Submitted:

09 January 2024

Posted:

10 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Primary screening of USDA and TGRC tomato core germplasm collections for resistance to ToBRFV

| Species | USDA PIs | TGRC Accessions | Total number of accessions screened | Number of accessions in resistance/tolerance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solanum arcanum | 1 | 9 | 10 | 0 |

| Solanum chilense | 0 | 17 | 17 | 0 |

| Solanum corneliomulleri | 6 | 11 | 17 | 1 |

| Solanum habrochaites | 17 | 33 | 50 | 4 |

| S. huaylasense | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| Solanum lycopersicum | 10 | 0 | 10 | 0 |

| Solanum lycopersicum var. cerasiforme | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Solanum neorickii | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Solanum pennellii | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Solanum peruvianum | 64 | 9 | 73 | 3 |

| Solanum pimpinellifolium | 136 | 4 | 140 | 31 |

| Solanum subsect. lycopersicon hybrid | 153 | 0 | 153 | 5 |

| Total | 390 | 86 | 476 | 44 |

| Plant ID | Taxonomy | Disease severity index (%) |

| PI 129144 | Solanum corneliomulleri | 0 |

| PI 126445 | Solanum habrochaites | 17.6 |

| PI 209978 | Solanum habrochaites | 0 |

| PI 247087 | Solanum habrochaites | 0 |

| LA 2107 | Solanum habrochaites | 0 |

| PI 306811 | Solanum peruvianum | 16 |

| PI 390667 | Solanum peruvianum | 0 |

| PI 390671 | Solanum peruvianum | 0 |

| PI 127805 | Solanum pimpinellifolium | 14.2 |

| PI 143524 | Solanum pimpinellifolium | 14.2 |

| PI 143527 | Solanum pimpinellifolium | 0 |

| PI 211838 | Solanum pimpinellifolium | 0 |

| PI 230327 | Solanum pimpinellifolium | 0 |

| PI 344102 | Solanum pimpinellifolium | 0 |

| PI 344103 | Solanum pimpinellifolium | 0 |

| PI 346340 | Solanum pimpinellifolium | 0 |

| PI 390692 | Solanum pimpinellifolium | 0 |

| PI 390693 | Solanum pimpinellifolium | 0 |

| PI 390694 | Solanum pimpinellifolium | 0 |

| PI 390695 | Solanum pimpinellifolium | 0 |

