1. Introduction

Brand love is the most emotionally intense consumer–brand relationship. Loved brands exert many strong, positive effects on consumers´ behaviours, including greater brand loyalty, willingness to pay more, positive word of mouth and resistance to negative information [

1,

2,

3]. The brand love concept interests academics and industry professionals [

3]. They place a high value on brand love because delighted customers who become loyal customers reduce costs and support marketing activity [

4]. Some authors have argued that brand love is similar to the feelings that develop between humans [

2].

Brand love is a reflection of the emotional responses of satisfied consumers. This ‘love-like’ attachment stems from a deep satisfaction with the brand. Researchers have argued that positive emotions play a strong role in brand love [

5]. Positive emotions are associated with consumers’ willingness to invest time, effort and resources into the brands they love [

1]. Customer happiness has been described as a very high level of enjoyment in the customer experience, which influences overall satisfaction [

6]. In the highly competitive automobile business environment, every car dealer tries hard to make their customers happy. There is evidence in the previous literature that the customer´s happiness with service facilities is the key to increasing his/her brand love [

6]. Many factors affect customer happiness. For businesses to be successful in the long term in this competitive environment they must identify these factors and gauge their relative importance based on their customers’ needs [

7]. In previous studies researchers have paid little attention to identifying the drivers of customers´ happiness with car dealerships. This study addresses this research gap.

Over the last 20 years, as the global economy has become more service-oriented, researchers now consider services as the central orientation of marketing. Superior customer perceived service quality can enhance customers´ perceptions of the benefits they derive from a car dealership and reduce their mental stress and other, non-monetary, costs [

8]. [

9] demonstrated that consumers are impacted by customer perceived service quality more in the automobile industry than in other industries. In the present study it is proposed that perceived service quality (PSQ) is one of the most determinant factors of customer trust and positive emotions.

Although brand love is acknowledged as being an important construct in consumer–brand relationships [

1], only limited research has taken place into the combined influence of the cognitive and affective drivers of brand love, and its consequences for these relationships. Offering automobile customers high-quality services, based on their needs and expectations, is increasingly seen as a condition for developing successful marketing strategies that satisfy and retain customers. The novelty of the present study lies in its exploration of the links between the dimensions of perceived service quality, customer happiness, brand love and its effects on behavioural intentions (willingness to pay more, positive word-of-mouth and resistance to negative information posted on social media,).

