Submitted:

10 January 2024

Posted:

11 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients and Inclusion Criteria

2.2. Self-Completion Questionnaire

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

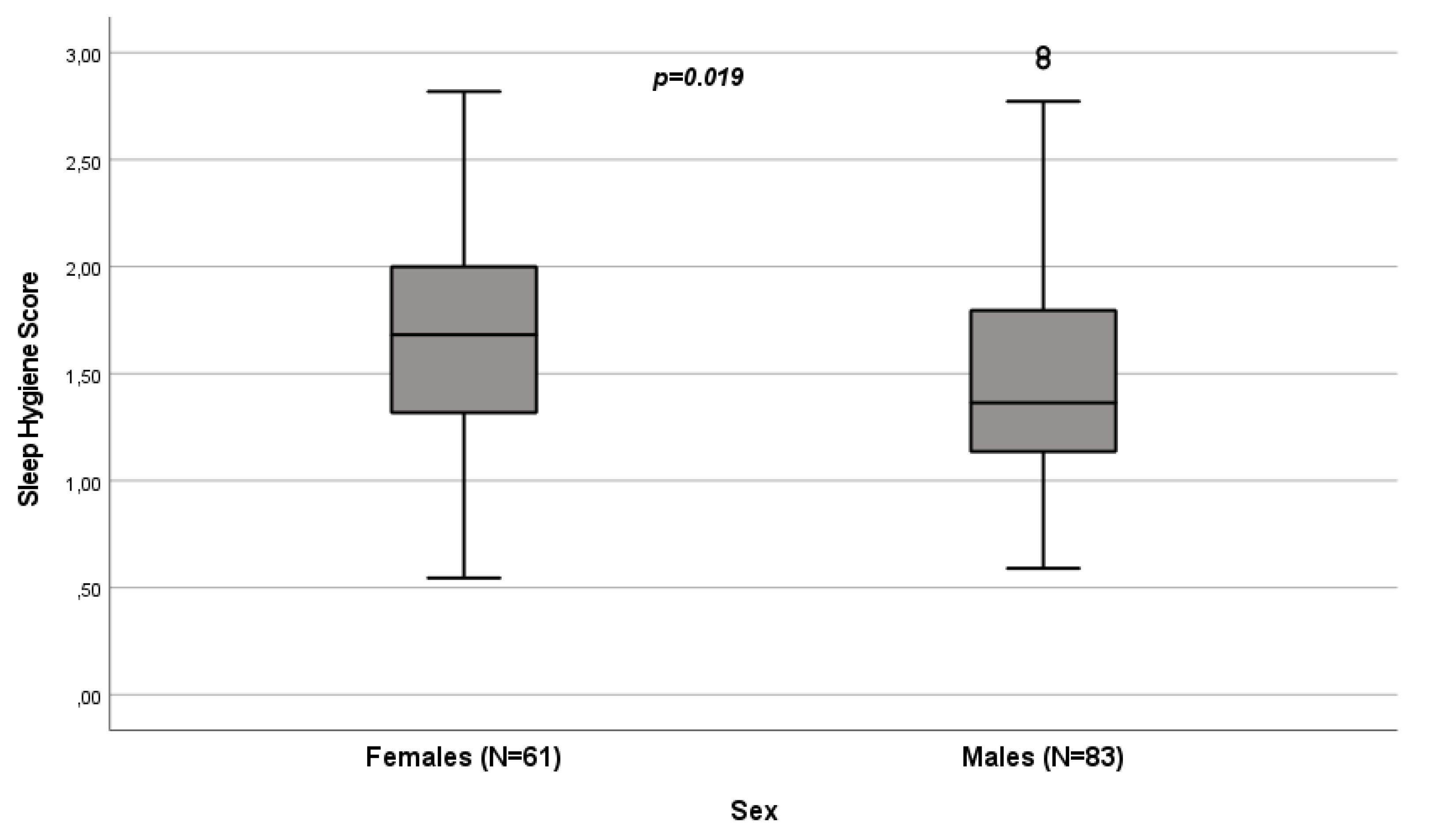

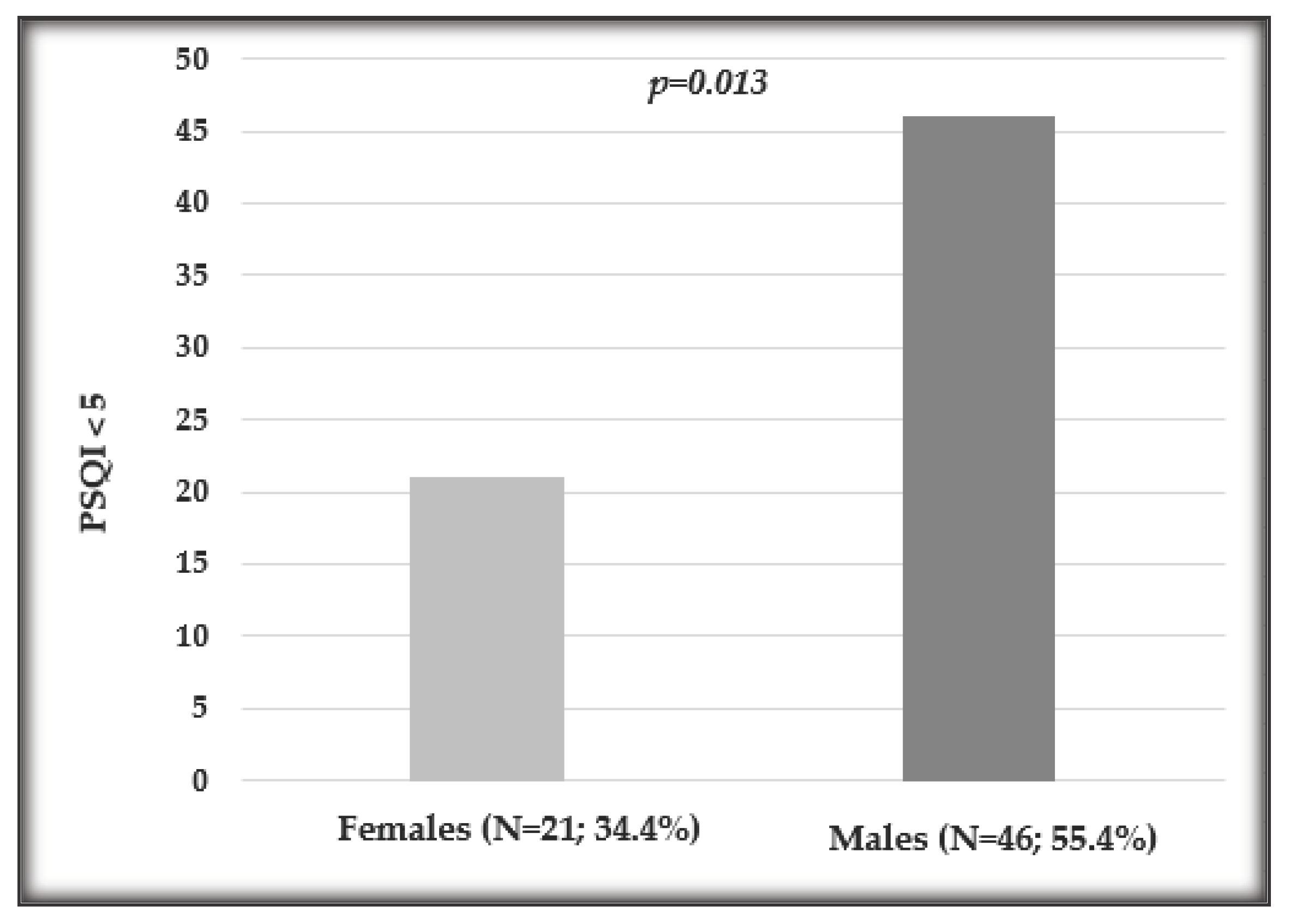

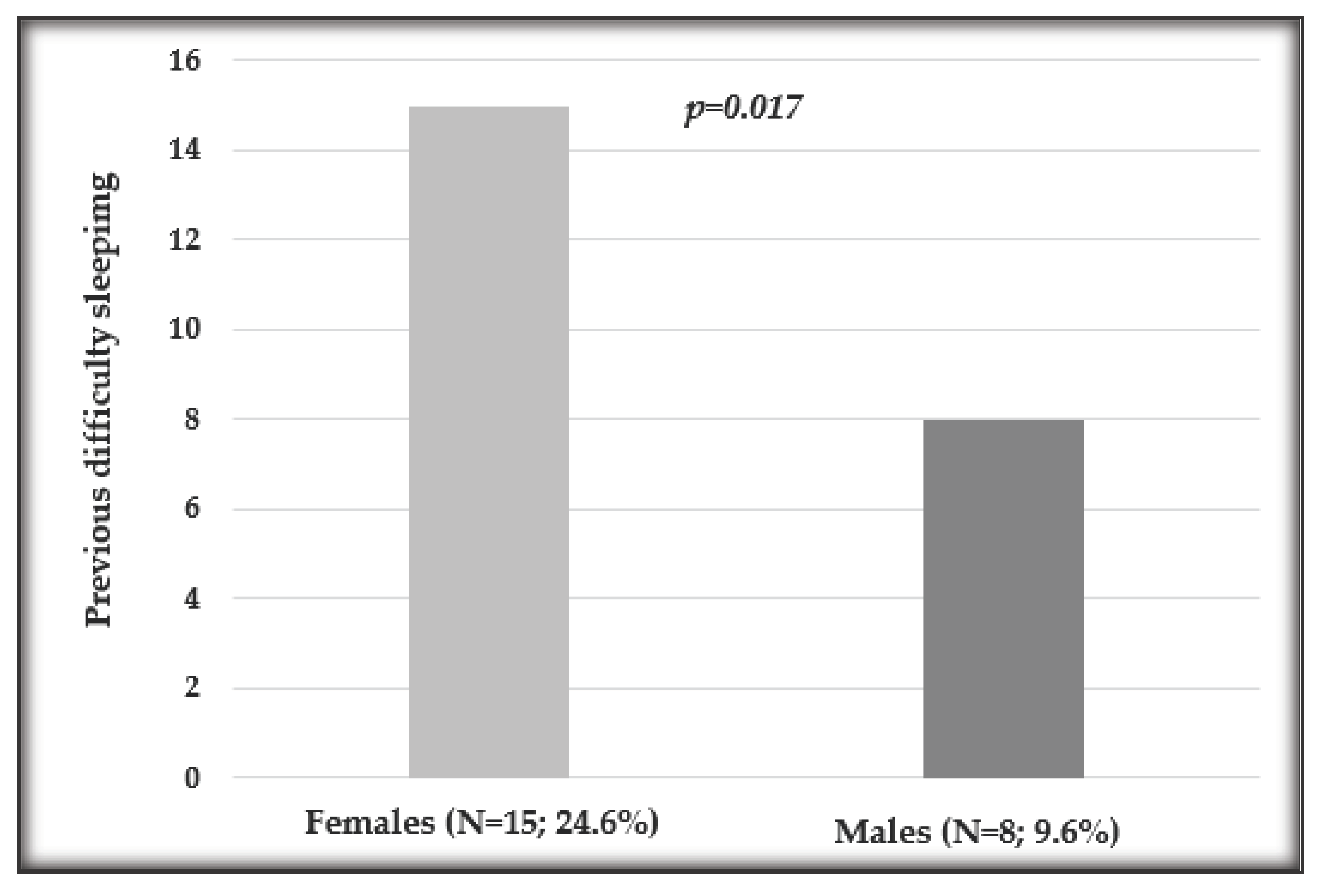

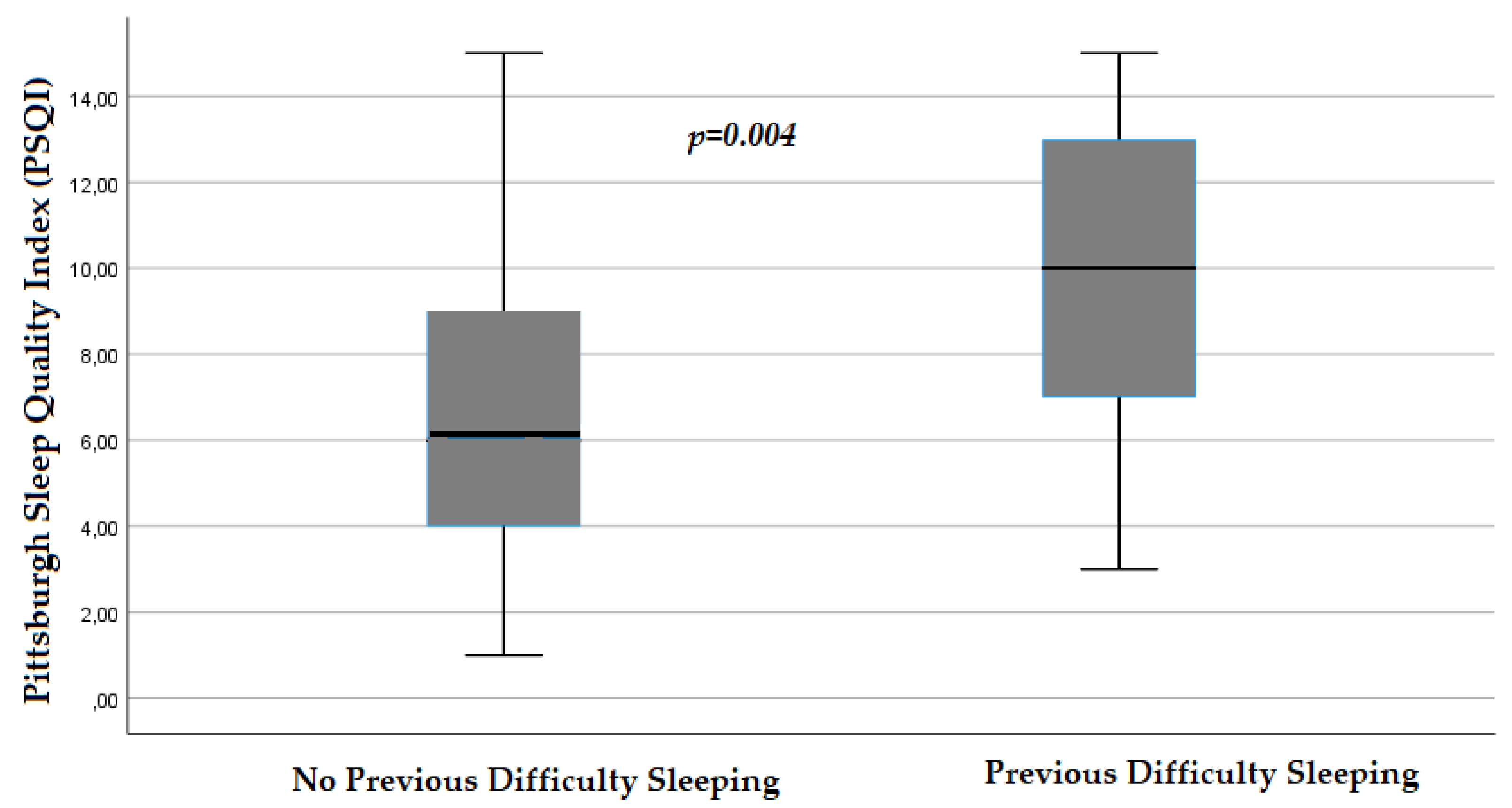

3.2. Influence of Sex on Sleep Quality

3.3. Regression Analyses

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Beltrami, F.G.; Nguyen, X.L.; Pichereau, C.; Maury, E.; Fleury, B.; Fagondes, S. Sleep in the intensive care unit. J Bras Pneumol 2015, 41, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manian, F.A.; Manian, C.J. Sleep quality