Submitted:

15 January 2024

Posted:

16 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Chronic kidney disease and its impact

1.2. Emotional intelligence

1.3. Quality of life in patients undergoing chronic hemodialysis therapy

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Aims

2.2. Methods

2.3. Study design

2.4. Participants

2.5. Data Collection

2.6. Variables

2.7. Instruments

2.8. Statistical analysis

2.9. Ethical considerations

3. Results

3.1. Study sample characteristics

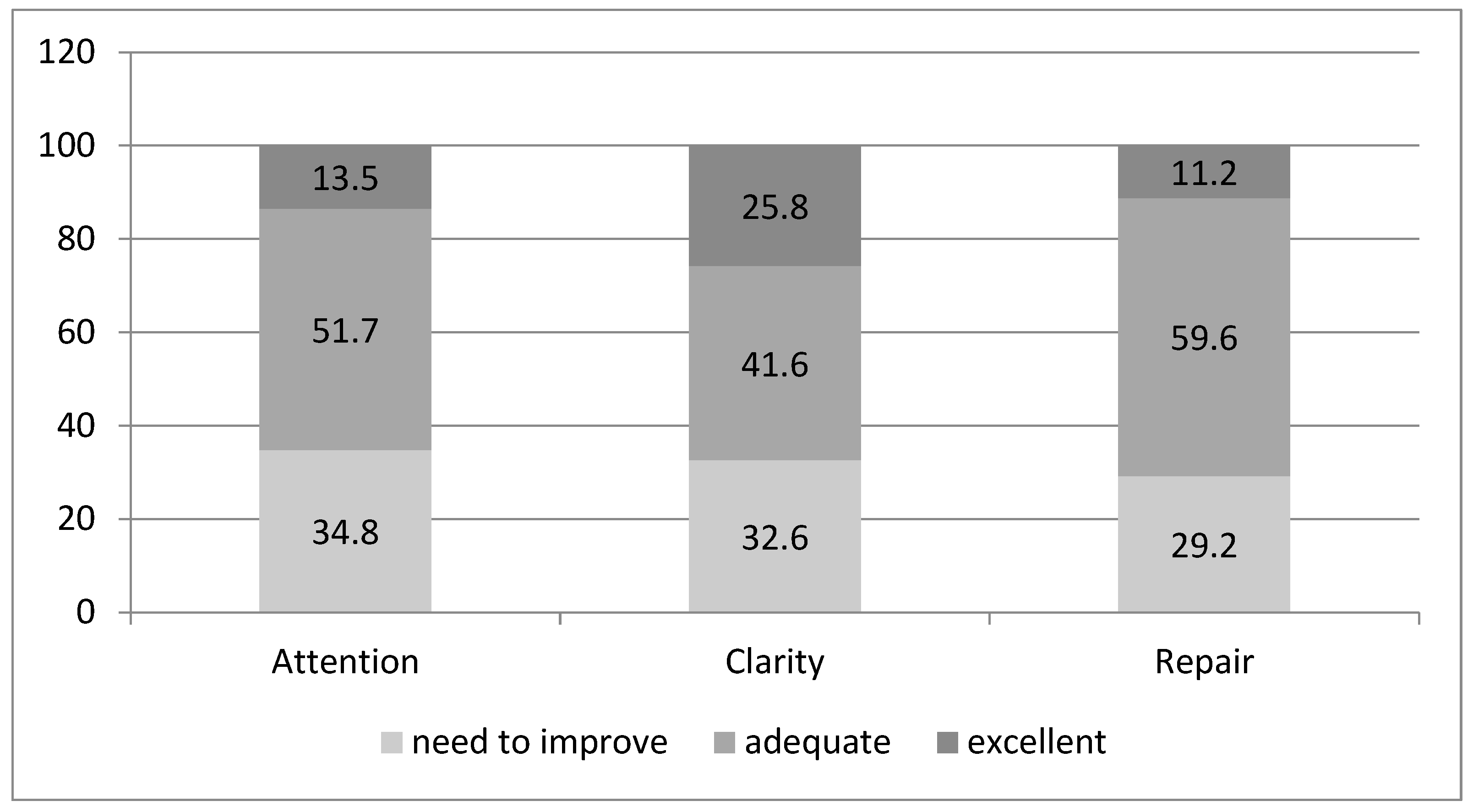

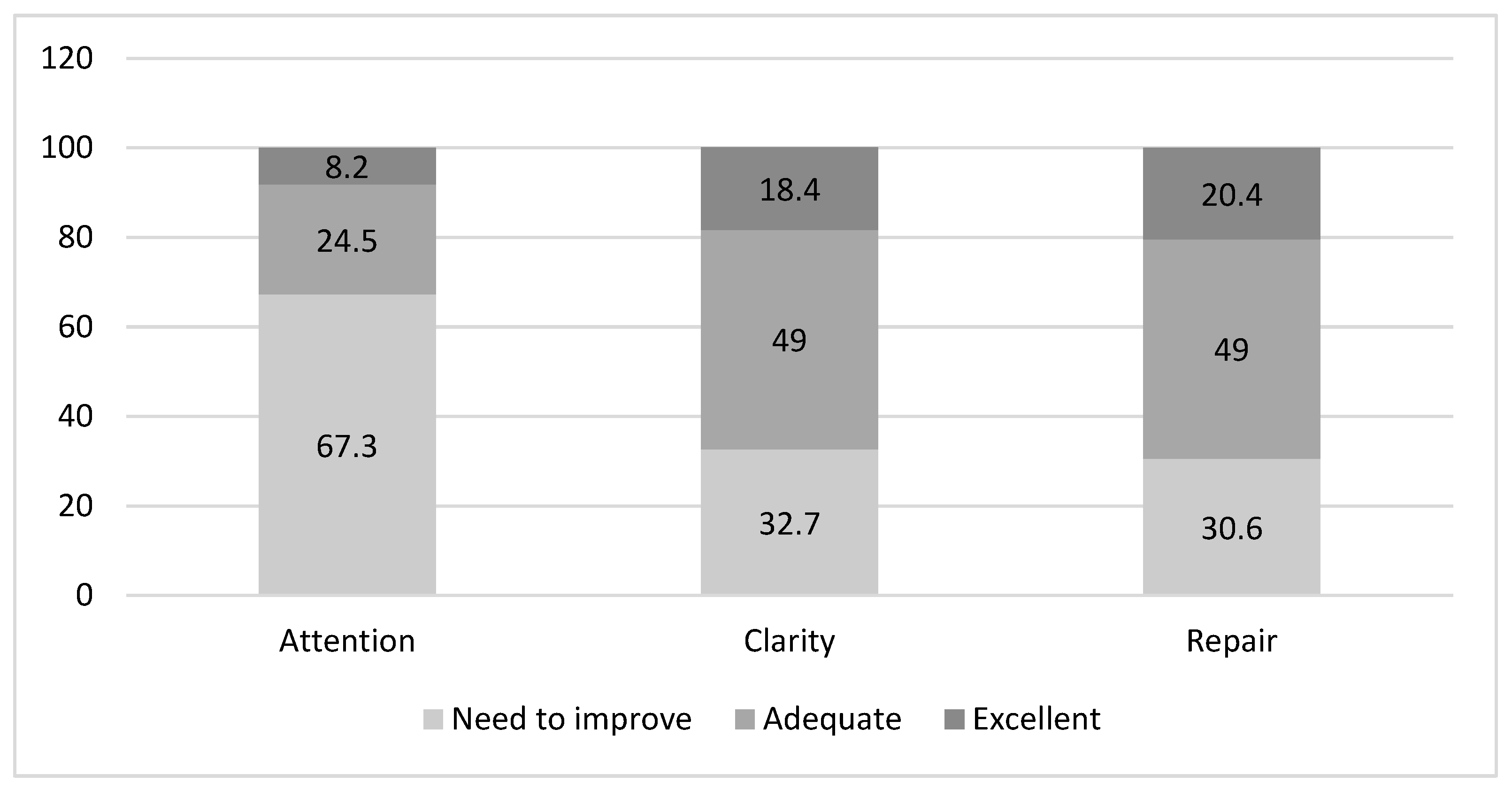

3.2. Emotional Intelligence in chronic hemodialysis patients

3.3. Quality of life in chronic hemodialysis patients

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

List of Abbreviations

| HD | hemodialysis |

| TMMS-24 | Trait meta-mood scale |

| KDQOL-SF | Kidney disease quality of life-short form questionnaire |

| CDK | Chronic kidney disease |

| QL | Quality of life |

| EI | Emotional intelligence |

| SPSS | Statistical package for social sciences |

| IBM | International business machines corporation |

| IQR | Inter quartile rang |

| COPD | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

References

- Lv, J.C.Z.L. Prevalence and Disease Burden of Chronic Kidney Disease. In Mechanisms and Therapies Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Fibrosis, R., Liu, B.C., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Webster, A.C.; Nagler, E.V.; Morton, R.L.; Masson, P. Chronic Kidney Disease. Lancet 2017, 389, 1238–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, N.R.; Fatoba, S.T.; Oke, J.L.; Hirst, J.A.; O’Callaghan, C.A.; Lasserson, D.S.; Hobbs, F.D.R. Global