Submitted:

10 January 2024

Posted:

10 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Personality and emotional self-efficacy

1.2. Emotion regulation

1.3. Emotion regulation, emotional self-efficacy and personality

2. Aims and hypotheses

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

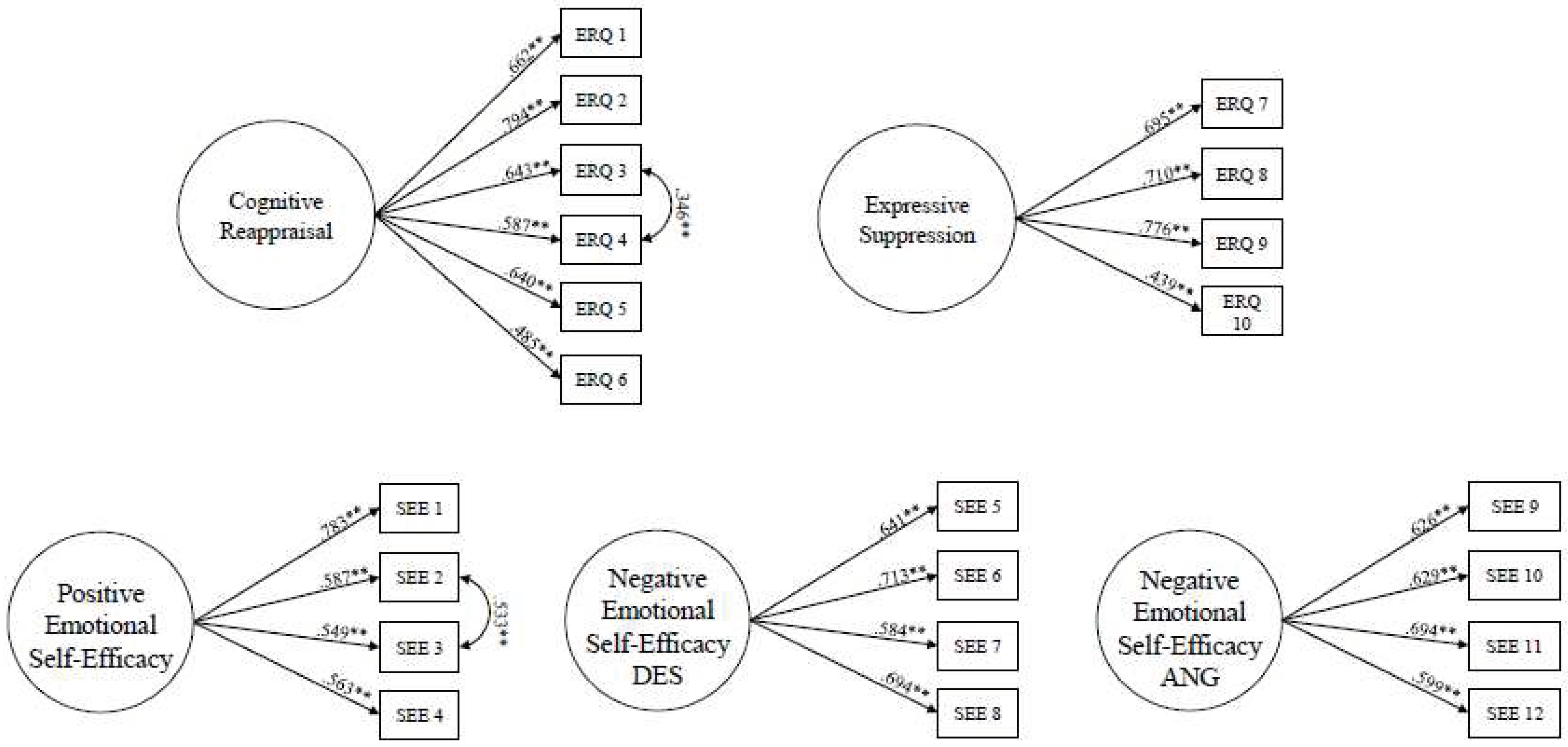

3.2. Instruments

- A)

- Extraversion and neuroticism have direct effects on positive affect and negative affect, while openness, conscientiousness and agreeableness may have an instrumental (indirect) effect on positive affect and negative affect [64]. This justifies the use of these two variables as mediating variables [64]. Additionally, previous investigations have already used extraversion and neuroticism as mediating variables [65,66].

