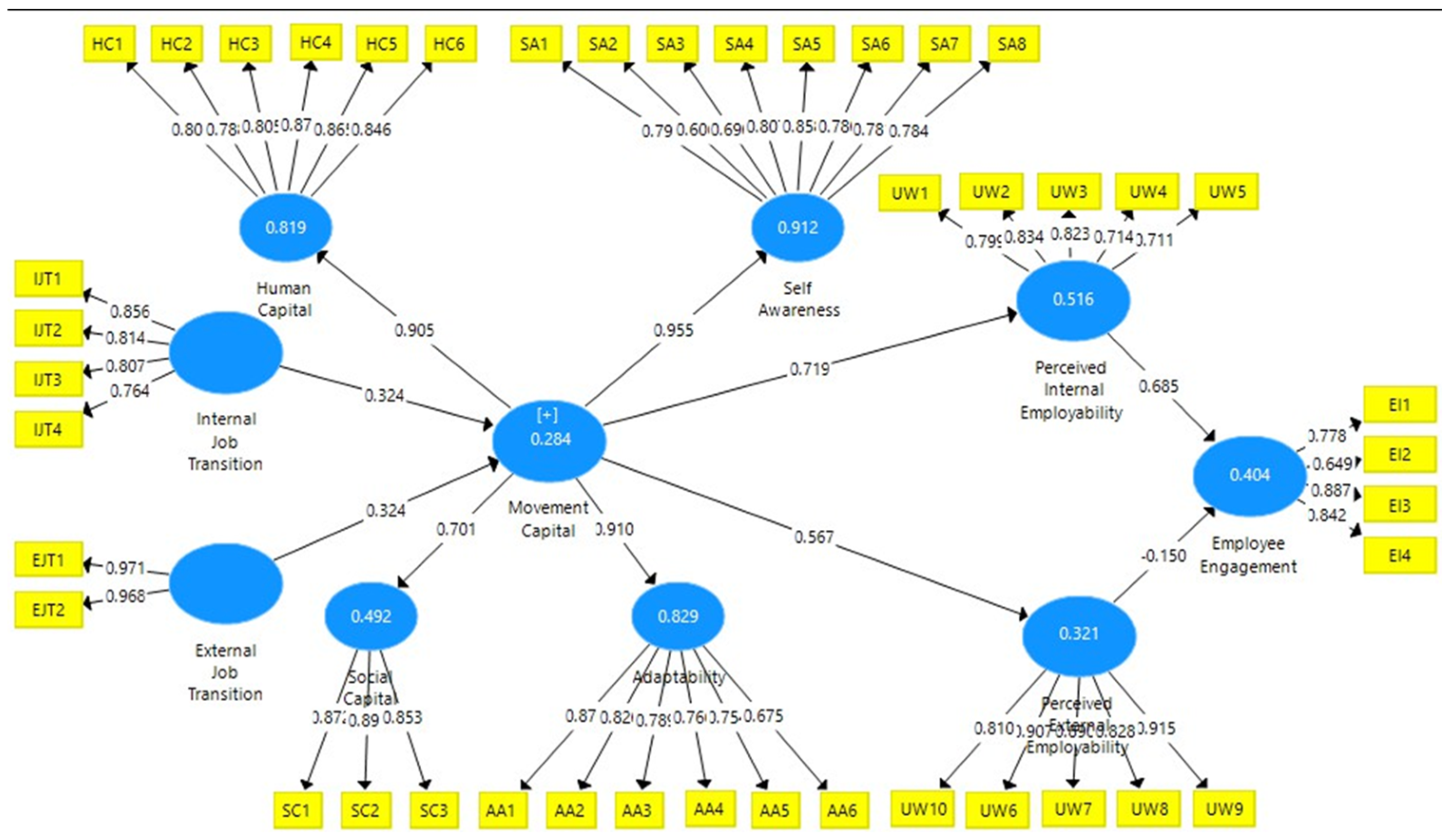

Figure 2 is a structural equation model that delineates the interconnections among constructs such as, Movement Capital which has four dimension, they are Self Awareness, Human Capital, Social Capital, and Adaptability. Next variable is Perceived Internal and External Employability, culminating in Employee Engagement, as observed in a particular cohort, presumably police officers at the Tanjung Perak station.

