Introduction

The prevalence of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is considered to be increasing and has become a “serious problem” in modern society [

1], however, the pathogenesis that underlies this condition and the cause(s) of this rapid increase remain unclear. In any case, the early diagnosis and treatment of ASD are desired under these circumstances.

Although some prodromes in ASD have been reported by 6-12 months of age [

2,

3], no clear symptoms leading to a diagnosis have been confirmed. Thus, the initial diagnosis is generally made at around 1.5-3 years of age. At this time, impaired social communication, which is considered to be one of the main symptoms of ASD, becomes apparent.

On the other hand, abnormal behaviors of individuals with ASD have been recognized, even in the newborn period, including crying infrequently or not seeking human interaction or stimulation and/or conversely being intensely irritable and overreactive to any form of stimulation [

4]. The former has been called “apathetic type” or “under-reactive type” neonates, while the latter has been called “irritable type” or “over-reactive type” neonates.

Although less noticeable, sleep disorder should be added as a prodromal symptom in ASD, because it is well known to be a major symptom of ASD in infancy/early childhood [

5,

6], as well as in children and adolescents [

7]. Importantly, sleep disorder in ASD is recognized as a circadian rhythm abnormality [

8,

9,

10].

In fact, the sleep disorders observed in ASD include increased bedtime resistance, insomnia, awakening, morning waking difficulties, and daytime sleepiness, which suggests the existence of circadian rhythm abnormalities [

11].

If the incidence of ASD really is increasing in modern society, then it is important to identify the most influential changes in the living environment that are detrimental to modern human health. Because many pathological conditions are known to develop with the addition of living environmental factors, even with a genetic background.

From this viewpoint, it makes the most sense to pay attention to biological clock formation, which controls human life-sustaining functions [

12,

13]. In addition, it is well-recognized that the sleep/wake rhythm is controlled by the biological clock. In the brain, sleep is associated with brain development, growth, damage repair, protection of the brain function and further evolution. However, in modern society, the sleeping environment has changed drastically and the sleeping environment of children continues to be exacerbated. For example, in Japan the most common sleep-onset time in infancy was around 20:00 in the 1960s, while at the present time, 10-30% of children fall asleep after 22:00, which equates to a more than 2-hour shift of daily life.

Considering the sleep-wake rhythm is quite meaningful when discussing the mental and physical development and health of children [

14]. In the present study, we would like to express new concepts about ASD from a chronobiological viewpoint [10, 11, 15, 16], and would like to discuss a possible treatment strategy. We hope this study will provide information that improves the understanding of problems in biological clock formation as an important background factor for sleep disorders in ASD and ASD itself.

