Submitted:

15 January 2024

Posted:

16 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Methods

Study area, design and period

Study population

Sample size and sampling procedure

Variables

Operational definitions

Data collection tool and procedure

Data quality control

Data processing and analysis

Results

Demographic and educational characteristics of the participants (N=589)

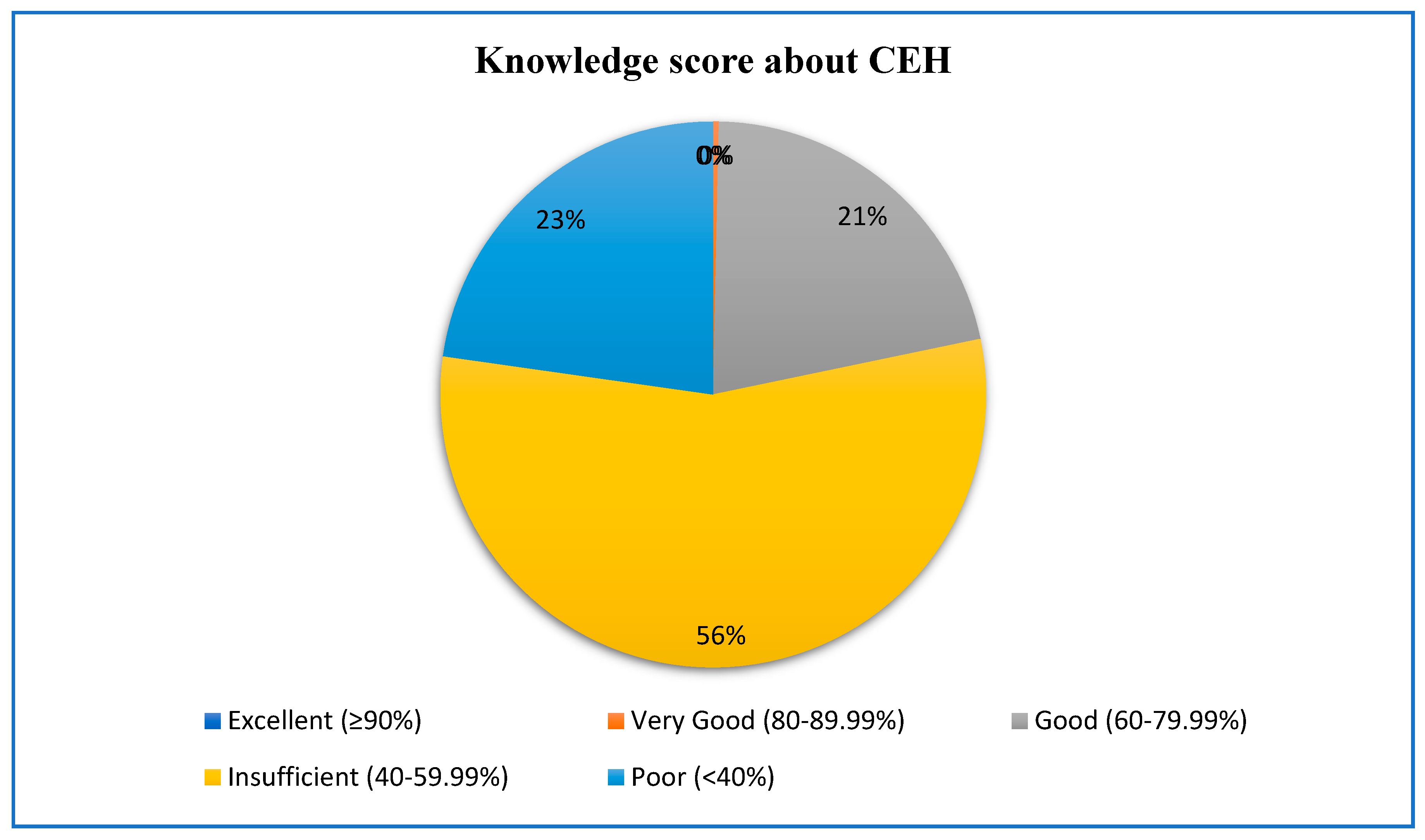

Knowledge of the nursing students about children’s environmental health (N=589)