SEM diagram is a complex representation of a hypothesized model that aims to elucidate the relationships between different personal and job-related factors and how they might influence employability and engagement. The use of SEM suggests that the underlying research is examining the interplay of multiple variables to understand their potential causal relationships within a given theoretical framework. ach latent construct is connected to multiple observed variables, indicated by rectangles, with arrows pointing from the construct to the variable. This suggests that the constructs are theorized to influence these variables. The paths between constructs are also represented with arrows, indicating hypothesized directional relationships. Along these paths, and next to the arrows connecting latent constructs to observed variables, are numerical values, which are likely standardized path coefficients or factor loadings, reflecting the strength and direction of the relationships. Values close to 1 indicate a strong positive relationship, and values closer to 0 indicate a weaker relationship. Several of the constructs also have numbers within the ovals, which could represent the construct reliability or variance explained, reflecting the internal consistency of the construct measurement. Moreover, some paths have plus or minus signs next to them, suggesting that the direction of the relationship (positive or negative) is being explicitly stated in the model. Further detailed explanation can be seen in

Table 3.

The empirical analysis establishes a significantly positive correlation between the internal job transition and the movement capital among police officers at the Tanjung Perak Police Station. Hypothesis 1 suggests a significant positive relationship between internal job transition and movement capital, with a sample effect size of 0.324 and a T-statistic of 3.542, firmly supported by a p-value of 0.000. This correlation indicates that an increase in internal job transitions is associated with heightened movement capital, thereby validating Hypothesis 1. Hypothesis 2 posits a similarly significant positive effect of external job transition on movement capital, indicated by an identical effect size of 0.324 and a slightly higher T-statistic of 3.865, also with a p-value of 0.000. Similarly, external job transitions are positively correlated with movement capital, supporting Hypothesis 2. Hypothesis 3 presents a strong positive impact of movement capital on perceived internal employability, as reflected by a substantial effect size of 0.719, a notable T-statistic of 16.115, and a p-value of 0.000. It means, movement capital shows a positive effect on perceived internal employability, affirming Hypothesis 3, and on perceived external employability, confirming Hypothesis 4. Hypothesis 4 reveals a significant positive effect of movement capital on perceived external employability, shown by an effect size of 0.567, a T-statistic of 12.464, and a p-value of 0.000. Additionally, a higher perceived internal employability positively impacts employee engagement, substantiating Hypothesis 5. Hypothesis 5 indicates a significant positive connection between perceived internal employability and employee engagement, with an effect size of 0.685, T-statistic of 10.152, and a p-value of 0.000. Contrarily, an inverse relationship is observed between perceived external employability and employee engagement, implying that lower external employability perceptions are linked to higher engagement, which also validates Hypothesis 5. Hypothesis 6, contrasting the previous findings, shows a significant negative relationship between perceived external employability and employee engagement, demonstrated by an effect size of -0.150, T-statistic of 2.368, and a p-value of 0.018.

4.3. R-Square

In the goodness of fit assessment, it is by looking at the R-square value generated through. Smart PLS estimation on each path. Based on data processing using the PLS method, the R- square is obtained as follows.

In the path between the Internal and External Job Transition variables on Movement capital, an R-square value of 0.284 is obtained which means that the diversity of employee perceptions of Movement capital can be explained by their perceptions of the Internal and External Job Transition variables of 28.4%. Meanwhile, on the path between the Movement capital variable and Perceived Internal Employability, an R-square value of 0.516 is obtained, which means that the diversity of perceptions of Perceived internal employability can be explained by employee perceptions of the Movement capital variable of 51.6%. In the path between the Movement capital variable and Perceived External Employability, an R-square value of 0.321 is obtained, which means that the diversity of perceptions of Perceived external employability can be explained by employee perceptions of the Movement capital variable of 32.1%. Finally, on the path between Perceived Internal and External Employability of Employee engagement, an R- square value of 0.404 is obtained, which means that the diversity of respondents' perceptions of Employee engagement can be explained by their responses to the Perceived Internal and External Employability variables of 40.4%.