prevalence of chronic kidney disease–A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2016, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckardt, K.U.; Coresh, J.; Devuyst, O.; Johnson, R.J.; Köttgen, A.; Levey, A.S.; et al. Evolving importance of kidney disease: From subspecialty to global health burden. Lancet 2013, 382, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, B.; Wulf, S.; Bikbov, B.; Perico, N.; Cortinovis, M.; De Vaccaro, K.C.; et al. Maintenance dialysis throughout the world in years 1990 and 2010. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015, 26, 2621–2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liyanage, T.; Ninomiya, T.; Jha, V.; Neal, B.; Patrice, H.M.; Okpechi, I.; et al. Worldwide access to treatment for end-stage kidney disease: A systematic review. Lancet 2015, 385, 1975–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikbov, B.; Purcell, C.A.; Levey, A.S.; Smith, M.; Abdoli, A.; Abebe, M.; et al. Global, regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2020, 395, 709–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.; Flythe, J.E.; Allon, M. Dialysis Care around the World: A Global Perspectives Series. Kidney360 2021, 2, 604–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pabón-Varela, Y.; Paez-Hernandez, K.S.; Rodriguez-Daza, K.D.; Medina-Atencia, C.E.; López-Tavera, M.; Salcedo-Quintero, L.V. Calidad de vida del adulto con insuficiencia renal crónica, una mirada bibliográfica. Duazary 2015, 12, 157. Available online: https://revistas.unimagdalena.edu.co/index.php/duazary/article/view/1473/922 (accessed on 18 December 2020). [CrossRef]