in adult hospitalized patients with infection: an observational study. Am J Med Sci 2015, 349, 56–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Sha, Y.S.; Kong, Q.Q.; Woo, J.A.; Miller, A.R.; Li, H.W.; Zhou, L.X.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, C.L. Factors that affect sleep quality: perceptions made by patients in the intensive care unit after thoracic surgery. Support Care Cancer 2013, 21, 2091–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nesbitt, A.D.; Leschziner, G.D.; Peatfield, R.C. Headache, drugs and sleep. Cephalalgia 2014, 34, 756–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nesbitt, A.D. Delayed sleep-wake phase disorder. J Thorac Dis 2018, 10, S103–S111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesbitt, L.; Goode, D. Nurses perceptions of sleep in the intensive care unit environment: a literature review. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2014, 30, 231–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesbitt, A.D.; Dijk, D.J. Out of synch with society: an update on delayed sleep phase disorder. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2014, 20, 581–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J.S.; Bourgeois, J.A.; Hilty, D.M.; Hardin, K.A. Sleep in hospitalized medical patients, part 2: behavioral and pharmacological management of sleep disturbances. J Hosp Med 2009, 4, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J.S.; Bourgeois, J.A.; Hilty, D.M.; Hardin, K.A. Sleep in hospitalized medical patients, part 1: factors affecting sleep. J Hosp Med 2008, 3, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, N.H.; Arora, V.M. Sleep in Hospitalized Older Adults. Sleep Med Clin 2022, 17, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, N.H.; Arora, V.M. Sleep in Hospitalized Older Adults. Sleep Med Clin 2018, 13, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medic, G.; Wille, M.; Hemels, M.E. Short- and long-term health consequences of sleep disruption. Nat Sci Sleep 2017, 9, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonella, S. [Sleep-wake cycle in chemotherapy patients: a retrospective study]. Minerva Med 2010, 101, 135–147. [Google Scholar]

