1. Introduction

Musculoskeletal pain (MP) represents a non-negligible global issue affecting more than 30% of global population [

1]. It causes functional disability and emotional distress, thus conditioning a worsening in patients’ quality of life [

2]. There’s not a single recognized cause of MP, but it may be determined either by tissue damages, sensitization, functional dysfunctions or by undeterminable cause. Despite the high social burden related to MP, it remains an underestimated problem; being such a multifaceted symptom or clinical presentation, clinicians from very different backgrounds are confronted with MP in its various forms, therefore it is not surprising that no consensus about its management has been reached so far [

3].

2. Heat Therapy Overview

2.1. Mechanism of Action

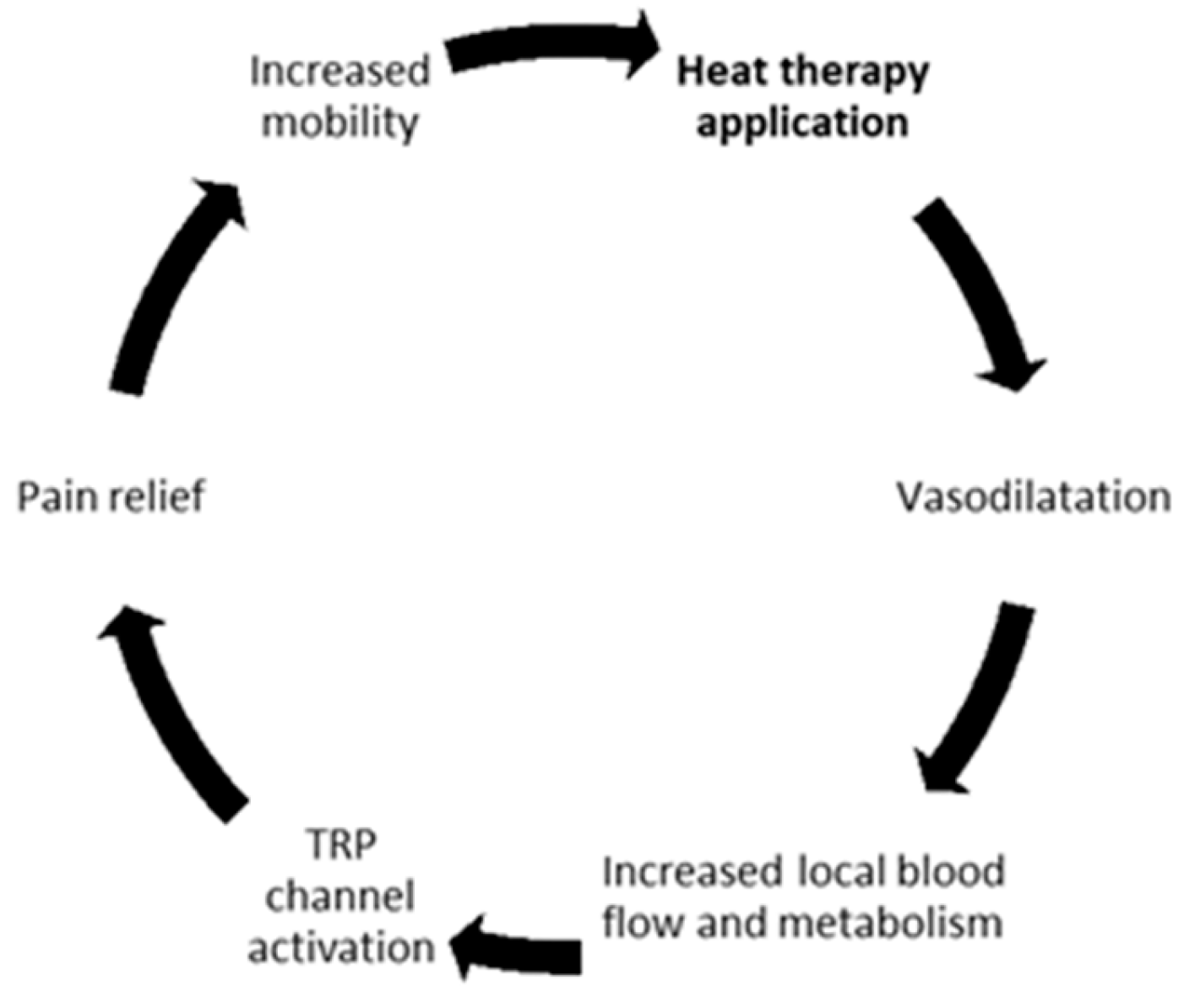

HT represents one of the most ancient nonpharmacological pain treatments. It increases the temperature of a specific body area thanks to the application of an external medium of heat. Among the recognized effects of heat on tissues can be listed: vasodilatation, increased blood flow, metabolism, and function activation of transient receptor potential (TRP) channel and pain relief [

4] (

Figure 1).