| PI 390698 | Solanum pimpinellifolium | 0 |

| PI 390699 | Solanum pimpinellifolium | 18 |

| PI 390700 | Solanum pimpinellifolium | 0 |

| PI 390702 | Solanum pimpinellifolium | 11.4 |

| PI 390710 | Solanum pimpinellifolium | 0 |

| PI 390712 | Solanum pimpinellifolium | 0 |

| PI 390713 | Solanum pimpinellifolium | 0 |

| PI 390714 | Solanum pimpinellifolium | 0 |

| PI 390716 | Solanum pimpinellifolium | 0 |

| PI 390717 | Solanum pimpinellifolium | 0 |

| PI 390720 | Solanum pimpinellifolium | 8.4 |

| PI 390722 | Solanum pimpinellifolium | 0 |

| PI 390723 | Solanum pimpinellifolium | 16 |

| PI 390724 | Solanum pimpinellifolium | 0 |

| PI 390725 | Solanum pimpinellifolium | 3.4 |

| PI 390726 | Solanum pimpinellifolium | 0 |

| PI 390727 | Solanum pimpinellifolium | 0 |

| PI 390750 | Solanum pimpinellifolium | 0 |

| PI 432362 | Solanum pimpinellifolium | 8.8 |

| PI 127799 | Solanum subsect. lycopersicon hybrid | 17.8 |

| PI 129143 | Solanum subsect. lycopersicon hybrid | 0 |

