1. Introduction

Trauma is an out-of-the-ordinary occurrence that can cause individual distress and despair. Children may respond to frightening situations with psychological mechanisms that result in immediate, acute, and occasionally chronic disturbances. PTSD, included in the Disorders Induced by Trauma and Stressors, is a syndrome that develops following exposure to a traumatic event that causes intense fear and feelings of hopelessness, abandonment, or terror [

1,

2,

3]. However, not everyone who encounters such a circumstance develops PTSD. PTSD is essentially a disorder with multiple clusters of symptoms. Traumatic memories, hyperarousal, and a negative disposition characterize it. It is common for PTSD to coexist with melancholy or anxiety disorders [

4]. Rapid transformations and extreme unpredictability characterize the modern era. Therefore, children and adolescents are frequently exposed to highly stressful, even traumatic situations that test their coping abilities. These situations may include natural or human disasters, victimization, violence, or accidents. These traumatic experiences affect children and adolescents physically, mentally, and emotionally and profoundly affect their development, personality formation, and the character and trajectory of their future lives [

5,

6]. After experiencing a traumatic event, the child or adolescent must receive assistance from a mental health professional and support from their environment to mitigate the trauma’s effects as much as possible. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT), which includes a comprehensive set of methods with trauma-focused CBT as its primary representative, is one of the therapeutic interventions that can be used. There are also Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR), exposure therapy, play therapy, and various other methods and approaches that will be described below. The scope of this review is to examine post-traumatic stress disorder in infants and adolescents and treatment options. Differentiating children from adults in psychopathology is a relatively new phenomenon [

7,

8].

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a debilitating mental health condition that can affect traumatized children and adolescents. Among its symptoms are intrusive thoughts, nightmares, avoidance behaviors, and hyperarousal. The advancement of psychotherapeutic interventions plays a crucial role in addressing the symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and facilitating the process of recovery among individuals affected by this condition. These interventions include cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), psychotherapy, and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR). CBT is one of the most extensively researched and effective treatments for PTSD in children and adolescents. It involves identifying and challenging negative thoughts and beliefs associated with the traumatic event, as well as teaching coping skills to manage distressing symptoms. It has been demonstrated that CBT is effective in reducing PTSD symptoms in a variety of populations, including refugee children, those exposed to community violence, and those who have experienced single-incident traumatic events. Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) is another commonly used psychotherapeutic intervention for PTSD.

EMDR combines elements of exposure therapy and cognitive restructuring with bilateral stimulation, such as eye movements or tapping, to help individuals process traumatic memories and reduce distressing symptoms. EMDR has been found to be effective in reducing PTSD symptoms in children and adolescents, and it is advantageous for those who struggle to verbalize their traumatic experiences [

9]. Other psychotherapeutic interventions have shown promise in the treatment of PTSD in children and adolescents, in addition to CBT and EMDR. Trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy (TF-CBT) is a form of CBT that employs trauma-focused interventions, such as exposure therapy and narrative techniques, to address the effects of trauma on thoughts, emotions, and behaviors [

10]. It has been determined that TF-CBT is effective in reducing PTSD symptoms and enhancing overall functioning in this population. When providing psychotherapeutic interventions for PTSD, it is crucial to take into account the unique experiences and requirements of children and adolescents. Age, stage of development, and cultural background can impact the efficacy of treatment approaches. For instance, art-based interventions and group therapy have proven effective in reducing PTSD symptoms in refugee children and adolescents, particularly when language barriers are present. These interventions offer nonverbal means of expressing and digesting traumatic experiences, which can be especially beneficial for individuals who struggle with verbal expression. Despite the availability of evidence-based psychotherapeutic interventions for the treatment of PTSD in children and adolescents, there are still obstacles to their effective implementation [

11]. Therapist characteristics, such as clinical experience and theoretical background, can influence treatment outcomes.

In order to ensure the deliverance of effective interventions, it is also necessary to consider issues pertaining to therapeutic adherence and competence [

12]. In addition, it is important to consider the effect of family factors, such as parental support and family conflict, on the development and perpetuation of PTSD symptoms in children and adolescents [

13]. Psychotherapeutic interventions are essential for the treatment of PTSD in infants and adolescents. CBT, EMDR, and TF-CBT are proven effective interventions for reducing PTSD symptoms and enhancing overall functioning in this population. Art-based interventions and other culturally sensitive approaches should be considered to address the unique requirements of individuals from diverse backgrounds. However, additional research is required to investigate the influence of therapist traits, family factors, and treatment adherence on treatment outcomes. By understanding the efficacy and limitations of psychotherapeutic interventions, clinicians can provide children and adolescents with PTSD with appropriate and individualized care.

2. Literature Review

1980 marked the first official recognition of PTSD as a distinct diagnostic category in the DSM-III. However, scientists at the time believed it only affected adults, not children and adolescents. The informal reference to the disorder dates back much further; for instance, in 1920, Freud defined

traumatic experience as “an experience that causes such a significant increase in arousal in the individual’s mental world that processing by ordinary means fails, resulting in long-lasting disturbances at the level of energy functioning.” During her time in London, Anna Freud treated children who displayed psychological symptoms after the German bombing of the city and children who had escaped from German concentration camps. At that time, the symptoms exhibited by the children were not thoroughly investigated because it was believed that anxious mothers gave birth to anxious children. Winnicott conducted a study in 1971 that demonstrated that trauma significantly impacts children because it destroys their perception that their parents are their protectors, as their parents failed to protect them from the stigmatizing traumatic event. According to research [

14,

15] research on kidnapped and held hostage children indicated that these age groups could also develop PTSD following a traumatic event. Although the road to officially recognizing the disorder as a disorder of childhood and adolescence was long, it became apparent during the 1987 revision of the DSM’s third edition that all age groups are susceptible to it. This finding necessitated a focus on the manifestation of PTSD symptoms in children and adolescents, as it is evident that they utilize psychological and cognitive mechanisms distinct from those of adults. The belief that a child’s response to traumatic events is a temporary adaptation has been replaced by the notion that trauma has long-lasting and severe developmental consequences [

16]. Today, we know that PTSD manifests differently across age groups and requires different treatments.

PTSD is caused by a traumatic event not typical of the human experience. Trauma is derived from the ancient Greek titrosko, which means to hurt. The medical definition of trauma is the “rapid or violent disruption of the continuity of the skin’s tissues, typically resulting in bleeding.” When the pressure exceeds the physiological tolerance limits of the body, physical damage occurs. When we experience an extremely stressful event on a mental level, our inner psychic powers are mobilized to process it as efficiently as possible. If this procedure fails, internal cracks are produced. A psycho-traumatic event is any event that endangers a person’s life and causes severe psychological consequences and adjustment problems, even in those with no history of psychopathology.

2.1. Clinical Signs and Symptoms of Trauma in Children and Adolescents

After experiencing a psycho-traumatic event, children and adolescents exhibit a range of responses. Oftentimes, the symptoms of PTSD do not appear immediately after a traumatic event, i.e., we can have delayed onset PTSD, in which the symptoms appear months or even years after the trauma [

17,

18]. The primary reactions are avoidance of reliving the trauma and increased excitability. Numerous individuals have unwelcomed and uninvited thoughts about the event. Random stimuli (e.g., some sound) can induce reliving. However, it is not uncommon for images to enter a child’s consciousness during quiet times, such as before bedtime, causing sleep disturbances. Increased excitability frequently manifests as irritability, concentration difficulties, insomnia, disturbed sleep, or hypervigilance. A child or adolescent’s school performance may be negatively impacted by elevated arousal and memory and concentration difficulties [

6].

Age and, to a lesser extent, gender are significant predictors of trauma reactions. According to [

16], the random nature of traumatic situations produces despair. It is not uncommon to experience generalized anxiety and obsessions. Younger children become more aggressive and destructive; they may also engage in more repetitive play or drawing with traumatic event-related content and behavioral representations. Young children who have been exposed to persistent stress may develop behavioral issues or an attachment disorder. Regression is a prevalent symptom among younger children, in which the child reverts to earlier developmental stages, such as bedwetting or a sudden loss of verbal skills [

19,

20]. When adolescents are older than 8 to 10 years, their responses begin to resemble those of adults. Children of school age are able to comprehend and make sense of a situation; they can, to some extent, comprehend the long-term effects of trauma and make assumptions about their role in it. In adolescence, there is a stronger focus on the trauma’s long-term effects. In addition, a great deal of emphasis is placed on its social repercussions [

14].

