1. Introduction

A significant research effort is being put into making solar cells cheaper and easier to make [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. While this is a valuable area of research, making the cells cheaper is, on its own, not necessarily enough to enable photovoltaics (PV) to contribute significantly to a sustainable carbon mitigation strategy.

These PV approaches use materials which harvest the sun’s energy by using it to promote electrons across a “bandgap" energy step. The energy height of this step depends on the material system, and it has to be matched to the spread of photon energies in sunlight. Too high a value and excessive amounts of the red end of the rainbow is missed, because its photons do not have enough energy to promote the electrons. Too low a value and a large fraction of the energy in the blue end of the rainbow is lost, because the excess energy given to the promoted electrons is lost as heat in the device as they relax back down to the band edges. Even with the bandgap energy perfectly chosen, and even if all the practical engineering issues can be completely solved, this trade-off means that today’s fixed single-junction PV technologies offer a power conversion efficiency (PCE) which is theoretically capped at ~33%, the so-called Shockley-Queisser (S-Q) limit [

7,

8].

Here we analyse the practical consequences of this, in light of the fact that in the urbanised societies which consume the most part of the world’s energy, space is a highly valued resource; this is a topic that has been considered by others, but no numerical analysis of the situation has been performed [

9]. We first look at the option of mounting solar panels on the roofs of houses, and calculate, in an idealised model, the limits to the amount of energy that could be generated using the technology with the best commercially available PCE panels.

For definiteness we use the term Contribution to denote the fraction that PV could supply of the current total UK energy budget, and take 15% as the value at which PV could be said to contribute “significantly” to a sustainable energy future. We also define the term mPCE to denote the minimum PCE required of a PV technology to generate a given Contribution. This is all done under the most optimistic assumptions of how well a roof-mounted PV system could be implemented in practice.

Finally, we consider the alternative option, which is both much simpler to model, yet politically much more challenging to implement: that of large-scale solar farms. Again, for discussion purposes, we make similarly generous and optimistic assumptions. We present estimates of the land areas that would be required to generate a significant Contribution.

2. Methods

2.1. Description of the Model

Our calculations here are directly impacted by three angles that relate to how solar panels are installed. Namely the latitude,

; the angle to the local horizontal at which the panels are mounted,

; and the azimuthal angle of the panels to the meridian,

. The way the effective PCE is affected by these is derived geometrically in

Section 2.4 to find an overall obliquity factor suitably averaged through the day/year, and, for roof-mounted arrays, through the random distribution in

.

For all calculations involving roof-mounted PV, the insolation data and statistics on roof area and energy consumption that have been used are those for the UK or London. The key aspects of the city’s built environment and energy utilisation have been widely and recently surveyed, and publicly reported. Also, London typifies the modern mega-city, with high population density. Its temperate climate is fairly typical for the developed world [

10], and its latitude is similarly typical of large population centres, resulting in the key obliquity factors that emerge from the analysis outlined above also being representative of the environments where much of the world’s energy is being consumed.

Our calculations are idealised, and are intended for discussion purposes. To this end, at all points where assumptions must be made, we do so in a way that would generate an underestimate of the actual PCE required, even if the degree of underestimation this introduces may be quite significant.

We assume that roof coverage is as complete as practically possible (see

Section 2.3.2) and that all the panels are mounted on roofs that are optimally inclined to the horizontal (

Section 2.4.1Error! Reference source not found.).

As is discussed more thoroughly in

Section 2.3.2, we have had to assume that the statistics for flat dwellers should be processed by assuming that all apartment blocks are only 2 storeys high. In reality of course, many are very much taller and the share of the roof area available to each flat dweller is much lower as a result, so this assumption means that our calculations are likely to considerably overestimate the PV generation capacity in cities.

We are also assuming that none of the generated energy is lost in either storage or transmission schemes (see

Section 2.2).

These issues are commercially and politically sensitive to the point where accessing reliable, unbiased data for analytical studies is problematic. However, by setting our definition of “significance” to only 15%, i.e. rather less than the 60% used by the non-transport sector, we aim to sidestep these complications by making our conclusions largely independent of what might happen to the transport sector in future.

2.2. Factors Surrounding the “Perfect Storage” Assumption

In all our calculations we assume that no energy generated by a PV system goes to waste. For this idealisation to be the case, it must be possible to store any excess energy, with no losses, for later use when there is a generation deficit. Using the 15% Contribution figure for discussion makes this a more practical proposition if one assumes that the overall energy generating system contains flexible elements whose generating capacity can be switched in and out as the generating capacity of the PV component fluctuates. However, the issue would become progressively more challenging if PV were to aim for higher Contribution levels.

This issue is quantified in the

Supplementary Material, where we show that a PV system able to generate a 15%

Contribution annually may be limited over winter to a

Contribution as low as ~3%, but >30% at times over summer. This means other sources would need to provide up to 97% in winter but only ~70% in summer.

At higher assumed

Contribution values, storage issues become relevant, because the installed capacity required could, in principle, generate more energy in summer than the UK could consume. The excess could be exported, or be stored. If one assumes the latter is done with today’s best battery technology, lithium-ion, the recovery efficiency is ~80% [

11,

12], and there is a loss, due to self-discharging, of ~3% per month [

13]. Taking these effects into account, storing enough energy for six months, to cope with seasonal variations, would increase the corresponding

mPCEs by a factor of 1.5. This is a combination of a 1.25 factor due to the finite energy efficiency, and a further factor of 1.2 to account for six months at 3% per month self-discharge.

2.3. Data Collection

Wherever possible, the data used in the calculations have been sourced from official documents such as government reports and statistical tables, and uncertainties have been taken from standard deviations or estimated from the data available. To be able to perform the analysis, we require data for the insolation that reaches the surface of the Earth, the energy consumption of the UK (as a whole and for individual households), and the available rooftop area that can be used to mount solar panels.

2.3.1. Energy – Insolation and Consumption

Insolation data have been sourced from NASA's Projection Of Worldwide Energy Resources (POWER) [

14], which provides insolation data at a given location to a 0.5° precision of both latitude and longitude. The data are a daily average for each calendar month of all sky insolation on a horizontal surface using solar climatological datasets which span from July 1983 – June 2005 [

14].

Data for total annual energy consumption in the UK is taken from the Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy's (DBEIS's) Energy Consumption in the UK (ECUK) 2018, using 2017 data [

15]. For calculations that separate homes by type of dwelling, we have used the average annual household consumption from ECUK [

15], and scaled it using electricity data taken from the Household Electricity Survey [

16].

2.3.2. Available Roof Area

The available roof area is taken from the Energy Saving Trust (EST) [

17], which provides values for a selection of different types of home. The values given by the EST use dwelling footprints from a report by the BRE Group on behalf of the Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions [

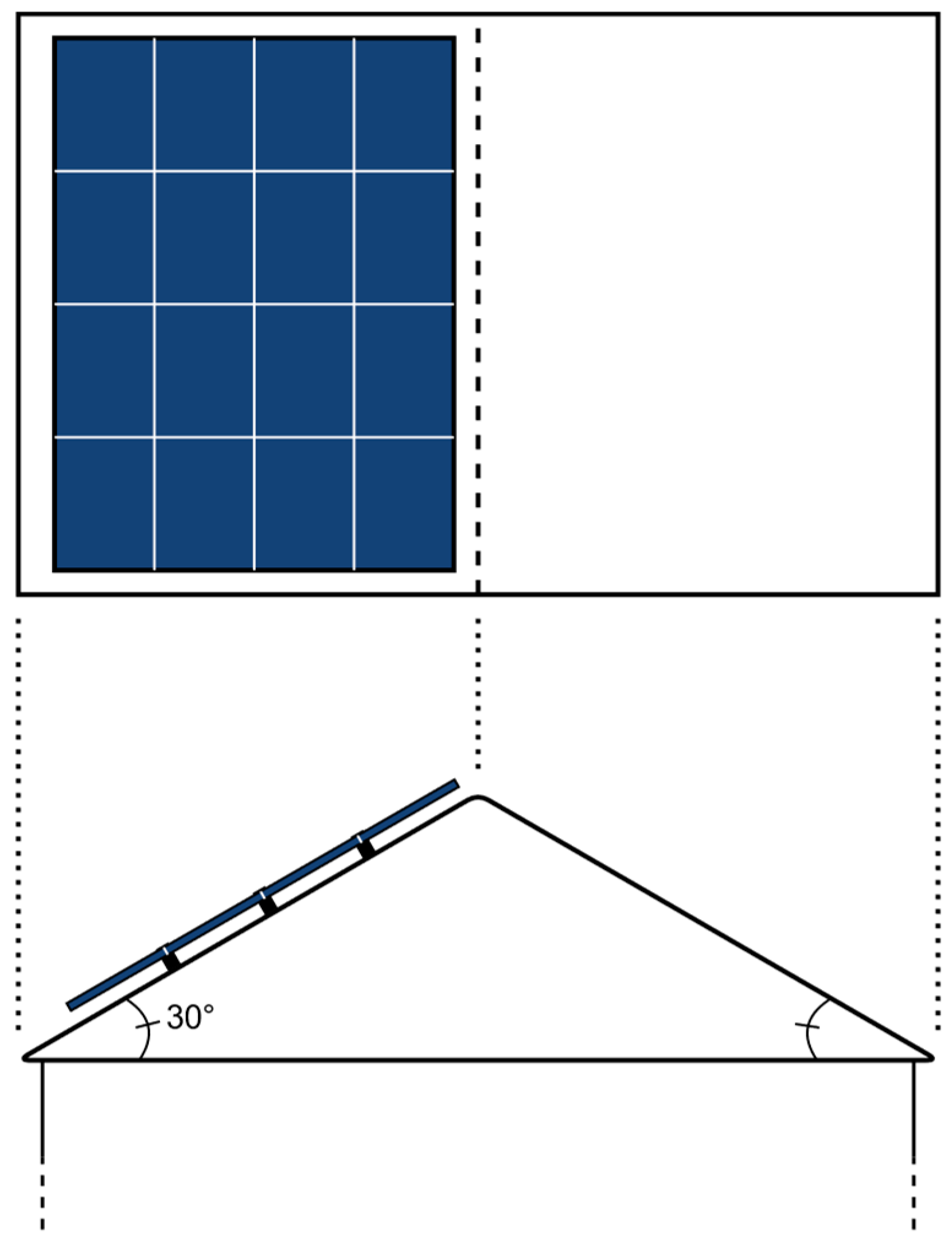

18], then assume each has a pitched roof with a slope of 30°, meeting in the middle; they have assumed that solar panels can be mounted on only one half of the roof, with a further 20% of this unsuitable. This is shown in

Figure 1. We have adjusted the resulting areas quoted by the EST by a factor of

to find the horizontal cross-sectional area (HCSA) – the cross-sectional area as viewed from directly above. This can then be used in conjunction with the insolation data from NASA POWER, which are for a horizontal surface [

14].

The roof area provided by the EST for a flat was 28m

2 (giving a HCSA of 24.2m

2), and was for a “top floor flat” [

17]. We have taken half that value, as the term “top floor” implies the existence of at least one flat below this one, and the available roof area should be split equally between them. As such, we have estimated an increased uncertainty in the HCSA for the flat, relative to the other types of home. In the absence of any further information, for discussion purposes, we must assume that only one flat exists below the top floor, but this means that all the estimates of roof areas available to flat dwellers are likely to be significant overestimates, and the calculations will be strongly biased in favour of lower

mPCE estimates.

Flats make up a large fraction of all households in large cities (~44% in London in 2011 [

19]), and any overestimate in the roof area estimates for a flat will translate to an overestimate by a factor of around half as much in the roof area values for an average home. With blocks of flats often standing at more than three storeys, and tower blocks having storeys in the double figures, the roof area per flat is probably very significantly less than the calculation assumes, but this would be offset by the fact that the calculation ignores the roof areas that might be available on commercial properties (see Section

Error! Reference source not found.).

2.3.3. Solar Farms and Today’s PCEs

Further data that we researched include the locations of existing solar farms in the UK. We considered the five largest by declared net capacity [

20]. The coordinates for each were taken from Google Maps [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25] using the addresses provided by Ofgem [

20]. We input these coordinates into NASA POWER [

14] and used the location of that which received the highest annual insolation for our calculations of a theoretical solar farm.

Finally, in order to estimate the capability of the solar technology that is currently available, we used six independent web pages that purport to list the most efficient solar panels on the market. The highest reported PCEs ranged from 21.5–23.8% [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. In this investigation we take the highest value of 23.8%, as this provides the most optimistic results for today’s technology, and therefore challenges our hypothesis the most strongly. This value of 23.8% is hereafter referred to as PCE

NOW.

2.4. Geometrical Factors

2.4.1. The Obliquity Factor from Solar Panel Orientation

The theoretically ideal orientation of a solar panel – assuming its orientation is fixed – is to mount it at an angle to the horizontal that is equal to the latitude of its location, and to have it aligned meridionally, facing the equator. This would mean the incident solar rays, on average over the course of the year, are normally incident on the panel, and thus the cross-sectional area of the panel is maximised. However, this is not always practical. Especially for roof-mounted solar panels, the angle to the horizontal, and indeed the azimuthal angle to the meridian, are generally fixed by the slope of the roof and the orientation of the house, respectively.

For a solar panel at a location with latitude

, the average angle to the horizontal of incoming solar rays over the course of the year is (

). On top of this, the cross-sectional area of the solar panel that collects sunlight also depends upon the angle of the panels to the horizontal, θ, and the azimuthal angle to the meridian,

.

