Introduction

Premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) are recorded in up to 50% of healthy individuals undergoing 24 hours ECG ambulatory monitoring, with an increasing trend with aging [

1].

Several studies comparing PVC prevalence in healthy athletes and sedentary individuals showed that the prevalence of ventricular arrhythmias did not differ between these populations [

2] and it was unrelated to type, intensity and years of sport practice [

2,

3]. However, we also know that adolescents and young adults who participate in competitive sports have three times the risk of sudden cardiac death (SCD) compared to sedentary counterparts, and that ventricular arrhythmias, including PVCs, increase the risk of SCD during activity [

4,

5]. According to European and American guidelines, the assessment of PVCs requires specific evaluation with echocardiography, exercise testing and 24-hour ambulatory ECG monitoring, especially in athletes [

6,

7]. Cardiac Magnetic Resonance (CRM) with late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) is a second line exam and, to date, the most accurate test to exclude or confirm the presence of structural heart disease (SHD) when there is a suspicion of SHD missed by echocardiography [

8,

9]. A comprehensive invasive (electro-anatomical mapping) workup provided additional diagnostic elements and could improve the sports eligibility assessment of athletes presenting with ventricular arrhythmias [

10,

11,

12].

Several studies [

14,

15,

16] have shown that, in most athletes with no apparent SHD, PVCs originate most frequently from the right/left ventricular outflow tract (RVOT/LVOT) or from left fascicle. RVOT/LVOT and fascicular PVCs usually are not associated with echocardiographic/CMR structural heart disease and, during exercise testing, decrease or disappear at peak of exercise and reappear during recovery [

13]. Other PVC morphologies are uncommon in the athletes; the uncommon PVC morphologies are more frequently associated with LGE on CMR and may be associated with underlying SHD [

17].

The management of uncommon PVCs involves identifying the potential underlying structural heart disease and implementing appropriate treatment. Idiopathic PVCs can be addressed through both medical and ablative therapies.

Ablative approaches have demonstrated efficacy and safety and medical therapy is generally poorly tolerated by young athletes. Ablative approach it is recommended for individuals with symptomatic idiopathic PVCs and when high PVCs burden is associated with left ventricular dysfunction [

6].

Furthermore, infundibular and fascicular PVCs often restrict participation in competitive sports. Several studies indicate that ablative therapy, particularly for right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT) and fascicular PVCs, is superior to medical therapy [

4,

6,

18,

19,

20,

21]. Catheter ablation of PVCs appears to have a very good acute and long-term procedural success rate, with an overall low complication [

22]. However, there are no investigations about the outcomes of PVC catheter ablation (CA) in athletes compared to the sedentary population in patients without SHD and with PVCs of apparently benign morphology.

Materials and Methods

We conducted a prospective single-centre observational study to compare the efficacy and safety of radiofrequency CA of idiopathic benign morphology PVCs in athletes versus sedentary population without SHD. In addition, we aimed to evaluate the return to physical activity after the ablative treatment in the athlete group.

The study was performed respecting the institutional standards, national legal requirements, and Helsinki declaration for ethical standards. All patients received and signed written informed consent to the procedure.

Study Population

We enrolled 79 consecutive patients from January 2020 to October 2022 with a class I or IIa indication to PVC CA according to the current guidelines [

6].

According with the European recommendations, all patients had undergone medical examination, standard 12-lead ECG, echocardiography and maximal exercise testing. Further instrumental evaluations were decided on a clinical basis. CMR was performed in selected cases at the physicians' discretion.

Inclusion criteria were:

- -

age >18 years,

- -

>2000/24h PVCs at 24h ambulatory ECG monitoring,

- -

PVCs benign morphology (RVOT, LVOT, fascicular origin),

- -

preserved left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF).

Exclusion criteria were:

- -

previous PVCs catheter ablation,

- -

reduced LVEF (less than 50%),

- -

medical history of ischemic, hypertrophic and right ventricular arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy,

- -

medical history of myocarditis,

- -

family history of juvenile (<45 years) sudden death or hereditary cardiomyopathies,

- -

evidence of SHD at echocardiography or CMR,

- -

evidence of LGE in presumed PVCs area of origin at CMR.

Study Protocol (Design and Setting)

Only patients meeting the inclusion criteria were enrolled. The presumed origin of ventricular extrasystole, in relation to the characteristics on the 12-lead ECG, was assessed by two expert cardiologists. In the event of disagreement, a third cardiologist was consulted. A thorough history of physical activity and an accurate medical history were obtained.

Patients were divided into two groups: group 1, athletes (regularly performing physical activity); group 2, non-athletes (not performing regular physical activity). Subsequently, the group of athlete patients was further divided into agonist and leisure-time athletes.

Furthermore, the pre-ablation physical activity level of these patients was evaluated, including the intensity of their exercise and the type of sport they participated in, the number of weekly training session, the duration of weekly training hours and any limitations in physical activity due to PVCs.

All patients underwent 12-lead ECG, laboratory work-up and trans-thoracic echocardiogram. After obtaining written informed consent, all patients underwent radiofrequency CA.

Radiofrequency Catheter Ablation

All procedures in both athletes and non-athletes groups were performed by an expert electrophysiologist with at least a 10 years experience in PVCs CA.

No sedation or general anesthesia was performed at the beginning of the procedure, in order not to compromise the presence of PVCs. Conscious sedation with i.v. dexmedetomidine and fentanyl or simple analgesia with fentanyl was performed by operators’ discretion, after mapping.After ultrasound-guided femoral veins catheterization with Seldinger’s technique, ablation catheter and decapolar catheter for coronary sinus mapping were introduced; intracardiac echocardiography was used to the physician’s discretion.

For left-sided procedures, the retro-aortic approach was the first choice. Whenever necessary, the transseptal puncture was performed and then SL0 introducer replaced by the AgilisTM NxT steerable introducer. When it was necessary to access the left ventricle, before transseptal puncture/retro-aortic access, an unfractionated heparine (UFH) bolus of 100 IU/Kg was administered, then the UFH infusion was continued till the conclusion of the procedure maintaining an activated clotting time >300 sec.

