Submitted:

10 January 2024

Posted:

11 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1. Materials and Methods

1.1. Study Subjects

1.1. Demographics and Anthropometric Measures

1.1. Knee Pain, Low Back Pain, and Regular Exercise

1.1. Statistical Analyses

1. Results

1. Discussion

1. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Woolf AD, Pfleger B. Burden of major musculoskeletal conditions. Bull World Health Organ. 2003, 81(9), 646-56.

- Cimmino MA, Ferrone C, Cutolo M. Epidemiology of chronic musculoskeletal pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2011, 25(2), 173-83. [CrossRef]

- Fejer R, Ruhe A. What is the prevalence of musculoskeletal problems in the elderly population in developed countries? A systematic critical literature review. Chiropr Man Therap. 2012, 20, 1-52. [CrossRef]

- Blyth FM, Briggs AM, Schneider CH, Hoy DG, March LM. The global burden of musculoskeletal pain—Where to from here? Am J Public Health. 2019, 109(1), 35–40. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briggs AM, Cross MJ, Hoy DG, Sànchez-Riera L, Blyth FM, Woolf AD, March L. Musculoskeletal health conditions represent a global threat to healthy aging: A report for the 2015 World Health Organization world report on ageing and health. Gerontologist. 2016, 56 (suppl_2), S243-S55. [CrossRef]

- Andersen RE, Crespo CJ, Ling SM, Bathon JM, Bartlett SJ. Prevalence of significant knee pain among older Americans: Results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999, 47(12), 1435-8. [CrossRef]

- Sokka T, Abelson B, Pincus T. Mortality in rheumatoid arthritis: 2008 update. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2008, 26 (5 Suppl 51), S35-61.

- Rasch EK, Hirsch R, Paulose-Ram R, Hochberg MC. Prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis in persons 60 years of age and older in the United States: Effect of different methods of case classification. Arthritis & Rheumatism: Official Journal of the American College of Rheumatology. 2003, 48(4), 917-26. [CrossRef]

- Leyland KM, Gates LS, Sanchez-Santos MT, Nevitt MC, Felson D, Jones G; et al. Knee osteoarthritis and time-to all-cause mortality in six community-based cohorts: An international meta-analysis of individual participant-level data. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2021, 33, 529-45. [CrossRef]

- Roseen EJ, Rajendran I, Stein P, Fredman L, Fink HA, LaValley MP, Saper RB. Association of back pain with mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. J Gen Intern Med. 2021, 36, 3148-58. [CrossRef]

- Stubbs B, Binnekade TT, Soundy A, Schofield P, Huijnen IP, Eggermont LH. Are older adults with chronic musculoskeletal pain less active than older adults without pain? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain Medicine. 2013, 14(9), 1316-31. [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner RN, Waters DL, Gallagher D, Morley JE, Garry PJ. Predictors of skeletal muscle mass in elderly men and women. Mech Ageing Dev. 1999, 107(2), 123-36. [CrossRef]

- Chuang S-Y, Chang H-Y, Lee M-S, Chen RC-Y, Pan W-H. Skeletal muscle mass and risk of death in an elderly population. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2014, 24(7), 784-91. [CrossRef]

- Pan F, Tian J, Scott D, Cicuttini F, Jones G. Muscle function, quality, and relative mass are associated with knee pain trajectory over 10.7 years. Pain. 2022, 163(3), 518-25. [CrossRef]

- Law LF, Sluka KA. How does physical activity modulate pain? Pain. 2017, 158(3), 369. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park JH, Lim S, Lim J, Kim K, Han M, Yoon IY; et al. An overview of the Korean longitudinal study on health and aging. Psychiatry Investig. 2007, 4(2), 84.

- Tg, L. Anthropometric standardization reference manual. Human kinetics books. 1988:55-68.