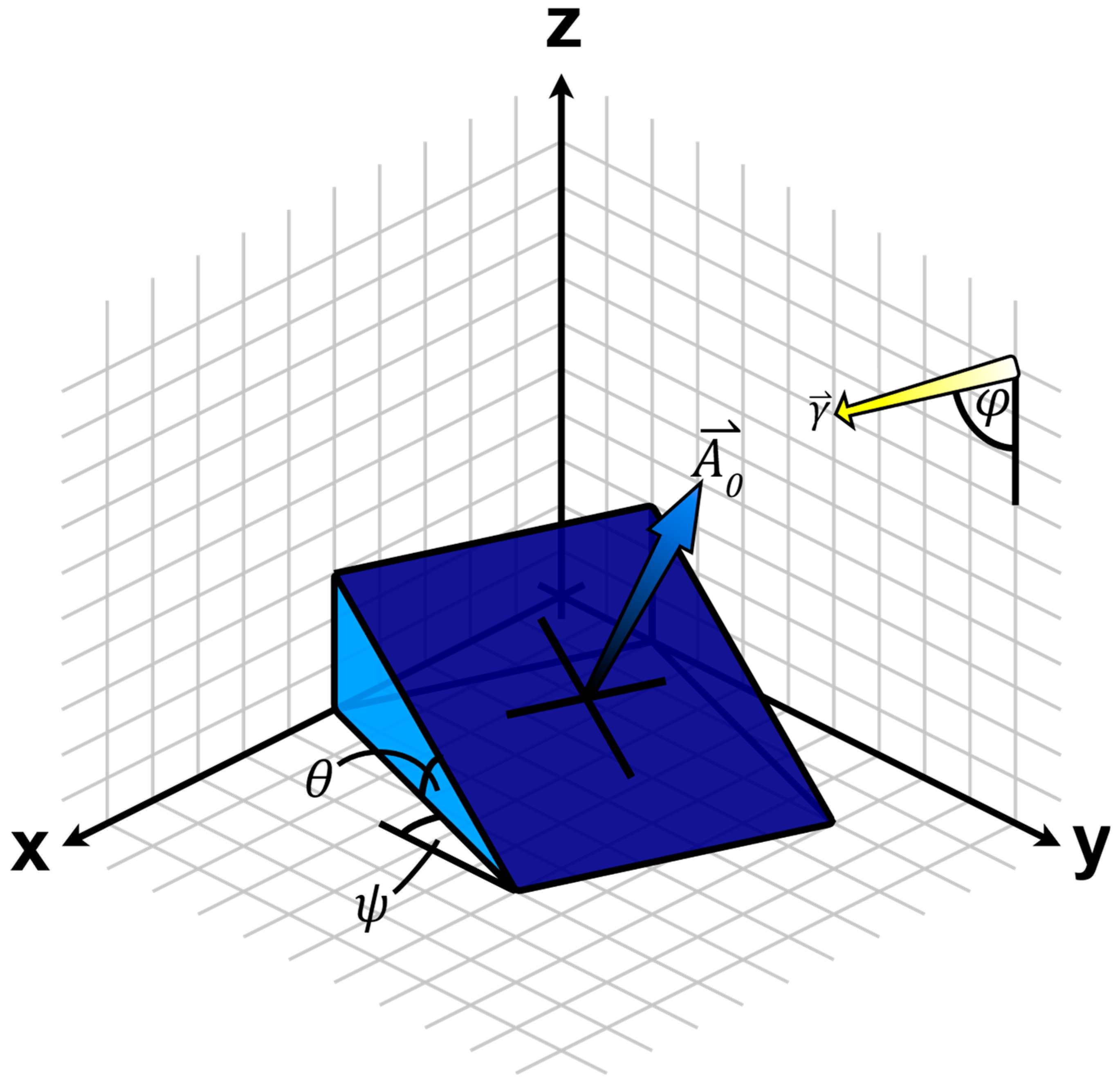

Figure 2 illustrates this. By taking the inner product of the vectors labelled

and

in

Figure 2 – normal to the surface of the panel and average trajectory of incident sunlight, respectively – the cross-sectional area seen by incident sunlight is found to be multiplied by an obliquity factor,

, given by,

In this study, we assume that the orientation of houses in the UK are randomly distributed, and so we average this over the appropriate range of azimuthal angles, i.e.

. The obliquity factor that emerges is then given by,

where the

in the denominator is a normalisation factor such that

, meaning the cross-sectional area of the panels when lying flat is unchanged by the obliquity factor. Taking the latitude of London to be

51.5072° [

32], the obliquity factor

– and therefore the insolation received – is maximised to a value of 1.281 for a roof incline of 39°.

If it is possible to align the azimuthal angle directly with the meridian – as would be the case for a free-standing array of solar panels in a solar farm – the normalised obliquity factor relative to a flat panel is given instead by,

