Submitted:

02 January 2024

Posted:

18 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

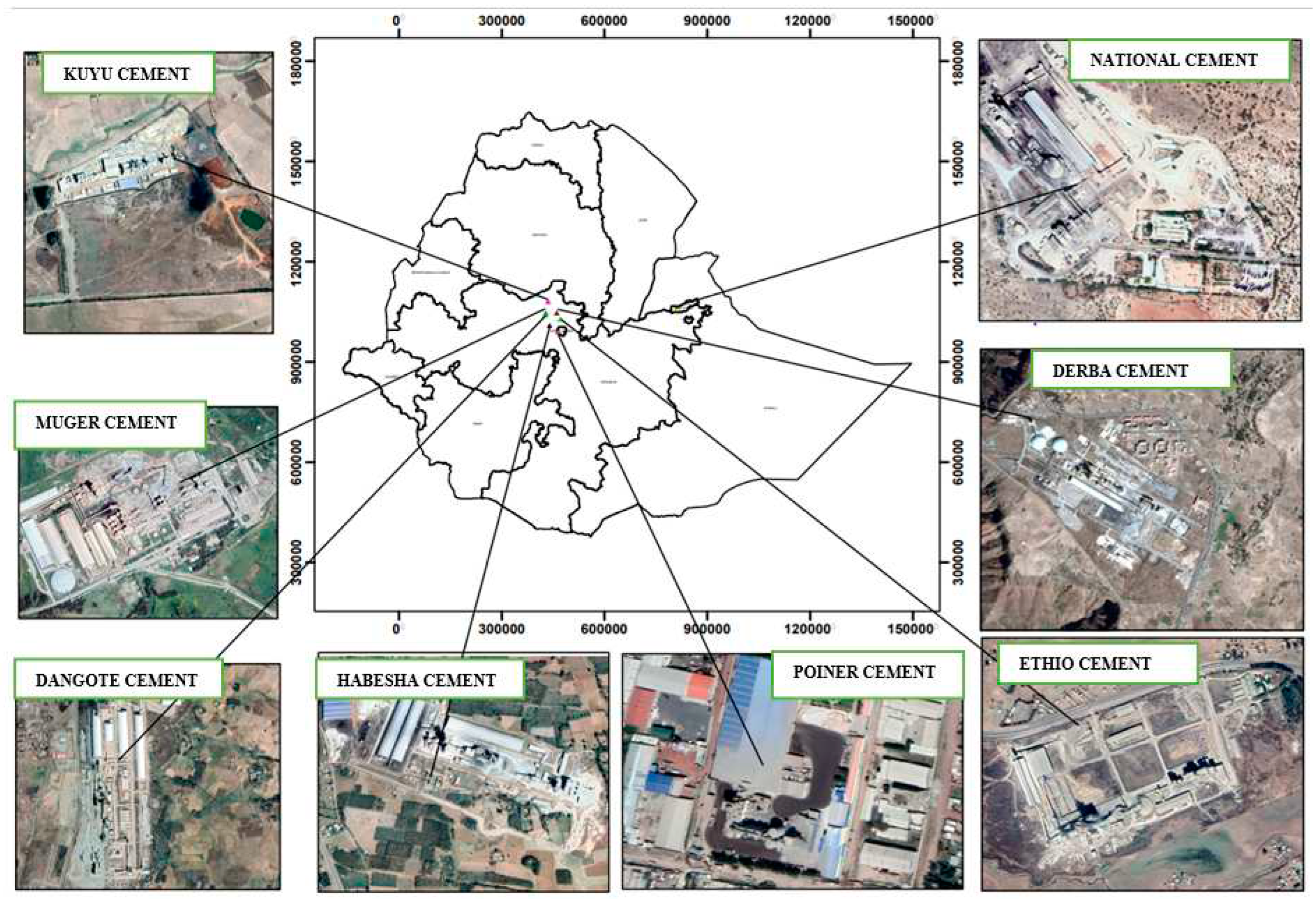

2.1. Description of the study area

2.2. Data collection