Adults react to trauma with dread, horror, or despair, whereas children may display disorganized and disturbed behavior. Avoidance behaviors are also more difficult to observe in children because they are frequently not cognitively aware of their presence. Loss of interest is another difficult-to-observe behavioral parameter in children, as it typically manifests as listless play, daydreaming, or increased use of imaginary play. Physical distress is common among children and adolescents who have experienced a traumatic event [

16]. In addition to age-based differences, gender-based differences emerge as a growing number of females are diagnosed with PTSD [

14].

Regarding children specifically (6-12 years old): According to previous research, school-aged children do not typically experience visual “flashbacks” or amnesia in relation to the traumatic event. However, they appear to have a disturbed sense of time (time asymmetry); that is, they cannot recall the correct temporal order of events related to the trauma, or “omen generation,” the belief that there were omens that foretold the traumatic event. This perception causes them to be in a constant state of vigilance. The aforementioned symptoms are uncommon in adults [

16]. Children appear less emotionally detached than adults, according to [

6,

14]. This age group makes extensive use of “post-traumatic play,” a recreation of various aspects of the psycho-traumatic event they have experienced. This form of play does not assist the child in reducing negative emotions, as it is more of a traumatic reaction that increases his anxiety and tension levels. They frequently depict the event through drawings, plays, and other verbal and nonverbal means [

21]. Symptoms may manifest both at school and at home. At home, they may manifest as sleep issues, such as nightmares, trouble falling asleep or remaining asleep, sleepwalking, or bedwetting. As the child expects these symptoms to occur outside of bedtime, he or she may be afraid to slumber alone or experience other difficulties. At school, the child may exhibit agitation, hyperactivity, inability to concentrate, or behavioral or academic issues. The aforementioned symptoms closely resemble attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), which frequently results in misdiagnosis [

16].

Specifically with regard to adolescents (12-18): Despite the fact that the clinical picture of adolescents is more analogous to that of adults, there are still differences. Long-term or recurrent exposure to traumatic situations can lead to the development of dissociative symptoms, angry outbursts, self-injurious behaviors, and substance abuse in adolescents. Teenagers are a vulnerable age group with exceptional susceptibility to the negative effects of trauma. The existence of a peer group and the significance of this developmental period can increase risky behavior and the severity of the disorder’s long-term deleterious effects [

16,

17,

21]. Similar to younger children, adolescents are likely to act out aspects of the trauma in their daily lives. This age group is distinguished by the increased impulsivity and aggression that typically follows a traumatic event [

20] they are also more likely than other age groups to “dramatize” the trauma and incorporate it into their daily lives. When they believe they are partially responsible for what occurred, they display “survivor’s guilt” [

16,

19]. The effects of trauma on adolescents are primarily academic and social in nature. In the study [

19] researchers found that adolescents with PTSD are three times more likely to attempt suicide than adolescents without PTSD.

2.2. Diagnostic limitations

The diagnosis of PTSD in children and adolescents is complicated in ways that are absent in the diagnosis of PTSD in adults. Difficulties arise at various stages of the diagnostic procedure, such as when defining a psycho-traumatic event in children and adolescents or anticipating the onset of symptoms. On the one hand, children may exhibit cognitive deficits and limitations in expression or verbalization, which may hinder their comprehension of the psycho-traumatic event [

16]. In the case of children, there are frequently difficulties in reporting certain reactions; for instance, they frequently have trouble reporting correct instances of avoidance reactions because they may be too difficult to verbalize or comprehend and require a more complex cognitive introspection [

14]. It is also not uncommon for them to avoid discussing the event out of fear of upsetting their parents or out of concern that they will be rejected or not understood.

On the other hand, it is well known that infants have a vivid imagination, which they use to embellish their accounts of their experiences. There is also a tendency to mistake the actual for the ‘appearance’. A situation may not be particularly violent, threatening, or traumatizing to adults, but it can still cause significant trauma to children, such as when they are disoriented in a crowd of strangers or when they are sexually touched [

16,

19,

20,

21].

2.3. Cognitive-Behavior Therapy

Although many methods for treating PTSD in children and adolescents have been devised recently, most empirical studies concern cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) [

19]. According to a recent meta-analysis by Danzi & Greca (2021), CBT and trauma-focused CBT, which will be discussed further below, are the most prevalent and effective treatments for adolescent PTSD. Research findings regarding the efficacy of therapeutic interventions may vary depending on the characteristics of the children studied. According to the meta-analysis [

21], most included studies did not discover a statistically significant gender effect. There is also the possibility that the results vary by age. According to the same meta-analysis, there is evidence of increasing effectiveness with age, primarily due to children’s maturation of cognitive mechanisms. Ethnicity and primarily belonging to a minority group could also affect the efficacy of PTSD treatment, while the child’s place of domicile is another potential factor that could affect treatment efficacy; however, these factors do not appear to have been adequately researched. According to reports, characteristics of adolescent caregivers influence treatment efficacy; parental involvement and maternal depression appear to be the most influential; however, additional research is required. An extended duration (total number of treatment hours) has also been associated with better outcomes. CBT appears to be an effective treatment for PTSD regardless of the type of trauma [

21].

As its name suggests, CBT is a psychotherapeutic approach combining behavioral and cognitive techniques. Its goal is to modify dysfunctional thoughts and behaviors developed due to trauma. This structured, experiential treatment focuses on developing a collaborative relationship between the clinician and the treated individual [

22]. It is a broad strategy that encompasses numerous treatments that share fundamental characteristics. Trauma-related psychoeducation, which helps manage reactions to events related to the traumatic experience, as well as information about the disorder and treatment, relaxation and stress management techniques, reduction of avoidance behaviors, exposing the client to the trauma in a safe and controlled manner, and altering dysfunctional beliefs that have developed as a result of the trauma, such as “the world is not a safe place”, are the most prominent commonalities. CBT employs behavioral and cognitive strategies such as gradual exposure, cognitive restructuring, behavioral changes, and the development of social skills and problem-solving techniques to create new, more functional patterns of thoughts, emotions, and behaviors in the child [

19].

CBT is organized into a specific number of structured sessions (usually 4-16) and includes “homework” assigned by the therapist between sessions, intending to help the child or adolescent generalize the skills acquired in therapy to his ordinary life (Theodore, 2017). Individual or group CBT (Group CBT) can be administered [

23]. According to research, CBT is not only one of the most effective treatments for PTSD in children and adolescents, but it is also one of the safest. This conclusion is supported by numerous empirical investigations [

22]. It is considered beneficial for parents to participate in psychoeducation to acquire the skills necessary to manage their children’s symptoms and provide a secure, nurturing environment.

CBT can also take the form of an intervention program implemented in schools. School psychologists can effectively assist students in improving their social-emotional well-being and academic performance, regardless of whether they are affected as individuals or as a school. According to research, one of these intervention programs, Cognitive-Behavioral Intervention for Trauma in Schools (CBITS), is deemed adequate. The weekly group intervention program consists of ten one-hour group sessions, one to three individual sessions, two-parent group training sessions, and a seminar for teacher training. In this program, a mental health professional conducts groups of six to eight individuals. Children acquire new skills in each session through instruction, activities, and individual assignments. The objective is early recognition and intervention to mitigate the disorder’s effects and teach children to handle prospective crises more effectively [

24,

25].

2.4. Trauma-Focused Therapy (TF-CBT)

Trauma-focused CBT is one of the most well-known and frequently employed forms of CBT. It is the most common treatment for PTSD in toddlers and adolescents. It was originally designed to aid victims of sexual abuse, but it has since been adapted for other types of traumatic events. According to multiple studies, trauma-focused CBT is more effective than other treatments for PTSD [

19]. Approving changes that occur following treatment conclusion appear to be long-lasting. However, additional longitudinal research is required to derive this conclusion confidently. In addition to its efficacy, trauma-focused CBT accomplishes cognitive change more quickly than other methods, such as exposure therapy [

26,

27].

