1. Introduction

In the last two decades, the relationship between physical activity and sports well-being has attracted the attention of the scientific community. All types of physical activity have been identified as promoting positive psychological well-being, regardless of the environment in which they are performed [

1,

2,

3] and are associated with high levels of life satisfaction, quality of life and happiness and the development of structures and resources for the individual to enjoy a stable and balanced life [

4]

Over time, scientists, health and fitness professionals have argued that regular physical activity is the best way to defend against the development of many ailments, disorders, diseases and to the strengthening of the immune system [

5,

6].

Being active is one of the most important habits that people of all ages can develop to improve their health. As physical fitness educators, we have an important mission to shape the health of those around us. With advancing age, physical fitness decreases and physical health limitations increase while sports activities are less frequent [

7]

We can also associate the term fitness with physical fitness in relation to health. Some researchers consider that there is no more important objective exists in the sport and exercise sciences than the attainment of physical fitness [

8]. Physical fitness is a common predictor of obesity and individual fitness levels may be more important than body weight in terms of maintaining good health status and well-being [

9,

10,

11]. The notion of physical fitness has a complex structure of skills (eg. muscle strength, muscular endurance, cardiorespiratory endurance, flexibility and body composition) that refers to the ability to perform physical activity [

12,

13,

14].

Maybe, physical fitness depends on the person’s health, physical condition and is an important contributor to healthy aging that improves cognition [

15,

16].

Because the time we conducted our study was affected by the periods of lockdown and isolation caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, we consider it useful to bring some information on how sports and physical activities were affected in all population groups. This pandemic situation has hampered the daily activities of almost all individuals, and abrupt changes have influenced every individual, many people who were regularly following their fitness activities in gyms, or in the ground, or other places before the lockdown has been affected intensely [

17].

It can be said with certainty that both physical activity and exercise are essential moments in both maintaining and improving our mental health and the quality of our lives [

18]. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has increased the attention of more and more people on the positive effects of exercise on physical health [

19]. During this period of COVID-19, it is essential for family members to take on a supporting role in promoting physical activity and exercise in the forms available to them [

20].

Among the negative effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the population was the decrease in the amount of physical activity and fitness among students [

21], eating problems, sleep disorders, inconsistency in maintaining intensity in physical activity [

22,

23]. In this regard, it is important to better understand changes in sleep levels or fluctuations in maintaining a constant intensity in physical activity due to a set of concerns and fears associated with this pandemic [

24].

Our experimental group was made up of students, so we mention the following: students are an extremely vulnerable group to a lifestyle based on a modest dietary intake, engaging in insufficient physical activity and sedentary behavior. Bertrand et al. (2021) examined the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on students dietary intake on physical activity and sedentary behavior, and their findings provide evidence to support the fact that the COVID-19 pandemic significantly increased students' sedentary behavior, their level of physical activity and negatively affected the intake of nutrients and calories [

25].

As we know, the amount of physical activity in Romania is low. The good intentions laid out on paper in various programs and strategies of the governments that lead the country are not enough, the development of physical activities at the level of mass sports remains limited in Romania [

26]. Possible causes would be underfunding and lack of predictability and concrete projects and programs to support the practice of sports, especially sports for all. In 2009, one of the largest market research institutions in the country indicated that 60% of Romanians did not practice any sport [

27]. Romanian researchers believe that for student population engaged in physical activity, the general difference in the level of physical activity between men and women was about 64% in MET minutes per week, namely, 6583 min for men and 4103 for women in the university environment. [

28]. From this perspective, the situation in our country is much lower than that of our neighbors in Hungary, where there is a more developed culture of movement but also a real support from the authorities and where a recent study shows that more than 80% of the population practices moderate or high level physical activities, which is reflected in a better control of BMI and in a good physical condition in relation to health [

29].

At the university level, researchers can successfully state the beneficial effects of physical activity on cognitive performance and academic performance in young adults [

30].

In support of our motivation to conduct this study was that the reliability of the assessment of test batteries for fitness in relation to health has been proven, providing useful information about the characteristics of potential test items in an adult test battery, as well as the limitations of its practical use [

31]. Over time, a series of test batteries have been proposed and implemented to assess fitness in relation to the health of the world's population, such as FitnessGram, developed by the Cooper Institute or EuroFit applied in EU countries [

32,

33]. For example a person who practices recreational sports, the battery of tests plays the role of assessing the physical condition in relation to health. Alternatively, a typical test battery may include upper and lower body strength tests, power tests, speed and agility tests, cardiovascular endurance tests, body composition tests, and flexibility tests [

34].

Testing the physical fitness on recreational athletes, could provide benefits similar to those seen in the competitive athletic population [

34]. Fitness promoters always offer support in trying to attract as many people as possible to this area through their long-term benefits [

35]. By using specific tests and measurements, it will be possible to assess all health-related fitness components [

36]. Physical activitiy and exercise are behavior/ habits, whereas physical fitness is an outcome of behaviors [

12].

2. Materials and Methods

In 2017, in Berlin, a promising program based on tests for the physical condition of the population was presented. European Fitness Badge (EFB) is a program that was developed as an online tool to assess the health of the population who are at least 18 years old and residing in the European space [

37]. The EFB project – a way of health related physical activity, was rigorously designed, based on scientific evidence, by a group of specialists from Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Denmark, Germany, Slovenia and Spain, and is funded by the European Union Erasmus+ program since 2015 [

38], and is aimed at the adult population of Europe, regardless of an individual's level of physical activity [

37]. Two of the authors of this study V.P.A and V.L.A. are certified instructors for the application of EFB in Romania, after participating in 2019, at the follow-up meeting/ multiplier seminar of the project and instructor training course in Berlin.

2.1. The purpose of the study

This study aims to obtain a set of realistic and objective data using a new battery of tests (EFB - European Fitness Badge) that asses the general physical condition in relation to health, on a group of 180 students from western Romania, from various study programs, especially after a period in which physical activity has decreased significantly due to restrictions caused by the COVID 19 pandemic. After performing the test, the instructor and the subject receive personal feedback, which has the role of guiding and motivating the population to perform individualized types of physical activity according to the needs of each individual. Giving this European fitness badge can make people aware of their physical level and help sustain self-confidence - resulting in a desire for self-improvement and an emotional commitment to physical activity that involves health (according to HEPA recommendations).

2.2. Hypotheses

We assume that (1) there are significant differences in endurance, strength, coordination, flexibility and overall fitness depending on the test profile (basic or advanced), demografic factors (sex and age), and student’s major (sport, economics, psychology, etc.); (2) ABSI predict better the level of fitness than BMI (there is a strong association between ABSI and overall fitness); (3) the test profile acts as mediator between demografic factors (sex and age) and fitness abilities (endurance, strenght, coordination, flexibility and overall fitness).