| PI 143522 | Solanum subsect. lycopersicon hybrid | 18 |

| PI 233930 | Solanum subsect. lycopersicon hybrid | 0 |

| PI 237640 | Solanum subsect. lycopersicon hybrid | 3.4 |

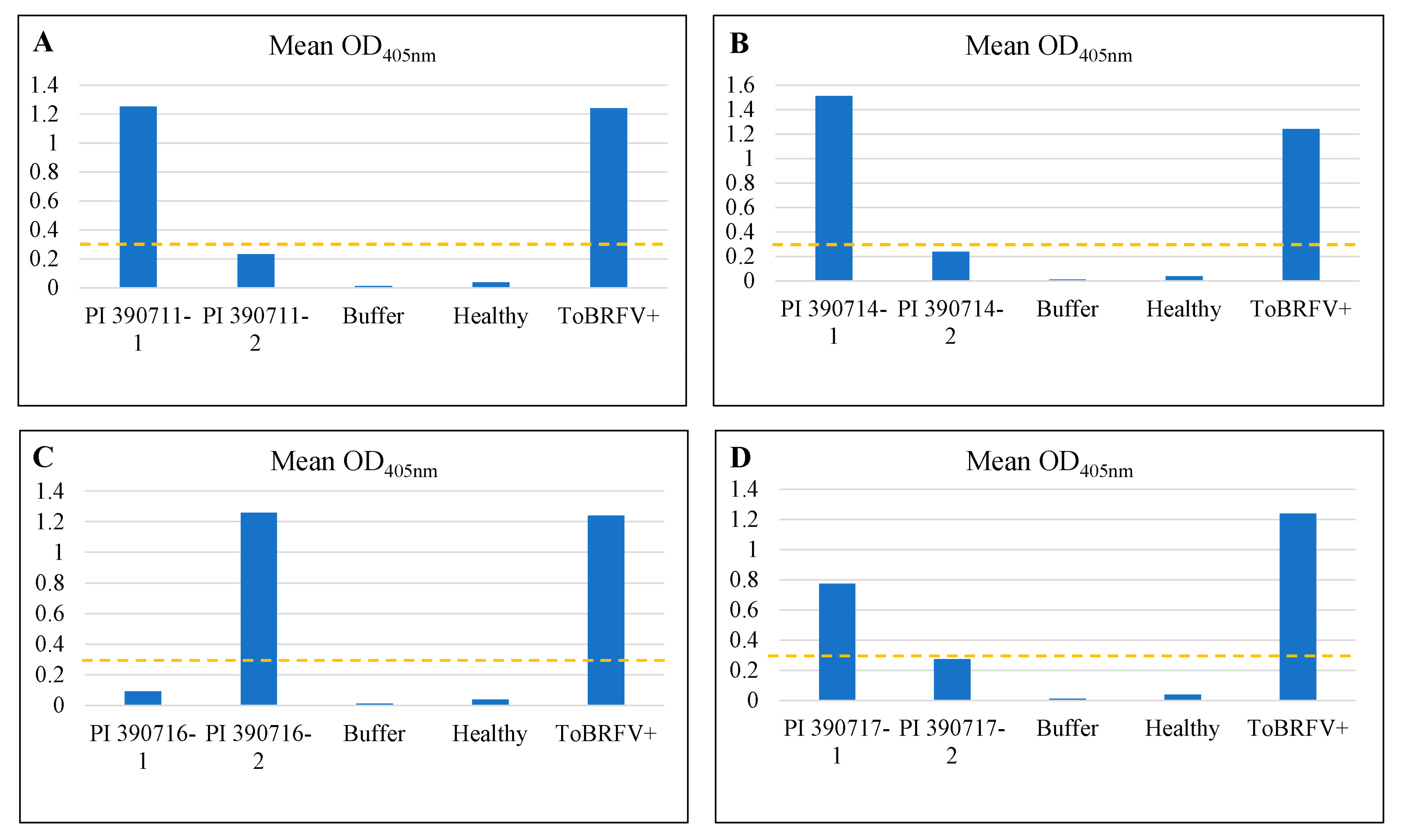

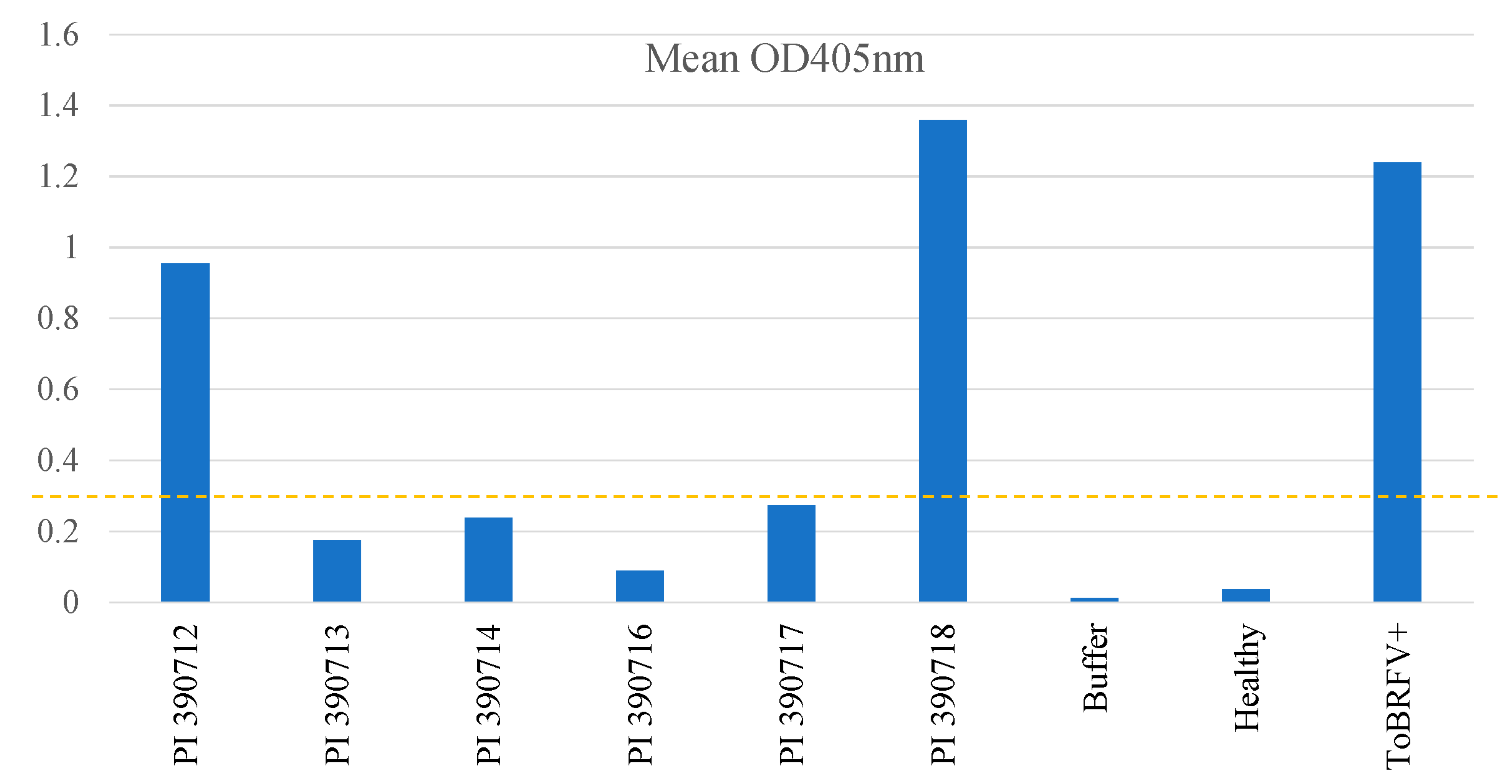

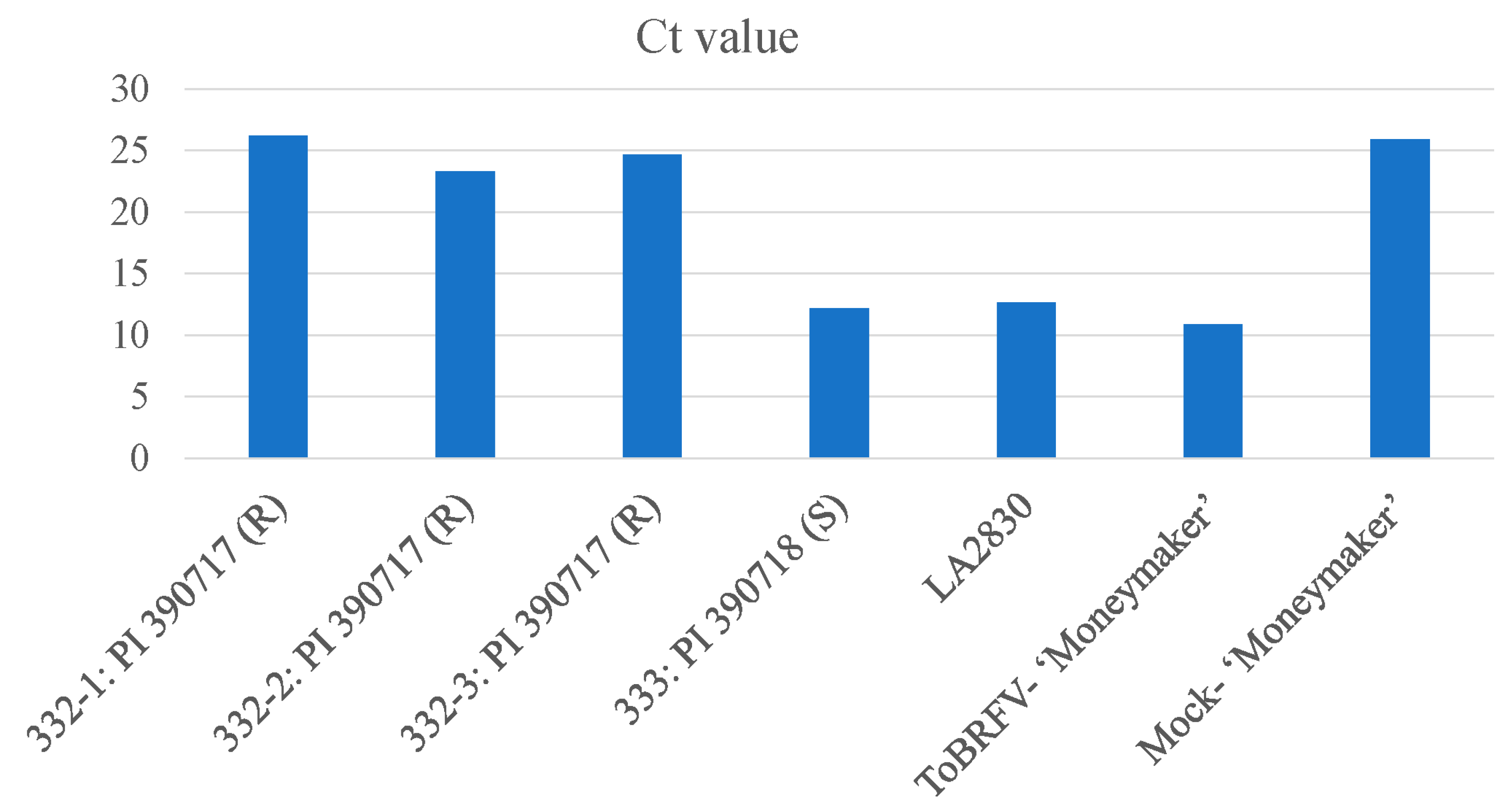

2.2. Rescreening of selected lines to verify their resistant properties to ToBRFV

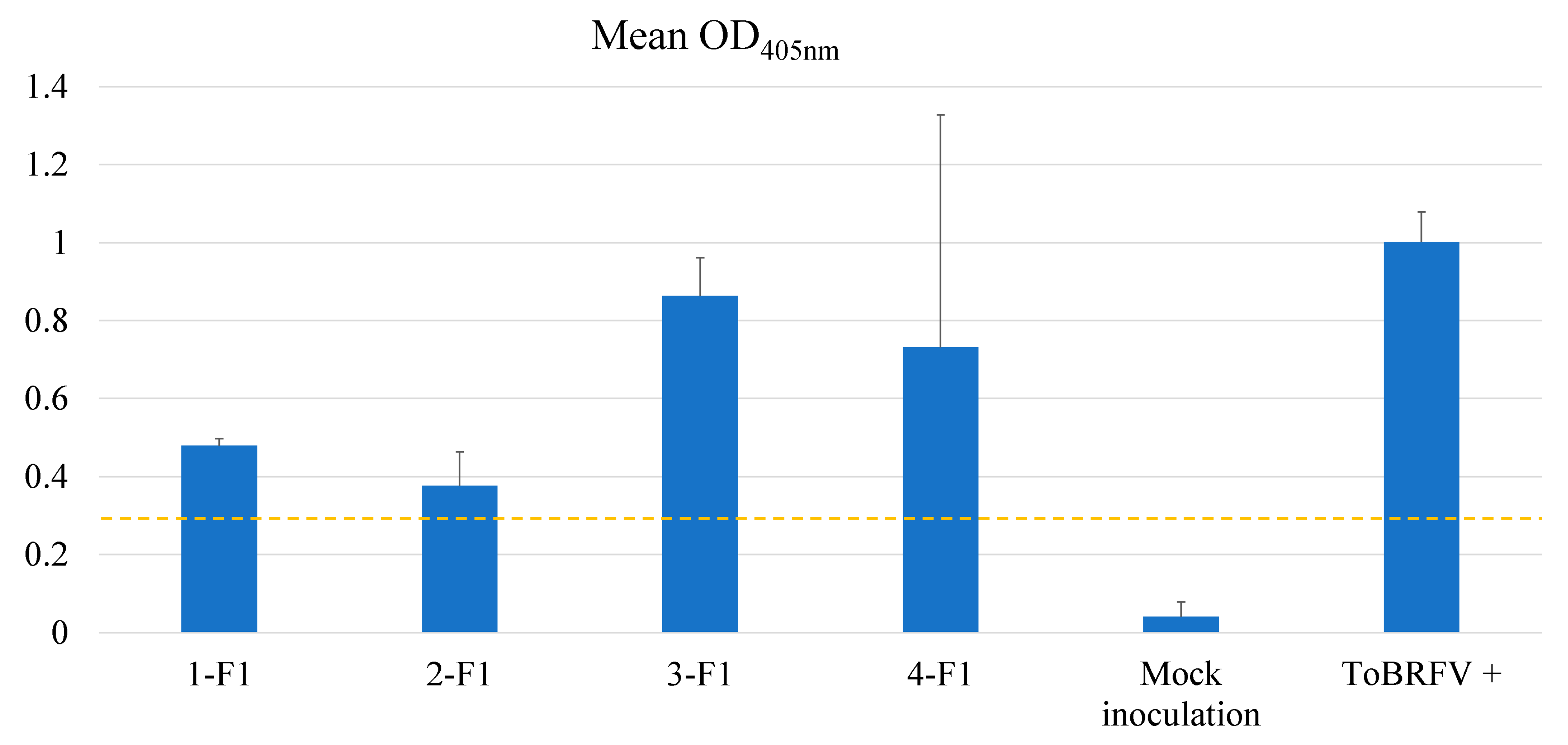

2.3. Testing F1 progenies for their resistance to ToBRFV

3. Discussion

| Zinger et al., 2021 [38] | Kabas et a., 2022 [41] | Jewehan et al., 2022a [39] | Jewehan et al., 2022b [40] | This study | |

| Total lines | 160 | 44 | 636 | 173 | 476 |

| Tolerant lines | S. pimpinellifolium (9); S. Lycopersicum (8) | S. pimpinnelifolium (1); S. penellii (1); and S. chilense (2) | S. pimpinelifolium (26); S. chilense (1); S. lycopersicum var. cerasiforme (4) | S. corneliomulleri (1); S. habrochaites (8); S. peruvianum (3); S. pimpinellifolium (27); and S. subsect. lycopersicon hybrid (5) | |

