1. Introduction

Central venous catheter (CVC)-associated bacteremia is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality among our hemodialysis patients. The incidence rate ranges between 1.1 and 6.1 episodes per 1000 catheter days according to some large-scale series [

1,

2].

Both national and international guidelines recommend, whenever possible, the arteriovenous fistula as the preferred vascular access [

3,

4]. However, a substantial percentage of end-stage chronic kidney disease patients initiate hemodialysis using a catheter, and prevalent patients may choose it as their definitive vascular access [

5]. In this context, standardizing protocols across different hemodialysis units [

4] and having a specialized multidisciplinary vascular access team are crucial to minimize complication rates, mortality, and consequently, associated costs [

6].

During the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus pandemic, certain preventive measures for airborne transmission were implemented, which seem to have had a collateral benefit in reducing episodes of catheter-associated bacteremia in hemodialysis patients [

7,

8].

The objective of our study was to characterize the episodes of bacteremia in our hospital-based hemodialysis unit. Additionally, we analyzed the seasonal distribution and assessed possible variations in incidence during the peripandemic years.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Population and Study Design

We conducted a single-center, observational, and retrospective study in the hospital-based hemodialysis unit at Severo Ochoa University Hospital (Leganés, Madrid). The study included all prevalent hemodialysis patients with tunneled central venous catheters who were admitted for catheter-associated bacteremia from January 2013 to December 2022. Catheter insertion was performed by the interventional vascular radiology service under local anesthesia and standard sterile measures. Nasal carriage screening for Staphylococcus aureus was not conducted, reserving it for patients with confirmed bacteremia caused by this microorganism and treating those with positive results with nasal mupirocin. Catheter sealing was standardized using Tauro-LockTM heparin (taurolidine and heparin) during the initial days to prevent biofilm formation. Subsequently, only heparin was used, and the continuation of taurolidine was individualized based on infectious risk. Before 2018, only heparin was used for the initial sealing due to the unavailability of Tauro-LockTM heparin. Hygiene measures mandated by the unit’s protocol included the use of sterile gloves by nursing staff, surgical masks by both nursing staff and patients, and line disinfection using chlorhexidine. The definition of catheter-associated bacteremia was established by the simultaneous growth of the same microorganism in blood extracted from the central line (arterial and venous branches) and peripheral line or only from the peripheral line in catheter carriers, with the absence of other suspicious infection foci. However, episodes with a high suspicion, initiation of antibiotic therapy, and negative microbiological isolation were not excluded from the study.

2.2. Data Collection

Patient demographic data (age, gender) and comorbidities (Charlson index) were extracted from medical records: collected on paper until 2015 and computerized thereafter through the Selene® health program. Similarly, information related to hospitalization episodes (date and duration of admission, ICU stay, complications, catheter removal, microbiological isolation) as well as previous hospitalizations for bacteremia was extracted this way. Dialysis (start date, cause of end-stage renal disease) and vascular access data (location, insertion date) were extracted from the Nefrolink® software.

2.3. Objectives

The main objective was the descriptive analysis of hospitalization episodes due to catheter-associated bacteremia in dialysis patients. As a secondary objective, the annual incidence rate (expressed as episodes/1000 catheter days) was analyzed to assess the possible impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics® version 25.0. Categorical variables were reported as proportions, and continuous variables were presented as means (with 95% confidence intervals) or medians (with interquartile range) based on normal or non-normal distribution. Contingency tables were created for comparisons of categorical variables using the Spearman chi-square test or continuous variables using the Student’s t-test or Wilcoxon test depending on their distribution. The odds ratio (OR) was used to compare annual incidences. Statistically significant values were considered those with a p-value < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Patient characteristics

Over the 10-year study period, a total of 466 catheters were inserted in our center for 426 patients. Only 27.5% of patients who initiated hemodialysis during the study years remained catheter-free. We recorded 67 episodes of bacteremia in 52 patients, corresponding to an overall incidence rate of 0.52 episodes per 1000 catheter days. Patient characteristics are summarized in

Table 1.