2.3. Participants

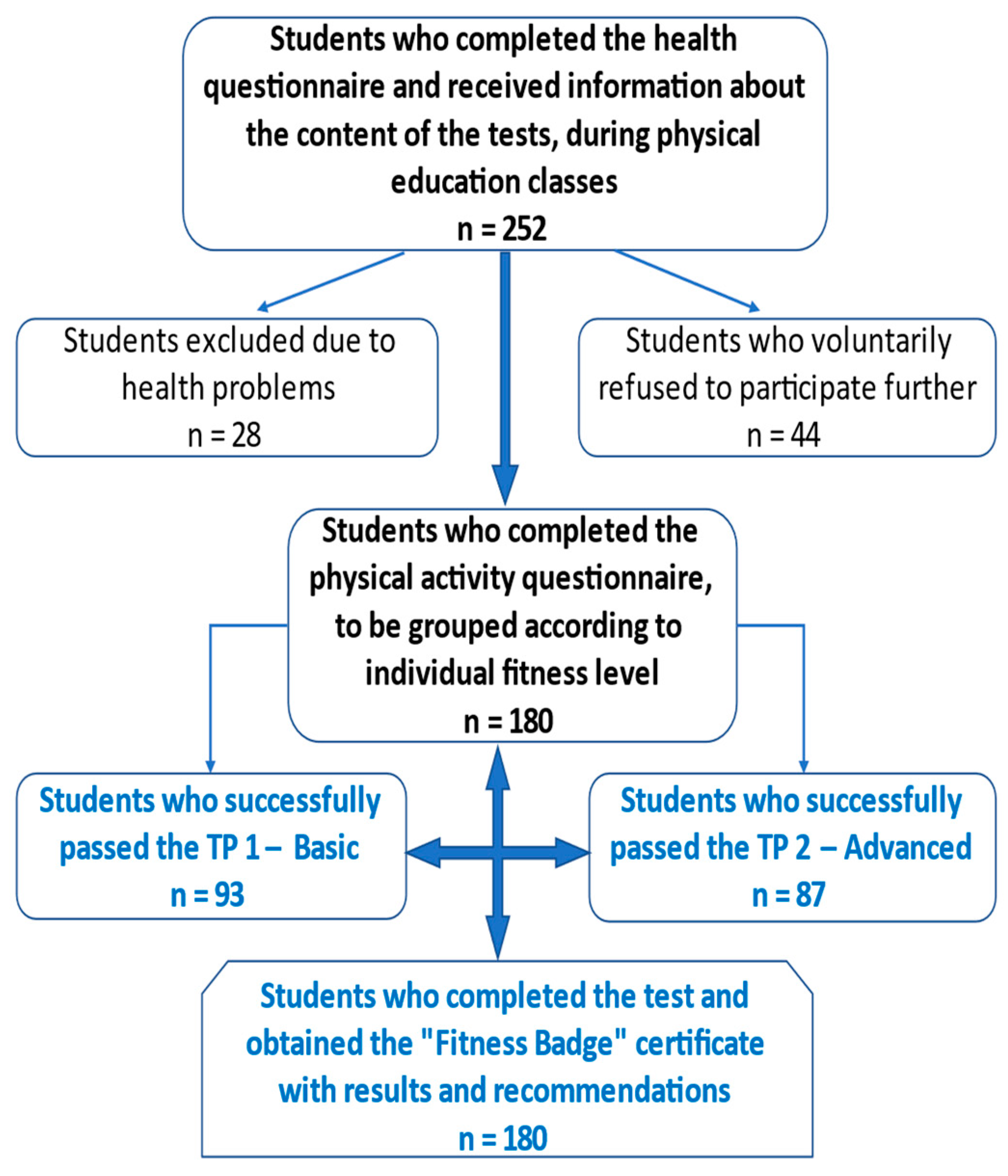

The investigation analyzed data from 180 Romanian college students, with 78 male (43.3%) and 102 female (56.7%) respondents, age ranged between min = 18 and max = 53 years, with the average age m = 23.59 and a standard deviation sd = 7.38 years. Participants were enrolled in various study profiles, as follows: sport (19.4%) N = 35, social work (20%) N = 36, psychology (8.9%) N = 16, engineering (18.3%) N = 33, computer sciences (14.4%) N = 26, accounting (10%) N = 18, pedagogy (8.9%) N = 16.

The basic tests (TP1) were performed by a number of 93 (51,7%) participants, 19 males (24.4%) and 74 females (72.5%), with a student’ major distribution of 29 (80.6%) social work students, 16 (100%) psychology students, 14 (42.4%) engineering students, 6 (23.1%) computer sciences students, 12 (66.7%) accounting students, and 16 (100%) pedagogy students. A number of 87 participants (48.3%) performed the advanced test profile (TP2), 59 males (24.4%) and 28 females (27.5%), with a student’ major distribution of 35 (100%) sport students, 7 (19.4%) social work students, 19 (57.6%) engineering students, 20 (76.9%) computer sciences students, and 6 (33.3%) accounting students.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study participants from different faculties.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study participants from different faculties.

2.4. Measurements and Tests

The EFB program is based on the health promotion principles of the HEPA program [

39] the target population is the adults (18 ≥ 65 years). By testing fitness factors, and the instructor implementing the EFB protocol, will be able to receive important information for exercise planning and adapt it to the needs of individuals [

40].

The European Fitness Badge (EFB) focuses on "health-related fitness." Several scientific studies indicate the most important components of fitness in relation to health as the following: - cardiorespiratory fitness (endurance), - muscular fitness (strength), - coordination and flexibility. In order to have a complete assessment, it is often advisable to measure other components such as - body composition (BMI) and - posture or possible gait deficiencies, these completing a better understanding of the level of fitness in relation to health [

12,

31,

39].