2.2.1. Ambient air quality data

2.2.2. Clinical data

2.3. Analysis methods

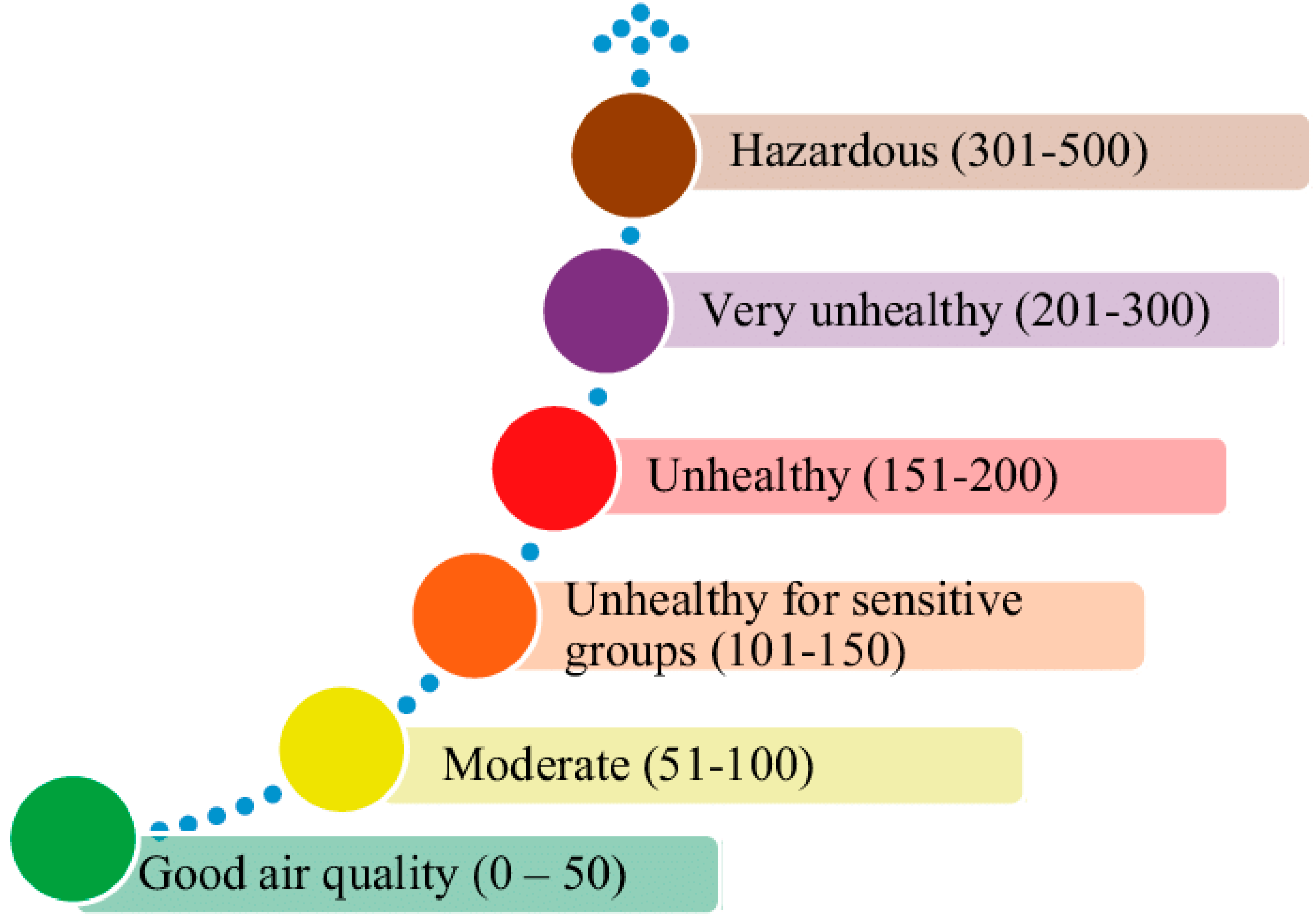

2.3.1. Pollutant Air Quality Index (AQI)

2.3.2. Relationship between exposure to emission and health outcome