which peaks when

, giving a value of

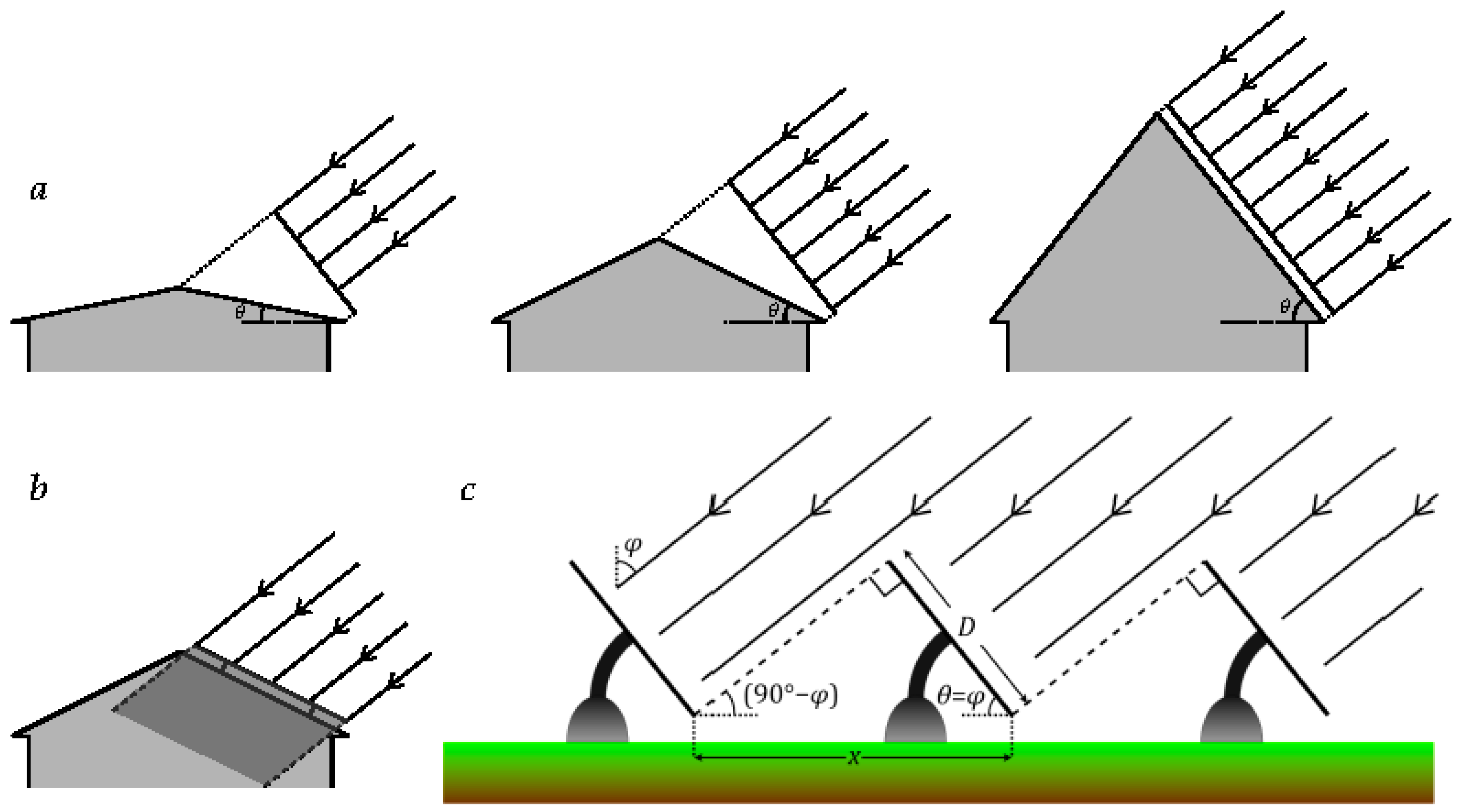

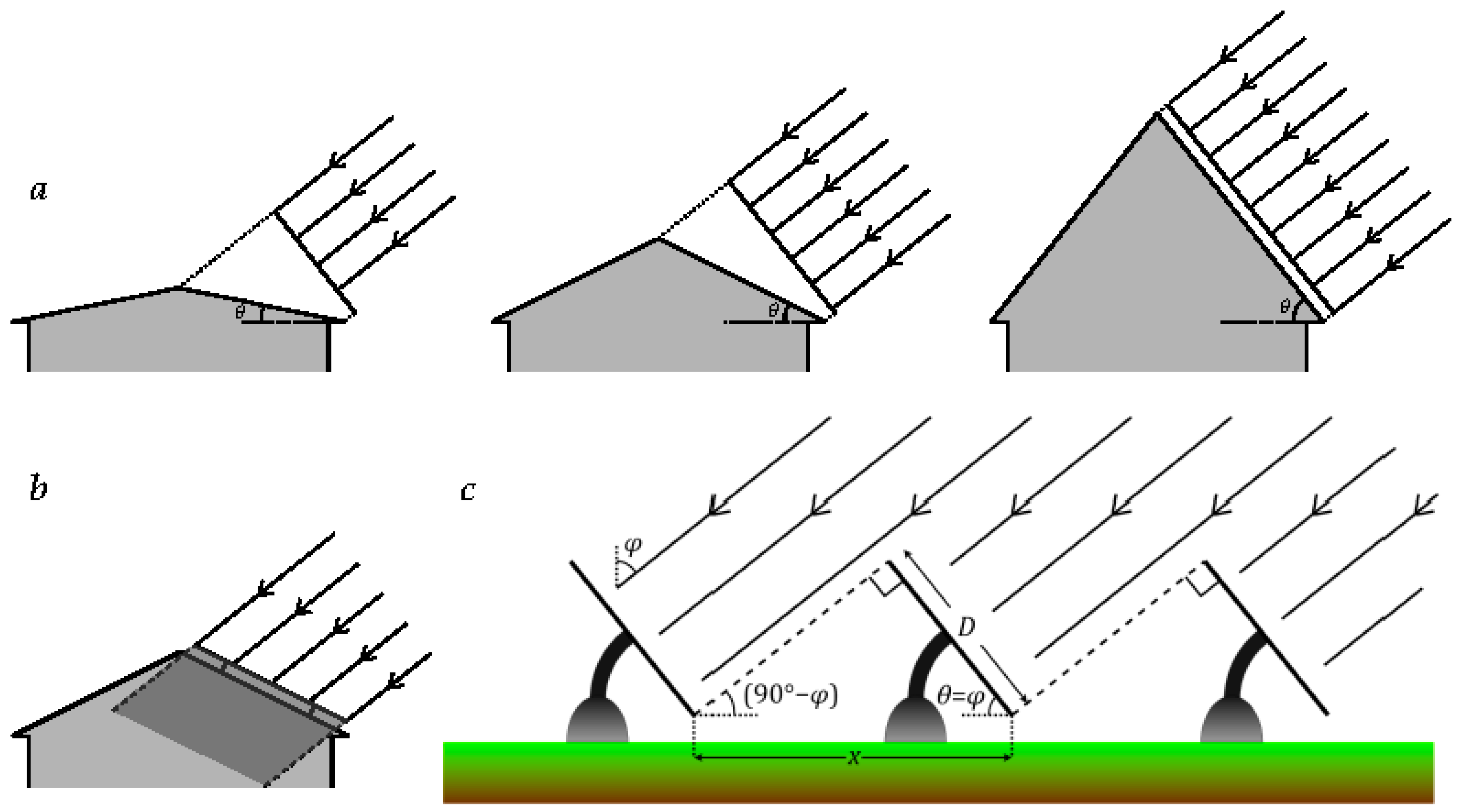

2.4.2. Separation of Rows of Solar Panels

Figure 3 illustrates the effect of tilting solar panels in rooftop and free-standing solar arrays, highlighting also the effect on the space needed between rows of solar panels in a farm. In large-scale solar arrays that have multiple rows of solar panels, tilting the panels at a steeper angle means they must be spaced further apart in order to minimise the shadows cast by one row of panels on the next (

Figure 3c). This is not a problem for roof-mounted arrays, which generally comprise just one row, meaning shadows cast by panels are irrelevant (

Figure 3b).

For a solar farm, the value of the panel spacing is labelled

in

Figure 3c. When the panels are laid flat (i.e. at

) this is simply equal to the length of the panels,

. However, setting

in order to minimise the amount of material needed (see

Supplementary Material), the separation,

, is changed by a factor,

, given by,

as illustrated in

Figure 3c. This shows that the factor by which the necessary separation of successive rows increases,

, is the same as the factor by which received insolation increases,

. This result means that tilting the panels in a solar farm does not affect the amount of land area needed to generate a given amount of energy. The

spatial efficiency – a measure of the amount of flat land area required to generate a given amount of power, for a fixed PCE and fixed insolation on a horizontal surface of an array of consecutive rows of solar panels – is independent of the angle at which the solar panels are tilted to the horizontal.

Note that due to the integral nature of the number of rows of solar panels in a solar farm, this result is not always exact, however the variation for large numbers of rows are small: variations are <1% at all latitudes <69° for ≥250 rows. With 99% of the world's population living within 60° of the equator [

33], and the areas involved in these calculations necessitating many rows, this formula is considered to be exact in this paper. More detail on the exact variations is given in the

Supplementary Material.

2.5. Weighted Mean Energy Consumption Per Unit Area by House Type

Despite the 28m

2 given by the EST [

17], the roof area that corresponds to a single flat is likely to be smaller even than the 14m

2 used here, as blocks of flats are often several stories high, especially in crowded cities. The 2011 census showed that almost half of all households in London were flats at that time [

19], meaning the data for flats are especially important in reaching the value for the average home.

Indeed, we have calculated values for an average home in the UK using a weighted mean consumption per unit HCSA, as shown in

| House Type |

No. in London (2011) [19] |

Upscaled Energy Consumption (kWh/m2) |

Weighted Fractional Consumption (kWh/m2/yr) |

| Terrace |

756,988 |

2730 |

740 |

| Semi-detached |

617,647 |

3400 |

750 |

| Detached |

205,422 |

2490 |

180 |

| Flat |

1,219,534 |

3570 |

1560 |

| —Total— |

2,799,591 |

— |

3229±1004 |

Table 1 Calculating the weighted mean total annual energy consumption for homes in London. The energy consumption of each home type has been upscaled to account for all sectors, rather than just domestic (the total value is not upscaled, as the weighted fractional value is simply the sum of the constituent parts).

Table 1. The energy consumptions found for different types of home using the HES [16] and the

ECUK [15] give values for domestic energy use. The domestic sector makes up ~30% of the total

energy consumption in the UK [15]; in order to account for the total energy needs of the UK, these

values are upscaled using the ratio of the UK’s total annual energy consumption in all sectors (141ktoe

[15]) to that in the domestic sector (40ktoe [15]). The upscaled value is that which is included in

| House Type |

No. in London (2011) [19] |

Upscaled Energy Consumption (kWh/m2) |

Weighted Fractional Consumption (kWh/m2/yr) |

| Terrace |

756,988 |

2730 |

740 |

| Semi-detached |

617,647 |

3400 |

750 |

| Detached |

205,422 |

2490 |

180 |

| Flat |

1,219,534 |

3570 |

1560 |

| —Total— |

2,799,591 |

— |

3229±1004 |

We then divide the upscaled consumption values by the HCSA for each type of dwelling, and weight them using the number of households of each type, as given by the Census Information Scheme for the 2011 census [

19]. The resulting values are then summed to find a weighted mean annual energy consumption per unit HCSA.

The same method is used to calculate a weighted mean HCSA for the calculation in Section Error! Reference source not found. of the amount of solar panel material that would be needed to install panels on every domestic rooftop in the UK.

3. Results & Discussion

3.1. Contribution from Today’s Best Roof-Mounted Solar Panels

We consider first a scenario with solar panels covering the roof of every home in the country in order to achieve grid-level generation capacity that produces a significant

Contribution. We have not considered commercial/industrial rooftops, as these buildings are generally not only more densely built (using a smaller area per occupant), but also generally have more storeys still, and their roofs are often used to site plant. These issues all result in a small available roof area per occupant. For rooftop calculations, we use the obliquity factor,

, from Equation 2, to multiply the insolation data from NASA POWER [

14], and take

= 51.5° using [

32].

We are supposing that all domestic roofs are covered as fully as possible with solar panels of PCE equal to PCE

NOW. We calculate the power that could be generated by the different classes of dwelling, which gives a

Contribution scaled with the average consumption of each type of home. We then calculate the

Contribution for an average home by taking a weighted mean on the annual consumption per unit area (as detailed in

Section 2.5).

The results by types of home, and for the average home, are shown in

| House Type |

Contribution available from Panels with 23.8% PCE |

| Terrace |

11±2 % |

| Semi-detached |

9±2 % |

| Detached |

12±2 % |

| Bungalow |

14±3 % |

| Flat |

9±4 % |

| Average Home |

9±3 % |

Table 2, where we have assumed the roof pitch to be the optimal 39° (see Section 2.4.10) for the latitude of London.