In case of absent or infrequent PVCs at the time of CA, several methods were employed to induce them. First, intravenous infusion of isoprenaline was used. If this approach proved ineffective, a programmed atrial/ventricular pacing study was performed using up to three extrastimuli and burst pacing. As a last resort, i.v. caffeine infusion was employed as an alternative method. Pacemapping was also performed to assess if the QRS morphology at the earliest site of activation matched with spontaneous PVCs morphology. CA was performed at the location showing the best pace-match, typically over 95%. Furthermore, as PVCs causes a position shift in 3D mapping systems due to motion of the heart within the 3D coordinate system, we used the LAT-hybrid mode.

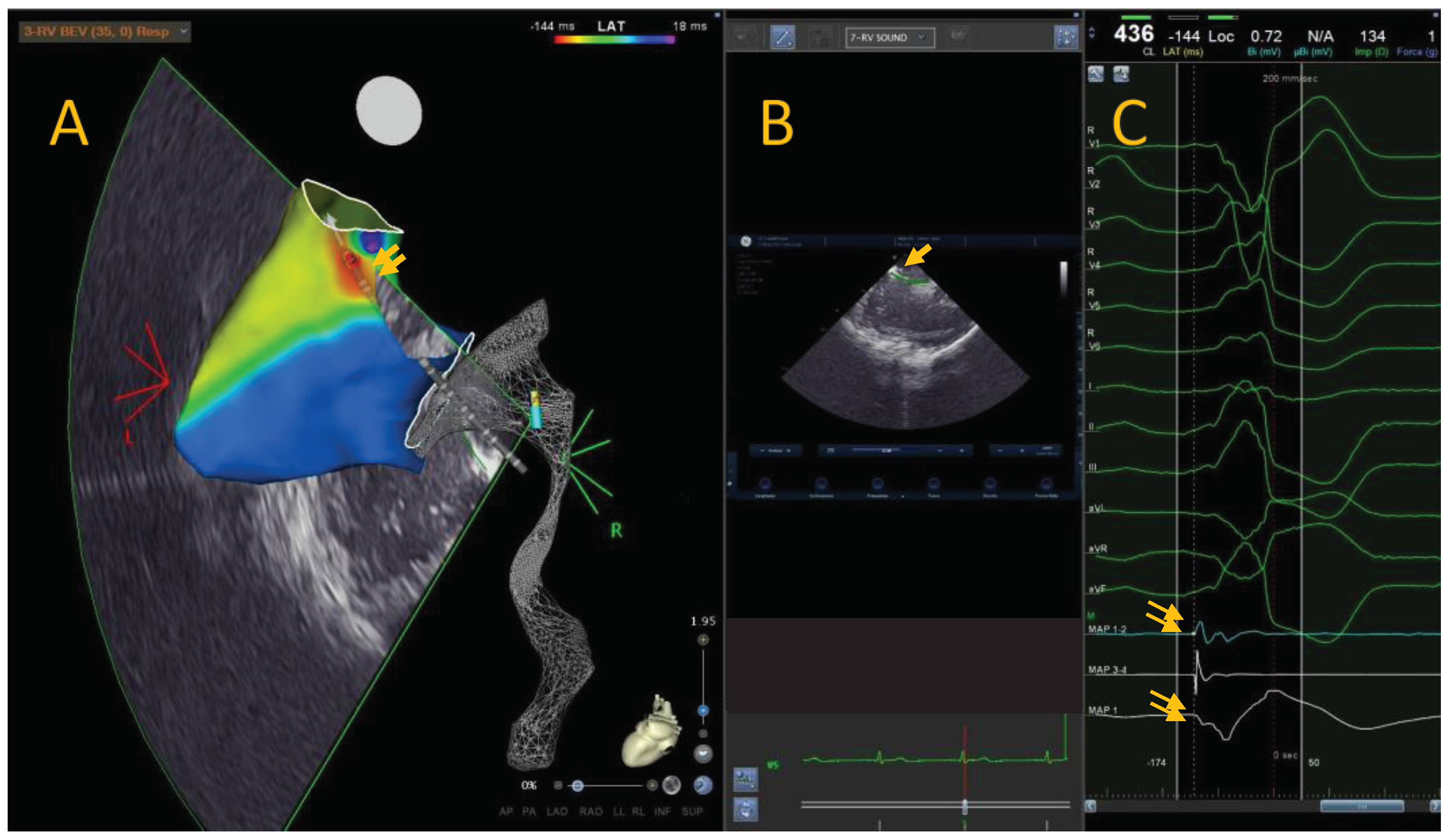

Anatomical mapping data were collected using a 3D mapping system (CARTO 3, Biosense Webster) and a conctact force mapping-ablation catheter (ThermoCool SmartTouch, Biosense Webster Inc., MA, US). The activation mapping was performed in each case: the PVCs origin site was defined as the earliest site of local ventricular activation preceding the onset of the QRS wave by at least 30ms on the surface ECG and with a QS signal in unipolar mapping (Figure A).

Figure A.

Local activation time map of a 36-years-old leisure time sportsman with idiopathic PVCs from RVOT. The colorimetric map shows that the main site of onset of PVCs is the posterior RVOT. In this region, we can see the ablator catheter in transparency, with the tip at the level of the region of interest (A). Through intracardiac echocardiography and specific module (CARTOSOUND® Module with SOUNDSTAR®) it is possible to integrate the electro-anatomical map with intracardiac echocardiographic map. It is possible to view the position of the catheter and tip with the ICE (B). The bipolar ablator catheter signal shows a clear advance compared to the surface QRS signal, and the unipolar signal is represented by a QS signal (C).

Figure A.

Local activation time map of a 36-years-old leisure time sportsman with idiopathic PVCs from RVOT. The colorimetric map shows that the main site of onset of PVCs is the posterior RVOT. In this region, we can see the ablator catheter in transparency, with the tip at the level of the region of interest (A). Through intracardiac echocardiography and specific module (CARTOSOUND® Module with SOUNDSTAR®) it is possible to integrate the electro-anatomical map with intracardiac echocardiographic map. It is possible to view the position of the catheter and tip with the ICE (B). The bipolar ablator catheter signal shows a clear advance compared to the surface QRS signal, and the unipolar signal is represented by a QS signal (C).

Radiofrequency energy pulses were delivered with a 3.5mm tip irrigated ablation catheter (ThermoCool SmartTouch™, Biosense Webster Inc., MA, US) at a power of 35 to 50W with a target Ablation Index of 550 to 630 [

23,

24]. If the PVCs were abolished, an additional pulse of radiofrequency was delivered at the same site. If PVCs were still present, mapping was continued to find an optimal target site. A future perspective is represented by new technologies, such as new catheters and new forms of energy [

25].