- B)

3.3. Procedure

3.4. Data analysis

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive results and correlational analyses

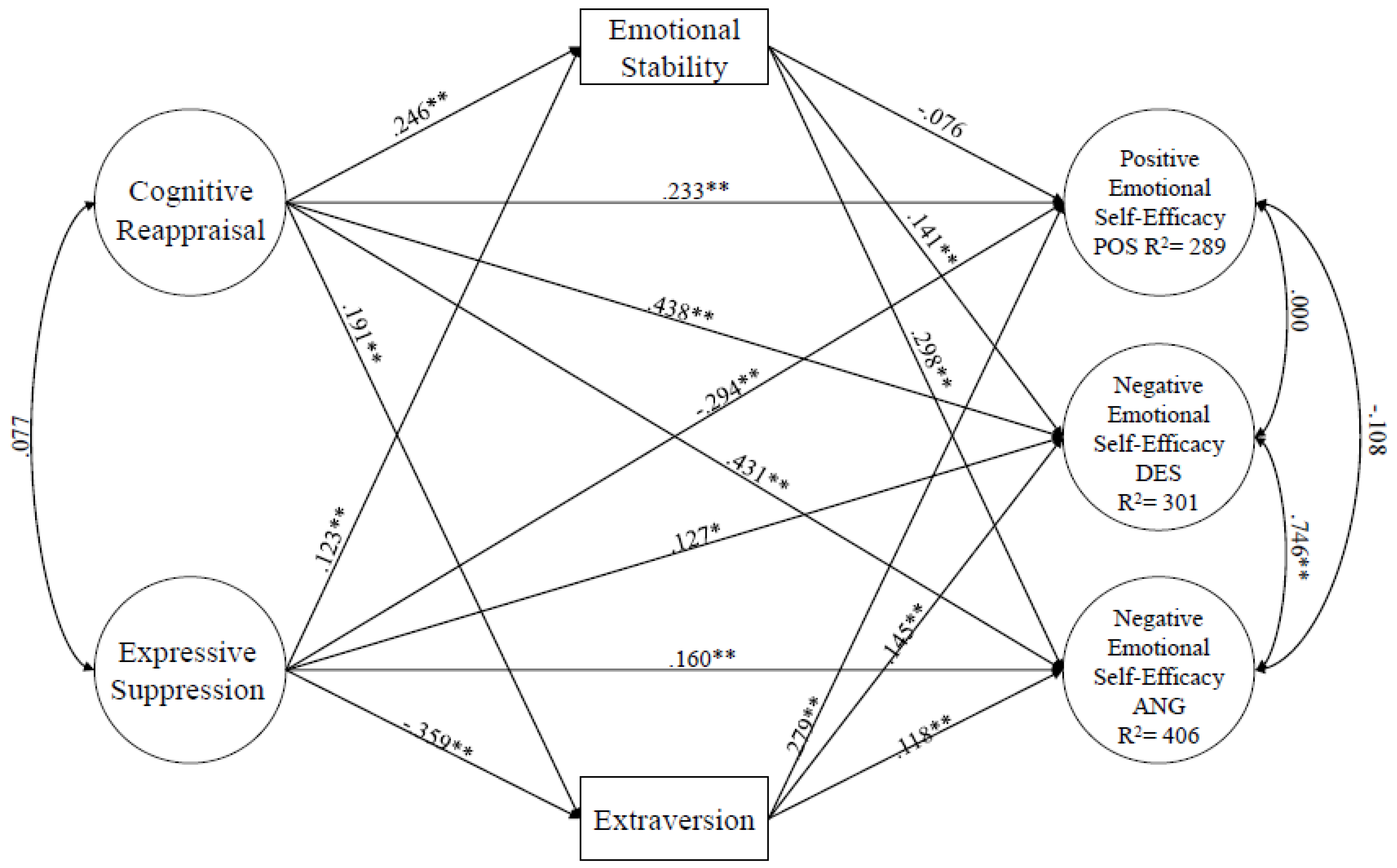

4.2. Structural equation model

5. Discussion and conclusion

5. Limitations and future research

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Caprara GV, Di Giunta L, Eisenberg N, Gerbino M, Pastorelli C, Tramontano C. Assessing regulatory emotional self-efficacy in three countries. Psychol Assess 2008, 20, 227–237. [CrossRef]

- Thompson RA. Doing it with feeling: The emotion in early socioemotional development. Emot Rev 2015, 7, 121–125. [CrossRef]

- Gross JJ. Emotion regulation: Conceptual and empirical foundations. In: Gross JJ., editor. Handbook of Emotion Regulation. London, England: Guilford Press; 2014, p. 3–20.

- John OP Eng J. Three Conceptualizations approaches to individual differences in affect regulation: measures, and findings. In: Gross JJ, editor. Handbook of Emotion Regulation. London, England: Guilford Press; 2014, p. 321–345.

- Preece D, Becerra R, Allan A, Robinson K, Dandy J. Establishing the theoretical components of alexithymia via factor analysis: Introduction and validation of the attention-appraisal model of alexithymia. Pers Individ Dif 2017, 119: 341-352. [CrossRef]

- Verduyn P, Brans K. The relationship between extraversion, neuroticism and aspects of trait affect. Pers Individ Dif 2012, 52(6): 664–669. [CrossRef]

- Bandura A. Growing primacy of human agency in adaptation and change in the electronic era. Eur Psychol 2002, 7: 2-16. [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. On deconstructing commentaries regarding alternative theories of self-regulation. J. Manage 2015, 41, 1025–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeYoung, CG. Cybernetic Big Five Theory. J Res Pers 2015, 56, 33–58. [CrossRef]