| Resistant lines | S. lycopersicum (1) | S. ochrantum (5) |

S. habrochaites (9); S. peruvianum (1) |

S. pimpinellifolium (4) |

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant germplasm materials

4.2. Virus culture and mechanical inoculation

4.3. Virus detection through a serological test using Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

4.4. Virus detection using reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

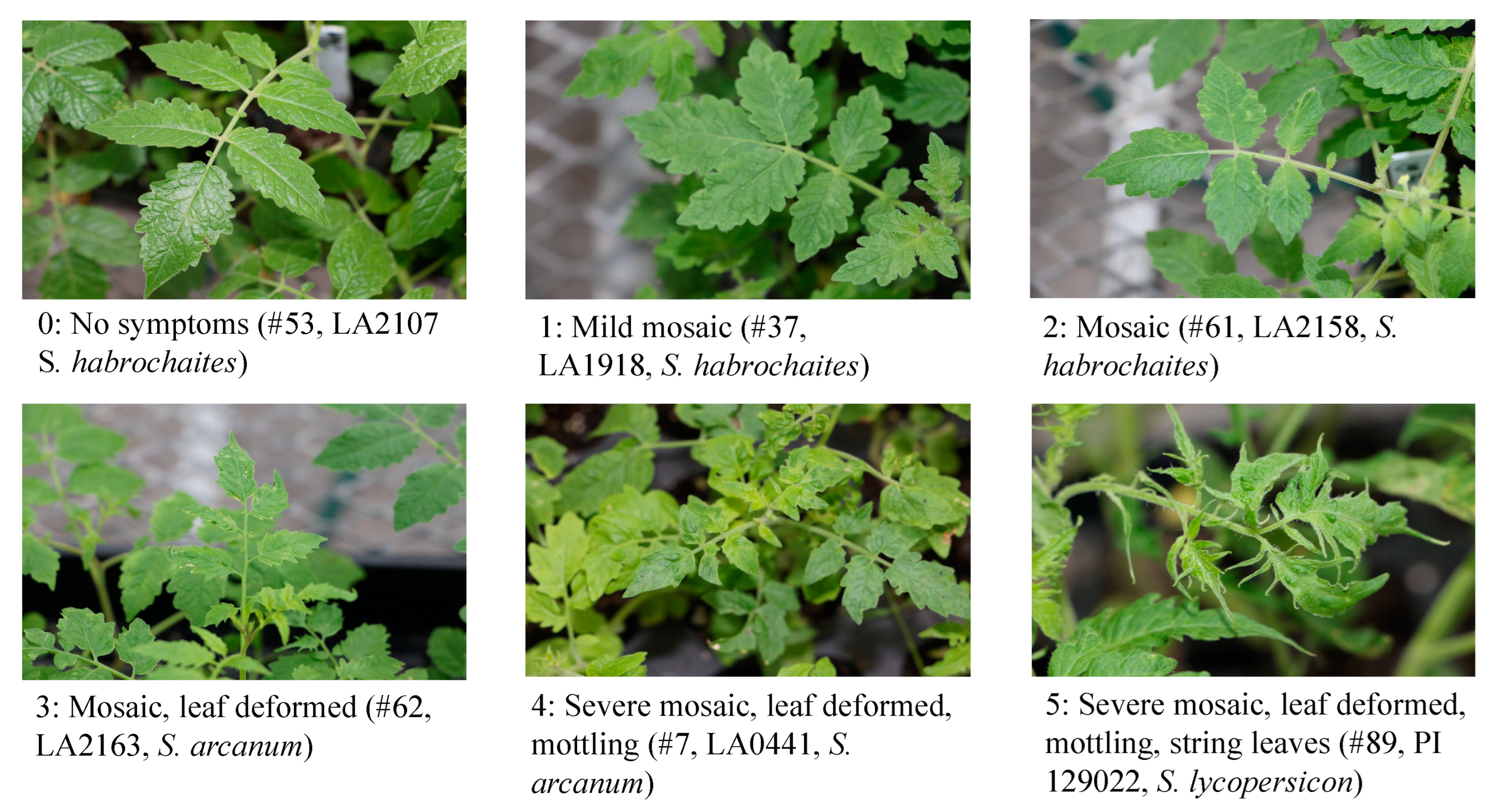

4.5. Disease scoring and data analysis

4.6. Advancing selected resistant lines through self-pollination or cross-pollination to generate F1 plants for evaluation of their inheritability of resistance to ToBRFV