2.4. Statistical analysis

3. Results and discussion

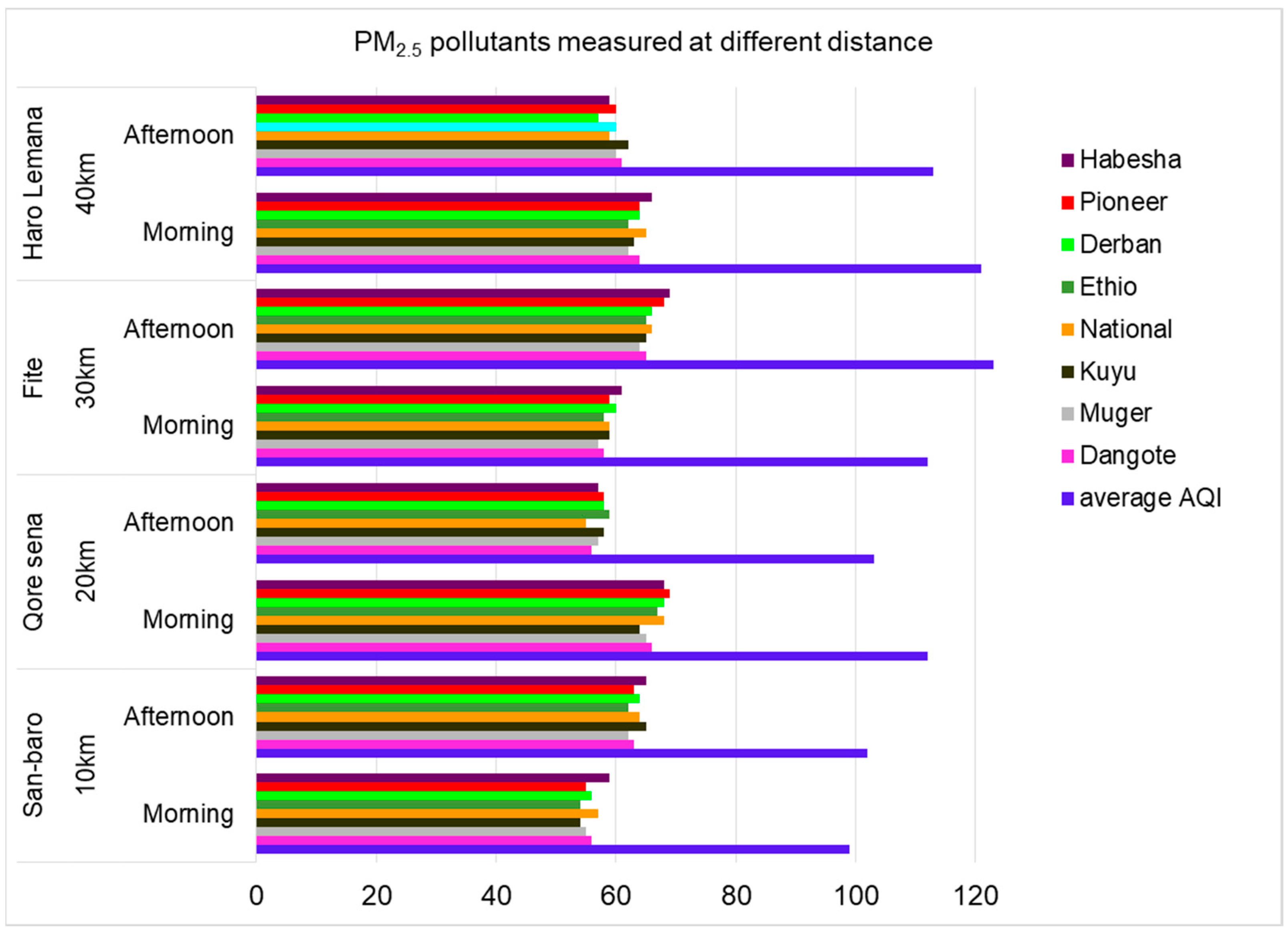

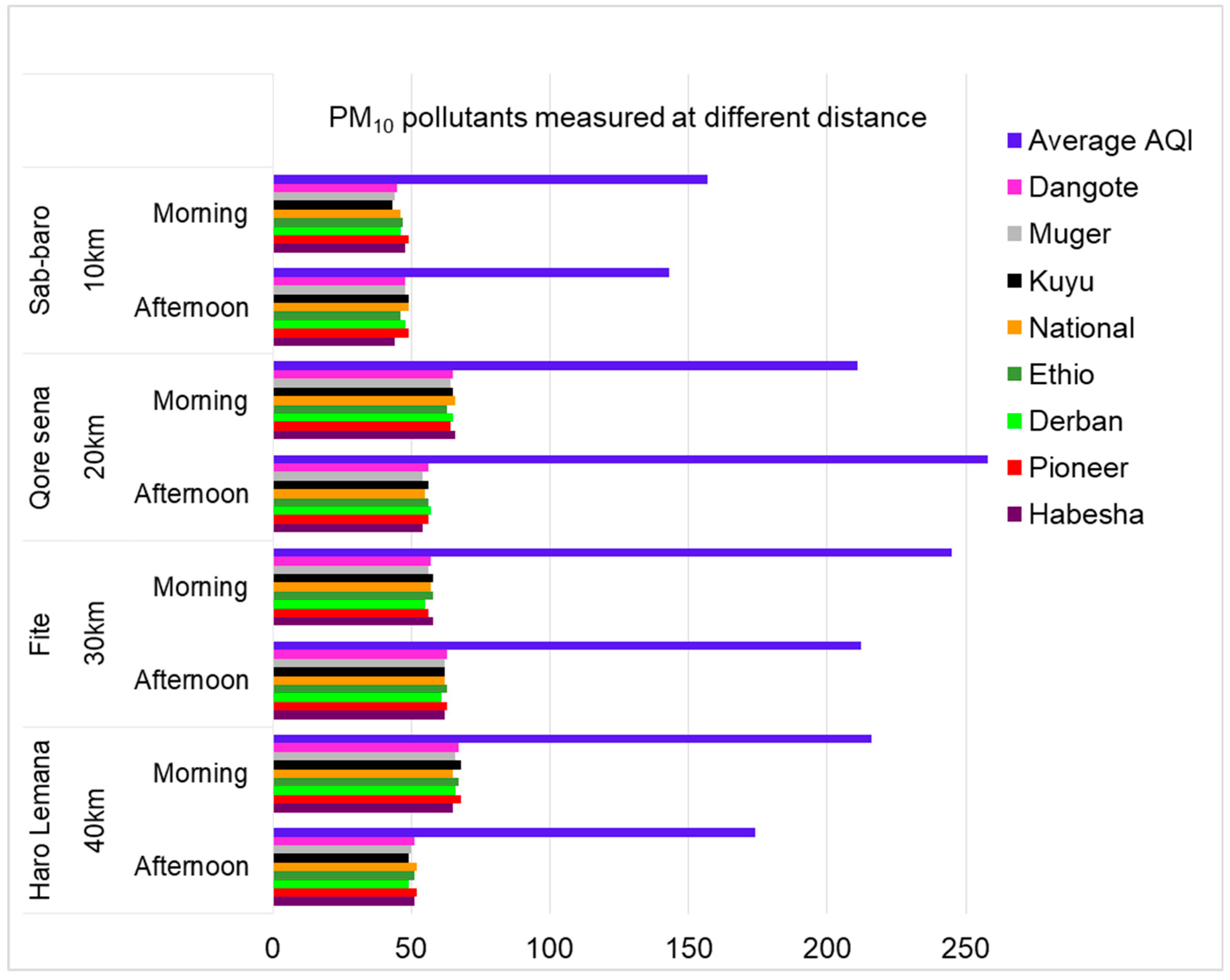

3.1. The PM2.5 and PM10 concentration

3.2. Gaseous concentration