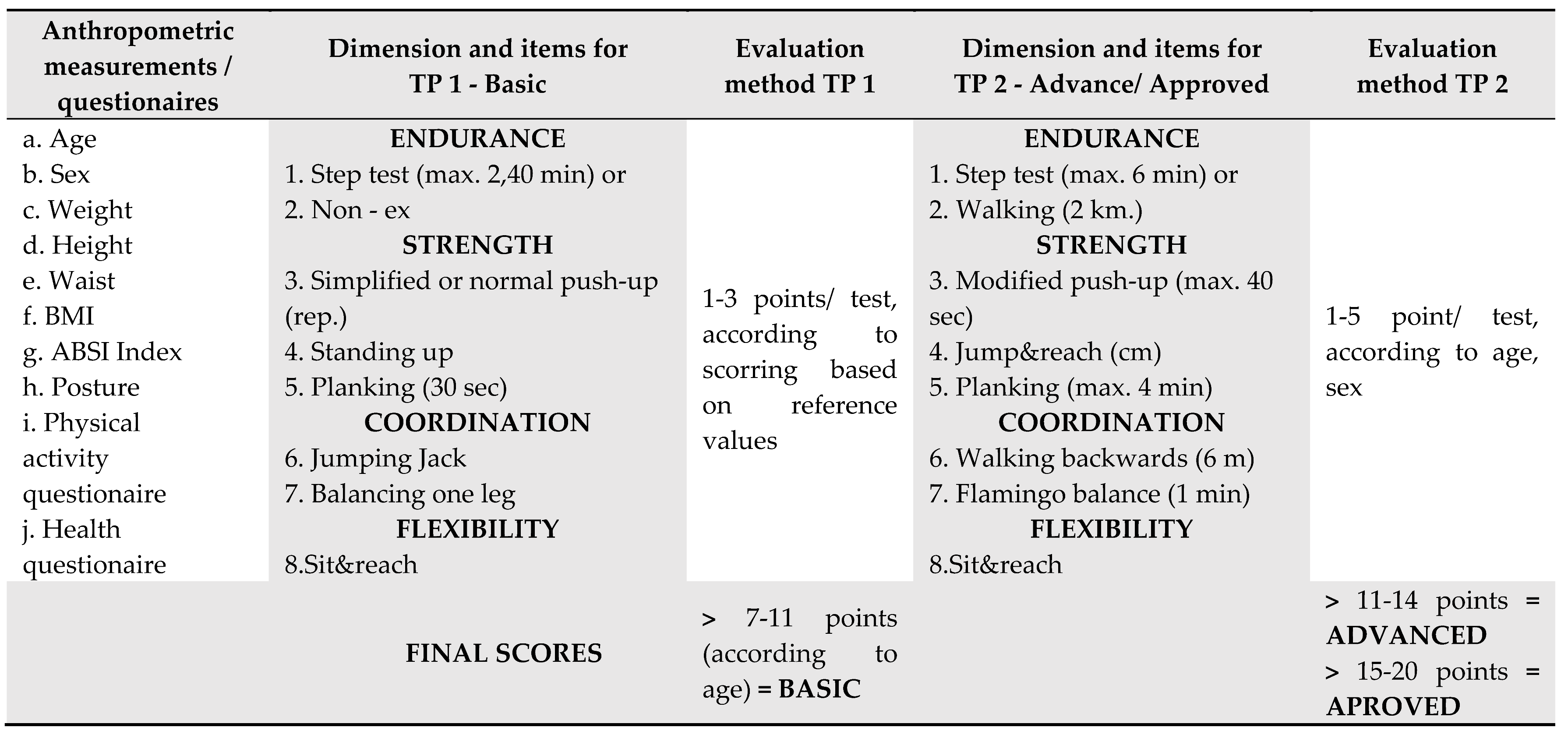

The EFB system is represented by the two profiles for testing some daily qualities or skills (TP1 and TP2). Test Profile 1 is focused on functional, simple skills and is especially for beginners and seniors in the context of health-promoting events. Test Profile 2 has a higher degree of difficulty, is performance-oriented and is aimed primarily at active men and women who play sports regularly, in or out of sports clubs or gyms. In addition to a certificate containing the results obtained and its classification, the participants receives a wide and individual feedback, including recommendations for improving or maintaining the activity he carries out.

Note that each person who participated in this test signed an informed consent statement. The subjects also completed a health questionnaire (PAR-Q - Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire), after which the test leader will decide if the participant were able to perform the test. Finally, the participants completed another questionnaire regarding the level of physical activities practiced in a normal week, with 5 items (eg item 1: “I just do my daily activities like house and family care” and so on), after which they were grouped into the two test profiles: Basic or Advanced according to the instructions in the EFB manual [

40].

There will also be other anthropometric recordings or measurements such as: age, sex, weight, height, waist circumference, BMI, ABSI index, posture assessment.

Test 1 (TP1 - Basic / Beginners) was designed to test basic physical condition. The test items are oriented toward simple functions of daily life (eg lifting from the chair with one leg). These will be assessed in three levels and scored as such.

If the subject's fitness level is not high enough to perform these basic functions, the subject needs to be integrated into special health-oriented exercise programs, with a strict focus on the person's requirements, such as overweight and and/ or other risk factors. The target group for this profile is sedentary adults and other physically inactive persons. With test 1, the tested subjects can obtain the EFB level 1 "Basic" certificate, if they accumulate the required score.

Due to the target group and the expected test settings, scoring and organizing are designed to be as easy as possible. Therefore, the score is equal for each person tested (the exception is the sit & reach test, where there is a distinction between men and women).

The score varies from 1 to 3 points depending on the performance obtained. The evaluation from 1 to 3 points was estimated by dividing the percentage. That is, between 60 and 80% of those tested should get the highest score of 3 points in each test. The TP 1 score was determined using the existing normative data in various studies.

As mentioned, in accordance with the score of each test, the tested person receives after evaluation from 1 to 3 points. The specific TP 1 samples are the following: - step test, - pushups, - sit and reach, - balance on one leg, - jumping jack, - plank, - lifting from the chair with one leg (see

Table 1). Subsequently, the results are summarized in dimensions/ components of fitness: endurance, strength, coordination and flexibility. If multiple test items/samples are performed for each dimension, the average value will be calculated, and if necessary, rounded up.

These performances will indicate the result for each of the four dimensions: endurance, strength, coordination and flexibility, where the person's strengths and weaknesses are highlighted. In the next stage, the results of all four dimensions will be summed up. This final value can range from 4 points (1 point in each dimension) to 12 points (3 points in each dimension).

The basic level is reached if the test person obtains the overall result, which is necessary for the appropriate age: - up to 40 years = min. 11 points; - between 41 - 50 years = min. 10 points, - between 51 - 60 years = min. 9 points, - between 61 - 70 years = min. 8 points, - over 70 years = min. 7 points.

For the endurance component, the instructor who coordinates the test has a choice between the following: - a performance test (Step test) or - a non-performance test (Non-Ex questionnaire), depending on the subject or materials available. Here, the step test should always be the first option.

For the strength component, two of the three tests must be performed. The three options are - plank test, which focuses mainly on the trunk stability; - lifting on one leg test, which focuses on the strength of the lower limbs, and - the pushup test, which focuses on the strength of the upper part, including the strength of the arms.

About the coordination component, the person must perform: - the balance test on one leg, and - the jumping jack test. The first highlights the static balance of the entire body, and the second tests the coordination of the body in motion.

The sixth test to be performed is - the sit & reach test for the flexibility component. This test element contains the flexibility of the lower back and the coxo-femoral area [

40].

Test 2 (TP2 - Advanced / Approved) is performance-oriented, for physically active adults who regularly practice sports, aiming to achieve the best results. The reference values are designed according to age and gender. The assessment is structured in 5 steps (quintiles), from "far below average" to "far above average." In turn, this test is subdivided into two groups: advanced - level 2 and approved/qualified - level 3, depending on the number of points obtained at the end. Due to the higher activity level and the expected settings, the score is more accurate. The score in test 2 corresponds to the age and sex of the person tested, which means that the result of each person tested will be compared with the results of the reference group in the general population.

The advanced fitness level corresponds to an average fitness level of the population (percentile range between 40-60) for the same age and sex, (ie the person tested has a better physical shape than 40% of the population, but less than 40% of the appropriate age and sex people). For those in this category are recommended more fitness activities with an emphasis on health status and can participate in the most exercise programs.

Qualified/approved fitness level means that the level is better than the average of the population (over 60th percentile) of the same age and sex, (so the person tested is among the most fit 40% of the corresponding age and sex group). Those in this group must continue healthy fitness activities, and can also perform challenging and competitive activities.

The person participating in the test will be evaluated initially for each samples to be taken. The specific TP2 samples are the following: - step test, - modified pushups, - sit & reach, - flamingo test, - reverse walk, - plank, - jump & reach (see

Table 1). Each result will be structured using age and gender specific rules, with a value in points from 1 to 5. The values of the points refer to quintiles: 1 point = 0-20th percentile rank, and 5 points = 81-100th percentile rank. Subsequently, the individual samples results are summarized by physical components/ dimensions (strength, endurance, coordination, flexibility).

If there are two or more samples on a component, then the average values will be calculated and, if necessary, rounded up. These performances will represent the test result on the four components: endurance, strength, coordination and flexibility. Strengths and weaknesses from a motric/ physical point of view can be seen here. In the next step, all four results obtained by components/ dimensions will be summed up in a single general result. This value ranges from a minimum of 4 points (1 point per dimension) to a maximum of 20 points (5 points per dimension).

Level 2 - Advanced will be achieved, if the person tested gets at least 11 points. This refers to a percentile rank of 40 or higher.

Level 3 - Approved / Qualified will be achieved if the person tested gets at least 15 points. This refers to a percentile rank of 60 or higher. People who get 19 or 20 points on the test will receive a special appreciation comment for their result.

The performance evaluation tables are structured according to age and gender, and the EFB award will take these criteria into account [

40].