- Canals J, Vigil-Colet A, Chico E, Martí-Henneberg C. Personality changes during adolescence: The role of gender and pubertal development. Pers Individ Dif 2005, 39(1): 179–188. [CrossRef]

- Göllner R, Roberts BW, Damian, RI, Lüdtke O, Jonkmann K, Trautwein U. Whose "storm and stress" is it? Parent and child reports of personality development in the transition to early adolescence. J Pers 2017, 85(3): 376–387. [CrossRef]

- Luan Z, Hutteman R, Denissen JJA, Asendorpf JB, van Aken, MAG. Do you see my growth? Two longitudinal studies on personality development from childhood to young adulthood from multiple perspectives. J Res Pers 2017, 67: 44–60. [CrossRef]

- Soto CJ, John OP, Gosling SD, Potter J. Age differences in personality traits from 10 to 65: Big Five domains and facets in a large cross-sectional sample. J Pers Soc Psychol 2011, 100(2): 330–348. [CrossRef]

- Van den Akker AL, Briley DA, Grotzinger AD, Tackett JL, Tucker-Drob EM, Harden KP. Adolescent Big Five personality and pubertal development: Pubertal hormone concentrations and self-reported pubertal status. Dev Psychol 2021, (1): 60–72. [CrossRef]

- Kawamoto T, Endo T. Personality change in adolescence: Results from a Japanese sample. J Res Pers 2015, 57: 32–42. [CrossRef]

- Kawamoto T, Endo T. Sources of variances in personality change during adolescence. Pers Individ Dif 2019, 141: 182–187. [CrossRef]

- McCrae RR, Sutin AR. A five-factor theory perspective on causal analysis. Eur J Pers 2018, 32, 151–166. [CrossRef]