- Lukaski HC, Johnson PE, Bolonchuk WW, Lykken GI. Assessment of fat-free mass using bioelectrical impedance measurements of the human body. Am J Clin Nutr. 1985, 41(4), 810-7. [CrossRef]

- Mijnarends DM, Meijers JM, Halfens RJ, ter Borg S, Luiking YC, Verlaan S; et al. Validity and reliability of tools to measure muscle mass, strength, and physical performance in community-dwelling older people: A systematic review. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013, 14(3), 170-8. [CrossRef]

- Expert Panel on Detection E, Adults ToHBCi. Executive Summary of the Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III. JAMA. 2001, 285(19), 2486-97. [CrossRef]

- Lee SY, Park HS, Kim DJ, Han JH, Kim SM, Cho GJ; et al. Appropriate waist circumference cutoff points for central obesity in Korean adults. iabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007, 75(1), 72–80. [CrossRef]

- Bellamy, N. Validation study of WOMAC: A health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient-relevant outcomes following total hip or knee arthroplasty in osteoarthritis. J Orthop Rheumatol. 1988, 1, 95–108. [Google Scholar]

- Fairbank JC, Couper J, Davies JB, O'Brien JP. The Oswestry low back pain disability questionnaire. Physiotherapy. 1980, 66(8), 271-3.

- Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjöström M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE; et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003, 35(8), 1381-95. [CrossRef]

- Dahlhamer J, Lucas J, Zelaya C, Nahin R, Mackey S, DeBar L; et al. Prevalence of Chronic Pain and High-Impact Chronic Pain Among Adults - United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018, 67(36), 1001-6. [CrossRef]

- Blyth FM, Noguchi N. Chronic musculoskeletal pain and its impact on older people. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2017, 31(2), 160-8. [CrossRef]

- Eggermont LH, Bean JF, Guralnik JM, Leveille SG. Comparing pain severity versus pain location in the MOBILIZE Boston study: Chronic pain and lower extremity function. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009, 64(7), 763-70. [CrossRef]

- Croft P, Jordan K, Jinks C. "Pain elsewhere" and the impact of knee pain in older people. Arthritis Rheum. 2005, 52(8), 2350-4. [CrossRef]

- Rundell SD, Patel KV, Krook MA, Heagerty PJ, Suri P, Friedly JL; et al. Multi-site Pain Is Associated with Long-term Patient-Reported Outcomes in Older Adults with Persistent Back Pain. Pain Med. 2019, 20(10), 1898-906. [CrossRef]

- de Vitta A, Machado Maciel N, Bento TPF, Genebra C, Simeão S. Multisite musculoskeletal pain in the general population: A cross-sectional survey. Sao Paulo Med J. 2022, 140(1), 24–32. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen L, Ferreira ML, Nassar N, Preen DB, Hopper JL, Li S; et al. Association of chronic musculoskeletal pain with mortality among UK adults: A population-based cohort study with mediation analysis. EClinicalMedicine. 2021, 42. [CrossRef]

- Patterson R, McNamara E, Tainio M, de Sá TH, Smith AD, Sharp SJ; et al. Sedentary behaviour and risk of all-cause, cardiovascular and cancer mortality, and incident type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and dose response meta-analysis. Eur J Epidemiol. 2018, 33(9), 811-29. [CrossRef]

- Martin RR, Hadjistavropoulos T, McCreary DR. Fear of pain and fear of falling among younger and older adults with musculoskeletal pain conditions. Pain Res Manag. 2005, 10(4), 211-9. [CrossRef]

- Karttunen N, Lihavainen K, Sipilä S, Rantanen T, Sulkava R, Hartikainen S. Musculoskeletal pain and use of analgesics in relation to mobility limitation among community-dwelling persons aged 75 years and older. Eur J Pain. 2012, 16(1), 140-9. [CrossRef]

- Panhale VP, Gurav RS, Nahar SK. Association of Physical Performance and Fear-Avoidance Beliefs in Adults with Chronic Low Back Pain. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2016, 6(6), 375-9. [CrossRef]