- Innominato, P.F.; Spiegel, D.; Ulusakarya, A.; Giacchetti, S.; Bjarnason, G.A.; Lévi, F.; Palesh, O. Subjective sleep and overall survival in chemotherapy-naïve patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Sleep Med 2015, 16, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernatchez, M.S.; Savard, J.; Ivers, H. Disruptions in sleep-wake cycles in community-dwelling cancer patients receiving palliative care and their correlates. Chronobiol Int 2018, 35, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, A.M.; Farr, L.A.; Kuhn, B.R.; Fischer, P.; Agrawal, S. Values of sleep/wake, activity/rest, circadian rhythms, and fatigue prior to adjuvant breast cancer chemotherapy. J Pain Symptom Manage 2007, 33, 398–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshikawa, K.; Higashijima, J.; Okitsu, H.; Miyake, H.; Yagi, T.; Miura, M.; Bando, Y.; Ando, T.; Hotchi, M.; Ishikawa, M.; et al. Effects of chemotherapy on quality of life and night-time sleep of colon cancer patients. J Med Invest 2020, 67, 338–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pengo, M.F.; Won, C.H.; Bourjeily, G. Sleep in Women Across the Life Span. Chest 2018, 154, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scher, N.; Guetta, L.; Draghi, C.; Yahiaoui, S.; Terzioglu, M.; Butaye, E.; Henriques, K.; Alavoine, M.; Elharar, A.; Guetta, A.; et al. Sleep Disorders and Quality of Life in Patients With Cancer: Prospective Observational Study of the Rafael Institute. JMIR Form Res 2022, 6, e37371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adan, A.; Fabbri, M.; Natale, V.; Prat, G. Sleep Beliefs Scale (SBS) and circadian typology. J Sleep Res 2006, 15, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curcio, G.; Tempesta, D.; Scarlata, S.; Marzano, C.; Moroni, F.; Rossini, P.M.; Ferrara, M.; De Gennaro, L. Validity of the Italian version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). Neurol Sci 2013, 34, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divani, A.; Heidari, M.E.; Ghavampour, N.; Parouhan, A.; Ahmadi, S.; Narimani Charan, O.; Shahsavari, H. Effect of cancer treatment on sleep quality in cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis of Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. Support Care Cancer 2022, 30, 4687–4697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.L.; Yu, C.T.; Yang, C.H. Sleep disturbances and quality of life in lung cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Lung Cancer 2008, 62, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, R.C.D.S.; Dos Santos, M.R.; das Chagas Valota, I.A.; Sousa, C.S.; Costa Calache, A.L.S. Factors associated with sleep quality during chemotherapy: An integrative review. Nurs Open 2020, 7, 1274–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romito, F.; Cormio, C.; De Padova, S.; Lorusso, V.; Berio, M.A.; Fimiani, F.; Piattelli, A.; Palazzo, S.; Abram, G.; Dudine, L.; et al. Patients attitudes towards sleep disturbances during chemotherapy. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2014, 23, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nzwalo, I.; Aboim, M.A.; Joaquim, N.; Marreiros, A.; Nzwalo, H. Systematic Review of the Prevalence, Predictors, and Treatment of Insomnia in Palliative Care. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2020, 37, 957–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strollo, S.E.; Fallon, E.A.; Gapstur, S.M.; Smith, T.G. Cancer-related problems, sleep quality, and sleep disturbance among long-term cancer survivors at 9-years post diagnosis. Sleep Med 2020, 65, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Innominato, P.F.; Giacchetti, S.; Bjarnason, G.A.; Focan, C.; Garufi, C.; Coudert, B.; Iacobelli, S.; Tampellini, M.; Durando, X.; Mormont, M.C.; et al. Prediction of overall survival through circadian rest-activity monitoring during chemotherapy for metastatic colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer 2012, 131, 2684–2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pai, A.; Sivanandh, B.; Udupa, K. Quality of Sleep in Patients with Cancer: A Cross-sectional Observational Study. Indian J Palliat Care 2020, 26, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Maqbali, M.; Al Sinani, M.; Alsayed, A.; Gleason, A.M. Prevalence of Sleep Disturbance in Patients With Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin Nurs Res 2022, 31, 1107–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smagula, S.F.; Stone, K.L.; Fabio, A.; Cauley, J.A. Risk factors for sleep disturbances in older adults: Evidence from prospective studies. Sleep Med Rev 2016, 25, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Bailey, D.E.; Docherty, S.L.; Porter, L.S.; Cooper, B.A.; Paul, S.M.; Hammer, M.J.; Conley, Y.P.; Levine, J.D.; Miaskowski, C. Distinct Sleep Disturbance Profiles in Patients With Gastrointestinal Cancers Receiving Chemotherapy. Cancer Nurs 2022, 45, E417–E427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Induru, R.R.; Walsh, D. Cancer-related insomnia. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2014, 31, 777–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endeshaw, D.; Biresaw, H.; Asefa, T.; Yesuf, N.N.; Yohannes, S. Sleep Quality and Associated Factors Among Adult Cancer Patients Under Treatment at Oncology Units in Amhara Region, Ethiopia. Nat Sci Sleep 2022, 14, 1049–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siefert, M.L.; Hong, F.; Valcarce, B.; Berry, D.L. Patient and clinician communication of self-reported insomnia during ambulatory cancer care clinic visits. Cancer Nurs 2014, 37, E51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strik, H.; Cassel, W.; Teepker, M.; Schulte, T.; Riera-Knorrenschild, J.; Koehler, U.; Seifart, U. Why Do Our Cancer Patients Sleep So Badly? Sleep Disorders in Cancer Patients: A Frequent Symptom with Multiple Causes. Oncol Res Treat 2021, 44, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakih, R.; Rahal, M.; Hilal, L.; Hamieh, L.; Dany, M.; Karam, S.; Shehab, L.; El Saghir, N.S.; Tfayli, A.; Salem, Z.; et al. Prevalence and Severity of Sleep Disturbances among Patients with Early Breast Cancer. Indian J Palliat Care 2018, 24, 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palesh, O.; Peppone, L.; Innominato, P.F.; Janelsins, M.; Jeong, M.; Sprod, L.; Savard, J.; Rotatori, M.; Kesler, S.; Telli, M.; et al. Prevalence, putative mechanisms, and current management of sleep problems during chemotherapy for cancer. Nat Sci Sleep 2012, 4, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bischel, L.E.; Ritchie, C.; Kober, K.M.; Paul, S.M.; Cooper, B.A.; Chen, L.M.; Levine, J.D.; Hammer, M.; Wright, F.; Miaskowski, C. Age differences in fatigue, decrements in energy, and sleep disturbance in oncology patients receiving chemotherapy. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2016, 23, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Yin, Z.; Fang, B. Measurements and status of sleep quality in patients with cancers. Support Care Cancer 2018, 26, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, I.; Kuhn, M.; Hrusak, K.; Buchler, B.; Boublikova, L.; Buchler, T. Insomnia in patients treated with checkpoint inhibitors for cancer: A meta-analysis. Front Oncol 2022, 12, 946307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akman, T.; Yavuzsen, T.; Sevgen, Z.; Ellidokuz, H.; Yilmaz, A.U. Evaluation of sleep disorders in cancer patients based on Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2015, 24, 553–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, K.F.; Lee, C.T.; Yeung, W.F.; Chan, M.S.; Chung, E.W.; Lin, W.L. Sleep hygiene education as a treatment of insomnia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fam Pract 2018, 35, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palesh, O.G.; Roscoe, J.A.; Mustian, K.M.; Roth, T.; Savard, J.; Ancoli-Israel, S.; Heckler, C.; Purnell, J.Q.; Janelsins, M.C.; Morrow, G.R. Prevalence, demographics, and psychological associations of sleep disruption in patients with cancer: University of Rochester Cancer Center-Community Clinical Oncology Program. J Clin Oncol 2010, 28, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inhestern, L.; Beierlein, V.; Bultmann, J.C.; Möller, B.; Romer, G.; Koch, U.; Bergelt, C. Anxiety and depression in working-age cancer survivors: a register-based study. BMC Cancer 2017, 17, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, W.H.; Borniger, J.C. Molecular Mechanisms of Cancer-Induced Sleep Disruption. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carney, C.E.; Edinger, J.D.; Kuchibhatla, M.; Lachowski, A.M.; Bogouslavsky, O.; Krystal, A.D.; Shapiro, C.M. Cognitive Behavioral Insomnia Therapy for Those With Insomnia and Depression: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Sleep 2017, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalmbach, D.A.; Cheng, P.; Arnedt, J.T.; Anderson, J.R.; Roth, T.; Fellman-Couture, C.; Williams, R.A.; Drake, C.L. Treating insomnia improves depression, maladaptive thinking, and hyperarousal in postmenopausal women: comparing cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBTI), sleep restriction therapy, and sleep hygiene education. Sleep Med 2019, 55, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansano-Schlosser, T.C.; Ceolim, M.F. Factors associated with sleep quality in the elderly receiving chemotherapy. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem 2012, 20, 1100–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahiya, S.; Ahluwalia, M.S.; Walia, H.K. Sleep disturbances in cancer patients: underrecognized and undertreated. Cleve Clin J Med 2013, 80, 722–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercadante, S.; Adile, C.; Ferrera, P.; Masedu, F.; Valenti, M.; Aielli, F. Sleep disturbances in advanced cancer patients admitted to a supportive/palliative care unit. Support Care Cancer 2017, 25, 1301–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, I.H.C.; Balachandran, D.D.; Faiz, S.A.; Bashoura, L.; Escalante, C.P.; Manzullo, E.F. Characteristics of Cancer-Related Fatigue and Concomitant Sleep Disturbance in Cancer Patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 2022, 63, e1–e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panossian, A. Challenges in phytotherapy research. Front Pharmacol 2023, 14, 1199516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, J. Quality, efficacy and safety of complementary medicines: fashions, facts and the future. Part I. Regulation and quality. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2003, 55, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seyed Hashemi, M.; Namiranian, N.; Tavahen, H.; Dehghanpour, A.; Rad, M.H.; Jam-Ashkezari, S.; Emtiazy, M.; Hashempur, M.H. Efficacy of Pomegranate Seed Powder on Glucose and Lipid Metabolism in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Prospective Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Complement Med Res 2021, 28, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nayebi, N.; Esteghamati, A.; Meysamie, A.; Khalili, N.; Kamalinejad, M.; Emtiazy, M.; Hashempur, M.H. The effects of a Melissa officinalis L. based product on metabolic parameters in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A randomized double-blinded controlled clinical trial. J Complement Integr Med 2019, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guadagna, S.; Barattini, D.F.; Rosu, S.; Ferini-Strambi, L. Plant Extracts for Sleep Disturbances: A Systematic Review. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2020, 2020, 3792390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alem, L.; Ansari, H.; Hajigholami, A. Evaluation of Sleep Training Effectiveness on the Quality of Sleep in Cancer Patients during Chemotherapy. Adv Biomed Res 2021, 10, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vena, C.; Parker, K.; Cunningham, M.; Clark, J.; McMillan, S. Sleep-wake disturbances in people with cancer part I: an overview of sleep, sleep regulation, and effects of disease and treatment. Oncol Nurs Forum 2004, 31, 735–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, E.E.; Wang, S.Y. Cancer-Related Sleep Wake Disturbances. Semin Oncol Nurs 2022, 38, 151253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moy, S.; Kober, K.M.; Viele, C.; Paul, S.M.; Hammer, M.; Melisko, M.; Wright, F.; Conley, Y.P.; Levine, J.D.; Miaskowski, C. Level of Exercise Influences the Severity of Fatigue, Energy Levels, and Sleep Disturbance in Oncology Outpatients Receiving Chemotherapy. Cancer Nurs 2022, 45, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Y.Y.; Hung, C.T.; Chan, J.C.; Huang, S.M.; Lee, Y.H. Meta-analysis: Exercise intervention for sleep problems in cancer patients. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2019, 28, e13131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | All (N=144) | Males (N=83) | Females (N=61) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 62 (54-68) | 62 (56-68) | 59 (52-67.5) |