- Fleishman, T.T.; Dreiher, J.; Shvartzman, P. Pain in Maintenance Hemodialysis Patients: A Multicenter Study. J Pain Symptom Manage 2018, 56, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grams, M.E.; Yang, W.; Rebholz, C.M.; Wang, X.; Porter, A.C.; Inker, L.A.; et al. Risks of Adverse Events in Advanced CKD: The Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017, 70, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perl, J.; Karaboyas, A.; Morgenstern, H.; Sen, A.; Rayner, H.C.; Vanholder, R.C.; et al. Association between changes in quality of life and mortality in hemodialysis patients: Results from the DOPPS. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2017, 32, 521–527. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/ndt/article/32/3/521/3060597 (accessed on 23 December 2020). [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Berrocal, P.; Extremera, N. Emotional intelligence: A theoretical and empirical review of its first 15 years of history. Psycothema 2006, 18, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, P.J.; Hill, A.; Kaya, M.; Martin, B. The measurement of emotional intelligence: A critical review of the literature and recommendations for researchers and practitioners. Front Psychol. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salovey, P.; Mayer, J.D.; Goldman, S.; Turvey, C.; Palfai, T. Emotional attention, clarity and repair: exploring emotional intelligence using the Trait Meta-Mood Scale. In Emotion, Disclosure, and Health; Pennebaker, J.W., Ed.; Washington, DC, USA, 1995; pp. 125–154. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, J.; Salovey, P.; Caruso, D. Models of Emotional Intelligence; R. J. S. Cambridge University Press, 2000; pp. 396–420. [Google Scholar]