- Leveille SG, Guralnik JM, Hochberg M, Hirsch R, Ferrucci L, Langlois J; et al. Low back pain and disability in older women: Independent association with difficulty but not inability to perform daily activities. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1999, 54(10), M487-93. [CrossRef]

- Kitayuguchi J, Kamada M, Hamano T, Nabika T, Shiwaku K, Kamioka H; et al. Association between knee pain and gait speed decline in rural J apanese community-dwelling older adults: 1-year prospective cohort study. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2016, 16(1), 55–64. [CrossRef]

- Yanardag M, Şimşek TT, Yanardag F. Exploring the Relationship of Pain, Balance, Gait Function, and Quality of Life in Older Adults with Hip and Knee Pain. Pain Manag Nurs. 2021, 22(4), 503-8. [CrossRef]

- Biswas A, Oh PI, Faulkner GE, Bajaj RR, Silver MA, Mitchell MS, Alter DA. Sedentary time and its association with risk for disease incidence, mortality, and hospitalization in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2015, 162(2), 123-32. [CrossRef]

- Piercy KL, Troiano RP, Ballard RM, Carlson SA, Fulton JE, Galuska DA; et al. The physical activity guidelines for Americans. JAMA. 2018, 320(19), 2020-8. [CrossRef]

- Zhao M, Veeranki SP, Magnussen CG, Xi B. Recommended physical activity and all cause and cause specific mortality in US adults: Prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2020, 370, m2031. [CrossRef]

- Tieland M, Trouwborst I, Clark BC. Skeletal muscle performance and ageing. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2018, 9(1), 3–19. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen CP, Hirsch MS, Moeny D, Kaul S, Mohamoud M, Joffe HV. Testosterone and "Age-Related Hypogonadism"--FDA Concerns. N Engl J Med. 2015, 373(8), 689-91. [CrossRef]

- Hermann M, Berger P. Hormonal changes in aging men: A therapeutic indication? Exp Gerontol. 2001, 36(7), 1075-82. [CrossRef]

- Curcio F, Ferro G, Basile C, Liguori I, Parrella P, Pirozzi F; et al. Biomarkers in sarcopenia: A multifactorial approach. Exp Gerontol. 2016, 85, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell WK, Williams J, Atherton P, Larvin M, Lund J, Narici M. Sarcopenia, dynapenia, and the impact of advancing age on human skeletal muscle size and strength; a quantitative review. Front Physiol. 2012, 3, 260. [CrossRef]

- Wang DXM, Yao J, Zirek Y, Reijnierse EM, Maier AB. Muscle mass, strength, and physical performance predicting activities of daily living: A meta-analysis. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2020, 11(1), 3–25. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger MJ, Doherty TJ. Sarcopenia: Prevalence, mechanisms, and functional consequences. Interdiscip Top Gerontol. 2010, 37, 94–114. [CrossRef]

- Zhou HH, Liao Y, Peng Z, Liu F, Wang Q, Yang W. Association of muscle wasting with mortality risk among adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2023, 14(4), 1596-612. [CrossRef]

- Stowe RP, Peek MK, Cutchin MP, Goodwin JS. Plasma cytokine levels in a population-based study: Relation to age and ethnicity. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010, 65(4), 429-33. [CrossRef]

- Zhang JM, An J. Cytokines, inflammation, and pain. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 2007, 45(2), 27–37. [CrossRef]

| Total (n=1000) | Survivor (n = 829) |

Non-Survivor (n = 171) |

P-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) (n = 1000) | 76.3 ± 8.7 | 74.8 ± 8.1 | 83.7 ± 7.8 | < 0.001∗ | |