3.3. Emissions of pollutants

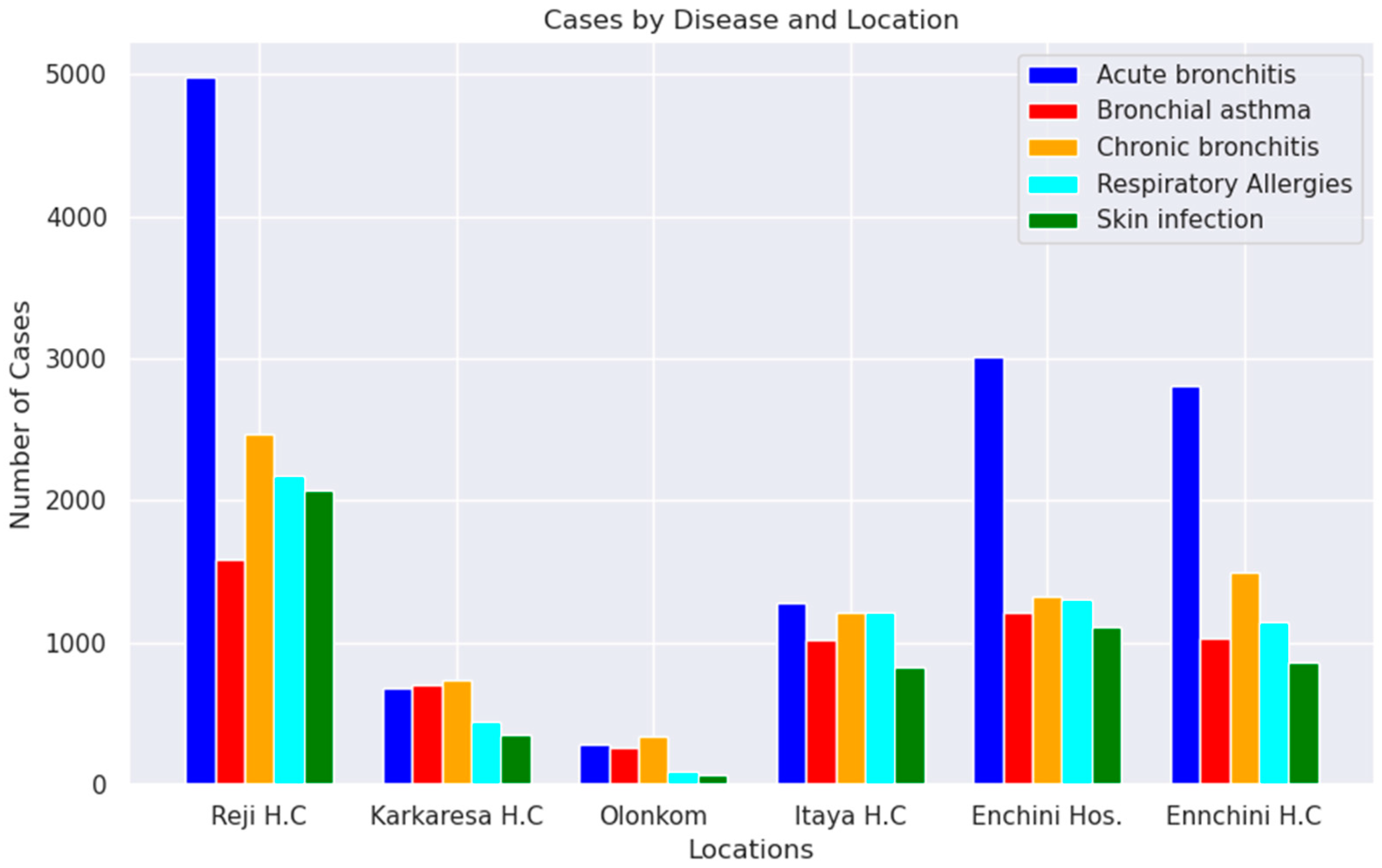

3.4. Health effects

| Types of disease | Age groups | Reji H.C | Itaya H.C | Enchini H.C | Olonkom H.C | Karkaresa H.C | Enchini P. Hospital |