Results

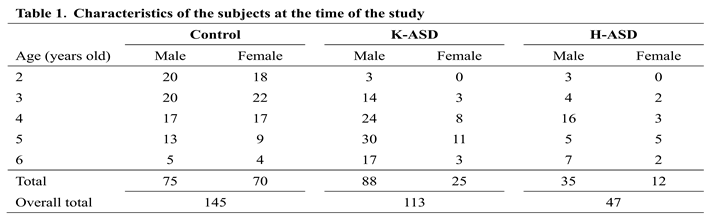

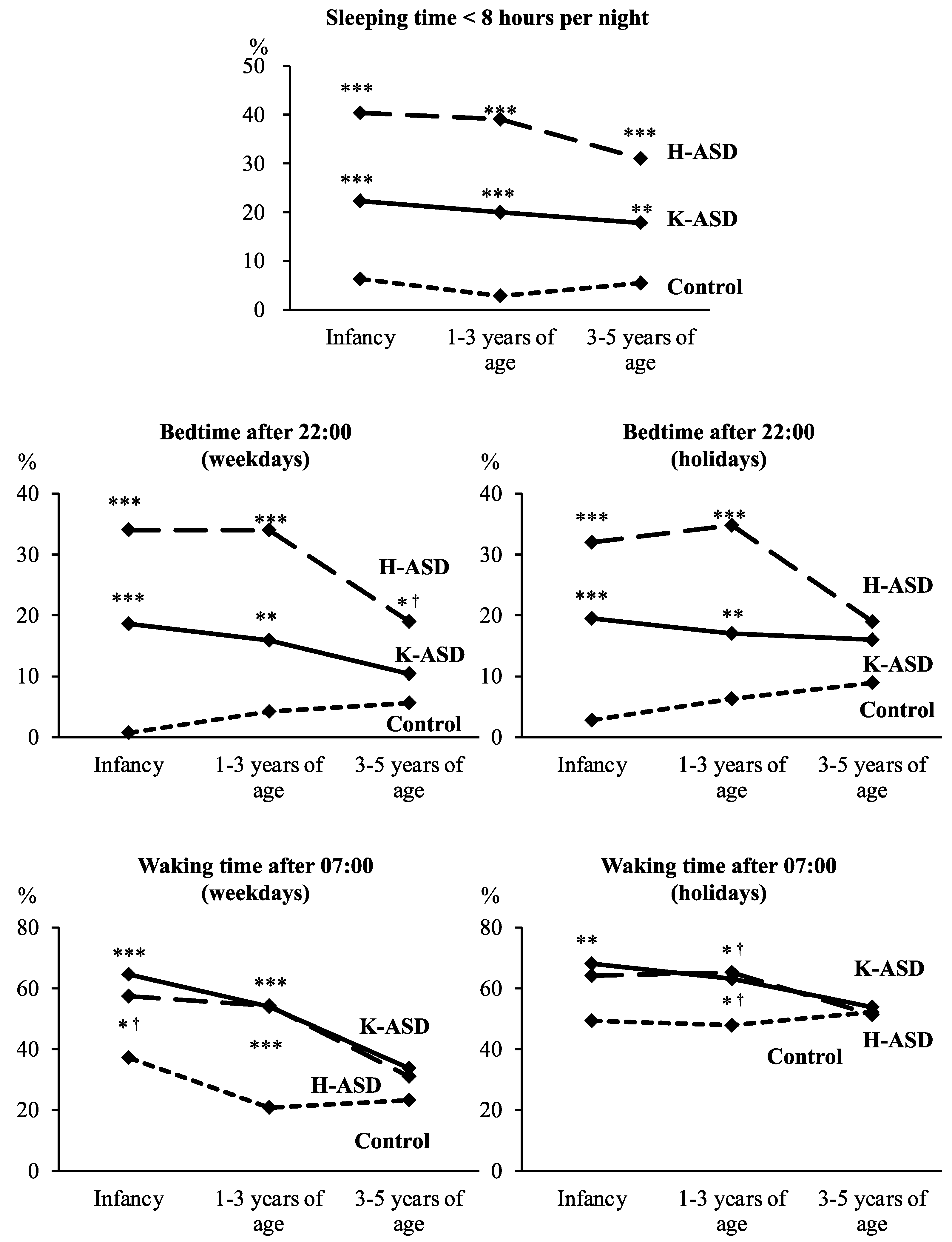

First, we compared the rats of sleeping time <8 hours per night, bedtime after 22:00 and waking time after 7:00 in infancy, at 1–3 years of age, and at 3–5 years of age between the ASD groups and the control group (

Figure 1). In both ASD groups, the rates of sleeping time <8 hours per night in infancy, at 1-3 years of age, and at 3-5 years of age were significantly higher in comparison to the control group (

Figure 1). In both ASD groups, the rates of bedtime after 22:00 on weekdays in infancy and at 1-3 years of age, and on holidays in infancy and at 1-3 years of age were significantly higher in comparison to the control group (

Figure 1). In the K-ASD group—but not the H-ASD group—the rates of waking time after 7:00 on weekdays in infancy and at 1-3 years of age (

Figure 1), and on holidays in infancy and at 1-3 years of age were significantly higher in comparison to the control group (

Figure 1). On the other hand, there was no difference between the ASD groups and the control group in the rates of bedtime after 22:00 and waking time after 7:00 at 3-5 years of age (

Figure 1).