Follow-up

For both athlete and non-athlete patients it was forbidden to practice sports for at least two weeks, after the procedure.

All patients performed a 24 hours Holter ECG monitoring 3 to 6 months after the index procedure. Patients were evaluated with an in-office visit after 9 to 15 months, with physical examination and 12-lead ECG. Patients for whom an in-office check-up could not be scheduled were examined by telephonic monitoring.

When patients reported symptoms of palpitations, dizziness, or syncope during follow-up, they were advised to contact their referring physician immediately for adequate evaluation with 12-lead ECG and, possibly, with a 12-lead 24-hour Holter monitoring.

Study end-Point

The primary procedural outcome of the study was PVCs post-ablation reduction in athletes and non-athletes group, evaluated with 12-lead 24 hour ECG Holter monitoring, performed 3-6-months after ablation.

The secondary procedural outcome of the study was PVCs post-ablation reduction in agonist and leisure-time athletes.

The third procedural outcome was the evaluation of the resumption of physical activity and of the subjective improvement of symptoms in both agonist and leisure-time athletes.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were checked for normality with the Shapiro-Wilk test and presented as mean and standard deviation (SD) if normally distributed, or as median and interquartile range (IQR: 25th percentile, 75th percentile) if non-normally distributed. Categorical variables are given as count and percentage (%). Comparison between groups were made with chi squared test, student t test and Mann-Whitney U test. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. The software Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS ® Inc. IBM ®, NY) was used for statistical analyses.

Results

Patient Population

The baseline characteristics of all patients have been summarized in

Table 1.

The patients enrolled in the study were selected based on the presumed origin of ventricular extrasystole, determined through the analysis of the 12-lead electrocardiogram. Initially, 84 patients with RVOT/LVOT/fascicular presumed origin were included in the study. Then, 5 patients were excluded as electroanatomic mapping did not confirm the origin of extrasystole in these locations (4 LV summit, 1 mitro-aortic continuity).

Of the 79 enrolled patients (mean age 46 ± 14,5 years; male 51, 65%), the majority had no cardiovascular risk factors, and both the dimension and the function of the right and left ventricles were within normal limits. More than half of the enrolled patients were already on beta-blocker therapy, while a smaller proportion were receiving treatment with flecainide or amiodarone. The median number of PVCs in the enrolled patients was very high (median 19600, IQR 11100 – 30600]. All 79 presumed origin from 12 lead ECG were confirmed with electro-anatomical mapping (57 (72%) from RVOT, 19 (24%) from LVOT and 3 (4%) fascicular).

Out of the 79 patients enrolled, 23 (30%) did not undergo MRI, while 56 (70%) underwent the examination to more precisely exclude potential structural heart conditions.

Among the 56 MRI conducted, 37 yielded negative results for both structural heart issues (including wall thickness, ventricular chamber volumes, and wall motion abnormalities) and the detection of LGE areas.

The remaining 19 MRI scans, however, revealed the presence of areas with LGE but consistently showed no signs of structural heart problems. In all cases, MRIs demonstrated limited areas of LGE (<20%) in the left ventricle, in regions unrelated to the presumed PVCs origin. Specifically, LGE areas were exclusively in the pericardium in 5 patients (suggestive of previous pericarditis), in the anterior/junctional septal area in 3 patients, within the intramyocardial region along the basal posterolateral wall and within the anterolateral wall respectively in 8 and 3 patients (suggestive of myocardial inflammation).

Comparison of Athlete and Non-Athlete Groups

The non-athlete group consisted of 37 patients (mean age 53,2 ± 11,2 years; male 24, 64%), while the athlete group included 42 patients (mean age 39 ± 12,8 years; male 27, 64%).

The non-athlete group had a statistically higher mean age than the athlete group. In addition, the incidence of cardiovascular risk factors was slightly higher in the non-athlete group. No significant differences were observed in the use of antiarrhythmic medications between the two groups, with the exception of beta-blockers, which were statistically less commonly used in athletes (p<0.001). Finally, there were no statistically significant differences in echocardiographic characteristics between the two groups, nor in PVC burden at baseline 24-hour ambulatory ECG monitoring.

In athletes group, the leisure-time subgroup consisted of 23 patients (42 ± 12,5 years; male 13, 57%), and the agonist subgroup included 19 patients (32,9 ± 12,9 years; male 14, 74%). Agonist athletes were significantly younger than leisure-time athletes. No statistically significant difference was found between the two subgroups with respect to echocardiographic features and antiarrhythmic drugs therapy.

As expected, agonist athletes had a statistically significant greater number of weekly workouts and weekly training hours compared to the leisure-time athletes (3 [IQR 2-3] vs. 4 [IQR 3-5] workouts per week and 5 [IQR 3-6] vs. 9 [IQR 7-12] hours per week). However, no significant differences in PVCs-induced symptoms were observed between the two subgroups.

The baseline characteristics of athlete subgroups have been summarized in

Table 2.

Procedural Data

All procedural data are presented in the table, with no statistically significant differences between the groups, with rare exceptions.

Activation mapping was conducted on all patients, both athletes and non-athletes. In some instances, a combination of drug infusions, such as caffeine and isoproterenol (20-30% of cases), and stimulation protocols (approximately 10% of cases) were employed to facilitate PVCs induction. Pace-Mapping maneuvers were employed in the vast majority of cases, consistently yielding excellent matching values (>95%). Mapping procedures were consistently performed using the ablator catheter, except in rare cases where multipolar catheters were necessary. The median maximum advancement of the ablator catheter signal on the surface QRS was 30ms.

Once the region of interest was precisely identified, a limited number of deliveries and a constrained total delivery time were required (median of 6 VisiTags per procedure and 2.2 cm2 of ablated area, with a total delivery duration of approximately 175 ms). The maximum achieved AI was consistently >600. Fluoroscopy times were notably shorter in athlete patients compared to non-athletes, especially in agonist patients (

Table 3).

The median 24 hours PVCs in non-athletes patients was 17.000 (IQR 10000-30000), and 18750 (IQR 10000-30700) in athletes. The most frequent PVCs origin site was the RVOT (59 out of 79 patients, 72%), even more frequently in athletes against non-athletes (80% vs. 62%); in both groups the most affected region of the RVOT was the anterior region (40% group 1, 38% group 2), followed by the septal and posterior regions (26% vs. 32% and 34 vs. 30%, respectively).