When a person undergoes a traumatic event, he obtains “post-traumatic cognitions” that threaten his self and world evaluations. The individual views the world as dangerous and continually feels threatened. This perception of danger can result in several maladaptive responses. Therefore, trauma-focused CBT intends the individual to reexamine the traumatic experience and replace maladaptive thoughts and behaviors with more functional ones [

26].

Trauma-focused CBT is a structured, brief treatment model that combines trauma-focused techniques with cognitive, behavioral, interpersonal, and family therapy principles. It consists of three parts: stabilization and skill development, exposure and cognitive processing of the trauma, and integration of knowledge and treatment completion. The duration of trauma-focused CBT is approximately 12 to 18 weekly sessions. The program introduces the child to skills he will progressively acquire during treatment. The acronym PRACTICE represents the ten essential components of trauma-focused CBT. Before learning to specifically deal with their trauma, the child or adolescent acquires the skills and strategies necessary to recognize and manage various emotions. When practicable, parents’ involvement is significant and a crucial component of this type of treatment, as it is believed to aid in the long-term maintenance of treatment results and the creation of a safe, positive environment for the child. Due to the importance of familial involvement, the therapy includes meetings with the parents and sessions with the child [

16].

Psychoeducation is the primary element of treatment that comes first. Psychoeducation provides people with PTSD with valuable information about trauma and its effects and generally educates them. It is designed to dispel any misunderstandings or false beliefs children or parents may have. The second component consists of parenting techniques typically covered in the initial sessions. Essential skills are praise, selective attention, time-out procedures, and reinforcement programs for decreasing undesirable and increasing desired behaviors. The third component is rest and leisure. Relaxation techniques help the child perceive and control his body’s reactions. Deep respiration and muscle relaxation are the two primary techniques used. The mental health specialist instructs the child on implementing these techniques during sessions.

In contrast, during parental involvement, the child teaches the parents newly acquired skills, aiding their further development. The fourth element of trauma-focused therapy is emotional regulation. Children learn to identify and communicate their emotions. This can be accomplished via games, role-playing, and painting [

28]. Initially, the therapist and the child create a list of the emotions he already recognizes, and then, through the therapist’s hypothetical scenarios, a few more are identified. During the discussion of emotions, a correlation is also made with the accompanying physical sensations. Cognitive coping strategies are the fifth factor. These techniques, which are part of cognitive theory, assist in altering dysfunctional beliefs based on the notion that our thoughts influence our emotions and, consequently, our behavior. Clients practice these through the therapist’s hypothetical circumstances [

16].

The following technique is the trauma narrative, which consists primarily of a progressive and increasing recounting of the child’s traumatic experience and subsequent events [

28,

29]. Although there are numerous ways to accomplish this (photographs, poems, etc.), the most common method is to create a book featuring the client as the protagonist. Cognitive strategies and processing are the seventh component of trauma-focused CBT. After completing the narrative, the therapist begins incorporating cognitive strategies so that the child can revise dysfunctional thoughts associated with the traumatic experience. This can be accomplished through Socratic inquiries, which examine the veracity of the child’s or parents’ negative beliefs. Exposure “In Vivo” to reminders of the trauma is the eighth essential component of therapy. Typically, the child avoids exposure to trauma-related elements gradually and securely. The collaborative sessions with the parents where the child discusses his trauma are also crucial. First, the child is prepared with the therapist for 15 minutes, followed by the parents alone for 15 minutes, and then there is a meeting with everyone present for 30 minutes. The tenth and final essential element of therapy is establishing future security and growth. At this stage, the objective is to instill a realistic sense of security and increase the child’s preparedness to avoid future victimization or vulnerability [

16,

28,

29,

30].

2.5. Prolonged Exposure Therapy

Since 1982, prolonged exposure therapy has developed as a form of CBT. Prolonged exposure therapy is one of the most researched and extensively utilized treatments for PTSD in adolescents. According to research, protracted exposure therapy is adequate for treating PTSD in children and adolescents [

31] however, according to [

29], it does not appear to be more effective than other treatments. Despite its demonstrated efficacy, researchers [

29] found that 25–45% of patients still satisfy the criteria for PTSD after completing treatment. The evidence suggests prolonged exposure therapy is ineffective for individuals with comorbid disorders such as depression, psychosis, suicidal ideation, etc. Nevertheless, some elements consider the treatment safe even in these instances. Concurrent treatment of the comorbid disorder is believed to increase patient safety [

31].

It attempts to alleviate the disorder’s symptoms through safe exposure to the traumatic event and associated thoughts. The relationship between exposure therapy and emotional processing theory is direct. According to her, fear is a cognitive structure within our memories that processes phobic stimuli. Pathology exists when an objectively non-dangerous stimulus activates a fear structure. Therapy aims to alter the individual’s pathological associations and familiarize them with the phobic stimuli that provoke traumatic reactions. It seeks to eliminate fear so the patient can process his traumatic memories effectively. During treatment, the negative reinforcement of avoiding the stimulus diminishes, and new information is provided to reprocess the trauma. The reduction of pathological responses and familiarity with the phobic stimulus can be generalized to similar stimuli [

29,

30].

Sessions typically last 90 minutes and range between 10 and 15 in number. The sessions incorporate psychoeducational components into the treatment so that patients learn about their symptoms and PTSD in general. It also includes in vivo and imaginal exposure to phobic but safe trauma-related stimuli [

31]. Also included in treatment is breathing retraining, which teaches individuals how to calm their breathing and manage their anxiety and panic.

Significantly different from narrative exposure therapy, which will be discussed next, prolonged exposure therapy concentrates on exposure and processing of the traumatic event. Simultaneously, the latter is an account of the individual’s entire existence, from birth to and including the day of treatment. In contrast to narrative exposure therapy, prolonged exposure therapy encourages using the present tense and concentrates on the client’s “worst” memory [

29].

2.6. Relaxation Techniques

Anxiety and fear are common bodily responses to phobic stimuli. To some extent, these organic reactions are considered normal; however, they are pathological if they occur excessively, too frequently, or without sufficient stimulus. Children and adolescents can learn relaxation techniques to combat these bodily responses. They can also be used as a pastime for younger children. Children can control their anxiety, soften the physical reactions that accompany it, and lessen their tension and rage through relaxation techniques. Relaxation techniques are typically employed in conjunction with other forms of therapy, such as CBT. Some relaxation techniques include diaphragmatic breathing, a steady, rhythmic method of deep breathing that can be used for immediate relaxation. This progressive muscle relaxation technique should not be performed on a child with an injured muscle group. It is a gradual tightening and relaxation of the muscles combined with relaxing breathing; the immediate action relaxation technique is a deep breath with parallel tightening of the muscles, guided visualization, in which the child is encouraged to visualize himself as tranquil and relaxed, etc.

Similarly, there are self-relieving techniques, which, along with relaxation techniques, are beneficial for the child to learn before any mention of his trauma. A relationship of safety and trust facilitates the therapist’s ability to impart these techniques to children. These techniques can be taught individually and, in the classroom. When traumatic memories surface, relaxation, and self-soothing techniques (soft singing, swaying, etc.) are intended to eliminate them. Some general guidelines apply to most relaxation techniques. Specifically, the most significant are:

Perform the exercise daily for 10 to 15 minutes.

Perform the exercise in a calm, distraction-free environment.

Perform the exercise at roughly the same time daily, typically after, before bed, or before meals. In the case of education, approximately ten minutes before class begins.

Perform the exercises on an empty stomach since digestion inhibits profound relaxation.

The infant should be comfortable and relaxed while exercising. It was loosening clothing that may be too snug. They explained to the children that they should be fine with whether they performed the exercise accurately during the activity.

Few studies have examined the effectiveness of relaxation techniques. There has been no investigation into relaxation techniques as the primary treatment modality. This may be because relaxation techniques are a subcategory of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), typically used in conjunction with other forms of treatment rather than as the primary method, at least when treating PTSD.

2.7. Systemic Trauma Therapy

Trauma systems therapy is a clinical and organizational approach (Brown et al., 2013) based on the premise that trauma is a complex process requiring specific therapeutic interventions. Trauma systems therapy strongly emphasizes the child’s social environment and capacity to manage trauma. These internal and external factors are the foundation for comprehending and treating children’s trauma. Bronfenbrenner’s ecological model, which emphasized the significance of the systems in which the infant develops, was a driving force in the evolution of therapy [

32]. Trauma systems therapy conducts a dual evaluation [

33]. It evaluates the child’s capacity to regulate emotions and cope with trauma before evaluating their social environment. The assessment of the child’s ability to regulate focuses on his biological systems and how they relate to his survival reactions.