- Matthews, G. Cognitive-adaptive trait theory: A shift in perspective on personality. J Pers 2018, 86, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsh HW, Trautwein U, Luedtke O, Koeller O, Baumert J. Integration of multidimensional self-concept and core personality construct: Construct validation and relations to wellbeing and achievement. J Pers 2006, 74: 403–456. [CrossRef]

- Rogers AP, Barber LK. Workplace intrusions and employee strain: the interactive effects of extraversion and emotional stability. Anxiety Stress Coping 2019, 32, 312–328. [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Zheng Y. Neuroticism and extraversion are differentially related to between-and within-person variation of daily negative emotion and physical symptoms. Pers Individ Dif 2019, 141: 138-142. [CrossRef]

- Soto CJ. Is happiness good for your personality? Concurrent and prospective relations of the big five with subjective well-being. J Pers 2015, 83, 45–55. [CrossRef]

- Kim H, Schimmack U, Oishi S, Tsutsui Y. Extraversion and life satisfaction: A cross-ultural examination of student and nationally representative samples. J Pers 2018, 86, 604–618. [CrossRef]

- Lianos PG. Parenting and social competence in school: The role of preadolescents' personality traits. J Adolesc 2015, 41, 109–120. [CrossRef]

- Bunnett ER. Gender Differences in Perceived Traits of Men and Women. In: Di Fabio A Saklofske DH Stough C CBNC, editor. The Wiley Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences: Personality Processes and Individual Differences. Milton, QLD, Australia: John Wiley & Sons; 2020, pp. 179–84.

- Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annu Rev Psychol 2001, 52, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Toward a psychology of human agency: Pathways and reflections. Perspect Psychol Sci 2018, 13, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura A, Caprara GV, Barbaranelli C, Gerbino M, Pastorelli, C. Role of affective self-regulatory efficacy in diverse spheres of psychosocial functioning. Child Dev 2003, 74, 769–782. [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. On the functional properties of perceived self-efficacy revisited. J. Manage 2012, 38, 9–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barańczuk U. The five factor model of personality and emotion regulation: A meta-analysis. Pers Individ Dif 2019, 139: 217-227. [CrossRef]

- Hoyle RH GP. The interplay of personality and self-regulation. In: Mikulincer ME, Shaver PR, Cooper M, Larsen RJ., editor. APA Handbooks in Psychology APA Handbook of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol 4 Personality Processes and Individual Differences [Internet]. Washington, D.C., DC: American Psychological Association, 2015, pp. 189–207. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/14343-009. [CrossRef]

- Pocnet C, Dupuis M, Congard A, & Jopp D. Personality and its links to quality of life: Mediating effects of emotion regulation and self-efficacy beliefs. Motiv Emot 2017, 41, 196–208. [CrossRef]

- McRae K, Gross JJ. Emotion regulation. Emotion 2020, 20, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Gross JJ. The extended process model of emotion regulation: Elaborations, applications, and future directions. Psychol Inq 2015, 26, 130–137. [CrossRef]

- Gross JJ, John OP. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol 2003, 85, 348–362. [CrossRef]

- English T, John OP, Srivastava S, Gross JJ. Emotion regulation and peer-rated social functioning: A 4-year longitudinal study. J Res Pers 2012, 46, 780–784. [CrossRef]

- Cabello R, Salguero JM, Fernández-Berrocal P, Gross JJ. A Spanish adaptation of the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire. Eur J Psychol Assess 2013, 29, 234–240. [CrossRef]

- Preece DA, Becerra R, Robinson K, Gross JJ. The Emotion Regulation Questionnaire: Psychometric properties in general community samples. J Pers Assess 2020, 102, 348–356. [CrossRef]

- Cameron LD, Overall NC. Suppression and expression as distinct emotion-regulation processes in daily interactions: Longitudinal and meta-analyses. Emotion 2018, 18, 465–480. [CrossRef]

- English T, Eldesouky L. We're not alone: Understanding the social consequences of intrinsic emotion regulation. Emotion 2020, 20, 43–47. [CrossRef]

