1. Introduction

Cerebral palsy (CP) is the most common health condition that produces motor disability in childhood and is one of the largest participant groups in para-sport [

1]. Considering that football is one of the most popular sports worldwide, this discipline is widely practiced at a variety of competitive levels [

2]. CP football is an expression of the regular sport, dedicated exclusively to players with CP and other related health conditions of brain injuries generating mild impairments of hypertonia, ataxia, or dyskinesia [

3]. The professionalization of para-sport has increased the attraction of researchers studying the different factors that influence performance and improving the data to support the preparation of athletes with disabilities. Over the last decade, a significant number of studies have provided insight into the physical and physiological responses of football players with CP, offering a framework for performance and training [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Although most of the literature is focused on the performance of para-footballers, scarce information is available regarding referees, generating a gap in current knowledge when considering the personnel responsible for regulating the competition.

Referees who officiate international level CP football matches supervise the application of minimal adaptation rules to allow the competition with modifications to include the field size, the number of players, no off-side law, small sized goals (i.e., 2m x 5m), permitting a throw-in with one hand, reduced game time, and a classification system that determines player participation according to the impact of the impairment in football skills [

8]. Although people with CP reported lower physical performance compared to the able-bodied population [

9], the para-footballers running activity profile during competitions can reach considerable requirements of high-intensity actions [

4,

5,

6,

7], an aspect that referees should be physically prepared to face in this sport. Similar to regular football, CP football matches require a field referee and two assistant referees to supervise the game and ensure optimal positioning to facilitate decision-making, considering the specific impairment characteristics of the players and modifications of the para-sport [

10]. Early studies in CP football reported a higher prevalence of goals scored per match compared to non-impaired competitions (e.g., 5 goals vs. 2 goals), which may be attributed to differences in field size, functional profiles, and contextual factors that can influence the final result of a match, and therefore the physical performance of the referee is crucial for the decisions on the game [

8,

11,

12]. Referees of regular football move approximately 10 km during matches, of which almost 3 km are covered at a high intensity (over 13 km/h-1) necessary to follow the game situation, make adequate decisions, and respond to the physical demands of the match [

10,

13,

14,

15], however, to date, little research has reported the physical responses of referees officiating CP football matches.

Currently, CP football presents a structured program of competition including world and regional tournaments divided by the level of performance, providing for ever increasing professionalization of the environments in accordance with the rising participation of para-footballers [

16]. Due to the implications of the referee decisions in the outcome of the game and the relevant role played in football [

12], a deeper understanding of the running capacities of referees of CP football may support the characterization of the responses encountered during competitive matches and support referee mentors and coaches to implement optimal training programs. Therefore, the aim of this study was 1) to describe and compare the physical responses between World Cup and World Championships tournaments in referees of CP football. 2) to compare the referees’ physical responses between the 1st and 2nd halves.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Thirteen international referees (39.17 ± 8.26 yr; 76.07 ± 13.39 kg; 174.04 ± 9.97 cm; 24.99 ± 3.28 kg/m2) from three continents and 11 different nationalities who officiated the men’s 2022 World Cup (participation of teams between world ranking 1st to 15th held in Salou, Spain) and 2022 World Championships (participation of teams between world ranking 16th to 30th held in Olbia, Italy), voluntarily participated in this study. Of the total participants, 10 were men (40.22 ± 8.20 yr; 80.32 ± 10.07 kg; 176.70 ± 6.45 cm; 25.74 ± 3.22 kg/m2; World Cup = 6; World Championships = 5) and 3 were women (36.00 ± 5.89 yr; 61.90 ± 10.84 kg; 165.17 ± 12.52 cm; 22.50 ± 0.76 kg/m2; World Cup = 2; World Championships = 2), with 18.62 ± 9.24 and 6.54 ± 4.22 years of experience refereeing regular football and CP football respectively. Of the total participants, 8 officiated World Cup matches (37.13 ± 6.53 yr; 80.46 ± 13.09 kg; 175.50 ± 10.73 cm; 26.06 ± 3.59 kg/m2) and 7 officiated World Championships matches (43.83 ± 8.64 yr; 73.33 ± 12.70 kg; 173.36 ± 8.48 cm; 24.30 ± 3.13 kg/m2). Two referees were able to participate in both tournaments. All of the evaluated referees did not present any eligible impairments. In addition, all were informed about the study protocols and gave their informed consent to take part in this study. This investigation was approved by the Ethics Committee of the principal investigator’s university (reference no. DPS.RRV.03.17).

2.2. Procedures

A cross-sectional design was used to determine the physical responses to compare the 1st and 2nd halves and analyze the performance between the different tournaments, recording physical variables throughout the matches. Data was collected for 15 independent referee observations extracted from 49 valid matches played between 09:00 to 18:00 hours in the world competitions. For the comparison between tournaments, 31 observations (game time = 68.76 ± 8.41 min) in 8 international referees and 18 observations (game time = 66.85 ± 8.50 min) in 7 international referees were included for the World Cup and World Championships, respectively. All the referees used vests designed to wear a global positioning system (GPS) device to monitor the physical responses. In preparation for the matches, participants avoided any type of extenuating exercise and performed a standardized 15-minute warm-up. The matches were played in two different venues on artificial turf with a field size of 50 m x 70 m.

2.3. Measures

Match running performance was recorded using GPS devices (WIMU PROTM, RealTrack System SL, Almería, Spain), sampling at a frequency of 10 Hz. A previous study reported the validity and reliability of this device to assess physical performance [

17] which was used in able-bodied football players [

18], football players with CP [

19], and referees of regular football [

20]. Before the official matches, the devices were activated and synchronized according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. All the collected data were extracted using S PROTM software (RealTrack Systems, Almeria, Spain). The participants wore a GPS unit inserted in a purpose-built harness secured between the upper scapula with a fitted body vest. The variables considered for the analysis were described in each match half and match total time: total distance (TD) covered, explosive distance (ED; total distance covered with an acceleration above 1.12 m/s2: m) [

20], maximum speed (km/h), distance covered at different speeds (Walking [W]: 0–6 km/h; Jogging [J]: 6–12 km/h; Medium intensity running [MIR]: 12–18 km/h; High intensity running [HIR]: 18–21 km/h; Sprinting [SPR]: 21–24 km/h; and Maximum sprinting [MS]: > 24 km/h) [