The analgesic effects of heat are partly mediated by TRP membrane channels [

5]. The TRP vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) receptors help in heat neural transduction; through their engagement, anti-nociceptive pathways in central nervous system are activated and they cause a reduction in muscle tonicity helping their relaxation, thereby reducing MP and increasing muscle flexibility [

6].

Moreover, it is well known that an increasing of 1°C in tissue temperature can cause a 10–15% increase in the local metabolism [

7]. Thus, HT play an important role in tissue healing and regeneration by increasing catabolic and anabolic pathways.

Kim and colleagues performed a study to assess the effects of repetitive exposure to local HT on skeletal muscle function, capillarization, myofiber morphology and mitochondrial content. In a sample of 12 young adults, they demonstrated that local HT applied on the vastus lateralis muscle for 8 weeks promoted a proangiogenic environment and increased muscle strength, without affecting mitochondrial content [

8].

2.2. Clinical Applications

HT is a widely adopted approach for MP, with evidence about its efficacy reported for both general and non-specific condition such as spinal (low back and neck), knee and wrist pain and highly specific clinical condition such as delayed-onset muscle soreness (DOMS) [

9,

10].

For example, Petrofsky and colleagues [

11] performed a randomized clinical trial to assess whether the addition at home of low-level continuous heat (LLCH, i.e. commercially available heat packs to be applied 6 hours before they performed their home exercise) and/or ibuprofen to physical therapy sessions could improve the outcomes of people with chronic neck pain. They demonstrated that both LLCH and ibuprofen were effective in reducing neck pain and enhancing the neck mobility.

However, as HT is probably considered a self-management strategy rather than a treatment by many (see for example the 2018 update of the EULAR document about hand osteoarthritis, also a source of MP [

12]), or not part of “core” non-pharmacological treatment [

13], evidence about its use is probably underreported. Recently, to better address the role of HT in the treatment of MP, a panel of experts developed a list of 54 statements concerning mechanism of action, efficacy, and safety of HT to be disseminated through a survey to 116 European experts [

14]. The panellists were asked to use a 5-point scale to agree or disagree with the proposed statements and a threshold of 66% was set to reach the consensus. The Delphi consensus was obtained for 78% of prespecified items and the most robust were mechanism of action of heat on muscle, the indication in chronic MP, its effectiveness as part of a multimodal approach to MP and the safety and tolerability of superficial HT [

14].

2.3. Application Modalities

Superficial heat penetration is usually less than 1 cm, while the use of deep heat penetration is up to about 3-5 cm [

15]. There are mainly three different mechanisms thorough which HT can be delivered: conduction, conversion, and convection. Conduction is the transfer of heat between two objects at different temperature through direct contact and it’s the way through which hot packs, patches, wraps and paraffin bath work. Conversion is the transfer of heat through changing from one energy form into another (i.e., ultrasound and radiant heat). Another possible way of delivering heat is convection that consist of transferring heat by fluid circulation (liquid or gas) over the surface of a body (i.e., hydrotherapy) [

9].

Many familiar ways of administering heat have been traditionally used in home settings. The prescription of applying heat might translate in different modalities in every household, depending also on cultural habits and geographic location. Our panel underlined that standardizing heat administration with commercially available devices, while “medicalizing” a simple therapeutic approach, could also help compliance and evaluation of the effectiveness of heat therapy in clinical settings.

2.4. Safety

The Delphi consensus also provided indications on safety concerns regarding HT based on heat wraps [

14]. According to the results, caution should be executed in patients with active immune diseases, cancer, active osteoarthritis, neurological diseases, zoster infections, skin injuries/conditions and circulation defects as candidates for superficial HT based on heat wraps. Moreover, skin integrity represents a non-negligible criterion in selecting potential candidates to HT [

14].