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Salem, N.M.; Jewehan, A.; Aranda, M.A.; Fox, A. Tomato brown rugose fruit virus pandemic. Annual Review of Phytopathology 2023, 61, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Griffiths, J.S.; Marchand, G.; Bernards, M.A.; Wang, A. Tomato brown rugose fruit virus: An emerging and rapidly spreading plant RNA virus that threatens tomato production worldwide. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2022, 23, 1262–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salem, N. M.; Mansour, A. N.; Abdeen, A. O.; Araj, S.; Khrfan, W. I. First report of tomato chlorosis virus infecting tomato crops in Jordan. Plant Disease, 2015, 99, 1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luria, N.; Smith, E.; Reingold, V.; Bekelman, I.; Lapidot, M.; Levin, I.; Elad, N.; Tam, Y.; Sela, N.; Abu-Ras, A.; Ezra, N.; Haberman, A.; Yitzhak, L.; Lachman, O.; Dombrovsky, A. A new israeli tobamovirus isolate infects tomato plants harboring Tm-22 resistance genes. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0170429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abou Kubaa, R.; Choueiri, E.; Heinoun, K.; Cillo, F.; Saponari, M. First report of tomato brown rugose fruit virus infecting sweet pepper in Syria and Lebanon. J. Plant Path. 2022, 104, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkowni, R.; Alabdallah, O.; Fadda, Z. Molecular identification of tomato brown rugose fruit virus in tomato in Palestine. J. Plant Pathol., 2019, 101, 719–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, A.; Rostami, M.; Seifi, S.; Izadpanah, K. First report of tomato brown rugose fruit virus in greenhouse tomato in Iran. New Disease Reports, 2021, 44, e12040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, Z.M.; Salem, N.M.; Ismail, I.D.; Akel, E.H.; Ahmad, A.Y. First report of Tomato brown rugose fruit virus on greenhouse tomato in Syria. Plant Disease, 2022, 106, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabra, A.; Saleh, M.A.A.; Alshahwan, I.M.; Amer, M.A. First report of Tomato brown rugose fruit virus infecting tomato crop in Saudi Arabia. Plant Disease, 2021, 106, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Z.-Y.; Ma, H.-Y.; Han, S.-L.; Geng, C.; Tian, Y.-P.; Li, X.-D. First report of tomato brown rugose fruit virus infecting tomato in China. Plant Disease, 2019, 103, 2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amer, M.A.; Mahmoud, S.Y. First report of tomato brown rugose fruit virus on tomato in Egypt. New Disease Reports, 2020, 41, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaro-Fernández, A.; Castillo, P.; Sanahuja, E.; Rodríguez-Salido, M.C.; Font, M.I. First report of tomato brown rugose fruit virus in tomato in Spain. Plant Disease, 2021, 105, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beris, D.; Malandraki, I.; Kektsidou, O.; Theologidis, I.; Vassilakos, N.; Varveri, C. First report of tomato brown rugose fruit virus infecting tomato in Greece. Plant Disease 2020, 104, 2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidan, H.; Sarikaya, P.; Calis, O. First report of tomato brown rugose fruit virus on tomato in Turkey. New Disease Reports, 2019, 39, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamborg, Z.; Blystad, D.-R. The first report of Tomato brown rugose fruit virus in tomato in Norway. Plant Disease, 2022, 106, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahillon, M.; Kellenberger, I.; Dubuis, N.; Brodard, J.; Bunter, M.; Weibel, J.; Sandrini, F.; Schumpp, O. First report of Tomato brown rugose fruit virus in tomato in Switzerland. New Disease Reports, 2022, 45, e12065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzel, W.; Knierim, D.; Winter, S.; Hamacher, J.; Heupel, M. First report of tomato brown rugose fruit virus infecting tomato in Germany. New Disease Reports, 2019, 39, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orfanidou, C.G.; Cara, M.; Merkuri, J.; Papadimitriou, K.; Katis, N.I.; Maliogka, V.I. First report