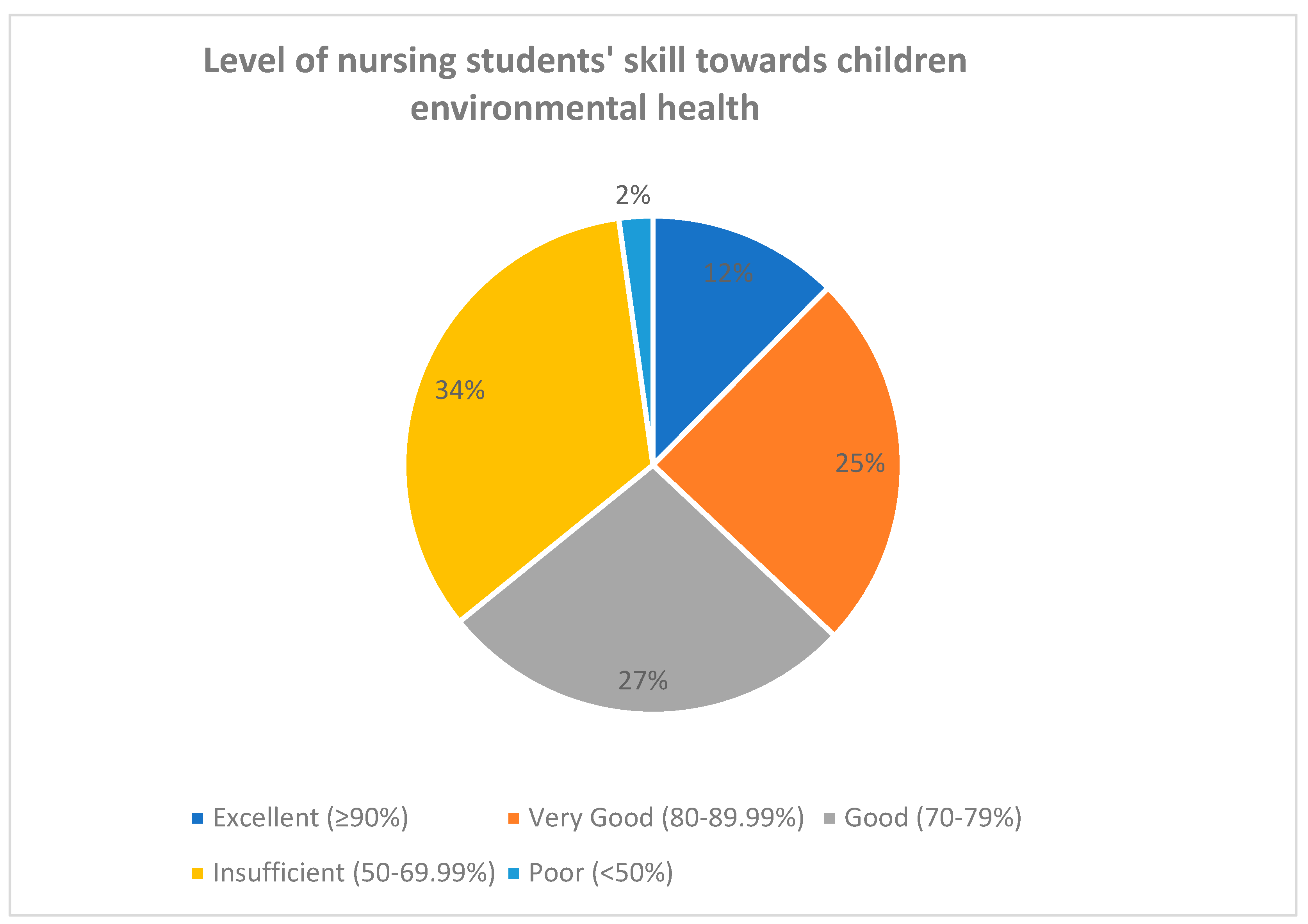

Skills towards children’s environmental health

Predictors of nursing students’ knowledge and skill in children’s environmental health

Discussion

Limitations of the study

Conclusion

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Goldman RH, Zajac L, Geller RJ, Miller MD. Developing and implementing core competencies in children’s environmental health for students, trainees and healthcare providers: a narrative review. BMC medical education. 2021;21(1):503. [CrossRef]

- Landrigan PJ. Environmental hazards for children in USA. International journal of occupational medicine and environmental health. 1998;11(2):189-94.

- Lilly Evie DM. Environmental Influences on Child Development. 2022.

- Ramos FM, Herrera MT, Zajac L, Sheffield PJANR. Children’s environmental health and disaster resilience in Puerto Rico and the US Virgin Islands. 2022;66:151482. [CrossRef]

- Sattler B, Davis del BA. Nurses’ role in children’s environmental health protection. Pediatric nursing. 2008;34(4):329-39.