Reassuringly, no deaths and no serious adverse events have been reported so far for superficial heat therapy based on heat wraps. Mild heat-related skin adverse events were reported including redness/pinkness, and first/second degree burns. All the skin effects related to thermal injury were infrequent, mild-to-moderate, and independently recovered [

16]. Overall, application of heat wraps for superficial HT can be considered safe. During the discussion some members of the panel hypothesized that, after taking into account possible allergies to other components (e.g. glue in adhesive patches), standardized devices could help reduce heat related local adverse events, especially in less diligent patients.

2.5. Heat Therapy versus Cold Therapy, Which and When

Clinical members of the panel reported a frequent question posed by patients, regarding the relative role of heat and cold therapy (CT) in dealing with their MP. Therefore, some considerations resulting from the literature review will be recapped hereafter.

CT has been generally accepted to reduce inflammation process, perfusion, swelling, tissue damage and pain for many years [

17]. The common ways of delivering CT include cold water immersion, cold packs, cold air exposure and ice massage. The application of cold therapy decreases tissue temperature while reducing blood flow and microvascular perfusion through vasoconstriction and pain relief through slowing sensory nerve conduction velocity [

18].

When choosing between HT and CT the phases of the healing process including the inflammatory phase, the proliferation phase and the remodelling phase should be considered. The first phase can last for 1 to 3 days, varying based on injury severity, and is determined by pro-inflammatory mechanism to clean up the damaged area as well as to create the basis for cellular process of regeneration [

19]. During this phase, cold therapy can help to limit inflammatory process and pain. During the second phase, new tissue and scar tissue are formed based on cell activation, angiogenesis, and extracellular matrix (ECM) formation. Heat can be applied to the injured area to facilitate the healing process [

6,

20]. The third phase is the process of returning to health: the restoration of structure and function of injured or diseased tissues. In this phase, the blood supply is restored by the release of angiogenic factors, plus the restoration of structural tissue integrity, the extracellular matrix, and the neuronal innervation of the injured muscle fibres. Here, heat therapy can improve the release of myogenic growth factors [

21].

As a broad guideline, CT is mainly applied in acute and/or traumatic conditions and in case of chronic damage with predominant active inflammation (i.e., during the initial 48 to 72 hours after an acute injury) [

22], while HT should be applied once the inflammatory phase is recovered [

23].

Nevertheless, most recommendations for the application in clinical practice of heat and cold therapy are based on empirical experience and “good clinical practice” and there is a lack of powered, high-quality randomized clinical trials. In addition, many patients apply superficial HT or CT irrespective of scientific rationale or healthcare professional advice, it is crucial to better address the correct indications and contraindications of these two methods.

2.6. Specific Applications of Heat Therapy

After this general overview of basic notions and clinical uses of HT, the rest of the paper will be aimed at narratively reviewing the literature regarding potential HT applications, focusing specifically on knee pain and sport activities.

3. Heat Therapy and Knee Pain

3.1. Knee Pain as a Multifaceted Clinical Condition

Knee pain (KP) is a common clinical condition related with traumatic, overuse or degenerative injuries with range of presentations that varies from acute to chronic pain. Among possible anatomic structures causing KP there are intraarticular structures, and surrounding tendons, bones, ligaments, and muscles [

24]. Joint pain is the most common joint symptom in the world, with an age-related increase in both incidence and prevalence [

25].

Knee injuries are very frequent among athletes [

26] and general population [

27], and inevitably a major source of possible KP. Non-traumatic knee pain is mainly caused by osteoarthritis (OA) and results from breakdown of the articular cartilage, causing stiffness, pain, redness, heat, joint swelling, and decreased range of motion (ROM); the knee is one of the most frequently involved joints in OA. Typically pain or stiffness in the joint occurs after periods of inactivity (inflammatory pain) or excessive use (mechanical pain) [

28]. Symptoms of OA usually progress slowly over years, occurring initially after exercise and becoming constant over time, also interfering with normal daily activities and Quality of life (QoL) [

28].

Tendon and ligament dysfunction can also be responsible for KP occurrence. Overload, disrepair and structural damages of these structures are the most common causes of pain [

29].

A myofascial trigger point is a hyperirritable spot, usually within a taut band of skeletal muscle, which is painful on compression and can give rise to characteristic referred pain, motor dysfunction, and autonomic phenomena [

30]. Thus, the origin of KP can also be the muscle and trigger point related KP has been widely described [

31].