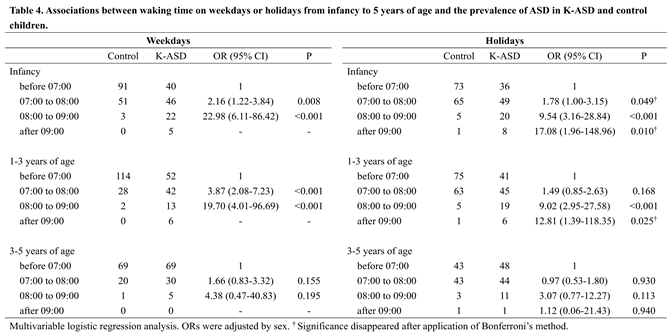

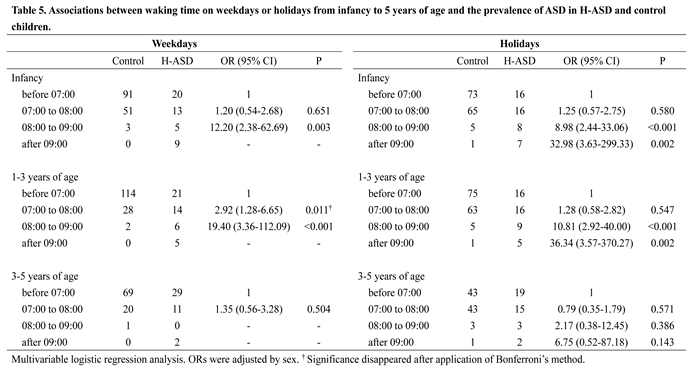

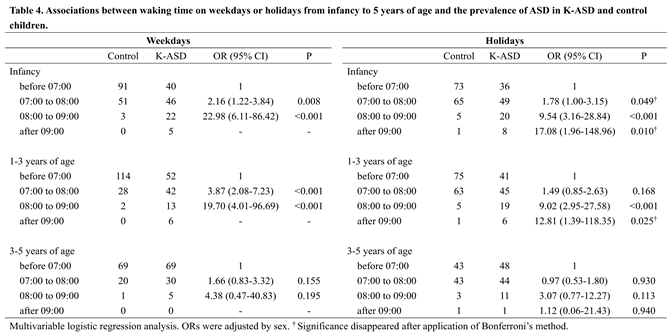

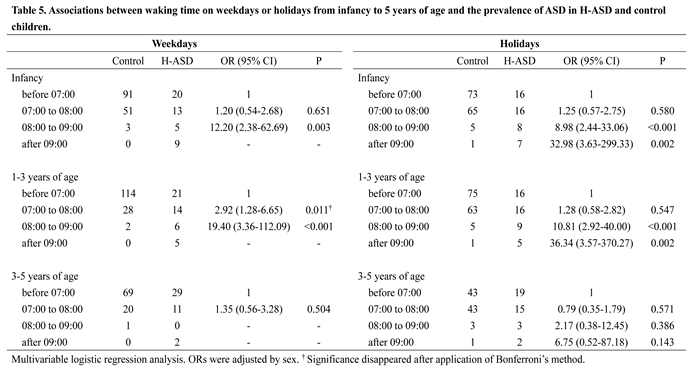

Next, we analyzed the associations of bedtime and waking time on weekdays and holidays in infancy, at 1-3≧ years of age, and at 3-5 years of age with the prevalence of ASD using a multivariable logistic regression analysis (Tables 2–5). Bedtimes of 22:00 to 23:00 on weekdays and on holidays, and 23:00 to 0:00 on holidays in infancy were associated with the prevalence of ASD (Tables 2 and 3). Bedtimes of 22:00 to 23:00 on weekdays and on holidays at 1-3 years of age were associated with the prevalence of ASD (Tables 2 and 3). On the other hand, no association was observed between bedtime at 3-5 years of age and the prevalence of ASD (Tables 2 and 3). However, it should be noted that some children with ASD went to bed after 23:00 from infancy to 5 years of age, while few or no children in the control group went to bed at these times, and some ORs for bedtime 23:00 to 0:00 and after 0:00 could not be calculated (Tables 2 and 3). Waking times of 7:00 to 8:00 and 8:00 to 9:00 on weekdays and on holidays, and after 9:00 on holidays in infancy and at 1-3 years of age were associated with the prevalence of ASD (Tables 4 and 5). In addition, waking times of 7:00 to 8:00 on weekdays and 8:00 to 9:00 on holidays at 3-5 years of age were associated with the prevalence of ASD (Tables 4 and 5). However, it should also be noted that some children with ASD woke up after 9:00 on weekdays from infancy to 5 years of age, while no children in the control group woke up at the time, and ORs for waking time after 9:00 on weekdays could not be calculated (Tables 2–5).