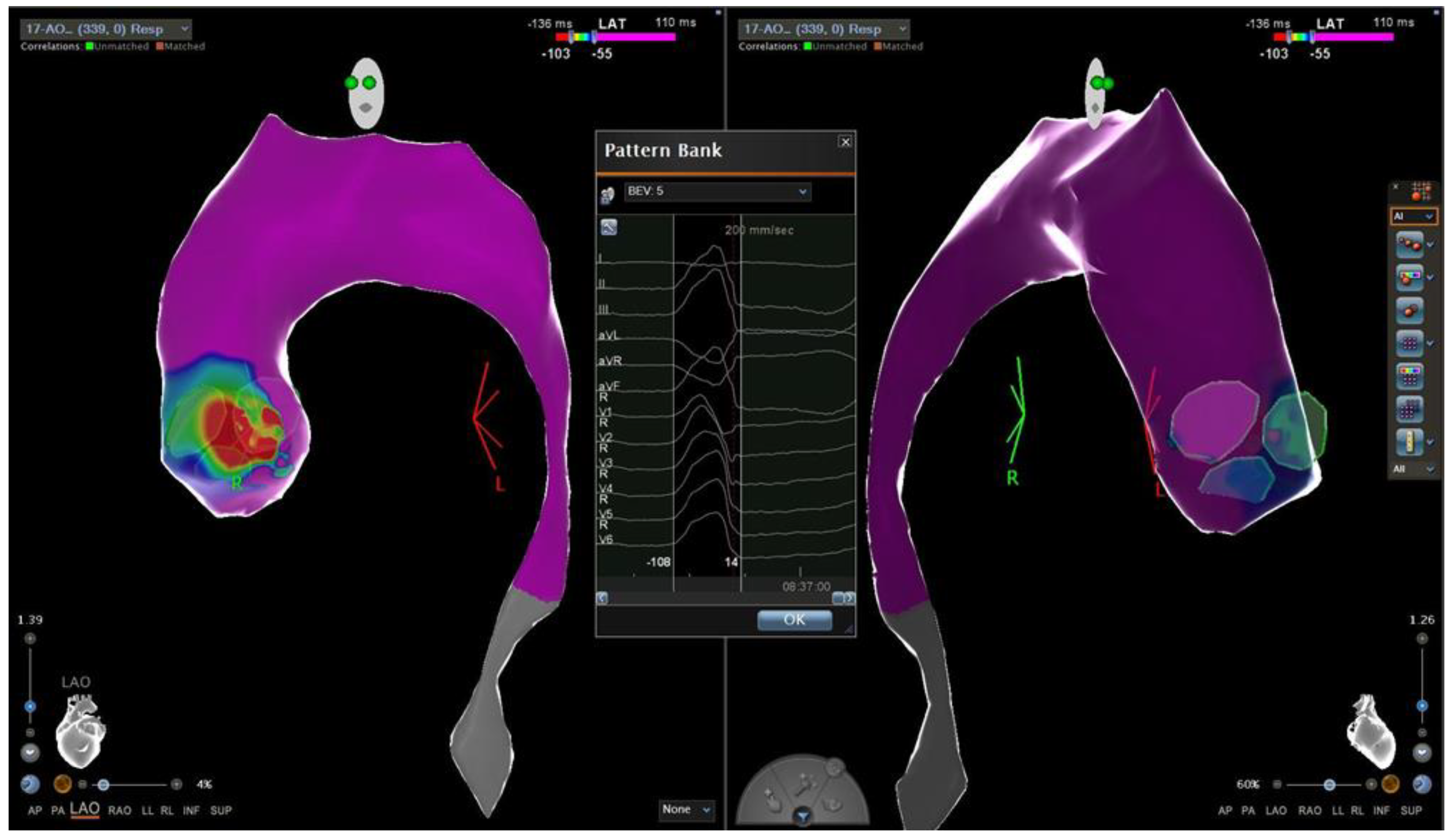

Conversely, LVOT PVCs ablation was more frequently performed in non-athletes patients compared to athletes (32% vs. 17%) (Figure B).

Figure B.

Local activation time map of a 24-years-old sedentary man with idiopathic PVCs from LVOT. The colorimetric map shows that the main site of onset of PVC is the region of the commissure between the left and the non-coronary aortic cusp.

Figure B.

Local activation time map of a 24-years-old sedentary man with idiopathic PVCs from LVOT. The colorimetric map shows that the main site of onset of PVC is the region of the commissure between the left and the non-coronary aortic cusp.

Acute efficacy, defined as absence of the PVCs observed during the first 30 minutes of ECG-monitoring after CA and/or at ECG-telemetry monitoring during the first 24 hours after CA, was achieved in 86% of non-athletes and 90% of athletes.

No major complication occurred; only 4 vascular minor complications (all pseudo-aneurysm) occurred and none required surgery (

Table 4 and 5).

Before CA, the median 24 hours PVCs in leisure-time patients was 26.500 (IQR 11000-26700), and 12000 (IQR 10000-27000) in agonist. The most frequent PVCs origin was the RVOT, followed by LVOT and fascicular origin. The statistical analysis revealed no statistically significant differences in the site of origin between the leisure-time and agonist groups.

Outcomes

All patients, 3-6 month after the procedure, underwent 12-lead Holter ECG monitoring. The median 24 hours PVCs in non-athletes patients was 1000 (IQR 341 – 4916) and 300 (IQR 167 – 851). For each patient, the percentage of decrease in PVCs number between the pre-procedure and post-procedure 12-lead Holter monitoring was evaluated: the median percentage of decrease in non-athletes group was 96% (IQR 68 – 98) and 98% (IQR 92 – 99) in athletes group. No statistically difference were found in the PVCs percentage reduction after the ablation procedure between non-athletes and athletes group (p=0,08). Considering only the athletes, the median PVCs burden at 12-lead Holter ECG monitoring was 300 (IQR 230-800) and 260 (IQR 160-100) respectively in leisure-time and agonistic patients. The median percentage of decrease in PVCs number between the pre-procedure and post-procedure 12-lead Holter monitoring was 98% (IQR 93-99) and 98% (IQR 87-99) respectively in leisure-time and agonistic patients. No statistically difference were found in the PVCs percentage reduction after the ablation procedure between leisure-time and agonistic group (p=0,42) (

Table 6).