5. Discussion

Hypothesis 1 is in line with the theory of Wittekind et al. (2010) that internal job transition is one of the factors that affect movement capital. This is driven by other factors such as career and skill development, which is the quality of development provided by the company that is more relevant than the number of days an employee participates. Internal job transitions must be able to distinguish whether employees experience upward or lateral displacement. Forrier et al. (2016) argue that there are differences in the impact between the two types on movement capital. When employees experience lateral displacement in the company, employees can use their movement capital, thereby increasing their movement capital. However, if an employee experiences an upward movement in a different division, the employee cannot use all of the movement capital that was previously owned due to different needs in the new division. In the respondents of Police officers in Tanjung Perak Police Station's millennial employees, the largest average is the displacement of different employees but still in the same field, this is a lateral movement so that it has a positive effect on employee capital movement.

Hypothesis 2 is in line with the research of Groot & van den Brink (2000) explaining that human capital theory states that the resources used by employees differ from one company to another. This is interpreted as knowledge, skills, and abilities that are not easily transferred to other organizations (Nicholson 1984). When an employee changes company but works for a different company than before, the employee cannot use all the knowledge, skills, and abilities at the company where the employee is currently working. However, when employees experience a transfer from the same company, the knowledge, skills, and abilities in the previous company can be used in the company where they work today.

Hypothesis 3 is in line with previous research, namely when individuals feel that they have an increasing career, they will feel worthy to work in the company where they work (Kalyal et al. 2010). The higher the movement capital, which consists of human capital, self-awareness, social capital, and adaptability, the employees of Police officers in Tanjung Perak Police Station will feel more confident that they have high internal employability perceived by employees. Companies offer internal opportunities to employees by increasing strong capital movements to bind talented workers to the organization (Dries & Peppermans 2008; Abbas et al. 2023). If employees have low movement capital, Police officers in Tanjung Perak Police Station will develop their movement capital so that employees can increase their movement capital. In accordance with the results of research from Nelissen et al. (2007) that career development becomes a paradox for companies. With the career development obtained, it will increase the movement capital of employees.

Hypothesis 4 is in line with previous research, perceived internal employability can reduce employees' desire to change companies (March & Simon 1958; Kammeyer-Mueler et al. 2005; Steel and Landon 2011). The results of the current study state that there is an influence between the employee's perception of eligibility to get another job and the intention to change companies. The perceived retention effect of internal workability depends on factors such as the employee's career goals, fit of people in the job or adaptability (Forrier et al. 2009). In addition, different forms of future opportunities, for example, upward or lateral, can influence different decisions on intention to move (Nellisen et al. 2017).

Hypothesis 5 is in line with previous research. Factors that influence employee engagement are salary, individual recognition, flexible work schedules, and career advancement (Atapattu & Huybers 2022). There are several factors that increase employee engagement, such as senior behavior, challenges, partner relationships, etc. Engaged employees tend to be in control of their work situations (Gupta & Sharma 2016; Moodley 2012) states that they are happier, more productive, competitive and provide higher level of customer service than others (Nienaber & Martins 2015). Employees with high SPEs are proactive, focus on career advancement (Coetzee et al. 2015) and experience fewer BO symptoms (Lu et al. 2016).