| Bronchial asthma | 0 to 5 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| 6 to 24 | 38 | 18 | 27 | 7 | 12 | 30 | |

| 25 to 60 | 274 | 98 | 155 | 43 | 73 | 134 | |

| > 61 | 10 | 5 | 11 | 1 | 2 | 7 | |

| Total | 326 | 122 | 195 | 51 | 87 | 174 | |

| Chronic bronchitis | 0 to 5 | 5 | 2 | 7 | 3 | 5 | |

| 6 to 24 | 254 | 189 | 287 | 58 | 125 | 198 | |

| 25 to 60 | 312 | 165 | 380 | 69 | 113 | 270 | |

| > 61 | 9 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 8 | |

| Total | 580 | 363 | 681 | 132 | 245 | 481 | |

| Skin infection | 0 to 5 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 | |

| 6 to 24 | 176 | 79 | 178 | 23 | 55 | 144 | |

| 25 to 60 | 187 | 89 | 201 | 19 | 67 | 187 | |

| > 61 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 4 | |

| Total | 369 | 174 | 386 | 45 | 124 | 341 | |

| Acute bronchitis | 0 to 5 | 5 | 3 | 9 | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| 6 to 24 | 550 | 325 | 652 | 121 | 178 | 598 | |

| 25 to60 | 357 | 145 | 454 | 65 | 103 | 389 | |

| > 61 | 20 | 15 | 18 | 5 | 10 | 15 | |

| Total | 932 | 488 | 1133 | 193 | 295 | 1008 | |

| Respiratory allergies | 0 to 5 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 4 | |

| 6 to 24 | 116 | 87 | 123 | 40 | 67 | 128 | |

| 25 to 60 | 198 | 109 | 204 | 54 | 97 | 189 | |

| > 61 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 5 | |

| Total | 321 | 198 | 331 | 99 | 169 | 326 |

3.5. Exposure differences between cases and controls

| Name of Health centre | Exposed | Unexposed | Total sample | Risk | Odds | RR | OR |

| Reji Health centre | 2528 | 2240 | 4768 | 0.53 | 1.13 | 2.12 | 3.23 |

| Enchini Health centre | 2726 | 2042 | 4768 | 0.57 | 1.33 | 2.28 | 3.8 |

| Olonkomii Health centre | 520 | 4248 | 4768 | 0.1 | 0.12 | 0.4 | 0.34 |

| Enchini P. Hospital | 2330 | 2438 | 4768 | 0.49 | 0.95 | 1.96 | 2.71 |

| Karkaresa Health centre | 920 | 3848 | 4768 | 0.19 | 0.24 | 0.76 | 0.69 |

| Itaya Health centre | 1345 | 3423 | 4768 | 0.28 | 0.39 | 1.12 | 1.11 |

| Control | 1253 | 3570 | 5012 | 0.25 | 0.35 |

4. Conclusion and Recommendations

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dure Mulatu, Lulit Habte, Ji-Whan Ahn, The Cement Industry in Ethiopia, J. Energy Eng. 27 (n.d.) 68–73. [CrossRef]

- Julius Mwaiselage, Magne Bråtveit, Bente E Moen, Yohana Mashalla, Respiratory symptoms and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among cement factory workers, Scand J Work Env. Health. 4 (2005) 316–23. [CrossRef]

- Z.K. Zeleke, B.E. Moen, M. Bråtveit, Cement dust exposure and acute lung function: A cross shift study, BMC Pulm. Med. 10 (2010) 19. [CrossRef]

- E. Worrell, L. Price, N. Martin, C. Hendriks, L.O. Meida, C ARBON D IOXIDE E MISSIONS FROM THE G LOBAL C EMENT I NDUSTRY, Annu. Rev. Energy Environ. 26 (2001) 303–329. [CrossRef]

- E. Nkhama, M. Ndhlovu, J. Dvonch, M. Lynam, G. Mentz, S. Siziya, K. Voyi, Effects of Airborne Particulate Matter on Respiratory Health in a Community near a Cement Factory in Chilanga, Zambia: Results from a Panel Study, Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 14 (2017) 1351. [CrossRef]

- S.A. Abdul-Wahab, Impact of fugitive dust emissions from cement plants on nearby communities, Ecol. Model. 195 (2006) 338–348. [CrossRef]

- S. Aydin, S. Aydin, G. Croteau, Í. Sahin, C. Citil, Ghrelin, Nitrite and Paraoxonase/Arylesterase Concentrations in Cement Plant Workers, J. Med. Biochem. 29 (2010) 78–83. [CrossRef]