In contrast, assessing his social environment focuses on the environmental and social conditions in which the child develops, which the child may perceive as dangerous even after the trauma has ceased to be threatening. What is essential in PTSD is that the child’s emotional, cognitive, and behavioral responses to stimuli result from incorrectly perceiving them as threatening. These reactions, known as the survival stage, are not random but rather the result of threatening environmental stimuli the infant perceives. Based on these responses and the context in which they occur, we can determine which areas each child requires assistance and which therapeutic stage they should enter. This process assists clinicians in comprehending the complexity of childhood trauma and focusing on the child’s unique problems and requirements [

33].

Effective systemic treatment integrates multiple systems and services, including trauma-focused psychotherapy, legal advocacy, home care, and psychopharmacology. Consequently, a solitary mental health specialist cannot provide systems therapy, but a team of scientists works together. The family also plays a crucial role in this treatment, as their participation is required to establish an appropriate environment for the child. The stages of the treatment are sequential, beginning with the evaluation phase, during which children and their guardians provide the necessary information. In addition to asking about the past, we inquire about the subjectively most severe difficulties and what causes the most “pain” for the people. The treatment strategy is then organized based on the information gathered during the previous phase. It is essential to determine what therapeutic phase the child is in, i.e., whether we should focus on the child’s safety (when his reactions are dangerous or the environment is unstable), regulate his reactions, or help the child move on with life following the trauma. This phase also focuses on the problems that are deemed to be of greater significance. The next phase is commitment, during which the child and his parents concur on a treatment plan. In the final phase of treatment implementation, objectives and procedures vary based on the therapeutic phase the child has been determined to be in [

32].

The goal of therapy focusing on safety is to create a secure environment for the child and reduce their dangerous responses. This is accomplished by educating the child and their caretaker; however, in this approach, legal defense is sometimes required to provide the child with a secure environment. The goal of regulation-focused therapy is to educate children on how to regulate their emotions. This is accomplished primarily through psychoeducation. The primary objective of trauma-focused therapy is to assist the child and their family in moving forward with their lives and altering dysfunctional beliefs that the trauma may have engendered. We must not neglect the specific adjustments that must be made to treatment based on the child’s and family’s culture or background [

32,

33].

Researchers [

34] found that systems therapy reduces PTSD symptoms in children and adolescents while demonstrating clinical and economic effectiveness and high treatment retention rates.

2.8. Play Therapy

Play therapy is an empirically supported form of therapy that can be used as a primary form of therapy or as a supplement to another form of therapy. Using expressive media and materials (art supplies, puppets, etc.), this form of therapy helps children cope with their problems. Due to their limited verbal skills, young children have difficulty expressing complex thoughts and emotions at a young age [

35]. Play therapy provides children with non-verbal means of expression to bridge the divide between abstract thought and limited verbal skills. A positive aspect of play therapy is that it can be adapted to the child’s culture and developmental requirements. Considering that upbringing, education, and influences (such as the expectations of significant others) vary across cultures, the potential multicultural impact of therapy is significant. Despite cultural differences, nearly all cultures use play to teach children life skills; one could even say that play is the universal language for children [

36]. Child-centered play therapy (CCPT) can also benefit children not equipped to deal with their symptoms directly.

The most common and well-known form of play therapy is child-centered play therapy (CCPT), which provides a creative and secure environment for children to work through various difficulties and issues through the creative and personal medium of play. CCPT is an innovative extension of Rogerian client-centered therapy; it is founded on a humanistic orientation that emphasizes the importance of unconditional positive regard, empathy, authenticity, respect, and a positive therapeutic relationship [

36]. For children, the therapist-child relationship is a crucial therapeutic factor [

37]. According to this theory, all individuals can be guided along a positive path if an environment is conducive to growth. Therefore, the therapist must cultivate an environment where the child feels secure and confident and can freely express his thoughts, emotions, and experiences. The primary techniques are observation, reflective listening, emotional contemplation, encouragement, and boundary setting. Through the symbolic action of feelings, thoughts, and experiences that children cannot verbalize, CCPT seeks to improve communication [

36].

Play therapy typically occurs in specially designed rooms with toys meticulously selected to match the child’s developmental stage. Music, dance, humor, narrative, etc., can be utilized during play therapy. For instance, storytelling can aid the therapist in comprehending the child’s perspective or culture. Additionally, it can help children develop a healthy sense of self and express more profound thoughts, memories, and emotions [

37]. Humor can assist in enhancing the therapeutic relationship. Children and adolescents can use music, art, and dance to contend with negative emotions, such as feelings of loss. The therapist can provide clients with suitable art supplies, such as books, so children can explore new creative avenues to express, comprehend, and manage their emotions [

36].

According to research, CCPT is an effective treatment for PTSD in youth. Specifically, most studies conclude that it is statistically significantly preferable to no treatment. It improves treatment outcomes by involving the child’s guardians or caregivers [

35].

2.9. EMDR Therapy

Francine Shapiro, an American psychologist, developed the method of eye movement desensitization and readaptation (EMDR, abbreviated EMDR for brevity) roughly 30 years ago [

38]. It is a treatment based on empirical evidence that was initially designed for adults, but appears to be effective and appropriate for use with children and adolescents. Specifically, for adults, EMDR therapy has grade A status, meaning that the empirical evidence supporting it is based on randomized and controlled studies; for children and adolescents, the treatment has grade B status, meaning that the studies were not randomized and did not involve placebo administration. This is primarily due to the paucity of research concentrating on children, as the emphasis on age differences in disorders is a relatively recent phenomenon [

39]. In this type of therapy, the person’s distressing traumatic experiences are first identified. As they reflect on the traumatic experience they have endured, their eye movements exhibit a rhythmic pattern. The goal is to desensitize the patient and reprocess the trauma in order to eliminate any negative associations [

38].

Shapiro’s adaptive information processing paradigm serves as the foundation for EMDR therapy. The model’s fundamental premise is that mental health or mental disorders are rooted in our memories. Our current perceptions, attitudes, behaviors, and overall experiences are influenced by our memory networks. The data held in these networks affects how we interpret new experiences [

38]. This system can learn from experience and adequately integrate data. Under normal circumstances, experiences are efficiently processed and integrated into certain memory systems. In the case of traumatic experiences, however, the information processing system “freezes,” and the data is not processed adequately. This ineffective integration results in a constant reliving of the trauma, as well as avoidance of trauma-related stimuli and overreaction. Essentially, pathology is the consequence of inadequate information processing. Experiencing a traumatic event is not the only cause of a disorder. Pathology can also be caused by less traumatic experiences, such as “innocent teasing” by peers. EMDR therapy appears to assist the brain in accessing and reprocessing dysfunctionally processed information [

40].

Eye movements may have a positive effect on the phenomenology and physiology of trauma. They can diminish the intensity, emotion, and depth of traumatic memories. They can also positively affect several cognitive processes, including episodic memory and cognitive flexibility. Overall, they can enhance the way individuals experience traumatic memories. Physiologically, they have the ability to decrease heart rate, skin conductance, and respiratory rate, while increasing digit temperature. These physiological alterations can affect how a person perceives a traumatic event. According to research, voluntary eye movements during negative memories reduce their perceived intensity and emotional impact. This occurs as a result of their competitive responses to negative experiences and consumption of system resources.

EMDR is typically administered in eight phases. During the first stage, the clinician documents the client’s history with an emphasis on traumatic events. Determines the treatment’s suitability for the child and attempts to establish a therapeutic relationship based on trust. The second stage (phase of stabilization) entails preparing the individual through proper training. In the third stage, a specific memory target is identified. Individuals are evaluated based on their ability to recognize a negative cognition, i.e., a false or maladaptive self-evaluation, caused by the target memory. It is also valuable for the development of a positively achievable memory-related cognition. The Validity of Cognition (VOC) scale is used to evaluate the validity of cognition. Then, using the Subjective Unit Distress (SUD) scale, he evaluates his degree of distress in light of the negative information. During the fourth stage (phase of desensitization), the emphasis is on the aforementioned material while the individual experiences bilateral stimulation in successive exposures. Keeping all these elements in mind, the individual follows the therapist’s fingers with their gaze for 30 seconds. After taking a breath, the individual is questioned about the procedure that created new material. The next cycle of eye movements will focus on the new information. Multiple instances of alternating exposure with patient feedback are accompanied by cognitive and physiological changes [

40].