Hypothesis 6 is in line with research by Kalyal et al. (2010) which states that employability is a subjective perception of whether employees' experience allows them to find new jobs in other companies; Such uncertainty affects their job involvement (Kalyal et al. 2010; Berntson et al. 2006). Employees with high employability tend to experience more psychological stress than employees with low employability have different perceptions about their involvement with it; when employees have higher employability in other companies, the negative correlation to employee engagement is stronger than between employees with a lower perceived employability or employees with a perceived good workability in the company. Employees with low employability are fortunate enough to keep their jobs, regardless of the psychological pressure caused by their professional activities, so they tend to maintain their job involvement (employee engagement) (Ekowati et al. 2023; Bufquin et al. 2021).

6. Conclusion

In the realm of occupational research, it has been deduced from empirical evidence that internal job transitions significantly bolster movement capital among officers. Similarly, transitions to external roles manifest comparable positive effects. Further, movement capital exerts a substantial impact on the officers' self-assessed internal and external employability. In the domain of workplace engagement, an interesting dichotomy emerges: while the perception of internal employability positively correlates with increased engagement, perceptions of external employability inversely affect such engagement levels. These findings offer a nuanced understanding of the interplay between job mobility, perceived employability, and resultant employee engagement.

The study's findings elucidate the complex dynamics of job transition and employee engagement within the police force. Internal job transitions that foster career development and skill enhancement significantly contribute to an officer's movement capital, reinforcing their adaptability and commitment to the organization. Perceived employability, both internal and external, plays a dual role, with internal perceptions bolstering engagement and external perceptions potentially diminishing it due to the allure of opportunities outside the current institution. These insights suggest a nuanced relationship between an officer's career development within the force, their perception of external opportunities, and their overall engagement and loyalty to their organization. This highlights the importance of internal growth opportunities for maintaining high levels of employee engagement, while also recognizing the potential disengagement risks posed by external employability

The theoretical benefits of this study lie in its contribution to the understanding of employee engagement within law enforcement, particularly regarding the roles of job transition and movement capital. It extends existing theories by contextualizing them in the unique environment of police work. Practically, the findings offer insights for police departments in managing and enhancing officer engagement through career development strategies. It underscores the significance of internal transitions and movement capital in boosting job satisfaction and commitment, which are essential for maintaining a motivated and efficient police force.

Increasing work engagement through establishing employability can be encouraged by providing training to all lines of the organization. Training design must be more adapted to workplace realities and consider the characteristics of organizational members more inclusively. Recommended training includes digitalization for operational positions, communicating career development for managerial positions (Guillaume and Loufrani-Fedida, 2023) and strengthen the professional identity through increasing internal motivation to improve their desire to engage in their work (Liu et al. 2019). This study thereby provides a foundation for future research and practical applications in similar high-stress public service sectors.

7. Limitations and Future Research

The study's limitations include a narrow demographic focus, restricting findings to police officers at a specific station, which may not be representative of broader populations. The cross-sectional design also limits causal interpretations, and the singular sector examination overlooks potentially distinct dynamics in different organizational settings. To address these gaps, future research should employ a longitudinal approach, encompass a diverse range of participants from various sectors, including management levels, and explore additional factors influencing employee engagement to enhance the robustness and transferability of the findings.

Subsequent inquiries should broaden the participant spectrum, extending beyond factory settings to include managerial positions, which would enrich the existing corpus of knowledge concerning the antecedents of employee engagement with a more granular approach. Additionally, considering the vast array of factors influencing employee engagement, future studies are advised to pinpoint and scrutinize other variables that directly impact organizational engagement. Lastly, while current investigations are confined to business entities, it is imperative that forthcoming research encompasses governmental sectors to affirm and extend the applicability of these findings.

Author Contributions

M.G.T. and I.F.A. were instrumental in conceptualizing the research idea and drafting the manuscript. Supervisory guidance for the study was provided by F.E.N., D.W.H. and P.T.B. The literature review was collaboratively undertaken by M.G.T. and P.T.B., while F.E.N. and E.S.P was responsible for developing the research methodology. The interpretation of data was carried out by I.F.A and F.N.D. Each author contributed to the critical reading and approval of the final manuscript. Furthermore, all authors have concurred with and endorsed the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The research ethics committee of Postgraduate School of Universitas Airlangga and, it was survey-based research.