| Sleep Hygiene score | |||

| Median (IQR) | 1.5 (1.18-1.90) | 1.36 (1.13-1.81) | 1.68 (1.31-2) |

| Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 6 (4-9) | 5 (4-8) | 6 (4-10) |

| PSQI≤5 (percentage, frequency) | 67, 46.5% | 46, 55.4% | 21, 34.4% |

| PSQI>5 (percentage, frequency) | 77, 53.5% | 37, 44.6% | 40, 65.6% |

| Variable | All (N=144) | Males (N=83) | Females (N=61) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Highest level of education (Frequency, Percentage) | |||

| Primary School Diploma | 4, 2.8% | 3, 3.6% | 1, 1.6% |

| Middle School Diploma | 49, 34% | 29, 34.9% | 20, 32.8% |

| High School Diploma | 62, 43.1% | 36, 43.3% | 26, 42.6% |

| Degree | 28, 19.4% | 14, 16.9% | 14, 23% |

| Marital Status (Frequency, Percentage) | |||

| Married - Cohabiting | 106, 73.6% | 64, 77.1% | 42, 68.9% |

| Separated – Divorced | 17, 11.8% | 10, 12% | 7, 11.5% |

| Unmarried Maiden | 12, 8.3% | 7, 8.4% | 5, 8.3% |

| Widow | 8, 5.6% | 1, 1.2% | 7, 11.5% |

| Tumour Localization (Frequency, Percentage) | |||

| Lungs | 6, 4.2% | 4, 4.8% | 2, 3.3% |

| Intestine | 92, 63.9% | 51, 61.4% | 41, 67.2% |

| Stomach, Esophagus | 27, 18.8% | 19, 22.9% | 8, 13.1% |

| Liver And Biliary Tract | 5, 3.5% | 2, 2.4% | 3, 4.9% |

| Pancreas | 13, 9% | 8, 9.6% | 5, 8.2% |

| Genitourinary Tract | 1, 0.7% | 0 | 1, 1.6% |

| Chemotherapy Administration (Frequency, Percentage) | |||

| Intravenous | 144, 100% | 83, 100% | 61, 100% |

| Oral | 23, 16% | 15, 18.1% | 8, 13.1% |

| Central Venous Catheter (Frequency, Percentage) | |||

| Present | 143, 99.1% | 82, 98.8% | 61, 100% |

| Stoma (Frequency, Percentage) | |||

| Present | 16, 11.1% | 11, 13.3% | 5, 8.2% |

| Nutrition (Frequency, Percentage) | |||

| Oral | 141, 97.9% | 80, 96.4% | 59, 96.7% |

| Parenteral | 3, 2.1% | 2, 2.4% | 1, 1.6% |

| Pain Sensation (Frequency, Percentage) | |||

| Present | 32, 22.2% | 15, 18.1% | 17, 27.9% |

| Pain Relievers (Frequency, Percentage) | |||

| Paracetamol | 20, 13.9% | 10, 12% | 10, 6.4% |

| Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatories | 4, 2.8% | 2, 2.4% | 2, 3.3% |

| Opioids | 11, 7.6% | 6, 7.2% | 5, 8.2% |

| Concomitant Pathologies (Frequency, Percentage) | |||

| Cardiovascular Diseases | 48, 33.3% | 27, 32.5% | 21, 34.4% |

| Diabetes | 15, 10.4% | 12, 14.5% | 3, 4.9% |

| Endocrine Disorders | 9, 6.3% | 2, 2.4% | 7, 11.5% |

| Psychiatric Disorders | 6, 4.2% | 2, 2.4% | 4, 6.6% |

| Arthritis, Arthrosis, Osteoporosis, Rheumatic Disorders | 4, 2.8% | 1, 1.2% | 3, 4.9% |

| Gastric Disorders | 3, 2.1% | 1, 1.2% | 2, 3.3% |

| Intestinal Disorders | 1, 0.7% | 1, 1.1% | 0 |

| Genitourinary Disorders | 2, 1.4% | 2, 2.4% | 0 |

| Neurological Disorders | 3, 2.1% | 3, 3.6% | 0 |

| Respiratory Disorders | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Concomitant Therapies (Frequency, Percentage) | |||

| Corticosteroids | 68, 47.2% | 32, 38.6% | 36, 59% |

| Antiemetics | 67, 46.5% | 35, 42.2% | 32, 52.5% |

| Drugs For Cardiovascular Diseases | 56, 38.9% | 36, 43.4% | 20, 32.8% |

| Antidepressants | 7, 4.9% | 2, 2.4% | 5, 8.2% |

| Benzodiazepines | 7, 4.9% | 4, 4.8% | 3, 4.9% |

| Drugs For Thyroid Diseases | 9, 6.3% | 2, 2.4% | 7, 11.5% |

| Insulin And Oral Hypoglycemics | 13, 9% | 10, 12% | 3, 4.9% |

| Antihistamines | 8, 5.6% | 6, 7.2% | 2, 3.3% |

| Antipsychotics/Mood Stabilizers | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Antiepileptics/Anticonvulsants | 1, 0.7% | 1, 1.2% | 0 |