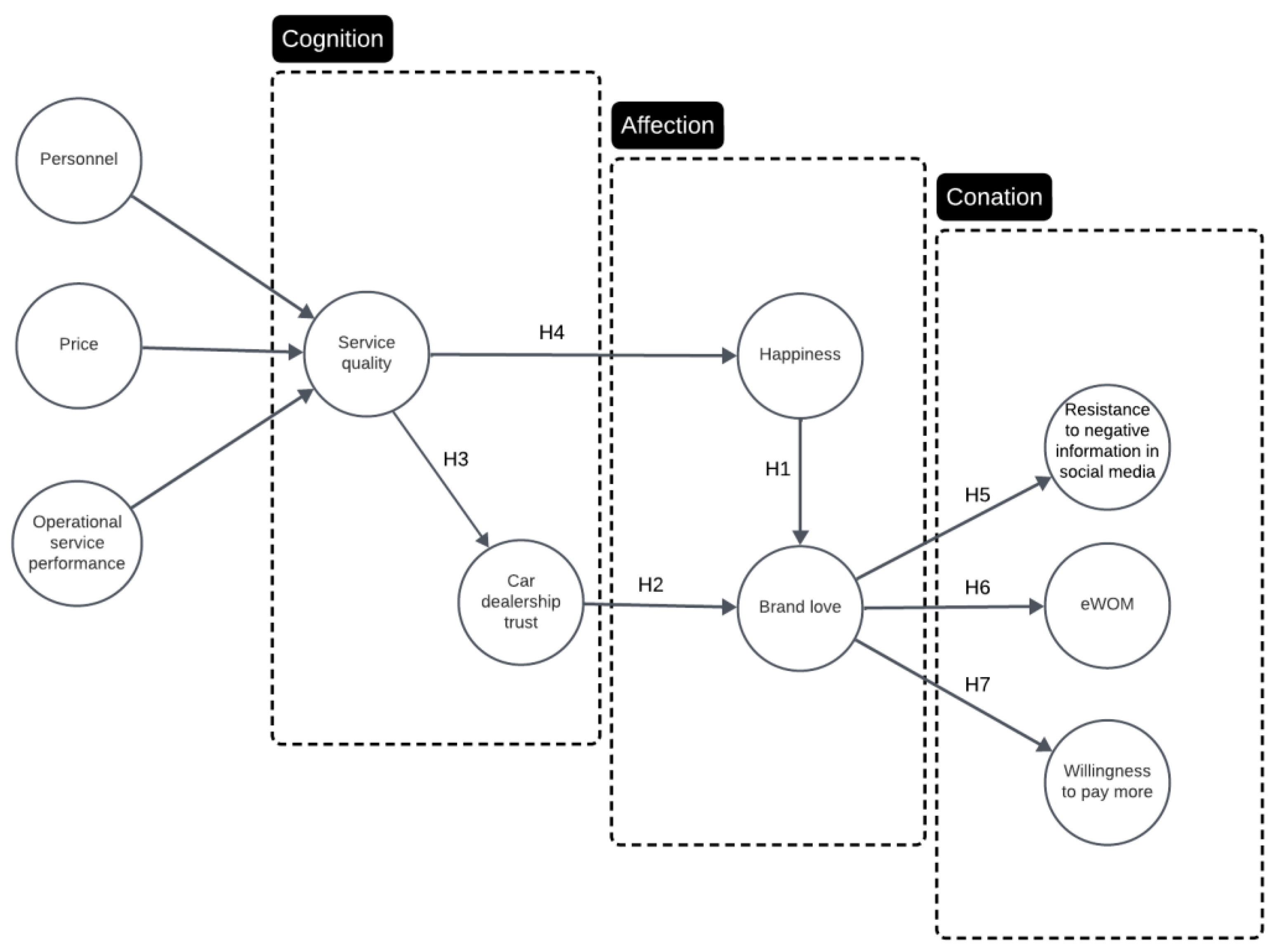

This study makes three contributions to the literature. First, to explain brand love, we follow the cognition, affection, conation sequence, which has been widely used to explain diverse consumer behaviours. To be precise, we examine: the consumer’s beliefs about the perceived service quality of the dealership; their trust in the dealership; and customer happiness. Second, we expand the knowledge of the effects of brand love on customer behaviours. Specifically, the study focuses on three crucial behavioural intentions, willingness to pay more, positive electronic word of mouth and customers’ resistance to negative information posted on social media. Given the increasing competition in the automobile industry, it is important to understand the drivers of customer happiness and brand love, as these variables have considerable influence on customers´ behavioural decision-making processes [

3].

2. Literature review and hypotheses development

The cognition-affection-conation (C-A-C) framework [

10] is based on the sequential linkages of cognition-affection and conation in human decision-making processes: cognitive factors lead to affective outcomes that consequently impact on conation, which ultimately stimulates actual behaviours. Cognition relates to a person's thoughts, beliefs and values regarding an object; affect relates to a person's feelings or emotions felt towards the object; and conation represents the development of the individual´s behavioural intentions and actual behaviours towards that object. The C-A-C framework has been widely used to examine human behaviours in various contexts, including information systems [

11]. The framework illustrates how consumers translate their experiences, learning and perceptions into behaviours through affect, which is precisely in line with our objective of understanding the behaviours of car brand loving clients.

2.1. Affective factors: positive emotions and brand love

[

2] argued that brand love is the satisfied consumer’s deep emotional relationship with a specific brand. These authors suggested that brand love has five distinctive characteristics: passion for the brand, connection with the brand, positive evaluation of the brand, positive emotions towards the brand and (explicit) declarations of love for the brand. Brand love is a customer’s passionate emotional attachment for a brand, which is characterised by passion, intimacy and decision/commitment [

2]. Passion is the enthusiasm that stems from the consumer’s motivational involvement with the brand; intimacy is his/her emotional willingness to remain connected to the brand and decision/commitment relates to his/her short-and long-term decisions to love and commit to the brand.

Brand love is based on emotions, such as happiness, and has been described as being an integral part of the use of a product or service [

6]. Brand love has been said to pertain to affection, and is the product of prolonged purchase interactions [

12]. Previous research [

5] has shown that consumer happiness is a crucial prerequisite for brand love. Based on this previous research, we argue that consumers who feel happy about their car purchasing experience at a car dealership will be more likely to develop brand love towards the car brand purchased. Hence, we propose that:

Hypothesis 1 (H1). Happiness evoked by the car purchasing experience at the dealership increases brand love for the car brand.

2.2. Cognitive factors

2.2.1. Beliefs about the car dealership and social influences

In the field of relationship marketing there is general agreement that trust is the belief held by one party (the consumer) in the integrity and good faith of the other party in the exchange (the company) [

13]. The trust that consumers feel towards their favourite car dealership is based on whether they perceive it to be trustworthy, successful and honest. [

14] argued that when consumers trust brands they develop emotional attachments to it, and that brand affect arises due to the trust they hold in the brand. [

15] demonstrated the mediating effect of automobile brand affect on the influence of brand trust on consumers’ resistance to negative information. Therefore, we argue that brand love stems from brand trust.

Hypothesis 2 (H2). Trust in the car dealership influences car brand love.

Perceived service quality has been described as the consumer´s judgment of the overall excellence or superiority of the service, measured usually by comparing expectations against perceived performance [

16]. Although there is no complete consensus on the most appropriate way to evaluate perceived service quality, SERVQUAL is unquestionably the most popular framework used [

17]. This measurement instrument is made up of five perceived service quality dimensions: tangibility (physical layout); reliability (providing error-free service); assurance (employees are technically competent); empathy (employees have the ability to adapt themselves); and responsiveness (employees are willing to help) [

16].