The mean age was 67 years (range 56-78), with 74.6% being male and 25.4% female. The median Charlson comorbidity index was 8 (range 6-9). Diabetic kidney disease was the primary etiology of chronic kidney disease (43.3%), followed by nephroangiosclerosis (28.4%) and glomerular pathology (16.4%). The median time on hemodialysis was 24 months (range 4-48). The predominant catheter location was the internal jugular vein (89.5%), with only a small portion having tunneled femoral catheters (10.5%). The median catheter lifespan until infection was 240 days (range 28-930). Four patients (7.69%) were receiving some form of immunosuppressive treatment at the time of infection; three were on corticosteroids as monotherapy for various reasons (recent failed kidney transplant, rheumatoid arthritis, and corticosteroid-dependent nonspecific inflammatory syndrome), and the remaining patient was on corticosteroids and azathioprine due to having a heart transplant.

3.2. Infection characteristics

The characteristics of hospitalization episodes due to bacteremia are summarized in

Table 2.

Out of all episodes, 17 (25.3%) occurred within the first 30 days of catheter insertion; among these, 16 were caused by Gram-positive microorganisms (12 Staphylococcus aureus and 4 Staphylococcus epidermidis), while only 1 involved a Gram-negative organism (Pseudomonas aeruginosa).

Most hospitalizations took place in the summer (43.3%) and spring (23.9%), with fewer episodes recorded in the fall (16.4%) and winter (16.4%). These differences were statistically significant when comparing the summer period with fall and winter.

Microbiological confirmation was obtained in 61 out of the 67 episodes labeled as catheter-associated bacteremia. The majority isolated a Gram-positive microorganism (67.2%). Among them, Staphylococcus aureus was the most prevalent (83%), with 14.7% being methicillin-resistant strains. In the remaining cases, Staphylococcus epidermidis (14.6%) and Staphylococcus hominis (2.4%) were isolated. Among Gram-negative varieties, Klebsiella pneumoniae (35%) was the most frequently isolated, followed by Escherichia coli (20%) and Serratia marcescens (10%), with others such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Proteus mirabilis, Klebsiella oxytoca, Morganella morgagni, and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia found in smaller proportions. There were two cases of polymicrobial infections involving Gram-negative bacteria (3.2% of the total). No fungal infections were recorded during the study period.

The median hospital stay was 7 days (range 5-12), with a minimum duration of 2 days and a maximum of 81 days. Five patients (7.4%) required admission to an intensive care unit (three cases due to Staphylococcus aureus, one case due to Klebsiella pneumoniae, and one polymicrobial case involving Klebsiella pneumoniae and Proteus mirabilis). Two cases of endocarditis were identified as metastatic complications (2.9%). There were no deaths directly related to the episodes of bacteremia.

The catheter was removed in 67.1% of cases, with a statistically significant difference between Gram-positive (removed in 90.2% of cases) and Gram-negative cases (removed in 30% of cases, with the remaining cases receiving prolonged antibiotic therapy) [p<0.001]. Gram-positive cases where the catheter was preserved corresponded to three cases of coagulase-negative Staphylococcus and one case with anatomical difficulties hindering alternative vascular access.

Out of the 52 patients, 10 experienced more than one episode of bacteremia during the study period. No statistically significant differences were found in their baseline characteristics or the etiological agent.