In the fifth stage, or cognitive installation phase, connections with positive cognitive networks increase. Through bilateral stimulation (primarily saccadic eye movements induced by the therapist), the individual is asked to match the identified positive belief with the initial traumatic experience. The individual’s self-reported VOC assesses the efficacy of this stage in an effort to increase the VOC score to 6 or 7. The sixth stage is the body scan, in which the subject concentrates on the physical sensations of their body while being exposed to sensory stimuli. The seventh stage is the conclusion of the treatment, which includes an evaluation of the treatment’s efficacy. However, the clinician also teaches the individual self-soothing techniques. In the eighth stage, a reevaluation is performed at the start of every session. Using SUD, VOC, and physical self-exposure measures, the therapist verifies that treatment benefits have been sustained. The eight phases described must be tailored to the requirements of the child and his family, as well as his linguistic and cognitive abilities, on a case-by-case basis. The presence of the parent’s during treatment is contingent upon the child’s desire or need for support, as well as the therapist’s professional judgment. Parents should be adequately trained to assist and support their children.

Several studies, according to [

38,

39,

40], demonstrate that EMDR therapy is an effective treatment for trauma in children and adolescents. In addition, it is considered one of the primary treatments for PTSD. However, its suitability depends on several factors, including the establishment of a therapeutic relationship of safety and trust, the individual’s ability to use relaxation techniques, the absence of additional crises, the presence of a support network, the absence of evidence of eye pain during treatment, the absence of substance or benzodiazepine use, the absence of dissociative identity disorder, organic brain damage, heart disease, epilepsy, or other medical conditions, and the absence of a support network. According to [

40] there is evidence that EMDR therapy is more effective than CBT for infants and adolescents. However, these two forms of therapy appear to be the most effective when compared to other techniques used to treat PTSD.

2.10. Narrative Therapy

Narrative exposure therapy (NET) is a set of narrative techniques that emphasizes each individual’s personal narratives and the subsequent thoughts they develop. Each individual lends meaning to his experiences, but the meaning he ascribes to these experiences ultimately influences the individual and his self-perception. Fundamental to narrative therapies is the notion that “we are the stories we tell.” A mentally sound individual’s narratives are more meaningful, vivid, and logical. PTSD has been linked to the absence of these healthy narrative patterns and the presence of narratives that are more ambiguous and unassimilated. Creating “healthy” narratives is a means of rehabilitating our psyche. During narrative exposure therapy, patients discuss their trauma and recall trauma-related thoughts and emotions. As the narrative unfolds, with the assistance of the therapist, the individual uncovers more functional thoughts and reactions, and ultimately reconstructs how he perceives the traumatic experience he has endured [

41]. Similar to protracted exposure therapy, the treatment is predicated on the notion that an objectively non-threatening stimulus is associated with a phobic response. The objective is therefore to alter this pathological, incorrect association and for the traumatized individual to reprocess the traumatic event [

29].

Narrative exposure therapy is concise, grounded in reality, and intended for use after a crisis. Sessions typically last 90-120 minutes and range from 5 to 10 sessions. Also included in the first workshop is psychoeducation [

29]. As stated previously, it is suited for addressing the problems of refugees. Diverse forms of therapy focus on the “worst” traumatic event in the belief that addressing it will produce the best potential results.

In most instances, it is difficult to identify a single event as the “cause” of the disorder. In exposure therapy, the client creates a narrative of his entire life, not just the alleged traumatic event, in order to surmount this issue. Due to PTSD symptoms, trauma memories and processing are frequently inaccurate [

41]. Therefore, a consistent narrative is necessary.

If the client is a child, the therapist may use role play or visual aides to assist the child in reconstructing the traumatic event. For instance, he can use a cord or rope to symbolize the child’s life and a rock or flowers to represent the trauma, which will be placed on the rope when the traumatic event occurs. Typically, exposure therapy for adolescents consists of eight sessions. Children should have already been diagnosed and have a documented medical history. Psychosis and substance abuse are exclusion criteria for treatment, so it is beneficial to be aware of their presence prior to beginning the procedure [

41]. This method’s short-term nature is a significant advantage, as we observe improvement from the first sessions.

2.11. Psychodynamic Therapy

The history of psychodynamic psychotherapy for children and adolescents is extensive. Its origins lie in Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalytic theory, but its application to children and adolescents is primarily based on the work of Anna Freud and Melanie Klein [

42]. In addition to psychoanalytic concepts, it incorporates elements from other fields, including developmental psychology, neuroscience, and attachment theory [

43]. Although there are a variety of psychoanalytic psychotherapies available today, the terms are frequently used interchangeably. Typically, psychoanalytic psychotherapy refers to a briefer form of treatment in which the therapist focuses on particular problems rather than the entire personality. Nonetheless, there are some common theoretical principles, such as the therapist listening to and observing the client’s behavior. The objective is to resolve internal conflicts, which may be rooted in negative past experiences and cause anxiety or pain. These conflicts are typically pushed into the unconscious by defense mechanisms. However, they can frequently become harmful (e.g., denial, projection, etc.). Defense mechanisms are not always harmful (e.g., use of humor, etc.), but they can frequently become so (e.g., denial, projection, etc.). Through conversation, play (in younger children), and the therapeutic relationship, psychoanalytic psychotherapy attempts to determine how a person’s past experiences influence their current thinking, behavior, and mental state, as well as their relationships with others [

42].

There are records of its use dating back to 1995, with rates of approximately 44 percent of all public care provided. Despite its long history, there were not many empirical studies demonstrating its effectiveness until recently. Researchers [

44] note that psychodynamic psychotherapy focuses primarily on emotion, defense mechanisms and avoidance of thoughts and feelings, the past, behavioral patterns, interpersonal relationships, and the patient’s fantasies and desires. The treatments of this approach are predicated on the theory that difficulties in past relationships or other negative experiences are pushed into the unconscious, only to resurface as problems in the present. Through the relationship with the psychotherapist, the individual attempts to gain conscious comprehension of the unconscious conflicts he experiences in order to recover.

Psychoanalytic psychotherapy necessitates difficult work from the client, can be a painful experience, and things may need to worsen before they improve. A child who has been abused by a family member, for instance, may need to gradually accept the fact that someone they love or admire has abused the power of their position within the family [

42]. Psychoanalytic psychotherapy is typically administered to individuals, but it can also be administered to groups or families. In most cases, the individual treatment is administered at a set time once or twice per week; however, in exceptional circumstances, it may be more intensive. When the patient is a child or adolescent, it is essential that parents or caregivers receive parallel supportive treatment. In some cases, it may be brief and consist of only a few sessions, whereas in others, it may last for months or even years. Priority number one is ensuring the child’s safety, particularly in cases of abuse. The treatment must be tailored to the child’s age and requirements [

42].

There are differing opinions regarding the efficacy of this intervention. Some emphasize the importance of the therapeutic relationship, while others emphasize the insight (conscious understanding) of unconscious conflicts. Free association is a technique in which the client is encouraged to talk about anything that comes to mind while the therapist asks questions. During therapy, therapists do not reveal personal information because it is believed that the client will unconsciously treat them similarly to how they were treated in previous relationships. This process can result in experiencing negative emotions again. The gradual discovery of the patient’s unconscious conflicts and defense mechanisms is facilitated by “transferring” past relationship feelings to the therapist. Understanding the patient’s unconscious conflicts and defenses is necessary for their resolution. For younger children, play, symbolic play, painting, etc., is the fundamental technique.

Play is a “window” through which a therapist can perceive feelings and thoughts that a child is unable to verbalize. As children play, they develop a sense of security, making it easier for them to discuss difficult topics or troubling thoughts. Through play and imagination, they can express their conflicts at a more developed developmental level than they are, which is considered therapeutic [

42]. Child psychodynamic psychotherapy is effective for a variety of childhood disorders, with varying degrees of efficacy across disorders; for instance, results are more favorable for internalizing and affective problems than externalizing problems. In comparison to other forms of therapy, the outcomes of psychodynamic psychotherapy are inconsistent, but it is generally regarded as equally effective. The mechanisms utilized by this approach are distinct from those of other approaches; consequently, its results may be slow to manifest (worsening prior to improvement); however, the improvement appears to persist over time. Despite individual differences that make treatment more effective for some, research indicates that younger children appear to benefit more than their older counterparts. Parental involvement is regarded as a crucial factor for the successful outcome of treatment [

43].