2.5. Procedures and Research Design

For testing the first hypothesis, we made a quasi-experimental, unifactorial, cross-sectional design, having, in turn, as independent variables: test profile (basic or advanced), demografic factors (sex and age), age of the participants (4 age based groups) and student’s major (sport, economics, psychology, etc.) and a bifactorial design for combined effects of all independent variables. The dependent variables were endurance, strength, coordination, flexibility and overall fitness.

The second hypothesis has a corelational design, the tested variables being body mass index (BMI), a body shape index (ABSI) and overall fitnes of the participants.

The third hypothesis was investigated through a non-experimental mediation analysis design. In this research, sex and age of the participants were the independent variable, and fitness abilities (endurance, strenght, coordination, flexibility and overall fitness) were the dependent variable. The mediator variable was the test profile of the EFB - basic (TP1) and advanced profile (TP2).

2.6. Data Analyses and Results

For the statistical analysis, we used descriptive statistics (central tendency indices – mean, median, mode, and standard deviation), and Pearson correlation and one and two factor ANOVA were calculated on the basis of the collected data by using IBM SPSS version 24. The value of the significant threshold was set at maxim 0.05. To test the mediation relations, we use the add-on PROCESS version 3.5., [

41] to calculate the successive regressions to determine the mediation effect.

3. Results

To test the hypotheses, we performed the descriptive statistical analysis for the variables under study on the whole sample as well as separately for the groups formed according to the test profile: TP 1, N = 93 subjects, TP 2, N = 87 subjects (

Table 2). Following the descriptive analysis, there were evidenced tendencies toward differences between the two groups of subjects. Thus, given that a high score reflects a high level of physical abilities, in all cases the advanced profile participant scores were higher than those of the basic profile participants. The results reflect as well a lower BMI and ABSI indexes for the advanced profile participants.

Distributions of data were relatively symmetric for applying parametric inferential tests, therefore we tested the statistical significance with independent sample t-test for sex and test profile, and with one-way ANOVA for age and students’ major (

Table 3).

We observed significant differences between male and female participants for strength, t = 6.75, sig. = .00, (male: N = 72, m = 8.88; female: N = 102, m = 8.05) and coordination, t = 3.90, sig. = .00, (male: N = 72, m = 5.61; female: N = 102, m = 5.22), as well as between the test profiles for overall fitness, t = - 4.58, sig. = .00, (basic: N = 93, m = 10.86; advanced: N = 87, m = 12.66), endurance, t = - 4.26, sig. = .00, (basic: N = 93, m = 2.80; advanced: N = 87, m = 3.00), strength, t = -10.61, sig. = .00, (basic: N = 93, m = 7.87; advanced: N = 87, m = 9.00) and coordination, t = - 5.26, sig. = .00, (basic: N = 93, m = 5.15; advanced: N = 87, m = 5.65).

There are also differences in the strength variabile regarding the age of participants, F = 3.26, sig. = .023. The participants were divided into four age groups as follows: 19 - 25 years old, N = 140; 26 – 35 years old, N = 25; 36 – 45 years old, N = 11, and over 45 years old, N = 4). LSD post hoc test shows that this difference is significant between the youngest and the oldest group (sig. = 0.26). Because the age groups are extremely uneven and the results can be strongly biased, we applied the Pearson correlation for the age and strength, obtaining a coefficient r = - 0.27, sig. = 0.05, which concludes that the strength variabile decreases with age.

Moreover, the coefficients demonstrated significant differences regarding the students’ major. There are 7 groups of students’ majors as follows: sport, N = 35, social work, N = 36, psychology, N = 16, engineering, N = 33, computer sciences, N = 26, accounting, N = 18, pedagogy, N = 16. As shown in

Table 2, the differences are significant for overall fitness, F = 2.33, sig. = 0.034, endurance, F = 2.72, sig. = 0.015, strength, F = 7.64, sig. = 0.00, and coordination, F = 2.70, sig. = 0.016. Post hoc LSD tests show that the differences are between the sports students group and the others, mean scores for the sport group being higher than others.

To analyse the combined effect of sex, age, test profile and students’ major, we applied two-way ANOVA. After calculating the F test (

Table 4) we obtained a coefficient F = 4.174, sig. = 0.043 for overall fitness, and F = 8.575, sig. = 0.004 for strength, demonstrating that there are differences in overall fitness and strength due to the combined effect of sex and test profile.

The second hypothesis has a correlational design, the tested variables being body mass index (BMI), a body shape index (ABSI) and overall fitness of the participants. The Pearson correlation indices calculated (

Table 5) show a significant negative correlation between BMI and overall fitness, r = - 0.175, sig. = 0.019, and between ABSI and overall fitness, r = - 0.264, sig. = 0.00, which demonstrates that ABSI is a stronger predictor for fitness level than BMI.

In the mediation analysis, sex and then age of the participants are the independent variables and fitness abilities (endurance, strenght, coordination, flexibility and overall fitness) are the dependent variable. The mediator variable is the test profile of the EFB, basic (TP1) and advanced profile (TP2).

A series of steps were followed to quantify the mediation effect [

38]: verifying if all the studied variables (sex, age, test profile, fitness abilities) are statistically associated at significance lower than 0.05 (

Table 6); path c is calculated by regressing the dependent variabiles (fitness abilities) on the independent variabiles (sex and age) to ensure that the independent variabile is a strong predictor (

Table 7); by regressing the mediator variabile (test profile) on the independent variabile (sex and age) to verify that the independent variabile is a significant mediator variabile predictor; examining the pathways b and c' by regressing the dependent variabile (fitness abilities) on both the mediator variabile (test profile) and the independent variabile (sex and age) to validate that mediator variabile is an effective predictor of depending variabile (path b) (

Table 8). To validate the full mediation assumption, path b should be statistically significant, while path c should be non-significant. To access the statistical significance of the indirect effect is used PROCESS version 3.5., [

41].

Correlation coefficients (

Table 6) demonstrated associations between age and overall fitness (r = - 0.160, sig. = 0.03), and between age and strenght (r = - 0.207, sig. = 0.005); there are also correlations between sex and strenght (r = - 0.452, sig. = 0.00) and between sex and coordination (r = - 0.281, sig. = 0.00); test profile is correlated with all variabiles except flexibility, with Pearson coefficients ranging from 0.30 – 0.63 and sig. < 0.05.

Following the regression analysis (

Table 7), we get F coefficients at significant thresholds for preliminary testing with ANOVA when the predictor is sex variabile for strength (F = 45,61, sig. = 0.00) and coordination (F = 15.28, sig. = 0.00), when the predictor is age, for overall fitness (F = 4.66, sig. = 0.032) and strength (F = 7.96, sig. = 0.005) and when predictors are both sex and age, the regression is significant for strength (F = 26.25, sig. = 0.00) and coordination (F = 7.59, sig. = 0.001), which demonstrates a predictability relationship between these variables. Determination coefficients r2 and the standardized coefficient β demonstrate that sex determines 20.4% of the strength and 7.9% of coordination, as well as age determines 2.6% of overall fitness and 4,3% of strength. Regarding the both effect of sex and age, they determine 22,9% of strength and 7,9% of coordination.

The mediation effect of test profile was demonstrated by successive regression (

Table 8) in the relation between sex and overall fitness (F = 6.30, sig. = 0.001), strength (F = 49.41, sig. = 0.00) and flexibility (F = 2.71, sig. = 0.043), as well as in the relationship between age and overall fitness (F = 14.92, sig. = 0.00), strength (F = 44.04, sig. = 0.028) and coordination (F = 11.13, sig. = 0.023).