3.3. Evolution of Incidence Over the Study Period

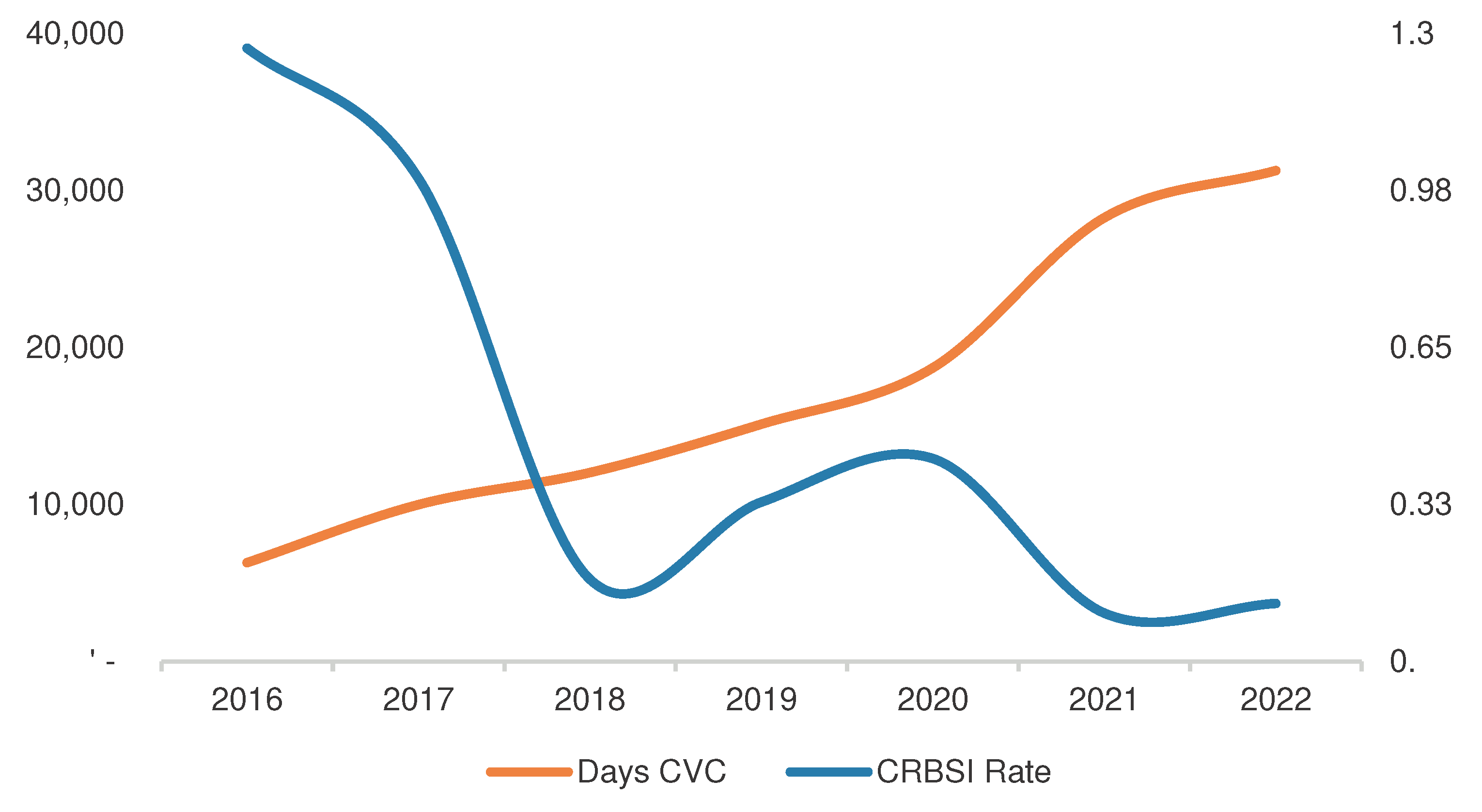

The graphical representation in

Figure 1 illustrates the trend in both catheter exposure days and bacteremia incidence throughout the study years.

As depicted, there is a notable decrease in bacteremia incidence since 2017, coinciding with the introduction of Tauro-LockTM heparin and the implementation of the taurolidine sealing protocol in 2018. This decline is statistically significant when compared to previous years (

Table 3).

Simultaneously, there is an observed increase in catheter exposure days over the study period. Despite a slight uptick in bacteremia incidence in 2020, the overall trend indicates a lower incidence rate, and there is no statistically significant reduction in the post-pandemic years (

Table 3).

4. Discussion

Bacteremia associated with central venous catheters remains a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in our hemodialysis patients. Over the 10-year study period, a total of 466 catheters were implanted in 426 patients in our hospital unit. Among the 588 patients who initiated hemodialysis during this period, only 162 patients (27.5%) were never carriers of a catheter at any point in their treatment. In recent years, especially since the 2020 pandemic, there has been a notable increase in the use of catheters as the definitive vascular access; in 2021, 69.6% of prevalent hemodialysis patients had central venous catheters (CVC). This figure is higher than reported in other registries. In the United States, up to 80% initiate hemodialysis via CVC, but only 15% of prevalent patients carry CVC [

5]. In Europe, approximately 50% initiate hemodialysis through CVC, and the prevalence varies among different countries (15-38%) [

9]. The increase in catheter use in our center could be attributed to two reasons: the aging population, leading to more lenient criteria for dialysis initiation with older and more comorbid incident patients, and the choice of vascular access depending not only on patient profile but also on the availability of vascular surgery teams. During the pandemic, there was a decrease in surgeries and, consequently, fewer arteriovenous fistulas were created.