According to researchers [

44], psychodynamic psychotherapy for children and adolescents appears effective and comparable to CBT and systems therapy. The research by researchers [

43] concurs with these findings but adds that individual psychodynamic psychotherapy is more effective than group psychotherapy for traumatized children. Multiple studies concur that this treatment has beneficial effects and reduces PTSD symptoms. In contrast to other forms of treatment, such as CBT, the number of empirical studies on psychodynamic psychotherapy in children remains low [

45].

2.12. Pharmacotherapy

PTSD is a disorder with a dual basis. It influences the psychological mechanisms and numerous biological systems of the individual. Consequently, pharmacological treatment is frequently employed in addition to the aforementioned established psychological remedies. Today, research in the field of pharmacology has advanced significantly, resulting in a variety of highly effective drugs with fewer adverse effects and a lower likelihood of addiction. Medication is intended to reduce the physiological effects of stress on the body, which may have an impact on memory, the perception of terror, etc. We could say that PTSD is the result of a maladaptation to a traumatic event-stressor, which can result in alterations to the individual’s neural networks [

46]. Careful consideration should be given to comorbidity with other disorders, previous disorders or treatments, current medications, and the individual’s medical conditions when selecting medications. Changing the medication is regarded necessary if the anticipated effect does not occur.

Anxiolytic-suppressant medications, such as benzodiazepines, tricyclic antidepressants, and MAO inhibitors, constitute the first line of pharmacological treatment. This category attempts to reduce intrusive memories and avoidance behaviors, as well as reduce stress and improve concentration. In addition to antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are also used to treat PTSD. This class of medication has demonstrated efficacy in reducing the severity of PTSD symptoms and preventing relapse. Inhibitors of selective serotonin reuptake seek to alleviate depression, numbness, hyperarousal, and generalized anxiety. Increasing serotonin levels in the brain has beneficial effects, such as enhancing appetite and sleep. Other types of antidepressants, adrenergic receptor antagonists, anticonvulsants, and atypical antipsychotics may also be employed [

46].

3. Materials and Methods

This paper included English-language articles, studies, meta-analyses, and reviews published between 2016 and 2023. More emphasis is placed on quantitative research that seeks to demonstrate the efficacy of therapeutic interventions used to treat juvenile PTSD and post-analyses to determine which are deemed more effective. The search was conducted to identify the most recent studies with adequate sample size and methodology. Preference was given to empirical and randomized controlled trials.