Another common cause of KP is patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS) and Iliotibial band syndrome (ITBS) that causes anterior or lateral knee-pain respectively. Typical symptoms include pain behind or around the patella or on the lateral border of the knee that increases with running and activities that involve knee flexion and may worsening after a period of rest [

32,

33,

34].

3.2. Heat Therapy for the Management of Knee Pain

Both HT and CT are recommended as non-invasive and non-pharmacological treatments for musculoskeletal pain by different international guidelines, including Canadian and American College of Rheumatology ones [

35,

36]. Other institutions choose not to include thermal modalities in their recommendations since they were not considered “core” treatments, as we discussed above [

13].

Petrofsky and colleagues [

37] performed a randomized controlled trial to assess whether the use of low level of continuous heat (LLCH) can improve knee pain recovery when added to physical therapy in patients with chronic knee pain. Fifty patients were randomly allocated to experimental or placebo arm. All enrolled patients received both conventional physical therapy and they were asked to perform therapeutic exercise at home each day between sessions. In adjunction patients allocated in the experimental arm applied LLCH knee wraps for 6 hours at home before home exercises. The LLCH group showed a significant pain attenuation compared to the placebo group and patients in the experimental arm showed a significantly higher home exercise compliance.

Kim and colleagues [

38], evaluated in a randomized controlled trial the effects of adding HT to exercise in the management of elderly women’s chronic KP. One hundred and fifty women over 75 years-old complaining of knee pain were randomly allocated to receive either physical therapy plus HT, physical therapy alone, HT alone or health education. The results showed a visual analogue scale (VAS) improvement in patients treated with HT, both alone and combined with exercise. The total Japanese knee osteoarthritis measure (JKOM) score, muscle strength, and functional mobility significantly improved in the group of patients that received the combination of HT and physical therapy. According to study results, when combined with exercise HT seems to help in reducing pain, improving physical function, and increasing patient’s quality of life.

The effects of HT in the management of KP were investigated in another clinical trial conducted on eighteen women aged between 50 and 69 years old. Patients were randomly assigned to a 12-week intervention with HT alone or exercise alone and the resulting effects were evaluating using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) T2 mapping. Local HT applied with a standardised method and evaluated after 12 weeks improved patients’ clinical scores (Japanese Knee Osteoarthritis Measure) and MRI measurements of cartilage thickness [

39].

3.3. Heat versus Cold Therapy in Knee Pain

So far there is only sparse evidence in the literature regarding the use of either HT or CT in the management of KP. Therefore, it is crucial to highlight the role of these two different approaches and define the correct sequence of application.

In a trial comparing the effect of HT and CT on pain and joint function in knee OA, 117 patients were randomly allocated to receive CT, HT, or placebo control. Both CT and HT proved to be significantly effective in reducing pain and improving joint function when compared to placebo [

40].

Aciksoz and colleagues [

41], in a randomized controlled trial, investigated the effect of superficial cold and heat applications on pain, functional status and quality of life in 96 cases of knee OA. In the 2 experimental groups patients received on top of standard orthopaedic treatment either superficial HT or CT. Both therapies were applied 20 min 2 times a day, in the morning and in the evening, for 3 weeks. Both heat and cold superficial applications determined a mild improvement in pain, functional status, and quality of life. However, no significant differences were found between the two interventional groups.

Moreover, the possible treatment sequence of applying HT followed by CT to improve passive knee flexion was evaluated in subjects with restricted knee motion. Seventy-one subjects were randomized to receive either HT-CT sequential treatment or HT alone. Interestingly, statistically limited but significant increments of knee flexion were observed for subject receiving the sequential approach [

42].

4. Heat Therapy and Sport

Performing sports is one of the main recommendations for a healthy lifestyle both in children [

43] and in the elderly [

44,

45]. Although health benefits of sports normally outweigh the risks, it is estimated that one out of three working adults lost at least one day of work a year due to a sport-related injury [

46,

47].

Warm up by increasing tissue temperature is recognised as an effective method to increase tissue distensibility and reduce the incidence of injury [

48,

49,

50]. Among possible warm-ups modalities are active treatments as exercise to increase circulation and metabolism, myofascial treatments as stretching or foam rolling, passive interventions as heat application or massage, or even mental conditioning [

49,

50,

51,

52].

However, it remains unclear which factors can reduce the risk of sports-related injuries, and which can be the best prevention management.