of tomato brown rugose fruit virus in tomato in Albania. J Plant Path., 2022, 104, 855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panno, S.; Caruso, A. G.; Davino, S. First report of tomato brown rugose fruit virus on tomato crops in Italy. Plant Disease, 2019, 103, 1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skelton, A.; Buxton-Kirk, A.; Ward, R.; Harju, V.; Frew, L.; Fowkes, A.; Long, M.; Negus, A.; Forde, S.; Adams, I. P.; Pufal, H.; McGreig, S.; Weekes, R.; Fox, A. First report of Tomato brown rugose fruit virus in tomato in the United Kingdom. New Disease Reports, 2019, 40, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skelton, A.; Gentit, P.; Porcher, L.; Visage, M.; Fowkes, A.; Adams, I.P.; Harju, V.; Webster, G.; Pufal, H.; McGreig, S.; Ward, R.; Fox, A. First report of Tomato brown rugose fruit virus in tomato in France. New Disease Reports, 2022, 45, e12061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Vossenberg, B. T. L. H.; Visser, M.; Bruinsma, M.; Koenraadt, H.M.S. , Westenberg, M.; Botermans, M. Real-time tracking of Tomato brown rugose fruit virus (ToBRFV) outbreaks in the Netherlands using Nextstrain. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0234671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cambrón-Crisantos, J.M.; Rodríguez-Mendoza, J.; Valencia-Luna, J.B.; Alcasio-Rangel, S.; García-Ávila, C.J.; López-Buenfil, J.A.; Ochoa-Martínez, D.L. First report of tomato brown rugose fruit virus (ToBRFV) in Michoacan, Mexico. Revista Mexicana de Fitopatología, 2018, 37, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho-Beltrán, E.; Pérez-Villarreal, A.; Leyva-López, N.E.; Rodríguez-Negrete, E.A.; Ceniceros-Ojeda, E.A.; Méndez-Lozano, J. Occurrence of tomato brown rugose fruit virus infecting tomato crops in Mexico. Plant Disease, 2019, 103, 1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, K.-S.; Tian, T.; Gurung, S.; Salati, R.; Gilliard, A. First report of tomato brown rugose fruit virus infecting greenhouse tomato in the United States. Plant Disease, 2019, 103, 1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkes, A.; Fu, H.; Feindel, D.; Harding, M.; Feng, J. Development and evaluation of a loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) assay for the detection of Tomato brown rugose fruit virus (ToBRFV). PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0230403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, K.K.; Velez-Climent, M.; Soria, P.; Batuman, O.; Mavrodieva, V.; Wei, G.; Zhou, J.; Adkins, A.; McVay, J. Frist report of tomato brown rugose fruit virus infecting tomato in Florida, USA. New Disease Report 2021, 44, e12028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obregón, V.G. , Ibañez, J. M., Lattar, T.E., Juszczak, S., Groth-Helms, D. First report of tomato brown rugose fruit virus in tomato in Argentina. New Disease Reports 2023, 48, e12203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomato brown rugose fruit virus (ToBRFV) datasheet. EPPO Global Database. Available online: https://gd.eppo.int/taxon/TOBRFV/datasheet (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- Fraser, R.S.S.; Loughlin, S.A.R. Resistance to tobacco mosaic virus in tomato: Effects of the Tm-1 gene on virus multiplication. J. General. Virol. 1980, 48, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, F.O. Inheritance of resistance to infection by tobacco-mosaic virus in tomato. Phytopathology 1954, 44, 640–642. [Google Scholar]

- Pelham, J. Strain-genotype interaction of tobacco mosaic virus in tomato. Ann. Appl. Biol. 1972, 71, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Ronde, D.; Butterbach, P.; Kormelink, R. Dominant resistance against plant viruses. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfitzner, A.J.P. Resistance to tobacco mosaic virus and tomato mosaic virus in tomato. In Natural Resistance Mechanisms of Plants to Viruses; G. Loebenstein, J.P. Carr, Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands,, 2006; pp. 399–413. [Google Scholar]