- Košutić Z, Voncina MM, Dukanac V, Lazarevic M, Dobroslavic IR, Soljaga M, Peulic A, Djuric M, Pesic D, Bradic Z, ve Toševski DL. Attachment and emotional regulation in adolescents with depression. Vojnosanit Pregl 2019, 76, 129–135. [CrossRef]

- Zhang T, Wang Z, Liu G, Shao J. Teachers' caring behavior and problem behaviors in adolescents: The mediating roles of cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression. Pers Individ Dif 2019, 142, 270. [CrossRef]

- Harrington EM, Trevino SD, López S, Giuliani NR. Emotion regulation in early childhood: Implications for socioemotional and academic components of school readiness. Emotion 2020, 20, 48–53. [CrossRef]

- Brenning K, Soenens B, Van Petegem S, Vansteenkiste M. Perceived maternal autonomy support and early adolescent emotion regulation: A longitudinal study. Soc Dev 2015, 24, 561–578. [CrossRef]

- Gunzenhauser C, Heikamp T, Gerbino M, Alessandri G, von Suchodoletz A, Di Giunta L, Caprara GV, Trommsdorff G. Self-efficacy in regulating positive and negative emotions: A validation study in Germany. Eur J Psychol Assess 2013, 29, 197–204. [CrossRef]

- Mesurado B, Malonda-Vidal EM, Llorca-Mestre A. Negative emotions and behaviour: The role of regulatory emotional self-efficacy. J Adolesc 2018, 64: 62-71. [CrossRef]

- Zou C, Plaks JE, Peterson JB. Don't get too excited: Assessing individual differences in the down-regulation of positive emotions. J Pers Assess 2019, 101, 73–83. [CrossRef]

- Bujor L, Turliuc MN. The personality structure in the emotion regulation of sadness and anger. Pers Individ Dif 2020, 162: 10. [CrossRef]

- Brans K, Koval P, Verduyn P, Lim YL, Kuppens P. The regulation of negative and positive affect in daily life. Emotion 2013, 13, 926–939. [CrossRef]

- Heiy JE, Cheavens JS. Back to basics: A naturalistic assessment of the experience and regulation of emotion. Emotion 2014, 14: 878–891. [CrossRef]

- Abbasi IS. The role of neuroticism in the maintenance of chronic baseline stress perception and negative affect. Span J Psychol 2016, 19, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Harenski CL, Kim SH, Hamann S. Neuroticism and psychopathy predict brain activation during moral and nonmoral emotion regulation. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci 2009, 9, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Caprara GV, Vecchione M, Barbaranelli C, Alessandri G. Emotional stability and affective self-regulatory efficacy beliefs: Proofs of integration between trait theory and social cognitive theory. Eur J Pers 2013, 27, 145–154. [CrossRef]

- Shi M, Li X, Zhu T, Shi K. The relationship between regulatory emotional self-efficacy, big-five personality and internet events attitude. 2010 IEEE 2nd Symposium on Web Society 2010. IEEE, pp. 61-65. [CrossRef]

- Dauvier B, Pavani JB, Le Vigouroux S, Kop JL, Congard A. The interactive effect of neuroticism and extraversion on the daily variability of affective states. J Res Pers 2019, 78: 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Gosling SD, Rentfrow PJ, Swann WB. A very brief measure of the Big-Five personality domains. J Res Pers 2003, 37(6): 504-528. [CrossRef]

- Laajaj R, Macours K, Hernandez DAP, Arias O, Gosling SD, Potter J, ... Vakis R. Challenges to Capture the Big Five Personality Traits in non-WEIRD Populations. Sci Adv 2019, 5, eaaw5226.

- Myszkowski N, Storme M, Tavani JL. Are reflective models appropriate for very short scales? Proofs of concept of formative models using the Ten-Item Personality Inventory. J Pers 2019, 87, 363–372. [CrossRef]

- Robles-Haydar, C. A., Amar-Amar, J., & Martínez-González, M. B. Validation of the Big Five Questionnaire (BFQ-C), short version, in Colombian adolescents. Salud ment 2022, 45, 29–34. [CrossRef]

- Hair JFJ, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE. Multivariate data analysis. Edinburgh: Pearson Education; 2014.