4.1. Heat Therapy Application in Sport

Empirically, HT is very commonly used before exercise. In addition, basic science studies showed that the increased tissues metabolism due to local heating helps in preparing muscles for athletic performance [

48,

53,

54]. Moreover, HT is capable to promote recovery after exercise thanks to the possibly increased removal of metabolism products, increasing the delivery of nutrients and glycogen resynthesis and promote healing pathways [

55,

56].

One of the most interesting applications of superficial HT in sport is represented by the increased joint flexibility after heat application. This effect of HT can play a crucial role in reducing both the chance of injury and the energy cost of muscle contraction [

54].

Some

in vivo studies on animal models provided insights on the rationale of using HT in sport activities. In rat tendon models, when increasing tissue temperature and maintaining it before applying force caused significantly less damage. Also, at elevated temperatures the lower loads applied for prolonged periods produced significantly greater residual elongation [

57].

A trial performed on twenty-two female collegiate lacrosse and soccer athletes showed that HT improved the hip ROM. Interestingly, the trial highlighted how athlete perception is not always reliable and professionals should evaluate and prescribe treatment on a case-by-case basis [

58].

In a systematic review on the effects of stretch with or without HT on ROM, twelve studies including 352 participants were retrieved. The subgroup analyses demonstrated a greater improved ROM after heat combined with stretch, compared to HT alone. However, subgroup analysis of muscle groups and different HT delivering methods didn’t show significant differences [

59].

It remains unclear whether superficial HT can be used at different timing of sport activity, such as during the performance to enhance it. Future research should confirm these observations.

4.2. Heat versus Cold Therapy in Sport

As abovementioned for KP management, the possibility of combining, sequencing, or switching HT and CT in sport represents an interesting and debated topic.

Twenty subjects of both sexes were enrolled in a trial designed to determine if HT would increase extensibility of the anterior and posterior knee cruciate ligaments and reduce the force needed to flex the joint. Results proved that HT increased ligaments flexibility and the force needed to flex the knee was reduced by 25% when compared to CT [

60].

In a systematic review and meta-analysis of 32 randomized controlled trials on the effect of HT and CT proved that CT could reduce DOMS within 1 hour after exercise. Otherwise, HT could reduce the pain of patients within and over 24 hours [

10].

Moreover, a network metanalysis, reported that within 24 and 48 hours postexercise, hot packs application was superior to other interventions, whereas over 48 hours, CT was the optimal intervention for pain relief in patients with DOMS. Authors underlined that HT had a better safety and convenience profile [

61].

5. Discussion

Musculoskeletal pain represents a global health issue with medical implications Patients with MP are seen in many different specialised settings, but very often in general medicine and even by different health professionals. Despite its frequency, the study of its prevention and treatment is complicated by the fact that it does not recognize a specific and unique aetiology.

Reviewing the basic science presented, the expert panel agreed that superficial heat therapy – through increasing tissues temperatures – can enhance local metabolism and function and thus relieve pain.

The evidence gathered for this narrative review, though sparse and partial, in the opinion of the experts involved, showed HT to be a potentially useful, safe, and cost-effective tool in many types of musculoskeletal pain, specifically in knee pain and sport activities related MP, which represent two of the most intriguing field of application and research for the use of superficial HT.

HT alone or in combination with other treatments has been found to be beneficial in the management of KP conditions in 3 domains: pain relief, promotion of healing and return to normal function and activity. On the other hand, HT can play a role in sport both before and after exercise. Before performing sports, HT might help in preparing muscles for athletic performance. After performing physical activity, it could promote recovery and healing pathways. Both methods of HT delivery may have implications in injury prevention and pain reduction.

Despite being an ancient therapeutical approach and therefore often regarded rather as a self-management strategy, it is the opinion of this panel that HT deserves attention in clinical research and practice guidelines, as a part of a multimodal and multidisciplinary approaches to MP. Moreover, combining and sequencing superficial heat and cold therapy represent an interesting topic of study.

Future research should be aimed both at investigating the role of HT in preventing or treating MP as a clinical symptom in a general setting and as a part of more specific underlying diagnoses in the different medical specialties involved. Randomized controlled trials to evaluate the efficacy and safety of HT in different populations -should use appropriate validated outcome measures and could benefit of providing HT through standardised methods which should improve repeatability, compliance, safety, and external validity. Practicing clinicians and guidelines should consider HT.