19], high-intensity breaking distance (HIBD: distance decelerating > 2 m/s2), total number of sprints (n), sprinting distance (m), high-speed running distance (HSRD; > 15.1 km/h: m), high-speed running actions (HSRA: n) [

21]. Moreover, the total number of accelerations (ACC) and decelerations (DEC; n) (where an acceleration or deceleration is deemed to be any increase or reduction in speed that means passing or descending from the zero axis), maximal acceleration (ACCMax: m/s2), and maximal deceleration (DECMax: m/s2) were registered [

20]. In addition, the distance covered accelerating by zones (Z1: 0-1 m/s2; Z2: 1-2 m/s2; Z3: 2-3 m/s2; Z4: >3 m/s2), and distance covered decelerating by zones (Z1: 0-1 m/s2; Z2: 1-2 m/s2; Z3: 2-3 m/s2; Z4: >3 m/s2) were considered for the analysis [

22]. Finally, the player load (PL) was used and represented in arbitrary units (AU) [

18].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Normal distribution and homogeneity of variances were tested using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Levene tests. Student’s t-test for independent samples were performed to evaluate mean referees’ physical response differences between the World Cup and World Championships. Student’s t-test for paired samples was performed in order to evaluate mean differences between the 1st and 2nd half of CP football referees’ physical responses. Practical significance was assessed by Cohen’s d [

23], with values of above 0.8, between 0.8 and 0.5, between 0.5 and 0.2, and lower than 0.2 being considered large, moderate, small, and trivial, respectively. The 95% confidence intervals of the effect sizes were calculated with their respective upper and lower boundaries. Data analyses were performed using JASP (JASP for Windows, version 0.13, Amsterdam, Netherlands) and the Statistical Package for Social Sciences for Windows (version 24.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

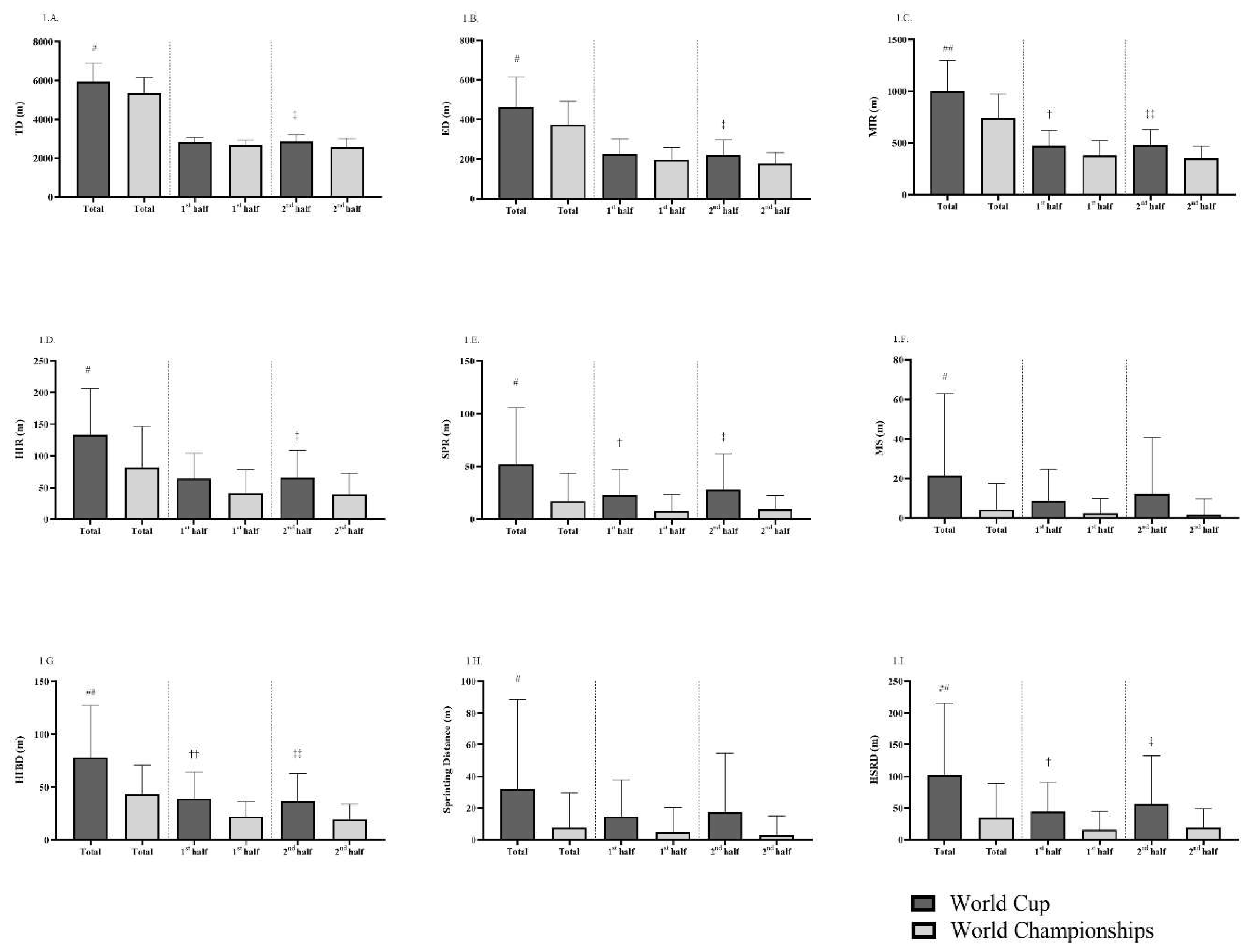

Regarding the comparison of the physical response of field referees during the different competitions (

Figure 1), the TD and ED values were higher in the World Cup in both the total time (p < 0.05; d = 0.62 to 0.65; moderate) and 2nd half (p < 0.05; d = 0.62 to 0.72; moderate) and maximum speed values were higher in total time (p = 0.01; d = 0.80; large), 1st half (p < 0.01; ES = 0.90; large), and 2nd half (p = 0.03; d = -0.67; moderate). In addition, referees reported a higher distance in the total time, 1st half and 2nd half at MIR (p < 0.05; d = 0.67 to 0.93; moderate to large), SPR (p < 0.05; d = 0.67 to 0.76; moderate), HIBD (p < 0.01; d = 0.77 to 0.81; moderate to large), HSRD (p < 0.05; d = 0.59 to 0.71; moderate) and number of HSRA (p < 0.05; d = 0.55 to 0.67; moderate) in World Cup matches compared to World Championships matches. Similarly, a greater distance was covered in World Cup matches as compared to the World Championships matches at HIR in total time and 2nd half (p < 0.05; d = 0.68 to 0.74; moderate), MS in total time (p < 0.05; d = 0.50; moderate), number of sprints in total time and 2nd half (p < 0.05; d = 0.52; moderate), and sprinting distance in overall time (p < 0.05; d = 0.52; moderate).