Post-Ablation Sport Activity

The pre-ablation values were compared with the corresponding post-ablation values to assess and evaluate the resumption of physical activity after the procedure.

Sixteen (70%) leisure-time and 17 (90%) agonist athletes (p=0,24) have resumed physical activity 3 months after PVCs CA; among agonistic athletes, 59% have resumed competitive physical activity.

There are no statistically significant differences in the number of pre- and post-procedural training sessions and weekly training hours between athletes who have resumed physical activity, regardless of whether they were agonist or leisure-time athletes.

No statistically significant differences were observed among agonist and leisure-time athletes, in terms of the number of workouts (p=0,97 and p=0,15) and weekly training hours (p=0,92 and p=0,10) before and after the procedure.

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the effects of CA of idiopathic PVCs in non-athletes and athletes, both agonist and leisure-time athletes. Furthermore, we evaluated the post-ablation resumption of physical activity and the subjective improvement of symptoms in agonist and leisure-time athletes.In our experience, CA has confirmed a high efficacy rate in treating idiopathic PVCs, not only among non-athletes but also in athletes. Athletes who undergo CA exhibited a notable rate of resumption of physical activity; after ablation, athletes experienced a significant improvement in exercise tolerance, reflecting the positive impact of such an effective procedure on their overall fitness level.

As the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines state, CA is a recommended therapeutic strategy to treat symptomatic patients with presumed idiopathic PVCs, especially for those originating from RVOT and left fascicles. In literature, a high success rate of CA of idiopathic PVCs has been reported, with rare complications, particularly for the RVOT and fascicular ones [

6]. In our series, we fully analysed patients who underwent CA for apparently idiopathic PVCs. Subsequently, we categorized the patients into two groups: non-athletes and athletes. Within the athletes group, we further classified them into agonist and leisure-time for further investigation.

As expected, the median age of non-athletes was significantly higher than that of athletes, and similarly, the median age of leisure-time was greater than that of agonists. However, there are no other discernible differences in terms of clinical characteristics and echocardiographic features between these groups.

Use of antiarrhythmic drugs before CA was smaller in athletes than in non-athletes, without a statistically significant difference. Notably, beta-blocker therapy, the most commonly prescribed drug in the non-athlete group, was almost always avoided in the athlete group. There are several reasons for this discrepancy: firstly, introducing beta-blocker drugs into therapy for athletes is more challenging due to their typically higher vagotonic tone and lower rest heart rate; secondly, such therapy can potentially impact their physical sports performance, which is less desirable for athletes; furthermore, athletes often decide for ablation at an earlier stage compared to non-athletes, and sometimes they do so without testing any medical therapy, in order to obtain consent for resuming sports, which is a priority for them.

Regarding the site of origin of PVCs, it was observed that those originating from RVOT were more common compared to those from LVOT and fascicular regions, regardless of whether patients were athletes or non-athletes. Although the difference was not statistically significant, PVCs from LVOT tended to occur more frequently in non-athletes. Interestingly, the non-athlete patients tended to be older and with an higher prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors; as suggested by Kurshunov and Co. [

26], these factors are associated with a higher occurrence of LVOT PVCs.

The number of PVCs detected during the 24-hours pre-procedural Holter ECG monitoring was found to be remarkably high in both athletes and non-athletes group, with a median count of 17.000 and 18.750, respectively. However, when comparing athletes, the agonists showed a slighty lower number of PVCs compared to leisure-time athletes, although this difference was not statistically significant. This finding can potentially be explained by the fact that agonist athletes undergo regular sports check-ups, enabling the early detection of PVCs and prompt consideration of ablative options. Furthermore, athletes requiring agonistic fitness certification undergo CA in earlier stages.

Regarding the acute efficacy of CA and the number of PVCs recorded in the 12-lead post-procedure Holter ECG, the results of CA for PVCs were consistently excellent in all patient groups. These data confirm that CA is an outstanding therapeutic option for treating idiopathic PVCs, even among athletes and individuals engaged in sports.

Due to symptoms at rest and/or during physical activity, many athletes affected from PVCs either suspended or significantly decreased their participation in physical activities, as they were unable to maintain their competitive fitness. This reduction in physical activity was observed in approximately 80% of leisure-time and 85% of agonist athletes either at the time of diagnosis or shortly before it.

Regarding the resumption of physical activity after ablation, a significant percentage of leisure-time (70%) and agonist (90%) athletes were able to resume physical activities, suggesting that the interventional ablative option does not discourage patients from engaging in physical activity but rather encourages their recovery. However, among patients who previously engaged in competitive sports and who resumed physical activities after CA, approximately 40% did not resume activities at the same competitive intensity level.

In particular, regarding the frequency and duration of weekly workouts, although there were no statistically significant differences, both the number of workouts and training hours showed a numerical decrease after the ablative procedure. It is important to underline that these findings may be influenced by the restrictions imposed by the SarsCov2 pandemic, and also by a gradual resumption of physical exercise, eventually reaching a plateau after a longer latency time.

Approximately 33% (n=14) of athletes (9 leisure-time athletes and 5 agonist patients) with a diagnosed high burden of PVCs had reported symptoms during physical exertion before CA. These symptoms included easy fatigue, dyspnea, and palpitations, which affected their physical activity.Among patients who resumed physical activity (n=33), a remarkable 88% (n=14) of leisure-time athletes and 70% (n= 12) of agonist athletes reported a significant improvement in functional capacity and post-ablation performance.

This data is surprising: there are far more individuals who experienced an improvement in physical performance during exercise compared to athletes who reported symptoms before CA.

This seemingly paradoxical result can be explained in two main ways:

_Patients with a high burden of PVCs who claimed to be asymptomatic may have developed compensatory mechanisms to deal with symptoms. They might have engaged in physical activity below their maximum potential, adapting to their chronic symptoms and thus delivering suboptimal performances.

_The ablative procedure, as an interventional approach, and the 24-hour post-procedure ECG Holter monitoring with documented decrease in PVCs could have had a placebo effect on patients, contributing to their perception of improved symptoms and performance.

Limitations

The main limitations of the study are:

_the patients' symptoms were collected without the presence of any questionnaire, but only through an interview with the doctor

_not all patients underwent cardiac MRI to more accurately exclude structural heart disease.

Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge this is the first study comparing the efficacy and safety of CA of benign PVCs in athletes vs non athletes. In our series, CA was effective and safe in both groups, reducing symptoms and allowing a quick and safe return to sports activities in athletes.

Special Thanks

Special thanks to the CARTO biomedical engineers of the Cardiology and Arrhythmology Clinic, University Hospital “Ospedali Riuniti” of Ancona, Giulia Santarelli and Michela Colonnelli for the work carried out in the collection and evaluation of engineering data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.V and M.C.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.V. and M.C.; writing—review and editing, all authors; visualization, all authors; supervision, M.C. and A.D.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

Dr. Dello Russo is a consultant for Abbot Medical; Dr. Casella has received speaker honoraria from Biosense Webster. All other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hingorani, P.; Karnad, D.R.; Rohekar, P.; et al. Arrhythmias seen in baseline 24-hour Holter ECG recordings in healthy normal volunteers during phase 1 clinical trials. J Clin Pharmacol 2016, 56, 885–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorzi, A.; Mastella, G.; Cipriani, A.; et al. Burden of ventricular arrhythmias at 12-lead 24-hour ambulatory ECG monitoring in middle-aged endurance athletes versus sedentary controls. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2018, 25, 2003–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graziano, F.; Mastella, G.; Merkely, B.; et al. Ventricular arrhythmias recorded on 12-lead ambulatory electrocardiogram monitoring in healthy volunteer athletes and controls: what is common and what is not. A. Europace 2023, 25, euad255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrado, D.; Drezner, J.A.; D’Ascenzi, F.; et al. How to evaluate premature ventricular beats in the athlete: critical review and proposal of a diagnostic algorithm. Br J Sports Med. 2020, 54, 1142–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mont, L.; Pelliccia, A.; Sharma, S.; et al. Pre-participation cardiovascular evaluation for athletic participants to prevent sudden death: position paper from the EHRA and the EACPR, branches of the ESC. endorsed by APHRS, Hrs, and SOLAECE. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2017, 24, 41–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeppenfeld, K.; Tfelt-Hansen, J.; De Riva, M.; et al. 2022 ESC Guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: Developed by the task force for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Endorsed by the Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC). European Heart Journal 2022, 43, 3997–4126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sana, M.; Al-Khatib, S.; Stevenson, W.J.; et al. 2017 AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for Management of Patients With Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation 2018, 138, e272–e391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.C.C.; Fisher, N.G.; McKenna, W.J.; et al. Detection of apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy by cardiovascular magnetic resonance in patients with non-diagnostic echocardiography. Heart 2004, 90, 645–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassone, B.; Muser, D.; Casella, M.; et al. Detection of concealed structural heart disease by imaging in patients with apparently idiopathic premature ventricular complexes: A review of current literature. Clin Cardiol. 2019, 42, 1162–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dello Russo, A.; Compagnucci, P.; Casella, M.; et al. Ventricular arrhythmias in athletes: Role of a comprehensive diagnostic workup. Heart Rhythm. 2022, 19, 9099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorzi, A.; D’Ascenzi, F.; Andreini, D.; et al. Interpretation and management of premature ventricular beats in athletes: An expert opinion document of the Italian Society of Sports Cardiology (SICSPORT). Int J Cardiol. 2023, 391, 131220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dello Russo A, Compagnucci P, Zorzi A et al. Electroanatomic mapping in athletes: Why and when. An expert opinion paper from the Italian Society of Sports Cardiology. 2023 Jul 15:383:166-174. [CrossRef]

- John, R.M.; Stevenson, W.G. Outflow tract premature ventricular contractions and ventricular tachycardia: the typical and the challenging. Card Electrophysiol Clin 2016, 8, 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdile, L.; Maron, B.J.; Pelliccia, A.; et al. Clinical significance of exercise-induced ventricular tachyarrhythmias in trained athletes without cardiovascular abnormalities. Heart Rhythm 2015, 12, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delise, P.; Sitta, N.; Lanari, E.; et al. Long-term effect of continuing sports activity in competitive athletes with frequent ventricular premature complexes and apparently normal heart. Am J Cardiol 2013, 112, 1396–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steriotis, A.K.; Nava, A.; Rigato, I.; et al. Noninvasive cardiac screening in young athletes with ventricular arrhythmias. Am J Cardiol 2013, 111, 557–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nucifora, G.; Muser, D.; Masci, P.G.; et al. Prevalence and prognostic value of concealed structural abnormalities in patients with apparently idiopathic ventricular arrhythmias of left versus right ventricular origin: a magnetic resonance imaging study. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2014, 7, 456–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, E.; HWang, C.E.; Kim, D.S.;et al. Premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) in young athletes. [CrossRef]

- Pelliccia, A.; Sharma, S.; Gati, S.; et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines on sports cardiology and exercise in patients with cardiovascular disease: The Task Force on sports cardiology and exercise in patients with cardiovascular disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). European Heart Journal 2021, Volume 42, 17–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latchamsetty, R.; Yokokawa, M.; Morady, F.; et al. Multicenter outcomes for catheter ablation of idiopathic premature ventricular complexes. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2015, 1, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Z.; Liu, Z.; Su, L.; et al. Radiofrequency ablation versus antiarrhythmic medication for treatment of ventricular premature beats from the right ventricular outflow tract: prospective randomized study. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2014, 7, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulletta, S.; Gasperetti, A.; Schiavone, M.; et al. Long-Term Follow-Up of Catheter Ablation for Premature Ventricular Complexes in the Modern Era: The Importance of Localization and Substrate. J Clin Med. 2022, 11, 6583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casella, M.; Gasperetti, A.; Gianni, C.; et al. Ablation Index as a predictor of long-term efficacy in premature ventricular complex ablation: A regional target value analysis. Heart Rhythm 2019, 16, 888–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasperetti, A.; Sicuso, R.; Dello Russo, A.; et al. Prospective use of ablation index for the ablation of right ventricle outflow tract premature ventricular contractions: a proof of concept study. Europace 2021, 23, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compagnucci, P.; Valeri, Y.; Conti, S.; et al. Technological advances in ventricular tachycardia catheter ablation: the relentless quest for novel solutions to old problems. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2023 Dec 13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10840-023-01705-7. Online ahead of print. [CrossRef]

- Korshunov, V.; Penela, D.; Linhart, M.;et al. Prediction of premature ventricular complex origin in left vs. right ventricular outflow tract: a novel anatomical imaging approach. [CrossRef]

- Anderson RD, Kumar S, Parameswaran, et al. Differentiating Right- and Left-Sided Outflow Tract Ventricular Arrhythmias: Classical ECG Signatures and Prediction Algorithms. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2019, 12, e007392. [CrossRef]

- Muser, D.; Tritto, M.; Mariani, M.V.; et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Idiopathic Premature Ventricular Contractions: A Stepwise Approach Based on the Site of Origin. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, E.; Fotuhi, P.; Yen Ho, S.; et al. Repetitive monomorphic ventricular tachycardia originating from the aortic sinus cusp: electrocardiographic characterization for guiding catheter ablation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002, 39, 500–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Table 1.