- Maayan, Y.; Pandaranayaka, E. P. J.; Srivastava, D. A.; Lapidot, M.; Levin, I.; Dombrovsky, A.; Harel, A. Using genomic analysis to identify tomato Tm-2 resistance-breaking mutations and their underlying evolutionary path in a new and emerging tobamovirus. Archives of Virology, 2018, 163, 1863–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanda, B.; Gilliard, A.; Jaiswal, N.; Ling, K.-S. Comparative analysis of host range, ability to infect tomato cultivars with Tm-22 gene, and real-time reverse transcription PCR detection of tomato brown rugose fruit virus. Plant Disease 2021a, 105, 3643–3652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, L.J. Transfer of a dominant type of resistance to the four known Ohio pathogenic strains of tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) from Lycopersicon peruvianum to L. esculentum. Phytopathology 1963, 53, 869. [Google Scholar]

- Paudel, D. B.; Sanfacon, H. Exploring the diversity of mechanisms associated with plant tolerance to virus infection. Frontiers in Plant Science, 2018, 9, 1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, B.-C.; Yeam, I.; Jahn, M. M. Genetics of plant virus resistance. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol., 2005, 43, 581–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponz, F.; Bruening, G. Mechanisms of resistance to plant viruses. Ann. Rev. Phytopathol. 1986, 24, 355–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calil, I. P.; Fontes, E. P. B. Plant immunity against viruses: Antiviral immune receptors in focus. Ann. Bot. 2017, 119, 711–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinger, A.; Lapidot, M.; Harel, A.; Doron-Faigenboim, A.; Gelbart, D.; Levin, I. Identification and mapping of tomato genome loci controlling tolerance and resistance to tomato brown rugose fruit virus. Plants, 2021, 10, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jewehan, A.; Salem, N.; Tóth, Z.; Salamon, P.; Szabó, Z. Screening of Solanum (sections Lycopersicon and Juglandifolia) germplasm for reactions to the tomato brown rugose fruit virus (ToBRFV). J. Plant Dis. & Protect. 2022a, 129, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jewehan, A.; Salem, N.; Tóth, Z.; et al. Evaluation of responses to tomato brown rugose fruit virus (ToBRFV) and selection of resistant lines in Solanum habrochaites and Solanum peruvianum germplasm. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 2022b, 88, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabas, A.; Fidan, H.; Kucukaydin, H.; Atan, H.N.; Kabas, A.; Fidan, H.; Kucukaydin, H.; Atan, H. N. Screening of wild tomato species and interspecific hybrids for resistance/tolerance to Tomato brown rugose fruit virus (ToBRFV). Chilean Journal of Agricultural Research, 2022, 82, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dombrovsky, A.; Smith, E. Seed Transmission of Tobamoviruses: Aspects of Global Disease Distribution. Interchopen 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanda, B.; Shamimuzzaman, M.; Gilliard, A.; Ling, K.-S. Effectiveness of disinfectants against the spread of tobamoviruses: Tomato brown rugose fruit virus and Cucumber green mottle mosaic virus. Virol. J. 2021b. 18, 7. [CrossRef]

- Davino, S.; Caruso, A.G.; Bertacca, S.; Barone, S.; Panno, S. Tomato brown rugose fruit virus: Seed transmission rate and efficacy of different seed disinfection treatments. Plants 2020, 9, 1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dombrovsky, A.; Mor, N.; Gantz, S.; Lachman, O.; Smith, E. Disinfection Efficacy of Tobamovirus-Contaminated Soil in Greenhouse-Grown Crops. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlers, J.; Zarghani, S.N.; Kroschewski, B.; Büttner, C.; Bandte, M. Cleaning of Tomato brown rugose fruit virus (ToBRFV) from contaminated clothing of greenhouse employees. Horticulturae 2022a, 8, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlers, J.; Zarghani, S. N.; Kroschewski, B.; Büttner, C.; Bandte, M. Decontamination of tomato brown rugose fruit virus-contaminated shoe soles under practical conditions. Horticulturae 2022b, 8, 1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, K.-S.; Gilliard, A.C.; Zia, B. Disinfectants useful to manage the emerging tomato brown rugose fruit virus in greenhouse tomato production. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Díaz, C. I.; Zamora-Macorra, E. J.; Ochoa-Martínez, D. L.; González-Garza, R. Disinfectants effectiveness in Tomato brown rugose fruit virus (ToBRFV) transmission in tobacco plants. Rev. Mex. Fitopatol. (Mexican Journal of Phytopathology) 2022, 40, 240–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samarah, N.; Sulaiman, A.; Salem, N.M.; et al. Disinfection treatments eliminated tomato brown rugose fruit virus in tomato seeds. Eur. J. Plant Pathol., 2021, 159, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kole, C. Wild crop relatives: Genomic and breeding resources: Vegetables. Springer: Berlin., 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chanda, B.; Rivera, Y.; Nunziata, S.O.; Galvez, M.E.; Gilliard, A.C.; Ling, K.-S. Complete genome sequence of a tomato brown rugose fruit virus isolated in the United States. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 2020, 9, e00630–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).