- Z.K. Zeleke, B.E. Moen, M. Bråtveit, Lung function reduction and chronic respiratory symptoms among workers in the cement industry: a follow up study, BMC Pulm. Med. 11 (2011) 50. [CrossRef]

- S. Peters, Y. Thomassen, E. Fechter-Rink, H. Kromhout, Personal exposure to inhalable cement dust among construction workers, J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 151 (2009) 012054. [CrossRef]

- C. Ciobanu, I.A. Istrate, P. Tudor, G. Voicu, Dust Emission Monitoring in Cement Plant Mills: A Case Study in Romania, Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 18 (2021) 9096. [CrossRef]

- Stewart, R., et al., The Global Burden of Disease: Generating Evidence, Guiding Policy-European Union and European Free Trade Association Regional Edition, nstitute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, Seattle, WA: IHME., 2013. https://www.healthdata.org/research-analysis/library/global-burden-disease-generating-evidence-guiding-policy-european-union.

- S. Mendis, S. Davis, B. Norrving, Organizational Update: The World Health Organization Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases 2014; One More Landmark Step in the Combat Against Stroke and Vascular Disease, Stroke. 46 (2015). [CrossRef]

- A.U. Rauf, A. Mallongi, A. Daud, M. Hatta, W. Al-Madhoun, R. Amiruddin, S.A. Rahman, A. Wahyu, R.D.P. Astuti, Community Health Risk Assessment of Total Suspended Particulates near a Cement Plant in Maros Regency, Indonesia, J. Health Pollut. 11 (2021) 210616. [CrossRef]

- Z. Gizaw, B. Yifred, T. Tadesse, Chronic respiratory symptoms and associated factors among cement factory workers in Dejen town, Amhara regional state, Ethiopia, 2015, Multidiscip. Respir. Med. 11 (2016) 13. [CrossRef]

- V. Etyemezian, M. Tesfaye, A. Yimer, J. Chow, D. Mesfin, T. Nega, G. Nikolich, J. Watson, M. Wondmagegn, Results from a pilot-scale air quality study in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, Atmos. Environ. 39 (2005) 7849–7860. [CrossRef]

- K.T. Beketie, A.T. Angessa, T.T. Zeleke, D.Y. Ayal, Impact of cement factory emission on air quality and human health around Mugher and the surrounding villages, Central Ethiopia, Air Qual. Atmosphere Health. 15 (2022) 347–361. [CrossRef]

- O. Oguntoke, A.E. Awanu, H.J. Annegarn, Impact of cement factory operations on air quality and human health in Ewekoro Local Government Area, South-Western Nigeria, Int. J. Environ. Stud. 69 (2012) 934–945. [CrossRef]

- A.T. Teologo, E.P. Dadios, R.G. Baldovino, R.Q. Neyra, I.M. Javel, Air Quality Index (AQI) Classification using CO and NO2 Pollutants: A Fuzzy-based Approach, in: TENCON 2018 - 2018 IEEE Reg. 10 Conf., IEEE, Jeju, Korea (South), 2018: pp. 0194–0198. [CrossRef]

- WHO, WHO Ambient Air quality database, (2023). https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/air-pollution/who-air-quality-database.

- D. Zmirou, Traffic related air pollution and incidence of childhood asthma: results of the Vesta case-control study, J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 58 (2004) 18–23. [CrossRef]

- C.-Y. Chen, H.-J. Hung, K.-H. Chang, C.Y. Hsu, C.-H. Muo, C.-H. Tsai, T.-N. Wu, Long-term exposure to air pollution and the incidence of Parkinson’s disease: A nested case-control study, PLOS ONE. 12 (2017) e0182834. [CrossRef]

- G.J. Holst, C.B. Pedersen, M. Thygesen, J. Brandt, C. Geels, J.H. Bønløkke, T. Sigsgaard, Air pollution and family related determinants of asthma onset and persistent wheezing in children: nationwide case-control study, BMJ. (2020) m2791. [CrossRef]

- C. Andrade, Understanding Relative Risk, Odds Ratio, and Related Terms: As Simple as It Can Get: (Clinical and Practical Psychopharmacology), J. Clin. Psychiatry. 76 (2015) e857–e861. [CrossRef]

- S. Hennessy, W.B. Bilker, J.A. Berlin, B.L. Strom, Factors Influencing the Optimal Control-to-Case Ratio in Matched Case-Control Studies, Am. J. Epidemiol. 149 (1999) 195–197. [CrossRef]

- G. Rolph, A. Stein, B. Stunder, Real-time Environmental Applications and Display sYstem: READY, Environ. Model. Softw. 95 (2017) 210–228. [CrossRef]

- F.H. Schmidt, C.A. Velds, On the relation between changing meteorological circumstances and the decrease of the sulphur dioxide concentration around Rotterdam, Atmospheric Environ. 1967. 3 (1969) 455–460. [CrossRef]