These Contributions show that – in this idealisation – the average home could generate a Contribution of up to ~9%. This is likely to be a considerable overestimate due to all the assumptions that we have made favouring high Contributions. We estimate that on average, the effective available roof area per flat might be another factor of two (i.e. corresponding to a mean block height of 4 floors) lower than the 14m2 used here; this would mean a 50% change in the values for the average home. Combining this with the assumptions of perfect storage and optimal roof incline, we believe the Contribution for PCENOW is more likely to be ⪅5%.

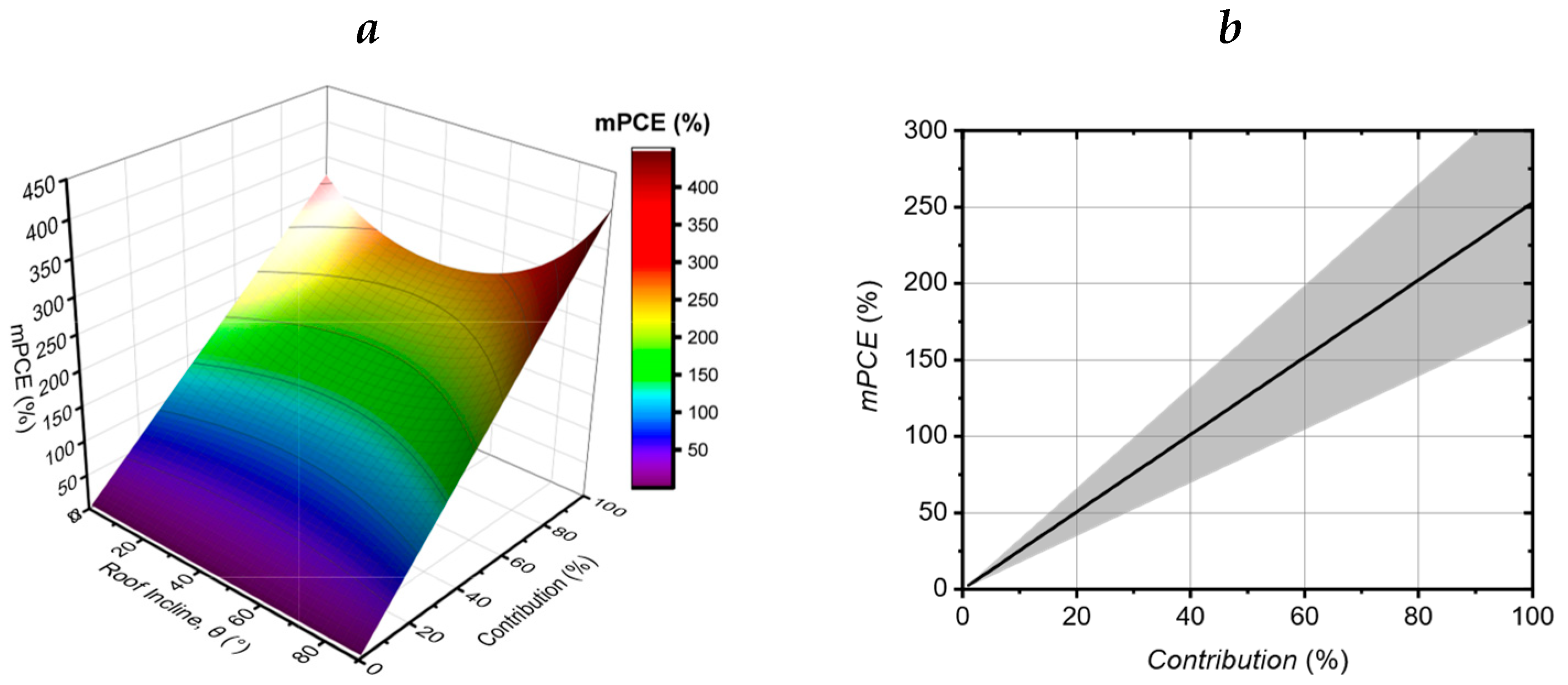

3.1. mPCEs for roof-mounted PV to provide a 15%Contribution

We have repeated the calculations above, first constraining the

Contribution and then determining the corresponding

mPCEs that would be required to achieve them. The results for the average home are shown in

Figure 4a, as a function of both roof pitch and

Contribution.

Figure 4b shows a cross-section of this at a fixed roof pitch of 39°, the angle corresponding to the lowest

mPCEs. The shaded region in

Figure 4b shows the uncertainty.

In this case we can see that to generate a Contribution of 15% would require a PCE of ~37%, which is in excess of the S-Q limit of ~33%. If the PCE is equated to the S-Q limit, a Contribution of ~13% might be generated. However, these values again correspond to the highly optimistic idealised case, with the additional assumption here that all roofs are optimally pitched.

In order to gauge the feasibility of mounting solar panels on all domestic roofs in the UK, we should also consider the quantity/area of solar panel material that would be needed. The mean available roof area weighted by number of dwelling types is found to be ~15m

2; this is the HCSA, while the area of material actually depends on the absolute area of the inclined roof. Assuming a pitch of 39°, this is ~19.5m

2. Taking the number of households in the UK to be 28 million (according to a recent government report [

15]), this gives a total panel area of ~550km

2.

Clearly this would be a major undertaking. One would hope there would be very significant economies of scale, and because of this, present day comparisons based on cost-per-watt estimates for PV technologies must be treated with extreme caution. There is a risk that premature costing exercises could unwittingly rule out research into high-PCE approaches that in fact have the better long-term likelihood of producing a significant contribution to carbon-mitigation.