The trust that a consumer has in his/her car dealer can be based on cognition and/or affect [

18]. That is, the consumer can develop trust based on his/her perceptions of the competence, credibility and reliability of the car dealer (cognitive-based trust) and, on the other hand, based on the friendliness, pleasantness and likability (affect-based trust) of the dealer. In the automobile industry, customers remain in regular contact with workshops for their repair and maintenance needs, and we argue that perceived service quality helps customers develop trust. [

6] identified perceived service quality as a driver of customer happiness. Thus, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 3 (H3). The perceived service quality provided by the car dealership influences the customer´s trust in the car dealership.

Hypothesis 4 (H4). The perceived service quality provided by the car dealership evokes customer happiness.

2.3. Conative factors: effects of brand love on behavioural intentions

2.3.1. Brand love and resistance to negative information posted in social media.

There is evidence that brand loyalty can affect consumers´ resistance to negative social media content. [

15] argued that customers with a strong emotional attachment to a brand were more resistant to unfavourable information about the brand. Similarly, [

19] found that customers with a strong emotional connection to a business were less likely to be affected by negative information about it posted on social media, than were customers without this connection. Thus, customers with a high level of brand love are more likely to adopt a positive frame of reference when processing negative information about brands [

20].

Based on the previous literature, we posit that brand love can increase customers' resistance to negative social media posts. Thus, we posit that consumers with a strong emotional connection to a car brand are more likely to maintain positive attitudes and beliefs about the brand, which can act as a barrier against negative reviews/comments posted on social media about the car brand.

Hypothesis 5 (H5) Brand love influences resistance to negative information posted on social media.

2.3.2. Brand love and positive eWOM

Several studies have shown that brand love significantly increases positive e-WOM. For example, [

1] found that consumers with a strong emotional connection to a brand are likelier, because they want to share their positive experiences with others, to engage in positive e-WOM. Similarly, [

2] found that brand love leads consumers to engage in more positive e-WOM, particularly when the brands are consistent with their self-identities. A loved brand is a vital component of a customer's self-expression, and by demonstrating affection for a particular brand, the consumer communicates his/her feelings about the brand. [

21] findings showed that positive associations between brand loyalty and eWOM exist. Therefore, we posit;

Hypothesis 6 (H6). Brand love influences consumers to engage in positive eWOM.

2.3.3. Brand love and willingness to pay more.

Willingness to pay a premium price is, according to [

22], "the highest price level at which the consumer is willing to pay for the goods or services". [

1] found that consumers with a deep emotional connection to a brand were willing to pay a premium for its products even when those offered by competitors were functionally comparable. Similarly, [

2] found that consumers with a strong emotional commitment to a brand were likelier to pay more for their products than were those without such an attachment. [

23] found that consumers with a deep emotional attachment to a brand were willing to spend up to 30% more on the company's items than were those without such a connection. Consumers who are deeply emotionally attached to a brand feel that it is irreplaceable; thus, they are willing to pay more for the brand [

24]. Consequently, we posit,

Hypothesis 7 (H7). Brand love influences willingness to pay more.

Figure 1.

Research model.

Figure 1.

Research model.

3. Methodology

The empirical study took place March-October 2023, in collaboration with The Leading Vehicles Company (Abu Khader Automotive), the leading automobile dealership in Jordan. Automobile dealerships merit investigation because automobiles have strong consumer involvement and great economic importance. In addition, the automobile industry is highly competitive, and brand love is a vital part of its marketing efforts [

25]. Jordan is one of the most rapidly expanding automobile markets in the region [

26]. The country's automotive industry is bolstered by several factors, including the availability of skilled labour, research and development initiatives, government backing and geographical advantages. With a favourable economic forecast and increased household purchasing power, the nation is poised to experience a substantial swell in automobile sales by the year 2030.

The present study follows a mixed methods research approach [

27]. Mixed methods offer a better understanding of research problems by triangulating two sets of results, thus enhancing the validity of findings. Accordingly, a two-step study was implemented. First, to adapt the SERVQUAL scale dimensions to the context of the research, we conducted, using a concept mapping methodology, a qualitative pre-test of the scale´s five dimensions. Second, we carried out a quantitative study to test the hypotheses of the proposed research model.

3.1. Qualitative pre-test: concept mapping analysis

Concept mapping is a group-based procedure in which a sequence of structured group activities is linked to a series of multivariate statistical analyses [

28]. A sample of eight Abu Khader staff was used in the research. The participants work in various departments involved in the customer journey (showroom, service centre, sales, CRM and marketing). [

29] recommended that groups used in these techniques should range from 8 to 15 participants. Specifically, ideas/concepts provided by participants are represented in the form of a perceptual map (using multivariate analysis techniques, Multidimensional Scaling Analysis and Cluster Analysis). The final output is a graphical representation of the participants’ beliefs, which depicts how these beliefs relate to each other and shows which are the most important in terms of customers´ evaluations of their service-based experiences.