- Engström M, Randell E, Lucas S. Child health nurses’ experiences of using the Safe Environment for Every Kid (SEEK) model or current standard practice in the Swedish child health services to address psychosocial risk factors in families with young children – A mixed-methods study. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2022;132:105820. [CrossRef]

- Marilyn J. Hockenberry DW. Wong's Nursing Care of Infants and Children - E-Book: Wong's Nursing Care of , 11th edition. 2019.

- Álvarez-García C, Álvarez-Nieto C, Sanz-Martos S, Puente-Fernández D, López-Leiva I, Gutiérrez-Puertas L, et al. Undergraduate Nursing Students’ Attitudes, Knowledge, and Skills Related to Children’s Environmental Health. The Journal of nursing education. 2019;58(7):401-8.

- Álvarez-García C, Álvarez-Nieto C, Carter R, Kelsey J, Sanz-Martos S, López-Medina IM. Cross-cultural adaptation of children’s environmental health questionnaires for nursing students in England. Health Education Journal. 2020;79(7):826-38. [CrossRef]

- Jakšić K, Sarić MM, Čulin JJJoHR. Nursing students’ knowledge and attitudes regarding brominated flame retardants from three Croatian universities. 2020;36(2):289-99. [CrossRef]

- Association APH. "Protecting the Health of Children: A National Snapshot of Environmental Health Services". 2019.

- Moeller DW. Environmental health: Harvard University Press; 2011.

- UNICEF. Health Environements for Healthy Children: Global Programme Framework. 2021.

- Wigle DT, Arbuckle TE, Walker M, Wade MG, Liu S, Krewski D. Environmental Hazards: Evidence for Effects on Child Health. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part B. 2007;10(1-2):3-39. [CrossRef]

- Etzel RA. Environmental risks in childhood. SLACK Incorporated Thorofare, NJ; 2004. p. 431-6. [CrossRef]

- Prevention CfDCa. National Environmental Public Health Tracking. 2022.

- Medgyesi DN, Brogan JM, Sewell DK, Creve-Coeur JP, Kwong LH, Baker KK. Where Children Play: Young Child Exposure to Environmental Hazards during Play in Public Areas in a Transitioning Internally Displaced Persons Community in Haiti. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2018;15(8):1646. [CrossRef]

- Pronczuk J, Surdu S. Children’s Environmental Health in the Twenty-First Century: Challenges and Solutions. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2008;1140(1):143-54. [CrossRef]

- Goals UUNSD.

- Organization WH. Ambient air pollution: A global assessment of exposure and burden of disease. 2016.

- Organization WH. More than 90% of the world’s children breathe toxic air every day. 2018.

- Rees N, Fuller R. The toxic truth: children’s exposure to lead pollution undermines a generation of future potential: UNICEF; 2020.

- Official Records of the General Assembly F-ts, Realizing the rights of the child through a healthy, environment: Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights AH. 2020.

- Vilcins D, Sly PD, Jagals P. Environmental risk factors associated with child stunting: a systematic review of the literature. Annals of global health. 2018;84(4):551. [CrossRef]

- Organization WH. Information sheet on children’s environmental health for clinicians: pollution-free environments for healthy generations: what every clinician needs to know about children’s environmental health. World Health Organization, 2022.

- AnAaker A, Nilsson M, Holmner A, Elf M. Nurses’ perceptions of climate and environmental issues: A qualitative study. Journal of advanced nursing. 2015;71(8):1883-91. [CrossRef]

- Sattler B, Davis ADB, Pike-Paris A. Nurses’ role in children’s environmental health protection. Pediatric Nursing. 2008;34(4).

- Leffers J, Levy RM, Nicholas PK, Sweeney CF. Mandate for the nursing profession to address climate change through nursing education. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2017;49(6):679-87. [CrossRef]

- Goldman RH, Zajac L, Geller RJ, Miller MD. Developing and implementing core competencies in children’s environmental health for students, trainees and healthcare providers: a narrative review. BMC medical education. 2021;21(1):503. [CrossRef]

- Landrigan PJ. Environmental hazards for children in USA. International journal of occupational medicine and environmental health. 1998;11(2):189-94.

- Lilly Evie DM. Environmental Influences on Child Development. 2022.

- Ramos FM, Herrera MT, Zajac L, Sheffield PJANR. Children’s environmental health and disaster resilience in Puerto Rico and the US Virgin Islands. 2022;66:151482. [CrossRef]

- Sattler B, Davis del BA. Nurses’ role in children’s environmental health protection. Pediatric nursing. 2008;34(4):329-39.