Table 1 shows the total distance covered, maximum speed, and distance covered at different intensities, as well as the differences between both halves of the World Cup and World Championships. The results showed no significant differences in physical responses between the 1st and 2nd halves of the played matches (p > 0.05; d = 0.06 to -0.28; trivial to small) when considering all the tournaments and only significant differences between the 1st and 2nd half were found in the distance covered at J intensity in the World Championships (p = 0.03; d = 0.55; moderate) being higher in the 1st halves. No significant differences were observed between 1st and 2nd halves in World Cup matches.

Table 1.

Physical response variables by referees in cerebral palsy football matches related to the total distance covered, maximum speed, and distance covered at different intensities in both World Cup and World Championships halves.

Table 1.

Physical response variables by referees in cerebral palsy football matches related to the total distance covered, maximum speed, and distance covered at different intensities in both World Cup and World Championships halves.

| |

Total Sample (n = 13 referees, 49 observations) |

|

World Cup (n = 8 referees, 31 observations) |

World Championships (n = 7 referees, 18 observations) |

| Variables |

Total |

1st half |

2nd half |

d (95% CI) |

Total |

1st half |

2nd half |

d (95% CI) |

Total |

1st half |

2nd half |

d (95% CI) |

| TD (m) |

5731.82 ± 950.00 |

2774.90 ± 264.90 |

2753.66 ± 413.67 |

0.07

(-0.21, 0.35) |

5950.98 ± 970.83 |

2828.40 ± 264.14 |

2857.33 ± 362.73 |

-0.12

(-0.47, 0.24) |

5354.37 ± 804.07 |

2682.77 ± 246.57 |

2575.11 ± 444.55 |

0.27

(-0.21, 0.73) |

| ED (m) |

430.11 ± 144.29 |

213.79 ± 71.83 |

203.30 ± 72.98 |

0.24

(-0.05, 0.52) |

461.85 ± 151.28 |

224.76 ± 74.60 |

219.38 ± 77.06 |

0.13

(-0.23,0.48) |

375.43 ± 115.73 |

194.89 ± 64.44 |

175.61 ± 57.21 |

0.41

(-0.08, 0.89) |

Max speed

(km·h) |

22.04 ±

2.69 |

22.96 ± 2.91 |

22.10 ±

2.83 |

0.08

(-0.21, 0.36) |

22.79 ± 2.61 |

23.14 ± 2.75 |

22.78 ± 2.82 |

0.16

(-0.19, 0.52) |

20.76 ± 2.38 |

20.73 ± 2.58 |

20.95 ± 2.52 |

-0.14

(-0.60, 0.33) |

| Distance at different intensities |

| W (m) |

2591.58 ± 288.54 |

1242.56 ± 122.30 |

1260.17 ± 171.94 |

-0.14

(-0.42, 0.15) |

2606.57 ± 310.76 |

1238.86 ± 106.34 |

1261.29 ± 129.06 |

-0.24

(-0.59, 0.12) |

2565.75 ± 504.69 |

1248.92 ± 149.02 |

1258.25 ± 232.53 |

-0.05

(-0.51, 0.41) |

| J (m) |

2066.24 ± 518.78 |

1013.38 ± 179.34 |

974.32 ± 231.76 |

0.26

(-0.03, 0.54) |

2136.85 ± 570.34 |

1018.44 ± 192.78 |

1009.25 ± 219.04 |

0.07

(-0.29, 0.42) |

1944.63 ± 401.40 |

1004.67 ± 158.42 |

914.16 ± 246.84 |

0.55

(0.04, 1.04)* |

| MIR (m) |

905.62 ± 303.00 |