The group meeting began with an explanation of the goals of the study and the methodology to be used. Brainstorming was then used to identify and weigh the participants’ beliefs about the perceived service quality provided by Abu Khader to its customers. The participants were then asked to write down, on an individual basis, within 30 minutes, statements that best reflected their own beliefs about how Abu Khader could make its customers perceive they receive excellent service quality during the purchase process. Next, they were asked to share, orally, on an individual and random basis, their views, so that the entire group could fully understand all the written statements provided. In this phase, repeated statements were deleted, that is, the participants were asked to delete statements if they were the same as statements provided previously by other participants. As a result, 21 statements were deleted. In this phase, also, steps were taken to remove any ambiguity in the statements and to agree on their meanings.

The study researchers created a deck of cards for each participant (while the participants had a coffee break), each card containing one statement. The participants were asked to weigh the importance of each statement, based on their experiences, on a scale of 0 to 10 (0 = Not at all important, 10 = Very important). Next, the participants individually grouped the statements using a similarity criterion (specific to each individual), that is, similar statements were placed within the same group. Each individual grouped the statements individually, on the basis of two criteria; 1) there had to be less groups than there were cards (statements) and 2) all statements could not be placed into one group. After the group meeting, the researchers created a similarity matrix for each of the participants. Finally, the researchers proposed a name for each cluster of beliefs, consistent with their content. On the basis of these activities, a conceptual map was developed, in which each belief was weighted according to the importance attributed to it by the participants in the first session. In addition, each cluster was assigned an importance weighting.

Concept mapping involved a second group meeting in which participants gave their opinions about the composition of the clusters, the group names and their assessment of the final list of beliefs about perceived service quality. In this second meeting, the participants were asked collectively about their views of the phenomenon under study and to combine their individually expressed beliefs (collected in first meeting). In this subjective process the participants collectively proposed amendments to both the number of clusters and their composition. The researchers accepted these changes given that the concept mapping technique involves an inductive approach; thus, the final results clearly reflect the participants’ beliefs.

The cluster map was subjected to the participants’ evaluation and interpretation during the second working session. The conclusion was that a reasonable number of clusters was in the range of three–five, with three groups being the optimal solution. Therefore, from this point on, the clusters were depicted on a map in which the perceived service quality statements were grouped in 3 clusters, that is, “personnel” (cluster 1), “price” (cluster 2), “operational service performance” which includes responsiveness-convenience-reliability dimensions (cluster 3).

3.2. Quantitative study

The quantitative study was based on data obtained from an online questionnaire. Questionnaires were distributed to a sample of 1,300 buyers who purchased Cadillacs, GMCs, Chevrolets or Opels from Abu Khader in the years 2020-2022.

While data gathered based on a single case has limitations in terms of the generalisation of results, this approach allowed us to conduct a very detailed analysis [

30]. We followed recent brand research studies that used a single case as a research context: [

31] measured active and passive participation in the Zara brand Facebook community; [

30] used a themed attraction restaurant to analyse experience value creation; [

32] used a Veepee company to analyse eWOM behaviours on the branded mobile apps of fashion retailers; [

33] used an eco-friendly restaurant to identify the effects of brand engagement on customer advocacy and behavioural intentions. We used online surveys [

34]. The customers were sent a URL that they could visit over a one-month period. The questionnaire was developed in English, and then translated into Arabic. We obtained 602 valid responses.

We operationalised the study constructs using multi-item scales measured mostly by five-point Likert scales, ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ (1) to ‘strongly agree’ (5). Happiness was measured on a single-item scale that asked respondents how happy they felt after their purchasing experience at the car dealer adapted from [

35]. Car brand love was measured using a 10-item scale adapted from [

2]. The respondents´ self-reported trust was measured using a 3-item scale adapted from [

36]. Willingness to pay more was measured using a 3-item scale adapted from [

25]. Intention to spread positive eWOM was measured using a 2-item scale adapted from [

37]. Resistance to negative information was measured using a 3-item scale adapted from [

38]. Finally, perceived service quality (PSQ) was measured as a formative second-order construct. We used the three dimensions identified in the concept mapping analysis to capture PSQ, that is “personnel”, “price” and “operational service performance”. The specific items to measure the dimensions were adapted from [

17]. The constructs and scales are shown at

Table 1.

4. Results

4.1. Psychometric properties of the measurement model

We established the theoretical structure of the model using the "repeated indicator approach" [

39] and partial least squares (PLS). We opted for PLS-SEM as the estimation method due to the complexity of the model, which involves numerous constructs (including a second-order formative construct), indicators and model relationships [

40]. The parameter estimation was carried out using Smart-PLS 4.0 [

41], and we performed bootstrapping with 5,000 samples to determine the significance of the parameters (see

Table 2). The composite reliability of the constructs exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.60 [

42]. In addition, the average variance extracted (AVE) for all constructs surpassed the 0.50 threshold [

43]. As an indicator of convergent validity, the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) demonstrated that all items were significantly related (p < 0.01) to their respective factors [

44].

Table 2 displays also the mean factor loadings for all the dimensions, each of which exceeds the criteria for convergent validity. Finally, the results show that the model has no collinearity problems in the reflective-formative second-order construct of perceived service quality.