- Engström M, Randell E, Lucas S. Child health nurses’ experiences of using the Safe Environment for Every Kid (SEEK) model or current standard practice in the Swedish child health services to address psychosocial risk factors in families with young children – A mixed-methods study. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2022;132:105820. [CrossRef]

- Marilyn J. Hockenberry DW. Wong's Nursing Care of Infants and Children - E-Book: Wong's Nursing Care of , 11th edition. 2019.

- Álvarez-García C, Álvarez-Nieto C, Sanz-Martos S, Puente-Fernández D, López-Leiva I, Gutiérrez-Puertas L, et al. Undergraduate Nursing Students’ Attitudes, Knowledge, and Skills Related to Children’s Environmental Health. The Journal of nursing education. 2019;58(7):401-8.

- Álvarez-García C, Álvarez-Nieto C, Carter R, Kelsey J, Sanz-Martos S, López-Medina IM. Cross-cultural adaptation of children’s environmental health questionnaires for nursing students in England. Health Education Journal. 2020;79(7):826-38. [CrossRef]

- Jakšić K, Sarić MM, Čulin JJJoHR. Nursing students’ knowledge and attitudes regarding brominated flame retardants from three Croatian universities. 2020;36(2):289-99. [CrossRef]

| Variables | Category | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (24.76±4.97) (years) | 20-26 | 440 | 74.8% |

| >26 | 149 | 25.3% | |

| Gender | Male | 311 | 52.8 |

| Female | 278 | 47.2 | |

| Study year | First-year | 54 | 9.2 |

| Second-year | 8 | 1.4 | |

| Third-year | 406 | 68.9 | |

| Fourth-year | 121 | 20.5 | |

| Study program | Comprehensive nursing | 455 | 77.2 |

| Specialty nursing | 134 | 22.8 | |

| Received training/lecture about CEH | Yes | 373 | 63.3 |

| No | 216 | 36.7 |

| Items | Correctly answered (%) |

|---|---|

| 1. The pediatric population is more susceptible to environmental threats due to their biological immaturity*. | 167 (28.4) |

| 2. The increased energy and metabolic consumption of the pediatric population protects children from environmental hazards. | 167 (28.4) |

| 3. The higher rate of cell growth during the pediatric age increases the risk of health effects caused by environmental factors*. | 256(43.5) |

| 4. Environmental factors do not influence hormonal secretion during puberty. | 394(66.9) |

| 5. Nitrogen oxide from fossil fuels in the home and tobacco smoke causes redness and burns on the skin. | 134(22.8) |

| 6. Particles from animals exacerbate asthma crisis*. | 481(81.7) |

| 7. Increased humidity at home improves respiratory diseases in children. | 481(81.7) |

| 8. Passive smoking is associated with the development of acute leukemia in children*. | 345(58.6) |

| 9. Childhood leukemia incidence rates are higher in the areas most exposed to radon*. | 274(46.5) |

| 10. Overexposure to solar ultraviolet radiations can damage the skin of adults more severely than that of children. | 291(49.4) |

| 11. During childhood more than half of the expected lifetime solar ultraviolet radiation is absorbed*. | 326(55.3) |

| 12. Lead accumulates in the body affecting the nervous system*. | 348(59.1) |

| 13. Chronic dietary exposure to mercury (fish and shellfish) is less toxic to children’s central nervous system than to adults. | 258(43.8) |

| 14. Exposure to pesticides increases the risk of developing attention deficit problems in school-aged children*. | 356(60.4) |

| 15. Children born to smoking mothers during pregnancy are at risk of lower intellectual capacity*. | 469(79.6) |

| 16. Exposure to organic solvents during fetal development can cause learning disabilities in children*. | 351(59.6) |

| 17. Water containing nitrates can only cause intoxication during childhood. | 330(56.0) |

| 18. Chlorination of water forms sub-products from the disinfection process that have been classified as carcinogenic*. | 188(31.9) |

| 19. The major source of childhood exposure to pesticides is through ambient air. | 194(32.9) |

| 20. The main route of exposure to mercury is through cereal intake. | 295(50.1) |

| 21. Exposure to lead through diet occurs mainly through fish intake. | 287(48.7) |

| 22. Food colorings and preservatives are associated with central nervous system problems*. | 256(43.5) |

| 23. Genetically modified foods cause fewer allergic reactions in children. | 170(28.9) |

| 24. Schools and nurseries are environmentally safe places. | 97(16.5) |

| 25. Children are exposed to higher concentrations of air pollutants at home than outdoors. | 298(50.6) |

| 26. Parks and gardens are the areas with the least environmental pollutants where children can play. | 72(12.2) |