439.74 ± 151.73 |

433.43 ± 150.58 |

0.05

(-0.23, 0.33) |

1000.96 ± 300.90 |

475.64 ± 146.61 |

480.42 ± 148.62 |

-0.04

(-0.39, 0.31) |

741.42 ± 233.08 |

377.91 ± 143.80 |

352.51 ± 118.65 |

0.20

(-0.27, 0.66) |

| HIR (m) |

114.22 ± 74.64 |

55.28 ± 40.31 |

56.12 ±

41.59 |

-0.02

(-0.30, 0.26) |

133.48 ± 73.64 |

63.66 ± 40.19 |

66.01 ± 42.92 |

-0.06

(-0.41, 0.29) |

81.06 ± 65.72 |

40.86 ± 37.25 |

39.08 ± 33.88 |

0.06

(-040, 0.53) |

| SPR (m) |

39.04 ±

48.28 |

17.37 ± 22.19 |

21.20 ±

29.29 |

-0.20

(-0.48, 0.09) |

51.73 ± 53.62 |

22.85 ± 23.85 |

28.15 ± 33.76 |

-0.23

(-0.59, 0.13) |

17.18 ± 26.63 |

7.94 ± 15.44 |

9.24 ± 13.10 |

-0.12

(-0.59, 0.34) |

| MS (m) |

15.13 ±

34.61 |

6.57 ± 13.54 |

8.42 ±

23.57 |

-0.11

(-0.39, 0.17) |

21.39 ± 41.33 |

8.95 ± 15.65 |

12.22 ± 28.50 |

-0.16

(-0.52, 0.19) |

4.33 ± 13.12 |

2.47 ± 7.55 |

1.87 ± 7.94 |

0.07

(-0.39, 0.53) |

| HIBD (m) |

65.02 ±

45.65 |

32.98 ± 22.93 |

30.40 ±

23.85 |

0.22

(-0.06, 0.51) |

77.83 ± 49.27 |

39.16 ± 24.92 |

36.77 ± 26.08 |

0.18

(-0.18, 0.54) |

42.96 ± 28.02 |

22.34 ± 14.13 |

19.43 ± 14.28 |

0.36

(-0.12, 0.83) |

| Sprints (n) |

1.33 ±

2.54 |

0.67 ± 1.33 |

0.63 ±

1.44 |

0.04

(-0.24, 0.32) |

1.84 ± 2.95 |

0.90 ± 1.47 |

0.90 ± 1.68 |

0.00

(-0.35, 0.35 |

0.44 ± 1.29 |

0.28 ± 0.96 |

0.17 ± 0.71 |

0.10

(-0.36, 0.57) |

| Sprinting distance (m) |

23.04 ±

48.12 |

10.81 ± 21.31 |

11.98 ±

31.16 |

-0.05

(-0.33, 0.23) |

32.06 ± 56.61 |

14.37 ± 23.52 |

17.30 ± 37.32 |

-0.11

(-0.46, 0.24) |

7.51 ± 21.89 |

4.68 ± 15.56 |

2.83 ± 12.00 |

0.11

(-0.36, 0.57) |

| HSRA (n) |

4.41 ±

5.13 |

1.94 ± 2.32 |

2.41 ±

3.17 |

-0.21

(0.50, 0.07) |

5.61 ± 5.64 |

2.48 ± 2.47 |

3.03 ± 3.60 |

-0.22

(-0.57, 0.14) |

2.33 ± 3.31 |

1.00 ± 1.71 |

1.33 ± 1.91 |

-0.22

(-0.69, 0.25) |

| HSRD (m) |

77.47 ± 100.91 |

33.84 ± 42.78 |

42.66 ±

65.21 |

-0.20

(0.48, 0.09) |

102.33± 113.62 |

44.52 ± 45.95 |

56.29 ± 76.10 |

-0.22

(-0.57, 0.14) |

34.63 ± 53.82 |

15.45 ± 29.59 |

19.18 ± 29.41 |

-0.16

(-0.62, 0.31) |

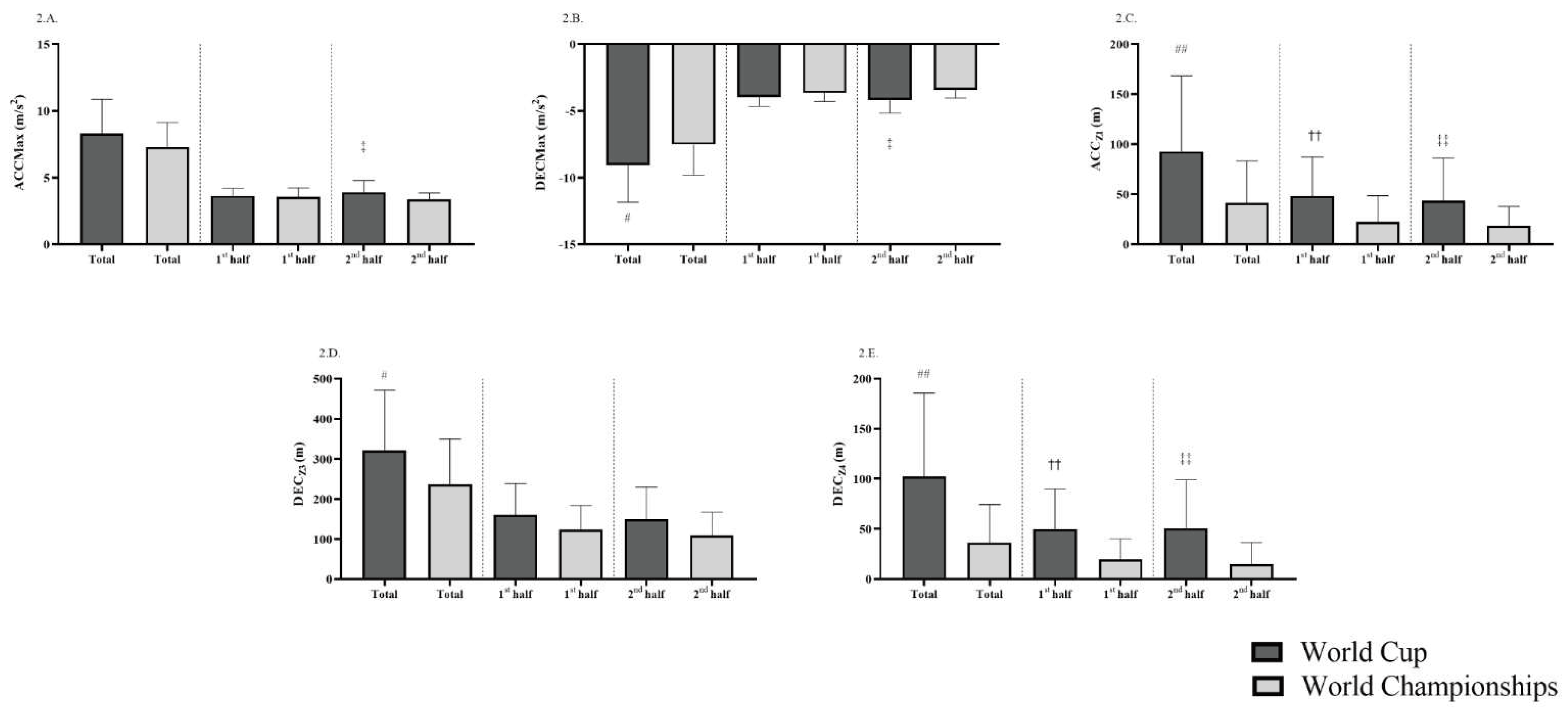

With respect to the comparison between the two tournaments and the short term-actions, a similar pattern was presented in which referees during the World Cup performed more ACCMax in the 2nd half (p = 0.03; d = 0.68; moderate), and more DECMax in the total time and 2nd half (p < 0.05; d = -0.60 to -0.85; moderate to large) (

Figure 2). Additionally, more distance covered for total time and both halves were described in World Cup referees when accelerating (p < 0.01; d = 0.70 to 0.78; moderate) and decelerating (p < 0.01; d = 0.87 to 0.94; large) at Z4 intensity and deceleration at Z3 (p = 0.04; d = 0.62; moderate) intensity only for the total time.