- Guil, R.; Ruiz-González, P.; Merchán-Clavellino, A.; Morales-Sánchez, L.; Zayas, A.; Gómez-Molinero, R. Breast Cancer and Resilience: The Controversial Role of Perceived Emotional Intelligence. Front Psychol. 2020, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, D.R.; Mayer, J.D.; Bryan, V.; Phillips, K.G.; Salovey, P. Measuring emotional and personal intelligence. In Positive Psychological Assessment: A Handbook of Models and Measures; Gallagher, M.W., Lopez, S.J., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; pp. 233–245. [Google Scholar]

- Sarrionandia, A.; Mikolajczak, M. A meta-analysis of the possible behavioural and biological variables linking trait emotional intelligence to health. Heal Psychol Rev. 2020, 14, 220–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, F.; Tourani, S.; Ziapour, A.; Abbas, J.; hematti, M.; Moghadam, E.J.; et al. Emotional Intelligence and Quality of Life in Elderly Diabetic Patients. Int Q Community Health Educ. 2021, 42, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, A.; Ramalho, N.; Morin, E. A comprehensive meta-analysis of the relationship between Emotional Intelligence and health. Pers Individ Dif 2010, 49, 554–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kret, M.E.; De Gelder, B. A review on sex differences in processing emotional signals. Neuropsychologia 2012, 50, 1211–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hines, M. Neuroscience and sex/gender: Looking back and forward. J Neurosci. 2020, 40, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joel, D.; Berman, Z.; Tavor, I.; Wexler, N.; Gaber, O.; Stein, Y.; et al. Sex beyond the genitalia: The human brain mosaic. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2015, 112, 15468–15473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahnavazi, Masoome, Zohreh Parsa Yekta FR and MSY. The Relationship between Emotional Intelligence and Quality of life among University Teachers. Int J Med Res Heal Sci. 2016, 5, 564–570. [Google Scholar]

- Shahnavazi, M.; Parsa-Yekta, Z.; Yekaninejad, M.S.; Amaniyan, S.; Griffiths, P.; Vaismoradi, M. The effect of the emotional intelligence education programme on quality of life in haemodialysis patients. Appl Nurs Res. 2018, 39, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jesus, N.M.; Souza GF de Mendes-Rodrigues, C.; Almeida Neto OP de Rodrigues, D.D.M.; Cunha, C.M. Quality of life of individuals with chronic kidney disease on dialysis. J Bras Nefrol. 2019, 41, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The WHOQOL Group. Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. Psychol Med. 1998, 28, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jassal, S.V.; Karaboyas, A.; Comment, L.A.; Bieber, B.A.; Morgenstern, H.; Sen, A.; et al. Functional Dependence and Mortality in the International Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). Am J Kidney Dis. 2016, 67, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perales-Montilla, C.M.; Duschek, S.; Reyes-del Paso, G.A. Influencia de los factores emocionales sobre el informe de síntomas somáticos en pacientes en hemodiálisis crónica: relevancia de la ansiedad. Nefrologia 2013, 33, 816–825. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Palmer, S.; Vecchio, M.; Craig, J.C.; Tonelli, M.; Johnson, D.W.; Nicolucci, A.; et al. Prevalence of depression in chronic kidney disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Kidney Int 2013, 84, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanaugh, K.L. Patient Experience Assessment is a Requisite for Quality Evaluation: A Discussion of the In-Center Hemodialysis Consumer Assessment of Health Care Providers and Systems (ICH CAHPS) Survey. Semin Dial. 2016, 29, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kliger, A.S. Quality measures for dialysis: Time for a balanced scorecard. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016, 11, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuasuwan, A.; Chuasuwan, A.; Pooripussarakul, S.; Thakkinstian, A.; Ingsathit, A.; Ingsathit, A.; et al. Comparisons of quality of life between patients underwent peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2020, 18, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, R. Quantitative research|Western Sydney University ResearchDirect. Nurs Stand 2015, 29, 44–48. Available online: https://researchdirect.westernsydney.edu.au/islandora/object/uws:34764 (accessed on 23 December 2020). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Berrocal, P.; Extremera, N.; Ramos, N. Validity and reliability of the Spanish modified version of the Traït Meta-Mood Scale. Psychol Rep. 2004, 94, 751–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angulo, R.; Albarracín, A.P. Validez y confiabilidad de la escala rasgo de metaconocimiento emocional (TMMS-24) en profesores universitarios. Rev Lebret 2018, 10, 61–72. [Google Scholar]