| Previous Difficulty Sleeping (Frequency, Percentage) | |||

| Yes | 23, 16% | 8, 9.6% | 15, 24.6% |

| Treatment For Difficulty Sleeping (Frequency, Percentage) | |||

| Phytotherapeutics | 2, 1.4% | 1, 1.2% | 1, 1.6% |

| Melatonin | 1, 0.7% | 0 | 1, 1.6% |

| Chamomile And Herbal Teas | 4, 2.8% | 3, 3.6% | 1, 1.6% |

| Drugs | 10, 6.9% | 3, 3.6% | 7, 11.5% |

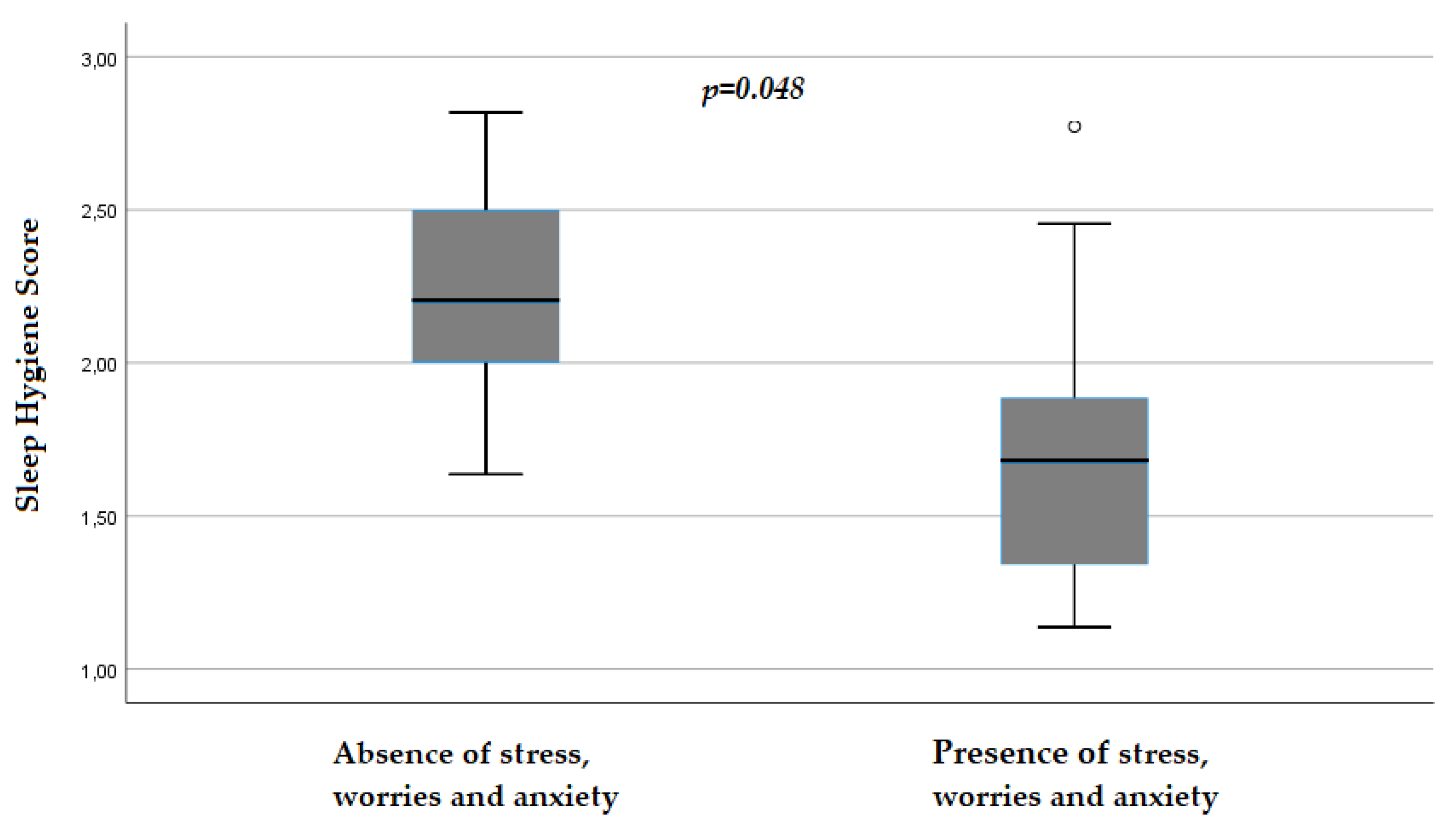

| Stress/Worries/Anxiety (Frequency, Percentage) | |||

| Yes | 18, 12.5% | 11, 13.25% | 7, 11.48% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).