On the other hand, concerning the analysis between halves, referees in the World Cup tournament showed a higher number of accelerations (p = 0.01; d = -0.55; moderate) and decelerations (p < 0.01; d = -0.54; moderate) which were registered in the 2nd half compared to the 1st half (

Table 2). In addition, the distance accelerating at Z1 (p < 0.04; d = -0.38; small) was significantly greater in the 2nd half compared to the 1st half. For the World Championships the DECMax (p = 0.04; d = -0.52; moderate) and deceleration in Z2 (p = 0.03; d = -0.58; moderate) were significantly greater in the 1st half compared to the 2nd half.

Table 2.

Physical response variables by referees in cerebral palsy football match related to the number of accelerations, deceleration, maximal acceleration, maximal deceleration, distance covered accelerating and decelerating at different speeds, and player load in both halves of the World Cup and World Championships.

Table 2.

Physical response variables by referees in cerebral palsy football match related to the number of accelerations, deceleration, maximal acceleration, maximal deceleration, distance covered accelerating and decelerating at different speeds, and player load in both halves of the World Cup and World Championships.

| |

Total Sample (n = 13 referees, 49 observations) |

|

World Cup (n = 8 referees, 31 observations) |

World Championships (n = 7 referees, 18 observations) |

| Variables |

Total |

1st half |

2nd half |

d (95% CI) |

Total |

1st half |

2nd half |

d (95% CI) |

Total |

1st half |

2nd half |

d (95% CI) |

| Accelerations (n) |

1839.04 ± 281.66 |

870.18 ± 94.60 |

904.90 ± 113.65 |

-0.28

(-0.57, 0.01) |

1839.13 ± 265.64 |

852.81 ± 70.38 |

907.68 ± 93.41 |

-0.55

(-0.93, -0.17)** |

1838.89 ± 315.39 |

900.11 ± 122.59 |

900.11 ± 145.04 |

0.00

(-0.46, 0.46) |

| Decelerations (n) |

1848.64 ± 277.48 |

875.16 ± 94.32 |

909.22 ± 112.90 |

-0.27

(-0.56, 0.01) |

1848.23 ± 261.93 |

856.65 ± 69.09 |

912.32 ± 94.15 |

-0.54

(-0.91, -0.16)** |

1849.44 ± 310.38 |

907.06 ± 122.44 |

903.89 ± 142.47 |

0.02

(-0.44, 0.48) |

| ACCMax (m/s2) |

7.94 ± 2.34 |

3.61 ± 0.59 |

3.71 ± 0.79 |

-0.13

(-0.41, 0.15) |

8.33 ± 2.53 |

3.64 ± 0.54 |

3.90 ± 0.88 |

-0.30

(-0.66, 0.06) |

7.28 ± 1.84 |

3.56 ± 0.67 |

3.38 ± 0.47 |

0.38

(-0.10, 0.86) |

| DECMax (m/s2) |

-8.51 ± 2.68 |

-3.86 ± 0.68 |

-3.91 ± 0.94 |

0.06

(-0.22, 0.34) |

-9.08 ± 2.76 |

-3.98 ± 0.67 |

-4.18 ± 1.00 |

0.22

(-0.14, 0.58) |

-7.53 ± 2.28 |

-3.66 ± 0.65 |

-3.43 ± 0.60 |

-0.52

(-1.00, -0.02)* |

| Distance covered at different acceleration intensities |

| Z1 (m) |

1361.33 ± 266.37 |

646.38 ± 91.81 |

664.77 ± 119.32 |

-0.22

(-0.50, 0.07) |

1395.52 ± 256.10 |

650.85 ± 96.90 |

681.89 ± 104.17 |

-0.38

(-0.74, -0.01)* |

1302.46 ± 280.68 |

638.66 ± 84.44 |

635.29 ± 139.97 |

0.04

(-0.42, 0.50) |

| Z2 (m) |

1052.97 ± 268.45 |

509.46 ± 102.27 |

502.68 ± 120.62 |

0.08

(-0.20, 0.36) |

1091.34 ± 292.37 |

513.49 ± 110.09 |

522.74 ± 116.07 |

-0.12

(-0.48, 0.23) |

986.88 ± 212.87 |

502.51 ± 89.80 |

468.14 ± 123.74 |

0.35

(-0.14, 0.82) |

| Z3 (m) |

392.07 ± 171.52 |

194.15 ± 96.83 |

187.20 ± 87.16 |

0.10

(-0.18, 0.38 |

422.37 ± 194.37 |

206.21 ± 109.96 |

202.24 ± 97.19 |

0.06

(-0.30, 0.41) |

339.88 ± 108.81 |

173.38 ± 66.46 |

161.29 ± 60.48 |

0.17

(-0.30, 0.64) |

| Z4 (m) |

73.99 ± 69.34 |

38.79 ± 36.67 |

34.44 ± 37.53 |

0.17

(-0.12, 0.45) |

92.78 ± 75.61 |

48.19 ± 39.00 |

43.61 ± 42.55 |

0.15

(-0.20, 0.51) |

41.63 ± 41.66 |

22.61 ± 25.95 |

18.64 ± 19.09 |

0.22

(-0.25, 0.68) |

| Distance covered at different deceleration intensities |

| Z1 (m) |

1468.99 ± 253.22 |

697.37 ± 73.94 |

718.26 ± 114.96 |

0.23

(-0.51, 0.06) |

1470.22 ± 261.91 |

692.48 ± 74.97 |

710.01 ± 103.88 |

-0.21

(-0.56, 0.15) |

1466.89 ± 244.93 |

705.79 ± 73.49 |

732.46 ± 133.91 |

-0.26

(-0.72, 0.22) |

| Z2 (m) |

1025.72 ± 242.67 |

498.85 ± 93.21 |

488.73 ± 113.45 |

0.12

(-0.16, 0.40) |

1052.06 ± 279.31 |

490.97 ± 105.32 |

507.75 ± 114.94 |

-0.26

(-0.62, 0.10) |

980.34 ± 158.62 |

512.43 ± 68.18 |

455.97 ± 105.99 |

0.58

(0.07, 1.07)* |

| Z3 (m) |

290.19 ± 142.344 |

146.98 ± 73.70 |

134.40 ± 75.00 |

0.24

(-0.05, 0.52) |

321.27 ± 149.97 |

160.75 ± 77.89 |

149.50 ± 80.12 |

0.20

(-0.16, 0.56) |

236.65 ± 112.79 |

123.26 ± 60.73 |

108.38 ± 58.50 |

0.30

(-0.18, 0.77) |

| Z4 (m) |

78.19 ± 76.62 |

39.00 ± 36.82 |

37.49 ± 43.83 |

0.06

(-0.23, 0.34) |

102.38 ± 83.25 |

50.07 ± 39.84 |

50.56 ± 48.31 |

-0.02

(-0.37, 0.34) |

36.52 ± 37.98 |

19.94 ± 20.44 |

14.98 ± 21.41 |

0.26

(-0.22, 0.72) |

| PL (AU) |

60.13 ± 18.09 |

29.27 ± 7.51 |

28.62 ± 7.62 |

0.16

(-0.12, 0.44) |

59.86 ± 22.01 |

28.40 ± 8.62 |

28.36 ± 8.78 |

0.02

(-0.34, 0.37) |

60.59 ± 8.25 |

30.76 ± 4.95 |

29.06 ± 5.26 |

0.31

(-0.17, 0.78) |

4. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine the physical responses of field international referees of CP football during different matches according to the level of competition (World Cup or World Championship) and considering game time. Previous studies have sought to understand referees’ physical responses to non-impaired football based on elements of the level of competition, [

13], their position on the field, as a referee or an assistant referee [

13,

15,

24], contextual factors that may have been at play [

25], and a host of other situations that may have taken place in each of the halves of a game. To the best of the author’s knowledge, this is the first study to analyze the differences in physical responses between tournaments and halves in referees of CP football.

The results of this study showed that CP football referees covered a distance of 5731.82 ± 950.00 m of which 2591.58 ± 288.54 m was walking, 2066.24 ± 518.78 m was jogging, 905.62 ± 303.00 m was at medium intensity, 114.22 ± 74.64 m was at high intensity, 39.04 ± 48.28 m was sprinting, and 15.13 ± 34.61 m was at maximum sprinting. Previous studies on regular football referees officiating international matches showed that referees covered on average between 10.300 and 11.300 m [

26,