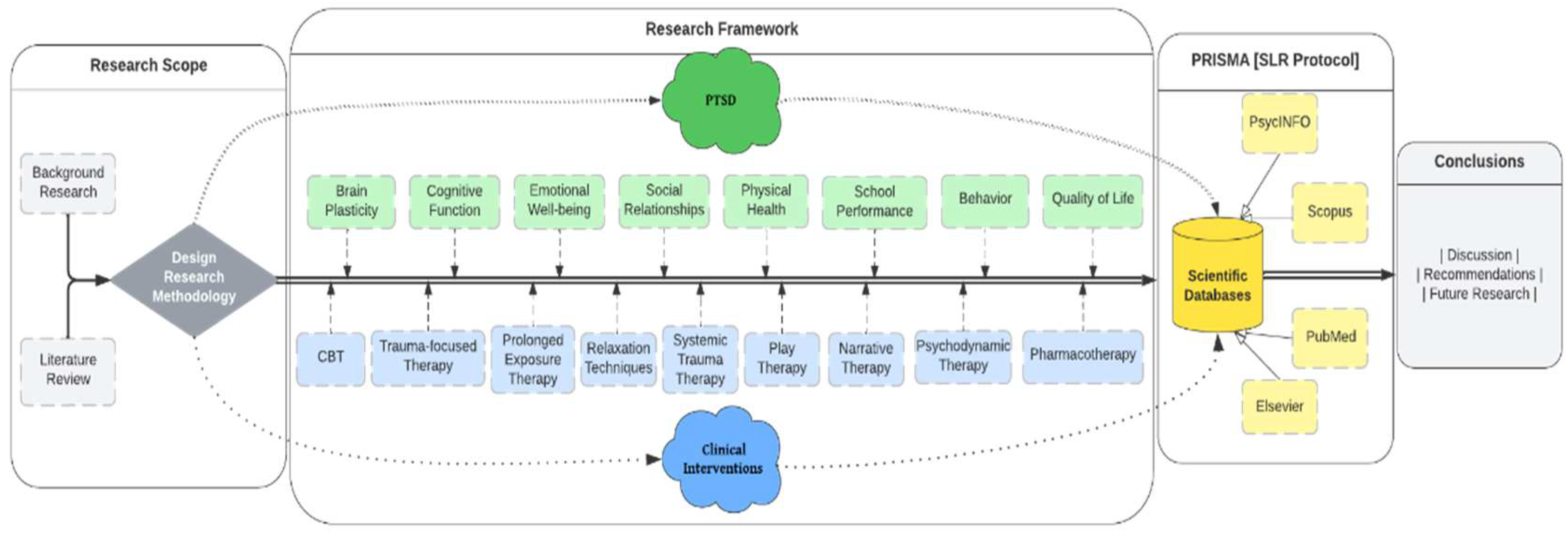

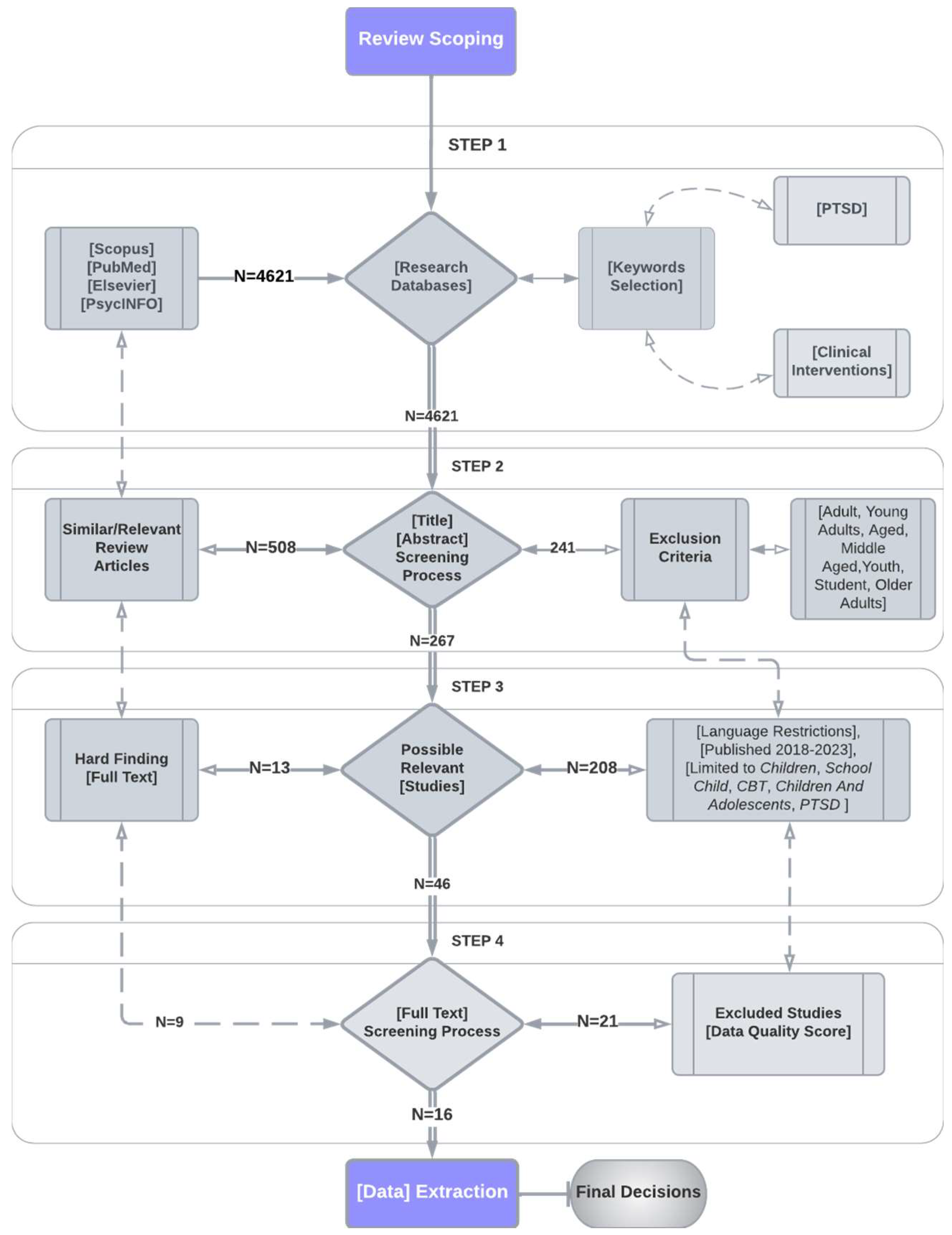

However, their number is negligible as child-adolescent psychopathology is still in infancy. Studies conducted with a sample of adults or small sample size (e.g., case studies) conducted before 2016 were disregarded. The primary focus of this investigation was the efficacy of therapeutic interventions for children and adolescents aged 5 to 17 years old. Using Boolean logic, the PsycINFO, Scopus, PubMed, and Elsevier databases were searched. Children and adolescents with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Clinical Interventions for PTSD in Children and Adolescents, as well as PTSD in children and adolescents, PTSD treatment, and PTSD interventions in English. In addition to the general search with the terms listed above, a separate search was conducted for each intervention, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, systems therapy, trauma system therapy, etc. (

Figure 1).

Initially, the inquiry was conducted using more general criteria. Then, the exclusion of studies that did not meet the defined, stringent, and specific criteria began. The survey date was one of the essential factors that were calculated. The holding date was to be strictly after 2016 only. Also crucial was the age span of the sample, which had to be between 5 and 17. The acceptable deviation from the defined age was two years older or younger. However, most included studies have a sample age range of 5 to 17 years. Priority was given to quantitative research over qualitative research. The logic of the specific research was to gather information about each approach separately initially but also to demonstrate its efficacy by gathering data from previous research and then to compare the methods’ efficacy to determine which is deemed more effective and is typically preferred by mental health professionals to treat youth PTSD (

Figure 2).

The date of the study was later than 2016, the article was published in a reputable journal or by a reputable author, the entire article was available online, the mandatory existence of PTSD symptoms in the subjects of the sample of each study, the sample to have an upper age limit of 18 to 20 years (i.e., not to concern research focusing on adult populations), the interventions used focused on reducing the symptoms of the disorder, and we were the authors of the study. Research that did not comply with the abovementioned requirements or that was not written in Greek or English was automatically excluded. A criterion for exclusion was the presence of a sample that concerned a subset of the population and not the entire population.

From the 4621 bibliographic sources that were initially identified, only 16 were included in this work. All post-analyses included both qualitative and quantitative assessments of the interventions’ efficacy. The clinical sample was evaluated using DSM-5 or ICD-11 criteria for diagnosing post-traumatic stress disorder. In most instances, an interview or questionnaire was administered to the infant or his/her caretaker. In most studies, a PTSD diagnosis was not required for inclusion in the sample, but the presence of PTSD symptoms was. The typical experimental design included one or more experimental groups (depending on the number of interventions in each study) and a control group that did not receive the intervention. Generally, there was no sample preparation before the beginning of the research; however, in many instances, follow-up studies were conducted to determine whether the effects of the interventions were stable over time. Few meta-analyses, systematic reviews, and randomized controlled trials have been conducted to compare the efficacy of interventions for youth PTSD. Due to this, most reviews include the same studies, which may need to be considered when interpreting our findings.

3. Results

Most of the literature on PTSD treatment focuses on CBT, particularly trauma-focused CBT. Numerous studies suggest trauma-focused CBT is the most effective treatment for infant and adolescent PTSD. According to the meta-analysis conducted by Danzi and Greca (2021), trauma-focused CBT is the most effective and well-established treatment intervention for adolescent PTSD. In the meta-analysis conducted by [

47], trauma-focused CBT was identified as the most effective intervention with a large effect size compared to no treatment. This meta-analysis by the researchers concurs with these results who also concluded that trauma-focused CBT is the most effective treatment for childhood and adolescent PTSD. In a study of meta-analysis [

48], EMDR therapy demonstrated significant effects in the uncontrolled analysis but only minor to moderate effects in the controlled studies included. According to study [

49], CBT is the only treatment considered well-established, while all others are considered to be possibly adequate or investigational. Individual trauma-focused CBT is defined as the most effective and well-established method. Group CBT, typically administered in a school setting, was also deemed adequate, whereas group CBT with parental participation and EMDR therapy may be effective. Psychoanalytic psychotherapy and client-centered play therapy were considered experimental.

A study [

49] identifies some commonalities among the approaches they have found to be effective: psychoeducation regarding the prevalence, consequences, and treatment of trauma, training in emotion regulation and problem-solving strategies, imaginal exposure or vivo exposure, and cognitive processing. Due to the limited research on psychopharmacological interventions, mental health professionals should use medication cautiously. Based on [

50] findings, there is an inverse correlation between children’s exposure to medical information and their posttraumatic stress level several months after a medical episode. A significant correlation exists between preschoolers and school-aged children. In addition, six recent meta-analyses and systematic reviews have evaluated psychological treatments for PTSD in children and adolescents, as noted by [

21]. CBT, eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), narrative exposure therapy, and classroom-based interventions were supported. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy (TF-CBT) have emerged as well-established treatments for PTSD in children and adolescents. Support also arose for EMDR, narrative exposure therapy, and school-based interventions, despite a more limited evidence base. In addition, the study [

51] found that every child or adolescent has been exposed to at least one war-traumatic event, which is associated with increased mental health and behavioral issues. This calls for counseling programs that can assist these families and children. The findings of the study [

52] suggest that parental emotional validation and invalidation may be beneficial as treatment goals for clinical intervention with this population. To strengthen the therapist-patient alliance, interventions recommend that therapists utilize emotional validation.

The results of the study [

53] indicated that TF-CBT interventions were more effective than control conditions at reducing PTSD symptoms. In trauma-exposed adolescents, complex traumatic events’ short- and long-term effects may lead to psychiatric diagnoses other than PTSD (such as affective, personality, and psychotic disorders). They may cause dissociative and somatic symptomatology, which may be more disabling than posttraumatic symptoms. The requirement for trauma clinical interventions is to implement individualized and appropriate therapeutic interventions.

In addition, TF-CBT may be especially useful in addressing the psychosocial difficulties of youth at risk for or engaging in familial sex trafficking and labor exploitation. TF-CBT not only reduces the psychosocial difficulties of children who have endured childhood adversity and trauma, but it may also substantially improve these children’s resilience [

54]. According to the study [

55], college students with a history of elevated ADHD symptoms in childhood reported significantly more trauma exposure and PTSD symptoms. These findings have implications for clinical interventions with children and adolescents, college counseling, and accessibility services related to psychological health and academic accommodations. Another study [

56] note that interventions aimed at preventing trauma, PTSD, and depression should be multifaceted and targeted at multiple levels, such as the individual/interpersonal level (reducing abuse in the household and immediate environment) and the community/societal level (reducing crime rates in communities and strengthening conviction policies). In addition, in a study [

57] are presented alternative therapeutic approaches for trauma treatment. The intervention included mindfulness-based practices, expressive arts, and EMDR (Integrative Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing) group therapy.

Table 1.

Main Results and Study Characteristics.

Table 1.