|

|

|

|

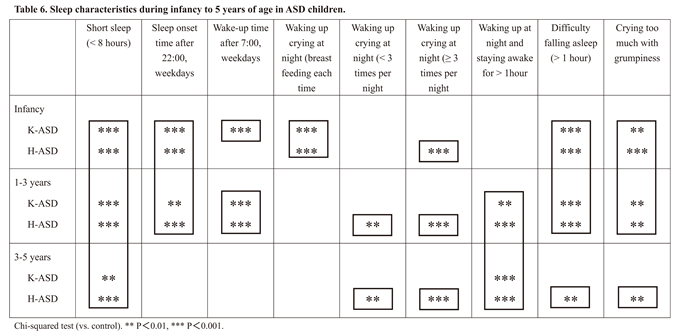

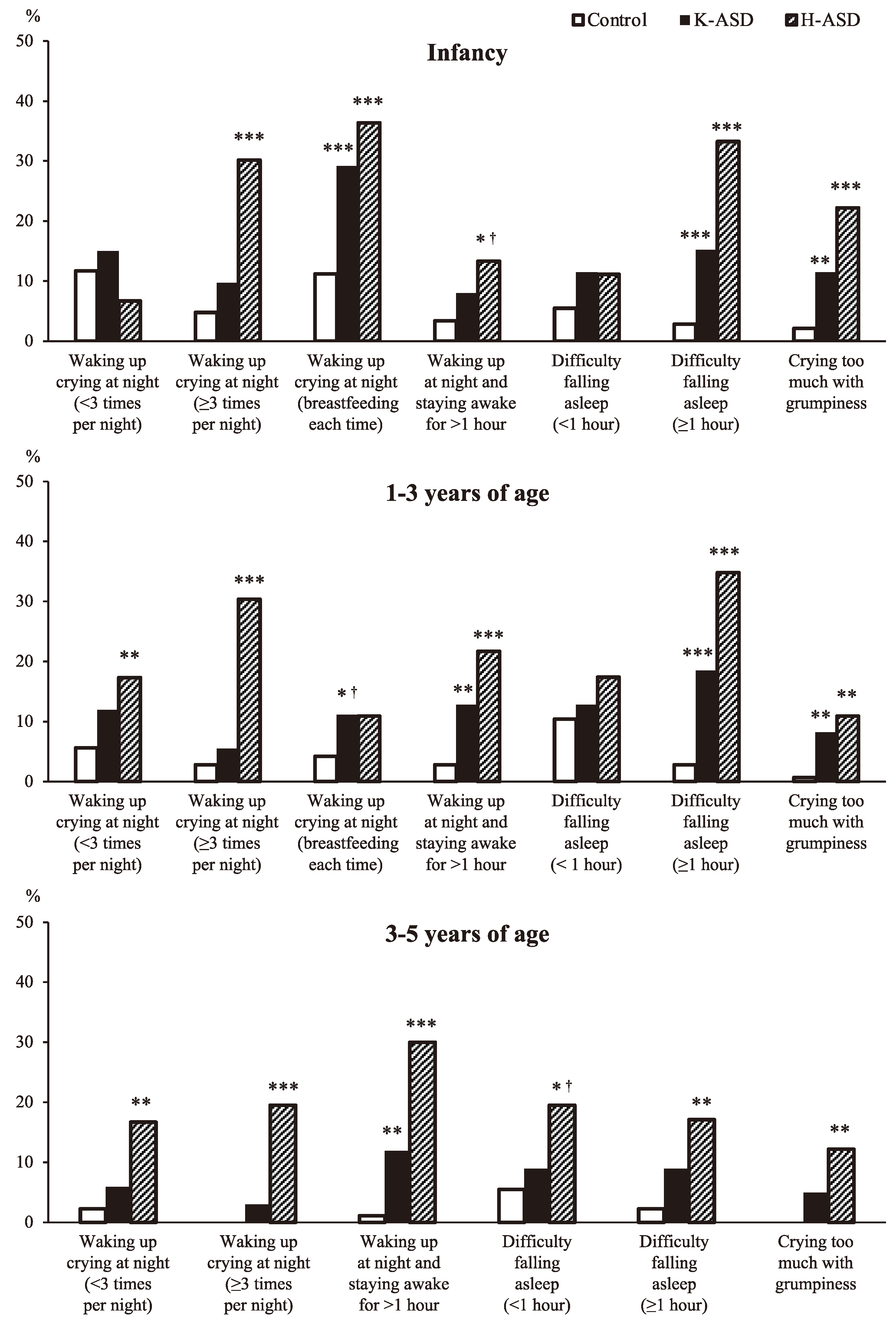

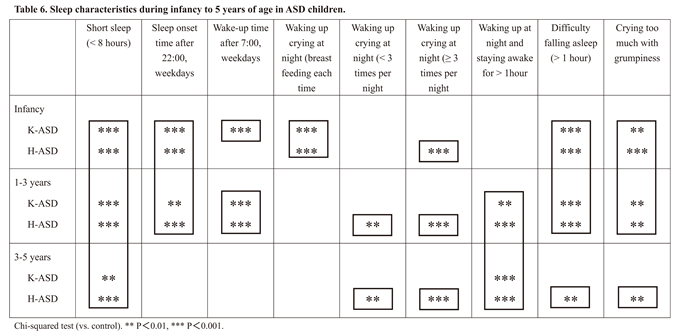

Finally, we analyzed whether there were differences between children with ASD and the control group in the presence or absence of characteristics of sleep disturbances from infancy to 5 years of age (

Figure 2). During infancy, the rate of breastfeeding at each time and the child's awakening was significantly higher in both ASD groups. In the H-ASD group, from infancy to 5 years of age, the rate of crying awakening at night 3 or more times was significantly higher, than that in the control group (Table 4). On the other hand, in the K-ASD group, although the rate tended to be higher, the difference did not reach statistical significance (

Figure 2). The rates of difficulty falling asleep (≧1 hour) and crying too much with grumpiness at infancy and 1-3 years of age were higher in both ASD groups than in the control group. (

Figure 2) The rates of waking up at night and staying awake for more than 1 hour at 1-3 years and 3-5 years of age were higher in both ASD groups than in the control group (

Figure 2). Table 6 shows a summary of the results of this study.

|

Discussion

The results of this study suggest that abnormalities in sleep/wake rhythms, as shown in Table 6, that are common in infancy and early childhood, may be closely associated with the future development of ASD.

Actually, it has been suggested that biological rhythm disorders, including sleep-wake rhythm in ASD, are not only associated symptoms, but also deeply related to the pathogenesis [

15,

16,

17,

18]. More importantly, the circadian rhythm's biological clock controls so-called life-support systems (e.g., the autonomic nervous system, hormone secretion, thermoregulation, energy metabolism, the immune system, coordinated movement, and maintenance of the brain function balance [

13,