The measurement model's ability to discriminate between constructs was verified using the [

43], the square roots of the AVEs exceeding the inter-construct correlations (see

Table 3, values below the diagonal). In addition, the heterotrait-monotrait ratio values (

Table 3, above the diagonal) support the conclusion that the measurement model possesses discriminant validity.

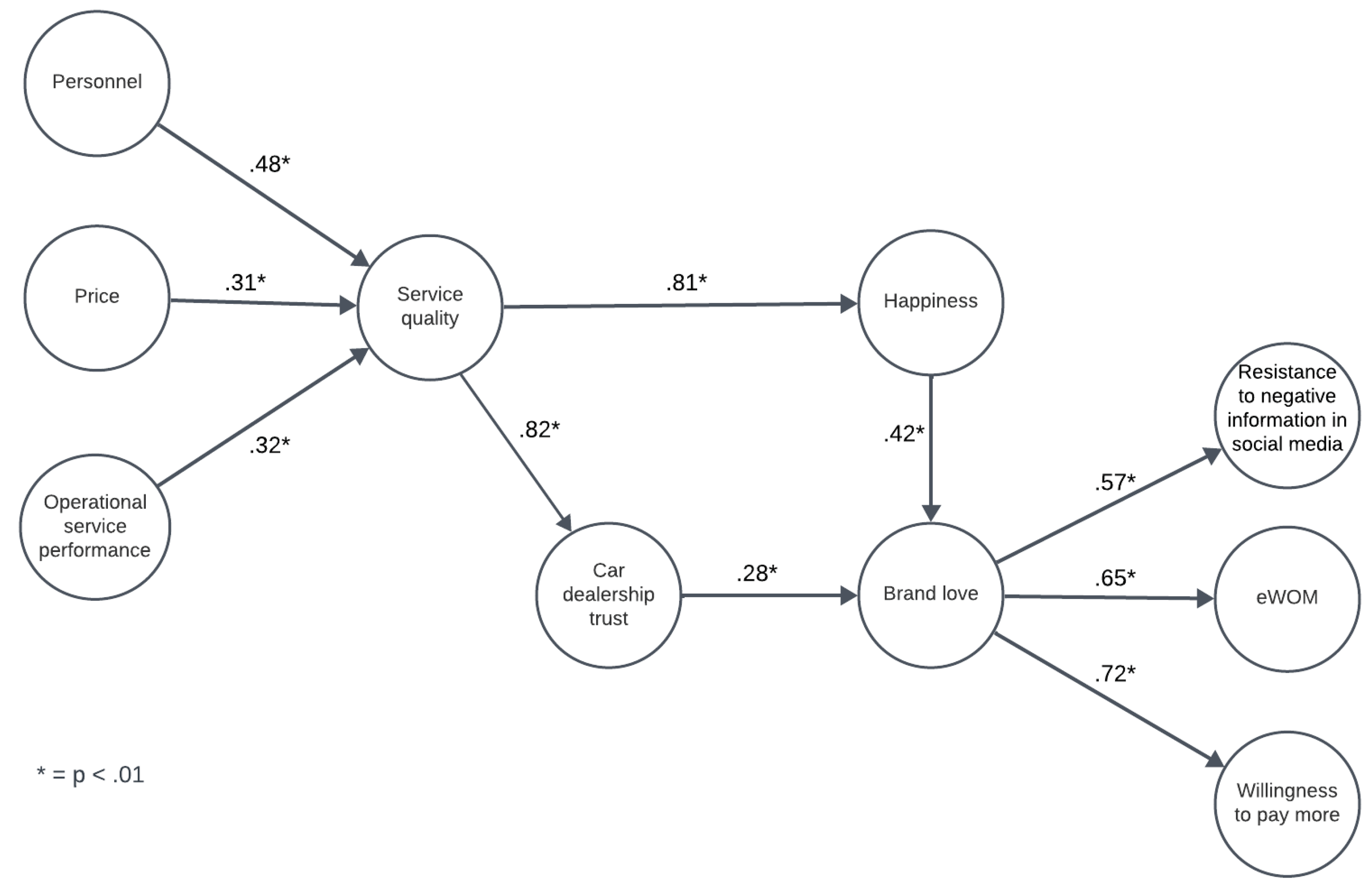

Table 4 presents the outcomes of the hypotheses testing and displays the standardised coefficients for each structural relationship and the corresponding significance levels of the t statistics.

Figure 2 provides a visual representation of the model's estimation

The results show that all the structural paths achieved bootstrap t values over 2.326, at a significance level of 1%, that is, 99% confidence. The estimation of the model confirms that PSQ is a powerful predictor of trust in the car dealership (β=.82, H3 accepted) and the happiness experienced by the customer (β=.82, H4 accepted), and that these two emotional responses towards the car dealership translate into greater car brand love for the manufacturer (happiness: β=.42, H1 accepted; trust: β=.81, H2 accepted). Finally, it was shown that car brand love is a significant driver of the three behavioural responses analysed: it generates resistance towards negative information on social networks (β=.57: H5 accepted), positive eWOM (β=.65: H6 accepted) and greater willingness to pay more (β=. 72: H7 accepted). This satisfactory estimation was accompanied by R2 and Q2 values that met the minimum established criteria; thus, the structural model shows predictive relevance

5. Conclusions

5.1. Discussion and theoretical implications

This research contributes to the existing literature on brand love and emotions and has implications for the automobile industry. The recent literature on emotions explains their importance in enhancing brand love. Understanding how perceived service quality generates brand love and how it relates to willingness to pay more, positive eWOM and resistance to negative information will help automobile retailers gain competitive advantage and respond to consumers’ demands.