Baseline non-athletes and athletes characteristics. Value are counts, mean (SD) or median (first quartile, third quartile).

Table 1.

Baseline non-athletes and athletes characteristics. Value are counts, mean (SD) or median (first quartile, third quartile).

| |

GENERAL POPULATION (N=79) |

NON-ATHLETES (N=37) |

ATHLETES (N=42) |

P VALUE |

| AGE (YEARS) - MEAN (SD) |

46 (14,5) |

53,2 (11,2) |

39 (12,8) |

P < 0,0001 |

| MALE GENDER - N (%) |

51 (65) |

24 (64) |

27 (64) |

p= 0,9 |

| LVEF % – MEDIAN [IQR] |

56,5 (53 – 61) |

56 (50 – 60.5) |

55 (54 – 60) |

p= 0,37 |

| TAPSE (MM) - MEAN (SD) |

24,3 (3,1) |

24,2 (2,5) |

24,8 (3,6) |

p= 0,27 |

| RDV1 (MM) - MEAN (SD) |

36,2 (4,8) |

36 (5,3) |

36,7 (4,4) |

p= 0,2 |

| ILVEDV (ML/M2) - MEAN (SD) |

63,3 (13,8) |

63,5 (15,3) |

63,2 (11, 5) |

p= 0,46 |

| HYPERTENSION - N (%) |

12 (15) |

8 (21) |

4 (9) |

p= 0,23 |

| DYSLIPIDEMIA – N (%) |

18 (23) |

14 (37) |

4 (9) |

p= 0,006 |

| DIABETES MELLITUS – N (%) |

2 (3) |

2 (5) |

0 (0) |

P= 0,9 |

| EGFR < 45 ML/MIN/M2 – N (%) |

1 (1) |

1 (2) |

0 (0) |

P= 0,9 |

PRE-ABLATIONA AAD THERAPY – N (%)

-BETA-BLOCKER – N (%)

-FLECAINIDE – N (%)

-AMIODARONE – N (%)

|

42 (53)

31 (39)

12 (15)

6 (7) |

28 (76)

23 (62)

7 (19)

5 (13) |

14 (33)

8 (19)

5 (12)

1 (2) |

P<0,001

p< 0,001

p=0,58

p=0,15 |

| N° WORKOUTS PER WEEK – MEDIAN [IQR] |

|

|

3 (2,75-4) |

|

| WORKOUTS HOURS PER WEEK – MEDIAN [IQR] |

|

|

6 (4,75-9) |

|

| SYMPTOMS DURING ACTIVITY – N (%) |

|

|

14 (33) |

|

Table 2.

Baseline leisure-time and agonist athletes characteristics. Value are counts, mean (SD) or median (first quartile, third quartile).

Table 2.

Baseline leisure-time and agonist athletes characteristics. Value are counts, mean (SD) or median (first quartile, third quartile).

| |

LEISURE-TIME (N=23) |

AGONIST (N=19) |

P VALUE |

| AGE (YEARS) - MEAN (SD) |

44 (12,5) |

32,9 (12,9) |

p = 0,004 |

| MALE GENDER - N (%) |

13 (57%) |

14 (74%) |

p = 0,4 |

| LVEF % - MEAN (SD) |

56,7 (6,5) |

56,6 (5) |

p= 0,46 |

| TAPSE (MM) - MEAN (SD) |

25,2 (4,2) |

24,2 (2,7) |

p= 0,19 |

| RDV1 (MM) - MEAN (SD) |

36,4 (5) |

37,1 (3,3) |

p= 0,5 |

| ILVEDV (ML/M2) - MEAN (SD) |

61,9 (12,8) |

64,8 (9,3) |

p= 0,21 |

| HYPERTENSION - N (%) |

3 (13) |

1 (5) |

p= 0,74 |

| DYSLIPIDEMIA – N (%) |

2 (9) |

2 (11) |

p= 0,74 |

| DIABETES MELLITUS – N (%) |

0 |

0 |

|

| EGFR < 45 ML/MIN/M2 – N (%) |

0 |

0 |

|

PRE-ABLATIONA AAD THERAPY– N (%)

-BETA-BLOCKER – N (%)

-FLECAINIDE – N (%)

-AMIODARONE – N (%)

|

7 (30)

4 (17)

2 (9)

1 (4) |

7 (36)

4 (21)

3 (16)

0 |

P=0,66

p=0,92

p=0,81

p=0,9 |

| N° WORKOUTS PER WEEK – MEDIAN [IQR] |

3 (2-3) |

4 (3-5) |

p= 0,003 |

| WORKOUTS HOURS PER WEEK – MEDIAN [IQR] |

5 (3-6) |

9 (7-12) |

P< 0,001 |

| SYMPTOMS DURING ACTIVITY – N (%) |

9 (39) |

5 (26) |

p= 0,58 |

| DECREASE OR INTERRUPTION OF PHYSICAL ACTIVITY – N (%) |

18 (80%) |

16 (85%) |

P= 0,92 |

Table 3.

Procedural data. Value are counts, mean (SD) or median (first quartile, third quartile).

Table 3.