4. Discussion

Following the descriptive analysis, there were evidenced tendencies toward differences between the two groups of subjects based of the test profiles. Thus, given that a high score reflects a high level of physical abilities, in all cases the advanced profile participant scores were higher than those of the basic profile participants. The results reflect as well a lower BMI and ABSI indexes for the advanced profile participants. Therefore the results reflect the individual's habit of playing sports, participants with a long sports background accumulate a high score, also drawing the connection with their health and a healthy lifestyle, through low levels of BMI and ABSI indices. This shows that it is imperative and mandatory to include exercise programs in the daily routine of students . and, generally, of the population.

The sedentary lifestyle is growing alarmingly among the young population and is associated with many unhealthy consequences for the human being [

42]. In addition, the COVID-19 pandemic has changed the way people approach physical activity with some restraints and restrictions [

43,

44].

But in crisis situations, with many restrictions, the physical and mental conditions worsen and we could see how the pandemic situation has hampered the daily activities of almost all individuals, including those who depend on gyms to maintain good physical fitness in relation to their health [

17]. Through the tools provided by EFB we can easily identify the volume of physical activity of the people tested.

One can assume that active people compared to sedentary people should have better control on high-risk comorbidities that increase susceptibility to severe COVID-19 [

45,

46]. According to WHO [

47] physical activity and relaxation techniques can be valuable instruments for people to remain calm and continue to protect their health during pandemic period. Lockdown effects of COVID-19 affect people's level of physical activity and sedentary behavior [

48,

49].

In order for the health problems caused by coronavirus to be mitigated, induced by some restrictive measures taken by global authorities, sports professionals should encourage and provide solutions for organizations, local authorities and governments to promote alternative and safe mass-based physical activities [

50]. But we believe that it would be equally important to provide solutions for testing and evaluating the results and accumulations achieved, as a useful feedback to improve the training program and lifestyle. Thus, with the EFB test battery, we manage to satisfy these needs, especially with the help of the feedback certificate that contains the results and certain recommendations for the participants.

When we tested the statistical significance with independent sample t test for sex and test profile, we observed signifficant differences between male and female participants for strength, and coordination, with male participants having higher scores than female participants; as well as between the test profiles for overall fitness, endurance, strength, and coordination, with the advanced profile participants having higher scores than basic profile participants.

It is well-known fact that men generally have a higher level of strength than women, however, although the EBF scoring scales are lower for women than for men, men performed higher than women, reflecting the inclination of men to accumulate and develop muscle mass, implicitly strength, and also the preference of women for exercises to maintain the silhouette or mobility (e.g. aerobics and cardio clasees, Yoga, Pillates, etc). The volume of physical activity included them in the advanced profile of the test, but, due to the specifics of the female sports activity practiced, sports acquisitions differ, suffering certain limitations of multilateral motor development. Therefore, it is concluded that women need a broader approach to exercise. This information is provided by EFB, by applying this protocol it is offered the possibility of a fine control over the gaps in the quality of the sports activity practiced.

This is also highlighted by the differences between women and men in balance and coordination, considering the type of test in the EFB to assess this physical ability (e.g. flamingo test or walking back), which requires the lower body train, which benefits male subjects, who practice sports that mainly use the lower limbs (e.g. soccer), as in the case of the subjects in the research sample.

The differences observed in most physical abilities (strenght, endurance) emphasize the quality of EFB to correctly discriminate between people who exercise intensively, who have a large volume of training hours behind them, compared to sedentary people. Noting that each profile has different levels of assessment of the results [(e.g. the subjects who took the TP2 tests obtained the grades of Aproved (15.5 - 20 points), Advanced (10.5 - 15 points) and rejected (≤ 10 points)], there were subjects who did not meet the minimum score in both TP profiles, however, the averages achieved by the TP2 group of athletes were significantly higher than at TP1. Therefore, EFB tests are designed so that fitness skills are faithfully investigated, whether they are people with low exercise or people who have a daily workout routine.

For subjects who did not meet the passing test score, distributed approximately evenly on both samples (basic N = 20, advanced N = 21), an alarm signal was been raised by the fact that these persons (especialy from advanced group), who declared a reasonable volume of physical activities, unspecified in the score obtained, also included students who have chosen their specialization in sports and who, in theory, base their professional career on physical activity. As a result, they did not properly assess their physical fitness, but the EFB protocol provided detailed feedback on their weaknesses.

There were also differences when testing with one-way Anova for the strenght variabile regarding the age of participants, post-hoc test shows that this difference was significant between the youngest (19 – 25 years) and the oldest group (over 45 years). Because the age groups were extremely uneven and the results could be strongly biased, we applied the Pearson correlation for the age and strenght, which conclude that the strenght signifficantly decreases with age.

Therefore, once again, the EFB protocol demonstrates good fidelity of the results with reality, which meet expectations, is well known that getting older there are morpho-functional changes in the body, which limit physical activity. By constantly assessing fitness factors and individual feedback over the years, the EFB protocol helps the participant recognize individual improvement and continue an active lifestyle to improve or sustain fitness [

40]. In other words, the program stimulates and motivates the individuals to exercise and practice sports, both through direct assistance and structured tests, and by providing a certificate stating the results obtained, the fitness status at the time of the test and recommendations for improvements.

Furthermore, the coefficients demonstrated significant differences regarding the students’ major for overall fitness, endurance, strenght, and coordination, post-hoc tests indicated that the differences are between the sports students group and the others, mean scores for the sport group being higher than others.

Regarding the differences in averages obtained by students’ major, the results did not come as a surprise; as expected, students with sports specializations have significantly higher averages than other specializations, closely followed by engineering students in all assessed physical abilities. Students from the specializations of psychology, social assistance, etc. achieved similar results, with averages generally lower than those from sports and engineering. A possible explanation for the good results of the engineers may be the different specifics of the activity profile, the students with major in accounting or psychology, etc. being, by the profession, more sedentary than engineers. These results obtained by EFB tests suggest the need to involve students from sedentary profiles in physical activities, as they are more exposed to health risks due to physical inactivity.

The results indicated that there were differences in overall fitness and strenght due to combined effect of sex and test profile. Although expectations were that the groups of boys in both profiles obtained much higher averages than the girls, especially in terms of strength, a fact confirmed at TP1, (mm = 8.52, mw = 7.70), a probable explanation for the averages equal to TP2 (m = 9) can be the combined nature of the exercises, which is not a classic push-up, but consists of a combination of coordination and force movements, as described in the Measurement and Test (chapter 2.4.). Regarding the overall fitness, the results confirmed expectation (mm = 11.07, mw = 10.80) TP1, and at TP2 the girls were superior (mm = 11.84, mw = 14.37), a possible explanation would be the flexibility test that enters the score total, in which girls scored higher than boys. However, we consider that in some tests the score is not quite objective, we are mainly referring to the non-differentiation of the sex scales in the tests, and it would also be helpful to have more transparency in evaluating the results, to help their interpretation.

These results highlight the applicability of EFB for health diagnosis in relation to health, with the great advantage that the developers and promoters of the EFB protocol provide advice and training to those interested, seeking to expand the areas of knowledge of the evidence in this protocol [

37].

The results are consistent with other studies, Klemm et al. demonstrated that the EFB tool strongly differentiates between test profile, age, gender, and activity level, and the cumulative effect of gender and test profile is reflected in physical activity level, BMI, and postural problems [

37].