| Sex (n = 1000) | 0.061 | ||||

| Male | 441 (44.1) | 354 (42.7) | 87 (50.9) | ||

| Female | 559 (55.9) | 475 (57.3) | 84 (49.1) | ||

| BMI (m2/kg) (n = 871) | 24.0 ± 3.3 | 24.1 ± 3.3 | 22.9 ± 3.3 | < 0.001∗ | |

| ASM (kg) (n = 877) | 12.8 ± 3.3 | 12.9 ± 3.3 | 12.3 ± 3.5 | 0.098 | |

| Metabolic syndrome (n = 996) | 0.753 | ||||

| No | 631 (63.4) | 521 (63.1) | 110 (64.7) | ||

| Yes | 365 (36.6) | 305 (36.9) | 60 (36.3) | ||

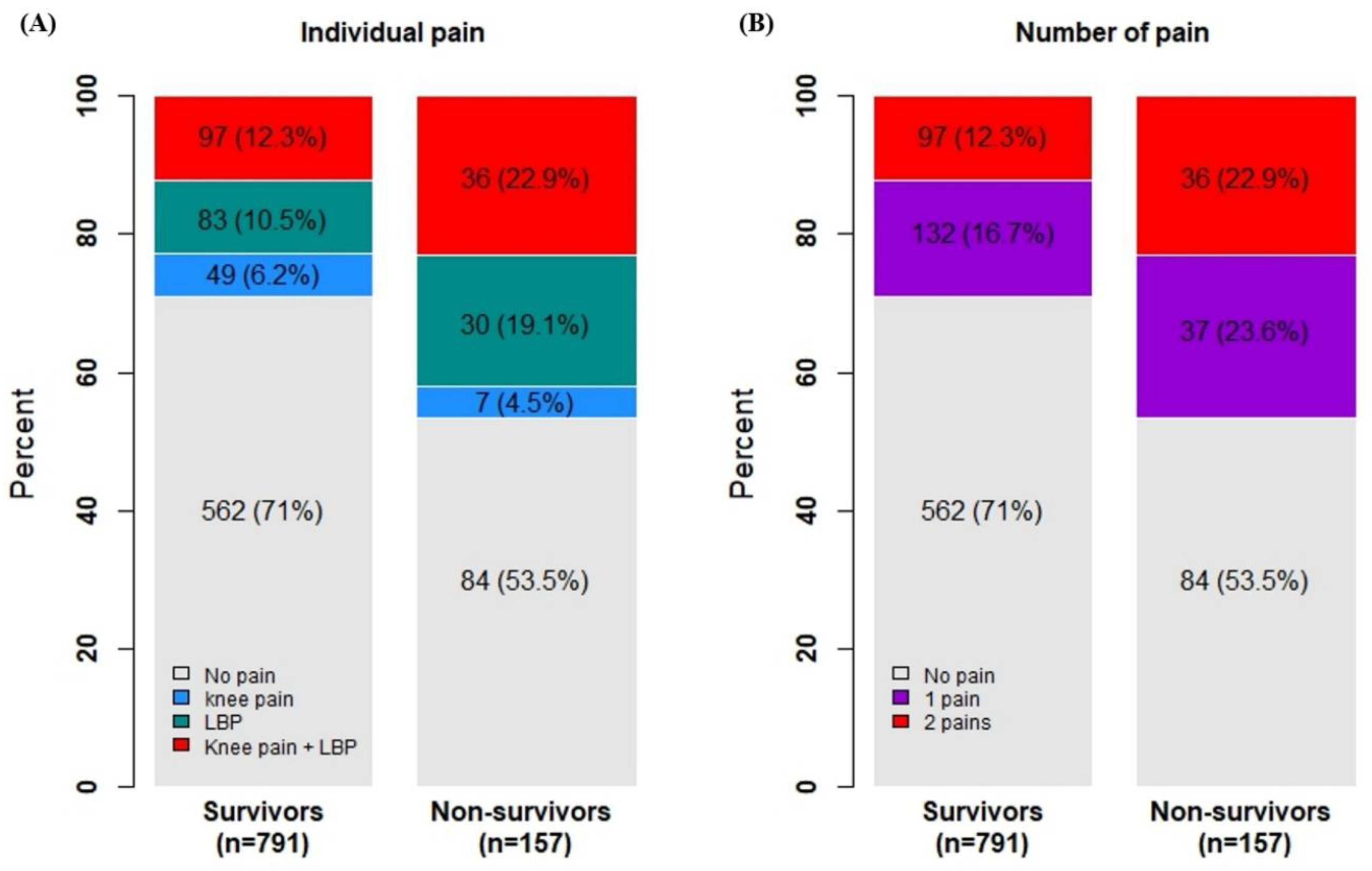

| Low back pain (n = 950) | < 0.001∗ | ||||

| No | 703 (74.0) | 612 (77.3) | 91 (57.6) | ||

| Yes | 247 (26.0) | 180 (22.7) | 67 (42.4) | ||

| Knee pain (n = 949) | 0.016∗ | ||||

| No | 76.0 (80.1) | 645 (81.5) | 115 (72.8) | ||

| Yes | 189 (19.9) | 146 (18.5) | 43 (27.2) | ||

| Alcohol (n = 992) | 0.185 | ||||

| No | 761 (76.7) | 625 (75.8) | 136 (81.0) | ||

| Yes | 231 (23.3) | 199 (24.2) | 32 (19.0) | ||

| Smoking (n=1000) | 1.000 | ||||

| No | 711 (71.1) | 589 (71.0) | 122 (71.3) | ||

| Yes | 289 (28.9) | 240 (29.0) | 49 (28.7) | ||

| Regular exercise (n = 989) | < 0.001∗ | ||||

| No | 492 (49.7) | 377 (45.9) | 115 (68.5) | ||

| Yes | 497 (50.3) | 444 (54.1) | 53 (31.5) | ||

| Variables | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Low Back Pain | Knee Pain | Regular Exercise |

| Age | 0.220** | 0.160** | 0.152** |

| Sex | 0.255** | 0.279** | 0.291** |

| BMI | -0.008 | 0.086* | 0.035 |

| ASM | -0.245** | -0.236** | 0.311** |