16]. Therefore, the chrono-biological theory is logical and convincing for understanding and/or explaining various clinical manifestations of ASD [

15,

16,

19], including sleep disorder, epilepsy, enuresis, autonomic disorder, language problems, intellectual disabilities, gastrointestinal symptoms, diabetes, and depression.

However, whether the onset of ASD is a primary matter, and sleep disorder is only a secondary concomitant symptom [

20] and conversely, whether sleep disorder appears first as a main cause of ASD development [

17,

18], have long been matters of debate. In drawing conclusions, we would like to introduce an important report that emphasized that—under all circumstances—children with sleep disorder require quick treatment, and there is recognition of the fact that sleep disorder has a negative effect on children’s growth and development [

21,

22,

23].

From infancy to 5 years of age, some of these sleep problems change slightly and tend to improve with age, while others persist throughout the period. For example, the frequency of night awakenings and daytime crying and grumpiness tends to improve with age. On the other hand, short sleep (<8 hours at night), awakening at night for >1 hour, and the onset of sleep lasting >1 hour, persist as characteristic symptoms suggesting that they may serve as predictors of the future development of ASD. The above-mentioned sleep-wake rhythm abnormalities are considered to be characterized by impaired sleep persistence at night and inadequate late sleep onset (in other words, shifted sleep onset), and as a result late awakening time. In other words, the background of these symptoms may be the immaturity and/or misalignment (including shift) of circadian biological clock formation. In fact, circadian rhythm sleep disorder, which also falls within the definition of chrono-disruption [

13,

24,

25], has already been reported before the onset of ASD [

17], and suggested even in neonates [

4,

18].