Despite the increase in catheter use, the overall incidence rate over the ten-year study period was 0.52 episodes of bacteremia per 1000 catheter days. This rate is lower than reported in some large series [

1,

2] and similar to a recent national study where an incidence of 0.4 episodes per 1000 catheter days was recorded over a 14-year observational period [

10]. About 26% of these cases were early infections, defined as those occurring in the first thirty days of catheter insertion. The summer season significantly recorded more episodes, a phenomenon also described in other studies. This could be justified by the hypothesis that higher temperature and humidity conditions facilitate microbial adherence and biofilm formation [

8,

11]. Another explanation could be the seasonality of summer contracts, with less experienced nursing staff.

Gram-positive microorganisms were responsible for approximately 70% of the cases, consistent with literature reports [

1,

12,

13,

14,

15]. This percentage increased to 94% in cases of early infection. Coagulase-positive Staphylococcus aureus accounted for 85% of these cases and half of the total isolates (50.7%). Previous studies have shown a higher number of metastatic complications and mortality in bacteremias caused by Gram-positive bacteria, especially Staphylococcus aureus [

12,

16]. This is attributed to their greater capacity to create biofilms and adhere to native tissues [

17,

18]. However, it is a controversial issue, as other studies report worse outcomes (septic shock, septic complications, and ICU admissions) in Gram-negative bacteremias due to the tendency to preserve the catheter in these cases [

19,

20]. In our study, there was an overall low number of ICU admissions and complications, as well as an absence of mortality directly caused by bacteremia. We believe that following reference guidelines with the policy of early withdrawal in more aggressive germs (Gram-positive) or slow progression could play an important role in these results.

Throughout the study period, there was a decrease in the annual incidence of bacteremias despite a progressive increase in catheter exposure days. This difference became statistically significant from 2017 onwards. In 2018, a new catheter sealing protocol was implemented following the introduction of Tauro-LockTM heparin. Taurolidine is an antimicrobial that has been shown to significantly reduce the incidence of catheter-related sepsis [

21]. Therefore, these findings suggest a potential association between the introduced sealing protocols and the decline in bacteremia incidence. Further analysis may be warranted to explore the specific factors contributing to this trend and assess the long-term effectiveness of the implemented measures.

Recent studies have demonstrated a decrease in catheter-related bacteremias coinciding with the implementation of airborne transmission preventive measures imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic. An observational study conducted in two hospitals in one of the most affected European regions (Lombardy, Italy) showed a 90% reduction in catheter-related bacteremia incidence rates during the peak of the pandemic (February-May 2020) compared to the same period in the previous year (February-March 2019) [

7]. Another American study demonstrated a decrease in antibiotic administration in dialysis and specific admissions for catheter-related bacteremia from March 2020 onwards [

8]. In our center, despite maintaining a low incidence rate in the years after the pandemic, we cannot conclusively state a significant decrease. This might be because our hygiene measures before the pandemic already included device sterilization, the use of sterile gloves by nursing staff, and the use of surgical masks by both nursing staff and patients

5. Conclusions

The overall incidence of bacteremias is low compared to other results reported in the literature, despite having a significant number of catheters in our unit. The most frequently isolated microorganism was methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus. Early catheter removal, especially in Gram-positive infections, results in a low number of ICU admissions and septic complications, endorsing the protocol used. The summer period had the highest number of episodes. There seems to be a significant decrease in the annual incidence since 2017, coinciding with the implementation of a catheter sealing protocol with taurolidine. We did not find a clear decrease in the incidence of bacteremia in the years following the pandemic.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Allon, M. Dialysis catheter-related bacteremia: Treatment and prophylaxis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004, 44, 779–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin K, Poy Lorenzo YS, Mia Leung PY, Chung S, O’flaherty E, Barket N, Ierino F. Clinical outcomes and risk factors for tunneled hemodialysis catheter-related bloodstream infections. OFID 2020, 7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibeas J et al. Guía Clínica española de acceso vascular para hemodiálisis. NEFROLOGÍA. 2017, 37, 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Lok C.E. et al. KDOQI Clinical Practice Guideline for Vascular Access. Am J Kidney Dis. 2019, 75.