27], a significantly longer distance. However, the distances covered by amateur referees in regular football are considerably less, averaging between 8.650 and 9.990 m per match [

28,

29]. Notwithstanding, previous studies carried out with referees are in 11-a-side football, whose minimum dimensions are 45 x 90 m, while CP football is played on 7-a-side fields, whose dimensions are 50 x 70 m and the size of the field of play has already been shown to influence amateur refereeing, with the smallest fields of play being the ones where referees have registered the least physical responses [

30]. This may be one of the reasons for the differences found in the physical responses recorded by referees in football and CP football matches.

Competitive sports such as CP football require a considerable number of acceleration and deceleration actions generating higher mechanical and metabolic loads necessary to fulfill technical and tactical needs [

31]. In the present study, referees of CP football performed 1839.04 ± 261.66 accelerations and 1848.64 ± 277.48 decelerations per match. In contrast, previous studies in regular football have shown a higher number of accelerations and decelerations per game ~2813.02 and ~2813.16 [

32]. Taking into account that the duration of a regular football match is 90 min as compared to 60 min for the adapted modality, it is reasonable to suggest that the accelerations per minute performed by referees in CP football are similar to the accelerations performed by regular referees. It is clear that in the international game places demands on acceleration and deceleration actions highlighting that referees must be physically prepared to keep up with the game at any level of international play [

12]. Interestingly, the obtained results in maximum speed (22.04 ± 2.69 km/h) were similar to those described by regular football referees, registering ~20.86 km/h [

33], ~25.47 km/h [

34], and ~19.40 km/h [

35]. However, lower short-term actions were presented in CP football referees as compared to the performance of referees in regular football which might be due to the specific characteristics, the field size, and the demands of the para-sport. Further, PL has been indicated as a variable that involves the sum of the accelerations in different planes and is commonly used to understand demands in football. In this regard, no significant differences were found between tournaments and between halves, which may lead us to believe that the use of this metric could be useful with an individualized approach to understanding the referees load [

18].

Significant differences were present in physical response variables when the different tournaments were analyzed, demonstrating a pattern in which match physical demands of referees were higher in the tournament that involved teams of a higher ranking (i.e., World Cup). Previous studies on regular football referees have shown that in the higher-level categories, the physical responses of referees were similarly higher [

32,

36]. It is likely that contextual factors such as the level of competition can be a variable that influences the physical response, however with the particular analysis used, it is not possible to infer this causation. In regular football, it has been shown that the physical response of referees is largely based on the players’ performance metrics [

37,

38]. In this regard, Henríquez et al. [

11], explored the difference in the physical response of international footballers with CP, suggesting that players from top-ranked teams playing against teams of similar level reported higher physical demands, or when bottom-ranked teams played against teams of equivalent rank. In much that same way, the physical responses of the referees who officiated World Cup matches have been higher than the physical responses registered by the referees of the World Championships, given that in conventional football, it has also been observed that the players of higher competitive level register higher physical responses [

39,

40]. The fact that players belong to a higher competitive level implies that they are exposed to greater physical responses [

39,

40]. The present results suggest that referees must, at minimum, be prepared for the based level requirements demanded by the type of competition but ultimately should be prepared for the highest levels of demands that the competition can provide in order to meet the demand of the players there are officiating.

When analyzing differences between game halves, no differences were found in the total values of the variables in the present study. However, when analyzing the World Cup, significant differences were found in accelerations, decelerations, and Z1 (accelerations), with these being higher in the 2nd half. On the other hand, in the World Championships, referees covered a greater distance jogging in the 1st half. Additionally, differences were found in maximum deceleration variables and Z2 (decelerations), with these being higher in the first half of the match. While the findings have been mixed in the existing literature with respect to these variables, there have been some studies that demonstrated that physical responses were reduced in the 2nd half [

27,

41], as was the case for the World Championship in this study. More recent studies have shown that there were no differences in the distance covered between the 1st and 2nd halves, [

32,

33,

42,

43] which is consistent with what is reported in the total values of the observations in this study. The negative influence of eligible impairments in footballers with CP have been extensively studied showing diminished physical performance as compared to footballers without CP [

2,

9,

44,

45]. It would make sense then that the demands of the referees would mirror the demands of the game and the athletes within the game for both 11v11 and 7v7 CP football games. While this analysis was not done in this study, an additional research could be undertaken to explore the distinctions between the first and second halves within the same tournament and a comparison between the demands of the CP Football referee and the regular 11v11 referee as compared to the demands of the players in each of the two distinct versions of the game.