Informed Consent Statement

Consent for participating in the questionnaire survey was obtained telephonically from the research participants. These individuals were identified via their supervisors and voluntarily completed the questionnaires. Additionally, this study does not include any potentially identifiable images of human subjects.

Data Availability Statement

The data pertaining to this study can be made accessible upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their profound gratitude to the Kepolisian Republik Indonesia (POLRI) for their invaluable support and cooperation, which significantly contributed to the success of this research. Additionally, sincere appreciation is also directed towards the Sekolah Pascasarjana of Universitas Airlangga for their academic guidance and resources that were instrumental in the completion of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors affirm that there are no conflicts of interest associated with this research

References

- Abbas, A. , Ekowati, D., Suhariadi, F., & Anwar, A. Human capital creation: A collective psychological, social, organizational and religious perspective. Journal of Religion and Health. [CrossRef]

- Akingbola, K. , & Van Den Berg, H. A. Antecedents, consequences, and context of employee engagement in nonprofit organizations. Review of Public Personnel Administration 2019, 39, 46–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H. Y. , Asrar-ul-Haq, M., Amin, S., Noor, S., Haris-ul-Mahasbi, M., & Aslam, M. K. Corporate social responsibility and employee performance: The mediating role of employee engagement in the manufacturing sector of Pakistan. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 2020, 27, 2908–2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J. C. , & Milkovich, G. T. Propensity to leave: A preliminary examination of March and Simon’s model. Relations industrielles 1980, 35, 279–294. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony-McMann, P. E. , Ellinger, A. D., Astakhova, M., & Halbesleben, J. R. Exploring different operationalizations of employee engagement and their relationships with workplace stress and burnout. Human Resource Development Quarterly 2017, 28, 163–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atapattu, M. M. , & Huybers, T. Motivational antecedents, employee engagement and knowledge management performance. Journal of Knowledge Management 2022, 26, 528–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B. An evidence-based model of work engagement. Current directions in psychological science 2011, 20, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumruk, R. Why managers are crucial to increasing engagement: Identifying steps managers can take to engage their workforce. Strategic HR Review 2006, 5, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berntson, E. , Näswall, K., & Sverke, M. Investigating the relationship between employability and self-efficacy: A cross-lagged analysis. European journal of work and organizational psychology 2008, 17, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacherjee, A. , Perols, J., & Sanford, C. Information technology continuance: A theoretic extension and empirical test. Journal of Computer Information Systems 2008, 49, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P. M. Social exchange. International encyclopedia of the social sciences 1968, 7, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckingham, M. A. R. C. U. S. , & Coffman, C. 1999. Break all the rules, London: Simon & Shuster.

- Bufquin, D. , Park, J. Y., Back, R. M., de Souza Meira, J. V., & Hight, S. K. Employee work status, mental health, substance use, and career turnover intentions: An examination of restaurant employees during COVID-19. International Journal of Hospitality Management 2021, 93, 102–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cappellen, T. , & Janssens, M. Career paths of global managers: Towards future research. Journal of World Business 2005, 40, 348–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coetzee, M. , & Stoltz, E. Employees' satisfaction with retention factors: Exploring the role of career adaptability. Journal of Vocational Behavior 2015, 89, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colakoglu, S. N. The impact of career boundarylessness on subjective career success: The role of career competencies, career autonomy, and career insecurity. Journal of Vocational Behavior 2011, 79, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W. 2002. Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, And Evaluating Quantitative. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- De Cuyper, N. , Mauno, S., Kinnunen, U., & Mäkikangas, A. The role of job resources in the relation between perceived employability and turnover intention: A prospective two-sample study. Journal of Vocational Behavior 2011, 78, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dries, N. , Pepermans, R., & Carlier, O. Career success: Constructing a multidimensional model. Journal of Vocational Behavior 2008, 73, 254–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekowati, D. , Abbas, A., Anwar, A., Suhariadi, F., & Fahlevi, M. Engagement and flexibility: An empirical discussion about consultative leadership intent for productivity from Pakistan. Cogent Business & Management 2023, 10, 2196041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrier, A. , Sels, L., & Stynen, D. Career mobility at the intersection between agent and structure: A conceptual model. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 2009, 82, 739–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrier, A. , Verbruggen, M., & De Cuyper, N. Integrating different notions of employability in a dynamic chain: The relationship between job transitions, movement capital and perceived employability. Journal of Vocational Behavior 2015, 89, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fugate, M. , Kinicki, A. J., & Ashforth, B. E. Employability: A psycho-social construct, its dimensions, and applications. Journal of Vocational Behavior 2004, 65, 14–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelderen, B. R. , & Bik, L. W. Affective organizational commitment, work engagement and service performance among police officers. Policing International Journal. 2016, 39, 206–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffeth, R. W, & Horn, P. W. A comparison of different conceptualizations of perceived alternatives in turnover research. Journal of Organizational Behavior 1988, 9, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groot, W., & van den Brink, H. M. 2000. Job satisfaction, wages and allocation of men and women. In Advances in Quality of Life Theory and Research, Springer, Dordrecht, pp. 111-128. [CrossRef]