This research extends the cognition-affection-conation framework [

10] by analysing the cognitive and emotional drivers of brand love derived from consumption experiences in the automobile industry. Combining consumers´ perceptions of perceived service quality and trust, and their happiness, provides insights that can help retailers create an optimal experience.

The previous literature shows that a direct relationship exists between company performance and customer happiness [

6]. However, few studies have examined sustaining customer happiness and improving customer retention after the actual purchase process. The present study reveals that perceived service quality plays a pivotal role in shaping customers' perceptions of car dealerships and their happiness after purchase.

The perceived service quality dimension “social interaction with personnel” was shown to have the highest influence on customer trust and happiness. This result supports previous research that showed that personalised attention [

45,

46,

47] and the behaviours of company personnel [

6,

48,

49] are important antecedents of the creation of positive emotions felt towards retailers. The perceived service quality dimension “price” also plays a vital role in customer happiness and trust, which shows that customers are conscious of cost effectiveness and price fairness. When customers feel that a car dealership is charging too much for its cars, repairs or spare parts they feel unhappy. Service providers should seek to retain a long-term customer base by providing value for money; this improves customer happiness with, and trust in, the car dealership. The perceived service quality dimension “operational service performance” has three sub-dimensions, convenience, reliability and responsiveness, all of which significantly influence customers´ beliefs. The customer´s service experience depends on the time it takes the dealership to complete the service provided [

50], on whether the provider performs as promised [

46,

49,

51,

52] and on the convenience of the service [

6,

48,

49].

The positive effect of perceived service quality on trust shows that the consumers used their perceived service quality perceptions to form their views about the dealership. Consumers´ perceived service quality perceptions benefit the retailer by increasing their perceptions of its honesty, benevolence and competence.

The results showed that brand love enhanced consumers´ positive behavioural intentions towards brands (willingness to pay more, positive eWOM and resistance to negative information). In other words, consumers act in line with their feelings towards brands. The effects found of brand love on resistance to negative information is in line with other recent research [

15]. Consumers’ loyalty to car brands may cause them to resist negative information. When car dealerships encounter problems (e.g., changed customer expectations that affect perceived service quality, a reputation for charging high prices for spare parts, unfriendly staff) they may be faced with a situation where consumers post negative information on social media. However, emotional factors can affect consumers’ reactions towards unfavourable information about the car dealership. For example, when consumers have highly emotional relationships with brands they become resistant to negative information about them [

38]. Similarly, it has been shown that brand love is a mediator between brand trust and resistance to negative information [

53]. In this sense, positive brand affect can increase consumers´ willingness to pay more, positive eWOM and resistance to negative information.

5.2. Managerial implications

The insights obtained from the study allow us to draw various practical conclusions for automobile retailers.

The study identified specific service personnel traits, that is, politeness, helpfulness, honesty and respectfulness, as key drivers of perceived service quality, given that they increase consumers perceptions of trust in the dealership and customer happiness. These traits enable service personnel to better understand customer needs and listen attentively to their concerns. Thus, automobile retailers should allocate resources to improve their perceived service quality by, first, hiring service personnel who exhibit politeness, helpfulness, honesty and respectfulness and, second, provide training programmes and performance evaluations to current personnel, focused on these traits.

The study highlights the role of trust and customer happiness as powerful drivers of brand love. When consumers trust their car dealerships their car brand love increases, which makes them willing to pay a higher price for their cars and, even, advocate the brand within their social circles. To increase customers’ trust it is vitally important that companies deliver on the promises they make to those customers. Thus, car dealerships should consider conducting advertising campaigns aimed at creating awareness among customers that their prices are fair, they provide convenient services (long opening hours, accessible locations) and that their service centres have staff with the highest technical expertise.

The findings of the study also suggest that car dealerships should provide their customers with pleasurable experiences. The results of the operational service performance dimension showed that, when customers face the inconvenience of waiting a long time for the dealership to deliver the service, they become unhappy. Car dealerships should invest in providing express services so that their customers can save time, which they can then use in more productive ways, which can improve their perceptions of the company´s responsiveness. In addition, to strengthen links with their customers, car dealerships should also improve their online marketing strategies and provide flexible service times.

Brand love acts as a powerful buffer against negative sentiments expressed on social media, providing a layer of protection for the brand's reputation. When customers feel a strong emotional bond with an automotive brand, they are more inclined to actively share positive experiences, reviews and recommendations on their online networks. Automobile industry managers should cultivate brand love among their existing customer bases by providing personalised experiences and exceptional customer service. Brand love can be enhanced by establishing rewards/loyalty programmes for those customers who actively advocate the car dealership brands by spreading positive electronic word of mouth, and by continuously hosting events exclusively for these customers. These gatherings express the dealership´s gratitude to the customers for their continued support and loyalty, and can be used to collect feedback with an eye towards cultivating a community of enthusiastic brand ambassadors. The personal touch, for example, sending birthday wishes to their customers, would generate in them a feel-good factor and encourage them to engage in positive word of mouth.