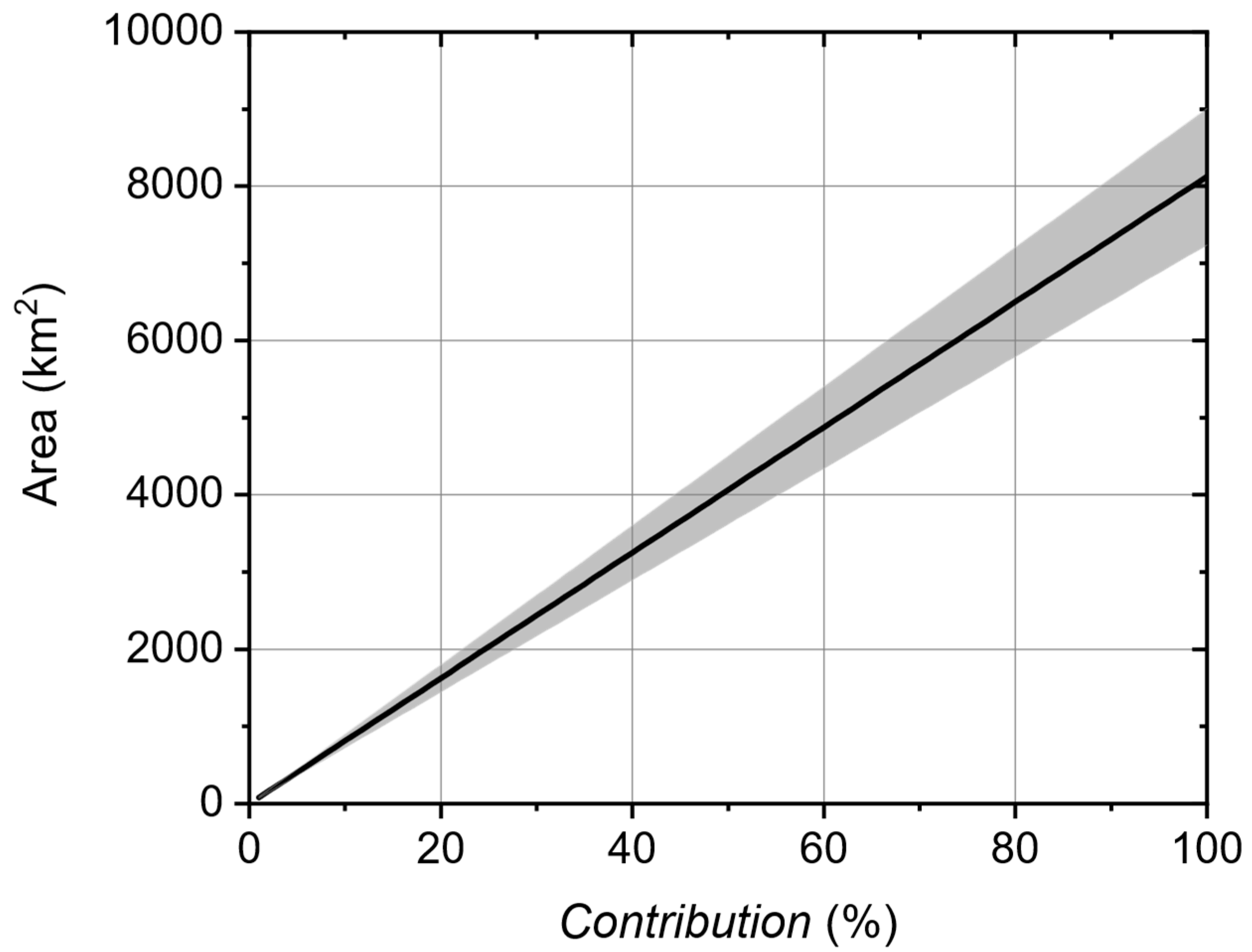

3.3. The Area Needed for a Single Solar Farm in the UK

An alternative to roof-mounted solar arrays is to construct a number of large-scale solar farms. Here we calculate the land area that would have to be dedicated to a solar farm as a function of

Contribution, using solar panels of PCE

NOW. In this calculation we suppose that the panels, if tilted, are built facing meridionally south (

); we therefore use the obliquity factor

from Equation 3 in

Section 2.4.1. The results are shown in

Figure 5, where the shaded area represents an estimate of uncertainty, the main source of which in this case is the energy consumption data.

The calculation is straightforward, with the result being that over 1200km

2 of new land area would have to be dedicated to solar panels to produce enough energy to fulfil 15% of the energy needs of the UK. As a percentage of the nation’s area it is small, yet it corresponds to a land area that is comparable to the size of Greater London [

34], and would most likely be impossible to implement either politically or logistically. That said, in this scenario, even small improvements in PCE correspond to large savings in land area. For example, if the PCE were raised from PCE

NOW by one percentage point (23.8 to 24.8%), the area needed for a 15%

Contribution would decrease by ~50km

2, roughly the size of a large county town in the UK.

These values of land area are unaffected by the tilt of the solar panels according to the constant nature of the

spatial efficiency, a concept discussed in

Section 2.4.2. If the panels were laid flat, the area of solar panel material would be the same as the land area (i.e. ~1200km

2). However, if they were tilted at 52° to the south, this would be reduced by a factor of ~38%, meaning ~750km

2 of panel material would be needed for the 1200km

2 farm that would be capable of generating a 15%

Contribution.

This is ~250km

2 more material than would be needed to cover all the UK’s domestic roofs; this difference arises from two factors. First, this calculation assumes that the farm is in fact large enough to generate a 15%

Contribution, whereas there is only enough roof area to generate a ~9%

Contribution using the same PCE. Secondly, the obliquity factors are different for the two cases because the orientation of the panels,

, can be optimised in the farm, but is dictated by the spread of house orientation for the rooftop case. There are further details of this calculation in the

Supplementary Material.

4. Conclusions

Here we have attempted to calculate the fraction of the UK’s energy consumption that could be generated by the best PV technology currently available, factoring in the key consideration of where the panels could realistically be deployed.

This calculation is, necessarily, highly idealised, and it certainly overestimates the possible contribution that today’s PV technology could make. We have found that the most efficient solar panels available today, if installed on every domestic roof in the UK, would be able to produce up to ~9% of the UK's energy. Due to the assumptions made in this analysis, particularly the assumption regarding the roof area available to every flat dweller, we believe that a more realistic figure is less than ~5%.

Using the same generous assumptions, we find that the PCE would need reach values of at least ~37% for roof-mounted solar PV to contribute 15% of the UK’s energy needs. The same caveats over the available roof area in apartment buildings apply as above, and the real PCEs needed would likely be rather larger still. This already exceeds the Shockley-Queisser theoretical limit of 33%, and will only become possible with so-called “third generation” PV technologies. These are currently at the research stage, and typically employ e.g. multi-bandgap and other quantum engineering approaches to circumvent the shortcomings of the single junction devices that were considered in calculating this limit [

5,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45].

We have determined that approximately 1200km2, an area comparable to the size of Greater London, would be needed for a solar farm to generate 15% of the UK's energy using the most efficient solar panels currently available.

Our broad conclusion is that, independent of the commonly used “dollar-per-watt” economic metric, if solar PV is to become a significant part of any carbon mitigation strategy, then research and development programmes must target a raw increase in PCEs. Not only are values required that are beyond those currently available, but also well beyond the Shockley-Queisser limit of single bandgap approaches.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.M.H.; methodology, K.M.H.; software, K.M.H.; validation, K.M.H. and C.C.P.; formal analysis, K.M.H.; investigation, K.M.H.; resources, K.M.H.; data curation, K.M.H.; writing—original draft preparation, K.M.H.; writing—review and editing, K.M.H. and C.C.P.; visualization, K.M.H.; supervision, C.C.P.; project administration, K.M.H. and C.C.P.; funding acquisition, C.C.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Kojima, K. Teshima, Y. Shirai, T. Miyasaka, Organometal Halide Perovskites as Visible-Light Sensitizers for Photovoltaic Cells, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131 (2009) 6050–6051. [CrossRef]

- Z. Cheng, J. Lin, Layered organic-inorganic hybrid perovskites: structure, optical properties, film preparation, patterning and templating engineering, CrystEngComm. 12 (2010) 2646–2662. [CrossRef]

- Q. Jiang, Z. Chu, P. Wang, X. Yang, H. Liu, Y. Wang, Z. Yin, J. Wu, X. Zhang, J. You, Planar-Structure Perovskite Solar Cells with Efficiency beyond 21%, Adv. Mater. 29 (2017) 1703852. [CrossRef]

- H.-S. Kim, C.-R. Lee, J.-H. Im, K.-B. Lee, T. Moehl, A. Marchioro, S.-J. Moon, R. Humphry-Baker, J.-H. Yum, J.E. Moser, M. Grätzel, N.-G. Park, Lead Iodide Perovskite Sensitized All-Solid-State Submicron Thin Film Mesoscopic Solar Cell with Efficiency Exceeding 9%, Sci. Rep. 2 (2012) 591. https://www.nature.com/articles/srep00591#supplementaryinformation. [CrossRef]

- Oxford PV, Oxford PV sets new solar cell world record, Oxford PV. (2023). https://www.oxfordpv.com/news/oxford-pv-sets-new-solar-cell-world-record (accessed January 12, 2024).

- J.M. Ball, A. Petrozza, Defects in perovskite-halides and their effects in solar cells, Nat. Energy. 1 (2016) 16149. [CrossRef]

- W. Shockley, H.J. Queisser, Detailed Balance Limit of Efficiency of p-n Junction Solar Cells, J. Appl. Phys. 32 (1961) 510–519. [CrossRef]

- S. Rühle, Tabulated values of the Shockley-Queisser limit for single junction solar cells, Sol. Energy. 130 (2016) 139–147. [CrossRef]

- M.A. Green, S.P. Bremner, Energy conversion approaches and materials for high-efficiency photovoltaics., Nat. Mater. 16 (2016) 23–34. [CrossRef]

- Solargis, Global Solar Atlas 2.0, (2023). https://globalsolaratlas.info/map (accessed January 12, 2024).