- Guillaume, M. and Loufrani-Fedida, S. Stakeholder engagement in inclusive employability management for employees whose health at work is impaired: Empirical evidence from a French public organization. Personnel Review 2023, 52, 121–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N. , & Sharma, V. Exploring employee engagement—A way to better business performance. Global Business Review 2016, 17, 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. , Hollingsworth, C. L., Randolph, A. B., & Chong, A. Y. L. An updated and expanded assessment of PLS-SEM in information systems research. Industrial Management & Data Systems 2017, 117, 442–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inkson, K. , & Arthur, M. B. 2001. How to be a successful career capitalist, Organizational Dynamics.

- Jokinen, T. , Brewster, C., & Suutari, V. Career capital during international work experiences: Contrasting self-initiated expatriate experiences and assigned expatriation. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 2008, 19, 979–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyal, H. J. , Berntson, E., Baraldi, S., Näswall, K., & Sverke, M. The moderating role of employability on the relationship between job insecurity and commitment to change. Economic and Industrial Democracy 2010, 31, 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D. , Wanberg, C. R., Glomb, T. M., & Ahlburg, D. The role of temporal shifts in turnover processes: It's about time. Journal of Applied Psychology 2005, 90, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karaevli, A. , & Hall, D. T. T. How career variety promotes the adaptability of managers: A theoretical model. Journal of Vocational Behavior 2006, 69, 359–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T. , Zeng, X., Chen, M. and Lan, T. The Harder You Work, the Higher Your Satisfaction With Life? The Influence of Police Work Engagement on Life Satisfaction: A Moderated Mediation Model. Frontier in Psychology. 2019, 10, 826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, L. , Lu, A. C. C., Gursoy, D., & Neale, N. R. Work engagement, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions: A comparison between supervisors and line-level employees. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 2016, 28, 737–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macey, W. H. , & Schneider, B. The meaning of employee engagement. Industrial and Organizational Psychology 2008, 1, 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- McArdle, S. , Waters, L., Briscoe, J. P., & Hall, D. T. T. Employability during unemployment: Adaptability, career identity, and human and social capital. Journal of Vocational Behavior 2007, 71, 247–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCall Jr, M. W. , & Hollenbeck, G. P. 2002, Developing global executives: The lessons of international experience.