4. Materials and Methods

An expert panel of clinicians and researchers representing different medical specialties and from several European countries was gathered to discuss the potential role of superficial heat therapy (HT) in conditions which present with some degree of MP. Nine experts on MP, including one orthopedist, one sports medicine physician, two family medicine physicians, one physiotherapist, two physiatrists, and one exercise physiologist were selected based on their previous experience in heat therapy.

After one virtual meeting and both personal and centralised literature reviews, the expert panel decided to produce a narrative review to summarize the knowledge regarding the application of heat therapy in preventing and treating MP, with special focus on knee pain (KP) and sport activities.

Results of the information collected, and the opinions expressed will be summarised in this paper, starting from a general overview of what is known about heat therapy and its possible mechanism of action, its clinical application and safety issues, its role in comparison or in combination with cold therapy, and then proceeding by summarising the evidence related to KP and sport activities. This study, as a literature review, is exempt from Institutional Review Board approval.

Author Contributions

All the authors equally contributed to conceptualization; methodology, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, and supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Angelini sponsored the expert meeting from which this manuscript arose. Angelini also supported financially Ethos srl which supported the authors in the preparation of the manuscript. This has not impacted the content of the manuscript.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

In this paper no new data were created.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Dr. Cristina Gurizzan for medical writing support.

Conflicts of Interest

“GZ has received honorarium for consultancy/advisory board for Angelini Pharma, support for attending meetings from Orthotech and Jtech, and honorarium for participation on an Advisory Board from Vivanka. IAC reports personal fees from Éthos S.r.l, during the conduct of the study. MA has nothing to disclose. IG has nothing to disclose. TH has received consulting fees from Angelini Pharma and Ethos S.r.l. GI has nothing to disclose. KK has nothing to disclose. GRM reports personal fees from Ethos s.r.l, during the conduct of the study.The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results”.

References

- Vos T, Lim SS, Abbafati C et al, Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 2019, 396, 1204–1222.

- Puntillo F, Giglio M, Paladini A, et al, Pathophysiology of musculoskeletal pain: a narrative review. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis 2021, 13, 1759720X2199506. [CrossRef]

- Blyth FM, Briggs AM, Schneider CH, et al, The Global Burden of Musculoskeletal Pain—Where to From Here? Am J Public Health 2019, 109, 35–40. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papaioannou TG, Karamanou M, Protogerou AD, Tousoulis D, Heat therapy: an ancient concept re-examined in the era of advanced biomedical technologies. J Physiol 2016, 594, 7141–7142. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brederson JD, Kym PR, Szallasi A, Targeting TRP channels for pain relief. Eur J Pharmacol 2013, 716, 61–76. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadler SF, Weingand K, Kruse RJ, The physiologic basis and clinical applications of cryotherapy and thermotherapy for the pain practitioner. Pain Physician 2004, 7, 395–399.

- Ravindranath G, Physical agent in Rehabilitation from Research to Practice. Med J Armed Forces India 2004, 60, 413. [CrossRef]

- Kim K, Reid BA, Casey CA, et al, Effects of repeated local heat therapy on skeletal muscle structure and function in humans. J Appl Physiol 2020, 128, 483–492. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freiwald J, Magni A, Fanlo-Mazas P, et al, A Role for Superficial Heat Therapy in the Management of Non-Specific, Mild-to-Moderate Low Back Pain in Current Clinical Practice: A Narrative Review. Life 2021, 11, 780. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Li S, Zhang Y, et al, Heat and cold therapy reduce pain in patients with delayed onset muscle soreness: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 32 randomized controlled trials. Phys Ther Sport 2021, 48, 177–187. [CrossRef]

- Petrofsky JS, Laymon M, Alshammari F, et al, Use of low level of continuous heat and Ibuprofen as an adjunct to physical therapy improves pain relief, range of motion and the compliance for home exercise in patients with nonspecific neck pain: A randomized controlled trial. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil 2017, 30, 889–896.

- Kloppenburg M, Kroon FP, Blanco FJ, et al, 2018 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of hand osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2019, 78, 16–24. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes L, Hagen KB, Bijlsma JWJ, et al, EULAR recommendations for the non-pharmacological core management of hip and knee osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2013, 72, 1125–1135. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lubrano E, Mazas PF, Freiwald J, et al, An International Multidisciplinary Delphi-Based Consensus on Heat Therapy in Musculoskeletal Pain. Pain Ther 2023, 12, 93–110. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen W-S, Annaswamy TM, Yang W, et al, Physical Agent Modalities. In: Braddom’s Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. Elsevier, 2021. 338-363.e6.