- A.K. Gorai, F. Tuluri, P.B. Tchounwou, S. Ambinakudige, Influence of local meteorology and NO2 conditions on ground-level ozone concentrations in the eastern part of Texas, USA, Air Qual. Atmosphere Health. 8 (2015) 81–96. [CrossRef]

- B. Zhang, L. Jiao, G. Xu, S. Zhao, X. Tang, Y. Zhou, C. Gong, Influences of wind and precipitation on different-sized particulate matter concentrations (PM2.5, PM10, PM2.5–10), Meteorol. Atmospheric Phys. 130 (2018) 383–392. [CrossRef]

- J. Wang, S. Ogawa, Effects of Meteorological Conditions on PM2.5 Concentrations in Nagasaki, Japan, Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 12 (2015) 9089–9101. [CrossRef]

| Sample room | Pollutant (μg/m3) |

Sampling time |

Name of cement factories | ||||||

| Dangote | Kuyu | National | Ethio | Derba | Pioneer | Habesha | |||

| Mill | PM2.5 | Morning | 617.2 | 599.7 | 611.3 | 613.7 | 611.9 | 613.1 | 598.9 |

| Afternoon | 698.1 | 711.2 | 699.7 | 712.8 | 723.7 | 714.5 | 736.6 | ||

| PM10 | Morning | 607.2 | 707 | 815.3 | 827.7 | 799.5 | 814.2 | 812.4 | |

| Afternoon | 723.9 | 823.4 | 933 | 943.9 | 898.3 | 908.9 | 923 | ||

| Coal crushing | PM2.5 |

Morning | 123.4 | 154.3 | 143.1 | 165.4 | 159.4 | 155.8 | 161.1 |

| Afternoon | 158.2 | 164.4 | 146.8 | 159.3 | 163.2 | 176.1 | 154.2 | ||

| PM10 | Morning | 199.5 | 223.2 | 199.5 | 253.4 | 213.6 | 210.3 | 204.1 | |

| Afternoon | 189.6 | 384.5 | 254.4 | 294.3 | 289.4 | 279.5 | 298.2 | ||

| storage | PM2.5 |

Morning | 216.3 | 209.7 | 199.9 | 213.5 | 212.4 | 216.2 | 213.8 |

| Afternoon | 165.8 | 158.2 | 153.6 | 149.8 | 165.3 | 159.4 | 156.3 | ||

| PM10 | Morning | 654.8 | 764.4 | 724.1 | 764.5 | 732.6 | 765.2 | 777.1 | |

| Afternoon | 553.4 | 673.1 | 633.5 | 633.3 | 654.2 | 687.1 | 686.3 | ||

| loading | PM2.5 |

Morning | 123.5 | 136.4 | 140.2 | 143.3 | 137.2 | 144.3 | 140.2 |

| Afternoon | 143.1 | 143.2 | 132.5 | 138.6 | 138.5 | 129.8 | 140.2 | ||

| PM10 | Morning | 215.2 | 345.4 | 335.0 | 325.6 | 321.1 | 327.3 | 323.2 | |

| Afternoon | 392.8 | 369 | 561 | 467 | 565 | 394 | 569 | ||

| Sample room | Pollutant (mg/m3) | sampling time | Name of cement factories | ||||||

| Dangote | Kuyu | National | Ethio | Derba | Pioneer | Habesha | |||

|

Mill |

CO2 | Morning | 353.2 | 342.4 | 339.8 | 341.2 | 350.3 | 325.6 | 343.1 |

| Afternoon | 543.6 | 564.5 | 567.2 | 569.3 | 568.9 | 588.6 | 570.1 | ||

| N2O | Morning | 1.99 | 2.65 | 2.75 | 2.87 | 2.65 | 2.59 | 2.45 | |

| Afternoon | 3.78 | 4.21 | 4.65 | 4.66 | 3.89 | 3.89 | 4.43 | ||

| SO2 | Morning | 0.31 | 0.282 | 0.282 | 0.2101 | 0.321 | 0.2861 | 0.2651 | |

| Afternoon | 1.02 | 0.99 | 1.11 | 1.03 | 1.04 | 0.98 | 1.05 | ||

| Coal crasher | CO2 | Morning | 245.5 | 267.4 | 238.7 | 255.1 | 242.5 | 247.4 | 243.6 |

| Afternoon | 269.8 | 278.3 | 266.5 | 269.3 | 268.9 | 269.6 | 274.8 | ||

| N2O | Morning | 2.89 | 4.3 | 4.26 | 4.43 | 4.23 | 4.01 | 4.61 | |

| Afternoon | 3.76 | 4.5 | 3.89 | 4.52 | 3.97 | 4.32 | 3.98 | ||

| SO2 | Morning | 0.499 | 0.612 | 0.652 | 0.662 | 0.644 | 0.578 | 0.547 | |

| Afternoon | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.76 | 0.85 | 0.78 | 0.83 | 0.78 | ||

| Storage | CO2 | Morning | 342.7 | 354.1 | 342.4 | 354.3 | 345 | 355.2 | 339.4 |