5.3. Limitations and future research lines

The study has some limitations that open promising avenues for future research. First, the cross-sectional nature of the study can provide only a snapshot of the hypothesised paths; a longitudinal design could be used to identify time-based facets and provide more rigorous empirical support for the hypotheses. Second, we are keenly aware that focusing on a single company and product type (new cars) limits the generalisability of the results (hence, it would be worthwhile to test the model with a sample of second-hand cars). Future studies might validate the results by examining other companies and product categories. For example, it is conceivable that perceived service quality could be a more important issue for service than for product providers, and for hedonic than for utilitarian offers. Third, the present research is limited by the constructs examined. Future studies might delve into other brand-level effects and interactions, such as the role of brand uniqueness and brand desire, to shed light on the potential boundary conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, C.R. and RC.; methodology, M.H. and R.C.; software, R.C.; formal analysis, R.C. and M.H.; writing—original draft, M.H.; supervision, C.R. and R.C.; funding acquisition, C.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (ID grant number: PID2019-111195RB-I00/ AEI / 10.13039/501100011033 0).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy restrictions. This database contains information of customers of Abu Khader Automotive.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Abu Khader Automotive for technical support in the research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Batra, R.; Ahuvia, A.; Bagozzi, R.P. Brand love. Journal of marketing. 2012, 76, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, B.A.; Ahuvia, A.C. Some antecedents and outcomes of brand love. Marketing letters. 2006, 17, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F.; Guzmán, F. Perceived injustice and brand love: the effectiveness of sympathetic vs empathetic responses to address consumer complaints of unjust specific service encounters. Journal of Product & Brand Management. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Le, M.T. The impact of brand love on brand loyalty: the moderating role of self-esteem, and social influences. Spanish Journal of Marketing-ESIC. 2021, 25, 156-80. [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.K.; Eshghi, A.; Sarkar, A. Antecedents and consequences of brand love. Journal of Brand Management. 2013, 20, 325–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A. Analysing the drivers of customer happiness at authorized workshops and improving retention. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services. 2021, 62, 102619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.C.; Yu, A.P.; Le, T.H. Customers focus and impulse buying at night markets. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services. 2021, 60, 102434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulzari, A.; Wang, Y.; Prybutok, V. A green experience with eco-friendly cars: A young consumer electric vehicle rental behavioral model. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services. 2022, 65, 102877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, C.; Scherer, A.; Wangenheim, F.V. Branding access offers: the importance of product brands, ownership status, and spillover effects to parent brands. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science. 2015, 43, 574–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilgard, E.R. The trilogy of mind: Cognition, affection, and conation. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences. 1980, 16, 107–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, H.; Osatuyi, B.; Xu, L. How mobile augmented reality applications affect continuous use and purchase intentions: A cognition-affect-conation perspective. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services. 2021, 63, 102680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Mundel, J. Effects of brand feedback to negative eWOM on brand love/hate: an expectancy violation approach. Journal of Product & Brand Management. 2022, 31, 279-92. [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.M.; Hunt, S.D. The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. Journal of marketing. 1994, 58, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orzan, G.; Platon, O.E.; Stefănescu, C.D.; Orzan, M. Conceptual model regarding the influency of social media marketing communication on brand trust, brand affect and brand loyalty. Economic Computation & Economic Cybernetics Studies & Research. 2016, 50.

- Gültekin, B.; KİLİC, S.I. Repurchasing an Environmental Related Crisis Experienced Automobile Brand: An Examination in the Context of Environmental Consciousness, Brand Trust, Brand Affect, and Resistance to Negative Information. Sosyoekonomi. 2022, 30, 241–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.B.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L. SERVQUAL: A multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. 1988. 1988, 64, 12–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andaleeb, S.S.; Basu, A.K. Technical complexity and consumer knowledge as moderators of service quality evaluation in the automobile service industry. Journal of retailing. 1994, 70, 367–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, J.C.; Malhotra, N.K.; Alpert, F. A two-dimensional model of trust–value–loyalty in service relationships. Journal of retailing and consumer services. 2015, 26, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vacas de Carvalho, L.; Azar, S.L.; Machado, J.C. Bridging the gap between brand gender and brand loyalty on social media: Exploring the mediating effects. Journal of Marketing Management. 2020, 36, 1125–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Q.M.; Raziq, M.M.; Ahmed, S. The role of social media marketing and brand consciousness in building brand loyalty. GMJACS. 2018, 8, 12-. [Google Scholar]

- Karjaluoto, H.; Munnukka, J.; Kiuru, K. Brand love and positive word of mouth: the moderating effects of experience and price. Journal of Product & Brand Management. 2016, 25, 527-37. [CrossRef]