In the second hypothesis, the correlation indices showed a significant negative correlation between BMI and overall fitness, and a stronger one between ABSI and overall fitness, demonstrating that ABSI is a stronger predictor of fitness than BMI. In this regard, even EFB developers include the measurement of these 2 indexes as part of the instrument, to provide a complete picture of fitness and individual health. The data is also supported [

51] who considered the ABSI index an excellent predictor of disease and mortality, an anthropometric measure useful in conducting population health surveillance and assessing community needs.

Note that the ABSI index was derived from the waist circumference, which is independent of BMI and is believed to be a better interpretation index than the waist or BMI independently [

52]

. This index is a new anthropometric measure, implemented by Krakauer & Krakauer [

53] that simultaneously considered both waist and BMI. ABSI may be a much more reliable alternative than BMI in assessing cardiovascular risk factors in healthy individuals, or with a BMI in the normal range and centered obesity.

In the third hypothesis, the mediation analysis indicated the correlation and predictability between the variables. The correlations show that older students have a better level of overall fitness than their younger colleagues, moreover, endurance, strength and coordination show a downward trend in relation to age. Also, the girls' scores showed a downward trend in all motor qualities, significant especially in terms of tension and coordination, and the profile test showed clearly superior results of the students who took the tests from the advanced profile.

Regression analysis demonstrated that sex determines 20.4% of the strength and 7.9% of coordination, as well as age determines 2.6% of overall fitness and 4,3% of strength. Regarding the effects of both sex and age, they determine 22,9% of strength and 7,9% of coordination.

The mediation effect of the test profile of European Fitness Badge (EBF) in the relation between sex and overall fitness, sex and strength, sex and flexibility, as well as in relation between age and overall fitness, age and strength, age and coordination, demonstrate that the physical exercises in each test profile have a wide applicability so that the final result obtained reflects the particularities of the individuals, both in terms of sex characteristics and age.

This analysis revealed many possibilities for future research, such as replicating evidence on other types of samples: active population with different occupational categories, retirees, differentiation by living environment (urban and rural areas), specific geographical areas (mountain, plain), etc.

Moreover, the usefulness and applicability of EFB on broad age groups is highlighted, to identify the needs and dysfunctions of certain age stages, e.g., adults, seniors, etc.

Additionally, the applicability and validity of the EFB instrument, through studies conducted at the level of the international scientific community, can generate a body of empirical evidence available to coaches or sports and healthcare professionals.

5. Limitations and Strengths

Limitations

The study focuses exclusively on university students, which may limit its applicability to the general population. Different age groups or non-student populations might exhibit different fitness patterns.

As a cross-sectional study, it captures a snapshot in time and cannot establish causality or track changes over time.

The participants were university students, potentially leading to a selection bias if these individuals are more health-conscious or physically active than the general population.

If any part of the EFB system relies on self-reporting, there may be biases in the data due to underreporting or overreporting of physical activities.

The study is conducted within a specific cultural and academic environment (U.A.V. Arad), which may influence the fitness levels and behaviors of participants. These findings might not be fully transferable to other cultural or academic contexts.

Without longitudinal data, it's challenging to determine the long-term effectiveness of the EFB system in improving or maintaining fitness levels.

Strenghts

The use of the European Fitness Badge (EFB) system, which evaluates key components of physical condition (endurance, strength, coordination, flexibility) and anthropometric measurements, provides a thorough assessment of fitness levels.

The study involved 180 students from various study programs, offering a broad perspective on fitness levels across different demographics. The inclusion of both male and female participants of different ages enhances the generaliztion of the findings.

The research examines fitness levels in relation to several factors, including test profile (basic or advanced), demographic factors (sex, age), and students' majors. This multifaceted approach allows for a deeper understanding of the influences on physical fitness.

The study's use of ABSI (A Body Shape Index) in addition to BMI (Body Mass Index) provides a more nuanced view of the relationship between body composition and overall fitness.

The findings can inform strategies for fitness education and training, particularly in academic settings, and highlight the importance of physical exercises in maintaining health.

Overall, while the study provides valuable insights into the fitness levels of a specific group and the potential benefits of the EFB system, these limitations should be considered when interpreting the results and applying them to broader contexts.

6. Conclusions

In this study, there were evidenced tendencies toward differences between the groups of subjects based on the test profile. Thus, given that a high score reflects a high level of physical abilities, in all cases the advanced profile participant scores were higher than those of the basic profile participants. The results reflect as well a lower BMI and ABSI indexes for the advanced profile participants.

By testing with independent sample t-test for sex and test profile, we observed significant differences between male and female participants for strength, and coordination, with male participants having higher scores than female participants; as well as between the test profiles for overall fitness, endurance, strength, and coordination, with the advanced profile participants having higher scores than basic profile participants.

There were also differences when testing with one-way ANOVA for the strength variabile regarding the age of participants, a post hoc test showed that this difference was significant between the youngest (19 – 25 years) and the oldest group (over 45 years). Because the age groups were extremely uneven and the results could be strongly biased, we applied the Pearson correlation for the age and strength, which concludes that the strength significantly decreases with age.

Furthermore, the coefficients demonstrated significant differences regarding the students’ major for overall fitness, endurance, strength, and coordination, post hoc tests indicated that the differences were between the sports students group and the others, mean scores for the sport group were higher than those for the others. The results indicated that there were differences in overall fitness and strength because of the combined effect of sex and test profile.

The correlation indices showed a significant negative correlation between BMI and overall fitness, and a strong one between ABSI and overall fitness, demonstrating that ABSI is a stronger predictor of fitness than BMI.

The mediation analysis indicated the correlation and predictability between the variabiles. Regression analysis demonstrated that sex determines 20.4% of the strength and 7.9% of coordination, as well as age determines 2.6% of overall fitness and 4,3% of strength. Regarding the effects of both sex and age, they determined 22,9% of strength and 7,9% of coordination.

The mediation effect of the test profile of European Fitness Badge (EBF) in the relation between sex and overall fitness, sex and strength, sex and flexibility, as well as in relation between age and overall fitness, age and strength, age and coordination, demonstrate that the exercises in each test profile have a wide applicability, so that the final result obtained reflects the particularities of the individuals, both in terms of gender characteristics and age.

From the above arguments, it can be concluded that this battery of tests - EFB has a wide applicability and can be used successfully in various categories of the population, especially among students, from the profile faculties (physical education and sports) but also for non-profiles (engineering, economics, social sciences, computer science, etc.). All the more so as in Romania, there is no unitary system for evaluating the physical performances of the students from the non-profile faculties, and we consider that the EFB system would be welcome and could apply with real success.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.P.A., V.L.A., C.D., C.B., N.J.H., V.A.G., R.D., C.P., I.I., V.T.G., V.E.U., and G.G.G.; methodology, V.P.A., V.L.A., C.D., C.B., N.J.H., V.A.G., R.D., C.P., I.I., V.T.G., V.E.U., and G.G.G.; software, V.P.A., V.L.A., C.D., C.B., N.J.H., V.A.G., R.D., C.P., I.I., V.T.G., V.E.U., and G.G.G.; validation, V.P.A., V.L.A., C.D., C.B., N.J.H., V.A.G., R.D., C.P., I.I., V.T.G., V.E.U., and G.G.G.; formal analysis, V.P.A., V.L.A., C.D., C.B., N.J.H., V.A.G., R.D., C.P., I.I., V.T.G., V.E.U., and G.G.G.; investigation, V.P.A., V.L.A., C.D., C.B., N.J.H., V.A.G., R.D., C.P., I.I., V.T.G., V.E.U., and G.G.G.; resources, V.P.A., V.L.A., C.D., C.B., N.J.H., V.A.G., R.D., C.P., I.I., V.T.G., V.E.U., and G.G.G.; data curation, V.P.A., V.L.A., C.D., C.B., N.J.H., V.A.G., R.D., C.P., I.I., V.T.G., V.E.U., and G.G.G.; writing—original draft preparation, V.P.A., V.L.A., C.D., C.B., N.J.H., V.A.G., R.D., C.P., I.I., V.T.G., V.E.U., and G.G.G.; writing—review and editing, V.P.A., V.L.A., C.D., C.B., N.J.H., V.A.G., R.D., C.P., I.I., V.T.G., V.E.U., and G.G.G.; visualization, V.P.A., V.L.A., C.D., C.B., N.J.H., V.A.G., R.D., C.P., I.I., V.T.G., V.E.U., and G.G.G.; supervision, V.P.A., V.L.A., C.D., C.B., N.J.H., V.A.G., R.D., C.P., I.I., V.T.G., V.E.U., and G.G.G.; project administration, V.P.A., V.L.A., C.D., C.B., N.J.H., V.A.G., R.D., C.P., I.I., V.T.G., V.E.U., and G.G.G.; funding acquisition, V.P.A., V.L.A., C.D., C.B., N.J.H., V.A.G., R.D., C.P., I.I., V.T.G., V.E.U., and G.G.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. All authors have an equal contribution to the conception and realization of this article.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Aurel Vlaicu University - Faculty of Physical Education and Sport (protocol code 135a/02.03.2021).