- Nunes A, Limpo T, Lima CF, Castro SL. Short scales for the assessment of personality traits: development and validation of the portuguese Ten-Item Personality Inventory (TIPI). Front Psychol 2018, 9: 461. [CrossRef]

- Romero E, Villar P, Gómez-Fraguela JA, López-Romero L. Measuring personality traits with ultra-short scales: A study of the Ten Item Personality Inventory (TIPI) in a Spanish sample. Pers Individ Dif, 2012, 53, 289–293. [CrossRef]

- Wu AD, Zumbo BD. Understanding and using mediators and moderators. Soc Indic Res 2008, 87(3): 367-392. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.-P., & Tsingan, L. Extraversion and neuroticism mediate associations between openness, conscientiousness, and agreeableness and affective well-being. J Happiness Stud 2014, 15, 1377–1388. [CrossRef]

- Murray, L. E., & O'Neill, L. Neuroticism and extraversion mediate the relationship between having a sibling with developmental disabilities and anxiety and depression symptoms. J Affect Disord 2019, 243, 232–240. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q., Kanjanarat, P., Wongpakaran, T., Ruengorn, C., Awiphan, R., Nochaiwong, S., ... & Wedding, D. Fear of COVID-19 and Perceived Stress: The Mediating Roles of Neuroticism and Perceived Social Support. Healthcare 2022, 10(5). [CrossRef]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User's Guide (Sixth Edition). Los Angeles, CA 1998.

- Finney SJ, DiStefano C. Non-normal and categorical data in structural equation modeling. Structural equation modeling: A second course 2006; 10(6): 269-314.

- Marsh HW, Hau KT, Wen Z. In Search of Golden Rules: Comment on Hypothesis-Testing Approaches to Setting Cutoff Values for Fit Indexes and Dangers in Overgeneralizing Hu and Bentler's (1999) Findings. Structural Equation Modeling 2004, 11, 320–341. [CrossRef]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York, NY: Guilford Publications, 2015.

- Kenny DA, Kaniskan B, McCoach DB. The performance of RMSEA in models with small degrees of freedom. Sociol Methods Res 2015, 44, 486–507. [CrossRef]

- Credé, M., Harms, P., Niehorster, S., & Gaye-Valentine, A. An evaluation of the consequences of using short measures of the Big Five personality traits. Pers Soc Psychol Rev 2012, 102, 874.

| Mean |

Standard deviation |

Asymmetry | Kurtosis | Minimum | Maximum | |

| Cognitive reappraisal | 4.40 | .986 | -.023 | -.512 | 2.50 | 6.33 |

| Expressive suppression | 3.72 | 1.26 | .020 | -.957 | 1.50 | 6.00 |

| Extraversion | 4.89 | 1.28 | -.129 | -.917 | 2.50 | 7.00 |

| Emotional stability | 4.29 | 1.20 | -.114 | -.743 | 2.00 | 6.50 |

| Positive emotional self-efficacy (POS) | 4.49 | .490 | -.653 | -.821 | 3.50 | 5.00 |

| Negative emotional self-efficacy (DES) * | 3.17 | .716 | .073 | -.901 | 2.00 | 4.50 |

| Negative emotional self-efficacy (ANG) * | 2.85 | .772 | .054 | -.883 | 1.50 | 4.25 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 1. Cognitive reappraisal | - | |||||

| 2. Expressive suppression | .070 | - | ||||

| 3. Extraversion | .141** | -.299** | - | |||

| 4. Emotional stability | .242** | .107** | -.130** | - | ||

| 5. Positive emotional self-efficacy (POS) | .196** | -.297** | .347** | -.061 | - | |

| 6. Negative emotional self-efficacy (DES) | .408** | .103** | .128** | .236** | .109** | - |

| 7. Negative emotional self-efficacy (ANG) | .422** | .145** | .075 | .359** | -.002 | .595** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).