- Hays, R.D.; Kallich, J.D.; Mapes, D.L.; Coons, S.J.; WBC. Development of the kidney disease quality of life (KDQOL) instrument. Qual life Res. 1994, 3, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso, J.; Prieto, L.A.J. La versión española del SF-36 Health Survey (Cuestionario de Salud SF-36): un instrumento para la medida de los resultados clínicos [The Spanish version of the SF-36 Health Survey (the SF-36 health questionnaire): an instrument for measuring clinical resu. Med Clin. 1995, 104, 771–776. [Google Scholar]

- Hays, R.D.; Kallich, J.D.; Mapes, D.L.; Coons, S.J.; Naseem, A.; Carter, W. Kidney Disease Quality of Life Short Forma (KDQOL-SFtm), version 1.3 ed; A Manual for Use and Scoring; 1997; pp. 1–43. Available online: https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/papers/2006/P7994.

- Pabón-Varela, Y.; Paez-Hernandez, K.S.; Rodriguez-Daza, C.K.D. Eustralia Medina-Atencia ML-T y LVS-Q. Adult’s life quality with chronic kidney disease, a bibliographic view. Rev Duazary. 2015, 12, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, D.L.; Newman, D.A. Emotional Intelligence: An Integrative Meta-Analysis and Cascading Model. J Appl Psychol. 2010, 95, 54–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milivojevic, V.; Sinha, R.; Morgan, P.T.; Sofuoglu, M.; Helen, C. Fox. Effects of endogenous and exogenous progesterone on emotional intelligence in cocaine-dependent men and women who also abuse alcohol. Hum Psychopharmacol Clin Exp. 2014, 29, 589–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pardeller, S.; Frajo-apor, B.; Kemmler, G.; Hofer, A. Emotional Intelligence and cognitive abilities – associations and sex differences. Psychol Heal Med. 2018, 22, 1001–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCann, C.; Joseph, D.L.; Newman, D.A.R.R. Emotional intelligence is a second-stratum factor of intelligence: Evidence from hierarchical and bifactor models. Emotion 2014, 14, 358–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, A.H.; Kret, M.E.; Broekens, J. Gender differences in emotion perception and self-reported emotional intelligence: A test of the emotion sensitivity hypothesis. PLoS One 2018, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guil, R.; Gómez-Molinero, R.; Merchán-Clavellino, A.; Gil-Olarte, P. Lights and Shadows of Trait Emotional Intelligence: Its Mediating Role in the Relationship Between Negative Affect and State Anxiety in University Students. Front Psychol. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mcguire, C.L. Preparing Future Healthcare Professionals: The Relationship Between Resilience Emotional Intelligence, and Age. Digit Commons @ ACU Electron Theses Diss 2021, 372. Available online: https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/etd.