| Afternoon | 400.01 | 387.8 | 401 | 398.6 | 397.8 | 400 | 398.9 | ||

| N2O | Morning | 1.87 | 2.75 | 2.87 | 2.62 | 2.23 | 2.17 | 2.79 | |

| Afternoon | 1.8 | 2.02 | 2.23 | 2.32 | 2.21 | 2.09 | 2.21 | ||

| SO2 | Morning | 0.32 | 0.213 | 0.311 | 0.269 | 0.269 | 0.199 | 0.267 | |

| Afternoon | 0.161 | 0.163 | 0.152 | 0.149 | 0.161 | 0.498 | 0.155 | ||

| Loading | CO2 | Morning | 361.2 | 365.2 | 363.2 | 354.6 | 360.1 | 362.1 | 363.4 |

| Afternoon | 259.6 | 255.8 | 264 | 259.8 | 258.3 | 263.1 | 262.2 | ||

| N2O | Morning | 7.9 | 8.23 | 8.56 | 7.99 | 8.15 | 7.69 | 8.32 | |

| Afternoon | 6.78 | 6.99 | 7.12 | 6.96 | 7.65 | 6.98 | 7.89 | ||

| SO2 | Morning | 0.71 | 0.712 | 0.558 | 0.692 | 0.597 | 0.655 | 0.697 | |

| Afternoon | 1.22 | 1.213 | 1.187 | 1.1732 | 1.1658 | 1.1231 | 1.1761 | ||

| Sample distance (km) | Pollutant (mg/m3) | Duration | Name of cement factories | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dangote | muger | Kuyu | National | Ethio | Derba | Pioneer | Habesha | ||||

| 10 | C2O | Morning | 399 | 410 | 410 | 411 | 407 | 413 | 419 | 415 | |

| Afternoon | 512 | 513 | 513 | 499 | 512 | 417 | 522 | 509 | |||

| N2O | Morning | 1.143 | 1.234 | 1.234 | 1.198 | 1.312 | 1.288 | 1.197 | 1.213 | ||

| Afternoon | 1.324 | 1.324 | 1.324 | 1.387 | 1.322 | 1.562 | 1.423 | 1.399 | |||

| SO2 | Morning | 0.255 | 0.324 | 0.324 | 0.323 | 0.288 | 0.313 | 0.234 | 0.254 | ||

| Afternoon | 0.432 | 0.419 | 0.419 | 0.455 | 0.394 | 0.432 | 0.423 | 0.435 | |||

| 20 | CO2 | Morning | 437.9 | 445 | 445 | 437.1 | 439 | 463 | 433 | 429 | |

| Afternoon | 299.8 | 326 | 326 | 317 | 309 | 324 | 332 | 324 | |||

| N2O | Morning | 2.23 | 2.22 | 2.22 | 2.21 | 2.32 | 2.26 | 2.34 | 2.36 | ||

| Afternoon | 3.36 | 3.35 | 3.35 | 3.51 | 3.48 | 3.52 | 3.45 | 3.43 | |||

| SO2 | Morning | 0.522 | 0.4982 | 0.4982 | 0.5332 | 0.4897 | 0.5332 | 0.4665 | 0.5753 | ||

| Afternoon | 0.5321 | 0.4887 | 0.4887 | 0.5123 | 0.3987 | 0.5532 | 0.5234 | 0.5023 | |||

| 30 | CO2 | Morning | 283 | 276 | 276 | 269 | 277 | 288 | 279 | 274 | |

| Afternoon | 453 | 435 | 435 | 444.1 | 428 | 447 | 431 | 425 | |||

| N2O | Morning | 1.18 | 1.21 | 1.21 | 1.18 | 1.3 | 1.19 | 1.3 | 1.29 | ||

| Afternoon | 1.29 | 1.32 | 1.32 | 1.28 | 1.29 | 1.28 | 1.28 | 1.22 | |||

| SO2 | Morning | 0.2325 | 0.3015 | 0.3015 | 0.2413 | 0.2432 | 0.2421 | 0.2635 | 0.2432 | ||

| Afternoon | 0.2654 | 0.2543 | 0.2543 | 0.2341 | 0.2124 | 0.2543 | 0.2534 | 0.2543 | |||

| 40 | CO2 | Morning | 255 | 288 | 288 | 268 | 266 | 255 | 264 | 267 | |

| Afternoon | 266 | 278 | 278 | 276 | 272 | 282 | 278 | 270 | |||

| N2O | Morning | 2.01 | 2.21 | 2.21 | 1.89 | 2.02 | 2.34 | 2.25 | 2.02 | ||

| Afternoon | 2.765 | 2.965 | 2.965 | 2.786 | 2.698 | 3.01 | 2.772 | 2.973 | |||

| SO2 | Morning | 0.37 | 0.42 | 0.42 | 0.37 | 0.35 | 0.29 | 0.38 | 0.39 | ||

| Afternoon | 0.54 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.53 | 0.54 | 0.49 | 0.58 | 0.56 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).