Informed Consent Statement

All the individual subjects included in this study provided written informed permission. The University Ethics Commission within the Faculty of Physical Educatikon and sport from Aurel Vlaicu University of Arad noted the following: 1. the authors requested the consent of the subjects involved in the research before carrying out any procedures; 2. the authors have evidence regarding the freely expressed consent of the subjects regarding their participation in this study; 3. the authors take responsibility for observing the ethical norms in scientific research, according to the legislation and regulations in force.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to restrictions eg privacy or ethical. The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to confidentiality.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Penedo, F. J., & Dahn, J. R. Exercise and well-being: a review of mental and physical health benefits associated with physical activity. Current opinion in psychiatry, 2005, 18(2), 189–193. [CrossRef]

- Lawton, E.; Brymer, E.; Clough, P.; Denovan, A. The Relationship between the Physical Activity Environment, Nature Relatedness, Anxiety, and the Psychological Well-being Benefits of Regular Exercisers. Frontiers in psychology 2017, 8, 1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioan, M.R. Systematic review of the impact of physical activity on depression and anxiety symptoms. Journal of Physical Education and Human Movement, 2022, 4(2), 61-68. [CrossRef]

- Stults-Kolehmainen, M.A.; Sinha, R. The Effects of Stress on Physical Activity and Exercise. Sports Med, 2014; 44, 81–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyward, V.H., & Gibson, A.L. Advanced fitness assessment and exercise prescription. Seventh edition. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. 2014, ISBN: 9781492561347.

- Martin, S.A.; Pence, B.D.; Woods, J.A. Exercise and respiratory tract viral infections. Exercise and sport sciences reviews, 2009, 37(4), 157–164. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S.; Tittlbach, S.; Bös, K.; Woll, A. Different Types of Physical Activity and Fitness and Health in Adults: An 18-Year Longitudinal Study. BioMed research international, 2017; 1785217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, J.R., Mood, D., Disch, J.G., & Kang, M. Measurement and evaluation in human performance. Champaign, IL : Human Kinetics. 2016, ISBN: 9781450470438.

- Kyröläinen, H., Santtila, M., Nindl, B.C., & Vasankari, T., Physical fitness profiles of young men: associations between physical fitness, obesity and health. Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 2010, 40(11), 907–920. 2010, 40, 907–920. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y., Lee, P., Lee, T., & Ho, C., Poor Physical Fitness Performance as a Predictor of General Adiposity in Taiwanese Adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2020, 17. [CrossRef]

- Lazăr, A.G., & Leuciuc, F.V., Study Concerning the Physical Fitness of Romanian Students and Its Effects on Their Health-Related Quality of Life. Sustainability, 2021, 13(12), 6821. MDPI AG. Retrieved from. [CrossRef]

- Riebe, D., Ehrman, J.K., Liguori, G., Magal, M., & American College of Sports Medicine (Eds.). ACSM's guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. Wolters Kluwer. 2018, ISBN: 9781975150228.

- Marin, A.; Stefanica, V.; Rosculet, I. Enhancing Physical Fitness and Promoting Healthy Lifestyles in Junior Tennis Players: Evaluating the Influence of “Plyospecific” Training on Youth Agility. Sustainability, 2023, 15(13), 9925. [CrossRef]

- Badau, D., Badau, A., Joksimović, M., Oancea, B.M., Manescu, C.O., Graur, C., ... & Silisteanu, S.C. The ef-fects of 6-weeks program of physical therapeutic exergames on cognitive flexibility focused by reaction times in relation to manual and podal motor abilities. Balneo & PRM Research Journal, 2023, 14(3).

- Galea, I., Negru, D., Ardelean, V.P., Dulceanu, C., & Olariu, I.,Students' job-related physical condition. How fit are they? Timisoara Physical Education & Rehabilitation Journal, 2017, 10, 33–37. [CrossRef]

- Orland, Y., Beeri, M.S., Levy, S., Israel, A., Ravona-Springer, R., Segev, S., & Elkana, O., Physical fitness mediates the association between age and cognition in healthy adults. Aging clinical and experimental research, 2021, 33(5), 1359–1366. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, H., Singh, T., Arya, Y.K., & Mittal, S., Physical Fitness and Exercise During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Enquiry. Frontiers in psychology, 2020, 11, 590172. [CrossRef]

- Vancini, R.L., Andrade, M.S., Viana, R.B., Nikolaidis, P.T., Knechtle, B., Campanharo, C., de Almeida, A.A., Gentil, P., & de Lira, C., Physical exercise and COVID-19 pandemic in PubMed: Two months of dynamics and one year of original scientific production. Sports medicine and health science, 2021, 3(2), 80–92. [CrossRef]

- Ai, X., Yang, J., Lin, Z., & Wan, X., Mental Health and the Role of Physical Activity During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Frontiers in psychology, 2021; 12, 759987. [CrossRef]

- Michigan Medicine. (n.d.). Importance of Physical Activity and Exercise during the COVID-19. Psychiatry. Retrieved January 3, 2022, from: https://medicine.umich.edu/dept/psychiatry/michigan-psychiatry-resources-covid-19/your-lifestyle/importance-physical-activity-exercise-during-covid-19-pandemic.