It has been reported that the expected night time sleep duration is approximately 5-6 hours at 2 months [

26], 8-9 hours at 4 months [

27], and 8-12 hours at 6-7 months [

28]. Thus, it has been reported that children who can maintain a good night's sleep have a high self-soothing ability [

27,

29], and therefore, cry less at night. In order to foster self-soothing habits, it is necessary to improve the response of the guardian who reaches out as soon as the baby cries [

30]. These reports suggest, that infants who can already sleep through the whole night (8-12 hours) from 4-6 months of age do not require night feeding [

27]. In addition, our data show that the performance of breast feeding during each time nighttime awakening during infancy can interfere with sleep and thus contribute to the development of future sleep disorder, possibly ASD itself.

A study of children of 6 months to 4 years of age in Canada [

31] reported that most children nighttime sleep duration of 10 hours (47.6%) or 11 hours (42.8%). On the other hand, according to our unpublished data from approximately 5000 Japanese children of 2 months to 7 years of age, the study population slept 9-11 hours at night (average 10 hours). We called 9-11 hours of sleep the "night-time basic sleep duration (NBSD)," which we considered to be the duration of sleep required from infancy to 9 years of age (data not shown).

We have no explanation for the background of short sleep (<8 hours). However,

when efforts are made to adequately correct sleep-wake rhythm, the sleep duration sometimes became longer than before treatment, which suggests that an inadequate timing system is one of the background factors. These data suggest that, in addition to their innate nature, short sleep occurs in part due to night-shift in daily life (the so-called “owl type”). In addition to the length of sleep, it is important to sleep continuously throughout the night without waking up. Therefore, it is necessary to pay attention when an individual awakens three or more times at night [

32,

33] or when they awaken for 20 minutes (ICSD-3) or more. According to our data, individuals who awaken three or more times or who awaken for more than 60 minutes should be treated for sleep fragmentation and/or sleep persistence disorder, especially from the latter half of infancy to early childhood.

More importantly and interestingly, individuals with a late bedtime (after 22:00 and especially after 23:00) and a late morning waking time (after 7:00 and especially after 8:00) showed a higher risk ratio for future ASD (refer to Tables & Figures). This phenomenon is expressed by difficulty in falling asleep (poor sleep onset), which is significantly observed in children with ASD from infancy to early childhood. The phenomenon indicates a situation in which the function of the biological clock cannot induce sleep in an appropriate time zone, and can be interpreted as a deviation of the living time zone (shifted biological clock). In addition, we must also give due consideration to the genetic background [

34], especially Clock gene [

35] . This delayed sleep onset time is considered to be a so-called delayed sleep phase, and mutation in the period 2 gene was reported as a background factor of the phenomenon in ASD [

36]. According to this information, it may be important to know when and how the circadian rhythms are formed. The formation of chronobiology is known to be deeply related to the relationship between mother and fetus during pregnancy [

37,

38]. Importantly, recent paper reported that the children of mothers who had slept for less than 6 h or longer than 10 h a night were more likely to have ASD. Thus, improving sleep and increasing exercise during pregnancy might reduce the risk of ASD in their children [

39]. It has also been reported that sleep-awake rhythm abnormalities in neonates, such as sleep onset difficulty, frequent awakening, short sleep, and grumpiness during the day (the so-called “irritable type”) may be the background of the difficulty of raising resulted in abuse sometimes and considered to be precursors to the future development of ASD [

18]

.

This information should not be considered to criticize the expectant mothers or the family's lifestyle, but should be regarded as information for protect the physical and mental health and well-being of both babies and their family members.

A newborn’s daily life is mainly controlled by the ultradian cycle, with a sleep-wake rhythm of approximately three and/or four hours [

40]. In addition, the formation of the chronobiological circadian clock also starts in the fetal period [

37] and is thought to be completed at approximately 1 year and 6 months after birth [

31,

38]. Interestingly, Bruni et al. reported that sleep patterns change during the first year of life but that most sleep variables (i.e., sleep latency and duration) showed little variation from 6 to 12 months. The data provide a context for clinicians to discuss sleep issues with parents and suggest that prevention efforts should focus on the first 3-6 months, since sleep patterns show stability from that time point to 12 months [

41]. Thus, it can be inferred that it is important to start treatment for circadian rhythm sleep-wake abnormalities in infancy and/or early childhood, before the circadian rhythms are completely formed and before the function is fixed. Perhaps this can be considered a prophylactic treatment for ASD, as this is also a time when clinical symptoms (other than the sleep-wake rhythm) are unclear. It is therefore possible to say that performing treatment for sleep disorder in infancy—especially adjusting the sleep-awake circadian rhythm and correcting nocturnal awakening—may have a preventive effect against the future onset of ASD.