- Homburg, C.; Koschate, N.; Hoyer, W.D. Do satisfied customers really pay more? A study of the relationship between customer satisfaction and willingness to pay. Journal of marketing. 2005, 69, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.C. The impacts of brand experiences on brand loyalty: mediators of brand love and trust. Management Decision. 2017, 55, 915–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bairrada, C.M.; Coelho, A.; Lizanets, V. The impact of brand personality on consumer behavior: the role of brand love. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal. 2019, 23, 30-47. [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, A.; Nayeem, T.; Murshed, F. Brand experience and consumers’ willingness-to-pay (WTP) a price premium: Mediating role of brand credibility and perceived uniqueness. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services. 2018, 44, 100–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Research and Markets. (2023). Jordan Automotive Market: Size, Share, Outlook. Retrieved from https://www.researchandmarkets.com/reports/5713278/jordan-automotive-market-size-share-outlook#.

- Molina-Azorin, J.F.; Guetterman, T.C. Special Issues on Mixed Methods Research: Expanding the Use of Mixed Methods in Disciplines. Journal of Mixed Methods Research. 2023, 17, 234–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martí-Parreño, J.; Galbis-Córdova, A.; Currás-Pérez, R. Teachers’ beliefs about gamification and competencies development: A concept mapping approach. Innovations in education and teaching international. 2021, 58, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, M.; Trochim, W.M. Concept mapping for planning and evaluation. Sage Publications, Inc; 2007. [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, F.; Fuglsang, L.; Sundbo, J.; Jensen, J.F. Tourism practices and experience value creation: The case of a themed attraction restaurant. Tourist Studies. 2020, 20, 271–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royo-Vela, M.; Casamassima, P. The influence of belonging to virtual brand communities on consumers' affective commitment, satisfaction and word-of-mouth advertising: The ZARA case. Online Information Review. 2011, 35, 517–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo-Zegarra, M.; Ruiz-Mafe, C.; Sanz-Blas, S. The effects of mobile advertising alerts and perceived value on continuance intention for branded mobile apps. Sustainability. 2020, 12, 6753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballester, E.; Ruiz-Mafé, C.; Rubio, N. Females’ customer engagement with eco-friendly restaurants in Instagram: the role of past visits. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management. 2023, 35, 2267–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Dholakia, U.M. Antecedents and purchase consequences of customer participation in small group brand communities. International Journal of research in Marketing. 2006, 23, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.A. Measures of emotion. In The measurement of emotions 1989 Jan 1 (pp. 83-111). Academic Press.

- Flavián, C.; Guinalíu, M.; Gurrea, R. The role played by perceived usability, satisfaction and consumer trust on website loyalty. Information & management. 2006, 43, 1-4. [CrossRef]

- Bigne, E.; Andreu, L.; Perez, C.; Ruiz, C. Brand love is all around: loyalty behaviour, active and passive social media users. Current Issues in Tourism. 2020, 23, 1613–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisingerich, A.B.; Rubera, G.; Seifert, M.; Bhardwaj, G. Doing good and doing better despite negative information?:The role of corporate social responsibility in consumer resistance to negative information. Journal of Service Research. 2011, 14, 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohmöller, J.B.; Lohmöller, J.B. Predictive vs. structural modeling: Pls vs. ml. Latent variable path modeling with partial least squares. 1989, 199-226. [CrossRef]

- Hair, J., Jr.; Page, M.; Brunsveld, N. Essentials of business research methods. Routledge; 2019 Nov 5. [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Sinkovics, N.; Sinkovics, R.R. A perspective on using partial least squares structural equation modelling in data articles. Data in Brief. 2023, 48, 109074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the academy of marketing science. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory New York. NY: McGraw-Hill. 1994.

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of marketing research. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, R. The Big Five, happiness, and shopping. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services. 2016, 31, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, T.; Yi, Y. The effect of service quality on customer satisfaction, loyalty, and happiness in five Asian countries. Psychology & Marketing. 2018, 35, 427-42. [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.J.; Chiou, S.C. Dimensions of customer value for the development of digital customization in the clothing industry. Sustainability. 2020, 12, 4639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, L.; Keiningham, T.L.; Buoye, A.; Lariviere, B.; Williams, L.; Wilson, I. Does loyalty span domains? Examining the relationship between consumer loyalty, other loyalties and happiness. Journal of Business Research. 2015, 68, 2464–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.; Hsee, C.K. Hedonomics: On subtle yet significant determinants of happiness. Handbook of Well-being. 2018:248.

- Kumar, A.; Luthra, S.; Khandelwal, D.K.; Mehta, R.; Chaudhary, N.; Bhatia, S. Measuring and improving customer retention at authorised automobile workshops after free services. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services. 2017, 39, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, M.; Kaul, D. Exploring the link between customer experience–loyalty–consumer spend. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services. 2016, 31, 277–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Lü, Y.; Liu, Y.; Gao, W. Ecosystem service value of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau significantly increased during 25 years. Ecosystem services. 2020, 44, 101146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turgut & Gultekin, 2015 Turgut MU, Gultekin B. The critical role of brand love in clothing brands. Journal of Business Economics and Finance. 2015, 4. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).