Procedural data. Value are counts, mean (SD) or median (first quartile, third quartile).

| |

NON-ATHLETES (N=37) |

ATHLETES (N=42) |

P VALUE |

LEISURE-TIME (N=23) |

AGONIST (N=19) |

P VALUE |

| ACTIVATION MAP – N (%) |

37 (100) |

42 (100) |

P ns |

23 (100) |

19 (100) |

P ns |

PATTERN MATCHING – N (%)

PASO VALUE – MEDIAN [IQR]

|

34 (91)

97 [97-98] |

38 (90)

97 [95-98] |

P = 0,82

P = 0,23 |

20 (86)

97 [95-97] |

18 (94)

97 [96 – 98] |

P= 0,74

P= 0,65 |

| MAXIMUM SIGNAL ADVANCE (MSEC) – MEDIAN [IQR] |

30 [29-35] |

30 [28-38] |

P = 0,85 |

30 [29-37] |

30 [28-38] |

P= 0,88 |

| STIMULATION PROTOCOL – N (%) |

4 10) |

3 (7) |

P = 0,67 |

1 (5) |

2 (10) |

P= 0,86 |

| CAFFEINE/ISOPROTENEROL – N (%) |

8 (21) |

11 (26) |

P = 0,83 |

4 (17) |

7 (36) |

P= 0,28 |

MULTIPOLAR CATHETER – N (%)

ABLATOR CATHETER – N (%)

|

4 (10)

37 (100) |

3 (7)

42 (100) |

P = 0,67

P ns |

1 (5)

23 (100) |

2 (10)

19 (100) |

P= 0,86

P ns |

| RF TIME (SEC) – MEDIAN [IQR] |

175 [143-24] |

173 [146-246] |

P= 0,59 |

195[155-310] |

167 [145-230] |

P= 0,25 |

| VISITAG – N (%) |

6 [5,5-7,5] |

6 [5-9] |

P = 0,48 |

6 [5-9] |

5 [5-6] |

P= 0,09 |

MAX AI – MEAN (SD)

MEAN AI – MEAN (SD)

|

621 (21)

534 (57) |

610 (24)

546 (41) |

P = 0,16

P= 0,23 |

610 (18)

560 (32) |

605 (30)

535 (42) |

P= 0,25

P= 0,02

|

| ABLATION AREA (CM2) – MEDIAN [IQR] |

2,15 [1.6 – 3] |

2,2 [1.8-2.8] |

P =0,77 |

2,1 [1,8-2,8] |

2,25 [1,7-2,8] |

P= 0,7 |

| PROCEDURE DURATION (MIN) – MEDIAN [IQR] |

85 [75-135] |

85 [75-140] |

P = 0,66 |

90 [76-125] |

75 [67-147] |

P= 0,24 |

| FLUOROSCOPY TIME (MIN) – MEDIAN [IQR] |

12.5 [8-22] |

8,2 [5-10,5] |

P= 0,02 |

8,5 [6-14] |

6 [4-8] |

P= 0,02 |

| SVP – N (%) |

25 (67) |

29 (69) |

P= 0,9 |

14 (60) |

15 (79) |

P= 0,35 |

Table 4.

Procedural data information. Value are counts, mean (SD) or median (first quartile, third quartile).

Table 4.

Procedural data information. Value are counts, mean (SD) or median (first quartile, third quartile).

| |

NON-ATHLETES (N=37) |

ATHLETES (N=42) |

P VALUE |

SITE OF ORIGIN

- RVOT– N (%)

_SEPTAL RVOT – N (%)

_FREE WALL RVOT – N (%)

- LVOT– N (%)

- FASCICULAR – N (%)

|

23 (62)

14 (60)

9 (40)

12 (32)

2 (5) |

34 (80)

23 (67)

11 (32)

7 (17)

1 (3) |

p = 0,10

P= 0,8

P= 0,8

p = 0,16

p = 0,91 |

| PRE-PROCEDURE N° PVC – MEDIAN [IQR] |

17000

(10000-30000) |

18750

(10000-30700) |

p = 0,12 |

| ACUTE EFFECTIVENESS – N (%) |

32 (86) |

38 (90) |

p = 0,83 |

| MAJOR COMPLICATIONS – N (%) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

|

| MINOR COMPLICATIONS – N (%) |

2 (5) |

2 (4) |

p = 0,7 |

| POST-PROCEDURE N° PVC – MEDIAN [IQR] |

1000

(341 – 4916) |

300

(167 – 851) |

p = 0,09 |

Table 5.

Procedural data information. Value are counts, mean (SD) or median (first quartile, third quartile).

Table 5.

Procedural data information. Value are counts, mean (SD) or median (first quartile, third quartile).

| |

LEISURE-TIME (N=23) |

AGONIST (N=19) |

P VALUE |

SITE OF ORIGIN

- RVOT– N (%)

_SEPTAL RVOT – N (%)

_FREE WALL RVOT – N (%)

- LVOT– N (%)

- FASCICULAR– N (%)

|

18 (78)

12 (67)

6 (33)

4 (17)

1 (4)

|

16 (84)

11 (68)

5 (32)

3 (16)

0

|

p = 0,92

P=0,81

P= 0,81

p =0,78

p = 0,9 |

| N° PRE-PROCEDURE PVC – MEDIAN [IQR] |

26500

(11000-26700) |

12000

(10000-27000) |

p = 0,06 |

| ACUTE EFFECTIVNESS – N (%) |

20 (87) |

18 (95) |

p= 0,74 |

| MINOR COMPLICATIONS – N (%) |

1 (4) |

1 (5) |

p=0,55 |

| N° POST-PROCEDURE PVC – MEDIAN [IQR] |

300 (230-800) |

260 (160-100) |

p= 0,29 |

Table 6.

Post-ablation sport activity. Value are counts, mean (SD) or median (first quartile, third quartile).

Table 6.

Post-ablation sport activity. Value are counts, mean (SD) or median (first quartile, third quartile).

| |

LEISURE-TIME (N=23) |

AGONIST (N=19) |

P VALUE |

| RESUMPTION OF PHYSICAL ACTIVITY – N (%) |

16 (70) |

17 (90) |

p= 0,24 |

| RESUMPTION OF COMPETITIVE PHYSICAL ACTIVITY – N (%) |

|

10 (59) |

|

| WORKOUTS PER WEEK – N (%) |

2,5 (2-4) |

3 (2-4) |

p= 0,3 |

| WORKOUTS HOURS PER WEEK – MEDIAN [IQR] |

4 (3.25-6) |

7 (6-8,5) |

p= 0,007 |

| IMPROVEMENT OF SYMPTOMS DURING SPORT ACTIVITY - N (%) |

14 (88%) |

12 (70%) |

p= 0,44 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).