| Items | Responses for items | ||||

| SDA | DA | N | AG | SA | |

| 1. I am able to assess the main environmental risks to which a child is exposed. | 45 (7.6) | 37(6.3) | 26(4.4) | 316(53.7) | 165(28.0) |

| 2. I am NOT able to identify the environmental risks that can cause respiratory diseases in a child. | 180(30.6) | 239(40.6) | 59(10.0) | 62(10.5) | 49(8.3) |

| 3. I am able to identify the environmental risks that can cause neoplastic diseases in a child. | 60(10.2) | 108(18.3) | 89(15.1) | 238(40.4) | 94(16.0) |

| 4. I am NOT able to identify the environmental risks that can cause neurological disorders in a child. | 101(17.1) | 220(37.4) | 85(14.4) | 137(23.3) | 46(7.8) |

| 5. I am able to provide health education to parents about the main contaminants in their child’s food. | 48(8.1) | 36(6.1) | 38(6.5) | 258(43.8) | 209(35.5) |

| 6. I am NOT able to identify the environmental risks in playgrounds. | 204(34.6) | 223(37.9) | 53(9.0) | 61(10.4) | 48(8.1) |

| 7. I am able to provide health education to parents about actions to minimize environmental risks to which a child is exposed when playing outdoors. | 60(10.2) | 51(8.7) | 35(5.9) | 229(38.9) | 214(36.3) |

| 8. I am NOT able to identify the environmental risks in a child’s home. | 199(33.8) | 213(36.2) | 54(9.2) | 66(11.2) | 57(9.7) |

| 9. I am able to provide health promotion to parents about environmental risks at home. | 55(9.3) | 65(11.0) | 40(6.8) | 237(40.2) | 192(32.6) |

| 10. I am able to identify the environmental risks in a child’s school. | 48(8.1) | 53(9.0) | 34(5.8) | 244(41.4) | 210(35.7) |

| 11. I am NOT able to identify the actions needed to combat environmental risks in a child’s school. | 191(32.4) | 224(38.0) | 57(9.7) | 67(11.4) | 50(8.5) |

| 12. I do not feel able to do my job as a nurse in a Paediatrics Environmental Health Specialty Unit. | 150(25.5) | 193(32.8) | 62(10.5) | 120(20.4) | 64(10.9) |

| Predictors of nursing students’ knowledge about CEH | ||||||

| Variables | Category | B | P-value | Exp(B) | CI 95% | |

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Gender | Male | 0.182 | 0.269 | 1.199 | 0.869 | 1.656 |

| Female | 0a | . | 1 | . | ||

| Year of study | First-year | -0.305 | 0.412 | 0.737 | 0.355 | 1.529 |

| Second-year | 0.078 | 0.913 | 1.081 | 0.267 | 4.382 | |

| Third-year | -0.405 | 0.050 | 0.667 | 0.445 | 1.001 | |

| Fourth year | 0a | . | 1 | . | ||

| Received training /lecture about CEH | Yes | 0.112 | 0.604 | 1.119 | 0.732 | 1.710 |

| No | 0a | . | 1 | . | ||

| Nursing study type | Comprehensive | -0.275 | 0.244 | 0.759 | 0.478 | 1.206 |

| Specialty | 0a | . | 1 | . | ||

| Age | Age | 0.060 | 0.001 | 1.061 | 1.024 | 1.100 |

| Skills of students | Attitude score | 0.026 | 0.016 | 1.027 | 1.005 | 1.048 |

| Predictors of nursing students’ skills about CEH | ||||||

| Gender | Male | 0.513 | 0.001 | 1.671 | 1.236 | 2.257 |

| Female | 0a | 1 | . | |||

| Year of study | First-year | 0.496 | 0.152 | 1.642 | 0.833 | 3.238 |

| Second-year | -0.927 | 0.178 | 0.396 | 0.103 | 1.525 | |

| Third-year | 0.078 | 0.686 | 1.081 | 0.741 | 1.576 | |

| Fourth year | 0a | . | 1 | . | ||

| Received training/ lecture about CEH | Yes | -0.105 | 0.608 | 0.900 | 0.601 | 1.347 |

| No | 0a | . | 1 | . | ||

| Nursing study type | Comprehensive | 0.117 | 0.595 | 1.124 | 0.730 | 1.731 |

| Specialty | 0a | 1 | ||||

| Age | Age | 0.054 | 0.002 | 1.056 | 1.020 | 1.092 |

| Knowledge of students | knowledge score | 0.059 | 0.016 | 1.060 | 1.011 | 1.112 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).