5. Conclusions

This study has described the physical responses that referees of CP football endure during international tournaments thus providing new information for physical trainers to adjust weekly-monthly training loads. The results of the present study show International, top-level tournaments have demonstrated to require greater physically responses from referees who officiated CP football matches than lower-level tournaments, in terms of covering more total distance, more explosive distance, and greater distances covered at various intensities during the first and second halves. Therefore, the results suggest that the physical responses of officiating top-level CP football matches are higher than officiating lower-level matches. Similarly, there were small differences noted between the two halves of the match in that there are more accelerations and decelerations in the second halves of matches, although only a moderate effect size was noted.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.H., M.C., S.A. and J.Y.; methodology, E.O., D.C., A.I. and R.R.; software, M.H., E.O., D.C. and J.Y.; validation, R.R., M.C., A.I. and S.A.; formal analysis, R.R. and S.A.; investigation, M.H. and E.O.; resources, A.I. and M.C.; data curation, D.C. and J.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, M.H., E.O., D.C. and J.Y.; writing—review and editing, M.H., E.O., R.R., D.C., M.C., A.I., S.A. and J.Y.; visualization, M.H., E.O., R.R. and D.C.; supervision, M.C., A.I., S.A. and J.Y.; project administration, R.R. and J.Y..; funding acquisition, A.I.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Miguel Hernández University (DPS.RRV.03.17).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the referees who participated in this study and the International Federation of Cerebral Palsy Football for all the support to do this investigation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Graham, H.K.; Rosenbaum, P.; Paneth, N.; Dan, B.; Lin, J.-P.; Damiano, Di.L.; Becher, J.G.; Gaebler-Spira, D.; Colver, A.; Reddihough, D.S.; et al. Cerebral Palsy. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2016, 2, 15082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henríquez, M.; Peña-González, I.; Albaladejo-García, C.; Sadarangani, K.P.; Reina, R. Sex Differences in Change of Direction Deficit and Asymmetries in Footballers with Cerebral Palsy. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reina, R. Evidence-Based Classification in Paralympic Sport: Application to Football -7-a-Side. European Journal of Human Movement 2014, 32, 161–185. [Google Scholar]

- Reina, R.; Iturricastillo, A.; Castillo, D.; Urbán, T.; Yanci, J. Activity Limitation and Match Load in Para-Footballers with Cerebral Palsy: An Approach for Evidence-Based Classification. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2020, 30, 496–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanci, J.; Castillo, D.; Iturricastillo, A.; Urbán, T.; Reina, R. External Match Loads of Footballers with Cerebral Palsy: A Comparison among Sport Classes. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 2018, 13, 590–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, A.M.; Ma’ayah, F.; Harms, C.A.; Newton, R.U.; Drinkwater, E.J. Global Positioning System Activity Profile in Male Para Footballers with Cerebral Palsy. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2021, Publish Ah. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-González, I.; Sarabia, J.M.; Roldan, A.; Manresa, A.; Moya-Ramón, M. Physical Performance Differences between Spanish Selected and Non-Selected Para-Footballers with Cerebral Palsy for the National Team. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 2021, Ahead of p. [Google Scholar]

- Peña-González, I.; Maggiolo, J.F.; Javaloyes, A.; Moya-Ramón, M. Analysis of Scored Goals in the Cerebral Palsy Football World Cup. J Sports Sci 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanci, J.; Castillo, D.; Iturricastillo, A.; Reina, R. Evaluation of the Official Match External Load in Soccer Players with Cerebral Palsy. J Strength Cond Res 2019, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weston, M.; Castagna, C.; Impellizzeri, F.M.; Bizzini, M.; Williams, A.M.; Gregson, W. Science and Medicine Applied to Soccer Refereeing. Sports Medicine 2012, 42, 615–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henríquez, M.; Reina, R.; Castillo, D.; Iturricastillo, A.; Yanci, J. Contextual Factors and Match-Physical Performance of International-Level Footballers with Cerebral Palsy. Science and Medicine in Football 2023, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castagna, C.; Abt, G.; Dottavio, S. Physiological Aspects of Soccer Refereeing Performance and Training. Sports Medicine 2007, 37, 625–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbero-Álvarez, JoséC. ; Boullosa, D.A.; Nakamura, F.Y.; Andrín, G.; Castagna, C. Physical and Physiological Demands of Field and Assistant Soccer Referees During America’s Cup. J Strength Cond Res 2012, 26, 1383–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, D.; Cámara, J.; Lozano, D.; Berzosa, C.; Yanci, J. The Association between Physical Performance and Match-Play Activities of Field and Assistants Soccer Referees. Research in Sports Medicine 2019, 27, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krustrup, P.; Helsen, W.; Randers, M.B.; Christensen, J.F.; MacDonald, C.; Rebelo, A.N.; Bangsbo, J. Activity Profile and Physical Demands of Football Referees and Assistant Referees in International Games. J Sports Sci 2009, 27, 1167–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IFCPF Classification Rules and Regulations. International Federation of CP Football 2018, 1–113.