- Nadler SF, Steiner DJ, Erasala GN, et al, Continuous low-level heatwrap therapy for treating acute nonspecific low back pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2003, 84, 329–334. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allan R, Malone J, Alexander J, et al, Cold for centuries: a brief history of cryotherapies to improve health, injury and post-exercise recovery. Eur J Appl Physiol 2022, 122, 1153–1162. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwiecien SY, McHugh MP, The cold truth: the role of cryotherapy in the treatment of injury and recovery from exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol 2021, 121, 2125–2142. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forcina L, Cosentino M, Musarò A, Mechanisms Regulating Muscle Regeneration: Insights into the Interrelated and Time-Dependent Phases of Tissue Healing. Cells 2020, 9, 1297. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lohman III EB, Sackiriyas KSB, Bains GS, et al, A comparison of whole body vibration and moist heat on lower extremity skin temperature and skin blood flow in healthy older individuals. Med Sci Monit 2012, 18, CR415–CR424.

- Kim WS, Kim J, Exploring the impact of temporal heat stress on skeletal muscle hypertrophy in bovine myocytes. J Therm Biol 2023, 117, 103684.

- Sluka KA, Christy MR, Peterson WL, et al, Reduction of pain-related behaviors with either cold or heat treatment in an animal model of acute arthritis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1999, 80, 313–317. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hotfiel T, Hoppe MW, Heiss R, et al, Quantifiable Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound Explores the Role of Protection, Rest, Ice (Cryotherapy), Compression and Elevation (PRICE) Therapy on Microvascular Blood Flow. Ultrasound Med Biol 2021, 47, 1269–1278. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadler NM, Knee pain is the malady--not osteoarthritis. Ann Intern Med 1992, 116, 598–9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandl LA, Osteoarthritis year in review 2018: clinical. Osteoarthr Cartil 2019, 27, 359–364. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kujala UM, Taimela S, Antti-Poika I, et al, Acute injuries in soccer, ice hockey, volleyball, basketball, judo, and karate: analysis of national registry data. BMJ 1995, 311, 1465–1468. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gage BE, McIlvain NM, Collins CL, et al, Epidemiology of 6.6 Million Knee Injuries Presenting to United States Emergency Departments From 1999 Through 2008. Acad Emerg Med 2012, 19, 378–385. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter DJ, McDougall JJ, Keefe FJ, The Symptoms of Osteoarthritis and the Genesis of Pain. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2008, 34, 623–643. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madi S, Acharya K, Pandey V, Current concepts on management of medial and posteromedial knee injuries. J Clin Orthop Trauma 2022, 27, 101807. [CrossRef]

- Lavelle ED, Lavelle W, Smith HS, Myofascial trigger points Anesthesiol Clin. 2007, 4, 841–51. [CrossRef]

- Rahou-El-Bachiri Y, Navarro-Santana MJ, Gómez-Chiguano GF, Effects of Trigger Point Dry Needling for the Management of Knee Pain Syndromes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Med 2020, 9, 2044. [CrossRef]

- Gaitonde DY, Ericksen A, Robbins RC, Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome. Am Fam Physician 2019, 99, 88–94.

- D’Ambrosi R, Meena A, Raj A, et al, Anterior Knee Pain: State of the Art. Sport Med - Open 2022, 8, 98. [CrossRef]

- Strauss EJ, Kim S, Calcei JG, Park D, Iliotibial band syndrome: evaluation and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2011, 19, 728–736. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, Forciea MA, Noninvasive Treatments for Acute, Subacute, and Chronic Low Back Pain: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med 2017, 166, 514. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hochberg MC, Altman RD, April KT, et al, American College of Rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012, 64, 465–474. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrofsky JS, Laymon MS, Alshammari FS, Lee H, Use of Low Level of Continuous Heat as an Adjunct to Physical Therapy Improves Knee Pain Recovery and the Compliance for Home Exercise in Patients With Chronic Knee Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Strength Cond Res 2016, 30, 3107–3115. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim H, Suzuki T, Saito K, et al, Effectiveness of exercise with or without thermal therapy for community-dwelling elderly Japanese women with non-specific knee pain: A randomized controlled trial. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2013, 57, 352–359. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochiai S, Watanabe A, Oda H, Ikeda H, Effectiveness of Thermotherapy Using a Heat and Steam Generating Sheet for Cartilage in Knee Osteoarthritis. J Phys Ther Sci 2014, 26, 281–284. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ariana M, Afrasiabifar A, Najafi Doulatabad S, et al, The Effect of Local Heat Therapy versus Cold Rub Gel on Pain and Joint Functions in Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis. Clin Nurs Res 2022, 31, 1014–1022. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aciksoz S, Akyuz A, Tunay S, The effect of self-administered superficial local hot and cold application methods on pain, functional status and quality of life in primary knee osteoarthritis patients. J Clin Nurs 2017, 26, 5179–5190. [CrossRef]