- Abbasabad Arabi, H.; Bastani, F.; Navab, E.H.H. Investigating quality of life and its relationship with emotional intelligence (EQ) in elderly with diabetes. Iran J Psychiatry Clin Psychol. 2015, 21, 215–224. [Google Scholar]

- Yarahmadi, F.; Ghasemi, F.; Forooghi, S. The effects of emotional intelligence training on anxiety in hemodialysis patients. J Nurs Midwifery Sci. 2015, 2, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Mokhatri-Hesari, P.; Montazeri, A. Health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients: Review of reviews from 2008 to 2018. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2020, 18, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muflih, S.; Alzoubi, K.H.; Al-Azzam, S.; Al-Husein, B. Depression symptoms and quality of life in patients receiving renal replacement therapy in Jordan: A cross-sectional study. Ann Med Surg 2021, 66, 102384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yapa, H.E.; Purtell, L.; Chambers, S.; Bonner, A. The Relationship Between Chronic Kidney Disease, Symptoms and Health-Related Quality of Life: A Systematic Review. J Ren Care. 2020, 46, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yalcin, B.M.; Karahan, T.F.; Ozcelik, M.; Igde, F.A. The effects of an emotional intelligence program on the quality of life and well-being of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Educ. 2008, 34, 1013–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudry, A.S.; Lelorain, S.; Mahieuxe, M.; Christophe, V. Impact of emotional competence on supportive care needs, anxiety and depression symptoms of cancer patients: a multiple mediation model. Support Care Cancer 2018, 26, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzo, R.P.; Kirsch, J.L.; Dulohery, M.M.; Abascal-Bolado, B. Emotional intelligence: A novel outcome associated with wellbeing and self-management in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016, 13, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Fernández, A.; Fernández-Berrocal, P.; Gutiérrez-Cobo, M.J. The Relationship Between Emotional Intelligence and Diabetes Management: A Systematic Review. Front Psychol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashby, D.; Borman, N.; Burton, J.; Corbett, R.; Davenport, A.; Farrington, K.; et al. Renal Association Clinical Practice Guideline on Haemodialysis. BMC Nephrol 2019, 20, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coelho, J.; Sampaio, F.; Teixeira, S.; Parola, V.; Sequeira, C.; Lleixà Fortuño, M.; et al. A relação de ajuda como intervenção de enfermagem: Uma scoping review. Rev Port Enferm Saúde Ment 2020, 23, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Male | Female | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (standard deviation) | Median (interquartile) | Mean (standard deviation) | Median (interquartile) | |

| Attention | 23.8 (7.466) | 24.00 [17–30] | 22.29 (8.319) | 21.00 [16.50-29.50] |

| Clarity | 28.80 (7.478) | 27.00 [24–36] | 26.59 (8.178) | 25.00 [23.00-31.50] |

| Repair | 27.29 (7.271) | 29.00 [22–33] | 27.35 (8.268) | 28.00 [20.50-34.00] |

| Physical function | Physical role | Pain | General health | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | p | Mean | p | Mean | p | Mean | p | |