- United States Renal Data System: 2020 USRDS Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United Stated, bETHESTA, md, national Institutes od Health, National Institute os Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2020.

- Mokrzycki MH, Zhang M, Golestaneh L, Laut J, O Rosenberg S. An interventional controlled trial comparing 2 management models for treatment of tunneled cuffed catheter bacteremia: A collabo-rative team model versus usual physician-managed care. Am J Kidney Dis 2006, 48, 587-59. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidempergher M, Sabiu G, Orani MA, Tripepi G, Gallieni M. Targeting covid-19 prevention in hemodialysis, facilities is associated with a drastic reduction In central venous catheter-related in-fections. Journal of Nephrology 2021, 34, 345-35. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansen KL, Gilberston DT, Wetmore JB, Peng Y, Liu J, Winhandi ED. Catheter-associated bloodstream infections among patients on hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2022, 17, 429-433. [CrossRef]

- Pisoni RL, Zepel L, Port FK, Robinson BM. Trends in US vascular access use, patient preferences, and related practices: An update from the US Dopps Practice Monitor with international compari-sons. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015, 65, 905-91. [CrossRef]

- Almenara-Tejederas M, Rodríguez-Pérez MA, Moyano-Franco MJ, de Cueto-López M, Rodrí-guez-Baño J, Salgueira-Lazo M. Tunneled catheter-related bacteremia in hemodialysis patients: In-cidencia, risk factors and outcomes. A 14-year observational study. Journal of Nephrology. 2022, 36, 203.21. [CrossRef]

- Lok CE, Thumma JR, McCullough KP, Gillespie BW, Fluck RJ, Marshall MR, Kawanishi H, Ro-binson BM, Pisoni RL. Catheter-related infection and septicemia: Impact of seasonality and modifi-able practices from the Dopps. Semin Dial 2013, 27, 72–77. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrington CA, Allon M. Complications of hemodialysis catheter bloodstream infections: Impact of infecting organism. Am J Nephrol. 2019, 50, 126-132. [CrossRef]

- Marr KA, Sexton DJ, Conlon PJ, Corey GR, Schwab SJ, Kirkland KB. Catheter-related bactere-mia and outcome of attempted catheter salvage in patients undergoing hemodialysis. Ann Intern Med. 1997, 127, 27. [CrossRef]

- Beathard, GA. Beathard GA. Management of bacteremia associated with tunneled-cuffed hemodialysis cathe-ters. JASN. 1999; 10(5): 1045-1049.

- Phillips J, Chan DT, Swaminathan R, Patankar K, Boudville N, Lim WH. Haemodialysis vascular catheter-related blood stream infection: Organism types and clinical outcomes. Nephrology. 2023, 28, 249-253. [CrossRef]

- Maya ID, Carlton D, Estrada E, Allon M. Treatment of dialysis catheter-related Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia with an antibiotic lock: A quality improvement report. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007, 50, 289-295. [CrossRef]

- Costerson JW, Stewart PS, Greenberg EP. Bacterial biofilms: A common cause of persistent infection. Science. 1999, 284, 1318-132. [CrossRef]

- Paharik AE, Horswill AR. The staphylococcal biofilm: Adhesins, regulation, and host response. Microbiol Spectr. 2016, 4. Microbiol Spectr. [CrossRef]

- Shahar S, Mustafar R, Kamaruzaman L, Periyasamy P, Pau KB, Ramli R. Catheter-related bloodstream infections and catheter colonization among haemodialysis patients: Prevalence, risk factors and outcomes. Int J Nephrol. 2021, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Abe R, Oda S, Sadahiro T, Nakamura M, Hirayama Y, Tateishi Y, Shinozaki K, Hirasawa H. Gram-negative bacteremia induces greater magnitude of inflammatory responde than gram-positive bacteremia. Cria Care. 2010, 14, R27.

- González R, Redondo MC, Caro I, Ojeda MD, García AM, Huerga MC, Gómez M, Molina MC, García S, Fernández R, Canovas Y. Estudio de la eficacia del sellado con taurolidina y nitrato 4% para hemodiálisis en la prevención de infección y trombosis. Enferm Nefro. 2014, 17, 22.27. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).