- Lin YH, Effects of thermal therapy in improving the passive range of knee motion: comparison of cold and superficial heat applications. Clin Rehabil 2003, 17, 618–623. [CrossRef]

- Fathi Azar E, Mirzaie H, Jamshidian E, Hojati E, Effectiveness of perceptual-motor exercises and physical activity on the cognitive, motor, and academic skills of children with learning disorders: A systematic review. Child Care Health Dev. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Sharifi M, Nodehi D, Bazgir B, Physical activity and psychological adjustment among retirees: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 194.

- Malm C, Jakobsson J, Isaksson A, Physical Activity and Sports-Real Health Benefits: A Review with Insight into the Public Health of Sweden. Sports (Basel) 2019, 7, 127.

- Conn JM, Sports and recreation related injury episodes in the US population, 1997–1999. Inj Prev 2003, 9, 117–123.

- Emery CA, Pasanen K, Current trends in sport injury prevention. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2019, 33, 3–15. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasanen K, Parkkari J, Pasanen M, Kannus P, Effect of a neuromuscular warm-up programme on muscle power, balance, speed and agility: a randomised controlled study. Br J Sports Med 2009, 43, 1073–1078. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaBella CR, Huxford MR, Grissom J, et al, Effect of Neuromuscular Warm-up on Injuries in Female Soccer and Basketball Athletes in Urban Public High Schools. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2011, 165, 1033. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrofsky JS, Laymon M, Lee H, Effect of heat and cold on tendon flexibility and force to flex the human knee. Med Sci Monit 2013, 19, 661–667. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGowan CJ, Pyne DB, Thompson KG, Rattray B, Warm-Up Strategies for Sport and Exercise: Mechanisms and Applications. Sports Med 2015, 45, 1523–1246. [CrossRef]

- Bishop D, Warm up I: potential mechanisms and the effects of passive warm up on exercise performance. Sports Med 2003, 33, 439–454.

- Kim K, Monroe JC, Gavin TP, Roseguini BT, Local Heat Therapy to Accelerate Recovery After Exercise-Induced Muscle Damage. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 2020, 48, 163–169. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrofsky J, Laymon M, Alshammari F, et al, Continuous Low Level Heat Wraps; Faster Healing and Pain Relief during Rehabilitation for Back, Knee and Neck Injuries. World J Prev Med. 2015, 3, 61–72.

- Heinonen I, Brothers RM et al., Local heating, but not indirect whole body heating, increases human skeletal muscle blood flow. J Appl Physiol 2011, 111, 818–824. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fradkin AJ, Zazryn TR, Smoliga JM, Effects of warming-up on physical performance: a systematic review with meta-analysis. J Strength Cond Res 2010, 24, 140–148. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warren CG, Lehmann JF, Koblanski JN, Heat and stretch procedures: an evaluation using rat tail tendon. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1976, 57, 122–6.

- Oranchuk DJ, Flattery MR, Robinson TL, Superficial heat administration and foam rolling increase hamstring flexibility acutely; with amplifying effects. Phys Ther Sport 2019, 40, 213–217. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakano J, Yamabayashi C, Scott A, Reid WD, The effect of heat applied with stretch to increase range of motion: A systematic review. Phys Ther Sport 2012, 13, 180–188. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee H, Effect of heat and cold on tendon flexibility and force to flex the human knee. Med Sci Monit 2013, 19, 661–667. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Lu H, Li S, et al, Effect of cold and heat therapies on pain relief in patients with delayed onset muscle soreness: A network meta-analysis. J Rehabil Med 2022, 54, jrm00258. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).