| Metabolic syndrome | 0.091** | 0.148** | -0.069** |

| Low back pain | - | 0.506** | -0.245** |

| Knee pain | 0.506** | - | -0.264** |

| Alcohol | -0.127** | -0.176** | 0.129** |

| Smoking | -0.122** | -0.163** | 0.119** |

| Regular exercise | -0.245** | -0.264** | - |

| Individual pain† | MSK pain‡ | Regular exercise | |

| Mortality | 0.164** | 0.145** | -0.169** |

| Characteristics | Univariate Model | Multivariate Model 1§ | Multivariate Model 2⁋ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |

| Age | 1.133 (1.108-1.159) | < 0.001 | 1.095 (1.065-1.126) | < 0.001 | 1.095 (1.065-1.126) | < 0.001 |

| Sex (Female)* | 0.720 (0.517-1.001) | 0.051 | 0.138 (0.063-0.302) | < 0.001 | 0.138 (0.063-0.302) | < 0.001 |

| Metabolic syndrome | 0.932 (0.660-1.315) | 0.688 | ||||

| BMI | 0.897 (0.894-1.010) | 0.001 | 0.299 | 0.299 | ||

| ASM | 0.950 (0.383-0.751) | 0.098 | 0.822 (0.732-0.923) | 0.001 | 0.822 (0.732-0.923) | 0.001 |

| Low back pain | 2.503(1.752-3.576) | < 0.001 | 0.442 | |||

| Knee pain | 1.652 (1.114-2.499) | 0.012 | 0.956 | |||

| Alcohol | 0.739 (0.487-1.121) | 0.155 | 0.235 | 0.235 | ||

| Smoking | 0.986 (0.685-1.418) | 0.938 | ||||

| Regular exercise | 0.391 (0.275-0.557) | < 0.001 | 0.465 (0.287-0.754) | 0.002 | 0.465 (0.287-0.754) | 0.002 |

| MSK pain (1)† | 1.875 (1.219-2.885) | 0.004 | 0.979 | |||

| MSK pain (2)‡ | 2.483 (1.590-3.879) | < 0.001 | 0.661 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).