- Pei Zhang, Changqing Du, Fuwu Yan, Jianqiang Kang, Influence of practical complications on energy efficiency of the vehicle’s lithium-ion batteries, in: 2011 Int. Conf. Electr. Inf. Control Eng., 2011: pp. 2278–2281.

- A. Eftekhari, Energy efficiency: a critically important but neglected factor in battery research, Sustain. Energy Fuels. 1 (2017) 2053–2060. [CrossRef]

- M. Vetter, S. Lux, Rechargeable Batteries with Special Reference to Lithium-Ion Batteries, in: Storing Energy, Elsevier, Oxford, 2016: pp. 205–225. [CrossRef]

- NASA Langley Research Center, POWER Data Access Viewer, (2018). https://power.larc.nasa.gov/data-access-viewer/ (accessed January 12, 2024).

- Department for Business Energy & Industrial Strategy, Energy Consumption in the UK (ECUK) 2018 Data Tables, (2018). https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20190509005513/https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/energy-consumption-in-the-uk (accessed January 12, 2024).

- J.-P. Zimmerman, M. Evans, J. Griggs, N. King, L. Harding, P. Roberts, C. Evans, Household Electricity Survey A study of domestic electrical product usage, 2012. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/208097/10043_R66141HouseholdElectricitySurveyFinalReportissue4.pdf.

- Energy Saving Trust, Solar Energy Calculator Sizing Guide, (2015). https://energysavingtrust.org.uk/tool/solar-energy-calculator/ (accessed January 12, 2024).

- P.J. Iles, Standard Dwellings for Energy Modelling, 1999.

- GLA Intelligence Census Information Scheme, 2011 Census Housing Characteristics, (2013). https://data.london.gov.uk/download/2011-census-housing/377bcc89-fab4-4f88-a69f-10a2570cbde5/2011-census-housing-characteristics.pdf.

- Ofgem, Ofgem Renewables and CHP Register, (2007). https://www.renewablesandchp.ofgem.gov.uk/Public/ReportManager.aspx?ReportVisibility=1&ReportCategory=0 (accessed January 12, 2024).

- Google, Google Maps – Shotwick Solar Park, (2024). https://www.google.com/maps/place/Shotwick+Solar+Park/@53.2385404,-3.0204782,17z/data=!3m1!4b1!4m5!3m4!1s0x487adbb6a8432c33:0x3faa669894904fac!8m2!3d53.2385404!4d-3.0182895 (accessed January 12, 2024).

- Google, Google Maps – West Raynham Solar Farm, (2024). https://www.google.com/maps/place/West+Raynham+Solar+Farm/@52.7874045,0.7399422,17z/data=!3m1!4b1!4m5!3m4!1s0x47d783aa7ac52a71:0xf9c9cb1d996c041!8m2!3d52.7874045!4d0.7421309 (accessed January 12, 2024).

- Google, Google Maps – Eveley Farm, (2024). https://www.google.com/maps/place/Eveley+Farm/@51.093952,-0.8895097,17z/data=!3m1!4b1!4m5!3m4!1s0x487430d56909b8a7:0xbf25e5fff47d9c0d!8m2!3d51.093952!4d-0.887321 (accessed January 12, 2024).

- Google, Google Maps – National Collections Centre, (2024). https://www.google.com/maps/place/National+Collections+Centre/@51.5107303,-1.8148946,17z/data=!3m1!4b1!4m5!3m4!1s0x487144a87ad0f6b9:0x30375e0b110613b9!8m2!3d51.510727!4d-1.8127059 (accessed January 12, 2024).

- Google, Google Maps – MOD Lyneham, (2024). https://www.google.com/maps/place/MOD+Lyneham/@51.5055658,-1.9714883,17z/data=!3m1!4b1!4m5!3m4!1s0x487168869f38ccb5:0xab41dd8fb3e8c7c3!8m2!3d51.5055658!4d-1.9692996 (accessed January 12, 2024).

- C. Clissit, Most Efficient Solar Panels 2020, Eco Expert. (2020). https://www.theecoexperts.co.uk/solar-panels/most-efficient (accessed March 23, 2020).

- V. Aggarwal, What are the most efficient solar panels on the market? Solar panel cell efficiency explained, Energy Sage. (2020). https://news.energysage.com/what-are-the-most-efficient-solar-panels-on-the-market/ (accessed March 23, 2020).

- S. Chakrabarti, Top 10 Solar Panels in the UK in 2019, Sol. Feed. (2019). https://solarfeeds.com/top-solar-panels-in-the-uk/ (accessed March 23, 2020).

- How Efficient Are Solar Panels?, Househ. Quotes. (2019). https://householdquotes.co.uk/how-efficient-are-solar-panels/ (accessed March 23, 2020).

- J. Svarc, Most Efficient Solar Panels, Clean Energy Rev. (2019). https://www.cleanenergyreviews.info/blog/most-efficient-solar-panels (accessed March 23, 2020).

- What is the Most Efficient Solar Panel, Joju Sol. (2019). https://www.jojusolar.co.uk/2017/06/06/high-efficiency-solar-panel/ (accessed March 23, 2020).

- Wikimedia Tool Labs, GeoHack – London, (2024). https://geohack.toolforge.org/geohack.php?pagename=London%5C¶ms=51_30_26_N_0_7_39_W_region:GB_type:city(8825000) (accessed January 12, 2024).

- M. Kummu, O. Varis, The world by latitudes: A global analysis of human population, development level and environment across the north–south axis over the past half century, Appl. Geogr. 31 (2011) 495–507. [CrossRef]

- Natural England, Access to Nature: Regional Targeting Plan – LONDON, (2009). https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20140605113419/http://www.naturalengland.org.uk/Images/London-rtp_tcm6-4496.pdf (accessed January 12, 2024).

- T. Aihara, T. Tayagaki, Y. Nagato, Y. Okano, T. Sugaya, Investigation of the open-circuit voltage in wide-bandgap InGaP-host InP quantum dot intermediate-band solar cells, Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 57 (2018) 04FS04. [CrossRef]

- Delamarre, D. Suchet, N. Cavassilas, Y. Okada, M. Sugiyama, J.-F. Guillemoles, Non-ideal nanostructured intermediate band solar cells with an electronic ratchet, in: SPIE OPTO, SPIE, 2018: p. 5.

- J.F. Geisz, R.M. France, K.L. Schulte, M.A. Steiner, A.G. Norman, H.L. Guthrey, M.R. Young, T. Song, T. Moriarty, Six-junction III–V solar cells with 47.1% conversion efficiency under 143 Suns concentration, Nat. Energy. 5 (2020) 326–335. [CrossRef]

- T. Kita, T. Maeda, Y. Harada, Carrier dynamics of the intermediate state in InAs/GaAs quantum dots coupled in a photonic cavity under two-photon excitation, Phys. Rev. B. 86 (2012) 35301. [CrossRef]

- A. Martí, E. Antolín, C.R. Stanley, C.D. Farmer, N. López, P. Díaz, E. Cánovas, P.G. Linares, A. Luque, Production of Photocurrent due to Intermediate-to-Conduction-Band Transitions: A Demonstration of a Key Operating Principle of the Intermediate-Band Solar Cell, Phys. Rev. Lett. 97 (2006) 247701. [CrossRef]

- Y. Okada, N.J. Ekins-Daukes, T. Kita, R. Tamaki, M. Yoshida, A. Pusch, O. Hess, C.C. Phillips, D.J. Farrell, K. Yoshida, N. Ahsan, Y. Shoji, T. Sogabe, J.-F. Guillemoles, Intermediate band solar cells: Recent progress and future directions, Appl. Phys. Rev. 2 (2015) 21302. [CrossRef]

- Y. Okada, T. Morioka, K. Yoshida, R. Oshima, Y. Shoji, T. Inoue, T. Kita, Increase in photocurrent by optical transitions via intermediate quantum states in direct-doped InAs/GaNAs strain-compensated quantum dot solar cell, J. Appl. Phys. 109 (2011) 24301. [CrossRef]