- Meylan, S. , Boillat, P., & Morel, A. Épuisement professionnel en contexte policier: Le rôle des valeurs. Éthique publique. Revue internationale d’éthique sociétale et gouvernementale 2009, 11, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moodley, N. 2012. Employees’ perceptions of whether monetary rewards would motivate those working at a State Owned Enterprise to perform better. Doctoral dissertation, University of Pretoria. https://repository.up.ac.za/bitstream/handle/2263/26772/dissertation.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- Morrison, E. W. Newcomers' relationships: The role of social network ties during socialization. Academy of Management Journal 2002, 45, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelissen, J. , Forrier, A. , & Verbruggen, M. Employee development and voluntary turnover: Testing the employability paradox. Human Resource Management Journal 2017, 27, 152–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, N. 1984. A theory of work role transitions. Administrative Science Quarterly. [CrossRef]

- Nienaber, H. , & Martins, N. Validating a scale measuring engagement in a South African context. Journal of Contemporary Management 2015, 12, 401–425. [Google Scholar]

- O'Connell, D. J. , McNeely, E., & Hall, D. T. Unpacking personal adaptability at work. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies 2008, 14, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppermann, R. Adaptively supported adaptability. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 1994, 40, 455–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettman, B. O. Some factors influencing labour turnover: A review of research literature. Industrial Relations Journal 1973, 4, 43–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, B. L. , Lepine, J. A., & Crawford, E. R. Job engagement: Antecedents and effects on job performance. Academy of Management Journal 2010, 53, 617–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risher, H. 2010. Don't overlook frontline supervisors. Public Manager.

- Robertson, I. T. , & Cooper, C. L. Full engagement: The integration of employee engagement and psychological well-being. Leadership & Organization Development Journal 2010, 31, 324–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruck, K. , Welch, M., & Menara, B. Employee voice: An antecedent to organisational engagement? Public Relations Review 2017, 43, 904–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saks, A. M. 2006. Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement. Journal of Managerial Psychology. [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B. , Salanova, M., González-Romá, V., & Bakker, A. B. The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies 2002, 3, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seijts, G. H. , & Crim, D. What engages employees the most or, the ten C’s of employee engagement. Ivey Business Journal 2006, 70, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Shuck, B. , & Wollard, K. Employee engagement and HRD: A seminal review of the foundations. Human Resource Development Review 2010, 9, 89–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R. , Dias, Á., Pereira, L., da Costa, R. L., & Gonçalves, R. Exploring the direct and indirect influence of perceived organizational support on affective organizational commitment. Social Sciences 2022, 11, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, H. , & March, J. 2015. Administrative behavior and organizations. In Organizational Behavior. Routledge 2: 41-59.

- Slåtten, T. and Mehmetoglu, M. Antecedents and effects of engaged frontline employees: A study from the hospitality industry. Managing Service Quality: An International Journal 2011, 21, 88–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stumpf, S. A. , Tymon Jr, W. G., & van Dam, N. H. Felt and behavioral engagement in workgroups of professionals. Journal of Vocational Behavior 2013, 83, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suutari, V. , & Brewster, C. Repatriation: Empirical evidence from a longitudinal study of careers and expectations among Finnish expatriates. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 2003, 14, 1132–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thijssen, J. G. , Van der Heijden, B. I., & Rocco, T. S. Toward the employability—Link model: Current employment transition to future employment perspectives. Human Resource Development Review 2008, 7, 165–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevor, C. O. Interactions among actual ease-of-movement determinants and job satisfaction in the prediction of voluntary turnover. Academy of Management Journal 2001, 44, 621–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, H. S. , Forret, M. L., & Sullivan, S. E. The Awakening Dragon: An Examination of the Relationship between Firm Type and Career Outcomes of Chinese Managers. Southern Management Association 2003 Meeting: 286.

- Ugargol, J. D. , & Patrick, H. A. The relationship of workplace flexibility to employee engagement among information technology employees in India. South Asian Journal of Human Resources Management 2018, 5, 40–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Heijden, B. Prerequisites to guarantee life-long employability. Personnel Review 2002, 31, 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbruggen, M. Psychological mobility and career success in the ‘new’ career climate. Journal of Vocational Behavior 2012, 81, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittekind, A. , Raeder, S., & Grote, G. A longitudinal study of determinants of perceived employability. Journal of Organizational Behavior 2010, 31, 566–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).