- Bastida Castillo, A.; Gómez Carmona, C.D.; De la cruz sánchez, E.; Pino Ortega, J. Accuracy, Intra- and Inter-Unit Reliability, and Comparison between GPS and UWB-Based Position-Tracking Systems Used for Time–Motion Analyses in Soccer. Eur J Sport Sci 2018, 18, 450–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reche-Soto, P.; Cardona-Nieto, D.; Diaz-Suarez, A.; Bastida-Castillo, A.; Gomez-Carmona, C.; Garcia-Rubio, J.; Pino-Ortega, J. Player Load and Metabolic Power Dynamics as Load Quantifiers in Soccer. J Hum Kinet 2019, 69, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamonales, J.M.; Muñoz-Jiménez, J.; Gómez-Carmona, C.D.; Ibáñez, S.J. Comparative External Workload Analysis Based on the New Functional Classification in Cerebral Palsy Football 7-a-Side. A Full-Season Study. Research in Sports Medicine 2021, 00, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin-Sanchez, M.L.; Oliva-Lozano, J.M.; Garcia-Unanue, J.; Felipe, J.L.; Moreno-Pérez, V.; Gallardo, L.; Sánchez-Sánchez, J. Physical Demands in Spanish Male and Female Elite Football Referees during the Competition: A Prospective Observational Study. Science and Medicine in Football 2022, 6, 566–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mara, J.K.; Thompson, K.G.; Pumpa, K.L.; Morgan, S. Quantifying the High-Speed Running and Sprinting Profiles of Elite Female Soccer Players During Competitive Matches Using an Optical Player Tracking System. J Strength Cond Res 2017, 31, 1500–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva-Lozano, J.M.; Rojas-Valverde, D.; Gómez-Carmona, C.D.; Fortes, V.; Pino-Ortega, J. Impact of Contextual Variables on the Representative External Load Profile of Spanish Professional Soccer Match-Play: A Full Season Study. Eur J Sport Sci 2021, 21, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; L. Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, N.J., 1988; ISBN 9780805802832 0805802835. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo, D.; Yanci, J.; Cámara, J.; Weston, M. The Influence of Soccer Match Play on Physiological and Physical Performance Measures in Soccer Referees and Assistant Referees. J Sports Sci 2016, 34, 557–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozaeta, E.; Yanci, J.; Raya-González, J.; Fernández, U.; Castillo, D. The Influence of Contextual Variables on Physical and Physiological Match Demands in Soccer Referees. Archivos de Medicina del Deporte 2022, 39, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krustrup, P.; Helsen, W.; Randers, M.B.; Christensen, J.F.; Macdonald, C.; Rebelo, A.N.; Bangsbo, J. Activity Profile and Physical Demands of Football Referees and Assistant Referees in International Games. J Sports Sci 2009, 27, 1167–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Salvo, V.; Carmont, M.R.; Maffulli, N. Football Officials Activities during Matches: A Comparison of Activity of Referees and Linesmen in European, Premiership and Championship Matches. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J 2011, 1, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Castillo, D.; Weston, M.; McLaren, S.J.; Cámara, J.; Yanci, J. Relationships between Internal and External Match-Load Indicators in Soccer Match Officials. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 2017, 12, 922–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozaeta, E.; Yanci, J.; Castagna, C.; Romaratezabala, E.; Castillo, D. Associations between Well-Being State and Match External and Internal Load in Amateur Referees. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozaeta, E.; Yanci, J.; Raya-Gonzalez, J.; Fernandez, U.; Castillo, D. The Influence of Contextual Variables on Physical and Physiological Match Demands in Soccer Referees. Archivos de medicina del Deporte 2022, 39, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, D.J.; Carling, C.; Kiely, J. High-Intensity Acceleration and Deceleration Demands in Elite Team Sports Competitive Match Play: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Sports Medicine 2019, 49, 1923–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Torremocha, G.; Martin-Sanchez, M.L.; Garcia-Unanue, J.; Felipe, J.L.; Moreno-Pérez, V.; Paredes-Hernández, V.; Gallardo, L.; Sanchez-Sanchez, J. Physical Demands on Professional Spanish Football Referees during Matches. Science and Medicine in Football 2023, 7, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozaeta, E.; Fernandez, U.; Martinez-Aldama, I.; Cayero, R.; Castillo, D. Match Physical and Physiological Response of Amateur Soccer Referees: A Comparison between Halves and Match Periods. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, D.; Cámara, J.; Castellano, J.; Yanci, J. Football Match Officials Do Not Attain Maximal Sprinting Speed during Matches. Kinesiology 2016, 48, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, E.C.; Vieira, C.M.A.; Moreira, A.; Ugrinowitsch, C.; Castagna, C.; Aoki, M.S. Monitoring External and Internal Loads of Brazilian Soccer Referees during Official Matches. J Sports Sci Med 2013, 12, 559–564. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fernandes da Silva, J.; Teixeira, A.S.; de Carvalho, J.; Do Nascimento Salvador, P.; Castagna, C.; Ventura, A.P.; Segundo, J.F. de S.N.; Guglielmo, L.G.A.; de Lucas, R.D. Match Activity Profile and Heart Rate Responses of Top-Level Soccer Referees during Brazilian National First and Second Division and Regional Championships. Science and Medicine in Football 2022, 7, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weston, M.; Drust, B.; Gregson, W. Intensities of Exercise during Match-Play in FA Premier League Referees and Players. J Sports Sci 2011, 29, 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillo, D.; Cámara, J.; Yanci, J. Comparative Analysis of the Physical Response of a Soccer Referee and a Midfielder during a Soccer Match. Revista Internacional de Deportes Colectivos 2017, 29, 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, L.D.A.; Brito, M.A.; Muñoz, P.M.; Pérez, D.I.V.; Kohler, H.C.; Aedo-Muñoz, E.A.; Slimani, M.; Brito, C.J.; Bragazzi, N.L.; Znazen, H.; et al. Match Running Performance of Brazilian Professional Soccer Players According to Tournament Types. Montenegrin Journal of Sports Science and Medicine 2022, 11, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccardo Izzo; Angelo De Vanna; Ciro Hosseini Varde’i Data Comparison between Elite and Amateur Soccer Players by 20 Hz GPS Data Collection. Journal of Sports Science 2018, 6. [CrossRef]

- Catterall, C.; Reilly, T.; Atkinson, G.; Coldwells, A. Analysis of the Work Rates and Heart Rates of Association Football Referees. Br J Sports Med 1993, 27, 193–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, D.; Cámara, J.; Yanci, J. Análisis de Las Respuestas Físicas y Fisiológicas de Árbitros y Asistentes de Fútbol Durante Partidos Oficiales. RICYDE: Revista Internacional de Ciencias del Deporte 2016, 45, 250–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbero-Álvarez, J.C.; Boullosa, D.A.; Nakamura, F.Y.; Andrín, G.; Castagna, C. Physical and Physiological Demands of Field and Assistant Soccer Referees during Americaʼs Cup. J Strength Cond Res 2012, 26, 1383–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanci, J.; Castagna, C.; Los Arcos, A.; Santalla, A.; Grande, I.; Figueroa, J.; Camara, J. Muscle Strength and Anaerobic Performance in Football Players with Cerebral Palsy. Disabil Health J 2016, 9, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reina, R.; Iturricastillo, A.; Sabido, R.; Campayo-Piernas, M.; Yanci, J. Vertical and Horizontal Jump Capacity in International Cerebral Palsy Football Players. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 2018, 13, 597–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).