|

Sex Male Female |

52.13 (28.56) 46.00 (30.12) |

0.120 |

42.97 (40.41) 44.38 (38.94) |

0.422 |

57.27 (31.94) 53.62 (31.89) |

0.261 |

37.58 (20.74) 36.83 (20.45) |

0.419 |

|

Age 25-45 46-65 >65 |

75.52 (17.15) 57.16 (27.14) 40.79 (27.99) |

<0.001 |

56.57 (38.94) 41.89 (38.66) 41.15 (40.51) |

0.305 |

62.76 (27.87) 61.28 (31.70) 52.01 (32.52) |

0.207 |

39.73 (17.27) 42.02 (20.29) 34.63 (21.15) |

0.166 |

|

Living situation Alone With family Nursing homes |

57.22 (32.86) 48.38 (28.53) 77.50 (10.60) |

0.199 |

38.88 (39.50) 43.64 (40.19) 75.00 (0.00) |

0,478 |

55.13 (33.06) 55.46 (31.69) 93.75 (8.83) |

0.242 |

38.88 (16.58) 36.73 (21.09) 57.50 (17.67) |

0.348 |

|

Level of education Primary Secondary University |

46.32 (29.09) 61.80 (27.07) 62.85 (25.79) |

0.027 |

39.85 (39.30) 53.00 (39.07) 64.28 (45.31) |

0.122 |

53.58 (31.50) 60.80 (30.10) 75.00 (39.55) |

0.160 |

36.42 (20.39) 39.60 (22.68) 42.85 (15.77) |

0.604 |

| Emotional wellbeing | Emotional Role | Social Function | Vitality | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | p | Mean | p | Mean | p | Mean | p | |

|

Sex Male Female |

64.51 (23.00) 61.38 (26.52) |

0.235 |

76.40 (37.42) 64.11 (45.33) |

0.045 |

66.03 (27.39) 61.22 (30.85) |

0.173 |

49.32 (24.27) 45.30 (27.22) |

0.187 |

|

Age 25-45 46-65 >65 |

68.42 (24.54) 65.18 (23.41) 61.43 (24.63) |

0.463 |

73.68 (39.40) 73.87 (38.59) 70.83 (42.27) |

0.916 |

71.44 (30.22) 65.20 (24.49) 62.28 (30.04) |

0.447 |

60.26 (22.20) 49.72 (23.83) 44.20 (25.93) |

0.038 |

|

Living situation Alone With family Nursing homes |

62.00 (23.61) 63.37 (24.58) 78.00 (2.82) |

0.679 |

79.62 (34.56) 70.97 (41.64) 66.66 (47.14) |

0.693 |

65.97 (26.36) 64.11 (29.14) 62.50 (35.35) |

0.964 |

44.44 (26.00) 48.13 (25.41) 65.00 (07.07) |

0.537 |

|

Level of education Primary Secondary University |

60.83 (24.17) 69.19 (24.11) 81.71 (15.45) |

0.036 |

69.26 (41.77) 81.33 (36.10) 80.95 (37.79) |

0.346 |

61.93 (28.23) 71.00 (29.69) 76.78 (28.34) |

0.182 |

46.41 (25.78) 49 .20 (23.34) 65.71 (20.70) |

0.143 |

| Coefficientsa.b | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non standarized coefficients | Standardized coefficients | t | Sig. | 95.0% CI for B | ||

| B | Std. Error | β | ||||

| Constant | 80.449 | 76.904 | 1.046 | .299 | -72.511 to 233.409 | |

| Age | .590 | .744 | .087 | .793 | .430 | -.890 to 2.070 |

| Level of education | 10.405 | 19.832 | .058 | .525 | .601 | -29.041 to 49.850 |

| Attention | -1.762 | 1.659 | -.128 | -1.062 | .291 | -5.062 to 1.538 |

| Clarity | -.253 | 2.057 | -.018 | -.123 | .903 | -4.345 to 3.839 |

| Repair | 3.805 | 2.200 | .270 | 1.730 | .087 | -.570 to 8.180 |

| Coefficientsa.b | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non standarized coefficients | Standardized coefficients | t | Sig. | 95.0% CI for B | ||

| B | Std. Error | β | ||||

| Constant | 242.504 | 96.294 | 2.518 | .016 | 48.309 to 436.699 | |

| Age | -1.666 | .866 | -.266 | -1.923 | .061 | -3.414 to .081 |

| Level of education | -6.354 | 27.897 | -.032 | -.228 | .821 | -62.614 to 49.905 |

| Attention | -3.730 | 1.816 | -.301 | -2.055 | .046 | -7.392 to -.069 |

| Clarity | -2.004 | 2.085 | -.159 | -.961 | .342 | -6.209 to 2.201 |

| Repair | 7.163 | 2.025 | .574 | 3.538 | <.001 | 3.080 to 11.247 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).