Main Results and Study Characteristics.

| Author (year) |

Type of study |

Sample |

Instrument |

Conclusions – Guide to Clinical Interventions |

| Ben Ari et al. (2019) [50] |

Prospective Study |

Intervention Group N=151 |

Semi-structured interview

CBCL (child behavior checklist)

PTSDSSI (post-traumatic stress disorder semi-structured interview)

PCASS (the preschool children’s assessment of stress scale)

UCLA-PTSD (the University of California at Los Angeles post-traumatic stress disorder) reaction index: DSM-V version

SCARED (the screen for child anxiety related emotional disorders) |

Findings show an inverse correlation between the children’s exposure to medical information and their level of post-traumatic stress several months after their medical episode. The correlation is significant in both preschool children and school-aged children. |

| Danzi & La Greca (2017) [21] |

RCTs and Open Trials, Controlled and uncontrolled studies; follow-up effects |

37 studies primarily focused on PTSD, 20 RCTs that focus primarily on PTSD, 41 RCTs of varied interventions for youth with PTSD, 135 studies (controlled and uncontrolled) on psychological treat-ments for PTSS in youth and found the largest effect sizes for CBT |

Semi-structured interview and questionnaires examining parameters: Gender, Age, Ethnicity, Domicile, Parent/Caregiver Factors, Trauma Types, Treatment Factors

|

Psychological treatments for PTSD in children and adolescents have been evaluated by six recent meta- analyses and systematic reviews. They found support for CBT, eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), narrative exposure therapy, and classroom-based interventions. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy (TF-CBT) clearly emerged as well-established treat-ments for PTSD in youth. Support also emerged for EMDR, narrative exposure therapy, and school-based interventions, although the evidence-base was more limited. |

| El-Khodary et al. (2019) [51] |

Quantitative |

N=1029 children and adolescents 11-17 yrs old |

War-Traumatic Events Checklist (W-TECh), Multicultural

Events Schedule for Adolescents (M.E.S.A.)

Post-traumatic Stress Disorders Symptoms Scale (PTSDSS)

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire

Child Depression Inventory (CDI) |

The results show that every child or adolescent had at least one war-traumatic event, which increased mental health and behavioral issues. Counseling programs for these families and their children are needed. |

| Ferrajão (2020) [52] |

Quantitative |

60 children

(51.7% female and 48.3% male) |

Child PTSD Symptom Scale

Children’s Depression Inventory 2

Emotional Validation Experiences Questionnaire |

Parental emotional validation and invalidation may be useful clinical intervention goals for this population. Therapy interventions recommend emotional validation to improve therapist-patient relationships. |

| Forresi et al. (2019) [58] |

Cross-sectional |

682 children

and adolescents (9–14 years)

1162 parents |

UCLA PTSD-Index

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ)

SCL-90

|

The results emphasize the need for better clinical interventions for children and adolescents exposed to earthquakes. |

| Grainger et al. (2022) [53] |

Systematic Review & Meta-analysis |

40 randomized controlled trials |

PROSPERO

TF-CBT interventions |

The results suggested that TF-CBT interventions performed better than control conditions at reducing PTSD symptoms

|

| Luoni et al. (2018) [59] |

Cross-sectional |

107 subjects, aged between

12 and 18 years |

Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-IV

Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory–Adolescent Version

Trauma Symptom Checklist for Children (form TSCCA)

Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach)

Clinical Global Impressions-Severity of Illness Scale |

Complex trauma can cause short- and long-term psychiatric diagnoses like affective, personality, and psychotic disorders in traumatized adolescents, as well as dissociative and somatic symptoms that may be more debilitating than PTSD. Trauma clinical interventions’ need for individualized therapy. |

| Márquez et al. (2020) [54] |

Qualitative |

Case-Study

Carmen is a 14-year-old Guatemalan female |

Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT)

PRACTICE - Psychoeducation & Parenting skills,

Relaxation, Affective expression and modulation, Cognitive

coping, Trauma narrative & processing In vivo mastery, Conjoint sessions, and Enhancing safety and

future development |

TF-CBT may help youth at risk for or involved in familial sex trafficking and labor exploitation with psychosocial issues. TF-CBT can improve resilience and reduce psychosocial difficulties in children who have experienced childhood trauma and adversity. |

| Miodus et al. (2021) [55] |

Quantitative |

College students - N=454 |

UCLA PTSD Reaction Index, DSM-IV

The Barkley Adult ADHD Rating Scale–IV

Beck Depression Inventory–Second Edition

Beck Anxiety Inventory |

A childhood history of ADHD symptoms was associated with higher trauma exposure and PTSD symptoms in college students. Impacts include clinical interventions for children and adolescents, college counseling, and accessibility services for psychological well-being and academic accommodations. |

| Nöthling et al. (2016) [56] |

Quantitative |

N=215 adolescents |

Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (K-SADS-PL)

Child PTSD Checklist (CPC)

Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ)

Child Exposure to Community Violence Checklist (CECV) |

To effectively prevent trauma, PTSD, and depression, interventions should address multiple levels, including individual/interpersonal (reducing abuse in the home and environment) and community/societal (reducing crime rates and strengthening conviction policies). |

| Roque-Lopez et al. (2021) [57] |

Quantitative |

Forty-four girls (aged 13–16 yrs) |

Adverse childhood experience (ACE)

Short PTSD Rating Interview (SPRINT)

Child PTSD Symptom Scale (CPSS)

Mindful Attention Awareness Scale-Adolescents (MAAS-A) |

The intervention included mindfulness, expressive arts, and EMDR group therapy. The results suggest that this integrative/complementary short-term program may reduce psychological burden in adolescents with multiple adverse childhood experiences. We found improved psychological functioning in adolescents after 2 months, but they may need group or individual follow-up to strengthen the mental health benefits of this intervention. |

| Rudd et al. (2019) [60] |

Quantitative |

N=114 clients |

Child PTSD Symptom Scale

Ohio Mental Health Consumer Outcomes System—Ohio Youth Problem, Functioning, and Satisfaction Scales |

This study is the first benchmarking study of TF-CBT and provides preliminary findings with regard to the effectiveness, and transportability, of TF-CBT to urban community settings that serve youth in poverty. |

| Russotti et al. (2023) [61] |

Quantitative – prospective longitudinal cohort study |

514 racially/ethnically

diverse adolescent females (15–19 years) |

Child maltreatment determined by substantiated caseworker reports

Beck Depression Inventory-II

Comprehensive Trauma Interview

Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment – IPPA

Child’s Report of Parental Behavior Inventory |

The current study applied a person-centered approach to (a) identify subgroups of adolescent females characterized by distinct patterns of attachment quality with peers, fathers, and mothers and (b) determine if the effect of maltreatment on depressive and PTSD symptoms varied as a function of distinct patterns of attachment quality. |

| Sarkadi et al. (2017) [62] |

Qualitative |

N=139 unaccompanied refugee minors (URMs) |

Teaching Recovery Techniques (TRT) – 6 week program |

There were significant differences in depressive and PTSD symptoms between pre- and post-measures, despite 62% of participants experiencing negative life events during the program and being in the asylum process. The qualitative interviews identified six categories: social support, normalization, valuable tools, comprehensibility, manageability, and meaningfulness. The program theory of TRT states that sharing experiences in a safe and supportive environment and learning coping tools like trauma-specific exposure and behavioral activation will increase youth’s sense of coherence and reduce depression and PTSD symptoms. TRT appears to be a promising PTSD prevention strategy for URMs. |

| Shearer et al. (2017) [63] |

Quantitative |

N=29 |

Cost-utility analysis taking the

UK National Health Service/Personal Social Services perspective

for costs and using QALYs as the primary economic outcome. |

The study provides preliminary evidence for the cost-effectiveness of cognitive therapy in this treatment population. The intervention

was delivered by clinical researchers and results may be difficult to replicate in general practice. CT-PTSD was likely to be cost-effective compared to usual care from the NHS/personal social services perspective. |

| van der Spuy et al. (2018) [64] |

Quantitative |

12 traumatized children, aged 5–7 years |

Trauma Symptom Checklist for Young Children (TSCYC) |

The results indicate a significant reduction in all but one of the symptoms of post-traumatic stress Eye Movement Integration (EMI) may be a useful brief therapeutic intervention for young children in resource-constrained settings. |

The results support this intervention as a prospective short-term integrative/complementary program for reducing psychological burden in adolescents with a history of multiple adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). Although we observed an improvement in psychological functioning over a 2-month post-discharge period, the adolescents may still require group or individual follow-up support to enhance and consolidate the mental health benefits of this intervention. In the study [

60], the first benchmarking study of TF-CBT, provide preliminary findings regarding the efficacy and transferability of TF-CBT to urban community settings serving low-income adolescents. In the study by [