- Osipov, A.Y., Ratmanskaya, T.I., Zemba, E.A., Potop, V., Kudryavtsev, M.D., & Nagovitsyn, R.S., The impact of the universities closure on physical activity and academic performance in physical education in university students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Physical education of students, 2021, 25(1), 20-27. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T., Nguyen, M.H., Pham, T., Le, V.T., Nguyen, T.T., Luong, T.C., Do, B.N., Dao, H.K., Nguyen, H.C., Ha, T.H., Pham, L.V., Nguyen, P.B., Nguyen, H., Do, T.V., Nguyen, H.Q., Trinh, M.V., Le, T.T., Tra, A.L., Nguyen, T., Nguyen, K.T., … Duong, T.V., Negative Impacts of COVID-19 Induced Lockdown on Changes in Eating Behavior, Physical Activity, and Mental Health as Modified by Digital Healthy Diet Literacy and eHealth Literacy. Frontiers in nutrition, 2021, 8, 774328. [CrossRef]

- Ammar, A., Brach, M., Trabelsi, K., Chtourou, H., Boukhris, O., Masmoudi, L., Bouaziz, B., Bentlage, E., How, D., Ahmed, M., Müller, P., Müller, N., Aloui, A., Hammouda, O., Paineiras-Domingos, L.L., Braakman-Jansen, A., Wrede, C., Bastoni, S., Pernambuco, C.S., Mataruna, L., … Hoekelmann, A., Effects of COVID-19 Home Confinement on Eating Behaviour and Physical Activity: Results of the ECLB-COVID19 International Online Survey. Nutrients 2020, 12(6), 1583. [CrossRef]

- Antunes, R., & Frontini, R., Physical activity and mental health in Covid-19 times: an editorial. Sleep medicine, 2021, 77, 295–296. [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, L., Shaw, K.A., Ko, J., Deprez, D., Chilibeck, P.D., & Zello, G.A.,The impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on university students' dietary intake, physical activity, and sedentary behaviour. Applied physiology, nutrition, and metabolism = Physiologie appliquee, nutrition et metabolisme, 2021, 46, 265–272.

- Massiera, B., Petracovschi, S., & Jessica, C., Ideological challenges to developing leisure sport in Romania: a cultural and historical analysis of the impact of elite sport on popular sport practice. Loisir et Société/Society and Leisure, 2021, 36(1), 111-126. [CrossRef]

- Fagaras, S.P., Radu, L.E., & Vanvu, G.,The level of physical activity of university students. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 2015, 197, 1454–1457. [CrossRef]

- Leuciuc, F.V.; Ghervan, P.; Popovici, I.M.; Benedek, F.; Lazar, A.G.; Pricop, G. Social and Educational Sustainability of the Physical Education of Romanian Students and the Impact on Their Physical Activity Level. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyori, F.; Berki, T.; Katona, Z.; Vári, B.; Katona, Z.; Petrovszki, Z., Physical Activity in the Southern Great Plain Region of Hungary: The Role of Sociodemographics and Body Mass Index. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, 2021, 18, 12414. [CrossRef]

- Haverkamp, B.F., Wiersma, R., Vertessen, K., van Ewijk, H., Oosterlaan, J., & Hartman, E., Effects of physical activity interventions on cognitive outcomes and academic performance in adolescents and young adults: A meta-analysis. Journal of sports sciences 2020, 38(23), 2637–2660. [CrossRef]

- Suni, J.H., Oja, P., Laukkanen, R.T., Miilunpalo, S.I., Pasanen, M.E., Vuori, I.M., Vartiainen, T.M., & Bös, K., Health-related fitness test battery for adults: aspects of reliability. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation, 1996, 77, 399–405. [CrossRef]

-

Fitnessgram by the Cooper Institute. FitnessGram by The Cooper Institute. (n.d.). (Accesed December 25, 2021), from https://fitnessgram.net/.

- Wood, R., (2008). Eurofit Fitness Test Battery. Topend Sports Website, https://www.topendsports.com/testing/eurofit.html , (Accessed December 24, 2021).

- Hoffman, J., Norms for fitness, performance, and health. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. 2006, ISBN: 978-0736054836.

- Simonton, K.L., Mercier, K., & Garn, A.C., Do fitness test performances predict students’ attitudes and emotions toward physical education? Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 2019, 24, 549–564. [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, G.B. Dwyer, G.B., Davis, S.E., American College of Sports Medicine., & American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM's health-related physical fitness assessment manual. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2008, ISBN: 978-07817-7549-6.

- Klemm, K.; Krell-Roesch, J.; De Clerck, I.L.; Brehm, W.; Boes, K. Health-Related Fitness in Adults From Eight European Countries-An Analysis Based on Data From the European Fitness Badge. Frontiers in physiology, 2021, 11, 615237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klemm, K., Brehm, W., & Bös, K., The European Fitness Badge as a diagnostic instrument for the HEPA concept: Development and evaluation. Leipziger sportwissenschaftliche Beiträge, 2017, 58(2), pp. S. 83-105.

- Martin, B.W., Kahlmeier, S., Racioppi, F. et al. Evidence-based physical activity promotion - HEPA Europe, the European Network for the Promotion of Health-Enhancing Physical Activity. J Public Health, 2006 14, 53–57. [CrossRef]

- Bös, K., Brehm, W., Klemm, K., Schreck, M., and Pauly, P., European Fitness Badge. Handbook for Instructors. Available online at: https://fitness-badge.eu/ wp- content/uploads/2017/03/EFB-Instructors- Handbook-EN.pdf (accessed December 25, 2021).

- Hayes, A.F., Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press; 2013, ISBN: 978-1609182304.

- Muntean, R.I., Ștefănică, V., Ursu, V.E., Rusu, R.G., Man, C.M., Tomuș, A.M.,... & Roșu, D. The Impact of HVLA Manipulations and Therapeutic Massage in Increasing the Mobility of the Lateral Flexion of the Neck. BRAIN. Broad Research in Artificial Intelligence and Neuroscience, 2023, 14(4), 266-291. [CrossRef]

- Ioan, M.R. Handball player's recovery after the injury of the anterior cruciate ligament. Sport & Socie-ty/Sport si Societate, 2021, (2). [CrossRef]

- Carson, V., Hunter, S., Kuzik, N., Gray, C.E., Poitras, V.J., Chaput, J.P., ... & Tremblay, M.S., Systematic review of sedentary behaviour and health indicators in school-aged children and youth: an update. Applied physiology, nutrition, and metabolism, 2016, 41(6), S240-S265. [CrossRef]

- Nyenhuis, S.M.; Greiwe, J.; Zeiger, J.S.; Nanda, A.; Cooke, A. Exercise and Fitness in the Age of Social Distancing During the COVID-19 Pandemic. The journal of allergy and clinical immunology. In practice, 2020, 8(7), 2152–2155. [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, M.J., Pasini, M., De Dominicis, S., & Righi, E. (2020). Physical activity: Benefits and challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports, 2020, 30(7), 1291–1294. [CrossRef]

- WHO. Stay physically active during self-quarantine. Available at: http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/coronavirus-covid-19/novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov-technical-guidance/stay-physically-active-during-self-quarantine (Accesed December 24, 2021).

- Roșu, D., Enache, S., Ștefănică, V., & Muntean, R.I. Initiation in Kin Ball – Pre and Post Pandemic Effects on Hand Strength, Resistance and Coordination, 2023. Preprints.

- Stockwell, S., Trott, M., Tully, M., Shin, J., Barnett, Y., Butler, L. & Smith, L., Changes in physical activity and sedentary behaviours from before to during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown: a systematic review. BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine, 2021, 7(1), e000960. [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Mao, L.; Nassis, G.P.; Harmer, P.; Ainsworth, B.E.; Li, F. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): The need to maintain regular physical activity while taking precautions. Journal of sport and health science, 2020, 9, 103–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, M., Zhang, S., & An, R., Effectiveness of A Body Shape Index (ABSI) in predicting chronic diseases and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity reviews : an official journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity, 2018, 19(5), 737–759. [CrossRef]

- Krakauer, N.Y., & Krakauer, J.C., Expansion of waist circumference in medical literature: potential clinical application of a body shape index. J Obes Weight Loss Ther, 2014, 4(216), 2. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Bokariya, P.; Kothari, R. A body shape index (ABSI) - is it time to replace body mass index? International Journal of Research and Review. 2020, 7(9): 303-312.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).