- M. Rienäcker, M. Schnabel, E. Warren, A. Merkle, H. Schulte-Huxel, T. Klein, M.F.A.M. van Hest, M.A. Steiner, J.F. Geisz, S. Kajari-Schröder, R. Niepelt, J. Schmidt, R. Brendel, P. Stradins, A. Tamboli, R. Peibst, Mechanically Stacked Dual-Junction and Triple-Junction III-V/Si-IBC Cells with Efficiencies of 31.5% and 35.4%, in: 33rd Eur. Photovolt. Sol. Energy Conf. Exhib., 2017. [CrossRef]

- T. Tanaka, K. Matsuo, K. Saito, Q. Guo, T. Tayagaki, K.M. Yu, W. Walukiewicz, Cl-doping effect in ZnTe(1-x)Ox highly mismatched alloys for intermediate band solar cells, J. Appl. Phys. 125 (2019) 243109. [CrossRef]

- A. Vaquero-Stainer, M. Yoshida, N.P. Hylton, A. Pusch, O. Curtin, M. Frogley, T. Wilson, E. Clarke, K. Kennedy, N.J. Ekins-Daukes, O. Hess, C.C. Phillips, Semiconductor nanostructure quantum ratchet for high efficiency solar cells, Commun. Phys. 1 (2018) 7. [CrossRef]

- M. Yamaguchi, K.-H. Lee, K. Araki, N. Kojima, A review of recent progress in heterogeneous silicon tandem solar cells, J. Phys. D. Appl. Phys. 51 (2018) 133002. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

The roof area available for solar panels was found by assuming the dwelling had a 30° inclined roof, with panels on one half of this. A further 20% of this was assumed to be unsuitable for solar panel installation.

Figure 1.

The roof area available for solar panels was found by assuming the dwelling had a 30° inclined roof, with panels on one half of this. A further 20% of this was assumed to be unsuitable for solar panel installation.

Figure 2.

A schematic of the geometry involved in calculating the obliquity factor. The solar panel is located at a latitude of , and is tilted at an angle to the horizontal, while at an azimuthal orientation to the meridian. The normal to the surface of the panel is denoted , while the incident sunlight comes in along the vector .

Figure 2.

A schematic of the geometry involved in calculating the obliquity factor. The solar panel is located at a latitude of , and is tilted at an angle to the horizontal, while at an azimuthal orientation to the meridian. The normal to the surface of the panel is denoted , while the incident sunlight comes in along the vector .

Figure 3.

a) Changing the angle at which the roof of a house is inclined to the horizontal affects the amount of sunlight any solar panels are able to collect due to the cross-sectional area of the roof changing as seen by incident sunlight. When this angle of incline, , is equal to the latitude, , the sunlight is normally incident, and the insolation is maximised. This assumes no azimuthal offset – any such offset will mean the insolation received will be maximised for an angle . (b) While the angle of a roof to the horizontal does affect the amount of sunlight that can be collected, it does not influence the necessary spacing between rows, as the panels are generally laid flat on the roof in a single row – any shadows cast (indicated by the shaded area in this diagram) have no effect on the performance of the array. (c) In the case of a solar farm the latitude, , and the angle to the horizontal, , both influence the distance required between successive rows of solar panels. In this situation, the azimuthal angle, , can be set to zero during construction. Here we set in order to maximise the insolation received by each panel, thus minimising the amount of solar panel material needed.

Figure 3.

a) Changing the angle at which the roof of a house is inclined to the horizontal affects the amount of sunlight any solar panels are able to collect due to the cross-sectional area of the roof changing as seen by incident sunlight. When this angle of incline, , is equal to the latitude, , the sunlight is normally incident, and the insolation is maximised. This assumes no azimuthal offset – any such offset will mean the insolation received will be maximised for an angle . (b) While the angle of a roof to the horizontal does affect the amount of sunlight that can be collected, it does not influence the necessary spacing between rows, as the panels are generally laid flat on the roof in a single row – any shadows cast (indicated by the shaded area in this diagram) have no effect on the performance of the array. (c) In the case of a solar farm the latitude, , and the angle to the horizontal, , both influence the distance required between successive rows of solar panels. In this situation, the azimuthal angle, , can be set to zero during construction. Here we set in order to maximise the insolation received by each panel, thus minimising the amount of solar panel material needed.

Figure 4.

The minimum required PCE (mPCE) as a function of the fractional contribution to the UK’s total energy needs (Contribution). Data are for the average home in London, as calculated using a weighted mean consumption per unit area of roof for the various types of dwelling. These values assume that no energy that is generated is wasted. (a) mPCE as a function of both roof incline, , and Contribution. (b) A cross-section at the minimum, for an angle of , clearly showing the mPCE as a function of Contribution.

Figure 4.

The minimum required PCE (mPCE) as a function of the fractional contribution to the UK’s total energy needs (Contribution). Data are for the average home in London, as calculated using a weighted mean consumption per unit area of roof for the various types of dwelling. These values assume that no energy that is generated is wasted. (a) mPCE as a function of both roof incline, , and Contribution. (b) A cross-section at the minimum, for an angle of , clearly showing the mPCE as a function of Contribution.

Figure 5.

The area of flat land that would need to be dedicated to solar panels of 23.8% power conversion efficiency as a function of the Contribution – the fraction of the UK’s total energy for all sectors that could be generated. This is based on the insolation at the site of an existing solar farm in the UK.

Figure 5.

The area of flat land that would need to be dedicated to solar panels of 23.8% power conversion efficiency as a function of the Contribution – the fraction of the UK’s total energy for all sectors that could be generated. This is based on the insolation at the site of an existing solar farm in the UK.

Table 1.

Calculating the weighted mean total annual energy consumption for homes in London. The energy consumption of each home type has been upscaled to account for all sectors, rather than just domestic (the total value is not upscaled, as the weighted fractional value is simply the sum of the constituent parts).

Table 1.

Calculating the weighted mean total annual energy consumption for homes in London. The energy consumption of each home type has been upscaled to account for all sectors, rather than just domestic (the total value is not upscaled, as the weighted fractional value is simply the sum of the constituent parts).

| House Type |

No. in London (2011) [19] |

Upscaled Energy Consumption (kWh/m2) |

Weighted Fractional Consumption (kWh/m2/yr) |

| Terrace |

756,988 |

2730 |

740 |

| Semi-detached |

617,647 |

3400 |

750 |

| Detached |

205,422 |

2490 |

180 |

| Flat |

1,219,534 |

3570 |

1560 |

| —Total— |

2,799,591 |

— |

3229±1004 |

Table 2.

The

Contribution, calculated separately for each dwelling type, that could be generated by roof-mounted solar panels of the highest efficiency that is available to buy at the time of writing (23.8% [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]); values are given for an optimal 39° roof incline, and we have assumed that all the energy generated can be used without any losses. Uncertainties are propagated using the standard deviation or estimated errors from the sources. Note that the available data does not record the storey height of apartment blocks, so values for the flat are calculated assuming that the total roof area is only divided by two. This is the most optimistic possible estimate of the

Contribution, and is likely to be a considerable overestimate.

Table 2.

The

Contribution, calculated separately for each dwelling type, that could be generated by roof-mounted solar panels of the highest efficiency that is available to buy at the time of writing (23.8% [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]); values are given for an optimal 39° roof incline, and we have assumed that all the energy generated can be used without any losses. Uncertainties are propagated using the standard deviation or estimated errors from the sources. Note that the available data does not record the storey height of apartment blocks, so values for the flat are calculated assuming that the total roof area is only divided by two. This is the most optimistic possible estimate of the

Contribution, and is likely to be a considerable overestimate.

| House Type |

Contribution available from Panels with 23.8% PCE |

| Terrace |

11±2 % |

| Semi-detached |

9±2 % |

| Detached |

12±2 % |

| Bungalow |

14±3 % |

| Flat |

9±4 % |

| Average Home |

9±3 % |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).