Considering that the circadian rhythm biological clock is almost completed after 1 year and 6 months of age, a report recommended that the sleep onset time be set to 19:00 to 20:00 by 1-4 months after birth [

28]. This is considered to be important for the formation of an appropriate circadian rhythm. In addition, the formation of an appropriate biological clock will be more suitable for the child’s future school and social life. Natural awakening from 6:00 to 7:00 is an extremely important habit. Since it is necessary to secure the length of the NBSD, the appropriate sleep onset time is 19:00 for children with an NBSD of 11 hours and 20:00 for children with an NBSD of 10 hours. I

t has been recommended that night sleep should be from 19:00 to 07:00. We have recommended that—in early infancy—the sleep onset time be set between 19:00 and 21:00. This is because an appropriate sleep-wake habit is useful for ensuring a comfortable daily life and balanced development of the child (Paul et al. 2016), and prevents the future onset of ASD. We would like to emphasize that—based on our experience in daily medical care—adjustment of the sleep wake rhythm can achieve significant improvement in the core symptoms of ASD.

For children, during infancy, the whole family needs to work together to develop the habit of falling asleep from 19:00 to before 21:00.

It is recommended that the whole family finish their meals, bathing and other activities by 19:00 to 20:00, turn off the lights at an appropriate time and sleep with the whole family for 10-14 days. In many cases, this method works. However, it does not work as well for children with such characteristics as an irritable disposition which occurs during the neonatal period. Since the response from the newborn period has not yet been established, it makes sense to monitor the progress and correct the daily life rhythm at an appropriate time after entering the infancy period (e.g., 3-6 months). This is based on the idea that the correction of sleep/wake rhythms may be able to properly engage the gears of the biological clock of the whole body.

Since sleeping at night in infants is a transition period from ultradian-rhythm to circadian-rhythm, awakening at a certain time (1-4 hours) is physiologically likely to occur. As a response to this awakening and/or false awakening, there is a strong tendency for the Japanese guardian to encourage children to fall asleep again by breastfeeding every time. In other words, breastfeeding is often used to deal with midnight awakening in infancy and very early childhood. It is known that children with night-time feeding habits tend to experience more frequent awakening. Some reports have called attention to the fact that frequent care by parents during nighttime awakening of children, especially food intake (breast milk, milk, tea, water, etc.) stimulates the peripheral (visceral) clock, causing an arousal reaction and sleep disorder [

42,

43,

44].

For frequent night awakening (>3 times) from 2 months of age, guardians should not respond immediately and instead should watch over the child to help them fall asleep naturally (self-soothing) [

44,

45,

46]. In addition, it has been recommended that night feeding be discontinued after the neonatal period, and/or that the number of feedings be reduced from 2 months and that feeding be discontinued by 3-4 months of age. As mentioned above, it is known that nighttime sleep duration is extended to 8-9 hours at 4 months of age, and feeding is not always physically or nutritionally necessary [

27,

28]

.

In addition to the genetic predisposition and the child-rearing environment, it is also important to review the modern night-time society, which has an adverse effect on children's sleeping environment. The International Survey Research on Home Education in Early Childhood, which covered working parents with young children, was carried out in metropolitan areas of four countries (Japan, China, Indonesia, Finland), in 2018. The result showed that the home-coming time of mothers in Japan and China peaked at 18:00 to 19:00 while that of mothers in Indonesia and Finland peaked at 16:00 to 17:00. The home-coming time of fathers in Japan ranged from 19:00 to 00:00, while that in China peaked at 18:00 and 19:00, that in Indonesia peaked at 19:00 and 20:00, and that in Finland peaked at 16:00 to 17:00. The home-coming time of fathers in Japan was remarkably later in comparison to fathers in other countries.

Nowadays, the nocturnal lifestyle habits of modern people who work or remain active late at night under bright lights have become part of the daily routine not only in Japan but also in other countries across the world. The sleep-onset time of children involved in such a late-night lifestyle is apt to become late, even close to midnight, especially on weekends. Society (guardians) needs to consider children who grow up in such a poor sleeping environment.